Abstract

Prosthetic heart valve thrombosis (PHVT) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with mechanical heart valves. We present a case of recurrent PHVT associated with eosinophilia. A 17-year-old girl underwent aortic and mitral valve replacement for rheumatic heart disease. Over a period of 4 years, she had four episodes of PHVT despite oral anticoagulation with adequate INR. Her investigations revealed eosinophilia which was missed during the previous episodes. No further episodes of PHVT occurred after treatment of eosinophilia with steroids on limited follow-up.

Keywords: valvar diseases

Background

Prosthetic heart valve thrombosis (PHVT) remains a significant clinical problem following mechanical valve replacements.1 2 Even recurrent PHVT may occur infrequently, and is usually attributed to inadequate anticoagulation from a variety of reasons including poor monitoring of anticoagulation therapy, genetic polymorphism and hypercoagulabilty.3 Eosinophilia as a cause of recurrent PHVT, although rarely reported, is not well appreciated. Accordingly, we report a case of recurrent PHVT due to eosinophilia.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old girl underwent double valve replacement with mechanical prosthetic valves (# 27 St Jude mechanical mitral valve and #19 St Jude mechanical aortic valve) for severe rheumatic mitral stenosis, moderate aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation 4 years back. A year later, she presented with worsening dyspnoea, and examination revealed loss of valve click. Evaluation showed restricted motion of mitral valve leaflets on fluoroscopy and transmitral gradient of 10 mm Hg on echocardiography. The INR had been monitored monthly before this episode and it was in therapeutic range in all the visits. She underwent successful thrombolysis with streptokinase 1.5 million units over 1 hour. The residual gradient was 3 mm Hg. Subsequently, she was maintained on warfarin 4 mg per day with a target INR of 3 to 3.5. INR was monitored more closely, which remained in therapeutic range on out patient visits every 15 days. The patient, however, presented with class III symptoms 2 months following the above episode and was found to have stuck mitral (mean diastolic gradient of 23 mm Hg) and aortic valve (peak gradient of 48 mm Hg), for which she underwent mechanical thrombectomy surgically. After surgery, she was maintained on oral anticoagulation with a higher target INR of 3.5 to 4.

A year later, she again presented with worsening dyspnoea and was found to have PHVT of aortic and mitral valves for the third time. She underwent thrombolysis with alteplase 100 mg over 2 hours. Thrombolysis was successful and she was discharged after INR optimisation with oral anticoagulants.

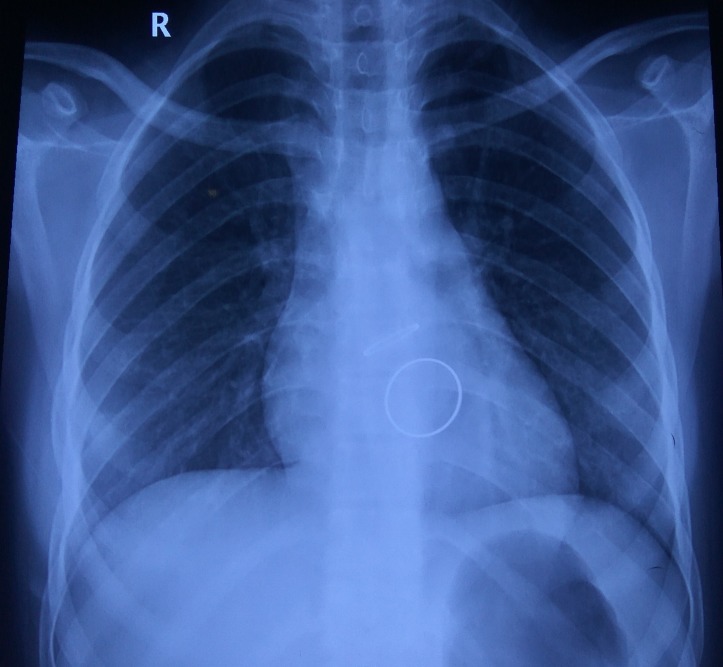

The present admission was the fourth episode of PHVT when she presented with acute-onset exertional dyspnoea and examination revealed loss of mitral valve opening click. Chest X-ray showed evidence of pulmonary venous hypertension (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Xray chest PA during the present admission showing prosthetic mitral valve and pulmonary venous hypertension.

Fluoroscopy showed restricted motion of both mitral valve leaflets with mean diastolic gradient of 18 mm Hg across the mitral valve prosthesis. She was managed with thrombolysis with alteplase 50 mg over 6 hours, after which, the valve successfully opened.

A detailed evaluation was done to determine the cause of recurrent PHVT. Serial blood counts were notable for the presence of eosinophilia with absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of 2500/mm3 (30% eosinophils on differential count). Her previous records were then analysed and showed similar results with AEC of 2500 (18%) in 2014 and 2800 (23%) in 2015, though no detailed evaluation was undertaken in both instances. Admissions in different facilities and lack of appreciation of the role of eosinophilia in causing PHVT led to this error, perhaps. Eosinophilia was suspected as a putative cause for the recurrent episodes of PHVT during this admission. There was no history of atopy or asthma. Peripheral blood smear examination did not show microfilariae. No other possible cause of eosinophilia was identified.

Tropical hypereosinophilia was diagnosed and the patient was accordingly treated with diethylcarbamazine for 21 days and oral steroids 1 mg/kg which were tapered over 6 months. Ten months later, the patient remains clinically stable with AEC of 130/mm3 and normally functioning heart valves.

