Abstract

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for cord compression is a safe and effective procedure with good outcomes. However, worsening of myelopathy is the most feared adverse event of the surgery. We report the case of a 36-year-old male patient who presented with an acute non-traumatic C5–6 cervical disc herniation causing incomplete quadriparesis. He underwent an uncomplicated ACDF at C5–6, and after an initial period of improvement, he developed a delayed onset of an anterior cord syndrome on day 3, without any discerning cause. We have reviewed similar cases reported in the literature and believe that our patient’s postsurgical course is consistent with a delayed ischaemic/reperfusion injury to the cord following surgical decompression and restoration of blood flow through the anterior spinal artery and we make suggestions for management of such clinical events.

Keywords: mechanical ventilation, neuroimaging, neurological injury, spinal cord, neurosurgery

Background

The complications of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) most often reported in the literature include dysphagia, dural tear, hoarseness secondary to superior or recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, esophageal tear, vertebral artery injury and graft relation problems. Worsening of myelopathy or progression of existing neurological deficit is the most feared adverse event of this procedure and that is most often secondary to an epidural haematoma. However, in the setting of surgical relief of an acute compressive myelopathy, the worsening could be due to a vascular insult such as ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Non-traumatic cervical disc herniation is rarely the cause of acute quadriparesis with the earliest case reported in literature as recent as 1973. Since then, a further nine cases have been added in the English literature and two cases have been described in Japanese language.

Case presentation

A 36-year-old otherwise healthy male patient with no known medical comorbids presented through the emergency room (ER) with complaints of neck stiffness and cervicobrachial radiculopathy with radiation of pain along the lower back since the last 2 weeks and motor weakness of the limbs since the last 2–3 hours. He denied any trauma or other inciting event. At the onset of the present illness, he had complained of tightness in the chest and was misdiagnosed as acute coronary syndrome. More recently, he had tried physiotherapy and analgesics with no relief of symptoms. Neck movements were immobilised with a soft collar. He had no alarming family history. Routine blood tests, including serum biochemistry, haematology and coagulation profile was normal. At initial examination, he was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 90/50 mm Hg. He was alert and oriented and his cervical spine range of motion was limited particularly right-sided rotation and extension. Neurological examination revealed normal bulk of all muscle groups, decreased tone and power below C4. On the modified Medical Research Council scale, motor power in the upper limbs was grade 3/5 in the right biceps and was 2/5 in the left biceps. In the lower limbs, power was grade 2/5 due to which gait could not be assessed, with incomplete sensory impairment (ASIA/Frankel C). He had preserved light touch, two point discrimination and vibration sense. Deep tendon reflexes were diminished and the plantar response was equivocal. The sensation of bladder distension was intact and the anal and bulbocavernosus reflexes were present. Anal tone was present. Long tract signs were mute secondary to element of spinal shock. With a clinical diagnosis of acute cervical cord compression, an MRI scan of the cervical spine was obtained.

Investigations

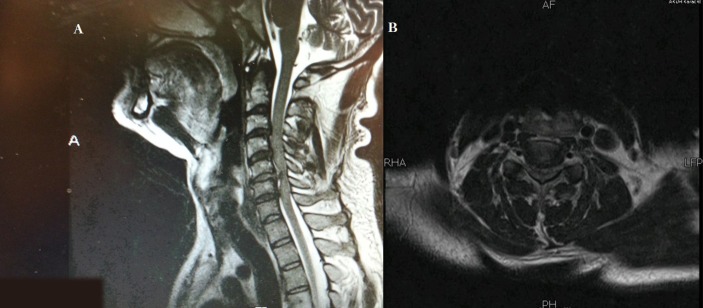

Preoperative MRI scan of the cervical spine (figure 1A,B) showed a diffuse disc bulge at C5–6 with central protrusion causing severe canal stenosis, cord compression and moderate bilateral neural foramina encroachment. There was associated T2 hyperintense signal representing cord oedema just superior to the compression.

Figure 1.

MRI cervical spine preprocedure, in sagittal plane T2 sequence (A) and axial T2 sequence (B), demonstrating annular tear and acute disc prolapse at C5/6 level with subtle hyperintense signal changes in the spinal cord representing oedema and cord compression.

