Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the effect of adding point-of-care (POC) susceptibility testing to POC culture on appropriate use of antibiotics as well as clinical and microbiological cure for patients with suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI) in general practice.

Design

Open, individually randomised controlled trial.

Setting

General practice.

Participants

Women with suspected uncomplicated UTI, including elderly patients above 65, patients with recurrent UTI and patients with diabetes. The sample size calculation predicted 600 patients were needed.

Interventions

Flexicult SSI-Urinary Kit was used for POC culture and susceptibility testing and ID Flexicult was used for POC culture only.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcome: appropriate antibiotic prescribing on the day after consultation defined as either (1) patient with UTI: to prescribe a first-line antibiotic to which the infecting pathogen was susceptible or a second line if a first line could not be used or (2) patient without UTI: not to prescribe an antibiotic. UTI was defined by typical symptoms and significant growth in a reference urine culture performed at one of two external laboratories.

Secondary outcomes: clinical cure on day five according to a 7-day symptom diary and microbiological cure on day 14. Logistic regression models taking into account clustering within practices were used for analysis.

Results

20 general practices recruited 191 patients for culture and susceptibility testing and 172 for culture only. 63% of the patients had UTI and 12% of these were resistant to the most commonly used antibiotic, pivmecillinam. Patients randomised to culture only received significantly more appropriate treatment (OR: 1.44 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.99), p=0.03). There was no significant difference in clinical or microbiological cure.

Conclusions

Adding POC susceptibility testing to POC culture did not improve antibiotic prescribing for patients with suspected uncomplicated UTI in general practice. Susceptibility testing should be reserved for patients at high risk of resistance and complications.

Trial registration number

NCT02323087; Results.

Keywords: urinary tract infections, microbiological diagnosis, culture media, point-of-care testing, antibiotics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was a diagnostic randomised controlled trial allowing for evaluation of patient-relevant outcomes.

Bias in the interpretation process was low and allocation concealment was sufficient

The study took place in general practice, which enhances applicability of our findings to other primary care settings.

Inclusion criteria were quite broad and our findings may be applied to the majority of patients in general practice with suspected urinary tract infection.

We did not succeed to recruit our initially planned sample of patients, but enough patients were recruited to detect a significant difference between the groups.

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common condition in general practice and the second leading cause for the prescribing of antibiotics.1 Resistance rates for the most common uropathogen, Escherichia coli, are rising, and the inappropriate prescription of antibiotics in primary care is known to lead to antibiotic resistance.2–4 Resistant strains of bacteria can cause treatment failure and prolonged symptoms.5–7 Many countries recommend diagnosing UTI based on symptoms and urine dipstick, but combinations of symptoms and dipstick have proven inaccurate in ruling UTI in or out.8 9 In Denmark, there is no national guideline for diagnosing UTI and doctors have varying strategies based on urine dipstick, microscopy, point-of-care (POC) culture and POC culture and susceptibility testing.10 11 Urine culture gives a definite answer for UTI in the symptomatic patient.12 However, sending urine to the microbiological laboratory for culture and susceptibility testing can delay treatment for several days. POC tests for urine culture, and urine culture susceptibility testing are commercially available. They can provide a result within 24 hours, a delay to treatment which the majority of patients would accept.13 The Flexicult SSI-Urinary Kit is commonly used in general practice due to its ease of use and the fact that both culture and susceptibility testing can be performed on the same plate.14 Similar chromogenic agars for culture-only exist, but are less commonly used and have not been validated in general practice. The most commonly used antibiotics in Denmark for treatment of acute UTI are pivmecillinam and sulfamethizole. Resistance rates in E. coli isolates in urine from primary care in Denmark are approximately 30% for sulfamethizole and 5%–10% for pivmecillinam.15 Since other uropathogens can be inherently resistant to pivmecillinam, overall resistance would be expected to be 15%–20% for this drug. We hypothesised that performing a susceptibility test prior to initiation of treatment could target treatment to the individual patient, potentially reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and leading to faster clinical recovery. This study aimed to investigate the effect of POC culture and susceptibility testing against POC culture only on the appropriate use of antibiotics and clinical and microbiological cure for patients with suspected uncomplicated UTI in general practice.

