Abstract

Background

Mild Behavioral Impairment (MBI) is a construct that describes the emergence at ≥ 50 years of age of sustained and impactful neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), as a precursor to cognitive decline and dementia. MBI describes NPS of any severity, which are not captured by traditional psychiatric nosology, persist for at least 6 months, and occur in advance of or in concert with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). While the detection and description of MBI has been operationalized in the International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment – Alzheimer’s Association (ISTAART-AA) research diagnostic criteria, there is no instrument that accurately reflects MBI as described.

Objective

To develop an instrument based on ISTAART-AA MBI criteria.

Methods

Eighteen subject matter experts participated in development using a modified Delphi process. An iterative process ensured items reflected the 5 MBI domains of 1) decreased motivation; 2) emotional dysregulation; 3) impulse dyscontrol; 4) social inappropriateness; and 5) abnormal perception or thought content. Instrument language was developed a priori to pertain to non-demented functionally independent older adults.

Results

We present the Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist (MBI-C), a 34-item instrument, which can easily be completed by a patient, close informant, or clinician.

Conclusion

The MBI-C provides the first measure specifically developed to assess the MBI construct as explicitly described in the criteria. Its utility lies in MBI case detection, and monitoring the emergence of MBI symptoms and domains over time. Studies are required to determine the prognostic value of MBI for dementia development, and for predicting different dementia subtypes.

Keywords: Dementia, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), Mild Behavioral Impairment (MBI), Preclinical dementia, Prodromal dementia, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms (NPS), Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)

Introduction

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) have been viewed as “non-cognitive” symptoms of dementia (also known as Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)). They include impairments of mood, anxiety, drive, perception, sleep, appetite, as well as behavioral disturbances such as agitation or aggression [1]. NPS have been described since Alois Alzheimer’s index case of Auguste D, who presented initially with emotional distress and delusions of infidelity, followed by cognitive impairment [2]. NPS are common in dementia with prevalence rates of up to 97%, increasing with time after diagnosis [3]. NPS are associated with faster cognitive decline and accelerated progression to severe dementia or death [4, 5], higher rates of institutionalization [6, 7], greater functional impairment [8], greater caregiver stress [9], worse quality of life [10], and higher burden of neuropathological markers of dementia [11]. NPS are often present at the time of dementia diagnosis [3], and for some they precede the onset of cognitive symptoms [12].

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in pre-dementia populations

A growing body of evidence describes NPS in older adults as early markers of cognitive decline and progression along the neurodegenerative spectrum. NPS are common in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and are associated with poorer cognitive and psychosocial function within MCI cohorts [13, 14]. Population-based [15, 16] as well as clinic-based cohort studies [17] provide consistent evidence that NPS in MCI are associated with higher risk for incident dementia, with an estimated annual rate of progression to dementia of 25% for MCI plus NPS [17] in contrast to the rate for MCI of 10 to 15 % per year [18]. Similarly, NPS in older adults with normal cognition confers a higher likelihood of progression to MCI and dementia, as shown in the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study [19], one Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center [20], the Danish Psychiatric and Somatic Health Register [21], the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging [22], the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study [23] and the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center database [24, 25].

The concept of “Mild Behavioral Impairment”

NPS are now recognized as core to the dementia process. The 2011 National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) consensus recommendations for diagnosis of all cause dementia include “changes in personality, behavior, or comportment— symptoms include: uncharacteristic mood fluctuations such as agitation, impaired motivation, initiative, apathy, loss of drive, social withdrawal, decreased interest in previous activities, loss of empathy, compulsive or obsessive behaviors, socially unacceptable behaviors”[26]. While behavioral symptoms are well-recognized early manifestations of Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) [27], they have been shown to appear early in Alzheimer’s and vascular dementias [28, 29]. It is not uncommon for patients with NPS who do not show obvious cognitive impairment to receive psychiatric diagnoses when the possibility of neurodegenerative disease has been overlooked [30]. This results in inappropriate, delayed, or suboptimal care [31].

