Abstract

Objective

To systematically search for research about the effectiveness of mandatory reporting of child maltreatment and to synthesise qualitative research that explores mandated reporters’ (MRs) experiences with reporting.

Design

As no studies assessing the effectiveness of mandatory reporting were retrieved from our systematic search, we conducted a meta-synthesis of retrieved qualitative research. Searches in Medline (Ovid), Embase, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Sociological Abstracts, Education Resources Information Center, Criminal Justice Abstracts and Cochrane Library yielded over 6000 citations, which were deduplicated and then screened by two independent reviewers. English-language, primary qualitative studies that investigated MRs’ experiences with reporting of child maltreatment were included. Critical appraisal involved a modified checklist from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme and qualitative meta-synthesis was used to combine results from the primary studies.

Setting

All healthcare and social-service settings implicated by mandatory reporting laws were included. Included studies crossed nine high-income countries (USA, Australia, Sweden, Taiwan, Canada, Norway, Finland, Israel and Cyprus) and three middle-income countries (South Africa, Brazil and El Salvador). Participants: The studies represent the views of 1088 MRs.

Outcomes

Factors that influence MRs’ decision to report and MRs’ views towards and experiences with mandatory reporting of child maltreatment.

Results

Forty-four articles reporting 42 studies were included. Findings indicate that MRs struggle to identify and respond to less overt forms of child maltreatment. While some articles (14%) described positive experiences MRs had with the reporting process, negative experiences were reported in 73% of articles and included accounts of harm to therapeutic relationships and child death following removal from their family of origin.

Conclusions

The findings of this meta-synthesis suggest that there are many potentially harmful experiences associated with mandatory reporting and that research on the effectiveness of this process is urgently needed.

Keywords: child protection, medical law

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the most comprehensive review to date of mandatory reporting of child maltreatment, focusing on mandated reporters’ (MRs) experiences with reporting.

Although a systematic search was conducted, little information about mandatory reporting from low- and middle-income countries was retrieved.

Critical appraisal of included articles followed an established checklist and reporting of synthesis findings was done according to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative research statement.

This meta-synthesis used an established method for synthesising study findings that enabled the creation of recommendations for MRs relating to the reporting process

Introduction

Global estimates of child maltreatment indicate that nearly a quarter of adults (22.6%) have suffered childhood physical abuse; over a third of adults (36.3%) have suffered childhood emotional abuse; 16.3% of adults have suffered childhood neglect and 18% of women and 7.6% of men, respectively, have suffered childhood sexual abuse.1–3 These estimates vary across countries. For example, according to 2015 US child protective services (CPS) reports, 63.4% of reported children experienced neglect.4 Given the high prevalence of child maltreatment and its potentially serious, long-term health and social consequences,5–8 many countries have taken steps to prevent child maltreatment and reduce its associated impairment, including through the introduction of mandatory reporting.

Mandatory reporting law, in the context of child maltreatment, “is a specific kind of legislative enactment which imposes a duty on a specified group or groups of persons outside the family to report suspected cases of designated types of child maltreatment to child welfare agencies”.9 The USA enacted the first mandatory reporting laws in 1963.10 11 These laws were more narrowly conceived, requiring certain mandated professions to report ‘severe’ or ‘significant’ physical abuse by parents or caregivers. Over time, legislation has expanded in the USA and has been replicated in other countries. Across jurisdictions, mandatory reporting can include other forms of maltreatment (notably physical, sexual and emotional abuse, neglect, children’s exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) and prenatal exposure to drug abuse), reporting by more than mandated professionals (eg, by all citizens), reporting abuse perpetrated by non-caregivers and reporting beyond ‘severe’ or ‘significant’ abuse.12

Some information about the international context of mandatory reporting is available, but in general little information about this process is available from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (see online supplementary file 1). Furthermore, while we began this project with the intent of doing a systematic review of studies of effectiveness about mandatory reporting, we were unable to find any studies that could be used for this purpose (ie, no prospective controlled trials, cohort studies or case–control studies assessing the effectiveness of mandatory reporting in relation to child outcomes were retrieved from our systematic search). Instead, we found that while there are a handful of prospective studies assessing particular outcomes of mandatory reporting,13 14 most of the research discussing its impact relies on retrospective analysis of CPS reports15–18 or is related to mandated reporters’ (MRs), children’s and caregivers’ perceptions about reporting, as discussed in surveys,19–27 qualitative literature28–30 or case reports31–33 (qualitative literature is summarised in this meta-synthesis). Given the paucity of data on effectiveness of mandatory reporting, the purpose of this meta-synthesis is to summarise qualitative research about MRs’ experiences with reporting. A companion paper titled, A meta-synthesis of children’s and caregivers’ perceptions of mandatory reporting of child maltreatment (in preparation), will address caregivers’ and children’s experiences with mandatory reporting.

bmjopen-2016-013942supp001.pdf (596.1KB, pdf)

Methods

Various methods for synthesising qualitative literature exist depending on the purpose of the review34 or the philosophical35 or epistemological36 stance of the researcher. As there is no standard way to summarise qualitative literature, for this meta-synthesis we follow the methods of Feder and colleagues,37 whose work builds on Noblit and Hare’s (43) approach to meta-ethnography. Meta-ethnography does not offer suggestions for sampling or appraising articles and at times can be criticised for lack of transparency.34 A benefit of Feder and colleagues’37 method is that they conducted a systematic search of qualitative studies with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, thus enhancing the transparency of their study selection process. While the benefit of appraising qualitative research is still debated,38 Feder and colleagues’ approach to appraising qualitative literature prioritises studies that are ranked as of higher quality, which supports increasing recommendations to consider study quality, but also does not inappropriately exclude so-called lower quality studies that make ‘surface mistakes’ that would not otherwise invalidate their study findings.34 Finally, like Noblit and Hare’s (43) work, Feder et al’s37 approach to synthesising qualitative literature allows for the inductive creation of a set of higher order constructs (third-order constructs, discussed below) that reflect concepts identified in individual studies but also extends beyond them. While the quantification of qualitative work has been criticised, in this study, individual concepts are ‘counted’ to let the reader decide about the relative importance of the themes. We suggest that themes that appear at a lower frequency are not necessarily less important (eg, one account of harm to a child is significant and must be considered) but rather that this theme was less of a focus for MRs and study authors. For example, the theme of ‘cultural competence’ is not discussed by as many MRs as compared with all of the various factors that impact their decision to report, which is partially explained by the fact that 11 (25%) of included articles set out specifically to investigate factors that impact MRs’ decision to report. The results of this meta-synthesis are reported according to the PRISMA checklist and Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative (ENTREQ) research statement35 (see online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2016-013942supp002.pdf (320.8KB, pdf)

