Abstract

Bacillus cereus is a Gram-positive spore-forming rod widely found in the environment and is thought to be a frequent source of contamination. This micro-organism is reportedly a significant pathogenic agent among immunocompromised individuals. Furthermore, multiple cases of fulminant septicaemia have been reported among individuals receiving chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukaemia. In some cases, B. cereus septicaemia was associated with multiple haemorrhages. We, herein, describe a patient with an extremely acute course of B. cereus septicaemia characterised by haemorrhage and infarction of multiple organs, which led to his death. Our findings suggest that delayed treatment of B. cereus in patients with haematologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy may result in extremely poor outcomes; thus, immediate empirical treatment with vancomycin should be considered.

Keywords: stroke, infectious diseases, haematology (incl blood transfusion)

Background

Bacillus cereus is a widespread Gram-positive spore-forming rod frequently considered a contaminant of bacterial cultures. According to previous studies, this organism is a significant pathogenic agent in infants, intravenous drug users, patients with malignancy and immunocompromised individuals.1 In particular, fulminant septicaemia has been reported in patients receiving chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukaemia. Intracranial haemorrhage associated with B. cereus septicaemia has also been reported.2–7 We, herein, describe a patient with an extremely acute course of B. cereus septicaemia that led to his death. The autopsy revealed that the septicaemia was accompanied by intracranial haemorrhage and kidney infarction.

Case presentation

An elderly man with a history of acute myelogenous leukaemia presented to our emergency department with a 1-day history of chills and multiple arthralgia. Before presentation, he had been asymptomatic and feeling well until the onset of chills and pain. He denied headache, chest pain, dyspnoea, abdominal pain and lumbar pain. He had a medical history of psoriasis vulgaris 30 years earlier and bilateral optic neuritis 50 years earlier. Two years earlier, he had been diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukaemia and was currently receiving treatment with azacitidine. The 16th azacitidine course was completed 2 weeks before the present admission. He was taking no daily medications and did not smoke or consume alcohol. His family history was irrelevant. On admission, his body temperature was 39.2°C; blood pressure, 130/54 mm Hg; pulse rate, 101 beats/min; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 99% on room air. Additionally, a bounding pulse was noted (measured at the upper extremity). The physical examination revealed no significant findings with the exception of conjunctival pallor. Laboratory examination showed a white cell count of 0.2 x 109/L (reference range, 3.3–8.6 x 109/L), neutrophil count of 0.03 x 109/L, haemoglobin level of 6.7 g/dL (reference range, 13.5–16.9 g/dL), platelet count of 2 x 109/L (reference range, 158–353 x 109/L) and C reactive protein level of 9.9 mg/L (reference range, 0.00–0.15 mg/L). His coagulation profile showed a prothrombin time-international normalised ratio (PT-INR) of 1.06, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of 26.0 s (reference range, 25.0–35.0 s), fibrinogen level of 299 mg/dL (reference range, 220–410 mg/dL) and D-dimer level of 3.3 µg/mL (reference range, 0.0–1.0 µg/mL). Other evaluations (urinalysis, arterial blood gas analysis and chest radiography) showed no significant findings. We found no apparent focus of bacterial infection. We started intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam at 4.5 g four times per day as empirical therapy for febrile neutropaenia.

