Abstract

Introduction

Identifying stroke as a cause of acute vertigo, dizziness and imbalance in the emergency room is still a clinical challenge. Many patients are admitted to stroke units, but only a minority will have strokes. This imposes a heavy financial burden on the healthcare system. The aim of this study is to develop a diagnostic index test to identify patients with a high risk of having a stroke as the cause of acute vertigo and imbalance.

Methods and analysis

Patients with acute onset of vertigo, dizziness, postural imbalance or double vision within the last 24 hours lasting for at least 10 min are eligible to be included in the study. Patients with clinically proven peripheral or central aetiology will be excluded. In the emergency room, all enrolled patients will undergo standardised neuro-ophthalmological/physiological testing (including video-oculography, mobile posturography, measurement of subjective visual vertical) (EMVERT block 1). Within 10 days, standardised MRI will be performed as a reference test to identify stroke (EMVERT block 2). Data from EMVERT block 2 will be compared with results from block 1 in order to devise a diagnostic index test with a high specificity and sensitivity to predict the risk of stroke in the emergency room.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Munich and will be conducted according to the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, the Federal Data Protecting Act and the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association in its recent version. Study results are expected to be published in international peer-reviewed journals and will be presented at international conferences.

Trial registration number

German Clinical Trial Register: DRKS00008992; Universal trial number: U1111-1172-8719); pre-results.

Keywords: stroke, emergency medicine, vertigo, dizziness, video-oculography, magnetic resonance imaging

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study population includes a broad range of patients presenting with acute vertigo and balance disorders instead of selecting specific subgroups, resembling the daily practice in the emergency room.

Patients will undergo standardised video-oculography measurements during the acute phase of symptoms, as symptoms might be transient or fluctuate in acute vertigo and balance disorders.

The assessment includes measurements of posture, since postural deficits are present in most patients with acute vertigo and balance disorders and isolated postural deficits might be present in posterior circulation strokes.

This study is conducted in only one emergency room of a large university hospital in Germany.

The instrument-based measurements require a mobile device, which has to be made available to the investigator.

Introduction

Acute vertigo, dizziness, balance and gait disorders are among the most frequent symptoms in the emergency department.1 2 In the case of the typical acute vestibular syndrome (AVS), that is, acute vertigo, nausea/vomiting and gait unsteadiness in association with spontaneous nystagmus, clinical differentiation between peripheral vestibulopathy and central brainstem or cerebellar stroke is sufficiently well established.3 4 The origin and diagnostic approaches in AVS have been well studied. Most patients with AVS have peripheral vestibular causes, 25% infratentorial strokes.3 5 Distinguishing both can be challenging, as 50% of patients who had stroke will not have additional focal neurological deficits, and emergency imaging with CT is not sensitive enough (16%).6 Seventeen per cent of patients with ischaemic stroke in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery present with the single symptom of vertigo and dizziness.7 Three bedside vestibular and ocular motor findings can differentiate central from peripheral causes of AVS: the head impulse test, nystagmus and test-of-skew (HINTS).3 4 The horizontal head impulse test (h-HIT) is the single best predictor of stroke in AVS8; a bilaterally normal result in AVS increases the OR of stroke 18-fold. However, the h-HIT is technically demanding to perform and interpretation varies with expertise. Performance of the video-recorded head impulse test (vHIT) considerably helps to distinguish between peripheral and central causes of AVS.9

In clinical practice, most patients in the emergency room do not present with AVS but with symptoms such as isolated vertigo, dizziness and unsteadiness of stance or gait without nystagmus—in the following called acute dysbalance syndrome (ADS). In this case, the clinical diagnosis is more challenging. Differential diagnoses include peripheral vestibular disorders, stroke below the level of the vestibular nuclei, in the cerebellum (hemispheric/vermal), thalamus (thalamic astasia) or hemispheres (pushing behaviour, tilt of subjective postural vertical) as well as intoxications, acute polyneuropathy, peripheral skeletomuscular, cardiovascular (eg, exsiccosis) or psychiatric problems.1 In ADS, HINTS signs are often absent. There have been no systematic studies, which define a common diagnostic approach in ADS.

Therefore, we aim to develop a diagnostic index test to identify stroke in patients presenting with AVS and ADS by use of prospective instrument-based vestibular, ocular motor and balance testing of consecutive patients presenting to the emergency room with acute vertigo/dizziness, double vision, gait instability or falls.

