Abstract

Trichotillomania can be associated with the formation of trichobezoars (hair ball) usually located in the stomach. Trichobezoars may lead to complications including bowel obstruction, and perforation. Patients with a history of diabetes, certain psychiatric disorders, prior gastric surgery and poor mastication ability are at an increased risk of developing bezoars. We are presenting a case of patient who suffered from a large, recurrent trichobezoar, who had a history of gastric bypass surgery as well as trichotillophagia. The endoscopic method used to remove the large bezoar will also be discussed. We have reviewed the cases published, in which patients developed bezoars after undergoing gastric bypass surgery. The purpose of this study is to raise awareness among clinicians that patients with certain psychiatric issues who had prior gastric surgeries, are at eminent risk of bezoar formation. A multidisciplinary approach including cognitive behavioural therapy, dietary education and pharmacotherapy should be taken to prevent complications.

Keywords: endoscopy, eating disorders, Gastrointestinal Surgery, stomach and duodenum

Background

Trichotillomania is an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder characterised by the strong urge to pull out one’s own hair. The prevalence among adults is 0.6%–3.6%. Some individuals discard the hair, while others may play with them, and some even ingest the hair (trichotillophagia). An indigested mass of hair found in the gastrointestinal system is known as a trichobezoar.1 Trichobezoars (hair ball) are usually located in the stomach, but may extend through the pylorus into the duodenum and small bowel (Rapunzel syndrome). The bezoars can lead to complications including bowel obstruction and/or perforation, pancreatitis and cholangitis.2 3

Gastric bezoars can occur after undergoing gastric surgery. A Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is one of the most common types performed in the treatment of morbid obesity because of its acceptable early and late adverse effects.4 There are very few documented cases of patients developing bezoars after this procedure. However, the association between bezoar formation, abnormal eating habits and prior gastric bypass surgery is not completely understood.5

We are presenting a case of recurrent trichobezoar in a patient who had prior Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, as well as a history of trichotillophagia successfully removed endoscopically.

Case presentation

A female aged 37 years with a past medical history of asthma and iron deficiency anaemia, as well as a surgical history significant for gastric bypass surgery (10 years prior) and gastric outlet obstruction secondary to impacted bezoar (requiring endoscopic removal), presented with the chief complaint of abdominal pain for 3 days. The pain was severe in nature with radiation to the back. It was also associated with a loss of appetite, sensation of abdominal fullness as well as nausea with postprandial vomiting.

On examination, vital signs were stable and patient afebrile. Abdominal exam was positive for mild epigastric tenderness, but otherwise soft, with normal bowel sounds. Neurological, cardiovascular and respiratory exams were unremarkable.

The patient stated that she had stopped the practice of eating her own hair, since suffering the prior gastric obstruction. However, on further questioning, she admitted to having recently fallen back into the same habit.

Investigations

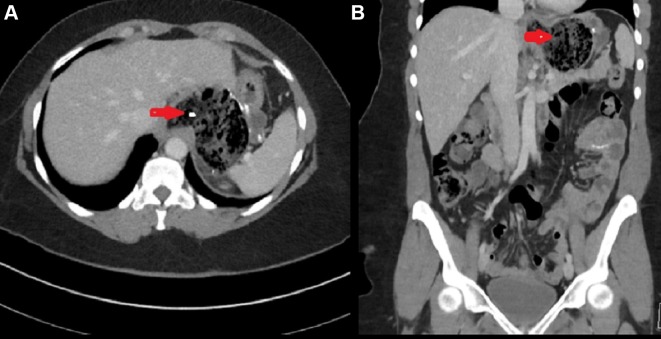

Labs revealed her haemoglobin level to be 8.5 g/dL with a haematocrit of 28%. White blood cell count was 11 000/µL. Renal, hepatic function tests and lipase were all within normal limits, and electrolytes without abnormalities. CT abdomen/pelvis was obtained, which revealed the presence of a trichobezoar in the stomach (figure 1A,B).

Figure 1 (A).

CT scan of abdomen axial view showing stomach distension with intraluminal heterogeneous mass with air trapped in the mass. (B) CT scan of abdomen coronal view showing intraluminal mass with interspersed gas in stomach (red arrow).