Treatment

Intravenous methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg body weight) bolus was given immediately after the first MRI (within almost 3 hours of the acute cord compression) and was continued at 5.4 mg/kg/hour over the next 24 hours. The hypotension responded to fluid resuscitation. Surgical decompression was offered to the patient and the procedure commenced within 8 hours of onset.

A standard ACDF was performed, using a high-definition intraoperative microscope, via a right-sided approach with plating of a 9 mm iliac crest bone graft. At surgery, it was very clear that the disc had received trauma. It was remarkable by being oedematous and disrupted. A semicircular disc fragment that had herniated into the spinal canal was recovered and adequate decompression was confirmed by exploring the space with a nerve hook in cephalocaudal direction. There was no cerebrospinal fluid leak or bleeding from the disc space during the exploration and no cardiovascular instability during the procedure. From a surgical point of view, the surgery was uncomplicated apart from the observation of non-pulsatile spinal theca after removal of the disc fragment.

Outcome and follow-up

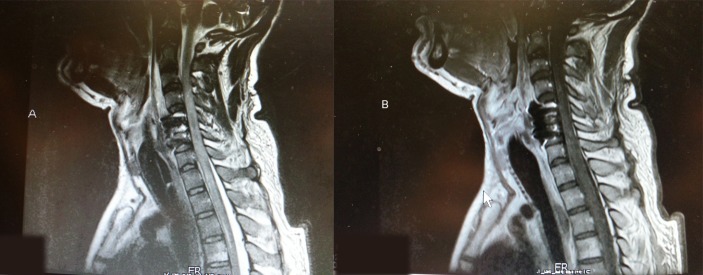

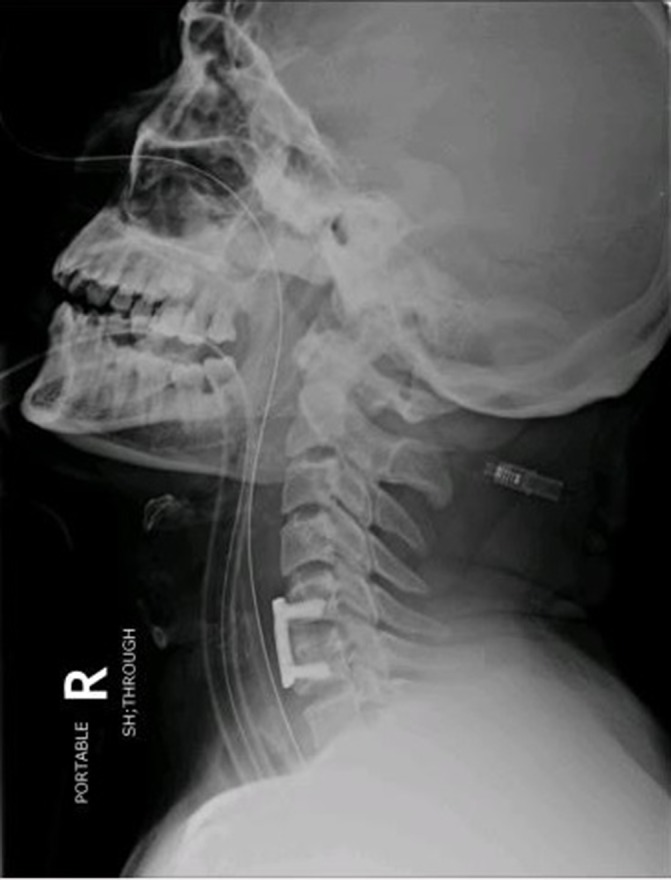

In the immediate postoperative period, neurological assessment showed some improvement in the preoperative quadriparesis. On the modified Medical Research Council scale, motor power improved by one grade to 3/5 in the left biceps and both lower extremities. The rest of the examination remained same. On postoperative day 3, the patient abruptly experienced respiratory distress with oxygen desaturation and this necessitated reintubation and ventilation. The patient was stable from cardiac stand point. Blood pressure was 136/95 mm Hg and pulse was 110 beats per minute. This was also confirmed by the cardiology. Neurological assessment showed the absence of breathing effort and no motor power in the lower limbs. Differential diagnosis with respect to the aetiology included epidural haematoma, graft extrusion or migration or spinal cord injury secondary to ischaemic/reperfusion. A cervical spine radiograph showed the cervical plate and graft in place. An MRI scan of the cervical spine was repeated (figure 2) and this disclosed signal changes in the cord showing hyperintense signals on T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences at C5–6 level suggesting haemorrhage with oedema. Following gadolinium injection of contrast, there was patchy enhancement with luxury perfusion (figure 3A,B). There was no cord compression. The overall appearances in the report were consistent with haemorrhagic infarction of the cord. He had a prolonged intensive care unit stay of 12 days followed by shift-out to special care unit on a portable ventilator, where he had recovered some abdominal-ventilatory effort and grade 2–3/5 power in the upper limbs. He was discharged to rehabilitation with a tracheostomy, gastrostomy and intermittent support by portable ventilator. At last follow-up, 12 months after surgery, he was ventilator independent. He showed improvement in the neurological examination. Bulk was normal and comparable, and tone was mildly increased to grade 2 (Ashworth grading system). On the modified Medical Research Council scale, motor power in all extremities was −4/5. He had intact but decreased sensations till C4 but intact dorsal columns. Deep tendon reflexes were +3 and the plantar response was extensor. The sensation of bladder distension and anal prick was vague but present with improved power in the limbs.

