Abstract

Delay discounting (DD) is the preference for smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards. Research shows episodic future thinking (EFT), or mentally simulating future experiences, reframes the choice between small immediate and larger delayed rewards, and can reduce DD. Only general EFT has been studied, whereby people reframe decisions in terms of non-goal related future events. Since future thinking is often goal-oriented and leads to greater activation of brain regions involved in prospection, goal-oriented EFT may be associated with greater reductions in DD than general goal-unrelated EFT. The present study (n = 104, Mage = 22.25, SD = 3.42; 50% Female) used a between-subjects 2×2 factorial design with type of episodic thinking (Goal, General) and temporal perspective (Episodic future versus recent thinking; EFT vs ERT) as between factors. Results showed a significant reduction in DD for EFT groups (p < 0.001, Cohen’s d effect size = 0.89), and goal-EFT was more effective than general-EFT on reducing DD (p = 0.03, d = 0.64).

Keywords: episodic future thinking, decision-making, delay discounting

1. Introduction

Imagine choosing between a smaller immediately gratifying reward and a larger reward that you will not receive for many months or years. For example, either going out to a fancy but unhealthy meal now or saving for retirement in the future. In making these types of choices, we are biased toward immediate gratification and discount the future. Immediately gratifying rewards often compete with longer-term rewards or goals, which are of substantially greater value than the immediate reward. Thus, it is not surprising that the inability to delay gratification is a hallmark feature of many maladaptive behaviors such as gambling (Madden, Francisco, Brewer, & Stein, 2011), overeating (Epstein, Salvy, Carr, Dearing, & Bickel, 2010), and substance use (Bickel & Marsch, 2001). Despite the difference in value between the immediate and delayed rewards, individuals frequently discount the value of the delayed reward in favor of the immediate reward, a decisional process known as delay discounting (DD) (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Koffarnus, & Gatchalian, 2012).

One way to shift temporal perspective so that people are more likely to choose a larger, but delayed reward, is to engage in episodic future thinking (EFT) (Daniel, Said, Stanton, & Epstein, 2015; Daniel, Stanton, & Epstein, 2013a, 2013b; Lin & Epstein, 2014; Peters & Buchel, 2010). EFT is a skill that allows us to use mental simulation to place ourselves in the future and pre-experience an event (Atance & O'Neill, 2001). It increases personal connection towards the future, and activates brain regions involved in prospective thinking (Atance & O'Neill, 2001; Hershfield, 2011). EFT helps people accomplish functions such as future planning, decision-making, goal-attainment, and maintaining a personal sense of identity (Atance & O'Neill, 2001; D'Argembeau, Lardi, & Van der Linden, 2012). Engaging in EFT during decision making has been shown to reduce DD (Peters & Buchel, 2010) and is thought to improve the valuation (Benoit, Gilbert, & Burgess, 2011) or the cognitive search for the delayed reward (Kurth-Nelson, Bickel, & Redish, 2012).

Peters and Buchel (2010) were the first to demonstrate that EFT reduces DD. In a within-subjects design, brain activation using fMRI was measured during DD trials that contained either individualized EFT tags (experimental trials) or no tags (control trials). Episodic tags for each participant consisted of either positive or neutral future events that matched the time delays of the DD trials and these tags were matched on valence, arousal, and personal relevance (e.g. “birthday john”). Immediately following the DD task, participants rated the frequency of episodic associations of the tag, and how vivid the associations were during scanning. The vividness of episodic imagery and strength of involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus predicted the effects of EFT on reducing DD (Peters & Buchel, 2010).

Research has shown EFT effectively reduces DD in individuals that are typically high in DD (Daniel et al., 2013a), and that EFT reduces excessive energy intake in obese adults and children as well (Daniel et al., 2015; Daniel et al., 2013b). In these experiments, personalized audio EFT cues that were played during an ad libitum eating task significantly reduced the amount of calories consumed by subjects compared to episodic thinking control conditions. The effect of EFT does not depend on the positive or neutral valence of the cues, but the effect is greater for those with better working memory (Lin & Epstein, 2014).