Differential diagnosis

Initial presentation included many possible aetiologies for her abdominal pain, including peptic ulcer disease, acute pancreatitis, hepatitis, gastritis and perforated viscus in the setting of her prior Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.

Based on the previous history of trichobezoars with prior gastric surgery, recurrent bezoar formation was a high differential diagnosis. CT abdomen was obtained, which confirmed the presence of a large intraluminal mass covering almost the whole body of stomach (figure 1A,B).

Treatment

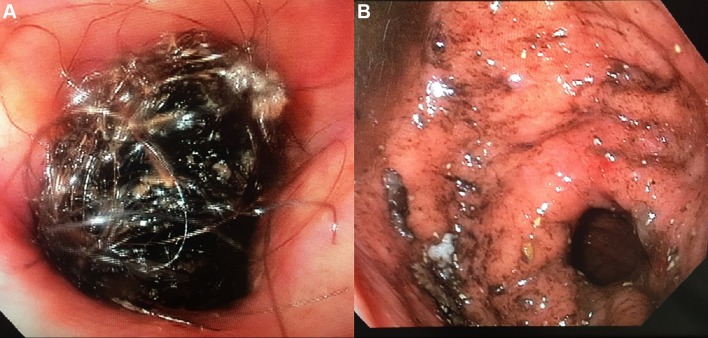

The patient was kept without oral food or liquids, and started on intravenous hydration and pantoprazole. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed. During the procedure, the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction were unremarkable, and gastrojejunostomy anastomosis was intact. A large bezoar consisting of hair mixed with food particles was found in the gastric pouch (figure 2A). Initial attempts at removal using a Roth net and Tri-Prong forceps were unsuccessful. The bezoar was bulky, and unable to cross the upper oesophageal sphincter. During the procedure, the patient began to desaturate, and was subsequently intubated for impending respiratory failure.

Figure 2 (A).

Endoscopy showing large hair mass obstructing the lumen. (B) Underlying mucosa of stomach after removal of bezoar

The procedure was resumed after intubation. The bezoar was broken into smaller pieces with endoscopic scissors and removed in a piecemeal fashion using Rat Tooth forceps, Tri-Prong forceps and a Roth net. During the procedure, a plastic round clip was discovered within the bezoar, which was the likely culprit for the difficult extraction across the gastro-oesophageal junction. The clip was removed with Rat Tooth forceps and the remainder of the bezoar was cleared easily (figure 3). The underlying mucosa of the oesophagus and gastric pouch was undamaged (figure 2B).

Figure 3.

Trichobezoar removed with plastic clip (red arrow).

Outcome and follow-up

Post procedure, the patient was successfully extubated and started on a liquid diet, which was slowly advanced as tolerated. Psychiatry was consulted for counselling for chronic trichotillophagia and the patient was later discharged with continued outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Discussion

Bezoar is derived from the Arabic word ‘bazahr’, meaning antidote. Bezoars are an uncommon cause of gastric and/or intestinal obstruction, often secondary to ingestion of indigestible materials.6 The condition is subdivided into trichobezoars (caused by hair ingestion), disopyrobezoars (caused by ingestion of persimmon fruit), phytobezoars (caused by vegetables) and pharmacobezoars (caused by the use of medicinal preparations).6 7 Gypsum plaster (also known as plaster of Paris) is a non-toxic substance that has been associated with acute bezoar formation after ingestion. One such reported case involves a young female who ingested a significant quantity of the plaster in an attempt at suicide, and subsequently developed gastric outlet obstruction.8 Risk factors for development of bezoars include aberrant dietary behaviour (ie, consuming inedible material), impaired mastication, prior history of gastric surgery, diabetic gastroparesis as well as altered gastric physiology including but not limited to decreased acid production and impaired gastric emptying. Trichobezoars are most commonly found in the stomach followed by small intestine, colon and rectum. Rapunzel syndrome is a name for the condition when trichobezoar cross the pylorus into duodenum, jejunum, ileum and even colon.2 9 The name Rapunzel is taken from the classic German fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm, about a young girl with incredibly long hair. In most cases, trichotillomania accompanies comorbid psychological conditions such as anxiety, mood disorders, major depressive disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder.1

There is a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders among the candidates of bariatric surgery including depression, anxiety and binge eating disorders (BED).10 Wadden et al study showed that in patients with BED who had undergone bariatric surgery, weight loss and cerebrovascular disease risk improvement are comparable to those without BED. Also, greater weight reduction was noticed as compared with lifestyle modifications alone.11 There are no studies available regarding the outcome of bariatric surgery in patients with trichotillophagia. Future research is needed to identify the behavioural disorders in which gastric bypass surgery is contraindicated.