Outcome and follow-up

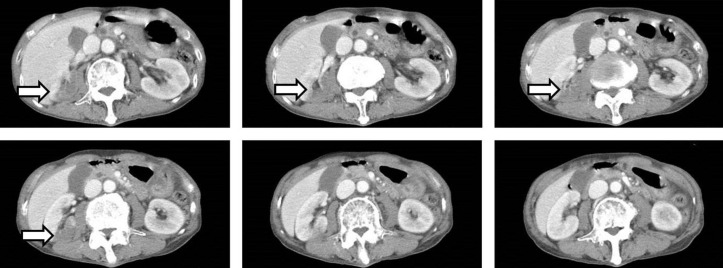

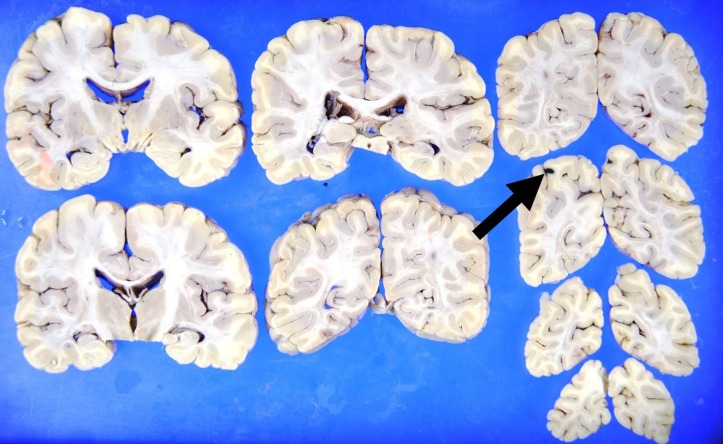

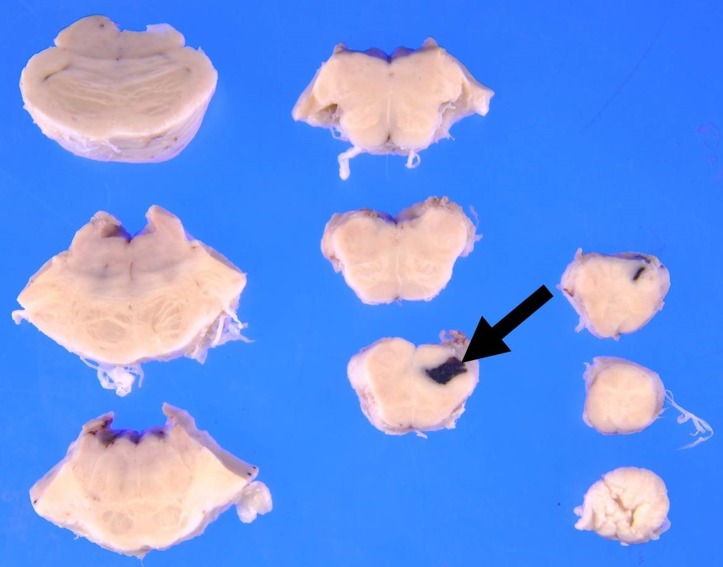

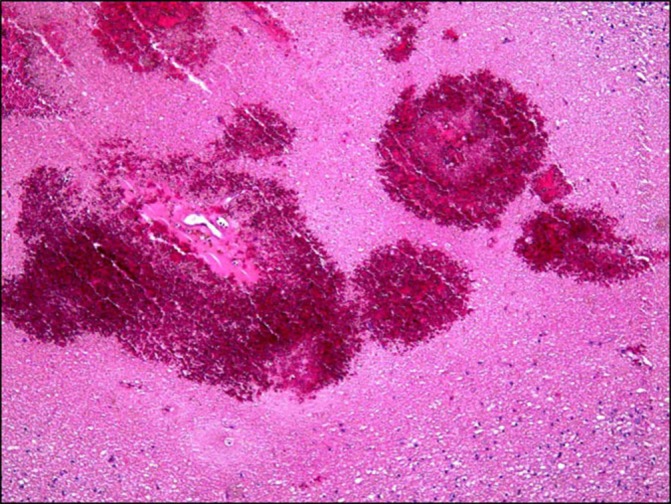

Twelve hours after admission, the patient gradually developed a severe headache. There were no significant changes in the neurological examination (eg, nuchal rigidity). Head CT was performed because of the progressive headache, which was unresponsive to analgaesics; however, the findings were not significant. Two hours later, he complained of nausea with abdominal and lumbar pain, which progressively worsened. An enhanced CT scan showed a focal infarction in the right kidney (figure 1), but there were no critical findings in his chest or abdominal organs. A repeated coagulation profile showed a PT-INR of 1.41, APTT of 37.6 s, fibrinogen level of 356 mg/dL and D-dimer level of 17.1 µg/mL. His blood pressure began to decrease despite a bolus administration of normal saline, and we started empirical therapy with meropenem at 1 g three times per day and vancomycin at 1 g two times per day for suspected septic shock. Despite intravenous norepinephrine, the patient’s blood pressure continued to decrease, and he died 2 hours later. After his death, B. cereus was detected in his blood cultures. An autopsy was performed to determine the cause of death. The autopsy showed multiple areas of intracranial haemorrhage (figures 2–7) and haemorrhagic infarction in the right kidney (figure 8). The chest and abdominal organs were intact, and there were no other significant findings including vasculitis, inflammation or the presence of organisms.