Benoit et al. (2011) investigated whether imagining spending money in hypothetical future events (e.g. £35 in 180 days at a pub) using EFT reduced DD in comparison to simply estimating what the money could be spent on in the situation. EFT specific to spending money in hypothetical scenarios was associated with a stronger reduction of DD than estimating what items the money could purchase. The effect of EFT on DD was greater for events that produced greater emotional intensity during decision-making. It is possible that imagining real events that someone is looking forward to would be even more powerful than hypothetical events because real events may have greater emotionality. Additionally, imagining future events related to financial goals may increase the ability to delay gratification toward the future than imagining hypothetical spending.

There are individual differences in the extent to which people consider the future consequences of their actions. Some people are more future-oriented while others are more present-focused. People who are more sensitive to immediate consequences may benefit the most from using EFT to delay gratification to the future. Benoit et al. (2011) found that for participants who had higher immediate-biases, the effect of EFT specific to future spending had the greatest impact. In order to understand how to best implement EFT it will be important to continue to investigate whether the tendency to focus on the present or future affects the ability of EFT to reduce DD.

EFT cues in these studies have all been general future events, and not tied to personalized financial goals. However, research suggests that future thinking is often geared towards future goals (D'Argembeau et al., 2010; Smallwood et al., 2011). Furthermore, future thinking regarding personal goals leads to greater activation of brain regions involved in prospection (D'Argembeau et al., 2010). This suggests that, during a financial decision making task, imagining future events that are oriented to future financial goals may be more effective in reducing DD of future monetary rewards then more general future thoughts, such as thinking about an upcoming party. Improving the ability of EFT to reduce DD has important implications in the development of interventions for a variety of behaviors that are compromised by the inability to delay gratification. The present study was designed to investigate whether EFT specifically related to future financial goals and spending was more effective than general non-goal EFT in reducing monetary DD in comparison to episodic recent thinking (ERT) control groups.

2. Methods

2. 1 Participants

Participants (n = 104) were recruited through an Introductory of Psychology subject pool, flyers posted around the University at Buffalo campus, and an existing database maintained by the Division of Behavioral Medicine. Forty-five percent of the participants were minority, fifty percent were female, and the average age was 22.25 (SD = 3.42). All participants graduated high school with eighty-eight percent having completed at least one year of college education. Interested subjects completed an eligibility survey on Survey Monkey prior to scheduling an appointment, to ensure they were 19–35 year old non-smokers with and had no learning disability or psychopathology that would limit adherence to the protocol (e.g. ADHD, depression, substance use other than marijuana or alcohol use). Participants were told they were participating in a study that sought to understand factors that influence financial decision-making, and were compensated with either course credit or mailed a check for $15. The Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board of the State University of New York at Buffalo approved this protocol.

2. 2 Experimental Design and Procedures

Each person was randomized to one of four conditions in a 2 × 2 factorial design, with EFT/ERT and General/Goal as the between group variables. ERT is a good control as it has the participant engage in a similar task that involves generation of recent, rather than future, cues. Eligible participants were scheduled for one 45-minute visit to the laboratory. A pre-session survey measuring participants’ demographics (e.g. age, race) and measures of time orientation were emailed via Survey Monkey to the participant and were completed prior to their appointment. Upon arrival to the Division of Behavioral Medicine, participants were escorted to a private interview room where they were given a brief overview of the study and consented. During the experimental session participants created episodic cues and engaged in EFT or control ERT during a delay-discounting task. Upon completion of the study, participants were given a debriefing form. No deception is used in this research protocol.

2.2.1 Episodic cue generation

One of the four variations of the episodic thinking task was administered to participants depending on their group assignment (i.e. EFT-goal, EFT-general, ERT-goal, or ERT-general). Both of the EFT groups completed trials in which they listed and described positive events that could happen in 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months and 2 years. The creation of the individualized episodic cues began with thinking of a positive future event that took the form of a short sentence. Only positive events were used because they are shown to be more vivid than negative events (Peters & Buchel, 2010). Participants in the EFT-goal group listed future events that they were looking forward to that were related to their financial goals and planning (e.g. “In 2 weeks I am purchasing a new computer”). Participants in the EFT-general group listed future events they were looking forward to in general (e.g. “In 2 weeks I am going home for the weekend”). Thus, the only difference between the two future thinking groups was the inclusion or exclusion of the associated financial goals concerning future events. The timing of the future events coincided with the seven time-delays of the delay-discounting task. Participants rated the salience (importance), valence (enjoyment), arousal (exciting), and vividness of each event on scales from 1-not at all to 5-very much. If events were low in vividness (less than 3), or negative in nature (e.g. “In one day I am taking an exam”) researchers asked if there was a more vivid or positive event that could be used for the time period. Since reductions in rate of discounting occur at more vivid episodic imagery (Peters & Buchel, 2010), events with the highest ratings for vividness were used in the generation of all episodic cues.

