Abstract

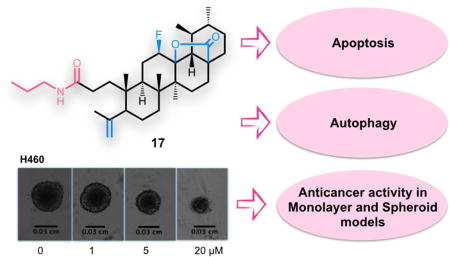

Ursolic acid (UA) is a pentacyclic triterpenoid with recognized anticancer properties. We prepared a series of new A-ring cleaved UA derivatives and evaluated their antiproliferative activity in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines using 2D and 3D culture models. Compound 17, bearing a cleaved A-ring with a secondary amide at C3, was found to be the most active compound, with potency in 2D systems. Importantly, even in 3D systems, the effect was maintained albeit a slight increase in the IC50. The molecular mechanism underlying the anticancer activity was further investigated. Compound 17 induced apoptosis via activation of caspase-8 and caspase-7 and via decrease of Bcl-2. Moreover, induction of autophagy was also detected with increased levels of Beclin-1 and LC3A/B-II and decreased levels of mTOR and p62. DNA synthetic capacity and cell cycle profiles were not affected by the drug, but total RNA synthesis was modestly but significantly decreased. Given its activity and mechanism of action, compound 17 might represent a potential candidate for further cancer research.

Keywords: Triterpenoids, Ursolic acid, Lung cancer, Spheroid, Apoptosis, Autophagy

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is a heterogeneous disease that is divided into two main types, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), with different disease patterns and treatment strategies for each type. The most common type is NSCLC (85%), which includes such subclasses as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinomas [1]. Despite advances in diagnostics and therapeutics, the outcome for patients with lung cancer remains poor [2, 3]. According to GLOBOCAN 2012, the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the most common cause of death by cancer worldwide is lung cancer [4]. A substantial proportion of patients with lung cancer show advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, and 40% of patients with NSCLC have distant metastases [2, 3].

Taking into account the complexity underlying lung cancer, it has been proposed the development of strategies that would target cancer as a complex disease, for example, the use of multifunctional drugs that would modulate the activity of different regulatory networks, affecting as many hallmarks of cancer as possible [5–7].

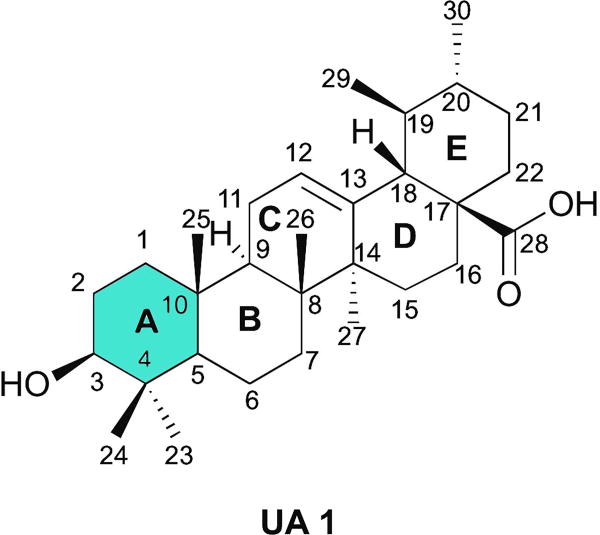

Natural products represent an interesting platform for such strategy, because multitargeted effects have been reported and they have been evolutionarily select to bind to biological macromolecules [8]. However, natural products did not undergo evolutionary selection to serve as human therapeutics and thus need to be optimized to have the desired potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties to become clinically useful drugs. Optimization of the basic scaffold to improve these properties can be accomplished by a semisynthetic approach [8]. Ursolic acid (UA, 1) (Fig. 1), a pentacyclic triterpenoid present in a large variety of medicinal herbs and other plants [9], could be used as one such scaffold. UA (1) antitumor activity has been demonstrated in several cancer cell lines, namely breast, lung, pancreatic, and prostate cancers [10, 11]. The antitumor activity of UA (1) has been attribute to induction of apoptosis [12–14] and differentiation [15, 16]; inhibition of invasion [17], progression [18], and angiogenesis [19, 20]; promotion of chemosensitization [21]; and induction of cell cycle arrest [22, 23]. Given their promising anticancer activity, low toxicity, and commercial availability, several structural modifications of the UA (1) backbone have been explored. The chemical modifications performed so far have focused mostly on the alcohol group at position C3, on the unsaturation on C-ring at position C12(13), and on the carboxylic acid at position C28. Most semisynthetic derivatives obtained have shown improved cytotoxic activity in several cancer cell lines compared with UA (1) [10, 24]. Some UA (1) derivatives have been tested in the A549 lung cancer cell line, e.g., introduction of a piperazine and thiourea moiety at C28 and benzylidine derivatives at C2, among other modifications [25–30]. However, further investigation is needed to develop and synthesize new UA (1) derivatives that could act as agents against lung cancer.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of ursolic acid 1.

In this study, we prepared a series of derivatives with a modified A-ring, using UA (1) as the starting material. The in vitro antitumor activities were tested against NSCLC cell lines, in monolayer and spheroid culture models. The most active compound, compound 17, was selected for further experiments and to determine its mechanism of action in the H460 cell line.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

A series of UA (1) derivatives with a modified A-ring were synthetized as outlined in Schemes 1 and 2, and their structures were fully elucidated. The introduction of nitrogen-containing groups was explored, namely the formation of a lactam, several amides, and a nitrile group. Nitrogen-containing groups offer versatile properties that could improve the biological and pharmacokinetic profile of compounds. Amide bonds, for example, play a major role in the elaboration and composition of biological systems, representing the main chemical bonds that link amino acid building blocks together to form proteins [31–33]. According to one survey, amides are present in 25% of known pharmaceutical [34].

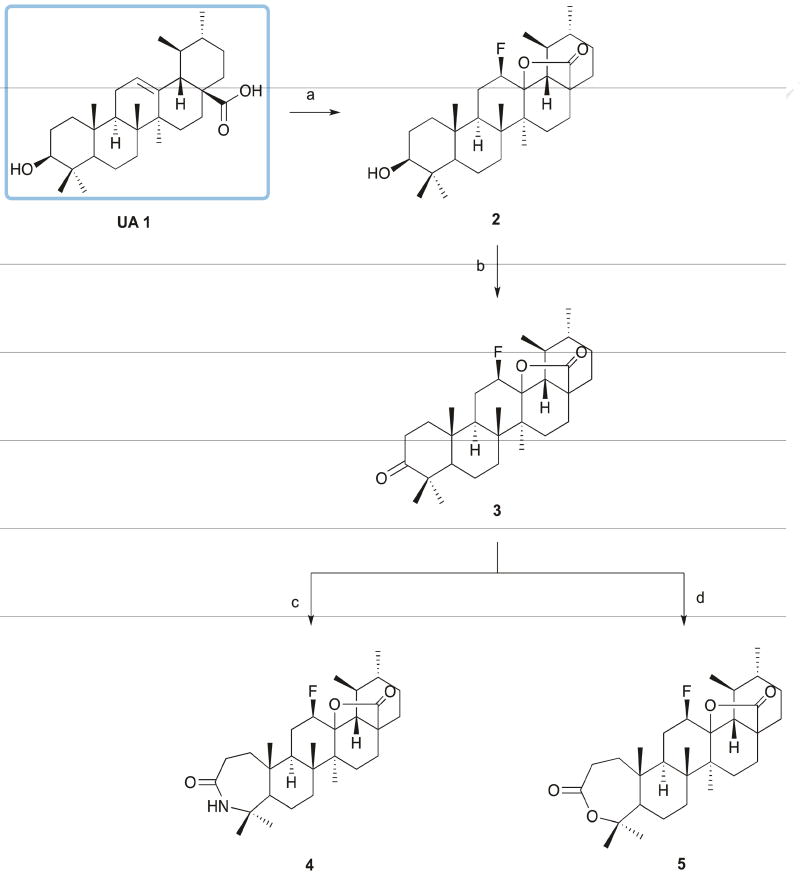

Scheme 1. Reagents and conditions.

a) Selectfluor®, dioxane, nitromethane, 80°C, 24h; b) Jones reagent, acetone, ice; c) i - glacial acetic acid, sulfuric acid, NaN3, 65°C; ii - 30°C, 5h; d) m-CPBA 77%, CHCl3, r.t., 120h.

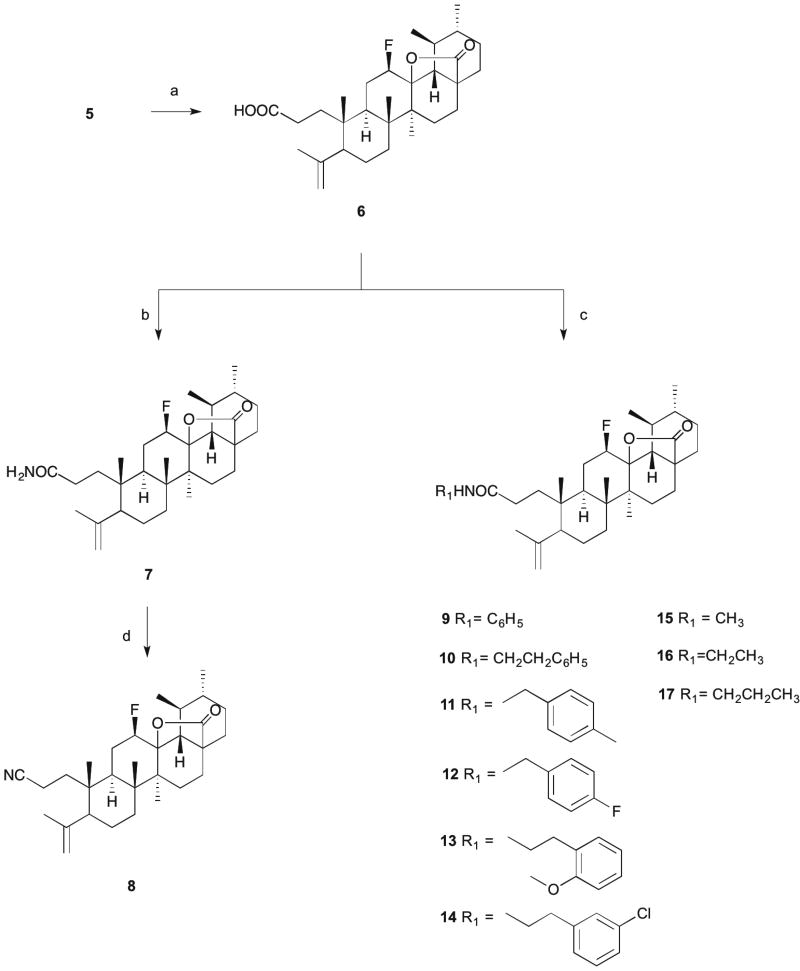

Scheme 2. Reagents and conditions.

a) p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate, CH2Cl2, r.t., 24h; b) i -oxalyl chloride, dry CH2Cl2, r.t., 15h; ii - cold 25% ammonium aq. solution, dry THF, 2h; c) RNH2, dry THF, Et3N, T3P(50 wt. % in THF), ice; d) T3P (50 wt. % in THF), THF/EtOAc, Et3N, 77°C , 5h.