Material and methods

Design

This study was an open, randomised controlled trial (RCT). Patients were individually randomised to having either POC culture and susceptibility testing or POC culture only performed. The design is described in detail in the published protocol.16

Recruitment of practices

An invitation letter was mailed to 200 randomly selected general practices in the Copenhagen area with the aim of recruiting 50 general practitioners (GPs) with experience in using POC culture. The recruited GPs participated in a prestudy instruction course on handling and reading both POC tests and had to pass an online test measuring ability to diagnose UTI based on photographs of urine cultures prior to the inclusion of patients.

Recruitment of patients

The inclusion criteria were: women, 18 years or older, presenting to their GP with dysuria, frequency or urgency, for 7 days or less and for which the GP suspected uncomplicated UTI, including elderly patients above 65, patients with recurrent UTI and patients with orally treated diabetes without complications. The broader definition of uncomplicated UTI was chosen to ensure applicability to a larger group of patients in general practice. The exclusion criteria were: negative dipstick analysis on both leucocytes and nitrites, serious comorbidities, former participation in the study and patients presenting on a Friday (since POC culture is read the following day). All patients had to consent to wait until the next day to receive the result of the POC test before commencing possible treatment. After informed consent, patients were randomised to either POC culture, or POC culture and susceptibility testing. A urine sample from the same portion of urine was sent to the local microbiological laboratory for culture and susceptibility testing. The GP filled out a case report form and the patient was asked to fill out a 7-day symptom diary and return to the GP after 14 days for a control urine sample. Validation of the symptom diary has previously been published.17 Patients were reminded by text messages and telephone calls to return the diary and bring the control urine sample. Each practice kept an anonymous screening log of patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria but who were not included in the study. GPs received no treatment protocol concerning choice of antibiotics but could decide freely on treatment.

Patient involvement

One of the secondary outcome measures was clinical cure. This was measured using a content validated symptom diary, where items were generated through cognitive interviews with patients.17 Patients could state on their consent form whether they wished to be informed about the results of the study. This will be done using a text message with a short summary and a link after publication. Patients were not involved in the design of the study. All recruiting practices received a poster displaying information about the trial to hang in the waiting room, so patients could enquire about participation in case they were not approached regarding this.

Point-of-care tests

Culture-only group: The ID Flexicult (SSI DIagnostica, Denmark) is a chromogenic agar allowing identification and quantification of (1) E. coli, (2) other Enterobacteriaceae (Gram-negative rods), (3) enterococci, (4) Proteus spp, (5) Staphylococcus saprophyticus and (6) Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The plate is inoculated with freshly voided urine using a 10 µL loop needle and incubated at 35°C overnight. It is read the following day, but negative culture can only be determined after 24 hours. Significant growth was prespecified as ≥103 colony-forming units per millilitre (cfu/mL) for E. coli and S. saprophyticus and ≥104 cfu/mL for other typical uropathogens in accordance with European guidelines.12

Culture and susceptibility testing group: The Flexicult SSI-Urinary Kit (SSI Diagnostica, Denmark) is an agar dish consisting of a large compartment containing the same agar material as in the ID Flexicult and five small compartments, each containing agar with a specific antibiotic: (1) trimethoprim, (2) sulfamethizole, (3) ampicillin, (4) nitrofurantoin and (5) mecillinam. The agar plate is flooded with freshly voided urine for 3–5 s. Any excess urine is discarded. The plate is incubated and handled in the same way as the ID Flexicult. Significant growth was prespecified (advised by manufacturer) to ≥103 cfu/mL for any uropathogen.

Reference culture in the microbiological laboratory

Urine samples were sent by special delivery service to the reference microbiological laboratories at the Department of Clinical Microbiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Herlev, Denmark or the Department of Clinical Microbiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre, Denmark. Urine samples were analysed on Inoqul A Bi-plate (CHROMagar and blood agar) with 10 µL on each half of the agar. The susceptibility pattern was determined on Mueller Hinton agars with disks containing antibiotics, including mecillinam, trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, sulfamethizole, ampicillin and ciprofloxacin. All samples were quantified. Significant growth was defined as growth of ≥103 cfu/mL for E. coli and S. saprophyticus, ≥104 cfu/mL for other typical uropathogens and ≥105 cfu/mL for possible uropathogens. Plates with growth of more than two uropathogens were labelled as mixed cultures and classified in the analysis as negatives.