Both of the ERT groups were instructed to describe positive events that they enjoyed within the last 84 hours (e.g., 12 hours ago, 24 hours ago, 36 hours ago etc.). The participants in the ERT-goal group were asked to list recent positive events related to their spending or finances, and those in the ERT - general group were asked to list recent positive events. Both groups created a one sentence cue that described their event (e.g. “12 hours ago I purchased a dress that I have wanted”, “12 hours ago I made breakfast at home”). The events were rated for salience, valence, arousal, and vividness (1-not at all to 5-very much) and events with the highest rating were used to generate episodic cues.

For all conditions, the episodic component of the task occurred when the participants were asked to describe in detail what they were imagining about each event. Participants elaborated on where they were, how they were feeling, whom they were with, and what they were doing during the event. These details were combined with the event description to create seven distinct episodic cues, each roughly a paragraph long. These seven personalized episodic cues were then printed. Before each of the seven time delays of the DD task, the corresponding cue was put directly in front of participants for them to read out loud. As a manipulation check, after completing each of the seven time delays of DD, participants rated each event on how often it evoked episodic associations when mentioned (1- never to 5- always) and how vivid these associations were (1- not vivid at all to 5- highly vivid).

2.2.2. Delay discounting task

In the DD task, participants made choices between immediate and delayed hypothetical monetary rewards across seven time delays. The amount of time required to wait for the immediate reward remained constant while the amount of time required to wait for the delayed reward increased. In each of the seven delays, the immediate amounts were available now while delayed rewards were available across a series of seven time delays; 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months and 2 years in the future. The value of the delayed reward remained fixed at $100 while the value of the immediate reward was adjusted in specific dollar increments in either ascending or descending order (Rollins, Dearing, & Epstein, 2010). For each of the seven time delays the immediate reward value cards depicted 30 values ranging from 0.1 to 100% of the delayed reward with which they were compared. Participants were cued to think about their vivid future or recent events during this DD task by reading their cue out loud before each of the seven time delays. The cue was printed in large font and placed in front of the participant for them to read out loud once and then view as they made their choices during the discounting trials. A new cue was used for each time delay; the EFT groups thought of future events that corresponded to the time delay of the DD task while the ERT groups thought about a different recent event during each time delay. The order of discounting trial presentation was counterbalanced (descending versus ascending). The two indifference points produced per delay (i.e., the value of the immediate reward when the participant switched their preference from the immediate to the delayed reward, and the value of the immediate reward when the participant switched preference from the delayed to the immediate reward) were averaged. A researcher administered the task using cards displaying reward choices and recorded participant response after each choice was made. Discounting of rewards in the DD task was determined by calculating area under the curve (AUC) values. AUC is a method of measuring DD by calculating the area under the empirical discounting function (Myerson, Green, Scott Hanson, Holt, & Estle, 2003). Individual AUC scores can range from 0 (highest possible discounting) to 1 (no discounting). As a manipulation check, participants were asked to rate the frequency and vividness of their episodic thoughts after each time delay during the DD task using a Likert scale anchored by 1 = not at all frequent/vivid to 5 = very frequent/vivid. An overall imagery score was calculated by averaging vividness and frequency scores into one variable that assessed the degree to which the participants thought of their episodic events during DD.

2.2.3. Demographics

Participant demographic information was collected (race/ethnicity, family income and educational level) using a standardized questionnaire (Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, 2000).