The synthetic route began with the formation of 12 β-fluoro-13,28 β-lactone (2) via reaction of UA (1) with Selectfluor® fluorinating reagent in a mixture of nitromethane and dioxane at 80°C, with yields above 60% [35]. The fluorination reaction was selected as the first step of the synthetic scheme, because some functional groups synthesized can also be fluorinated, resulting in a mixture of fluorinated compounds. The presence of fluorine, a small and highly electronegative atom, in key positions of a biologically active molecule has been shown to improve the metabolic and chemical stability, membrane permeability, and protein-binding affinity of the agent [36, 37]. The introduction of the 12β-fluorolactone was confirmed by the presence in the 1H NMR spectra of a double triplet or double quartet at 4.55–5.00 ppm, with a coupling constant of around 45 Hz, characteristic of the geminal proton for the β-fluorine. In the 13C NMR spectra, we observed a doublet for the signal of C12 (88.50 – 89.50 ppm) and of C13 (91.50–92.00), with coupling constants of 186 and 14 Hz, respectively. This profile of 1H and 13C NMR spectra is characteristic of the β-isomer [35].

After oxidation by Jones reagent, the treatment of 3-oxo-derivative 3 with NaN3 in glacial acetic acid and sulfuric acid afforded lactam 4, while the treatment of compound 3 with m-chloroperbenzoic acid (m-CPBA) in CHCl3 afforded lactone 5, with yields around 60% (Scheme 1). For the formation of N-derivatives, lactone 5 was cleaved using p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate in CH2Cl2 to give 6 (Scheme 2). The cleavage of A-ring with formation of a carboxylic acid and unsaturation at C4(23) position was confirmed by the presence in the 1H NMR spectrum of two singlets for the protons at position 23 at 4.88 and 4.67 ppm. In the 13C NMR spectrum, the carbon of the carboxylic acid was observed at 179.71 ppm, close to the carbonyl carbon signal of the fluorolactone (179.02 ppm). Unsaturation at C4(23) was observed at 146.85 ppm and 114.13 ppm, which was determined as a quaternary carbon (C4) and as a secondary carbon (C23) by 13C and DEPT-135 NMR spectra.

Compound 6 was first treated with oxalyl chloride and then reacted with cold 25% ammonium aqueous solution to generate the primary amide 7. The introduction of the amide function in compound 7 was confirmed in the 1H NMR spectrum by a broad singlet at 5.80 ppm for the proton of the amide function. The carbonyl carbon of the amide group was observed in the 13C NMR spectrum at 176.14 ppm.

The reagent T3P® (propylphosphonic anhydride solution, 50 wt. % in THF) was used to prepare several amide derivatives (9–17) and the nitrile derivative (8) (Scheme 2). T3P is an efficient coupling reagent that has been employed for the conversion of carboxylic acids to aldehydes and amides, amides to nitriles, and formamides to isonitriles, as well as for the synthesis of heterocycles, Weinreb amides, β-lactams, hydroxamic acids, acyl azides, esters, imidazopyridines, and dihydropyrimidinones [38–40]. The free carboxylic acid group of compound 6, in the presence of T3P (50 wt. % in THF) and Et3N (triethylamine) in THF in an ice bath, reacted with several amines to yield the respective amide derivatives (9–17). Compound 8 was obtained by reducing the amide 7 with T3P (50 wt. % in THF) in a mixture of THF/EtOAc and Et3N at 77°C for 5h. In the 1H NMR spectra, we observed a broad singlet or triplet for the proton of the several amides around the chemical shifts of 5.7 and 5.3 ppm. The carbonyl carbon of the amide was observed in the region of 173 ppm in the 13C NMR spectra. The nitrile derivative 8 was confirmed in the 1H NMR spectrum by the disappearance of the proton signal of the NH group and in the 13C NMR spectrum by the disappearance of the carbonyl carbon signal at 173 ppm and appearance of the carbon signal of the nitrile group at 120.39 ppm.

2.2. Biological studies

2.2.1. Evaluation of in vitro antitumor activity

The anti-tumor activities of UA (1) and all the newly synthesized derivatives against NSCLC cells (H460, H322, H460 LKB1+/+) were evaluated using the CellTiter-Blue® assay. A culture medium containing 0.15% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) served as negative control. The cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of each compound, and the IC50 values (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) were determined after 72h of incubation. The values for IC50 are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The inhibitory activities (IC50) of ursolic acid (UA 1) and derivatives 2–17 in the lung cancer cell lines.

| Cell line(a)/IC50

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | H460 | H322 | H460 LKB1+/+ |

| UA 1 | 14.8±0.6 | 15.3±2.8 | 21.1±1.6 |

| 2 | 19.3±2.6 | 14.3±2.7 | 18.7±3.7 |

| 3 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 4 | >25 | >25 | 13.5±0.5 |

| 5 | ND | ND | ND |

| 6 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 7 | 23.0±2.3 | 24.1±2.5 | 21.8±3.2 |

| 8 | >17 | >17 | >17 |

| 9 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 10 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 11 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 12 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 13 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 14 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 15 | 4.5±0.4 | 6.8±1.5 | 6.7±0.5 |

| 16 | 5.3±0.3 | 7.3±1.0 | 7.8±1.1 |

| 17 | 2.6±0.9 | 3.3±0.9 | 4.4±0.6 |

Lung cancer cell lines were treated with various concentrations of test compounds for 72h. The inhibitory activities were determined using CellTiter-Blue®. IC50 was calculated from the results, and data are presented as means ± SD (standard deviation) of three independent experiments.

As shown in Table 1, the introduction of the fluorolactone moiety into the UA (1) backbone, compound 2, was not critical for the cytotoxic activity. Nevertheless, the incorporation of a fluorine atom into the UA (1) structure was designed based on the desirable properties that have been attributed to the fluorine atom in several drug candidates, such as improved pharmacokinetic profile [41].

The ring expansion did not contribute to the biological activity compared with the parent compound. The lactam 4 showed a dramatic increase in the IC50 values in the H460 and H322 cell lines, whereas the formation of lactone 5 led to a less soluble derivative for the biological assays, and so lactone 5 was not further tested.

The cleavage of A-ring with formation of a carboxylic acid function at C3 and an unsaturation at C4(23) 6, in order to obtain the amide derivatives, improved the solubility compared with its antecedent but did not improve cytotoxic activity. The primary amide 7 showed an improved activity compared with 5 and 6 but not compared with the parent compound. The introduction of a secondary amide with an aromatic substituent (9–14), a more bulky group, led to compounds with decreased activity compared with the primary amide and parent compound. However, when a secondary amide with a short alkyl side chain was introduced (15–17), the cytotoxicity was improved compared with the primary amide 7 (×9) and the parent compound (×5). Finally, the reduction of the primary amide to a nitrile function (8) led to a decreased activity.

In brief, the fluorolactone moiety was not critical to the cytotoxic activity of the newly synthetized derivatives, the formation of a seven-membered A-ring decreased the activity, and the cleavage of A-ring did not improved the activity. Analyzing the A-ring cleaved derivatives, we found that the presence of an unsaturation at C4(23) position did not seem to contribute to the cytotoxic activity, whereas the substitution at C3 had a dramatic influence on biological activity. Comparing the amide derivatives, the secondary amide with a more bulky side chain displayed a pronounced decrease in cytotoxic activity, whereas the presence of a secondary amide with a small alkyl side chain led to the most active compounds, with compound 17 being five times more potent than the parent compound in all cell lines.

Monolayer cultures of cells are the most commonly used model to screen for the cytotoxic activity of new drugs. However, this model lacks the three-dimensionality, heterogeneity, dense extracellular matrix, and penetration barriers observed in vivo, and hence the effects observed may overestimate or underestimate the actual effects observed in vivo in solid tumors. The use of three-dimensional (3D) models has been proposed as an attractive approach to overcome some of the limitations of the traditional two-dimensional (2D) systems, because such models mimic more closely the complex cellular heterogeneity, cell/cell interactions, and tumor microenvironment observed in vivo. One example of such a 3D system are spheroids. Spheroids are spontaneously aggregating three-dimensional cultures of tumor cells. Compared with their 2D counterparts, spheroids develop important physiological parameters of heterogeneous tumors, such as tight cell-cell interactions and mechanical tissue properties. In addition, similar to the in vivo environment, tumor spheres are exposed to nutrients, oxygen, pH, growth factors, and anticancer drug gradients, which generate necrotic, hypoxic, quiescent, and proliferative zones from the inner spheroid core to the outer surface [42–48]. The H460 and H322 NSCLC cell lines are able to spontaneously form spheroid aggregates, using plates with an ultra-low attachment surface that has covalently bonded hydrogel that minimizes cell attachment, protein absorption, enzyme activation, and cellular activation.

The antitumor activity of UA (1), fluorolactone derivative 2, and the three most potent synthesized derivatives (15–17) were tested against H460 and H322 cells in a spheroid model using the CellTiter-Glo® assay. A culture medium containing 0.15% DMSO served as negative control. The cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of each compound, and the IC50 values were determined after 96h of incubation. The IC50 values are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The inhibitory activities (IC50) of ursolic acid (UA 1), derivative 2, and the most potent derivatives (15–17) in spheroid model of the H460 and H322 lung cancer cell lines.

| Cell line(a)/ IC50, µM

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | H460 | H322 | ||

|

|

||||

| Monolayer | Spheroid | Monolayer | Spheroid | |

| UA 1 | 14.8±0.6 | 30.8±2.8 | 15.3±2.8 | 18.2±10.5 |

| 2 | 19.3±2.6 | 19.5±10.4 | 14.3±2.7 | ND |

| 15 | 4.5±0.4 | 3.0±1.2 | 6.8±1.5 | 12.1±1.7 |

| 16 | 5.3±0.3 | 5.7±0.3 | 7.3±1.0 | 11.6±7.4 |

| 17 | 2.6±0.9 | 5.5±0.8 | 3.3±0.9 | 10.0±1.2 |

Lung cancer cell lines were treated with various concentrations of test compounds for 72h or 96h for a 2D (monolayer) or 3D model (spheroid), respectively. The inhibitory activities were determined using CellTiter-Blue® or CellTiter-Glo® for the 2D or 3D model, respectively. IC50 was calculated from the results, and data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

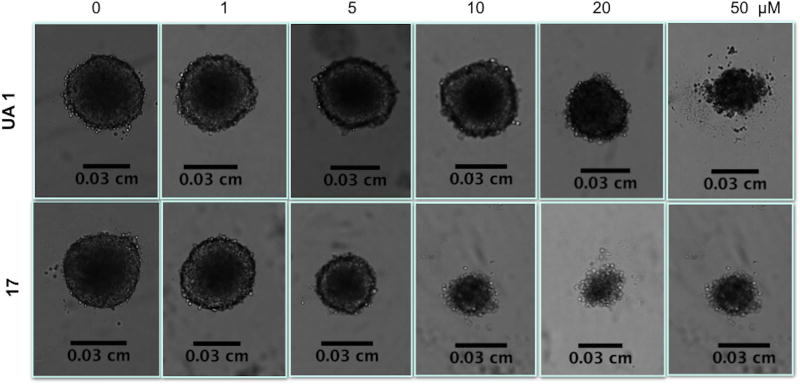

The most active derivatives (15–17) showed cytotoxic activity in the spheroid model, although the IC50 value increased in most cases, with the exception of compound 15, which presented similar values of IC50 in the H460 cell line in both models (Table 2). Interestingly, the H322 cell line seemed to be more resistant than the H460 line in the spheroid model, as IC50 values were higher comparing to monolayer system. In Fig. 2, it is possible to observe effects of UA 1 and 17 in the spheroid model for the H460 cell line at 96h of treatment.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic changes in the H460 spheroid model treated with UA (1) (top panel) and C17 (bottom panel) for 96h. Spheroids were treated with the indicated concentrations of UA derivatives. Images were captured using a bright field phase-contrast microscope.