The NPS Professional Interest Area (PIA) of the International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment (ISTAART), a subgroup of the Alzheimer’s Association (AA), operationalized the assessment of later life onset NPS as an “at-risk” state for cognitive decline and dementia. The ISTAART NPS PIA developed and published research diagnostic criteria for Mild Behavioral Impairment (MBI) [32] (Table 1). MBI describes later life onset of sustained and impactful NPS as symptoms of concern for cognitive decline and dementia. MBI symptoms, which can be mild, moderate or severe in intensity, are divided into the domains of 1) decreased motivation; 2) emotional dysregulation; 3) impulse dyscontrol; 4) social inappropriateness; and 5) abnormal perception or thought content. These domains are associated with well-characterized syndromes of cognitive decline. By definition, MBI is described in a population who does not have dementia, and it is precluded by a formal psychiatric diagnosis. The goals of developing the MBI criteria are 1) to assess psychiatric symptoms as markers of prodromal and preclinical stages of neurodegenerative disease, and 2) serve as a template for validation of the MBI construct from nosological, epidemiological, neurobiological, treatment, and dementia prevention perspectives.

Table 1.

ISTAART-AA MBI Criteria

|

Current rating scales

Given that MBI is a new construct, there is no validated rating scale for its assessment. The diagnosis and detection of NPS in pre-clinical populations has generally fallen under the realm of adult and geriatric psychiatry, with the aim of diagnosing other psychiatric syndromes. For dementia clinicians and researchers, the most commonly used rating scales for NPS are the informant-rated Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) [33], and the interview-based NPI [34, 35]. Other rating scales for NPS used in clinical trials include the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease (BEHAVE-AD) [36], the Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) [37], which was developed for nursing home use, and the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale (NBRS) [38]. However, as NPS were initially described in the context of dementia, often in institutionalized patients, many of the items in these rating scales are dementia-focused and not relevant to functionally independent community dwelling adults (eg. wandering, purposeless activity, fear of being alone, kicking, biting, grabbing, scratching, roaming, restlessness, pacing and resistiveness to care). Furthermore, these measures utilize reference times (2–4 weeks) that are much too short for the detection of a neurodegenerative disease prodrome. Given the transient nature of NPS [39], a longer observation of 6 months allows time for reactive states (arising from adversity, sleep deprivation, medications, for example) to pass, and for a fuller consideration of primary psychiatric illness. Hence there is need for a measure with a broad scope and sufficient reference time to detect and measure the MBI construct in patients who have no more than mild cognitive impairment.

Materials and Methods

Consistent with methods used in development of other NPS rating scales [35, 40], we implemented a modified Delphi process [41, 42], including 18 subject matter experts, to create an instrument based on MBI domains as described in the ISTAART-AA MBI criteria [32]. The aim was to create a comprehensive list of concise and relevant questions for NPS, and then narrow the number with successive iterations, to create a final version of the rating scale that could be feasibly implemented in clinical and community settings.

Delphi working group and expert panel

MBI-C development leaders (ZI and CGL) met in person in July 2015 to create the framework for development of the MBI-C and to assemble an expert panel. Most panel members were ISTAART NPS PIA members who had expressed interest in rating scale development. Additional panel members were approached and added thereafter based on expertise. Ultimately, a panel of 18 members was formed including 15 MDs with clinical and research expertise in NPS (representing psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, neuropsychiatry, behavioural neurology, and cognitive neurology), as well as 4 PhDs (one of which was also an MD) with expertise in psychology, psychopharmacology, rating scale development, and clinical trials. Panel members represented 4 countries in 3 continents and 13 institutions.

Outline of Delphi process

The initial goal of the Delphi process was to generate a list of items that may be relevant to the identification of NPS in a non-demented population. The clinician-rated NPI-C [35], an expanded version of the NPI, was used as a starting point with items re-categorized into MBI domains described in the consensus definition. At first pass, some questions were omitted that were judged relevant to later stages of dementia and less applicable to MBI. Additional questions were included ad hoc through the Delphi iterations (below). A list of 88 items was generated for the next steps.