Figure 2.

. X-ray cervical spine lateral view, demonstrating bone graft and plate in place without any migration in the spinal canal.

Figure 3.

MRI cervical spine post procedure; T2 (A) and T1 (B) sequences in sagittal plane, demonstrating hyperintense signal changes in the spinal cord representing haemorrhage. One can appreciate adequate decompression, removal of the disc fragment and surgical implants in place with rest of the postsurgical changes.

Discussion

Non-traumatic cervical disc herniation is rarely the cause of acute quadriparesis with the earliest case reported in literature as recent as 1973.1 Since then, a further nine cases have been added in the English literature and two cases have been described in Japanese language.1–11 Acute paraplegia has also been associated with acute cervical disc and four instances of such a rare occurrence have been reported,12–15 the most recently in 2015 by Bayley et al.12 Of the nine reported cases of acute cervical quadriparesis that we reviewed (table 1), six were males and three were females. The majority of these patients belonged to Asian origin. The ages ranged from 29 to 63 years. The most common level of herniated disc was C4–5 and C6–7, followed by C5–6 as in our case and C3–4. The most common symptoms were of neck pain followed by numbness and the time range from onset of symptoms to surgical intervention ranged from 6 weeks to 7 months. Our case is unique with respect to the time taken from symptoms to intervention, which was 2 weeks.

Table 1.

Summary of previously reported cases with similar clinical presentation

| Authors | Year | Age (years)/sex |

Previous complaint | Spinal canal stenosis | Level (s) |

Other levels affected | Presented with | Neurologic recovery | Operation | Follow-up |

| Lourie et al1 | 1973 | 37/M | Neck pain 2 months | − | C6–7 | − | Quadriparesis | Complete | ACDF | 6 years |

| Joanes2 | 2000 | 63/M | None | − | C4–5 | + | Quadriparesis Sub C-5 |

Incomplete satisfactory | LAMINECTOMY | 12 months |

| Suzuki et al3 | 2003 | 29/M | 5 months numbness all limbs | + | C6–7 | + | Quadriparesis | Incomplete | ACDF +LAMINOPLASTY |

36 months |

| Goh and Li4 | 2004 | 57/M | None | + | C4–5 | + | Quadriparesis | Incomplete | ACDF | 6 months |

| Sanadand et al5 | 2005 | 42/M | None | − | C4–5 | − | Flaccid Quadriplegia |

Incomplete | ACDF | 18 Days |

| Song and Lee6 | 2005 | 44/F | Neck pain 6 weeks | + | C6–7 | + | Myelopathy+ Quadriparesis |

Complete | ACDF | 6 months |

| Tsai et al7 | 2006 | 32/F | 6 months numbness left middle finger | + | C3–4 | + | Progressive Myelopathy+ Quadriparesis |

Complete | ACDF | 18 months |

| Siam et al8 | 2012 | 48/F | Left arm pain+neck pain 2 months | − | C5–6 + C5–7 |

+ | Quadriparesis Sub C-5 | Complete | ACDF | 12 months |

| Chin et al9 | 2012 | 59/M | Bilateral arm+neck pain 7 months | + | C5–6 + C3–6 |

+ | Quadriparesis Sub C-6 | Incomplete satisfactory | ACDF | 16 months |

| This case | 2016 | 36/M | 2 weeks neck pain+arm pain | + | C5–6 | + | Quadriplegia Sub C-6 | Incomplete | ACDF | 12 months |