Figure 1.

Enhanced CT shows infarction in the right kidney.

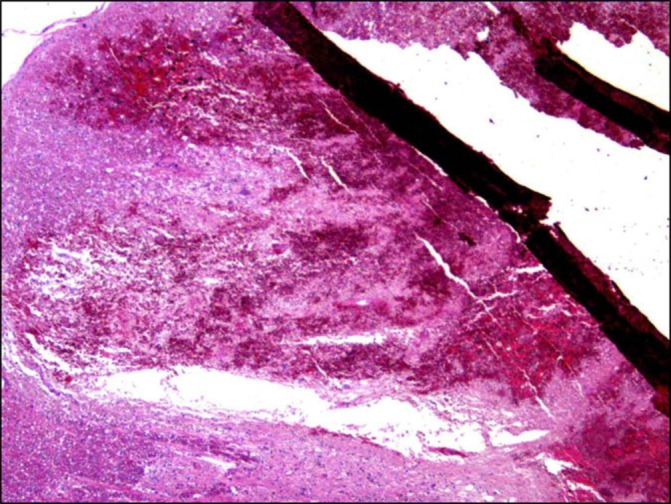

Figure 2.

Gross autopsy findings show haemorrhage in the right occipital lobe.

Figure 3.

Pathological evaluation shows petechial haemorrhage in the right occipital lobe (arrow in figure 2).

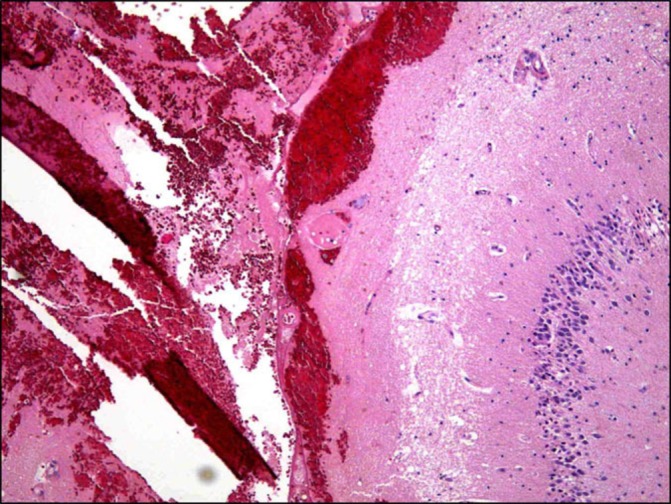

Figure 4.

Gross autopsy findings show haemorrhage in the brainstem.

Figure 5.

Pathological evaluation shows haemorrhage in the medulla (arrow in figure 4).

Figure 6.

Gross autopsy findings show haemorrhage in the left hippocampus.

Figure 7.

Pathological evaluation shows haemorrhage along the surface of the left hippocampus.

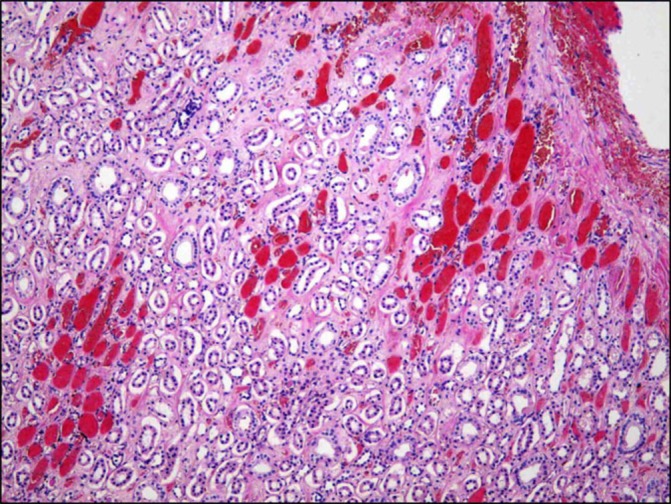

Figure 8.

Pathological evaluation shows intratubular haemorrhage in the right kidney.