Delphi iterative rounds

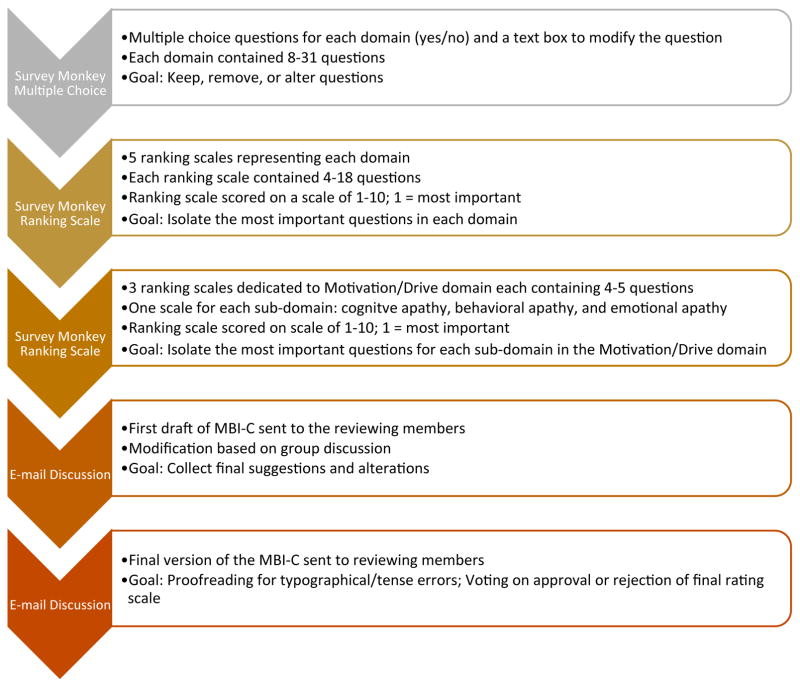

The 88 items were sent to the members of panel via an online survey through www.surveymonkey.com. This allowed members of the group to select whether each question did or did not belong to a particular MBI domain, with an optional response box to modify the question and/or choose a different domain. After analysis of the responses, questions were removed, shifted to a different MBI domain, or reworded; further, new questions were solicited from panel members and added.

Following those changes, a second survey was created. The panel was asked to rank each question in order of decreasing importance. The questions deemed least important by the majority were excluded reducing the number of questions to be included in the MBI-C. A final survey was sent to the reviewing group where each member was, again, asked to rank the questions in each domain from most to least important. The a priori target was a relatively short instrument consisting of about 30 to 40 items.

From the responses to the 3rd Delphi round, a draft of the MBI-C was created and sent to the panel via email for additional comments and feedback. Extensive email discussions resulted in modifications to organization, wording, complexity of language, verb tense and gender. A final version of the MBI-C was created and sent to all members for voting on final approval.

The flow of the modified Delphi-process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Modified Delphi-process flow diagram for MBI-C development