Randomisation and concealment of allocation

The randomisation code was produced by an online random number generator as permuted block randomisation in blocks of 10 by the investigators. The allocation of each included patient was placed in an opaque, sequentially numbered, sealed envelope, which was opened in general practice after inclusion of the patient.

Outcomes

Primary outcome: Appropriate treatment was defined as either (1) if the patient had UTI in the reference: to prescribe a first-line antibiotic to which the infecting pathogen was susceptible; (2) if the patient had UTI but was allergic to the antibiotic or the pathogen was resistant to all first-line antibiotics: to prescribe a second-line antibiotic or (3) if the patient did not have UTI in the reference: not to prescribe an antibiotic. Secondary outcomes: Clinical cure was defined as the patient reporting herself as symptom free in the symptom diary on day 5 (4 days after initiation of treatment). Microbiological cure was defined as no significant growth in the control urine sample after 14 days.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation was performed assuming the proportion of appropriately treated patients in the control group would be 70%–80%, since POC culture had proven quite accurate and local resistance rated to pivmecillinam and sulfamethizole was 6%–10% and 30%–40%, respectively.14 18 To detect a statistically significant (α=0.05) 10 percentage point difference between the two groups with 80% probability, assuming an intraclass correlation of 0.2 between patients in the same practice, a sample of 600 patients was needed. To take possible dropouts and subanalyses into account, the study originally aimed at enrolling 750 patients.

The distributions of baseline presentation characteristics were compared between the randomisation groups using χ2 tests. Investigated variables were: age, number of days with symptoms, key symptoms (dysuria, frequency and urge), complicating factors and reference culture and susceptibility test. Primary and secondary outcomes were analysed in logistic regression models; clustering within practices was adjusted for by generalised estimating equations. Patient factors (age, number of days with symptoms, key symptoms, and complicating factors) and practice factors (number of GPs and organisation of practice) were investigated for effect modification on the primary outcome. All analyses were performed as intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses. The significance level was 5%. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS V.9.4 for Windows V.7, SAS Institute.