Discussion

PHVT is the most dreaded complication of mechanical heart valves with an incidence ranging from 0.1% to almost 6% per patient-year of left-sided valves.2 The risk of PHVT depends on the valve type, valve position, status of anticoagulation, the presence of prothrombotic states such as pregnancy, atrial fibrillation.3 The most common cause/risk factor of PHVT is inadequate anticoagulant therapy.1 2

Box. Risk factors for prosthetic heart valve thrombosis.

Inadequate anticoagulation

Prothrombotic states—factor 5 Leiden, Prothrombin gene mutation, Protein C, S deficiency, Eosinophilia

Pregnancy

Site of mechanical valve—tricuspid>mitral>aortic

LV dysfunction

Elevations in the levels of peripheral blood and tissue eosinophils can occur in a wide variety of disease processes that include infectious, allergic, neoplastic, primary haematological disorders and other, often less well-defined (table 1).

Table 1.

Aetiology of eosinophilia

| Primary |

|

| Secondary |

|

| Idiopathic | |

ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; IBD, infallamatory bowel disease; PAN, polyarteritis nodosa; PPI, proton pump inhibitors.

Eosinophilia is a rare and unusual cause of prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. To the best of our knowledge, eosinophilia causing PHVT has been reported only in six instances previously.4–9 The absolute eosinophil count in these cases ranged from 2100 to 6500/mm3. Eosinophilia is common in general population in tropical countries although the exact incidence is unknown. Therefore, eosinophilia may not be thought of as a contributory factor to PHVT, unless one is aware of this possibility. In our case also surprisingly, eosinophilia was not given due importance and was not treated during the previous episodes, leading to recurrent thrombosis despite adequate anticoagulation.

Hypereosinophilia induces cardiovascular damage typically by causing intracardiac thrombosis as in Loefflers endocarditis and endomyocardial fibrosis.10 Prosthetic heart valve thrombosis can be caused by released products from eosinophils which have thrombogenic potential. In particular, the major eosinophil basic protein, released during degranulation of eosinophils, inhibits the capacity of thrombomodulin to activate protein C, and this results in an enhanced activity of the thrombotic cascade.11 Both eosinophil basic protein and eosinophil peroxidase interfere with the anticoagulation cascade.12 Further, eosinophils maintain a high tissue factor expression during maturation, providing a main source of preformed tissue factor in the blood, which might be relevant for the thrombogenesis.13 It is possible that a substantial rise in AEC, as seen in the present patient, can increase thrombogenic activity by these mechanisms and predispose to the development of thrombosis on the implanted prosthetic valve. Thus, we think that eosinophilia in our patient was responsible for recurrent episodes of PHVT. Similar cases might be missed unless the entity is widely recognised.

Learning points.

Recurrent prosthetic heart valve thrombosis (PHVT) despite adequate anticoagulation is rare.

Systemic eosinophilia is a prothrombotic condition.

It is a rare and treatable cause of PHVT.

Increased awareness of possibility of eosinophilia causing PHVT is warranted.

Footnotes

Contributors: NR performed the clinical examination and managed the patient and wrote the paper. SSK managed the patient and revised the manuscript. Both the authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Deviri E, Sareli P, Wisenbaugh T, et al. Obstruction of mechanical heart valve prostheses: clinical aspects and surgical management. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:646–50. 10.1016/S0735-1097(10)80178-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Briët E. Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation 1994;89:635–41. 10.1161/01.CIR.89.2.635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gencbay M, Turan F, Degertekin M, et al. High prevalence of hypercoagulable states in patients with recurrent thrombosis of mechanical heart valves. J Heart Valve Dis 1998;7:601–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awasthy N, Bhat Y, Radhakrishnan S, et al. Recurrent stuck mitral valve: eosinophilia an unusual pathology. Pediatr Cardiol 2015;36:692–3. 10.1007/s00246-015-1102-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zakhama L, Slama I, Boussabah E, et al. Recurrent native and prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Heart Valve Dis 2014;23:168–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jánoskuti L, Förhécz Z, Lengyel M. Unique presentation of hypereosinophilic syndrome: recurrent mitral prosthetic valve thrombosis without endomyocardial disease. J Heart Valve Dis 2006;15:726–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hii MW, Firkin FC, Maclsaac A I, et al. Obstructive prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Heart Valve Dis 2006;15:721–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe K, Tournilhac O, Camilleri LF. Recurrent thrombosis of prosthetic mitral valve in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Heart Valve Dis 2002;11:447–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radford DJ, Garlick RB, Pohlner PG. Multiple valvar replacements for hypereosinophilic syndrome. Cardiol Young 2002;12:67–70. 10.1017/S1047951102000136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinfeldt T, Nienaber CA, Kische S, et al. Cardiac manifestation of the hypereosinophilic syndrome: new insights. Clin Res Cardiol 2010;99:419–27. 10.1007/s00392-010-0144-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukai HY, Ninomiya H, Ohtani K, et al. Major basic protein binding to thrombomodulin potentially contributes to the thrombosis in patients with eosinophilia. Br J Haematol 1995;90:892–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samoszuk M, Corwin M, Hazen SL. Effects of human mast cell tryptase and eosinophil granule proteins on the kinetics of blood clotting. Am J Hematol 2003;73:18–25. 10.1002/ajh.10323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moosbauer C, Morgenstern E, Cuvelier SL, et al. Eosinophils are a major intravascular location for tissue factor storage and exposure. Blood 2007;109:995–1002. 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]