Methods and analysis

Trial flow

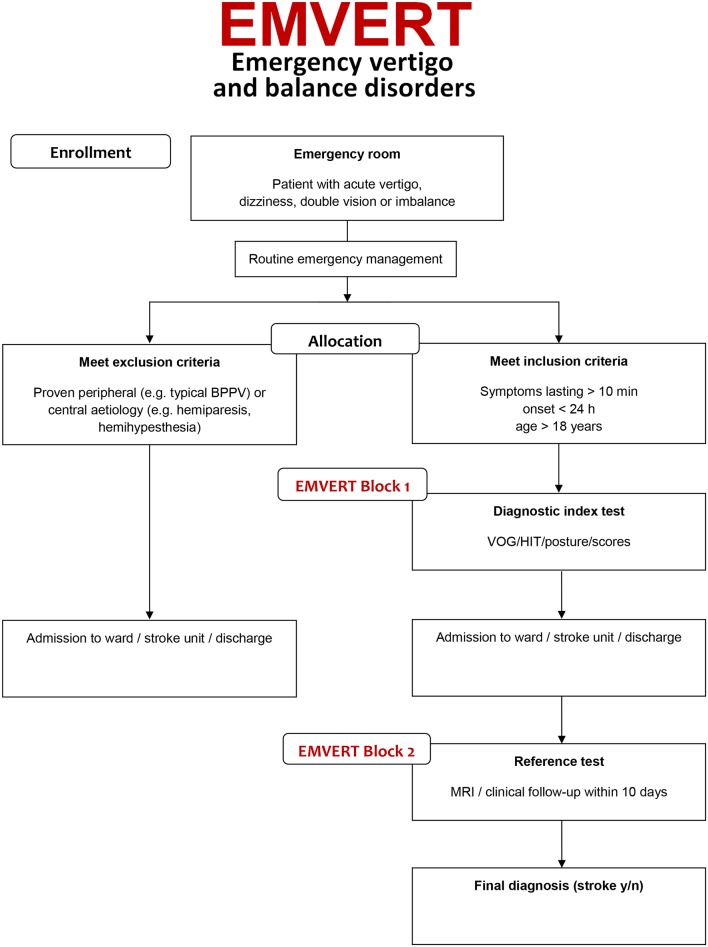

Adult patients with an acute onset of vertigo, dizziness, postural imbalance, gait instability or double vision with symptoms in the last 24 hours and a duration of at least 10 min will be screened prospectively for inclusion in this single-centre trial within business hours. The emergency room physician on duty first sees the patients and carries out routine emergency diagnostic workup and therapy as usual. Then the EMVERT physician is consulted, who performs a structured medical history and standardised clinical examination with an emphasis on ocular motor and vestibular function tests and stance and gait assessment. On the basis of the clinical workup by the EMVERT physician, patients with a clinically proven peripheral or central aetiology will be identified and excluded from the study and further treated in the routine clinical workflow (see figure 1). The following criteria are used to define a syndrome as proven peripheral or central:

Figure 1.

EMVERT trial flow. Study interventions are shown in grey. Proven peripheral or central aetiology (‘no stroke’) includes BPPV with typical findings on diagnostic positioning (nystagmus in the plane of the semicircular canal involved), Menière’s disease with typical recurrent attacks according to Barany Society criteria and other pre-existent disorder with typical presentation in the emergency situation. BPPV, benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo; HIT, head impulse test; VOG, video-oculography.

Proven peripheral aetiology

Typical signs (ie, nystagmus in the plane of the semicircular canal involved on diagnostic positioning manoeuvres) and symptoms of BPPV.

Proven central aetiology

Clinical signs of acute hemiparesis, hemihypesthesia or hemiataxia.

The remaining patients with unclear peripheral or central aetiology of symptoms will be defined as the subpopulation of interest for the EMVERT trial to establish the diagnostic index test (see figure 1). At the start of the trial, the EMVERT physician carries out the workup of EMVERT block 1 (see box 1), which consists of the following parts:

Video-oculography (EyeSeeCam, Fürstenfeldbruck, Germany) recordings of skew deviation, spontaneous nystagmus, gaze holding, smooth pursuit, saccades and vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) suppression. Specification of quantified parameters: degree of skew deviation, nystagmus slow-phase velocity with and without fixation in five different eye positions (including straight ahead) and with provocation, smooth pursuit gain, saccade latency, peak velocity and metric, VOR gain during suppression. Testing will be done with a mobile device located in the emergency department. In order to identify pathological deviations of video-oculography parameters age-matched and gender-matched normal values will be implemented in a cohort of 80 healthy subjects.