Results

Structure of the MBI-C

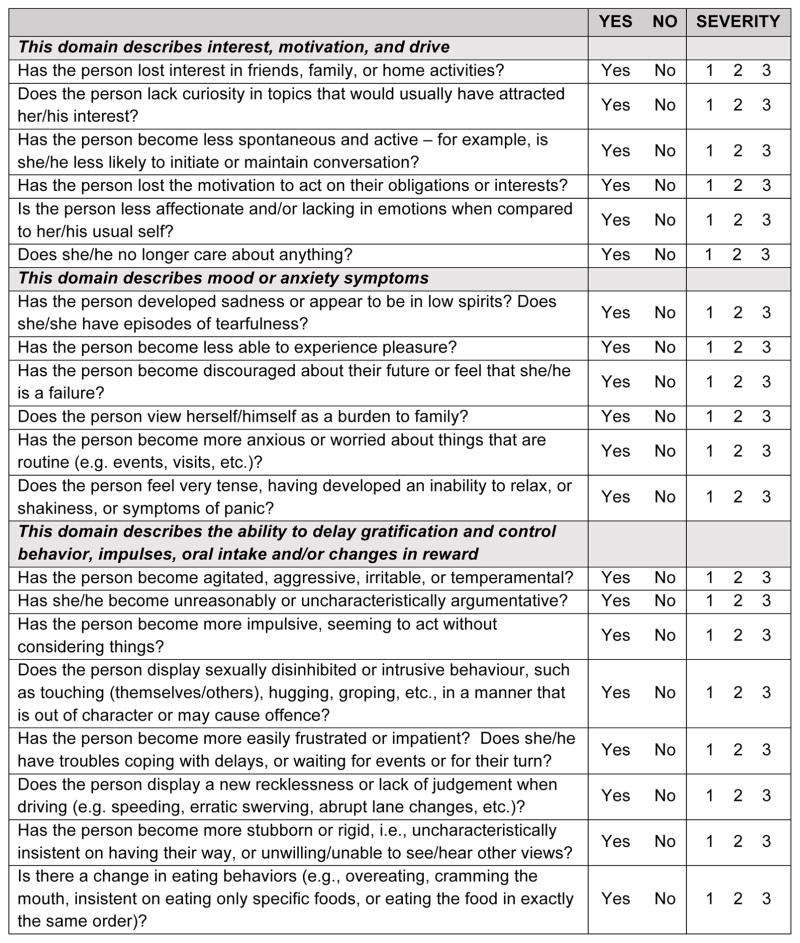

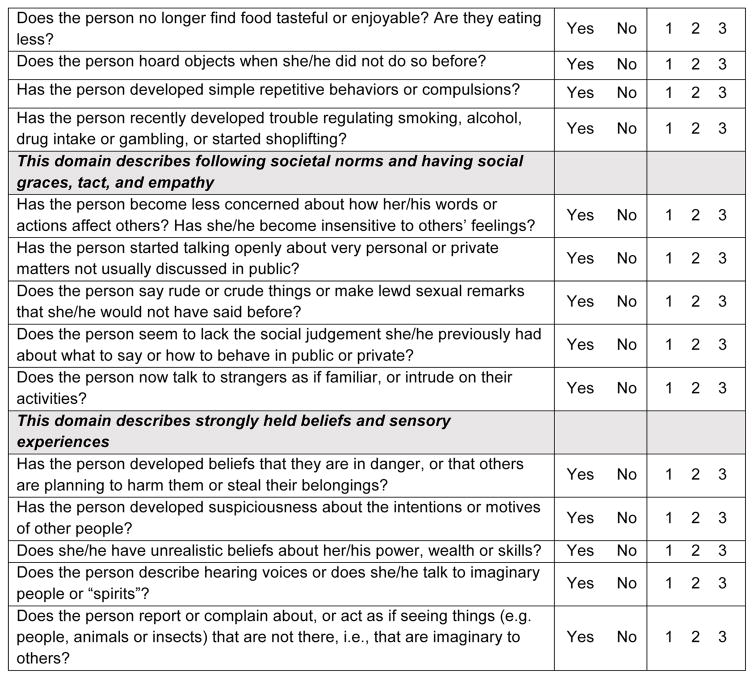

The MBI-C was structured to be consistent with the 5 domains in the MBI criteria [32]: decreased motivation, emotional dysregulation, impulse dyscontrol, social inappropriateness, and abnormal perception or thought content. In order to translate domain names to descriptions that caregivers or family members could understand when completing the rating scale, domain explanations were provided in the headers of each section. By consensus, decreased motivation was described as a loss of “interest, motivation and drive”. Emotional dysregulation was described as “mood or anxiety symptoms”. Impulse dyscontrol was described as a loss of “the ability to delay gratification and control behavior, impulses, oral intake and/or changes in reward”. Social inappropriateness was described as “not following societal norms and/or lack of social graces, tact or empathy”. Abnormal perception or thought content was described as developing “strongly held beliefs and sensory experiences.” Each domain was populated by relevant questions, which were also moved and/or modified through the Delphi process, prior to each question being subject to a vote.

Scoring of the MBI-C

A simple scoring system was used, specifically an endorsement of “yes” or “no” for each item followed by a severity rating of 1-mild, 2-moderate, or 3-severe [33]. The rationale for assessing only symptom severity was based on the finding that symptom severity is more strongly correlated with caregiver distress than symptom frequency [43]. The MBI-C was designed to generate an overall score, as well as domain scores for later validation and prognostication.

Duration and rater specifiers

Core to the construct of MBI is symptom persistence for at least 6 months, and that symptoms are an impactful change from baseline behaviors. Thus, the initial descriptor was agreed upon as follows: select “Yes” only if the behavior has been present for at least 6 months (continuously, or on and off) and is a change from her/his longstanding pattern of behavior. Otherwise, select “No”. Tick boxes were generated for clinician, informant, or subject rater identification, as well as for clinical or research use.

Final version of the MBI-C

The MBI-C (Figure 2) is a 2-page questionnaire consisting of 34 items, in 5 domains. The apathy domain consists of 6 questions including assessments of cognitive, behavioral and emotional apathy. The affect domain contains 6 items, including 4 for depressive features of low mood, anhedonia, hopelessness and guilt, and 1 question each for worry and panic. The impulse dyscontrol domain is the largest, with 12 questions describing agitation, aggression, impulsivity, recklessness, and abnormal reward and reinforcement. The social appropriateness domain consists of 5 questions assessing sensitivity, empathy and tact. Finally, the abnormal thought and perception domain consists of 5 questions assessing suspiciousness, grandiosity, and auditory and visual hallucinations.