2.2.2. Effect of compound 17 on cellular DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis

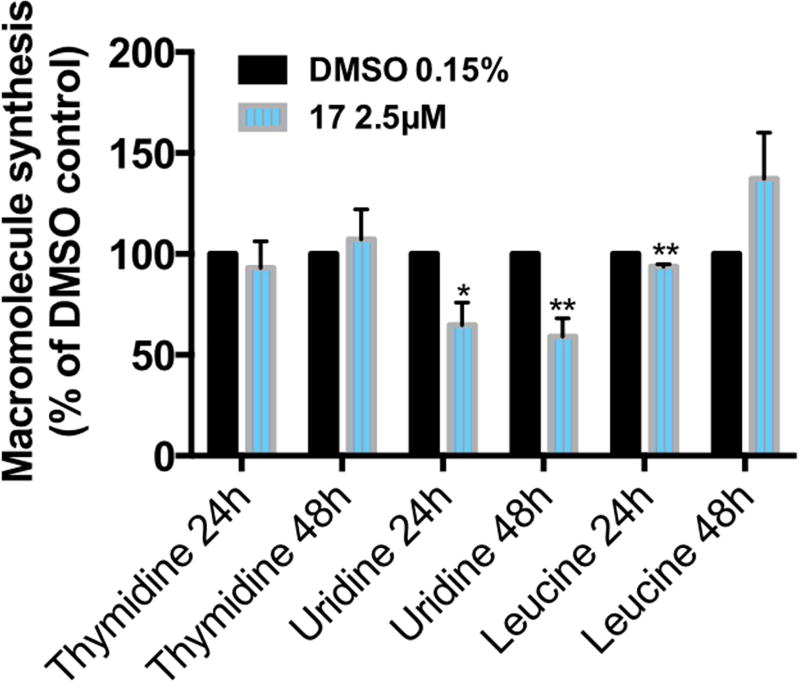

The [3H]thymidine, [3H]uridine, and [3H]leucine incorporation assays allow measurement of the effects of a compound in the DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis rates of cells, respectively (Fig. 3). Although DNA and protein syntheses were not affected by treatment with compound 17, the RNA synthesis was decreased to 65% and 60% at 24h and 48h, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of C17 treatment on the global DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in the H460 cell line. Cells treated with vehicle or compound 17 at the indicated concentrations for 24h and 48h were assessed for macromolecule synthesis. Values represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments. p-Values obtained by comparing vehicle and treatment are presented as *<0.05 and **<0.01.

2.2.3. Annexin V-Cy5/PI flow cytometric assay

Apoptosis is a process of programmed cell death that plays an important role in the development and homeostasis in normal tissues. However, defects in programmed cell death mechanisms are fundamental for tumor pathogenesis, allowing neoplastic cells to survive over an extended lifespan, with accumulation of genetic alterations that deregulate cell proliferation and differentiation [49].

In the earliest stages of apoptosis, the plasma membrane loses its symmetry and the membrane phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS) is translocated from the inner to the outer leaflet of the membrane, exposing PS to the external environment. Annexin V-Cy5 has a high affinity for PS and binds to the exposed apoptotic cell surface PS, thus allowing the quantitative assessment of apoptosis. In the late stages of apoptosis, the membrane loses its integrity and propidium iodide (PI) can enter the cell [50].

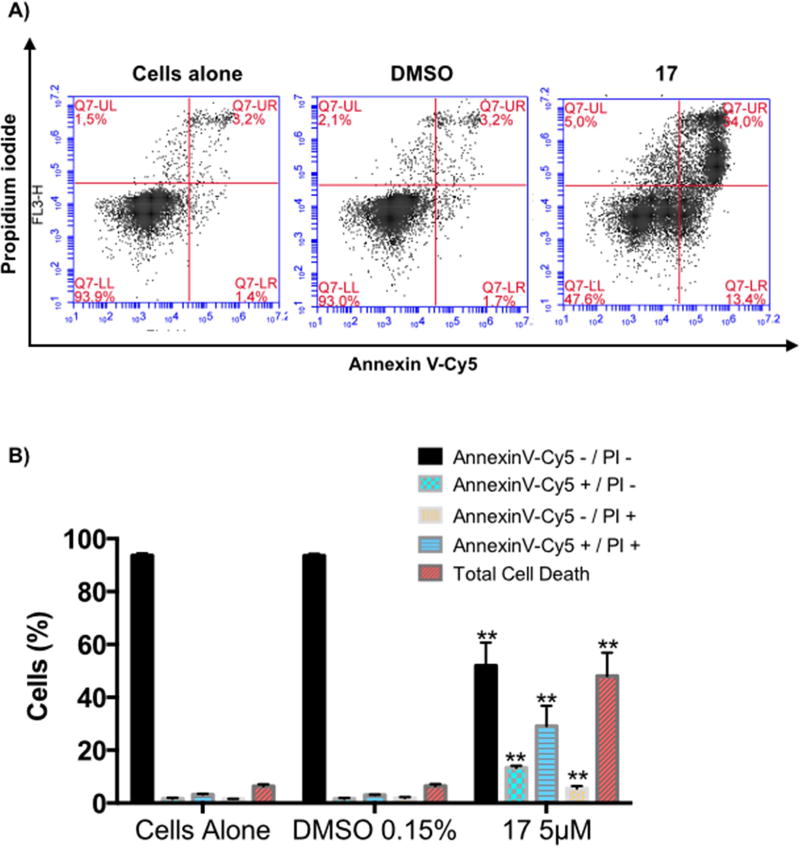

Treatment of H460 cells with compound 17 at 5 µ M for 72h led to an increased number of apoptotic cells, from 4.9% to 42.54% in treated cells (i.e., 13.4% of early apoptotic cells and 29.14% of late apoptotic cells) (Fig. 4). Concomitantly, the percentage of live cells decreased to 94% in the control and to 51.94% in treated cells. These results suggest that compound 17 at 5 µ M induces apoptosis in H460 cells.

Figure 4.

Induction of H460 cell death by C17. Annexin V-Cy5/PI assay of H460 cells untreated, treated with vehicle, or treated with compound 17 at the indicated concentrations for 72h. A) Representative flow cytometric plots for the quantification of apoptosis are shown: the lower left quadrant (annexin V− and PI−) represents non-apoptotic cells, the lower right quadrant (annexin V+ and PI−) represents early apoptotic cells, the upper right quadrant (annexin V+ and PI+) represents the late apoptotic/necrotic cells, and the upper left quadrant (annexin V− and PI+) represents necrotic cells. B) The bar graph depicts the variation of the percentages of live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic cells, necrotic cells, and total cell death. Values represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments. p-Values obtained by comparing vehicle and treatment are presented as *<0.05, **<0.01.

2.2.4. Effect of compound 17 on the levels of apoptosis-related proteins

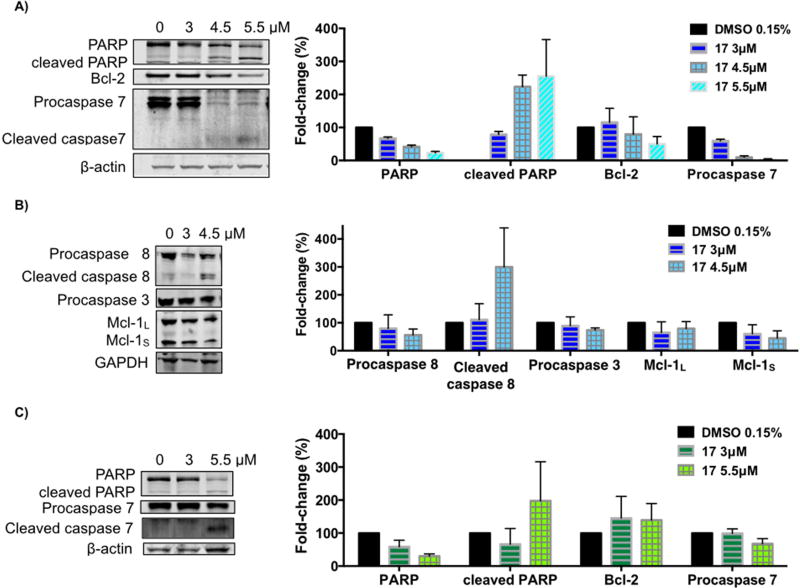

To gain a deeper insight into the mechanism of C17-induced apoptosis in the H460 cell line, we used immunoblot analysis to assess the levels of some apoptosis-related proteins. H460 and H322 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of compound 17 for 24h (Fig. 5). The activation of caspases is one of the fundamental mediators of apoptosis and the proteolytic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP), particularly by caspase-3 and caspase-7, is another characteristic event of apoptosis [51]. As shown in Fig. 5, treatment of H460 cells with compound 17 induced cleavage of full-length PARP as well as cleavage of procaspase-8 and procaspase-7 into their active forms (Fig. 5A and 5B). However, the level of procaspase-3 was decreased by only 29% at the higher concentration of 4.5 µ M (Fig. 5B). Whilst compound 17 did not seem to significantly alter the levels of procaspase-9 (data not shown), the significant increase in the level of activated caspase-8 suggests that compound 17 induces apoptosis mainly through the extrinsic pathway. Increases in the cleaved levels of PARP and procaspase-7 were also observed when the H322 cell line was treated with compound 17 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Effect of compound 17 on the levels of apoptosis-related proteins. H460 cells (A–B) and H322 cells (C) were treated with compound 17 at the indicated concentrations for 24h. The levels of the indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blot. β-Actin or GAPDH was used as loading control. The bar graph depicts the variation of the levels of the protein expression. Values are the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

The levels of Bcl-2 and Mcl-1, two proteins from the Bcl-2 family, were also explored. Bcl-2 protein serves as an anti-apoptotic effector, whereas Mcl-1 can occur in two alternative splicing variants, a longer (Mcl-1L) and a shorter (Mcl-1S) gene product, with the first one acting as an anti-apoptotic effector and the shorter as a pro-apoptotic effector [51, 52]. As depicted in Fig. 5A and B, the treatment of H460 cells with compound 17 caused downregulation of Bcl-2 and both isoforms of Mcl-1 in a concentration-dependent manner.

2.2.5. Effect of compound 17 treatment on autophagy

According to HTA2.0 microarray and RPPA (reverse-phase protein array) results (supplementary information), the autophagy pathway was activated upon treatment of the H460 cells with compound 17 at 24h.