Video-oculography and inertial head sensors (EyeSeeCam) to document head impulses. Specification of quantified parameters: vestibulo-ocular reflex gain, compensatory and anticompensatory quick eye movement latency, peak velocity, amplitude. Testing will be done with a mobile device located in the emergency room. Normal values will be derived from testing a matched healthy control group.

Posturography based on accelerometry of postural sway (Wii Balance Board, Nintendo, Kyoto, Japan). Specification of quantified parameters: normalised path length, root mean square and peak-to-peak values during upright bipedal standing with eyes open/closed, upright tandem standing with eyes open/closed and during postural perturbation by pull test in anterior–posterior and mediolateral direction. Testing will be done with a mobile device located in the emergency room. For comparison, healthy controls will be measured with the same setup.

Testing of the subjective visual vertical (SVV) using the bucket test.10 Specification of quantified parameters: mean values of 10 repetitions in a pseudorandomised order will be calculated. Pathological deviations of SVV are considered, if mean values are >2.5 or <−2.5 degrees.

Scores: Dizziness Handicap Inventory, Functional Gait Assessment, Timed Up and Go test, frequency and severity of falls, attacks of vertigo, dizziness, imbalance, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, modified Ranking Scale for patients with stroke, European Quality of Life scale-five dimensions-five levels (EQ-5D-5L), visual analogue scales (VAS), EuroQol-Visual Analogue Scales (EQ-VAS) and ABCD2 score (Age, Blood pressure, Clinical features, Duration, Diabetes).11

Afterwards, the patients in the EMVERT subpopulation will be admitted to the ward or discharged and undergo EMVERT block 2 within 10 days, which is used as the reference test.

Box 1. Summary of neuro-ophthalmological and posturographic measurements as well as scaling and scoring performed at the beginning of the trial in the emergency room (EMVERT block 1). These parameters are the basis for the elaboration of a future diagnostic index test to identify risk of stroke in patients with acute vertigo and balance disorders.

EMVERT block 1

Video-oculography

Saccades

Smooth pursuit

Fixation nystagmus

Spontaneous nystagmus

Vestibulo-ocular reflex suppression

Video head impulse test

Head-shaking nystagmus

Cover test

Measurement of subjective visual vertical—bucket test

Mobile posturography

Eyes open

Eyes closed

Tandem, eyes open

Tandem, eyes closed

Scores and scales

ABCD2 score

Dizziness Handicap Inventory

European Quality of Life scale-five dimensions-five levels, EuroQol-Visual Analogue Scale

Functional Gait Assessment

Modified Rankin Scale

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Timed Up and Go Test

Visual Analogue Scale

EMVERT block 2 will include the following tests (see box 2)

Box 2. MRI protocol and clinical assessment of peripheral or central signs to identify stroke (EMVERT block 2) within 10 days after inclusion (EMVERT block 1).

EMVERT block 2

MRI with 3T scanner

Diffusion-weighted imaging including brainstem fine slicing (3 mm)

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

T1-weighted fast spoiled gradient echo, 1 mm isovoxel

T2-weighted imaging including brainstem fine slicing (3 mm)

T2*-weighted imaging

Time of flight angiography

Clinical assessment of peripheral or central signs

MRI 3T. Specification: the protocol includes diffusion-weighted images including brainstem fine slicing (3 mm), Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery-sequence, T2-weighted images including brainstem fine slicing (3 mm), T2*-weighted images, 3D-T1-weighted sequences (fast spoiled gradient echo 1 mm isovoxel) and time of flight angiography. All images are evaluated by two specialised neuroradiologists for the presence of ischaemic stroke or bleeding.

Clinical observation: Specification: during the observational period of the trial, the dynamics of symptoms will be assessed. If a new symptom occurs which clarifies the aetiology as clinically proven peripheral or central (see above), this observation is included as a definite criterion for or against stroke in the reference test.

Frequency and scope of study visits

Entry (t0; within 24 hours after emergency room consultation): confirming eligibility, obtaining informed consent, structured history taking, standardised neurological workup, scores and scales, video-oculography, video head impulse test, posturography, SVV (see EMVERT block 1).