Search strategy

The systematic search was conducted by an information professional (JRM). Index terms and keywords related to mandatory reporting (eg, ‘mandatory reporting’, ‘mandated reporters’, ‘duty to report’, ‘failure to report’) and child abuse (broadly defined, including, but not limited to terms for child welfare, physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, sexual abuse/exploitation and children’s exposure to IPV) were used in the following databases from database inception to 3 November 2015: Medline (1947-), Embase (1947-), PsycINFO (1806-), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (1981-), Criminal Justice Abstracts (1968-), Education Resources Information Center (1966-), Sociological Abstracts (1952-) and Cochrane Libraries (see online supplementary file 3 for example search strategy). Forward and backward citation chaining was conducted to complement the search. All articles identified by our database searches were screened by two independent reviewers (JRM and AA) at the title and abstract level. At the level of title and abstract screening, an article suggested for inclusion by one screener was sufficient to put it forward to full-text review. Full-text articles were screened for relevance and put forward for consideration by one author (JRM); relevance for inclusion was confirmed by a second author (MK), with discrepancies being resolved by consensus.

bmjopen-2016-013942supp003.pdf (188.2KB, pdf)

Study selection criteria

Our inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) primary studies that used a qualitative design; (2) published articles; (3) investigations of MRs’ experiences with mandatory reporting of child maltreatment, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, exposure to IPV, prenatal exposure to maternal drug abuse or child sex trafficking; (4) presence of direct quotes from the participants to facilitate the formulation of the results and (5) English-language articles only. Excluded studies include (1) all non-qualitative designs, including surveys with open-response options; (2) studies that did not examine mandatory reporting in the context of child maltreatment (eg, mandatory reporting for elder abuse or IPV only) and (3) qualitative methods that did not lend themselves to direct quotes from participants (eg, forensic interviews).

Data analysis

Data analysis followed two parallel strands: (1) first and second-order constructs (table 1) were identified in each article and (2) each article was appraised with a modified critical appraisal tool for qualitative literature from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). For data extraction, each article was analysed for the perspectives of MRs (first-order constructs) and the conclusions offered by the author(s) of the article (second-order constructs). For first-order constructs, only direct quotes from participants (and any clarifying text provided by the study author) found in the Results sections of included articles were considered for analysis. For second-order constructs, only study author recommendations (often worded as ‘should’ or ‘ought’ statements and found in the Discussion of the article) were considered for analysis.

Table 1.

First, second and third-order constructs

| Construct order | Definition |

| First-order constructs | First-order constructs represent the experiences and understandings of mandated reporters with respect to mandatory reporting processes |

| Second-order constructs | Second-order constructs represent the conclusions or interpretations of the article author(s) who reported the study findings—some of these interpretations were inferred from the author’s recommendations. |

| Third-order constructs | Views and interpretations of the meta-synthesis team |

Two reviewers (JRM and MK) independently placed the primary data from each study and its corresponding code into an Excel file, and these files were compared for consistency (JRM). After reviewing discrepancies across Excel files, one author (JRM) developed a master list of codes, and after discussion with a second author (MK) (where both authors reviewed all codes and corresponding data together), this list of codes was further modified. Any discrepancies identified by the two authors were resolved by a third researcher (HLM). After this point, one author (JRM) went back through and recoded all data in the excel file according to the master list of codes and a second author reviewed all recoding (MK). Readers are able to view this final Excel file, which includes all extracted data, codes (including master list of codes) and overall quality rating of included articles. Final conclusions (third-order constructs (table 1)) were all double checked (JRM) to ensure that they were supported by articles that ranked highly on the quality appraisal forms.

For critical appraisal, a modified appraisal tool from CASP was used to assess the quality of each article (see online supplementary file 4). Two independent authors (JRM and MK) appraised each article to assess if it addressed each CASP question (yes/no/unsure) and came to consensus about the final score for each article. Only the total CASP scores were considered, and studies were not excluded for poor study design, as (1) according to our inclusion criteria, we only included articles with full quotes from MRs, (2) we coded all MRs’ quotes as first-order constructs and (3) we felt that the exclusion of any articles could exclude a valuable quote/perspective from an MR and that this exclusion could impact the meta-synthesis findings.

bmjopen-2016-013942supp004.pdf (503.6KB, pdf)

Data coding for this meta-synthesis was primarily inductive. Data analysis focused on identifying (1) first-order and second-order constructs that appeared across studies (repeating themes); (2) first-order or second-order constructs that were conflicting across studies or within studies and (3) unfounded second-order constructs or researchers’ conclusions or interpretations that were not supported by quotes from participants. First and second-order constructs that appeared across studies were re-examined to develop the third-order constructs or the conclusions of this meta-synthesis. Specifically, one author (JRM) identified third-order constructs that addressed strategies to improve MRs’ experiences with the reporting process—especially when these themes were supported by strategies offered by MRs in first-order constructs—and these themes were, per Feder et al,37 reworded as recommendations. For example, the recommendation that MRs should ‘Be aware of jurisdiction-specific legislation on reportable child maltreatment’ combines a second-order construct that suggests MRs need better training about jurisdiction-specific mandatory reporting legislation with the first-order construct in which MRs admitted that they lacked knowledge about mandatory reporting legislation. These third-order constructs were first discussed with the two authors (MK, HLM) involved in developing the first and second-order constructs to ensure they reflected their understanding of the data. Following this, a table that showed a ‘tally’ of which first and second-order constructs were combined to generate each third-order construct (and a brief rationale for combining them) was reviewed by all study authors and a discussion followed. Minor adjustments to the third-order constructs were made after this discussion. The biggest discrepancy across all authors of this meta-synthesis was whether or not we should offer recommendations specific to mandatory reporting at all, given that (1) we did not find any effectiveness data and (2) the qualitative studies suggest many negative experiences with reporting. However, the third-order constructs represent what is found in the included studies that we synthesised (ie, included studies did not recommend against mandatory reporting), and their presentation as recommendations is faithful to the approach used by Feder et al, which we set out to follow, and the experiences of MRs, as summarised in the included articles.