Results

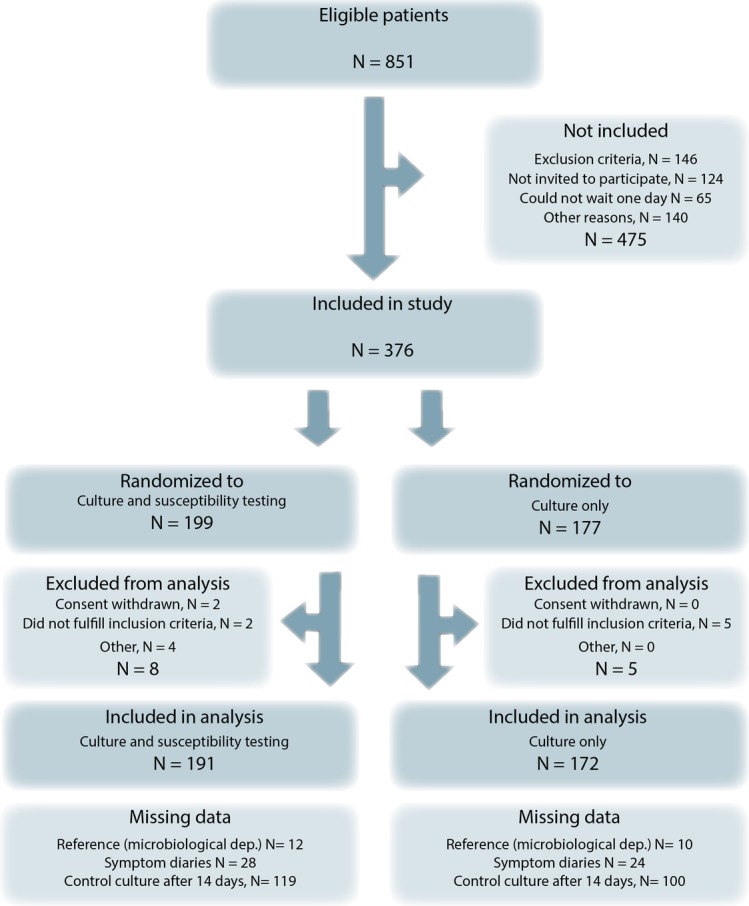

Twenty general practices with a total of 45 GPs were recruited from the Copenhagen area and they screened 851 patients for eligibility between 1 March 2015 and 1 May 2016. Of these, 376 patients agreed to participate: 199 were randomised to culture and susceptibility testing, and 177 were randomised to culture only. Thirteen patients were excluded from the analysis, leaving a total of 363 patients with data on at least one of the outcomes to be included in the analysis. An overview of the inclusion and exclusion of patients can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Inclusion flow chart.

Patient characteristics and distribution between groups can be seen in table 1. Most of the baseline variables did not differ significantly between groups, but the proportion of patients who were over 65 years or who had recurrent UTI or diabetes (complicated cases of uncomplicated UTI) differed significantly. The prevalence of confirmed UTI (significant growth of uropathogens in the reference standard) and susceptibility pattern in the reference standard did not differ between groups.

Table 1.

Distribution of baseline data between the randomisation groups

| Culture and susceptibility, n (%) | Culture only, n (%) | p | |

| Age groups | |||

| Age below 50 years | 105 (55) | 83 (48) | NS |

| Age 50 years or above | 86 (45) | 89 (52) | NS |

| Number of days with symptoms | |||

| Symptoms for less than 3 days | 77 (41) | 67 (40) | NS |

| Symptoms 3 days or more | 109 (59) | 101 (60) | NS |

| Key symptoms (dysuria, frequency, urge) | |||

| One or two key symptoms | 75 (40) | 67 (40) | NS |

| Three key symptoms | 111 (60) | 100 (60) | NS |

| Complicating factors | |||

| Any complicating factor | 43 (26) | 62 (38) | 0.0209 |

| Elderly above 65 years | 34 (20) | 50 (29) | 0.0496 |

| Recurrent UTI (>3 past year) | 11 (6) | 6 (4) | NS |

| Uncomplicated diabetes | 11 (6) | 17 (10) | NS |

| Reference culture and susceptibility test | |||

| Significant growth of uropathogens (UTI) | 100 (62) | 104 (64) | NS |

| Trimethroprim resistance | 27 (26) | 21 (20) | NS |

| Sulfamethizole resistance | 29 (29) | 24 (24) | NS |

| Nitrofurantoine resistance | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | NS |

| Mecillinam resistance (pivmecillinam) | 15 (14) | 9 (9) | NS |

Numbers are total numbers with percentages in brackets.

NS, non-significant; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Three quarters (75%) of the patients were appropriately treated in the culture-only group and two-thirds (67%) were appropriately treated in the culture and susceptibility testing group. This difference was significant both in the unadjusted analysis and when controlled for baseline characteristics. Subgroup analyses on young patients without comorbidity and patients who were elderly or who had diabetes or recurrent UTI showed that young patients with no comorbidities were significantly more appropriately treated in the culture-only group compared with the culture and susceptibility group. The difference was not significant for patients who were elderly or who had diabetes or recurrent UTI, although culture-only group was still superior to culture and susceptibility testing (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of primary and secondary outcomes between the randomisation groups

| n | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Unadjusted analysis | |||

| Odds for appropriate prescribing if culture only | 341 | 1.44 (1.03 to 1.99) | 0.0311 |

| Odds for being symptom free on day 5 if culture-only | 308 | 0.91 (0.56 to 1.49) | NS |

| Odds for no significant bacteriuria on day 14 if culture only | 144 | 1.15 (0.62 to 2.13) | NS |

| Adjusted for complicating factors | |||

| Odds for appropriate prescribing if culture only | 324 | 1.65 (1.12 to 2.42) | 0.0112 |