Study MRI (t1; preferably after day 3 and within 10 days after t0) and clinical assessment of peripheral or central signs (see EMVERT block 2).

Proposed sample size/power calculation

The sample size of 1000 patients to be allocated is planned on the basis of a recruitment period of 2 years. This sample size will allow robust modelling with up to four parameters in a multivariate logistic regression model assuming an a priori stroke probability of 4% in the study population (based on an analysis of patient presentations to the Munich University Hospital Emergency Room from the year 2010). All efforts will be undertaken to avoid dropouts. Of the 1000 patients to be allocated to the trial, a subpopulation of 200 patients (20%) is expected, in which the origin of symptoms can be classified as peripheral or central (stroke) to a high degree of certainty (as compared with an a priori probability of 4% of having stroke) based on the routine clinical testing. For the remaining subpopulation of 800 patients (80%), in which the a priori probability of a stroke is estimated to be 5%, the development and evaluation of a diagnostic index test for stroke is a central aim in order to guide the pragmatic decisions on further imaging and prophylactic therapy. The primary statistical two-sided test for detection of a likelihood ratio of more than 19/4=4.75 in case of a positive index test (LR+) has a power of about 80% to detect an alternative value LR+=247/37=6.6757 in a sample size of 800 patients. Given an a priori probability of pre=5%, the positive predictive value is post+=20% for LR+=4.75, post+=25% for LR+=19/3=6.333 (power 67.2%), post+=26 for LR+=247/37=6.6757 and post+=30% for LR+=57/7=8.1429 (power 98.6%). In a sample of 1072 patients (instead of 800 patients), a power of 80% would be reached for LR+=19/3=6.3333, 382 patients would be sufficient for LR+=57.7=8.1429.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint (stroke or no stroke) will be determined on the basis of the reference test. Clinical and neurophysiological test results from EMVERT block 1 (see above) will be combined to create a diagnostic score for the risk of stroke (predictor). A first outcome measure will be the a priori probability of stroke. The second outcome measure will be sensitivity and specificity, the pair of diagnostic quality of the index test. The index test will be determined based on the receiver operating characteristic curve according to the diagnostic score with specific cut-off values for sensitivity and specificity in order to develop a stroke detection test with high sensitivity and acceptable specificity.

Methods against bias

MRI as part of the reference test will be performed after neurophysiological testing in order to ensure that the reference test is not known at the time of data acquisition for the index test. Data analysis will be done independently of data acquisition with the analyst being unaware of the reference test results. Adherence to standard procedures will be assured by training and supervision of both the emergency physicians and the EMVERT physician. Possible confounders and covariates, namely, gender, age, previous psychotherapy, duration of symptoms and socioeconomic status will be recorded and taken into account in the analysis and in the data interpretation.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Munich on 23 February 2015 (57-15). The trial was prospectively registered in the WHO International Clinical Trial Registry Platform and the German Clinical Trial Registration on 06/08/2015 (main ID: DRKS00008992, Universal trial number U1111-1172-8719) and is currently in the pre-results stage. The diagnostic intervention has a good chance of improving the detection rate of serious causes of the acute symptoms, compared with the usual standard care. Thus, the patient will profit from the additional tests like video-oculography with quantitative head impulse testing. The inconvenience for the patient, in contrast, is minimal. No necessary intervention including medication will be delayed or withheld from patients during the entire study period. The trial will be conducted according to the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), the Federal Data Protecting Act and the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association in its recent version (revision of Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013). The good research practices for cost-effectiveness and the measures used do not involve additional risks (routine techniques). Study results are expected to be published in international peer-reviewed journals and will be presented at international conferences.