The onset of symptoms of acute cervical myelopathy can be provoked by trivial activities such as a change of position, to stressful causes such as labour and, notably, during general anaesthesia for another procedure.7 14 16–20 Multilevel degeneration and congenitally narrow canal superimposed on cervical spondylosis are reported risk factors. Kato et al reported a case of acute paraplegia during an MRI examination, in a patient with pre-existing spondylosis.13 Siam et al reported a case in which pre-existing cervical spondylosis together with the rapid and momentary rise of the intradiscal pressure secondary to excessive neck movement on bending forward lead to disk rupture at C5–6 that caused immediate severe compression of the spinal cord.8 This mechanism was observed to be identical to the case reported by Liu et al, although symptoms like weakness were apparent after 2 hours in their case.14 In the current literature, all similar patients were treated surgically. The outcomes varied from complete recovery in four cases to no recovery in three cases. Three cases including our patient had incomplete recovery (table 1).

In our patient, a sizeable herniated disc seemed to have compressed the cord compromising flow in the anterior spinal artery and producing a large area of cord oedema as depicted in figure 1. Surgical decompression of the herniated disc resulted in early improvement of cord function but we postulate that restoration of spinal cord blood flow may have led to disruption in the blood spinal cord barrier and triggered a reperfusion injury resulting in delayed neurological deterioration above and below the surgical level. A similar mechanism was postulated by Chin et al in his report of a 59-year-old male patient who had an incomplete sub-C6 acute quadriparesis secondary to reperfusion injury. Postevent MRI appearance on sagittal T2-weighted sequence and the clinical results of incomplete quadriparesis, without a clear understanding of the pathophysiology, led him to use the term ‘white cord syndrome.’ Our patient exhibited similar features.

Spinal cord ischaemia/reperfusion injury originates from an insufficiency of blood supply to the anterior spinal artery and its branches and appears contingent on factors such as oxygen-derived free radical damage.14 21 22 Mitochondria-dependent apoptosis, TNF-alpha production, specific phospholipid signalling cascades and glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity are factors resulting in neuronal injury in human and animal models.22–25 The experimental literature has shown benefit of various neuroprotective agents particularly potent antioxidants and statins and these may attenuate the neural injury following spinal cord ischaemic/reperfusion injury.22 26–28 Thus, the experimental data suggest that there may be a role for perioperative use of such agents in the context of surgery for acute cord compression.

Learning points.

Urgent assessment and timely relief of ischaemia appears to be the critical factor in preventing reperfusion injury and its consequent irreversible neurological damage.

The role of antioxidants, statins and other neuroprotective agents is supported by the experimental literature and may be considered as prophylaxis against spinal cord ischaemic/reperfusion injury in the perioperative management of acute spinal cord compression.

Acute C5–6 disc herniation may mimic pain presentation similar to acute coronary syndrome.