2.2.4 Time Orientation Measures

The Consideration of Future Consequences Scale (CFCS) assesses the extent to which individuals consider the potential future outcomes of their current behavior and the extent to which they are influenced by the imagined outcomes (Strathman, Gleicher, Boninger, & Edwards, 1994). CFCS was scored for two subscales, Future Orientation and Immediate Consequences. CFCS demonstrates high internal consistency (α=0.80), test-retest reliability after a 5-week interval (r = 0.72, p < 0.001), and convergent validity with a related scale, Ray and Najman’s Deferment of Gratification Scale (r = 0.47, p < 0.01) (Strathman et al., 1994). Individual differences in time period of financial planning were assessed with the question, “In planning your, or your family’s, saving and spending, which of the time periods is more important to you and your partner, if you have one?” Answer choices provided were categorical and ranged from not planning, to planning longer than ten years. Financial planning was converted to a continuous variable for analysis using midpoints of the categories (Picone, Sloan, & Taylor, 2004). Subjective probability of living to age 75 was measured by asking “What do you think are the chances you will live to be 75 or more? (where 0 means there is no chance you will live to 75 or more, and 100 means you will definitely live to 75 or more)” (Picone et al., 2004). Higher values indicate greater future orientation. Time orientation measures were included in order to check for group differences and to investigate whether these measures moderated the effect of EFT on reducing DD.

3. Analytical Plan

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to check for baseline differences in continuous variables and chi-square was used to check for differences in dichotomous variables. Regression models were used to assess main effects and interactions of type of episodic thinking and temporal perspective on DD with centered predictors. Variables that predicted outcome were entered as covariates. Separate models were used to study whether time orientation measures (Consideration of future consequences, subjective probability of living to the age of 75 and financial planning orientation) and ratings of arousal, valence, salience and vividness moderated the effect of type of episodic thinking or temporal perspective on DD. Conditional effects (simple slopes) were used to study differences in DD for participants randomized to EFT or ERT who engaged in general versus goal-oriented episodic thoughts. Cohen’s d effect sizes were included, with values d = 0.2 indicative of a small effect size, d = 0.5 indicative of a medium effect size, and d = 0.8 indicative of a large effect size (Cohen, 1988). Five participants had missing time orientation measure data and were excluded from analyses. Data analyses were completed using Preacher & Hayes SAS Process Macro (Hayes, 2013; Hayes, 2014).

To ensure that the general group did not generate episodic cues that included financial goals, we analyzed the 364 events in the general conditions. No financial oriented statements were observed for 47 of the 52 participants in the general conditions. Five participants generated one cue each (1.4% of all cues) that included financial details. In a separate set of analyses, these five participants were excluded from analyses, and the demonstrated effects remained.