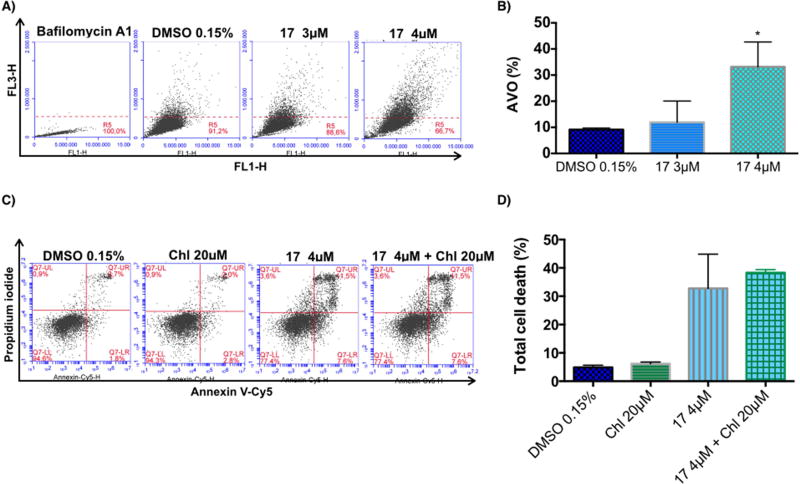

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred as autophagy) is a catabolic process involved in the degradation of the components of a cell through the lysosomal machinery. During autophagy, portions of the cytoplasmic materials and intracellular organelles are sequestered into double-membrane organelles known as autophagosomes, which degrade the sequestered contents by fusion with lysosomes to form autolysosomes [53]. Autophagy is characterized by the formation of acidic vesicular organelles (AVO), which can be detected by staining with acridine orange, a dye that accumulates in acidic organelles [54]. Measurement of this dye by flow cytometry was used to detect AVO formation in H460 cells treated with vehicle (0.15% DMSO) or compound 17 (3 µ M or 4 µ M) for 72h. Bafilomycin A1 was used as a negative control to block acidic vesicular formation. As depicted in Fig. 6A, bafilomycin A1 inhibited the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes (acidic vesicles). Endogenous autophagy level (DMSO treatment) was less than 10% at 72h (Fig. 6A and 6B). Treatment with compound 17 significantly increased the formation of AVO at 4 µ M (Fig 6A and 6B). These data suggest that compound 17 is able to induce autophagy in H460 cells.

Figure 6.

Effect of C17 treatment on induction of autophagy in the H460 cell line and the effect of its inhibition. A) The formation of acidic vascular organelles (AVO) was measured by acridine orange staining and flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometric plots of the percentage of AVO formation (acridine orange staining positive) of three independent experiments are shown. B) The graph bar depicts the variation of the percentage of AVO formation (acridine orange staining) and is plotted as means ± SD of three independent experiments. p-Values obtained by comparing vehicle and treatment are presented as *<0.05. C) Annexin V-Cy5/PI assay of H460 cells treated with vehicle, 20 µ M chloroquine (Chl), 4 µM compound 17, or the combination of chloroquine and C17, at the indicated concentrations for 72h. Representative flow cytometric plots for the quantification of apoptosis are shown. D) The bar graph depicts the variation of the percentage total cell death. No statistical difference was observed comparing cells treated with C17 alone or in combination with chloroquine. Values represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Under some conditions, autophagy contributes to cellular survival by providing nutrients and energy to help cells adapt to starvation or stress (such as hypoxia and anticancer drugs). However, under other conditions, activated autophagy leads to cell death, known as autophagic cell death or type II programmed cell death [53]. In order to understand whether autophagy was being induced as a survival response of cells to treatment with compound 17, we used an autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine, to evaluate whether the inhibition would alter the cytotoxic effect of compound 17. H460 cells were treated with vehicle (0.15% DMSO), 20 µ M chloroquine, 4 µM compound 17, or a combination of chloroquine and compound 17 at the indicated doses for 72h. As shown in Fig. 6C and D, the inhibition of autophagy did not affect the total cell death induced by treatment with compound 17. These data suggest that autophagy is not being induced as a resistance mechanism against treatment with compound 17 but might be induced as part of the anticancer mechanism of compound 17.

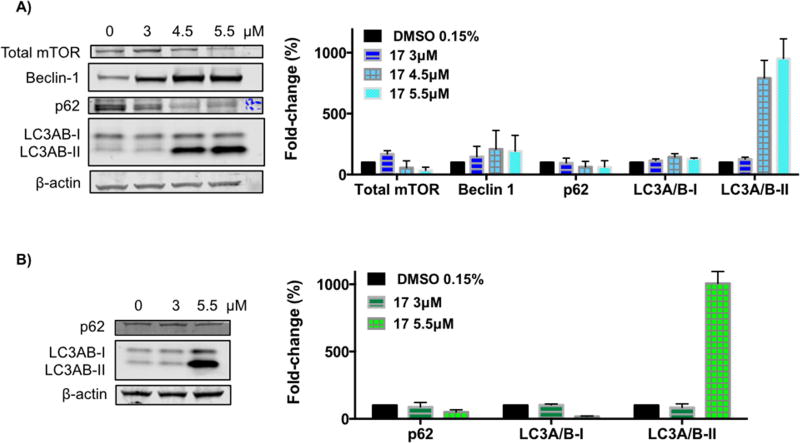

2.2.6. Effect of compound 17 on the levels of autophagy-related proteins

Acridine orange staining demonstrated autophagy induction by compound 17 treatment. Hence, key proteins that monitor autophagy were evaluated by immunoblot analysis. H460 and H322 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of compound 17 for 24h (Fig. 7). The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a major negative regulator of autophagy [55], and we found that it was decreased upon treatment with compound 17 (Fig. 7A). Beclin-1 is a central regulator of autophagy that forms a complex with vacuolar protein Vps34 and serves as a platform for recruitment of other autophagy-related genes (Atgs) that are critical for phagosome formation [55]. As shown in Fig. 7A, the expression of Beclin-1 protein in H460 cells increased upon treatment with compound 17. Interestingly to note, Beclin-1 activity in autophagy is inhibited by interaction with Bcl-2 protein, which was decreased upon treatment with compound 17 (Fig. 5A). Upon autophagy initiation, LC3A/B is cleaved and lipidated to form LC3A/B-II, which is bound to autophagosomes. Consequently, LC3A/B conversion (LC3A/B-I to LC3A/B-II) is correlated with autophagosome formation and it is commonly used to monitor autophagy [56]. Treatment with compound 17 resulted in lipidation of LC3A/B-I to LC3A/B-II as shown by the increase of a lower band (around 17 kDa) in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines (Fig. 7). The p62 protein is an ubiquitin-binding protein that functions as a receptor for cargos destined to be degraded by the cellular autophagic machinery. When autophagy is induced, the p62 protein is localized to the autophagosomes and subsequently degraded [55]. Downregulation of the p62 protein was observed with treatment using compound 17 (Fig. 7). Because p62 is selectively incorporated into the autophagosomes and is specifically degraded during autophagy, the total cellular expression of p62 was inversely correlated with autophagic activity.

Figure 7.

Effect of compound 17 on the levels of autophagy-related proteins. H460 cells (A) and H322 cells (B) were treated with compound 17 at the indicated concentrations for 24h. The levels of the indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blot. β-Actin was used as loading control. The bar graph depicts the variation of the levels of the protein expression. Values represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Several articles in the literature have reported the apoptosis- and autophagy-inducing properties of UA, in different cancer cell lines and involving different mechanisms of action [10, 11]. Moreover, the UA derivatives synthesized seem to preserve the ability to induce apoptosis, through different pathways [10]. Compound 17 appear to inherit the multitarget potential of UA and the ability to induce apoptosis and autophagy. Interestingly, while UA is able to induce both caspase-8 and caspase-9, compound 17 only induced the extrinsic pathway by activation of caspase-8.

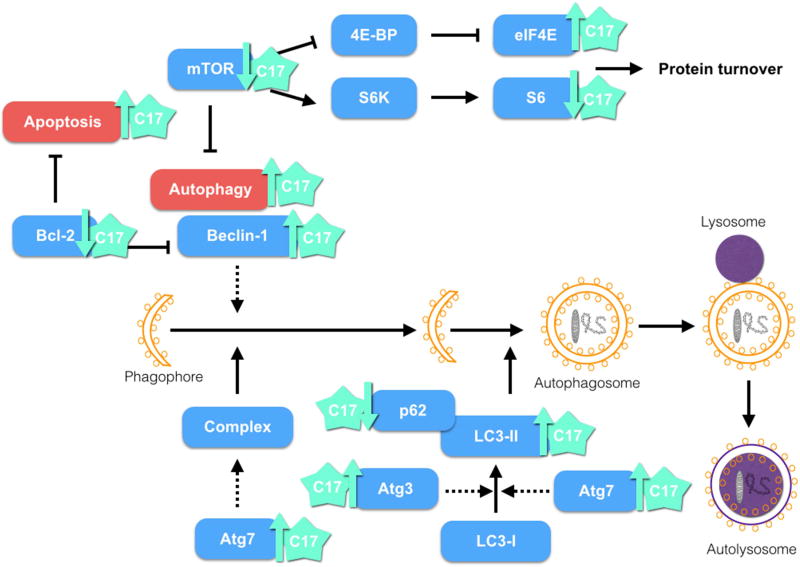

Taking together, these results are in accordance with the RPPA data, in which Beclin-1, LC3-II, Atg7 and Atg3— proteins involved in the autophagy pathway—were found upregulated by 5.6, 10.7, 4.5, and 5.1%, respectively, upon treatment of the H460 cell line with 3.5 µM compound 17 for 24h. mTOR regulates the level of S6 kinase, an enzyme partially responsible for S6 phosphorylation and activation [57, 58]. We also observed in RPPA data decreases of 11.7% and 8.4% in phosphorylated levels of S6 at S235/236 and S240/S44, respectively. EIF4E is negatively regulated by mTOR [57, 58]. The level of EIF4E pS09 was upregulated upon treatment with compound 17. These two targets of mTOR are also involved with autophagy, protein synthesis control, cell size, and ATP levels [57, 58]. H460 cells treated with compound 17 (2.5 µM and 4 µM) for 24h, 48h, and 72h did not display significant differences in cell size between control and treatment. The cell size decrease associated with S6K activity may depend on the cell types and isoform affected. Taking into account these cumulative results, a possible mechanism of action for compound 17 in the H460 cell line is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Possible mechanism of action of compound 17. Treatment of the H460 cell line with C17 showed induction of apoptosis and autophagy.

3. Conclusion

In the current study, we synthetized several derivatives of ursolic acid and screened for anti-tumor activity in NSCLC cell lines using 2D and 3D culture model systems. The most active derivatives displayed a cleaved A-ring, bearing secondary amides with small aliphatic chains (15–17). These compounds were active in both monolayer and spheroid models, with little change in their IC50 value. Compound 17 was selected for further mechanistic studies. The preliminary mechanism of action indicated that compound 17 is able to induce apoptosis via activation of caspase-8 and caspase-7, cleavage of PARP, and modulation of Bcl-2 in both NSCLC cell lines studied. Autophagy was also induced by treatment with compound 17 and could be a consequence of the decreased Bcl-2 levels, because this protein acts as an inhibitor of Beclin-1, an important regulator of autophagy activation. Given its activity and mechanism of action, this compound might represent a promising lead for the development of new anticancer agents for NSCLC.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. General

Ursolic acid and all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. The solvents used in the reactions and workups were obtained from Merck Co and VWR Portugal and were purified and dried according to usual procedures. T3P (50 wt. % in THF) was obtained as a free sample from Archimica GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was performed in Kieselgel 60HF254/Kieselgel 60G. Separation and purification of compounds by flash column chromatography (FCC) was performed using Kieselgel 60 (230–400 mesh, Merck). Melting points were measured using a BUCHI melting point B-540 apparatus and are uncorrected. IR spectra were recorded on a Fourier transform spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Digital NMR-Avance 400 apparatus spectrometer, using CDCl3 as internal standard. The chemical shifts (δ) were reported in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constants (J) in hertz (Hz). The mass spectrometry was performed using a Quadrupole/Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer (QIT-MS) (LCQ Advantage MAX, Thermo Finnigan). Elemental analysis was performed by chromatographic combustion using an Analyser Elemental Carlo Erba 1108.