Footnotes

Contributors: MFK was the primarily assistant in the surgery and was involved in writing the manuscript and literature search. FAH was involved in literature search and helped in writing the discussion. RJ was the primary surgeon and involved in idea, review and correction of the manuscript. MFR was involved in obtaining the radiological pictures and helped in writing the case presentation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lourie H, Shende MC, Stewart DH. The syndrome of central cervical soft disk herniation. JAMA 1973;226:302–5. 10.1001/jama.1973.03230030022005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joanes V. Cervical disc herniation presenting with acute myelopathy. Surg Neurol 2000;54:198 10.1016/S0090-3019(00)00236-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki T, Abe E, Murai H, et al. Nontraumatic acute complete paraplegia resulting from cervical disc herniation: a case report. Spine 2003;28:E125–E128. 10.1097/01.BRS.0000050404.11654.9F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goh HK, Li YH. Non-traumatic acute paraplegia caused by cervical disc herniation in a patient with sleep apnoea. Singapore Med J 2004;45:235–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadanand V, Kelly M, Varughese G, et al. Sudden quadriplegia after acute cervical disc herniation. Can J Neurol Sci 2005;32:356–8. 10.1017/S0317167100004273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song KJ, Lee KB. Non-traumatic acute myelopathy due to cervical disc herniation in contiguous two-level disc spaces: a case report. Eur Spine J 2005;14:694–7. 10.1007/s00586-004-0841-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai H-H, Li T-Y, Chang S-T. Nontraumatic acute myelopathy associated with cervical disc herniation during labor. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2006;19:97–100. 10.3233/BMR-2006-192-309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siam AE, Gouda-Mohamed G-M, Werle S, et al. Acute nontraumatic cervical disk herniation with incomplete tetraplegia. A case report and review of literature. Eur Orthop Traumatol 2013;4:267–72. 10.1007/s12570-013-0182-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin KR, Seale J, Cumming V. "White cord syndrome" of acute tetraplegia after anterior cervical decompression and fusion for chronic spinal cord compression: a case report. Case Rep Orthop 2013;2013:1–5. 10.1155/2013/697918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawaguchi Y, Miyasaka A, Sugaya K. Acute paraplegia due to cervical disk herniation: a case report. Rinsho Seikei Geka 1991;26:1395–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warabi S, Sano S, Torihama Y, et al. Progressive myelopathy caused by multiple cervical disc herniation: a report of two cases. Seikei Geka 1995;46:7414.10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayley E, Boszczyk BM, Chee Cheong RS, et al. Major neurological deficit following anterior cervical decompression and fusion: what is the next step? Eur Spine J 2015;24:162–7. 10.1007/s00586-014-3398-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato Y, Nishida N, Taguchi T. Paraplegia caused by posture during MRI in a patient with cervical disk herniation. Orthopedics 2010;33:448 10.3928/01477447-20100429-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Huang Y, Cai HX, et al. Nontraumatic acute paraplegia associated with cervical disk herniation. J Spinal Cord Med 2010;33:420–4. 10.1080/10790268.2010.11689721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueyama T, Tamaki N, Kondoh T, et al. Non-traumatic acute paraplegia associated with cervical disc herniation: a case report. Surg Neurol 1999;52:204–7. 10.1016/S0090-3019(97)00422-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen SH, Hui YL, Yu CM, et al. Paraplegia by acute cervical disc protrusion after lumbar spine surgery. Chang Gung Med J 2005;28:254–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujioka S. Tetraplegia after coronary artery bypass grafting in a patient with undiagnosed cervical stenosis. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2005;101:1884 10.1097/00000539-200512000-00067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorur A, Aydemir NA, Yurtseven N, et al. Tetraplegia after coronary artery bypass surgery in a patient with cervical herniation. Innovations 2010;5:134–5. 10.1097/IMI.0b013e3181d7553b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewandrowski KU, McLain RF, Lieberman I, et al. Cord and cauda equina injury complicating elective orthopedic surgery. Spine 2006;31:1056–9. 10.1097/01.brs.0000214968.58581.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naja Z, Zeidan A, Maaliki H, et al. Tetraplegia after coronary artery bypass grafting in a patient with undiagnosed cervical stenosis. Anesth Analg 2005;101:1883–4. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180255.62444.7A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan PH. Role of oxidants in ischemic brain damage. Stroke 1996;27:1124–9. 10.1161/01.STR.27.6.1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shan LQ, Ma S, Qiu XC, et al. Hydroxysafflor Yellow A protects spinal cords from ischemia/reperfusion injury in rabbits. BMC Neurosci 2010;11:98 10.1186/1471-2202-11-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okajima K. Prevention of endothelial cell injury by activated protein C: the molecular mechanism(s) and therapeutic implications. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2004;2:125–33. 10.2174/1570161043476429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bazan NG, Marcheselli VL, Cole‐edwards K. Brain response to injury and neurodegeneration. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2005;1053:137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan W, Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Blood-brain barrier permeability to ebiratide and TNF in acute spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 1997;146:367–73. 10.1006/exnr.1997.6533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yavuz C, Demirtas S, Guclu O, et al. Rosuvastatin may have neuroprotective effect on spinal cord ischemia reperfusion injury. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2013;12:1011–6. 10.2174/18715273113129990085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurt G, Gokce EC, Cemil B, et al. Neuroprotective effects of rosuvastatin in spinal cord Ischemia-reperfusion injury in rabbits. Neurosurg Q 2015;25:189–96. 10.1097/WNQ.0000000000000022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu P, Li JX, Fujino M, et al. Development and treatments of inflammatory cells and cytokines in spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mediators Inflamm 2013;2013:1–7. 10.1155/2013/701970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]