Discussion

This patient had an exceedingly acute course that led to his death within 1 day after admission. The patient was apparently well the day before the admission, and this was his first hospital admission after being diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukaemia. In an immunocompromised host, B. cereus septicaemia can sometimes present with an acute course, and it is often accompanied by severe headache and intracranial haemorrhage, as in our case.3–5 B. cereus is known to produce a necrotising exotoxin1 that can result in necrosis and haemorrhage. The clinical course is progressive and may lead to coagulopathy of multiple organs, especially in patients with haematologic malignancies. In a previous report, the frequency of haemorrhagic or ischaemic complications in patients with leukaemia with B. cereus septicaemia was 54%. These complications included subarachnoid haemorrhage, intracranial haemorrhage, haemorrhagic pneumonia and acute tubular necrosis of the kidney.3 In our patient, multiple intracranial haemorrhages and kidney infarctions were noted despite only mild abnormalities in the coagulation profile.

Notably, the patient complained of abdominal pain a few hours after admission. B. cereus is also a causative agent of food poisoning.1 Unfortunately, at the time of presentation, we did not obtain a detailed history about the patient’s diet, such as the consumption of reheated fried rice as a source of infection. It is possible that this patient’s abdominal pain resulted from an intestinal infection with B. cereus.

Akiyama et al3 reviewed cases of B. cereus septicaemia in patients with leukaemia and found that 69% of these patients had acute myelogenous leukaemia. Furthermore, patients with leukaemias other than acute myelogenous leukaemia died 8 to 10 days after presentation, while most patients with acute myelogenous leukaemia died 12 hours to 3 days after presentation (except for two patients who died at 5 and 6 days, respectively).

Inoue et al8 assessed 68 patients with growth of B. cereus in their blood culture during a 7-year period and found that 34% of these patients had haematologic malignancies. Furthermore, they reported a significant association between a poor prognosis and the presence of acute leukaemia, central nervous system symptoms or an extremely low neutrophil count. Indeed, our patient had acute myelogenous leukaemia, intractable headache and neutropaenia and exhibited an extremely poor prognosis.

The present case indicates that when patients with haematologic malignancies (especially acute leukaemia) who are undergoing chemotherapy present with central nervous system symptoms and neutropaenia, we should consider immediately administering empirical therapy with vancomycin to cover B. cereus infection.

Learning points.

Patients with leukaemia are predisposed to ischaemic/haemorrhagic complications of B. cereus septicaemia.

Obtaining a detailed history including diet information, such as the consumption of reheated fried rice, might contribute to the identification of B. cereus infection.

Given the fulminant nature of B. cereus septicaemia and associated high mortality rate, empirical therapy with vancomycin should be promptly instituted for suspected B. cereus septicaemia in patients with haematologic malignancies who are receiving chemotherapy, especially those with acute leukaemia, neurological symptoms and profound neutropaenia.

Footnotes

Contributors: YSH wrote the manuscript. SK, YN and YS critically reviewed it.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Drobniewski FA. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clin Microbiol Rev 1993;6:324–38. 10.1128/CMR.6.4.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginsburg AS, Salazar LG, True LD, et al. Fatal Bacillus cereus sepsis following resolving neutropenic enterocolitis during the treatment of acute leukemia. Am J Hematol 2003;72:204–8. 10.1002/ajh.10272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akiyama N, Mitani K, Tanaka Y, et al. Fulminant septicemic syndrome of Bacillus cereus in a leukemic patient. Intern Med 1997;36:221–6. 10.2169/internalmedicine.36.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marley EF, Saini NK, Venkatraman C, et al. Fatal Bacillus cereus meningoencephalitis in an adult with acute myelogenous leukemia. South Med J 1995;88:969–72. 10.1097/00007611-199509000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motoi N, Ishida T, Nakano I, et al. Necrotizing Bacillus cereus infection of the meninges without inflammatory reaction in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report. Acta Neuropathol 1997;93:301–5. 10.1007/s004010050618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiyomizu K, Yagi T, Yoshida H, et al. Fulminant septicemia of Bacillus cereus resistant to carbapenem in a patient with biphenotypic acute leukemia. J Infect Chemother 2008;14:361–7. 10.1007/s10156-008-0627-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelley JM, Onderdonk AB, Kao G. Bacillus cereus septicemia attributed to a matched unrelated bone marrow transplant. Transfusion 2013;53:394–7. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue D, Nagai Y, Mori M, et al. Fulminant sepsis caused by Bacillus cereus in patients with hematologic malignancies: analysis of its prognosis and risk factors. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51:860–9. 10.3109/10428191003713976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]