4.1.2. 3 β-Hydroxy-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (2)

This compound was prepared from UA (1) according to a previously described method [35] to give 2 as a white solid (80.2%). Mp 316.8–317.6°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 4.85 (dt, J = 45.6, 8.8 Hz, 1H, H-12), 3.20 (dd, J = 11.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H, H-3), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (s, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 3H), 0.91 (s, 3H), 0.77 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3): δ = 178.88 (C28), 91.97 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, C13), 88.70 (d, J = 185.8 Hz, C12), 78.68 (C3), 55.32, 52.55 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 49.18 (d, J = 9.1 Hz), 45.19, 43.90 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 42.53, 39.53, 39.03, 38.84, 38.40, 37.12, 33.95, 31.34, 30.71, 27.92, 27.62, 27.22, 25.37 (d, J = 19.7 Hz), 22.39, 19.39, 18.50, 17.65, 17.22, 16.65, 16.46, 15.26. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 474.98 (100%) [M+H]+, 455.22 (17.50%).

4.1.3. 3-Oxo-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (3)

Prepared from 2 according to a previously described method [35] to give 3 as a white solid (24.4%). Mp 325.3 – 328.2°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 4.87 (dq, J = 46.0, 8.3 Hz, 1H, H-12), 2.60 – 2.52 (m, 1H), 2.48 – 2.41 (m, 1H), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3): δ = 216.97 (C3), 178.75 (C28), 91.91 (d, J = 14.27, C13), 89.49 (d, J = 185.77 C12), 54.83, 52.57, 48.48 (d, J = 9.33), 47.28, 45.19, 44.02 (d, J = 3.09), 42.40, 39.79, 39.55, 38.51, 36.85, 33.89, 33.37, 31.33, 30.73, 27.64, 26.58, 25.75 (d, J = 19.71), 22.39, 20.97, 19.40, 18.99, 18.17, 17.09, 16.47, 16.42. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 472.98 (100%) [M+H]+, 453.20 (44.26%).

4.1.4. 3-Oxo-4-aza-A-homo-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (4)

To a stirred mixture of 3 (250 mg, 0.53 mmol) in glacial acetic acid (7.5 ml) at 65°C, concentrated sulfuric acid (75 µl) was added. To this mixture, NaN3 (125 mg, 1.92 mmol) was added in parts over 15 min, and then the temperature was stabilized at 30°C. After 5h, cold 5% Na2CO3 aqueous solution (100 ml) was added to the reaction mixture until pH 6–7. The resulting mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 200 ml). The subsequent organic phase was washed with water (200 ml) and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (200 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 1:1 – 1:4) to give 4 as a slight yellow solid (68.6%). Mp 353.4 – 355.4°C. IR (KBr): v = 3220.54, 2977.55, 2931.27, 2871.48, 1774.19, 1666.2, 1457.92, 1392.35, 1184.08, 1120.44, 939.16 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 5.60 (s, 1H, NH), 4.82 (dm, 1H, H-12), 2.56 – 2.50 (m, 1H, H-2), 2.39 – 2.34 (m, 1H, H-2), 1.30 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.12–1.10 (6H), 0.94 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 178.77 (C28), 175.94 (CON), 92.03 (d, J = 14.6 Hz, C13), 89.73 (d, J = 186.4 Hz, C12), 56.17, 52.98, 52.72 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 49.79 (d, J = 9.5 Hz), 45.36, 44.17 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 42.44, 40.26, 39.90, 39.65, 38.75, 33.63, 33.43, 32.06, 31.42, 30.86, 27.65, 27.42, 26.30 (d, J = 19.8 Hz), 22.47, 21.99, 19.49, 19.00, 18.01, 16.99, 16.53. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 488.38 (100%) [M-H]+. Anal. Calcd for C30H46FNO3: C, 73.88; H, 9.51; N, 2.87. Found: C, 73.75; H, 9.51; N, 2.91.

4.1.5. 3-Oxo-4-oxa-A-homo-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (5)

To a stirred mixture of 3 (300 mg, 0.63 mmol) in CHCl3 (10 ml), protected from light and at r.t., m-CPBA 77% (329 mg, 1.47 mmol) was added. Additional m-CPBA 77% was added (329 mg, 1.90 mmol, e.a.) at 24h and 48h. After 120h, the reaction mixture was diluted with CHCl3 (10 ml) and washed with 5% Na2SO3 aqueous solution (20 ml). The aqueous solution was extracted twice with CHCl3 (50 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with 10% NaHCO3 aqueous solution (50 ml), water (50 ml), and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (50 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (toluene:diethyl ether 2:1 – 1:3) to give 5 as a white solid (399.3 mg, 66.6%). Mp 240.5 – 243.5°C. IR (KBr): ν = 2971.77, 2931.27, 2875.34, 1764.55, 1731.76, 1457.52, 1392.35, 1280.50, 1147.44 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 4.83 (dq, J = 45.6, 8.3 Hz, 1H, H-12), 2.70 – 2.62 (m, 1H, H-2), 2.57 – 2.51 (m, 1H, H-2) 1.48 (s, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.27 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 2.59H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.12 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 178.74 (C28), 174.74 (C3), 92.02 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, C13), 89.51 (d, J = 186.5 Hz, C12), 85.80 (C4), 53.01, 52.74 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 49.79 (d, J = 9.3 Hz), 45.38, 44.24 (d, J = 2.7 Hz), 42.31, 40.34, 39.68, 39.55, 38.82, 33.33, 32.33, 31.43, 31.20, 30.88, 27.68, 26.77, 26.40 (d, J = 19.9 Hz), 22.91, 22.48, 19.50, 19.09, 17.78, 16.98, 16.52. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 489.08 (100%) [M+H]+, 469.26 (26%). Anal. Calcd. For C30H45FO4·0.2H20: C, 73.19; H, 9.3. Found: C, 72.99; H, 9.3.

4.1.6. 3,4-Seco-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olid-3-oic acid (6)

To a mixture of 5 (475 mg, 0.97 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (30 ml), at r.t., p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (1.56 g, 7.89 mmol) was added. After 24h, the mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 ml) and water (20 ml). The aqueous phase was extracted twice with CH2Cl2 (50 ml). The organic phase was washed with 5% NaHCO3 aqueous solution (2 × 50 ml), water (50 ml), and 10% NaCl aqueous solution, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 5:1 – 3:1) to give 6 as a white solid (68.4%). Mp 230 – 234.6 °C. IR (KBr): ν = 3284.18, 3068.19, 2979.48, 2948.63, 2923.56, 2875.34, 1764.55, 1741.41, 1704.76, 1633.41 1459.85, 1392.35, 1189.86, 1143.58, 937.23 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 4.88 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.83 (dm, 1H, H-12), 4.67 (s, 1H, H-23), 2.44 – 2.37 (m, 1H, H-2), 2.25 – 2.17 (m, 1H, H-2), 1.73 (3H, H-24), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 3H), 0.92 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3): δ = 179.71 (COOH), 179.02 (C28), 146.85 (C=CH2), 114.26 (C=CH2), 92.16 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, C13), 89.46 (d, J = 186.4 Hz, C12), 52.72 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 50.43, 45.37, 44.50 (d, J = 2.4 Hz), 42.34, 39.70, 39.71 (d, J = 9.3 H), 39.58, 38.71, 34.05, 32.75, 31.47, 30.88, 28.74, 27.78, 25.95 (d, J = 19.2 Hz), 23.90, 23.09, 22.53, 20.72, 19.55, 18.42, 17.19, 16.71. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 488.99 (100%) [M+H]+, 469.23 (44%). Anal. Calcd. For C30H45FO4: C, 73.73; H, 9.28. Found: C, 73.55; H, 9.52.

4.1.7. 3,4-Seco-3-amide-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (7)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (140 mg, 0.29 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (3 ml), at r.t., oxalyl chloride (0.2 ml, 1.52 mmol) was added. After 15h, the reaction mixture was evaporated and the resulting residue was dissolved in dry THF (15 ml) and cold 25% ammonium aqueous solution (12 ml) was added dropwise. After 2h, the reaction mixture was evaporated and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 60 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with 1M HCl aqueous solution (60 ml), water (60 ml), and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (60 ml) and dried over Na2SO4. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatograph (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 7:1 – 1:1) to give 7 as a white solid (74,8%). Mp 124.2 – 128.6°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3355.53, 3075.9, 2973.7, 2929.34, 2871.49, 1772.26, 1670.05, 1616.06, 1457.92, 1390.42, 1186.01, 1141.65, 937.23 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 5.79 (br s, 2H, NH2) 4.87 (dq, J = 45.7, 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.87 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.67 (s, 1H, H-23), 1.73 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 3H), 0.92 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 179.04 (C28), 176.14 (CON), 147.33 (C=CH2), 114.13 (C=CH2), 92.20 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, C13), 89.39 (d, J = 185.6 Hz, C12), 52.74 (d, J = 3.4 Hz), 50.67, 45.36, 44.50 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 42.35, 39.71 (2C), 39.71 (d, J = 9.2 Hz) 38.72, 35.17, 32.75, 31.48, 30.88, 30.47, 27.78, 26.03 (d, J = 19.2 Hz), 23.88, 22.90, 22.54, 20.81, 19.55, 18.45, 17.19, 16.73. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 488.24 (100%) [M-H]+, 487.23 (37%), 468.32 (16%). Anal. Calcd for C30H46FNO3˙0.8H2O: C, 71.76; H, 9.56; N, 2.79. Found: C, 71.47; H, 9.59; N, 2.66.

4.1.8. 3,4-Seco-3-cyano-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (8)

To a stirred mixture of 7 (300 mg, 0.62 mmol) in EtOAc (3 ml), THF (1 ml), and Et3N (0.3 ml) under N2, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.7 ml) was added dropwise. The solution was heated under reflux. After 5h, the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc (80 ml) and water (35 ml). The aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (2 × 70 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with water (70 ml) and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (70 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 8:1 – 1:3) to give 8 as a slight yellow solid (50.5%). Mp 251.2 – 255.2°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3072.05, 2979.48, 2931.27, 2867.63, 2237.02, 1768.4, 1633.41, 1452.14, 1392.35, 1238.08, 1133.94, 933.38 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 5.10 (dq, J = 45.10, 8.30 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.88 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.63 (s, 1H, H-23), 2.34 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, CNCH2), 1.71 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 3H), 0.92 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 178.97 (C28), 146.57 (C=CH2), 120.39 (CN), 114.61 (C=CH2), 92.01 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, C13), 88.48 (d, J = 186.0 Hz, C12), 52.75 (d, J = 3.0 Hz), 50.38, 45.29, 44.46 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 42.34, 39.90, 39.70, 39.27 (d, J = 9.8 Hz), 38.68, 34.06, 32.55, 31.46, 30.89, 27.66, 26.21 (d, J = 19.6 Hz), 23.64, 22.67, 22.51, 20.35, 19.57, 18.47, 16.99, 16.53, 11.67. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 469.92 (100%) [M-H]+, 450.15 (16.51%). Anal. Calcd for C30H44FNO2·0.6H2O: C, 74.99; H, 9.48; N, 2.92. Found: C, 74.79; H, 9.33; N, 2.59.