Results

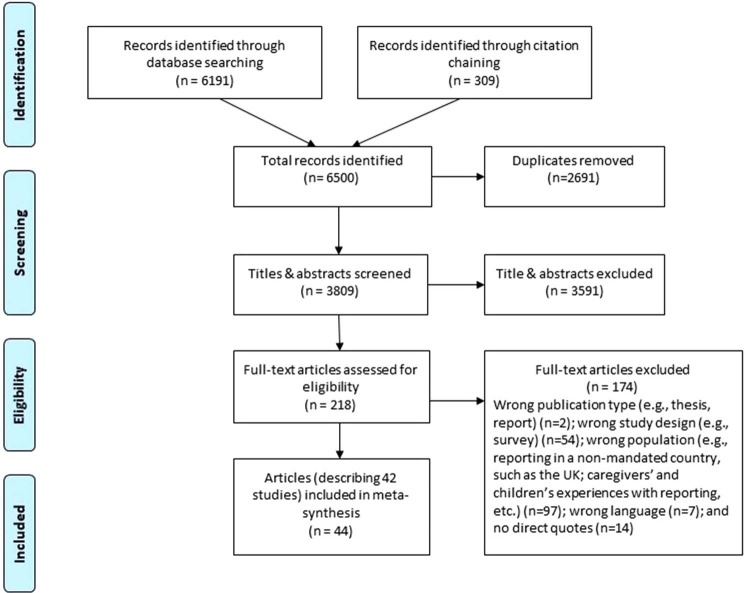

A total of 6500 records were identified and, after deduplication, 3809 titles and abstracts were screened using the screening criteria. After full-text screening of 218 articles, 44 articles (representing 42 studies) were included in this review (see figure 1). Details about participant and study characteristics are available in online supplementary file 5.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

bmjopen-2016-013942supp005.pdf (488.4KB, pdf)

Study characteristics and methodological quality

The methodological quality of the studies varied and the total score percentages for each article (total possible score was 20 ‘yeses’) are reported in table 2. These studies represent the views of 1088 MRs, including 231 physicians, 224 nurses, 168 CPS professionals, 156 teachers, 114 psychologists and therapists, 85 social workers, 19 dentists, 16 domestic violence workers, 16 police officers. This underestimates the number of participants included because it was challenging to determine exact number of participants in some of the studies (including one study with 10 focus groups). MRs’ ages were reported in 25% of studies and ranged from 20 to 60 years of age; their years of experience were reported in just over 50% of the studies and ranged from 6 months to 41 years of experience. Only six articles39–44 discussed any training that MRs received about recognising and responding to child maltreatment; aside from one study42 that was examining the impact of child maltreatment training, it is hard to determine if or how training (or lack of training) influenced MRs’ responses. Over 80% of the articles had been published since the year 2000, with seven articles published between 1981 and 1999. The studies took place in nine high-income countries (USA (15), Australia (6), Sweden (5), Taiwan (5), Canada (2), Israel (2), Norway (1), Finland (1) and Cyprus (1)) and three middle-income countries (South Africa (3), Brazil (2) and El Salvador (1)). Other studies from LMICs were identified45–49 that did not meet all of the inclusion criteria; this limitation of our study is discussed further below.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of studies

| % of total score | 49% and under | 50%–74% | 75% or above |

| Study reference | 41 50 85–94 | 28–30 39 44 51 52 57 75 76 95–106 | 40 42 43 53 107–112 |

MRs’ decisions to report and experiences with reporting (first-order constructs)

Seven first-order constructs (views of MRs) are detailed below; all except construct seven (experiences receiving a report) are supported by articles from the top quartile (see table 2 above). As is shown in table 3, most of the articles (91%) addressed factors that influenced MRs’ decision to report (construct 1). These findings suggest that MRs struggle to identify less overt forms of maltreatment, including ‘mild’ physical abuse, emotional abuse, children’s exposure to IPV and abuse experienced by children with disabilities. MRs also were reluctant to report their suspicions of abuse and preferred to report only when they found physical evidence of abuse, such as physical injuries, bruises, broken bones, caries (and corresponding lack of treatment) or ‘total’ changes in behaviour. Unfortunately, most MRs did not clarify their reporting decisions in relation to specific forms of maltreatment. For example, only five articles28 50–53 discussed decisions to report (including hesitance to report) in relation to sexual abuse, and four of these articles discussed maltreatment of children with disabilities (suggesting particular challenges they faced in reporting maltreatment of children with disabilities).

Table 3.

First-order constructs (views of MRs) and the number (n) and per cent (%) of articles that address each construct

| First-order construct | (n, %) | Description of construct | Illustrative quotes |

| (1) Deciding when to report | n=40, 91% | Factors that influenced MRs’ decision to report, including:

|

“The most obvious (signs) are easy. It’s the ones that are not so obvious, the ones that you have to dig for and explore to get to…those are the hardest ones…those are the ones that just haunt you.”95

“We need more time (than 24 hours) to interact with the child, evaluate the whole thing, and make a decision.”99 “If nothing comes out of it (report to CPS is unsubstantiated)…you’re scared…thinking, I just bothered this family for no reason based on my assumptions.”75 |

| (a) Evidence | n=32, 73% | ||

| (b) Context of reporter | n=28, 64% | ||

| (c) Alternative response | n=19, 43% | ||

| (d) Perceived impact | n=12, 27% | ||

| (e) Consultation | n=9, 20% | ||

| (f) Context of family | n=8, 18% | ||

| (2) Judgements and views towards the reporting process | n=34, 77% | Factors related to MRs’ general satisfaction with the reporting process, including:

|

“Knowing the child protection agency in our area, nothing would come of a report.”57

“It’s pretty much a one way street as far as information goes. I find that really frustrating.”111 |

| (a) Negative | n=33, 75% | ||

| (b) Positive | n=11, 25% | ||

| (3) Experiences with reporting | n=33, 73% | Examples of MRs’ positive or negative experiences with the reporting process, including:

|

“You’ll call and say, ‘I have a such and such child who made an outcry that her uncle rubbed her breasts last night.’ And they’ll be like, ‘Well, was it over the clothes or under the clothes?’…I know that’s all part of their risk assessment and they have to get to the high-priority risk to be able to take a report, but it’s really challenging to hear someone on the other line say, ‘Well, you know, that’s just not bad enough.”101

“She made the student describe the sexual abuse experience again after they returned from the hospital. This is so (emphasised) wrong. The student should not have to experience secondary damage by going through this again and again.”109 |

| (a) Negative | n=32, 74% | ||

| (b) Positive | n=6, 14% | ||

| (4) MRs’ values and knowledge | n=19, 43% | Values and knowledge that informed MRs throughout the reporting process:

|

“Many times, we don’t have adequate knowledge about child abuse and the law. It is not extensively provided to every healthcare provider or to ordinary people. Without the knowledge, it is hard for us to be sensitive about the abuse or to find evidence of child abuse.”39 |

| (5) Strategies for responding to disclosures of maltreatment and reporting | n=16, 36% | Practical strategies used by MRs during the reporting process, including:

|

“My sense was that this child just wanted to know that she was safe and that she could tell someone, so I used that to help, in questioning her, reassuring her that nothing would happen if she told…(When the report was made) I presented it to her as that she wouldn’t get in trouble but that it was a secret that I couldn’t keep, and that it was something that I could help her with…she was very aware of the decision…The child knew what was going on and she felt comfortable with my telling her I was going to make a report.”91 |

| (6) Responsibility | n=15, 34% |

|

“I reported my suspicions to the doctor that was looking after the child and he reported it to the consultant.”76 |

| (7) Experiences receiving a report | n=2, 5% |

|

“So part of the issue for us is because we got all of these mandated reporters and intake has to take the complaint regardless, that’s the problem. It’s that they’re not permitted to say, well that’s not enough information.”97 |

CPS, child protective services; MRs, mandated reporters.