Figure 2.

MBI Checklist

Discussion

The MBI-C was created as a tool, to be used primarily by family members and close informants, to better describe and measure behavioral changes exhibited by older adults that might precede the onset of dementia. It was specifically designed to: 1) operationalize the MBI concept; 2) measure a selected list of NPS which may help identify prodromal or preclinical disease; and 3) help predict risk of several dementias, including, but not exclusive to AD. Hence, the explicit goal of the MBI-C is case detection, specifically the diagnosis of a behavioural pre-dementia “at-risk” state. The measure is intended for use in both clinical and research settings in order to detect such NPS, and measure changes in those NPS over time.

The MBI-C will serve multiple functions as knowledge emerges on the role of later life onset NPS as a risk of cognitive decline and neurodegeneration. It will help estimate MBI prevalence. Greater awareness of neuropsychiatric precursors to dementia is needed in the clinical setting and in treatment research. This awareness must be informed by reliable prevalence estimates based on structured diagnostic criteria and rating scales. The systematic description and measurement of late life NPS meets an important unmet need in dementia care, which is early identification of dementia and the at-risk population. Given the symptom duration requirement of 6 months, it is difficult to extrapolate prevalence of the MBI preclinical phenotype from current studies, which have generally required one month of symptoms. The MBI-C may serve as a standard assessment in community and clinical samples to provide symptom and syndrome estimates that are unavailable with current instruments.

In addition to potentially prognosticating dementia, the MBI-C may identify target substrates (symptoms and domains) for non-pharmacological and pharmacological intervention, and neurobiological research. By and large, disease modifying agents have been unsuccessful in improving dementia outcomes, in part due to poor recruitment and retention in the early phase of illness, and high biomarker screen failure rates [44]. Given the strong evidence that later life emergence of NPS is related to dementia risk, the MBI-C could be useful for early case detection, biomarker screening, and clinical trial enrolment. MBI groups can also be studied for response to non-pharmacological interventions like diet, exercise, cognitive training and social activity, in order to alter cognitive and neurodegenerative outcomes, as these interventions may also be more effective earlier on in the neurodegenerative disease course.

MBI is a departure from traditional ways of appreciating NPS, and the MBI-C is tailored for pre-dementia populations. Symptoms are described for their appearance in pre-dementia states and not for presentations associated with established dementia, and the 6-month requirement in the MBI criteria reflects the need to discount transient reactions. Therefore, there is no clear comparator scale. Reliability, validity, and utility of the MBI-C need to be determined in subsequent studies. Prevalence studies using the MBI-C and comparisons of results with data from formal clinical assessments are necessary. The impact on NPS prevalence of different reference times (such as one month versus 6 months) should be studied. Reliability needs to be assessed in community and clinical samples, in those with normal cognition or subjective cognitive decline and MBI, and those with MCI and MBI. Scoring has yet to be validated. It is not yet clear whether total scores predict incident cognitive decline or dementia, if there is an optimal cutoff score for prognostication, and if there are differences in risk based on the various aggregate domain scores. Additionally, the prognostic value of various domain scores on subtype of dementia is to be determined. Validation is required against clinical diagnosis, versus current instruments, and for content and criterion validity.

Further, while the MBI-C is primarily intended to be given to a family member or close informants, its utility when rated by a clinician or when self-rated need to be determined. Future iterations of MBI-C will explore a clinician rated version, similar to the NPI-C, to determine if a combination of clinician and informant information can increase the prognostic power of the diagnosis. Whether NPS emerge in advance of MCI, concurrent with MCI or after MCI is worthy of study, to determine if natural history of MBI reflects different neurobiology and functional/cognitive outcomes. Finally, while designed in an English-speaking population, the MBI-C needs to be translated, by culturally and linguistically sensitive translators, into other languages for validation and study in non English-speaking countries, and for patients and family members who do not speak English fluently.

Conclusion

NPS occur in dementia and other neurological disorders, are more common in Mild Cognitive Impairment than in age matched controls with normal cognition [45], and can be confused with primary psychiatric disorders such as depression and mania. Current nosology does not offer a systematic way of defining and measuring later-life onset, persistent and impactful NPS, which may be the harbinger of neurodegenerative disorders. Well-defined operational criteria will enable researchers to assess the heuristic value of identifying an MBI population, who are at greater risk for cognitive decline and dementia, and assist clinicians in diagnosis.