4.1.9. 3,4-Seco-3-N-phenylamide-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (9)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (125 mg, 0.26 mmol) in dry THF (2 ml), aniline (0.03 ml, 0.31 mmol), and Et3N (0.07 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.4 ml) was added dropwise. After 7.3h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 ml) from water (20 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with 5% HCl aqueous solution (2 × 60 ml), water (60 ml), and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (60 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 13:1 – 7:1) to give 9 as a white solid (74.1%). Mp 267.1 – 270.8°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3342.03, 3289.96, 3133.76, 3072.05, 2971.77, 2931.27, 2875.34 1749.12, 1687.41, 1600.63, 1540.84, 1438.64, 1386.57, 1305.57, 1243.86, 1143.58, 937.23, 754.03, 692.32 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 7.52 – 7.50 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.32 – 7.29 (m, 3H, H-Ar), 7.10 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.91 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.85 (dt, J = 43.1, 8.5 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.73 (s, 1H, H-23), 1.76 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.04 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (s, 3H), 0.94 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 179.09 (C28), 171.31 (CON), 147.61 (C=CH2), 137.97 (C-Ar), 129.15 (C-Ar, 2C), 124.44 (C-Ar), 119.85 (C-Ar, 2C), 114.10 (C=CH2), 92.6 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, C13), 89.22 (d, J = 186.0 Hz, C12), 52.73 (d, J = 3.4 Hz), 50.75, 45.35, 44.48 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 42.40, 39.91, 39.78 (d, J = 9.8 Hz), 39.68, 38.69, 35.23, 32.79, 32.58, 31.49, 30.89, 27.77, 26.15 (d, J = 19.4 Hz), 23.92, 22.92, 22.54, 20.79, 19.54, 18.46, 17.15, 16.52. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 564.41 (100%) [M-H]+. Anal. Calcd for C36H50FNO3: C, 76.69; H, 8.94; N, 2.48. Found: C, 76.66; H, 8.95; N, 2.56.

4.1.10. 3,4-Seco-3-N-phenethylamide-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (10)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (100 mg 0.20 mmol) in dry THF (2 ml), phenethylamine (0.03 ml, 0.25 mmol), and Et3N (0.06 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50% wt. % in THF) (0.16 ml) was added dropwise. At 2.75h, Et3N (0.06 ml) and T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.16 ml) were added. After 4h, Et3N (0.06 ml) and T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.16 ml) were added. After 6 h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 ml) from water (20 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with water (50 ml) and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (50 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 8:1 – 1:1) to give 10 as a white solid (72%). Mp 101.3 – 104.0°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3326.6, 3066.26, 3025.76, 2954.41, 2929.34, 2871.49, 1388.50, 1238.08, 1133.94, 1774.19, 1650.77, 1540.84, 1536.95, 1455.99, 937.23, 748.25, 700.03 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 7.33 – 7.30 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.25 – 7.18 (m, 3H, H-Ar), 5.45 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.85 (dm, 1H, H-12), 4.81 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.62 (s, 1H, H-23), 3.65 – 3.36 (m, 2H, CH2N), 2.82 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, ArCH2), 1.71 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 3H), 0.89 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3): δ = 178.85 (C28), 172.86 (CON), 147.31 (C=CH2), 138.79 (C-Ar), 128.78 (C-Ar, 2C), 128.67 (C-Ar, 2C), 126.57 (C-Ar), 113.85 (C=CH2), 92.02 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, C13), 89.17 (d, J = 186.0 Hz, C12), 52.60 (d, J = 3.3 Hz), 50.49, 45.23, 44.37 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 42.21, 40.58, 39.59 (2C), 39.53 (m), 38.60, 35.59, 35.41, 32.63, 31.37, 31.30, 30.78, 27.66, 25.85 (d, J = 18.5 Hz), 23.77, 22.78, 22.42, 20.71, 19.43, 18.32, 17.05, 16.55. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 592.33 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C38H54FNO3: C, 77.12; H, 9.20; N, 2.37. Found: C, 77.40; H, 9.12; N, 2.34.

4.1.11. 3,4-Seco-3-N-(4-methylbenzylamide)-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (11)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (250 mg, 0.51 mmol) in dry THF (3.5 ml), 4-methylbenzylamine (0.08 ml, 0.61 mmol), and Et3N (0.14 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.4 ml) was added dropwise. After 5 h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 80 ml) from water (35 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with water (80 ml) and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (80 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 6:1 – 2:1) to give 11 as a white solid (46.5%). Mp 100.4 – 103.45°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3326.60, 3070.12, 2956.34, 2927.41, 2871.49, 1774.19, 1650.77, 1540.84, 1457.92, 1388.50m, 1238.08, 1133.94, 937.23, 804.17 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 7.18 – 7.14 (m, 4H, H-Ar), 5.72 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.89 (dq, J = 45.6, 8.8 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.86 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.67 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.38 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H, CH2N), 2.34 (s, 3H, CH3-Ar), 1.73 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 3H), 0.91 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3): δ = 179.01 (C28), 172.79 (CON), 147.34 (C=CH2), 137.51 (C-Ar), 135.25 (C-Ar), 129.57 (CAr, 2C), 128.07 (C-Ar, 2C), 114.12 (C=CH2), 92.20 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, C13), 89.30 (d, J = 186.5 Hz, C12), 52.74 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 50.52, 45.36, 44.51 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 43.68, 42.34, 39.77, 39.72 (2C), 39.63, 38.73, 35.37, 32.77, 31.49, 31.37, 30.90, 27.78, 26.03 (d, J = 19.2 Hz), 23.92, 23.02, 22.55, 21.23, 20.82, 19.55, 18.44, 17.17, 16.69. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 592.36 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C38H54FNO3·0.85H2O: C, 75.17; H, 9.25; N, 2.31. Found: C, 74.87; H, 8.98; N, 2.13.

4.1.12. 3,4-Seco-3-N-(4-fluorobenzylamide)-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (12)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (150 mg, 0.31 mmol) in dry THF (2 ml), 4-fluorobenzylamine (0.04 ml, 0.37 mmol), and Et3N (0.05 ml) at 3–5 °C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.24 ml) was added dropwise. After 4 h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 ml) from water (10 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with 5% HCl aqueous solution (50 ml), water (50 ml), and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (50 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness to give 12 as a white solid (87.5%). Mp 119.2 – 123.1 °C. IR (KBr): ν = 3342.03, 3072.05, 2956.34, 2929.34, 2871.49, 1174.19, 1650.77, 1509.99, 1457.92, 1390.42, 1222.65, 1133.94, 937.23, 823.46 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 7.26 – 7.23 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.02 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, H-Ar), 5.82 (br s, 1H, NH), 4.88 (dq, J = 45.9, 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.85 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.67 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.39 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, CH2N), 1.73 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 3H), 0.91 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 179.01 (C28), 173.01 (CON), 162.25 (d, J = 246.7 Hz, CF-Ar), 147.38 (C=CH2), 134.13 (d, J = 3.03 Hz, C-Ar), 129.70 (d, J = 8.13 Hz, 2C, C-Ar), 115.74 (d, J = 21.32 Hz, 2C, C-Ar), 114.10 (C=CH2), 92.18 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, C13), 89.31 (d, J = 186.1 Hz, C12), 52.74 (d, J = 3.5 Hz), 50.58, 45.36, 44.51 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 43.16, 42.35, 39.77, 39.72, 39.66, 38.73, 35.42, 32.76, 31.49, 31.34, 30.89, 27.78, 26.04 (d, J = 19.0 Hz), 23.90, 22.97, 22.54, 20.82, 19.55, 18.43, 17.18, 16.69. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 596.32 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C37H51F2NO3: C, 74.59; H, 8.63; N, 2.35. Found: C, 74.69; H, 8.58; N, 2.16.

4.1.13. 3,4-Seco-3-N-(2-methoxyphenethylamide)-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (13)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (335mg, 0.69 mmol) in dry THF (4 ml), 2-methoxyphenethylamine (0.12 ml, 0.82 mmol), and Et3N (0.19 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.89 mmol) was added dropwise. At 2h, Et3N (1.37mmol) and T3P 50% (m/m) in THF (0.5 ml) were added. After 5 h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 80 ml) from water (35 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with 5% HCl aqueous solution (80 ml), water (80 ml), and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (80 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 7:1 – 2:1) to give 13 as a white solid (46.8%). Mp 100.4 – 103.45°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3318.89, 3072.05, 2954.41, 2929.34, 2871.49, 1774.19, 1646.91, 1540.84, 1494.56, 1457.92, 1388.50, 1243.86, 1133.94, 937.23, 754.03 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 7.23 (td, J = 7.9, 1.7 Hz, 1H, H-Ar), 7.12 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H, H-Ar), 6.94 – 6.85 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 5.78 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H, NH)), 4.86 (dq, J = 45.5, 8.8 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.83 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.63 (s, 1H, H-23), 3.84 (s, 3H, CH3O-Ar), 3.50 – 3.46 (m, 2H, CH2N), 2.84 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-CH2), 1.71 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 3H), 0.89 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 179.03 (C28), 173.35 (CON), 157.54 (C-Ar), 147.29 (C=CH2), 130.86 (C-Ar), 128.15 (C-Ar), 127.42 (C-Ar), 121.05 (C-Ar), 114.07 (C=CH2), 110.70 (C-Ar), 92.22 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, C13), 89.22 (d, J = 185.9 Hz, C12), 55.59, 52.74 (d, J = 3.5 Hz), 50.42, 45.36, 44.51 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 42.32, 40.36, 39.72 (2C), 39.55 (d, J = 9.8 Hz), 38.73, 35.23, 32.74, 31.50, 31.16, 30.91, 29.98, 27.78, 25.95 (d, J = 19.4 Hz), 23.92, 23.06, 22.55, 20.89, 19.56, 18.44, 17.17, 16.65. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 622.38 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C39H56FNO4·0.2H2O: C, 74.89; H, 9.09; N, 2.24. Found: C, 74.70; H, 9.06; N, 2.30.

4.1.14. 3,4-Seco-3-N-(3-chlorophenylethylamide)-4 (23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (14)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (125mg, 0.26 mmol) in dry THF (2 ml), 2-(3-chlorophenyl)ethylamine (0.04 ml, 0.31 mmol), and Et3N (0.14 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.4 ml) was added dropwise. After 5h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 60 ml) from water (25 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with 5% HCl aqueous solution (60 ml), water (60 ml), and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (60 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 7:1 – 2:1) to give 14 as a white solid (88.8%). Mp 101.7 – 105.0°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3330.46, 3070.12, 2954.41, 2929.34, 2871.49, 1774.19, 1650.77, 1598.70, 1540.84, 1457.92, 1390.42, 1238.08, 1133.94, 937.22, 782.96, 698.10, 664.61 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 7.25 – 7.22 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.17 (s, 1H, H-2’-Ar), 7.07 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, H-Ar), 5.47 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.86 (dm, 1H, H-12), 4.82 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.62 (s, 1H, H-23), 3.60 – 3.41 (m, 2H, CH2N), 2.80 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, ArCH2), 1.71 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 3H), 0.90 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 178.84 (C28), 172.95 (CON), 147.37 (C=CH2), 140.89 (C-Ar), 134.40 (CAr), 129.91 (C-Ar), 128.93 (C-Ar), 126.96 (C-Ar), 126.77 (C-Ar), 113.84 (C=CH2), 92.03 (d, J =14.3 Hz, C13), 89.18 (d, J = 186.0 Hz, C12), 53.86, 52.60 (d, J = 3.4 Hz), 50.53, 45.22, 44.37 (d, J = 3.0 Hz), 42.22, 40.41, 39.72, 39.68 (d, J = 8.5 Hz), 38.60, 35.45, 35.30, 32.63, 31.37, 31.30, 30.77, 27.66, 25.86 (d, J = 19.7 Hz), 23.75, 22.73, 22.42, 20.69, 19.43, 18.32, 17.05, 16.56. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 626.22 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C38H53ClFNO3: C, 72.88; H, 8.53; N, 2.24. Found: C, 72.86; H, 8.53; N, 2.25.