Factors that influenced the decision to report were distinct from the reporters’ judgements and views about mandated reporting (construct 2) and their experiences with reporting (construct 3), as expressed through specific accounts of positive or negative experiences. While six articles (14%) reported positive experiences with the reporting process, 32 articles (73%) mentioned negative experiences with the reporting process, including 13 articles (30%) that offered concerning examples regarding negative child outcomes, such as: when the child was not removed from harm and the abuse continued or intensified; when the child was removed from harm, but the foster care environment was worse than the family-of-origin environment and child death following a report or after being removed from the family of origin.

First-order constructs also addressed MRs’ values and knowledge related to child maltreatment and reporting (construct 4), MRs’ strategies for responding to disclosures of child maltreatment or for reporting (construct 5) and whether or not MRs felt personally responsible for reporting or passed this responsibility to others, such as a supervisor (construct 6). A handful of articles included CPS professionals' experiences with receiving a report (construct 7).

Strategies for supporting MRs (second-order constructs)

All second-order constructs (views of study authors) listed in table 4 below were supported by first-order constructs within the same study; all were also supported by articles from the top quartile of study quality score (see table 2 above). These constructs represent study authors’ suggestions for how MRs could improve their decision-making during the reporting process, including strategies for mitigating negative experiences. The majority of articles (86%) commented on the need for MRs to be trained in how to best identify, respond and report suspected child maltreatment (construct 1). Two other influential themes related to the need for increased consultation between MRs and between MRs and CPS (construct 2) and the need for increased communication among MRs, among MRs, children and families and between MRs and CPS (construct 3). Study authors also emphasised that MRs need to be better supported in their reporting process (construct 4) and that they need clear protocols related to identifying and reporting child maltreatment (construct 5). Some study authors emphasised that child rights and well-being must be prioritised throughout the reporting process (construct 6). A few study authors suggested that MRs’ and CPS’ responses to child maltreatment need to be culturally competent (construct 7) and emphasised that MRs must report suspicions of abuse when this is their legal obligation (construct 8).

Table 4.

Second-order constructs (views of study authors) and the number (n) and per cent (%) of articles that address each construct

| Second-order construct | (n, %) | Description and citations for supporting articles from the top quartile | Illustrative quotes |

| 1. Training and knowledge | n=38, 86% |

|

“All practitioners whose patients include children should avail themselves regularly of educational opportunities to increase their knowledge of the epidemiology and evaluation of child abuse and neglect.”112

“Professionals and authorities should have increased awareness of the legislation and their duties in all forms of violence.”104 “Good guidelines are important, but missing guidelines must not be an excuse not to care.”107 “Reporting, a legal requirement, must be separated from responding, which is a moral duty.”99 |

| 2. Consultation | n=23, 52% |

|

“Another important finding from the study is the urgent need to improve systematic collaboration and a trustful relationship with CPS.”43

“An important resource to develop in an effort to improve child abuse and neglect detection and reporting may be the identification and ongoing support of child abuse and neglect content experts within nonpediatric and nonacademic hospital.”75 |

| 3. Communication | n=21, 47% |

|

“Forewarning is critical for ensuring that clients do not feel deceived into thinking that superior levels of confidentiality exist.108

“Mandated professionals require feedback from child protection agencies.”76 |

| 4. Support | n=12, 27% |

|

“Employing bodies are encouraged to provide a suitable support mechanism to decrease the stress and anxiety of individuals who are emotionally traumatised by the process of mandatory reporting.”76 |

| 5. Structural concerns | n=7, 16% |

|

“It is recommended that a formalised national framework for reporting and feedback be established, which incorporates exemplar cases to demonstrate processes and outcomes which will positively influence future decision-making of mandated professionals.”76 |

| 6. Child rights & well-being | n=6, 14% |

|

“If the intention is for children to have the full status of victim, the focus should not only be on reporting but also on the responses following reporting.”104 |

| 7. Cultural competence | n=4, 9% |

|

“People’s preference for traditional ways of dealing with problem should not be taken lightly, especially as any dismissal of it could be taken as constituting a lack of trust and understanding by the establishment of the current African ways of dealing with abuse.”53 |

| 8. Evidence | n=4, 9% |

|

“Physicians and other healthcare workers are legally required to report cases if they have reasonable suspicion of child abuse.”92 |

CPS, child protective services; MRs, mandated reporters.

These second-order constructs show that MRs need better support at all social–ecological levels: (1) personally, in terms of better training, including skills to identify and respond to child maltreatment, as well as skills for stress and coping management; (2) interpersonally, in terms of better opportunities for dialogue among colleagues about child maltreatment generally, as well as specific cases; (3) organisationally, in terms of more support for the time it takes to report (and the potential ‘costs’ to other patients when taking this time), safeguards for MRs’ personal safety when reporting and access to staff experts in child maltreatment; (4) in the community, especially in terms of better feedback about reported cases from CPS and in general better dialogue between different agencies involved in the reporting process and (5) nationally, in terms of national protocols about identifying, responding to and reporting child maltreatment.

Apparent contradictions

All of the apparent contradictions found within the studies (or constructs that conflicted within or across studies) are examples of correlates of reporting that have been discussed previously in the literature (eg, MRs’ decisions to report should or should not be influenced by the context of the family, the level of evidence available, the context of the reporter or the perceived impact of reporting on the child or family; MRs should or should not report children’s exposure to IPV or corporal punishment; MRs should or should not intervene with the family instead of reporting; the MR who identifies maltreatment should report it or refer it to a senior personnel). The solutions to these contradictions are more straightforward to resolve legally but less so ethically. For example, in cases where MRs suspect that harm may come to a child from the reporting process (based on their experience or their expert judgement), they are still required to report legally (when the type and severity of child maltreatment falls within their jurisdiction’s legislation).

Recommendations for MRs (third-order constructs)

The first-order constructs draw attention to several negative experiences MRs had with the reporting process, as well as a number of factors that influenced their decision to report. The second-order constructs summarise some institutional and cross-disciplinary responses to these concerns (offered by study authors), such as the need for increased feedback from CPS about reported cases, the need for clear protocols for identifying child maltreatment and reporting it and the need for MRs to be better supported in their reporting process. Most of the second-order constructs, however, discuss how MRs’ negative experiences with the reporting process can be addressed through increased training and better communication or consultation among MRs, their colleagues and CPS. The third-order constructs found in table 5 represent study authors’ interpretation, across the studies, of MRs’ and study authors’ strategies for mitigating negative experiences with the reporting process, which includes the level of knowledge about child maltreatment that is required by all MRs. Restriction of the analysis to studies in the top quartile of quality ratings did not change these third-order constructs.

Table 5.