Common presenting symptoms includes abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting.12 The stomach is usually able to clear foreign bodies, thus it may take years to develop bezoars, especially one that is symptomatic.13 Our patient had two major risk factors for the development of a bezoar: a history of gastric bypass surgery and a predilection for consuming her own hair. Patients who have had gastrectomies are at higher risk of developing bezoar because these patients often suffer from gastric motility disorders, achlorhydria and loss of pyloric function.14 Our case is unique because this patient ingested a clip along with her hair, which may have been a nidus for the development of the trichobezoar.

There is a handful of published cases describing patients who developed bezoars after gastric surgery. Among them, majority are females and usually in their 50s. In most cases, phytobezoars developed with the diabetes mellitus being the most common associated risk factor, other risk factors include peptic ulcer disease and obesity.4 15 16 Kang et al presented a case where patient developed bezoar secondary to food glued in surgical nylon loop.17 Bowel obstruction is the most common complication, there is a case report where patient developed small bowel perforation.18 The interval for symptomatic bezoar formation among these cases ranged from 1 day (blood bezoar) to 7 years (phytobezoar) postgastric surgery.5 19 Some of these cases required laparotomy to remove the bezoar.19–21

Diagnosis was confirmed with barium studies, CT scan and upper endoscopy. CT scan revealed an intraluminal mass of variable density. Upper endoscopy was found to be the most sensitive test for diagnosis of bezoar, as well any other underlying pathology.8 22 Most of the gastric bezoars were removed endoscopically via fragmentation via water jet, suctioning and snares. Acetyl cysteine, hydrogen peroxide and Coca-Cola, cellulase have also been shown to be effective in the dissolution of these bezoars. In a few cases, the bezoars were treated with extracorporeal lithotripsy and the use of Nd-YAG lasers. In cases where conservative therapy fails (ie, hydration, chemical dissolution and use of prokinetic agents), bezoars should be removed endoscopically or surgically, if need arises.23 Our case is unique, as endoscopic scissors were used to fragment the large trichobezoar prior to successful endoscopic retrieval.

Bezoars recur in approximately 14% of patients. Clinical focus must be placed on prevention and the treatment of underlying risk factors. High-risk patients should be educated regarding proper chewing techniques as well counselled to avoid high fibre diets. Psychiatric evaluation should also be obtained to address troublesome eating habits, and underlying psychiatric conditions.8 23 Treatment of trichotillomania may include both non-pharmacotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Habit reversal techniques and stimulus control training are effective psychological therapies. Pharmacotherapy can include the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, clomipramine, N-acetylcysteine and olanzapine.24–26 Bariatric surgery cases with eating disorders including trichotillophagia may benefit from behavioural therapy preoperatively and postoperatively. The optimal timing of such adjunctive intervention needs to be determined.

Learning points.

Patients with compulsive eating disorders are at higher risk of developing bezoars, especially those who have had prior gastric surgery.

Large trichobezoars can be removed endoscopically via fragmentation with the aid of endoscopic scissors, which may reduce the need for more invasive surgical interventions.

Psychiatric evaluation with pharmacological/behavioural therapy can reduce recurrent bowel obstruction in patients with a history of trichotillophagia.

Eating disorders are not considered as the contraindication to the bariatric surgery. Future research is required to identify the behavioural disorders in which bariatric surgery should be deferred based on the outcome.