4.1.15. 3,4-Seco-3-N-methylamide-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (15)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (250 mg, 0.51 mmol) in dry THF (3 ml), methylamine solution (33 wt. % in absolute ethanol) (0.07 ml, 0.56 mmol), and Et3N (0.14 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.4 ml) was added dropwise. After 5 h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 80 ml) from water (35 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with water (45 ml) and 10% NaCl aqueous solution, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 6:1 – 2:1) to give 15 as a white solid (52,4%). Mp 151.2 – 155.3°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3278.39, 3085.55, 2956.34, 2929.34, 2871.49, 1774.19, 1639.20, 1563.99, 1457.92, 1390.42, 1236.15, 1133.94, 937.23 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3): δ = 5.65 (br s, 1H, NH), 4.86 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.85 (dq, J = 44.8, 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.68 (s, 1H, H-23), 2.81 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 3H, NCH3), 1.73 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 3H), 0.91 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3): δ = 179.06 (C28), 173.97 (CON), 147.34 (C=CH2), 114.10 (C=CH2), 92.24 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, C13), 89.30 (d, J = 186.3 Hz, C12), 52.75 (d, J = 3.4 Hz), 50.50, 45.37, 44.52 (d, J = 2.7 Hz), 42.35, 39.79, 39.73, 39.62 (d, J = 9.5 Hz), 38.73, 35.37, 32.76, 31.50, 31.08, 30.89, 27.78, 26.63, 26.03 (d, J = 19.3 Hz), 23.92, 23.00, 22.55, 20.86, 19.55, 18.44, 17.17, 16.65. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 502.28 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C31H48FNO3·0.2H2O: C, 73.68; H, 9.65; N, 2.77. Found: C, 73.35; H, 10.02; N, 2.60.

4.1.16. 3,4-Seco-3-N-ethylamide-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (16)

To a stirred solution of 6 (250 mg, 0.51 mmol) in dry THF (3.5 ml), ethylamine solution (2.0 M in THF) (0.3 ml, 0.60 mmol) and Et3N (0.14 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.4 ml) was added dropwise. After 3h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 80 ml) from water (35 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with water (2 × 90 ml) and 10% NaCl aqueous solution (90 ml), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 6:1 – 1:3) to give 16 as a white solid (51.7%). Mp 108.5 – 112.5 °C. IR (KBr): ν = 3268.11, 3081.69, 2971.77, 2931.27, 2873.42, 1774.19, 1635.34, 1556.27, 1457.92, 1390.42, 1238.08, 1133.94, 937.23. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 5.53 (m, 1H, NH), 4.86 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.84 (dq, J = 45.8, 8.1 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.67 (s, 1H, H-23), 3.32 – 3.22 (m, 2H, CH2N), 1.73 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.15 – 1.12 (m, 6H), 0.96 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 3H), 0.91 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 179.05 (C28), 172.92 (CON), 147.40 (C=CH2), 114.05 (C=CH2), 92.23 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, C13), 89.28 (d, J = 185.6 Hz, C12), 52.73 (d, J = 3.1 Hz), 50.49, 45.36, 44.50 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 42.33, 39.76, 39.72, 39.62 (d, J = 9.7 Hz), 38.72, 35.42, 34.61, 32.76, 31.49, 31.39, 30.89, 27.77, 26.02 (d, J = 19.2 Hz), 23.96, 23.93, 23.02, 22.54, 20.84, 19.54, 18.43, 17.16, 16.64, 14.96. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 516.34 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C32H50FNO3·0.8H2O: C, 72.50; H, 9.81; N, 2.64. Found: C, 72.20; H, 9.86; N, 2.37.

4.1.17. 3,4-Seco-3-N-propylamide-4(23)-en-12 β-fluor-urs-13,28 β-olide (17)

To a stirred mixture of 6 (250 mg, 0.51 mmol) in dry THF (4 ml), propylamine (0.05 ml, 0.61 mmol), and Et3N (0.14 ml) at 3–5°C, T3P (50 wt. % in THF) (0.4 ml) was added dropwise. After 5 h, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 80 ml) from water (35 ml). The resulting organic phase was washed with water (45 ml) and 10% NaCl aqueous solution, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate 6:1 – 1:2) to give 17 as a white solid (62.1%). Mp 110.3 – 116.1°C. IR (KBr): ν = 3270.68m, 3079.76, 2962.12, 2931.27, 2873.42, 1774.19, 1641.13, 1544.70, 1457.92, 1388.50, 1238.08, 1133.94, 937.23 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 5.59 (br s, 1H, NH), 4.87 (s, 1H, H-23), 4.86 (dq, J = 45.5, 8.3 Hz, 1H, H-12), 4.68 (s, 1H, H-23), 3.23 – 3.19 (m, 2H, CH2N), 1.74 (s, 3H, H-24), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 3H), 0.94 – 0.89 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 179.05 (C28), 173.25 (CON), 147.48 (C=CH2), 114.05 (C=CH2), 92.23 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, C13), 89.32 (d, J = 186.1 Hz, C12), 52.74 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 50.54, 45.37, 44.51 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 42.35, 41.57, 39.78, 39.73, 39.63 (d, J = 9.7 Hz), 38.73, 35.50, 32.76, 31.50, 31.35, 30.90, 27.79, 26.02 (d, J = 19.4 Hz), 23.92, 22.97, 22.94, 22.56, 20.87, 19.56, 18.45, 17.18, 16.67, 11.49. MS (DI-ESI) (m/z): 530.34 (100%) [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C33H52FNO3·0.2EtOAc: C, 74.16; H, 9.87; N, 2.56. Found: C, 74,00; H, 10,15; N, 2.19.

4.2. Biology

4.2.1. Cell lines and culture

H460 CTR5, H460 LKB1/5+/+, and H322 (NSCLC) cell lines were obtained from Dr. John Heymach at MD Anderson Cancer Center. H460 CTR5, H460 LKB1+/+, and H322 cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Corning Cellgro) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and were cultured at 37°C in CO2 incubators. These cell lines were authenticated using an AmpF/STR Identification Kit (Applied Biosystems) and routinely tested for Mycoplasma contamination using a MycoTect kit (Invitrogen). Experiments were conducted in cells with fewer than 18 passages and maintained at a logarithmic growth concentration between 105 cells/ml and 106 cells/ml as determined by a Coulter Channelyzer (Beckman Coulter) with less than 10% endogenous cell death confirmed by flow cytometry.

4.2.2. Materials

UA derivatives were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 20 mM and stored at −80°C. To obtain final assay concentrations, the stock solutions were diluted in culture medium. The final concentration of DMSO in working solution was always 0.15%. Bafilomycin A1 (B1793) and chloroquine (C6628) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Annexin V-Cy5 and PI were obtained from BD Biosciences Pharmingen. Primary antibodies against caspase 8 (1C12), caspase 3 (8G10), caspase 7 (#9492), LC3A/B (D3U4C) XP, and total mTOR (4517) were obtained from Cell Signaling. Primary antibody against Bcl2 (clone 124) was obtained from Dako. Beclin-1 (NB500-266SS) and GAPDH (NB600-502) were purchased from Novus Biologicals. Antibody against β-actin (AC-15) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Primary antibody against Mcl-1 (s-19) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Primary antibody against PARP (4C10-5) was purchased from BD Pharmigen. Primary antibody against p62 (BML-PW9860) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences. Secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse (926-68070) and goat anti-rabbit (926-32211) were obtained from LI-COR Biosciences.

4.2.3. Viability assay

For the monolayer culture model, cells were seeded in a 384-well black polystyrene Greiner plate at densities of 850 cells/well for H460 CTR5, 660 cells/well for H460 LKB1/5+/+, and 1780 cells/well for H322 in RPMI-1640 (10% FBS). The cell density was determined based on the size and cell growth characteristics of each cell line, in order for the cell density at the end point to be 70–80% of the well surface. Cells were treated with 0.15% DMSO or different concentrations of each drug. After 72h of treatment, 5 µl (384-well plate) of CellTiter-Blue® Viability assay (Promega) was added to each well and incubated until color change was observed (50–60 min for H460 CTR5, 80–90 min for H460 LKB1/5, and 100–120 min for H322). The fluorescence was measured at 590 nm using a PHERAstar plate reader. Concentrations that inhibited cell growth by 50% (IC50) were determined by nonlinear regression with GraphPad Prism software 6.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

For the spheroid culture model, H460 CTR5 and H322 cells were grown at 495 cells/well and 650 cells/well, respectively, using a round-bottom, ultralow attachment 96-well plate (Corning® Costar® Ultra-low attachment multiwall plates, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO or different concentrations of each drug. After 96h of treatment, volumes were adjusted to the same level, 100 µl of CellTiter-Glo® Luminescence Viability assay (Promega) was added, plates were sealed and shaken for 20 min at speed 10, and then incubated for 10 min before luminescence was measured using a PHERAstar plate reader at 560 nm. Concentrations that inhibited cell growth by 50% (IC50) were determined by nonlinear regression with GraphPad Prism software 6.2.

4.2.4. Macromolecule synthesis assay

Global DNA, RNA, and protein syntheses were measured using [3H]thymidine, [3H]uridine, and [3H]leucine incorporation assays, respectively. Cells were plated in a six-well plate (0.55 × 105 cells/well, 24h treatment, and 0.15 × 105 cells/well, 48h treatment, H460 CTR5 cell line, 1 ml RPMI-1640–10% FBS) and after 24h, cells were treated with DMSO alone or with drugs (in 1 ml of RPMI-1640–10% FBS, total volume 2 ml) for 24h and 48h. Afterwards, 20 µl of [methyl-3H]thymidine, 10 µl of [5,6-3H]uridine, or 20 µl of [4,5-3H]L-leucine (each isotope was diluted 1:10 times from the original concentration stock (1.0 mCi/ml), in water, Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA) per well was added and incubated for an additional 60 min at 37°C. Cultures were treated with 2 ml of cold PBS, supernatant was collected, and cells were harvested by trypsinization. Each sample was poured into a filter (glass fiber filters, 2.7 cm, wet with 1% (m/v) Na4P2O4·10H2O) in a manifold, washed with cold 0.4N PCA (5 ml) and rinsed with 70% EtOH and 100% EtOH. Each dried filter was added to a scintillation vial and 7 ml of scintillation fluid was added. Radioactivity (dpm) was counted using a liquid scintillation counter (instrument series 1900CA, Packard).