Third-order constructs in terms of recommendations to MRs

| When | What/How |

| Before identification or disclosure of child maltreatment |

|

| At the beginning of a relationship with a child or family |

|

| Immediate response to disclosure |

|

| Debriefing after report |

|

CPS, child protective services; MRs, mandated reporters.

Discussion

While our search retrieved no evidence about the effectiveness of mandatory reporting, and qualitative research cannot be mistaken for evaluation of effectiveness, findings from this review raise important questions about the effects of mandatory reporting by drawing on studies reporting the experiences of MRs across nine high-income and three middle-income countries. While some MRs have had positive experiences with reporting, the negative experiences reported in the individual studies are very concerning, especially those related to child outcomes. Some of these include accounts of children being revictimised by the reporting process, children whose abuse intensified after a report was filed, foster care environments that were perceived to be worse than family-of-origin environments and reports of child death after CPS intervention. Whether or not these negative experiences are reflective of national or international experiences must be assessed. Studies addressing MRs’ attitudes towards reporting address perceptions of negative experiences but are not able to address child-specific outcomes.54–56 For example, Flaherty and colleagues’54 US national survey of paediatricians found that 56% of physicians experienced negative consequences from reporting, including 40% who lost patients after reporting and 2% who were sued for malpractice. Some of these concerns are likely to be especially salient for MRs in countries where child protection systems are not well developed or do not function properly. MRs may have real concerns that reporting cases of child maltreatment to poorly trained or poorly resourced service providers could lead to adverse outcomes for children (see, for example, the concerns raised by Devries and colleagues46 about the very poor response of local services to children in Uganda). Particularly in these contexts, further research on the harms and benefits of mandatory reporting is needed.

Given that negative experiences with reporting discussed in this meta-synthesis spanned decades and nine high-income and three middle-income countries, it is not surprising that some authors have suggested that the interface between MRs and CPS agencies ‘requires renewed attention, in terms of both research and programming’.57 We were unable to find any high-quality research studies suggesting that mandatory reporting and associated responses do more good than harm. The lack of evidence about the effectiveness of mandatory reporting has been noted by others, including the WHO.58 More research addressing child-specific outcomes is needed on 1) alternative approaches to mandatory reporting as well as 2) alternative responses to investigation following mandatory reporting (such as differential response; see online supplementary file 1).

Researchers citing the benefits of mandatory reporting note that mandatory reporting laws are an “essential means of asserting that a society is willing to be informed of child abuse and to take steps to respond to it”11; they also note that mandatory reporting laws have resulted in the identification of more cases of child maltreatment59–61 and an increase in reporting from reluctant reporter groups.62 63 It has been argued by some authors64 65 that identification is not a sufficient justification given the problems with the mandatory reporting process; as described in this meta-synthesis, negative experiences seem to involve the reporting process itself and the associated responses (or lack of response). A key issue is the number of children identified by MRs who receive either no services or of greater concern—inappropriate, ineffective or harmful responses. MRs’ discussions of ineffective responses seem to be related most closely to their reports of ‘mild’ physical violence, neglect, emotional abuse or children’s exposure to IPV, which may lend credence to the suggestion that mandatory reporting is most appropriate for cases of severe abuse and neglect.11 More research about the effectiveness of mandatory reporting across abuse types and severity, as well as associated responses and strategies for mitigating harm (including strategies for including children and family in the reporting process), is urgently needed.

Implications for clinicians and policy-makers

Much of the research included in this meta-synthesis did not question the need for mandatory reporting (as many of the studies aimed to address MRs’ decision-making process with regards to reporting); instead, it included studies that addressed MRs’ negative experiences and reluctance to report with suggestions about the need for increased support, training, consultation and communication. The third-order constructs (final conclusions) of this study therefore offer recommendations for how MRs can mitigate negative experiences with the reporting process.

Analysis of recommendations by study authors suggests that MRs need better support for the reporting process at many levels: personally, interpersonally, institutionally, in the community and nationally. Personal support for reporters can include training or support for secondary traumatic stress—which many healthcare professionals experience—through, for example, strategies for debriefing.66–68 Emerging work is examining the methods by which health and social service providers can be trained to recognise and respond to child maltreatment disclosures and suspicions of child maltreatment (for example, see 69–71). Given that the evaluation of these training programmes falls outside the scope of this review, and that mandatory reporting is but one of many components of appropriate recognition of and response to children exposed to maltreatment, further work and evaluation is needed to understand the extent to which existing training programmes are capable of improving MRs’ recognition and response to children exposed to maltreatment or if further specialised training is needed. Among studies of training programmes for mandatory reporting with controlled designs, Kenny72 argues that Alvarez and colleagues’73 training programme shows the most promise. The components of the training programme, discussed further by Donohue et al,69 include discussions about identifying child maltreatment, reporting requirements and procedures, strategies for involving caregivers in the reporting process and information about consultation with colleagues and CPS—all identified as important components of training in this review. Whether or not the training programmes can be successfully modified to address the training needs of different countries and multidisciplinary trainees has yet to be assessed.

Interpersonal support can include increased opportunity for communication and teamwork between interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary colleagues through, for example, interdisciplinary training42 or multidisciplinary conferences.74 Relatedly, community support can include increased communication and collaboration between reporting professionals; the need for increased feedback from CPS about reported cases is also important.54–56 75 76 Poor communication or collaboration between CPS and MRs has long been cited as an area for much needed improvement.74 77–80 How exactly to improve collaboration, however, is complex and under-researched. As Winkworth and White81 argued in relation to Australian initiatives to increase collaboration between child protection, family relationship and family support service systems, “So ubiquitous is reference to collaboration in policy documents that it is in danger of being ignored altogether by service deliverers who are not clear about its rationale, how it is built, or its real value”. Finally, national support necessitates national protocols about identifying, responding to and reporting abuse, as well as increased clarity around specific reporting requirements (including increased clarity around national or jurisdictional reporting legislation). Whether or not national protocols improve the reporting process for MRs or help to improve child outcomes would need to be tested.82–84

Strengths, limitations and future research

The strengths of our review include a systematic search to inform the meta-synthesis; the use of clear a priori study inclusion and exclusion criteria; use of an established study appraisal checklist and transparent and reproducible methods for analysis. This review focused on MRs’ direct experiences with, or views about, the mandatory reporting process and as such does not reflect complete findings about (1) appropriate MR responses to the disclosures or identification of child maltreatment; (2) CPS workers’ experiences substantiating reports; (3) children’s and caregivers’ experiences with mandatory reporting and (4) professionals’ experiences with reporting in a non-mandated context (such as the UK). Reviews on these topics would be complementary to the findings of this review. While only English-language studies were included and only a handful of included articles discussed reporting processes in LMICs, the limited availability of research from LMICs suggests an even greater need to invest in research in these settings. Research about voluntary or policy-based reporting processes, as well as responses to mandatory reporting, may provide more information about reporting process from LMICs.