| Odds for being symptom-free on day five if culture only | 293 | 0.89 (0.55 to 1.44) | NS |

| Odds for no significant bacteriuria on day 14 if culture only | 140 | 1.23 (0.64 to 2.38) | NS |

| Subgroup analysis (unadjusted) | |||

| Odds for appropriate prescribing for young patients without comorbidities if culture only | 222 | 1.79 (1.06 to 3.02) | 0.0300 |

| Odds for appropriate prescribing for patients that were elderly, had diabetes or had recurrent UTI if culture only | 102 | 1.37 (0.78 to 2.41) | NS |

OR, Odds for having a positive outcome if randomised to culture-only (ID Flexicult) compared with culture and susceptibility testing (Flexicult SSI-Urinary Kit).

NS, non-significant; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Table 3 shows the distribution of patients and the reasons why they were labelled as appropriately or inappropriately treated. Overtreatment of patients without UTI was the major reason for inappropriate treatment and was almost equally distributed between groups. Undertreatment was slightly higher in the culture and susceptibility group. Surprisingly, treatment with an antibiotic to which the infecting pathogen was resistant was higher in the culture and susceptibility group. None of the individual differences was significant.

Table 3.

Reasons for appropriate and inappropriate choice of treatment and distribution of patients between groups

| Culture and susceptibility, n (%) | Culture only, n (%) | |

| Appropriate choice of treatment | 120 (67) | 121 (75) |

| UTI and first-line antibiotic and pathogen susceptible | 85 (47) | 90 (56) |

| UTI, second-line antibiotic and pathogen susceptible and first-line antibiotic impossible due to allergies or resistance | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No UTI and no antibiotic | 35 (20) | 31 (19) |

| Inappropriate choice of treatment | 59 (33) | 41 (25) |

| UTI and no antibiotic | 13 (7) | 7 (4) |

| UTI and antibiotic but uropathogen not susceptible to antibiotic | 10 (6) | 7 (4) |

| UTI and inappropriate second-line antibiotic | 3 (2) | 0 (0) |

| No UTI and antibiotic | 33 (18) | 27 (17) |

The overall difference was significant as shown in table 2, but none of the individual differences was significant.

NS, non-significant; UTI, urinary tract infection.

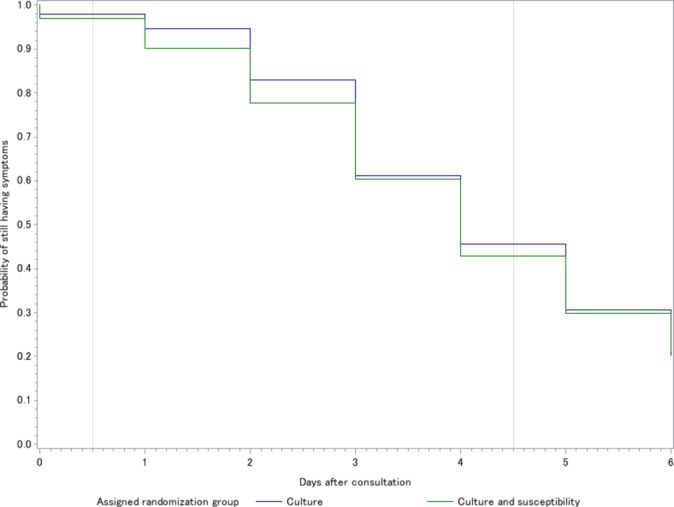

Three hundred and eight patients (85%) had data for the secondary outcome, clinical cure on day 5. Cure rates were equal between groups, and there was no significant difference between the proportions of patients cured on day 5 (see table 2 and figure 2). One hundred and forty-four patients (40%) delivered a control urine sample after 14 days. There was no significant difference in microbiological cure rate between groups.

Figure 2.

Cure rates for the two groups. The level of the coloured lines indicates the proportion of patients still having symptoms. Day 0 is the evening of the day of the consultation. The first vertical grey line indicates initiation of treatment (the morning after the consultation); the second vertical grey line indicates the data used for calculation of the secondary outcome: clinical cure on day 5 (4 days after consultation).