4.2.5. Annexin V-Cy5/PI flow cytometric assay

Apoptosis was measured by using the annexin V/PI flow cytometric assay. Cells were plated in a six-well plate (0.085 × 105 cells/well, H460 CTR5 cell line, 2 ml of RPMI-1640– 10% FBS), and after 24h, cells were treated with DMSO alone or with drugs (in 1 ml of RPMI-1640–10% FBS, total volume 3 ml) for 72h. Cells were harvested by trypsinization, collected by centrifuge, washed with PBS, and collected as a pellet. The pellet was resuspended in annexin V-Cy5/buffer solution (5 µl of annexin V-Cy5 in annexin binding buffer ×10) and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. Propidium iodide solution (10 µl PI (50 µg/ml) + 300 µl annexin binding buffer) was added just before analysis using a BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data from 1 × 104 cells per sample were collected and analyzed.

4.2.6. Acridine orange staining

As a marker of autophagy, acidic vesicular organelles were quantified by acridine orange staining. Cells were plated onto six-well plates (0.095 × 105 cells/well, H460 CTR5 cell line, 2 ml of RPMI-1640–10% FBS) and after 24h, cells were treated with DMSO alone, drugs, or medium alone (in 1 ml of RPMI-1640–10% FBS, total volume 3 ml) for 72h. 30 min prior to staining, 1 µl of 160 µM bafilomycin A1 was added to the untreated well (medium only) as a negative control, and samples were incubated at 37°C. Afterwards, 3 µl of acridine orange stain (10 mg/ml stock) (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was added to each sample and incubated at 37°C for 15 min in the dark. The medium was collected, and cells were harvested using Accumax cell dissociation solution in DPBS, using RPMI-1640 with no phenol red (Gibco Life Technologies) to stop the reaction, and centrifuged. The pellet was washed with PBS, centrifuged, and re-suspended in RPMI-1640 without phenol red. Accumulation of acidic vesicles was quantified as the red/green (FL3/FL1) fluorescence ratio using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer.

4.2.7. Protein extraction and immunoblot assay

To prepare the total protein extracts, H650 CTR5 cells (3 × 105) and H322 cells (4.2 × 105) were seeded in a 100 mm × 20 mm dish (10 ml of RPMI-1640–10% FBS) and incubated at 37°C. After 24h, cells were treated with DMSO or different concentrations of drug (in 5 ml of RPMI-1640–10% FBS, total volume 15 ml) for 24h. After treatment, medium was collected and cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with PBS, centrifuged, lysed using cold 1× RIPA buffer (1 ml of 10× RIPA lysis buffer, one tablet of PhosStop phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, and one tablet of cOmplete mini protease inhibitor cocktail), and sonicated for 4 min with 30-second intervals at 4°C. Lysed cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 13000 rpm, and supernatant was carefully removed. All steps were performed on ice. Protein concentration of the lysate was determined using a DC™ protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). 5 µl of lysate was added to a 96-well plate followed by the addition of 25 µl of working solution A-S (20 µl reagent S to each milliliter of reagent A needed for the assay) plus the addition of 200 µl of reagent B. The plate reading was taken at 750 nm (Powerwave XS, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc.) using known standards; unknown concentrations of protein lysates were determined using Gen5™ software (BioTek). 30 µg of protein lysates was boiled with loading buffer SDS-PAGE with 10% 2-mercaptoethanol at 95°C for 10 min. Prepared lysate buffer solutions were electrophoresed on Criterion Bis-Tris gel (4–10% or 12%) using 1× MOPS or 1× MES running buffer. Afterwards, proteins were transferred from the gel to membrane nitrocellulose (Li-COR Biosciences) or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF, RMD Millipore), this membrane was pre-treated with methanol), using a transfer buffer solution (800 ml Millipore water, 100 ml methanol, 100 ml 10× transfer buffer (30 g Tris-base, 144 g glycine for 1 liter of Millipore water)) at 75V for 50 min on ice. After transfer, PVDF membrane was dried for 1h, wet with methanol, and washed with PBS. PVDF and nitrocellulose membranes were first blocked with Odyssey® blocking buffer solution for 1h at room temperature and then probed with primary antibodies overnight at 3–8°C. Membranes were washed twice for 10 min with 0.1% Tween 20 (in PBS) and then one time with PBS and probed with infrared-labeled secondary antibody (1:10000 dilution, LI-COR Inc.) for 1h at room temperature. Membranes were again washed as before and scanned using the LI-COR Odyssey CLx Infrared Imager.

4.2.8. Data and statistical analysis

All cell line data were analyzed in triplicate and are presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). All data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism 6.2 software. Protein levels were quantified using Odyssey software for the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Inc.) and then normalized to DMSO control using GraphPad Prism software. The ratio of protein to GAPDH or to β-actin was calculated for the immunoblot analyses. For statistical analysis, most data were analyzed by the Student’s paired/unpaired t test, as described in the respective figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

➢

A series of new A-ring cleaved ursolic acid derivatives was synthesized

-

➢

The new derivatives were evaluated against NSCLC cell lines

-

➢

Compound 17 was the most active among all tested derivatives

-

➢

Compound 17 was active in both 2D and 3D culture models

-

➢

Studies revealed that compound 17 induces apoptosis and autophagy

Acknowledgments

Vanessa I. S. Mendes thanks Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology) (FCT) for financial support (SFRH/BD/77419/2011). Jorge A. R. Salvador thanks Universidade de Coimbra for financial support. The authors are thankful to the Jack A. Laughery Family Trust for research support. The authors would like to acknowledge MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) (CA016672) and Ms Tracy Stafford for critically editing the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the UC-NMR facility, which is supported in part by FEDER – European Regional Development Fund through the COMPETE Programme (Operational Programme for Competitiveness) and by National Funds through FCT through grants REEQ/ 481/QUI/2006, RECI/QEQ-QFI/0168/2012, CENTRO-07-CT62- FEDER-002012, and Rede Nacional de Ressonância Magnética Nuclear (RNRMN), for NRM data. The authors would like to acknowledge the Laboratory of Mass Spectrometry (LEM) of the Node UC integrated in the National Mass Spectrometry Network (RNEM) of Portugal, for the MS analyses. The authors are grateful for the financial support by FEDER, COMPETE 2020 and FCT (strategic project UID/NEU/04539/2013). The authors would like to acknowledge Centro de Apoio Científico e Tecnolóxico á Investigación (C.A.C.T.I.), Universidade de Vigo, Campos Lagoas – Marcosende, 15, 36310 Vigo, for elemental analysis. The authors would also like to thank Archimica GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany, for providing T3P® (50 wt. % in THF) as a free sample.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wood SL, Pernemalm M, Crosbie PA, Whetton AD. Molecular histology of lung cancer: from targets to treatments. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2015;41:361–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reck M, Heigener DF, Mok T, Soria J-C, Rabe KF. Management of non-small-cell lung cancer: recent developments. Lancet. 2013;382:709–719. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rami-Porta R, Crowley JJ, Goldstraw P. The Revised TNM Staging System for Lung Cancer. Annals of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2009;15:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012, International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO; 2012. [accessed May 16, 2016]. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liby KT, Yore MM, Sporn MB. Triterpenoids and rexinoids as multifunctional agents for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2007;7:357–369. doi: 10.1038/nrc2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sporn MB, Liby K, Yore MM, Suh N, Albini A, Honda T, Sundararajan C, Gribble GW. Platforms and networks in triterpenoid pharmacology. Drug Development Research. 2007;68:174–182. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cragg GM, Grothaus PG, Newman DJ. Impact of natural products on developing new anti-cancer agents. Chemical Reviews. 2009;109:3012–3043. doi: 10.1021/cr900019j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J. Pharmacology of oleanolic acid and ursolic acid. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1995;49:57–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvador JAR, Moreira VM, Goncalves BM, Leal AS, Jing Y. Ursane-type pentacyclic triterpenoids as useful platforms to discover anticancer drugs. Natural Product Reports. 2012;29:1463–1479. doi: 10.1039/c2np20060k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashyap D, Tuli HS, Sharma AK. Ursolic acid (UA): a metabolite with promising therapeutic potential. Life Sciences. 2016;146:201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao N, Cheng S, Budhraja A, Gao Z, Chen J, Liu EH, Huang C, Chen D, Yang Z, Liu Q, Li P, Shi X, Zhang Z. Ursolic acid induces apoptosis in human leukaemia cells and exhibits anti-leukaemic activity in nude mice through the PKB pathway. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2012;165:1813–1826. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KH, Seo HS, Choi HS, Choi I, Shin YC, Ko SG. Induction of apoptotic cell death by ursolic acid through mitochondrial death pathway and extrinsic death receptor pathway in MDA-MB-231 cells. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2011;34:1363–1372. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0817-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Kong C, Zeng Y, Wang L, Li Z, Wang H, Xu C, Sun Y. Ursolic acid induces PC-3 cell apoptosis via activation of JNK and inhibition of Akt pathways in vitro. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2010;49:374–385. doi: 10.1002/mc.20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H-Y, Chung H-Y, Kim K-H, Lee J-J, Kim K-W. Induction of differentiation in the cultured F9 teratocarcinoma stem cells by triterpene acids. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 1994;120:513–518. doi: 10.1007/BF01221027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng L, Zhang R, Tang F, Li C, Xing Y-Y, Xi T. Ursolic acid induces U937 cells differentiation by PI3K/Akt pathway activation. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines. 2014;12:15–19. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(14)60003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang H-C, Huang C-Y, Lin-Shiau S-Y, Lin J-K. Ursolic acid inhibits IL-1p or TNF-a-induced C6 glioma invasion through suppressing the association ZIP/p62 with PKC-ζ and downregulating the MMP-9 expression. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2009;48:517–531. doi: 10.1002/mc.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang CY, Lin CY, Tsai CW, Yin MC. Inhibition of cell proliferation, invasion and migration by ursolic acid in human lung cancer cell lines. Toxicology In Vitro. 2011;25:1274–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin J, Chen Y, Wei L, Hong Z, Sferra TJ, Peng J. Ursolic acid inhibits colorectal cancer angiogenesis through suppression of multiple signaling pathways. International Journal of Oncology. 2013;43:1666–1674. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardenas C, Quesada AR, Medina MA. Effects of ursolic acid on different steps of the angiogenic process. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;320:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathak AK, Bhutani M, Nair AS, Ahn KS, Chakraborty A, Kadara H, Guha S, Sethi G, Aggarwal BB. Ursolic acid inhibits STAT3 activation pathway leading to suppression of proliferation and chemosensitization of human multiple myeloma cells. Molecular Cancer Research. 2007;5:943–955. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu YL, Kuo PL, Lin CC. Proliferative inhibition, cell-cycle dysregulation, and induction of apoptosis by ursolic acid in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Life Sciences. 2004;75:2303–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weng H, Tan ZJ, Hu YP, Shu YJ, Bao RF, Jiang L, Wu XS, Li ML, Ding Q, Wang XA, Xiang SS, Li HF, Cao Y, Tao F, Liu YB. Ursolic acid induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of gallbladder carcinoma cells. Cancer Cell International. 2014;14:96–106. doi: 10.1186/s12935-014-0096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H, Gao Y, Wang A, Zhou X, Zheng Y, Zhou J. Evolution in medicinal chemistry of ursolic acid derivatives as anticancer agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;92:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hua SX, Huang RZ, Ye MY, Pan YM, Yao GY, Zhang Y, Wang HS. Design, synthesis and in vitro evaluation of novel ursolic acid derivatives as potential anticancer agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;95:435–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Li Y, Jiang W, Ou M, Chen Y, Xu Y, Wu Q, Zheng Q, Wu F, Wang L, Zou W, Zhang YJ, Shao J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel ursolic acid derivatives as potential anticancer prodrugs. Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 2015;86:1397–1404. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]