Footnotes

Contributors: SI gave the idea and framework. WA and GU wrote the manuscript and AH read the manuscript and gave the inputs.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Woods DW, Houghton DC. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of trichotillomania. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2014;37:301–17. 10.1016/j.psc.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorter RR, Kneepkens CMF, Mattens E, et al. Management of trichobezoar: case report and literature review. Pediatric Surgery International. Berlin/Heidelberg 2010;26:457–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shawis RN, Doig CM. Gastric trichobezoar associated with transient pancreatitis. Arch Dis Child 1984;59:994–5. 10.1136/adc.59.10.994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ertugrul I, Tardum Tardu A, Tolan K, et al. Gastric bezoar after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;23:112–5. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabaac BJ, Tabaac V. Pica patient, status post gastric bypass, improves with change in medication regimen. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2015;5:38–42. 10.1177/2045125314561221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaka M, Ehirchiou A, Alkandry TT, et al. Huge plastic bezoar: a rare cause of gastrointestinal obstruction. Pan Afr Med J 2015;21 10.11604/pamj.2015.21.286.7169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas JD, Spivak AM, perfect storm A. Gastric bezoar. Am J Med 2009;122:519–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yegane RA, Bashashati M, Bashtar R, et al. Gastrointestinal obstruction due to plaster ingestion: a case-report. BMC Surg 2006;6:4 10.1186/1471-2482-6-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhakal OP, Dhakal M, Bhandari D. Phytobezoar leading to gastric outlet obstruction in a patient with diabetes. BMJ Case Rep 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yen YC, Huang CK, Tai CM. Psychiatric aspects of bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2014;27:374–9. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadden TA, Faulconbridge LF, Jones-Corneille LR, et al. Binge eating disorder and the outcome of bariatric surgery at one year: a prospective, observational study. Obesity 2011;19:1220–8. 10.1038/oby.2010.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasri B, Calin M, Shah A, et al. A rare cause of small bowel obstruction due to bezoar in a virgin abdomen. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;19:144–6. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.12.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousfiha N, Derieux S, Amiot A, et al. Upper gastrointestinal obstruction due to trichobezoar. Presse Med 2014;43:1008–9. 10.1016/j.lpm.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Porat T, Sherf Dagan S, Goldenshluger A, et al. Gastrointestinal phytobezoar following bariatric surgery: systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016;12:1747–54. 10.1016/j.soard.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto D, Carrodeguas L, Soto F, et al. Gastric bezoar after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2006;16:365–8. 10.1381/096089206776116561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ionescu AM, Rogers AM, Pauli EM, et al. An unusual suspect: coconut bezoar after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2008;18:756–8. 10.1007/s11695-007-9343-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang HS, Hyun JJ, Kim SY, et al. Bezoar formation and obstruction caused by a surgical nylon thread after gastric bypass surgery. Endoscopy 2013;45:E412 10.1055/s-0033-1344991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sammut SJ, Majid S, Shoab S. Phytobezoar: a rare cause of late upper gastrointestinal perforation following gastric bypass surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2012;94:e85–e87. 10.1308/003588412X13171221588938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pazouki A, Pakaneh M, Khalaj A, et al. Blood bezoar causing obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5:183–5. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung E, Barnes R, Wong L. Bezoar in gastro-jejunostomy presenting with symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2008;2:323 10.1186/1752-1947-2-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deront Bourdin F, Iannelli A, Delotte J. Phytobezoar: an unexpected cause of bowel obstruction in a pregnant woman with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:e49–e51. 10.1016/j.soard.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guner A, Kahraman I, Aktas A, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction due to duodenal bezoar: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2012;3:523–5. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zin T, Maw M, Pai DR, et al. Efferent limb of gastrojejunostomy obstruction by a whole okra phytobezoar: Case report and brief review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012;4:197–200. 10.4253/wjge.v4.i5.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dougherty DD, Loh R, Jenike MA, et al. Single modality versus dual modality treatment for trichotillomania: sertraline, behavioral therapy, or both? J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1086–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris SH, Zickgraf HF, Dingfelder HE, et al. Habit reversal training in trichotillomania: guide for the clinician. Expert Rev Neurother 2013;13:1069–77. 10.1586/14737175.2013.827477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franklin ME, Zagrabbe K, Benavides KL. Trichotillomania and its treatment: a review and recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother 2011;11:1165–74. 10.1586/ern.11.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]