Conclusion

Mandatory reporting of child maltreatment has been variously implemented across jurisdictions and high-quality research on the effectiveness of this process is severely lacking. While our search retrieved no evidence about the effectiveness of mandatory reporting, through this meta-synthesis of MRs’ experiences with reporting, we have summarised many accounts of harm associated with reporting. Along with focusing on approaches to improve mandatory reporting, the field needs to address whether or not mandatory reporting actually improves children’s health outcomes through research that is sensitive to both severe and less overt forms of maltreatment. Our findings in no way imply that the recognition and response to children exposed to maltreatment is not a significant public health concern that requires coordinated responses. Rather, it implies that we must work to ensure that all of our methods for recognising and responding to children exposed to maltreatment demonstrate that they benefit children’s safety and well-being and do no additional harm.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualisation: HLM, KD, MC, JRMT, JCDM; Analysed the data: JRMT, MK, AA, HLM; Writing–original draft preparation: JRMT; Writing–review and editing: JRMT, MK, KD, MC, JCDM, CNW, HLM; ICMJE criteria for authorship read: JRMT, MK, KD, MC, JCDM, CNW, AA, HLM; Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: JRMT, MK, KD, MC, JCDM, CNW, AA, HLM.

Funding: HLM and CNW receive funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Institute of Gender and Health (IGH) and Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addictions (INMHA) to the PreVAiL Research Network (a CIHR Center for Research Development in Gender, Mental Health and Violence across the Lifespan—www.PreVAiLResearch.ca). HLM holds the Chedoke Health Chair in Child Psychiatry at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. JRMT is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Violence Evidence Guidance Action (VEGA). MK is supported by Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Women’s Health Scholar Post-Doctoral Fellowship Award. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.6d159.