4. Results

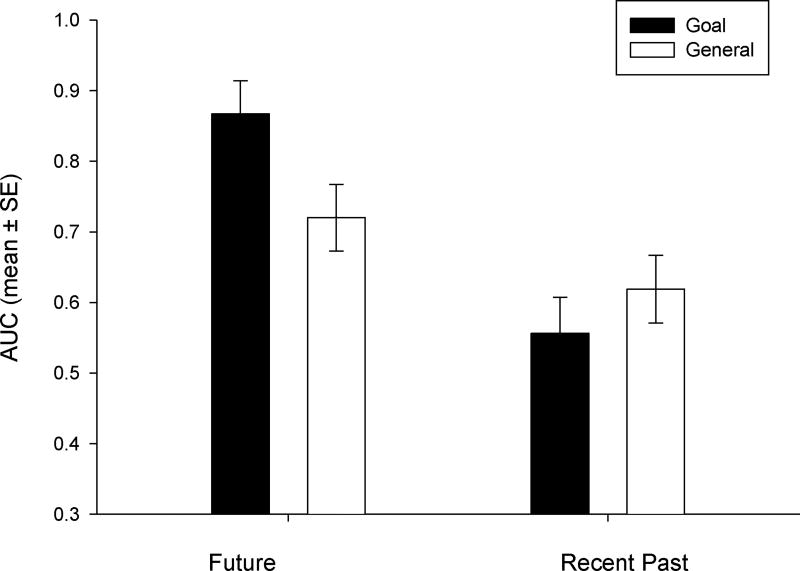

As shown in Table 1, frequency (p = 0.01), vividness (p = 0.001) and salience (p = 0.02) of imagery and the CFCS-Future subscale (p < 0.05) were different between groups. Post-hoc contrasts showed frequency and vividness measures were significantly greater for EFT than ERT (p’s < 0.01), salience was significantly greater for ERT-goal than ERT-general cues (p < 0.001), and CFCS-Future was significantly greater for the ERT-general than the EFT-general (p = 0.03), ERT-goal (p = 0.013), and EFT-goal groups (p = 0.03). Of the three time orientation measures, the only variable that was related to outcome was subjective longevity, which was associated with DD (r(97) = 0.20, p = 0.036). Multiple regression using subjective longevity as a covariate showed a significant interaction between EFT/ERT and type of episodic thinking (Goal, General) of cue (β = −0.21, p = 0.03, Figure 1), with a Cohen’s d effect size of d = 0.45. Temporal perspective significantly predicted DD (β = − 0.20, p < 0.001, d = 0.89), with EFT groups showing less discounting (i.e. higher AUC values) than the ERT groups. Conditional effects showed the EFT-goal group (M = 0.87) showed less future discounting than the EFT-general group (M = 0.72, p = 0.03, d = 0.64). No differences between ERT-goal (M = 0.62) and ERT-general (M = 0.56) on DD were found (p = 0.36). No main effect of goals was observed (β = 0.05, p = 0.33, d = 0.18). Scores on the CFCS, financial planning, and ratings of arousal, valence, salience and vividness did not moderate the effect of time orientation on DD.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics across groups

| EFT | ERT | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goal | General | Goal | General | ||

| n | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 22.1 (.7) | 22.3 (.7) | 21.5 (.7) | 23.1 (.7) | 0.42 |

| n (%) | |||||

| Race | 0.94 | ||||

| Caucasian | 15 (58%) | 13 (50%) | 14 (54%) | 15 (58%) | |

| Non-Caucasian | 11 (42%) | 13 (50%) | 12 (46%) | 11 (42%) | |

| Gender | 0.71 | ||||

| Male | 12 (46%) | 12 (46%) | 14 (54%) | 14 (54%) | |

| Female | 14 (54%) | 14 (54%) | 12 (46%) | 12 (46%) | |

| Measures of Future Orientation (mean ± SD) | |||||

| CFCS_IM | 18.2 (1.0) | 18.9 (1.0) | 19.6 (1.0) | 17.8 (1.0) | 0.60 |

| CFCS_FT | 19.1 (0.5) | 19.0 (0.5) | 18.7 (0.5) | 20.6 (0.5) | 0.048 |

| Financial Planning | 4.2 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.37 |

| Longevity | 77.8 (3.7) | 79.3 (3.7) | 80.6 (4.0) | 77.1 (3.8) | 0.92 |

| Imagery measures (mean ± SD) | |||||

| Frequency | 4.2 (0.1) | 4.1 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1) | 0.01 |

| Vividness | 4.1 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.1) | 0.01 |

| Combined | 4.2 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.1) | 3.6 (0.1) | 0.01 |

| Cue characteristics (mean ± SD) | |||||

| Valence | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.6) | 0.10 |

| Salience | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.7) | 4.1 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.7) | 0.02 |

| Arousal | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.7) | 0.06 |

Figure 1.

Area-under-the-curve (AUC) values (mean ± SE) for discounting of delayed rewards as a function of group assignment.

Using only participants who did not include any financial details in their non-specific cues, results showed that after controlling for subjective longevity, EFT groups had lower rates of discounting than ERT groups (β = − 0.22, p < 0.001, d = 0.89), and there was a significant interaction between type of episodic thinking (ERT, EFT) and thought orientation (Goal, General) (β = − 0.20, p < 0.05, d = 0.42). Conditional effects showed participants randomized to the EFT-goal group had lower discounting rates (i.e. higher AUC values) than those in the EFT-general group (p = 0.046, d = 0.55).

5. Discussion

The results of this study support the hypothesis that EFT can reduce DD (Daniel et al., 2015; Daniel et al., 2013a, 2013b; Peters & Buchel, 2010). Support was also found for the hypothesis that making the episodic thinking cues specific to financial goals amplifies the effect of EFT on reducing monetary DD. This may be particularly relevant for people making financial decisions to buy something now to satisfy the desire for an immediate reward versus saving that money to achieve a desired future financial goal, such as saving for a house, saving for college, or just saving for a higher quality, more expensive version of the commodity that is immediately available.