We present the MBI-C, a rating scale developed by a modified Delphi process, including panel members expert in neuropsychiatric symptoms in clinical and pre-clinical populations. The instrument was purposely developed to reflect the new ISTAART-AA MBI criteria, and has potential utility in describing and measuring change in later-life onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms that may precede the onset of dementia. The MBI-C is a starting point for further study into the impact of later life onset NPS and risk of cognitive and dementia. The MBI-C now allows measurement of MBI prevalence, and determination of the risk of cognitive decline and dementia, based on overall and domain scores.

Acknowledgments

ZI is supported by the Hotchkiss Brain Institute via the Alzheimer Society of Calgary

EES is supported by the Katthy Taylor Chair in Vascular Dementia and CIHR

DS is supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs

GS is supported by National Institute of Health: AG038893 and AG041633

JC acknowledges funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant: P20GM109025) and support from Keep Memory Alive.

MEM is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Australian Research Council (ARC) Dementia Research Development Fellowship #1102028.

SG is supported by CIHR and the Weston Brain Institute

KGL is supported in part by NIH grant P50AG005146 for the Johns Hopkins ADRC.

Footnotes

All authors have contributed to the work, agree with the presented findings, and that the work has not been published before nor is being considered for publication in another journal.

No authors declare any conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Ballard C, Day S, Sharp S, Wing G, Sorensen S. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: importance and treatment considerations. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:396–404. doi: 10.1080/09540260802099968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, Miller DS, Smith GS, Bell J, Evans J, Lee M, Porsteinsson A, Lanctôt KL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P, Lyketsos CG, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Norton MC, Breitner J, Steffens DC, Tschanz JT. Point and 5-year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern Y, Albert M, Brandt J, Jacobs D, Tang M, Marder K, Bell K, Sano M, Devanand D, Bylsma F. Utility of extrapyramidal signs and psychosis as predictors of cognitive and functional decline, nursing home admission, and death in Alzheimer’s disease Prospective analyses from the Predictors Study. Neurology. 1994;44:2300–2300. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters ME, Schwartz S, Han D, Rabins PV, Steinberg M, Tschanz J, Lyketsos C. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as predictors of progression to severe alzheimer’s dementia and death: the Cache Country dementia progression study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:460–465. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14040480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiener PK, Kiosses DN, Klimstra S, Murphy C, Alexopoulos GS. A short-term inpatient program for agitated demented nursing home residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:866–872. doi: 10.1002/gps.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balestreri L, Grossberg A, Grossberg GT. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia as a risk factor for nursing home placement. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer CE, Ismail Z, Schweizer TA. Delusions increase functional impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cog Dis. 2012;33:393–399. doi: 10.1159/000339954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer CE, Ismail Z, Schweizer TA. Impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2012;2:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karttunen K, Karppi P, Hiltunen A, Vanhanen M, Välimäki T, Martikainen J, Valtonen H, Sivenius J, Soininen H, Hartikainen S. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in patients with very mild and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:473–482. doi: 10.1002/gps.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zubenko GS, Moossy J, Martinez AJ, Rao G, Claassen D, Rosen J, Kopp U. Neuropathologic and neurochemical correlates of psychosis in primary dementia. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:619–624. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530180075020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devineni B, Onyike CU. Young-onset dementia epidemiology applied to neuropsychiatry practice. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2015;38:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman H, Scheltens P, Scarpini E, Hermann N, Mesenbrink P, Mancione L, Tekin S, Lane R, Ferris S. Behavioral symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2004;62:1199–1201. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118301.92105.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ismail Z, Elbayoumi H, Smith EE, Fischer CE, Schweizer TA, Millikin C, Hogan DB, Patten SB, Fiest KM. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for the Prevalence of Depression in Mild Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters M, Rosenberg P, Steinberg M, Norton M, Welsh-Bohmer K, Hayden K, Breitner J, Tschanz J, Lyketsos C. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as risk factors for progression from CIND to dementia: the Cache County Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:1116–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pink A, Stokin GB, Bartley MM, Roberts RO, Sochor O, Machulda MM, Krell-Roesch J, Knopman DS, Acosta JI, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Mielke MM, Petersen RC, Geda YE. Neuropsychiatric symptoms, APOE epsilon4, and the risk of incident dementia: a population-based study. Neurology. 2015;84:935–943. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Appleby BS, Oh ES, Geda YE, Lyketsos CG. The association of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI with incident dementia and Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1133–1142. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banks SJ, Raman R, He F, Salmon DP, Ferris S, Aisen P, Cummings J. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Prevention Instrument Project: Longitudinal Outcome of Behavioral Measures as Predictors of Cognitive Decline. Dement Geriatr Cog Dis Extra. 2014;4:509–516. doi: 10.1159/000357775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, Zoller AS, Rudel RK, Gomez-Isla T, Blacker D, Hyman BT, Locascio JJ, Johnson KA, Sperling RA. Subjective Cognitive Concerns and Neuropsychiatric Predictors of Progression to the Early Clinical Stages of Alzheimer Disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:1642–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kørner A, Lopez AG, Lauritzen L, Andersen PK, Kessing LV. Acute and transient psychosis in old age and the subsequent risk of dementia: A nationwide register-based study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2009;9:62–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geda YE, Roberts RO, Mielke MM, Knopman DS, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Sochor O, Tangalos EG, Petersen RC. Baseline Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and the Risk of Incident Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Population-Based Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:572–581. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13060821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Köhler S, Allardyce J, Verhey FR, McKeith IG, Matthews F, Brayne C, Savva GM. Cognitive decline and dementia risk in older adults with psychotic symptoms: a prospective cohort study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masters MC, Morris JC, Roe CM. “Noncognitive” symptoms of early Alzheimer disease A longitudinal analysis. Neurology. 2015;84:1–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leoutsakos J-MS, Forrester SN, Lyketsos C, Smith GS. Latent classes of neuropsychiatric symptoms in NACC controls and conversion to mild cognitive impairment or dementia. J Alzheimes Dis. 2015;48:483–493. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W, Miller BL, Kramer JH, Rankin K, Wyss-Coray C, Gearhart R, Phengrasamy L, Weiner M, Rosen HJ. Behavioral disorders in the frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2004;62:742–748. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113729.77161.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taragano F, Allegri R. The Eleventh International Congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association.2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taragano FE, Allegri RF, Krupitzki H, Sarasola D, Serrano C, Lyketsos C. Mild behavioral impairment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:584–592. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolley JD, Khan BK, Murthy NK, Miller BL, Rankin KP. The diagnostic challenge of psychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative disease: rates of and risk factors for prior psychiatric diagnosis in patients with early neurodegenerative disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:126–133. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06382oli. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jalal H, Ganesh A, Lau R, Lysack J, Ismail Z. Cholinesterase-inhibitor Associated Mania: A Case Report and Literature Review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41:278–280. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100016735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ismail Z, Smith EE, Geda Y, Sultzer D, Brodaty H, Smith G, Agüera-Ortiz L, Sweet R, Miller D, Lyketsos CG. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, Lopez OL, DeKosky ST. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48:10S–16S. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.10s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Medeiros K, Robert P, Gauthier S, Stella F, Politis A, Leoutsakos J, Taragano F, Kremer J, Brugnolo A, Porsteinsson A. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Clinician rating scale (NPI-C): reliability and validity of a revised assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:984–994. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reisberg B, Auer SR, Monteiro IM. Behavioral pathology in Alzheimer’s disease (BEHAVE-AD) rating scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;8:301–308. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199911001-00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller RJ, Snowdon J, Vaughan R. The use of the Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory in the assessment of behavioral disorders in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:546–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sultzer DL, Levin HS, Mahler ME, High WM, Cummings JL. Assessment of cognitive, psychiatric, and behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia: the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:549–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergh S. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia in Norwegian nursing homes: the course of the symptoms and the effect of discontinuation of psychotropic medication. University of Oslo; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2308. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. American journal of public health. 1984;74:979–983. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.9.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milholland AV, Wheeler SG, Heieck JJ. Medical assessment by a Delphi group opinion technic. New Eng J Med. 1973;288:1272–1275. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197306142882405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, Bray T, Castellon S, Masterman D, MacMillan A, Ketchel P, DeKosky ST. Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gauthier S, Albert M, Fox N, Goedert M, Kivipelto M, Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Middleton LT. Why has therapy development for dementia failed in the last two decades? Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geda YE, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Smith GE, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and normal cognitive aging: population-based study. Arc Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1193–1198. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]