In accordance with the protocol, we investigated whether practice or patient factors could modify the primary outcome (effect modification). Neither practice factors (size and organisation of participating practices) nor patient factors (any complicating factor, age, diabetes, number of UTIs and number of key symptoms at inclusion) modified the effect of the intervention significantly.

Six patients in the culture-only group had the wrong test performed (culture and susceptibility testing). Per protocol analysis essentially reproduced our findings with culture-only still leading to 75% appropriate treatment and culture and susceptibility testing to 67% appropriate treatment (p=0.05 unadjusted and 0.02 adjusted).

Discussion

Patients in the POC culture group received significantly more appropriate prescribing than patients in the POC culture and susceptibility group. There was no difference in clinical recovery, despite the difference in appropriate prescribing. This may be partly due to the fact that pivmecillinam has been shown to have a clinical and microbiological effect despite the infecting pathogen being resistant in vitro.5

We aimed at investigating the effect of adding susceptibility testing to POC culture on the appropriate use of antibiotics so the RCT was the most appropriate design.19–21 We succeeded in enrolling a sample of GPs with experience in POC culture. These GPs recruited a sample of patients with symptoms of uncomplicated UTI, which was sufficient to detect a small but significant difference between appropriate prescribing based on two different POC culture tests. The inclusion criteria broadened the usual strict definition of uncomplicated UTI, which ensures applicability of our findings to a much broader group of patients in general practice. It may be controversial to include patients with diabetes and recurrent UTI in a sample of patients with uncomplicated UTI, but since these conditions are very common among patients with suspected UTI in general practice and they could be safely included, we decided to include these conditions and investigate whether they modified the effect of the intervention on the outcome. Both the subgroup analysis and the investigation of effect modification indicated that these patients’ disease was not more complicated than that of young women with no comorbidity. We did not recruit our initially planned sample, but the difference between groups turned out to be larger than originally expected when sample size was calculated. A type I error in determining the superiority of the ID Flexicult is possible since the significance level was not overwhelming, but a type II error in failing to detect the expected superiority of the Flexicult SSI-Urinary Kit is unlikely. Subgroup analysis could easily be subjected to both type I and type II errors and should be interpreted with caution.

Bias in the interpretation of the test was low as described previously.22 GPs were blinded to the result of the reference at the time of deciding on treatment; POC test and reference were performed on the same portion of urine; the reference was adequate for ruling disease in or out and all data were included in the analysis. Allocation was concealed using sealed envelopes. It is very unlikely that GPs introduced any selection bias due to strong beliefs of the effect of one of the tests. Applicability of the results was also high, since patients, GPs and tests were very similar to those which would be relevant in daily practice. Patients with negative dipstick results were excluded. Spectrum bias should therefore be considered if the tests are applied to all patients regardless of their dipstick result.

The study was subjected to clinical review bias in the interpretation process, since the interpreter of the POC tests was not blinded to clinical history. The two groups did not differ in terms of number of symptoms or number of days with symptoms, and patient factors did not seem to have different effects on the two groups, so the difference in this bias between groups was probably minimal. Confirmation bias in the interpretation process could also be present, since treatment had to be initiated based on the result of the test and only patients with suspected UTI were included. GPs were slightly more compliant with regard to the familiar test (culture and susceptibility testing) than with the new test. However, since overtreatment was similar in the two groups, it does not seem to have had a major effect (see online supplementary appendix 1). The number of patients recruited in the two groups was not the same, but if allocation concealment was insufficient leading GPs to avoid recruiting patients when the patient was intended to receive culture without susceptibility testing, we would have expected more patients with any complicating factor in the culture and susceptibility groups, but the opposite was the case. The unequal distribution of patients between the groups was more likely random due to the GPs not recruiting to number. Our trial was open label and it is possible that ascertainment bias was present if GPs had a stronger belief in one of the tests. Six patients had the wrong test performed, but per-protocol analysis reproduced the ITT findings, suggesting that this was unintentional. The reference, sending urine in boric acid for culture at the microbiological laboratory, has its flaws as previously described.22 However, these flaws should have a similar effect on the two groups, since the distribution of growth and the resistance pattern did not differ significantly between groups.