Typical framing enacts behavior change by shifting attention to the gains or losses in a decision making scenario, thereby promoting risk-averse or risk-seeking decisions (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). Individuals are more reactive to potential losses than to potential gains, often choosing to make riskier choices when facing potential losses (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). In a DD paradigm, respondents choose between two different amounts of money, a smaller reward available immediately or a larger reward available after a time-delay. The typical choice would be to choose the larger later reward because the magnitude of the reward is greater than the immediate reward. However, people often devalue the larger delayed reward in favor of the smaller immediate reward, due to the temptation of its present availability. One way in which EFT enhances behavioral decision-making may be by reframing individual perspective so the future is now. When individuals choose smaller sooner rewards they are focusing on the value of the immediate reward gained (i.e. $40 now), and not the loss associated with rejecting the larger later reward ($100 in 1 month). By reframing the decision to increase personal connectedness to the future using EFT related to future financial goals, the respondent may experience a greater feeling of loss as a result in not choosing the larger later reward. For example, if a person was looking forward to attending the wedding of her best friend from college and needed money to purchase a dress, the choice of an immediate reward, while immediately attractive, would mean a loss of the ability to purchase the dress in the future. In DD, the loss associated with choosing the immediate over the delayed reward may become more cognitively salient when the choice is reframed in the context of a later event that the person is looking forward to. Increasing awareness of future losses promotes loss-averse decisions. Reframing the decision toward future losses may be a mechanism by which EFT results in positive behavior change.

The difference in the effect of goal-specific future thinking and non-goal general future thinking suggests that engaging in future thinking that is aligned to the decision-making task increases activation of brain structures related to prospection in order to counteract the tendency of people to discount the future, and to choose a larger but delayed reward over a smaller, but immediate reward. Recent fMRI data suggest that thinking of goal-related future events activates brain areas associated with prospection more than general events (D'Argembeau et al., 2010).

Overcoming urges for immediate gratification is an important skill that is relevant to many everyday decisions involving self-control. Often financial situations present themselves where an individual most forgo immediate gratification in favor of saving toward a more valuable distal commodity. However, the immediate impulse to buy something that is attractive to you, and would satisfy a perceived immediate desire can interfere with longer-term rewards and goals. People who have difficulty resisting the immediate gratification of buying something now may benefit from imagining themselves in the future having accomplished their goal. EFT permits an individual to fully consider the value of future rewards and the potential consequences of discounting the future for immediate pleasure.

There are two limitations that should be acknowledged to interpret the data. First, the participant sample was highly educated, with average completed education post high school. There is a strong relationship between education level and DD (Reimers, Maylor, Stewart, & Chater, 2009), with persons with lower education showing greater discounting of the future. It is possible that EFT may not benefit persons with lower education levels who have greater discounting of the future. Second, the study was designed to assess specificity of financial goals using a monetary DD task. This is an important first study, as the usual DD task is a monetary discounting task, and it is easy to interpret this data as spending now versus saving now to obtain a greater reward later. Ideally, the effect of goal based EFT would generalize to non-financial goals, such that persons who are obese would benefit more from weight oriented EFT, and addicted individuals would benefit more from EFT focused on cessation of their particular drug of abuse. This study provides a strong basis for testing this generalization to discounting other types of commodities.

Research is needed to bridge the gap between basic laboratory research and applied research, a behavioral decision making version of the bench to bedside analogy that is popular in stimulating biomedical scientists to translate basic science findings into clinical investigations. Research strongly suggests that EFT may be useful for enhancing behavior change (Daniel et al., 2015; Daniel et al., 2013a, 2013b; Lin & Epstein, 2014; Peters & Buchel, 2010) for problems that involve impulsive decision making defined by excessive discounting of the future (Bickel et al., 2012; Bickel & Mueller, 2009). EFT may be a skill that can be learned and translated to many situations involving the choice between a small immediate reward and a larger, delayed reward. EFT may be a useful tool to increase savings behavior by re-framing financial decisions so the future is now. The future self-continuity hypothesis demonstrates stronger feelings of connectedness to ones ‘future self’ are associated with lower temporal discounting, and greater savings accrued (Ersner-Hershfield, Garton, Ballard, Samanez-Larkin, & Knutson, 2009). EFT may be a technique to increase an individual’s personal connectedness to the future, thereby improving delay of gratification and increasing savings as a result. Research is needed to determine how many training sessions are needed to produce sustained effects of EFT in everyday decision making and what impairs EFT for decisions making in naturalistic settings. Answering these questions will allow for a greater understanding of EFT and how it can be used improve decision making in multiple situations.