Discussion

Although AVS and ADS are very common in the emergency situation, predictive parameters to identify patients who suffer from stroke are sparse, in particular for ADS. Numerous patients are admitted to stroke units, receive extensive diagnostics and long-term treatment without evidence that they will benefit from these procedures.12 There is a need to define objective parameters and supportive instrument-based tests that immediately help to predict whether a patient is suffering from stroke. Thus, the aim of our prospective cohort trial is to identify sets of parameters and tests that can be used in the emergency department to predict the cause and the outcome of acute symptoms. For AVS, we aim to reproduce and validate the HINTS criteria in a large prospective patient cohort and identify possible sensitive additional ocular motor signs. For ADS, a new diagnostic index test for identification of stroke should be established. The innovative aspects of the EMVERT trials are as follows. (1) To enrol a large-scale unselected population of patients with acute vertigo and balance disorders instead of selecting specific subgroups. Thereby, this study better resembles the daily practice in the emergency rooms. (2) To systematically apply video-oculography protocols in the emergency room in the acute phase of symptoms. As pathological ocular motor signs may be transient or fluctuate in acute vertigo and balance disorders early instrument-based documentation is critical to enable a definite diagnosis to be made.13 It is well known that clinical estimation, for example, of the head impulse test may be inaccurate in certain causes, even if performed by a neuro-otological specialist.14 Covert saccades may be overlooked.15 As video-oculography systems become more widely available—at least in larger hospitals—translation of pin-pointed protocols into clinical practice seems possible. (3) To include objective measurements of posture. Postural deficits are present in a majority of patients with acute vertigo and balance disorders. Posterior circulation stroke can manifest with isolated postural deficits.16Standardised assessment of sway and falling tendency have been largely neglected in previous trials on this topic.

Definition of a standardised diagnostic index test for identification of stroke in acute vertigo and balance disorders is an important prerequisite for future multicenter validation. The long-term perspective will improve treatment of affected patients, define treatments tailored to patients’ needs and develop standards of practice including aspects of cost-effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Katie Ogston for copyediting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: KM, KJ and AZ drafted the manuscript. HHM was responsible for the statistical analysis. SB established the methods used in the study. In addition, KM, SB, KJ and AZ planned, coordinated and conducted the study. KJ and AZ are the coordinating principal investigators, KM is the investigator and clinical project manager, SB is responsible for the mobile device used in the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The project is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Health (BMBF) within the context of the foundation of the German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders (DSGZ) (grant number 01 EO 0901).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Munich on 23 February 2015 (ID: 57-15). For inclusion in the study, all patients need to provide written informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Data sharing statement: The EMVERT study is an ongoing prospective trial. Study data will be available through the German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders (DSGZ) after the end of patient recruitment.

References

- 1. Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, et al. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:765–75. 10.4065/83.7.765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, West BT, et al. Dizziness presentations in U.S. emergency departments, 1995-2004. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:744–50. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, et al. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke 2009;40:3504–10. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cnyrim CD, Newman-Toker D, Karch C, et al. Bedside differentiation of vestibular neuritis from central "vestibular pseudoneuritis". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:458–60. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.123596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Norrving B, Magnusson M, Holtås S. Isolated acute vertigo in the elderly; vestibular or vascular disease? Acta Neurol Scand 1995;91:43–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1995.tb05841.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. Lancet 2007;369:293–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60151-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim JS, Lee H. Vertigo due to posterior circulation stroke. Semin Neurol 2013;33:179–84. 10.1055/s-0033-1354600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newman-Toker DE, Kattah JC, Alvernia JE, et al. Normal head impulse test differentiates acute cerebellar strokes from vestibular neuritis. Neurology 2008;70(24 Pt 2):2378–85. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000314685.01433.0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Newman-Toker DE, Saber Tehrani AS, Mantokoudis G, et al. Quantitative video-oculography to help diagnose stroke in acute vertigo and dizziness: toward an ECG for the eyes. Stroke 2013;44:1158–61. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zwergal A, Rettinger N, Frenzel C, et al. A bucket of static vestibular function. Neurology 2009;72:1689–92. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a55ecf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Navi BB, Kamel H, Shah MP, et al. Application of the ABCD2 score to identify cerebrovascular causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Stroke 2012;43:1484–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.646414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim AS, Sidney S, Klingman JG, et al. Practice variation in neuroimaging to evaluate dizziness in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:665–72. 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.02.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blum CA, Kasner SE. Transient ischemic attacks presenting with dizziness or vertigo. Neurol Clin 2015;33:629–42. 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yip CW, Glaser M, Frenzel C, et al. Comparison of the bedside head-impulse test with the video head-impulse test in a clinical practice setting: a prospective study of 500 outpatients. Front Neurol 2016;7:58 10.3389/fneur.2016.00058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weber KP, Aw ST, Todd MJ, et al. Head impulse test in unilateral vestibular loss: vestibulo-ocular reflex and catch-up saccades. Neurology 2008;70:454–63. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000299117.48935.2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee H. Isolated body lateropulsion caused by a lesion of the rostral vermis. J Neurol Sci 2006;249:172–4. 10.1016/j.jns.2006.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.