bmjopen-2017-018028supp001.pdf (147.5KB, pdf)

There are no previous diagnostic RCTs comparing the use of POC culture versus POC culture and susceptibility testing in general practice. A study from 2010 investigated five different management strategies and found differences in antibiotic use (more antibiotics were used when treatment was based only on symptoms) but no difference in patient recovery.23 They found the lowest antibiotic use in the group in which antibiotics were delayed (77%). In comparison, total antibiotic use was 76% for culture only and 73% for culture and susceptibility testing in this study.

The significant overall difference in appropriate prescribing between the groups was driven by three factors (none of them individually significant): first, undertreatment; second, treatment with an antibiotic to which the infecting pathogen was resistant and third, inappropriate choice of a second-line antibiotic. The first factor, undertreatment, could be partly due to a slightly lower sensitivity of the Flexicult SSI-Urinary Kit22 and partly to GPs being generally more compliant with a negative result in this group (see online supplementary appendix 1). The second factor, treatment with an antibiotic to which the infecting pathogen was resistant, was surprising and could be partly due to the fact that susceptibility testing in general practice is not always accurate11 and partly due to ID Flexicult possibly being a better test to identify pathogens, thereby identifying the inherent susceptibility pattern. Correct identification of pathogens is essential for determining the inherent susceptibility pattern, since the inherent susceptibility pattern does not necessarily show on the culture plate.24 The GPs in our study may have relied too much on their susceptibility test and only looked up the inherent susceptibility when they were forced to do so. The study on the accuracy of the two tests investigated in this study showed that the GPs identified pathogens correctly in about 60% of the positive cultures.22 A post hoc analysis showed that the ID Flexicult was actually significantly better at identifying uropathogens than the Flexicult SSI Urinary kit. However, the most common uropathogen, E. coli, does not have inherent resistance to first-line antibiotics, so this second factor may just be a random finding. The third factor, inappropriate choice of a second-line antibiotic, happened in a few cases and none of them had an obvious reason, such as identification of resistance on the practice susceptibility test or patient allergies. The factor expected to drive the difference between the groups: choice of an antibiotic to which the infecting pathogen was resistant, happened in few cases with no difference between the groups. Resistance levels in Denmark are low, and in countries with high resistance rates, the results would probably be different. It remains to be investigated if adding POC susceptibility testing in a high-resistance setting improves prescribing.