Highlights.

Engaging in Episodic Future Thinking (EFT) reduces monetary delay discounting (DD)

No studies have manipulated the content of EFT to align with the DD task

We used a 2 × 2 factorial design to compare financial-oriented EFT and general EFT

Two episodic recent thinking groups were used as controls

Financial-oriented EFT was more effective than general EFT on reducing monetary DD

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jonathon Kennedy, Yanling Dong, Jordynn Koroschetz and Alyssa Melber who assisted in recruitment and data entry.

Funding: The research was funded in part by a grant from the Center for Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities, and a University at Buffalo grant 1 R01 HD080292 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded to Dr. Epstein. Study sponsors had no role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychology. 2000;19:586–592. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atance C, O'Neill DK. Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2001;5:533–539. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit RG, Gilbert SJ, Burgess PW. A neural mechanism mediating the impact of episodic prospection on farsighted decisions. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:6771–6779. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.6559-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: emerging evidence. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2012;134:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Mueller ET. Toward the Study of Trans-Disease Processes: A Novel Approach With Special Reference to the Study of Co-morbidity. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2009;5:131–138. doi: 10.1080/15504260902869147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- D'Argembeau A, Lardi C, Van der Linden M. Self-defining future projections: Exploring the identity function of thinking about the future. Memory. 2012;20:110–120. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.647697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Argembeau A, Stawarczyk D, Majerus S, Collette F, Van der Linden M, Feyers D, Salmon E. The neural basis of personal goal processing when envisioning future events. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;22:1701–1713. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TO, Said M, Stanton CM, Epstein LH. Episodic future thinking reduces delay discounting and energy intake in children. Eating Behaviors. 2015;18:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TO, Stanton CM, Epstein LH. The future is now: comparing the effect of episodic future thinking on impulsivity in lean and obese individuals. Appetite. 2013a;71:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TO, Stanton CM, Epstein LH. The future is now: Reducing impulsivity and energy intake using episodic future thinking. Psychological Science. 2013b;24:2339–2342. doi: 10.1177/0956797613488780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Salvy SJ, Carr KA, Dearing KK, Bickel WK. Food reinforcement, delay discounting and obesity. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;100:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersner-Hershfield H, Garton MT, Ballard K, Samanez-Larkin GR, Knutson B. Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow: Individual differences in future self-continuity account for saving. Judgment and Decision Making. 2009;4:280–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York NY, US: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Process for SPSS and SAS [macro] [Retrieved 11/16/2016];2014 from http://afhayes.com/introduction-to-mediation-moderation-and-conditional-process-analysis.html.

- Hershfield HE. Future self-continuity: how conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice. Decision Making over the Life Span. 2011;1235:30–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth-Nelson Z, Bickel W, Redish AD. A theoretical account of cognitive effects in delay discounting. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;35:1052–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Epstein LH. Living in the moment: effects of time perspective and emotional valence of episodic thinking on delay discounting. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;128:12–19. doi: 10.1037/a0035705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Francisco MT, Brewer AT, Stein JS. Delay discounting and gambling. Behavioural Processes. 2011;87:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Scott Hanson J, Holt DD, Estle SJ. Discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards: Processes and traits. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2003;24:619–635. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(03)00005-9. [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Buchel C. Episodic future thinking reduces reward delay discounting through an enhancement of prefrontal-mediotemporal interactions. Neuron. 2010;66:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picone G, Sloan F, Taylor D. Effects of Risk and Time Preference and Expected Longevity on Demand for Medical Tests. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2004;28:39–53. doi: 10.1023/b:risk.0000009435.11390.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers S, Maylor EA, Stewart N, Chater N. Associations between a one-shot delay discounting measure and age, income, education and real-world impulsive behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:973–978. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.026. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins BY, Dearing KK, Epstein LH. Delay discounting moderates the effect of food reinforcement on energy intake among non-obese women. Appetite. 2010;55:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood J, Schooler JW, Turk DJ, Cunningham SJ, Burns P, Macrae CN. Self-reflection and the temporal focus of the wandering mind. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal. 2011;20:1120–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathman A, Gleicher F, Boninger DS, Edwards CS. The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:742–752. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211:453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]