References

- 1.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, et al. Cultural-geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. Int J Psychol 2013;48:81–94. 10.1080/00207594.2012.697165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. The neglect of child neglect: a meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;48:345–55. 10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. The neglect of child neglect: a meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:345–55. 10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U. S Department of Health Human Services AfCF, Administration on Children Youth Families, Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 20152017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;256:174–86. 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Grashow R, et al. Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 2014;59:359–72. 10.1007/s00038-013-0519-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacMillan HL, Jamieson E, Wathen CN, et al. Development of a policy-relevant child maltreatment research strategy. Milbank Q 2007;85:337–74. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00490.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masson M, Bussières EL, East-Richard C, et al. Neuropsychological Profile of Children, Adolescents and Adults Experiencing Maltreatment: A Meta-analysis. Clin Neuropsychol 2015;29:573–94. 10.1080/13854046.2015.1061057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathews B. Developing countries and the potential of mandatory reporting laws to identify severe child abuse and neglect Deb S, ed Child Safety, Welfare and Well-being: Issues and challenges. New York, NY: Springer, 2016:335–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Humane A. National analysis of official child abuse and neglect reporting. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews B. Mandatory Reporting Laws: Their Origin, Nature, and Development over Time : Mathews B, Bross DC, Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse and Marginalised Families. Aurora: CO: Springer, 2015:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathews B, Kenny MC. Mandatory reporting legislation in the United States, Canada, and Australia: a cross-jurisdictional review of key features, differences, and issues. Child Maltreat 2008;13:50–63. 10.1177/1077559507310613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson H, Levine M. Psychotherapy and mandated reporting of child abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1989;59:246–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knight ED, Smith JB, Dubowitz H, et al. Reporting participants in research studies to Child Protective Services: limited risk to attrition. Child Maltreat 2006;11:257–62. 10.1177/1077559505285786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krase KS. Child maltreatment reporting by educational personnel: Implications for racial disproportionality in the child welfare system. Children & Schools 2015;37:88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krase KS, DeLong-Hamilton TA. Comparing reports of suspected child maltreatment in states with and without Universal Mandated Reporting. Children and Youth Services Review 2015;50:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steen JA, Duran L. Entryway into the child protection system: the impacts of child maltreatment reporting policies and reporting system structures. Child Abuse Negl 2014;38:868–74. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palusci VJ, Vandervort FE. Universal reporting laws and child maltreatment report rates in large U.S. counties. Children and Youth Services Review 2014;38:20–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawson D, Niven B. The impact of mandatory reporting legislation on New Zealand secondary school students' attitudes towards disclosure of child abuse. International Journal of Children’s Rights 2015;23:491–528. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tufford L. Repairing alliance ruptures in the mandatory reporting of child maltreatment: Perspectives from social work. Families in Society 2014;95:115–21. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steen JA. Attitudes of domestic violence shelter workers toward mandated reporter laws: a study of policy support and policy impact. Journal of Policy Practice 2009;833:2113p. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strozier M, Brown R, Fennell M, et al. Experiences of mandated reporting among family therapists: a qualitative analysis. Contemp Fam Ther 2005;27:193–212. 10.1007/s10591-005-4039-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg KL, Levine M, Doueck HJ. Effects of legally mandated child-abuse reports on the therapeutic relationship: a survey of psychotherapists. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1997;67:112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinstein B, Levine M, Kogan N, et al. Therapist reporting of suspected child abuse and maltreatment: factors associated with outcome. Am J Psychother 2001;55:219–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renninger SM, Veach PM, Bagdade P. Psychologists' knowledge, opinions, and decision-making processes regarding child abuse and neglect reporting laws. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2002;33:19–23. 10.1037/0735-7028.33.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theodore AD, Runyan DK. A survey of pediatricians' attitudes and experiences with court in cases of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl 2006;30:1353–63. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cairns AM, Mok JY, Welbury RR. The dental practitioner and child protection in Scotland. Br Dent J 2005;199:517–20. discussion 12; quiz 30-1 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deisz R, Doueck HJ, George N. Reasonable cause: a qualitative study of mandated reporting. Child Abuse Negl 1996;20:275–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shalhoub-Kevorkian N. Disclosure of child abuse in conflict areas. Violence Against Women 2005;11:1263–91. 10.1177/1077801205280180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kvist T, Wickström A, Miglis I, et al. The dilemma of reporting suspicions of child maltreatment in pediatric dentistry. Eur J Oral Sci 2014;122:332–8. 10.1111/eos.12143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bean H, Softas-Nall L, Mahoney M. Reflections on mandated reporting and challenges in the therapeutic relationship: A case study with systemic implications. The Family Journal 2011;19:286–90. 10.1177/1066480711407444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oz S, Balshan D. Mandatory reporting of childhood sexual abuse in Israel: what happens after the report? J Child Sex Abus 2007;16:1–22. 10.1300/J070v16n04_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tufford L, Mishna F, Black T. Mandatory reporting and child exposure to domestic violence: Issues regarding the therapeutic alliance with couples. Clinical Social Work Journal 2010;38:426–34. 10.1007/s10615-009-0234-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53. 10.1177/135581960501000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:59 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feder GS, Hutson M, Ramsay J, et al. Women exposed to intimate partner violence: expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: a meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:22–37. 10.1001/archinte.166.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dixon-Woods M, Shaw RL, Agarwal S, et al. The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:223–5. 10.1136/qhc.13.3.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng JY, Jezewski MA, Hsu TW. The meaning of child abuse for nurses in Taiwan. J Transcult Nurs 2005;16:142–9. 10.1177/1043659604273551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng J-Y, Chen S-J, Wilk NC, et al. Kindergarten teachers' experience of reporting child abuse in Taiwan: Dancing on the edge. Children and Youth Services Review 2009;31:405–9. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurtado A, Katz C, Ciro D, et al. Teachers' knowledge, attitudes and experience in sexual abuse prevention education in El Salvador. Glob Public Health 2013;8:1075–86. 10.1080/17441692.2013.839729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itzhaky H, Zanbar L. In the front line: the impact of specialist training for hospital physicians in children at risk on their collaboration with social workers. Soc Work Health Care 2014;53:617–39. 10.1080/00981389.2014.921267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraft LE, Eriksson UB. The School Nurse’s Ability to Detect and Support Abused Children: A Trust-Creating Process. J Sch Nurs 2015;31:353–62. 10.1177/1059840514550483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zannettino L, McLaren H. Domestic violence and child protection: towards a collaborative approach across the two service sectors. Child Fam Soc Work 2014;19:421–31. 10.1111/cfs.12037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borimnejad L, Khoshnavay Fomani F. Child abuse reporting barriers: Iranian nurses' experiences. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2015;17:e22296 10.5812/ircmj.22296v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devries KM, Child JC, Elbourne D, et al. "I never expected that it would happen, coming to ask me such questions":Ethical aspects of asking children about violence in resource poor settings. Trials 2015;16:1–12. 10.1186/s13063-015-1004-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lobato GR, Moraes CL, Nascimento MC. [Challenges for dealing with cases of domestic violence against children and adolescents through the family health program in a medium-sized city in Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica 2012;28:1749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silva PA, Lunardi VL, Silva MRS, et al. Reporting family violence against children and adolescents in the perception of health professionals. Ciencia, Cuidado e Saude 2009;862:567p. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Armenta MF, Verdugo VC, del Refugio Meza M. Discretion in the detection and reporting of child abuse in health institutions in Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Psicologia 1999;16:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mallén A. ‘It’s like piecing together small pieces of a puzzle’. Difficulties in reporting abuse and neglect of disabled children to the social services. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention 2011;12:45–62. 10.1080/14043858.2011.561622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liou W-Y, Chen L-Y. Special Education Teachers’ Perspective on Mandatory Reporting of Sexual Victimization of Students in Taiwan. Sex Disabil 2016:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phasha TN. Influences on under reporting of sexual abuse of teenagers with intellectual disability: Results and implications of a South African study. Journal of Psychology in Africa 2013;23:625–9. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phasha N. Responses to situations of sexual abuse involving teenagers with intellectual disability. Sex Disabil 2009;27:187–203. 10.1007/s11195-009-9134-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flaherty EG, Sege R, Price LL, et al. Pediatrician characteristics associated with child abuse identification and reporting: results from a national survey of pediatricians. Child Maltreat 2006;11:361–9. 10.1177/1077559506292287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flaherty EG, Sege R, Binns HJ, et al. Health care providers' experience reporting child abuse in the primary care setting. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vulliamy AP, Sullivan R. Reporting child abuse: pediatricians' experiences with the child protection system. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:1461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones R, Flaherty EG, Binns HJ, et al. Clinicians' description of factors influencing their reporting of suspected child abuse: report of the Child Abuse Reporting Experience Study Research Group. Pediatrics 2008;122:259–66. 10.1542/peds.2007-2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Health O. International Society for Prevention of Child A, Neglect. Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamond DA. The impact of mandatory reporting legislation on reporting behavior. Child Abuse Negl 1989;13:471–80. 10.1016/0145-2134(89)90051-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Besharov DJ. Recognizing child abuse: a guide for the concerned. New York: Toronto: Free Press; Collier Macmillan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathews B, Lee XJ, Norman RE. Impact of a new mandatory reporting law on reporting and identification of child sexual abuse: a seven year time trend analysis. Child Abuse Negl 2016;56:62–79. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Webberley HR. Child maltreatment reporting laws: impact on professionals' reporting behaviour. Aust J Soc Issues 1985;20:118–23. 10.1002/j.1839-4655.1985.tb00795.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shamley D, Kingston L, Smith M. Health professionals' knowledge of and attitudes towards child abuse reporting laws and case management. Australian Child and Family Welfare 1984;9:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Melton GB. Mandated reporting: a policy without reason. Child Abuse Negl 2005;29:9–18. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Worley NK, Melton GB. Mandated reporting laws and child maltreatment: the evolution of a flawed policy response In: Krugman RD, Korbin JE, eds C. Henry Kempe: A 50 Year Legacy to the Field of Child Abuse and Neglect: Springer Netherlands, 2013:103–18. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Healy S, Tyrrell M. Importance of debriefing following critical incidents. Emerg Nurse 2013;20:32–7. 10.7748/en2013.03.20.10.32.s8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Couper K, Salman B, Soar J, et al. Debriefing to improve outcomes from critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1513–23. 10.1007/s00134-013-2951-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith A, Roberts K. Interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder and psychological distress in emergency ambulance personnel: a review of the literature. Emerg Med J 2003;20:75–8. 10.1136/emj.20.1.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Donohue B, Alvarez KM, Schubert KM. An evidence-supported approach to reporting child maltreatment In: Mathews B, Bross DC, eds Mandatory Reporting Laws and the Identification of Severe Child Abuse and Neglect. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2015:347–79. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Donohue B, Carpin K, Alvarez KM, et al. A standardized method of diplomatically and effectively reporting child abuse to state authorities. Behav Modif 2002;26:684–99. 10.1177/014544502236657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.A public health response to family violence. Welcome to the VEGA (Violence, Evidence, Guidance and Action) Project: VEGA. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kenny MC, Abreu RL. Training mental health professionals in child sexual abuse: curricular guidelines. J Child Sex Abus 2015;24:572–91. 10.1080/10538712.2015.1042185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alvarez KM, Donohue B, Carpenter A, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a training method to assist professionals in reporting suspected child maltreatment. Child Maltreat 2010;15:211–8. 10.1177/1077559510365535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Flaherty EG, Sege RD, Hurley TP, et al. Strategies for saving and improving children’s lives: table 1. Pediatrics 2008;122(Supplement 1):S18–S20. 10.1542/peds.2008-0715g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tiyyagura G, Gawel M, Koziel JR, et al. Barriers and facilitators to detecting child abuse and neglect in general emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:447–54. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Francis K, Chapman Y, Sellick K, et al. The decision-making processes adopted by rurally located mandated professionals when child abuse or neglect is suspected. Contemp Nurse 2012;41:58–69. 10.5172/conu.2012.41.1.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goad J. Understanding roles and improving reporting and response relationships across professional boundaries. Pediatrics 2008;122(Supplement 1):S6.2–S9. 10.1542/peds.2008-0715D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Flaherty EG, Sege RD, Hurley TP. Translating child abuse research into action: figure 1. Pediatrics 2008;122(Supplement 1):S1–S5. 10.1542/peds.2008-0715c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Horwath J, Morrison T, Collaboration MT. Collaboration, integration and change in children’s services: critical issues and key ingredients. Child Abuse Negl 2007;31:55–69. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kolko DJ, Herschell AD, Costello AH, et al. Child welfare recommendations to improve mental health services for children who have experienced abuse and neglect: a national perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health 2009;36:50–62. 10.1007/s10488-008-0202-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winkworth G, White M, ‘Safe Australia’s Children. Australia’s Children ‘Safe and Well’?1 Collaborating with purpose across commonwealth family relationship and state child protection systems. Australian Journal of Public Administration 2011;70:1–14. 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2010.00706.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Diderich HM, Pannebakker FD, Dechesne M, et al. Support and monitoring of families after child abuse detection based on parental characteristics at the Emergency Department. Child Care Health Dev 2015;41:194–202. 10.1111/cch.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roberts SC, Zahnd E, Sufrin C, et al. Does adopting a prenatal substance use protocol reduce racial disparities in CPS reporting related to maternal drug use? A California case study. J Perinatol 2015;35:146–50. 10.1038/jp.2014.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berkers G, Biesaart MC, Leeuwenburgh-Pronk WG. [Disciplinary verdicts in cases of child abuse; lessons for paediatricians]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2015;159:A8509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barksdale C. Child abuse reporting: A clinical dilemma? Smith College Studies in Social Work 1989;59:170–82. 10.1080/00377318909516657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.VanBergeijk EO, Sarmiento TL. The consequences of reporting child maltreatment: Are school personnel at risk for secondary Traumatic stress? Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 2006;6:79–98. 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhj003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Muehleman T, Kimmons C. Psychologists' views on child abuse reporting, confidentiality, life, and the law: an exploratory study. Prof Psychol 1981;12:631–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Panayiotopoulos C. Mandatory reporting of domestic violence cases in Cyprus; barriers to the effectiveness of mandatory reporting and issues for future practice. European Journal of Social Work 2011;14:379–402. 10.1080/13691457.2010.490936 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Iossi Silva MA, Carvalho Ferriani M, Silva MAI, Ferriani C. Domestic violence: from the visible to the invisible. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2007;15:275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anderson E, Levine M, Sharma A, et al. Coercive uses of mandatory reporting in therapeutic relationships. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 1993;11:335–45. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Anderson E, Steinberg K, Ferretti L, et al. Consequences and dilemmas in therapeutic relationships with families resulting from mandatory reporting legislation. Law Policy 1992;14(2-3):241–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sege R, Flaherty E, Jones R, et al. To report or not to report: examination of the initial primary care management of suspicious childhood injuries. Acad Pediatr 2011;11:460–6. 10.1016/j.acap.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Waugh F, Bonner M. Domestic violence and child protection: Issues in safety planning. Child Abuse Review 2002;11:282–95. 10.1002/car.758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Giovannoni JM. Unsubstantiated reports: Perspectives of child protection workers. Child & Youth Services 1991;15:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eisbach SS, Driessnack M. Am I sure I want to go down this road? Hesitations in the reporting of child maltreatment by nurses. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2010;15:317–23. 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gallagher-Mackay K. Teachers' Duty to Report Child Abuse and Neglect and the Paradox of Noncompliance: Relational Theory and “Compliance” in the Human Services. Law Policy 2014;36:256–89. 10.1111/lapo.12020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee SJ, Sobeck JL, Djelaj V, et al. When practice and policy collide: Child welfare workers' perceptions of investigation processes. Children and Youth Services Review 2013;35:634–41. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Davidov DM, Jack SM, Frost SS, et al. Mandatory reporting in the context of home visitation programs: intimate partner violence and children’s exposure to intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women 2012;18:595–610. 10.1177/1077801212453278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Feng J-Y, Chen Y-W, Fetzer S, et al. Ethical and legal challenges of mandated child abuse reporters. Children and Youth Services Review 2012;34:276–80. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tite R. How teachers define and respond to child abuse: the distinction between theoretical and reportable cases. Child Abuse Negl 1993;17:591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chanmugam A. A qualitative study of school social workers' clinical and professional relationships when reporting child maltreatment. Children & Schools 2009;31:145–61. 10.1093/cs/31.3.145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tlakale Nareadi Phasha. The Role of the Teacher in Helping Learners Overcome the Negative Impact of Child Sexual Abuse. Sch Psychol Int 2008;29:303–27. 10.1177/0143034308093671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nayda R. Influences on registered nurses' decision-making in cases of suspected child abuse. Child Abuse Review 2002;11:168–78. 10.1002/car.736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ellonen N, Pösö T. Hesitation as a System Response to Children Exposed to Violence. The International Journal of Children’s Rights 2014;22:730–47. 10.1163/15718182-02204001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Svärd V. Hospital social workers' assessment processes for children at risk: positions in and contributions to inter-professional teams. European Journal of Social Work 2014;17:508–22. 10.1080/13691457.2013.806296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.VanBergeijk E, Sarmiento T. On the Border of Disorder: School Personnel’s Experiences Reporting Child Abuse on the U.S.–Mexico Border. Brief Treat Crisis Interv 2005;5:159–85. 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Skarsaune K, Bondas T. Neglected nursing responsibility when suspecting child abuse. Clinical Nursing Studies 2015;4 10.5430/cns.v4n1p24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McLaren H. Exploring the Ethics of Forewarning: Social Workers, Confidentiality and Potential Child Abuse Disclosures. Ethics and Social Welfare 2007;1:22–40. 10.1080/17496530701237159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feng JY, Fetzer S, Chen YW, et al. Multidisciplinary collaboration reporting child abuse: a grounded theory study. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:1483–90. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Angelo M, Prado SI, Cruz AC, et al. Nurses' experiences caring for child victims of domestic violence: a phenomenological analysis. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem 2013;22:585–92. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Land M, Barclay L. Nurses’ contribution to child protection. Neonatal, Paediatric and Child Health Nursing 2008;11:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tingberg B, Bredlöv B, Ygge BM. Nurses' experience in clinical encounters with children experiencing abuse and their parents. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:2718–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Feng JY, Huang TY, Wang CJ. Kindergarten teachers' experience with reporting child abuse in Taiwan. Child Abuse Negl 2010;34:124–8. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013942supp001.pdf (596.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013942supp002.pdf (320.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013942supp003.pdf (188.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013942supp004.pdf (503.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013942supp005.pdf (488.4KB, pdf)