The findings of this study support current recommendations that uncomplicated UTI should not have susceptibility testing performed prior to initiation of treatment. Women generally accepted delaying treatment for 1 day to await the POC culture result and inappropriate treatment was low in both groups. If all patients had been treated with first-line antibiotics based on clinical history and positive dipstick finding, then about 45% of patients would have been inappropriately treated compared with 29% in this study (data not shown). Also, total antibiotic use was lower than previously described in a similar setting.23 Based on these results, performing POC culture prior to treatment for patients with uncomplicated UTI seems rational, but adding POC susceptibility testing should be reserved for those patients at high risk of a resistant infection or complications or for geographical areas with high levels of resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the GPs and patients who took part in this study, as well as the UC-Care Research Centre at the University of Copenhagen. We would also like to thank Paul Glasziou and his colleagues at Bond University for their kind support and feedback.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. The corresponding author drafted the manuscript and all other authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. AH conducted the study supported by all other authors. She drafted the first manuscript and all other authors revised the entire manuscript critically and approved the final version for publication. She also serves as the guarantor for the study. VS has mainly supervised statistics and NFM has mainly supervised technical issues regarding the POC tests and microbiological culture. All authors have approved the final version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This study was funded by: (a) 2016, the University of Copenhagen (b) Læge Sofus Carl Emil Friis og Hustru Olga Doris Friis’ legat, (c) SSI Diagnostika (materials). None of the funders had any influence on study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or writing of the article or the decision to submit it for publication. None of the authors is financially influenced by any of the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: All procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for the Capital Region of Denmark (ref. no: H-3-2014-107). All patients gave written informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All authors had access to and can take responsibility for data and analysis. The authors commit to making the relevant anonymised patient level data available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Petersen I, Hayward AC. Antibacterial prescribing in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60(Suppl. 1):i43–i47. 10.1093/jac/dkm156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:c2096 10.1136/bmj.c2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, et al. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 2005;365:579–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70799-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta K, Scholes D, Stamm WE. Increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens causing acute uncomplicated cystitis in women. JAMA 1999;281:736–8. 10.1001/jama.281.8.736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monsen TJ, Holm SE, Ferry BM, et al. Mecillinam resistance and outcome of pivmecillinam treatment in uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in women. APMIS 2014;122:317–23. 10.1111/apm.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler C, Hillier S, Roberts Z. Antibiotic-resistant infections in primary care are symptomatic for longer and increase workload: outcomes for patients with E. coli UTIs. Br J Gen Pract 2006686–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNulty CA, Richards J, Livermore DM, et al. Clinical relevance of laboratory-reported antibiotic resistance in acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006;58:1000–8. 10.1093/jac/dkl368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K, et al. Developing clinical rules to predict urinary tract infection in primary care settings: sensitivity and specificity of near patient tests (dipsticks) and clinical scores. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:606–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knottnerus BJ, Bindels PJ, Geerlings SE, et al. Optimizing the diagnostic work-up of acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections. BMC Fam Pract 2008;9:64 10.1186/1471-2296-9-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjerrum L, Grinsted P, Søgaard P. Detection of bacteriuria by microscopy and dipslide culture in general practice. Eur J Gen Pract 2001;7:55–8. 10.3109/13814780109048788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjerrum L, Grinsted P, Hyltoft Petersen P, et al. Validity of susceptibility testing of uropathogenic bacteria in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:821–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aspevall O, Hallander H, Gant V, et al. European guidelines for urinalysis: a collaborative document produced by European clinical microbiologists and clinical chemists under ECLM in collaboration with ESCMID. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2000;60:1–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knottnerus BJ, Geerlings SE, Moll van Charante EP, et al. Women with symptoms of uncomplicated urinary tract infection are often willing to delay antibiotic treatment: a prospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:71 10.1186/1471-2296-14-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blom M, Sørensen TL, Espersen F, et al. Validation of FLEXICULT SSI-Urinary Kit for use in the primary health care setting. Scand J Infect Dis 2002;34:430–5. 10.1080/00365540110080601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statens Serum Institut. National Veterinary Institute TU of D, National Food Institute TU of D. DANMAP 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holm A, Cordoba G, Sørensen TM, et al. Point of care susceptibility testing in primary care - does it lead to a more appropriate prescription of antibiotics in patients with uncomplicated urinary tract infections? Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:106 10.1186/s12875-015-0322-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm A, Cordoba G, Siersma V, et al. Development and validation of a condition-specific diary to measure severity, bothersomeness and impact on daily activities for patients with acute urinary tract infection in primary care. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:57 10.1186/s12955-017-0629-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statens Serum Institut. National Food Institute Technical University of Denmark, National Veterinary Institute Technical University of Denmark. DANMAP 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodger M, Ramsay T, Fergusson D. Diagnostic randomized controlled trials: the final frontier. Trials 2012;13:137 10.1186/1745-6215-13-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy AG. Evaluating diagnostic tests. J Eval Clin Pract 2016;22:575–9. 10.1111/jep.12541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossuyt PMM, Lijmer JG, Mol BWJ. Randomised comparisons of medical tests: sometimes invalid, not always efficient. The Lancet 2000;356:1844–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03246-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holm A, Cordoba G, Sørensen TM, et al. Clinical accuracy of point-of-care urine culture in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 2017;35:170–7. 10.1080/02813432.2017.1333304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little P, Moore MV, Turner S, et al. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c199–6. 10.1136/bmj.c199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guardabassi L, Courvalin P. Modes of antimicrobial action and mechanisms of bacterial resistance Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria of Animal Origin, 2006:1–17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018028supp001.pdf (147.5KB, pdf)