Abstract

Laryngeal involvement is a rare manifestation of mycosis fungoides (MF), with only nine reported cases of cutaneous T cell lymphoma with laryngeal or vocal cord involvement. Herein, we report the case of a patient with a 7-year history of MF who presented to the emergency department with hoarseness, throat tightness and cough, as well as erythroderma and skin tumours. Laryngoscopy and CT imaging were concerning for lymphomatous involvement of the left false vocal cord. A biopsy was taken of the false vocal cord lesion, which revealed an aberrant immunophenotype consistent with MF. The patient was started on doxorubicin with initial rapid improvement in symptoms. Within 2 months, her respiratory status and skin involvement worsened. Subsequent studies showed bone marrow involvement. The patient expired 4 months after original presentation. This report describes the patient’s presentation and clinical course, and reviews the literature on vocal cord and laryngeal involvement of MF.

Keywords: dermatology; ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology; immunology

Background

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL), and usually presents with erythematous patches, plaques and tumours. Advanced disease involves a leukaemic phase (Sézary syndrome), often with involvement of viscera and other extracutaneous sites. Progression to leukaemic phase and extracutaneous involvement often confers poor prognosis and requires treatment with single or multiagent chemotherapy.1 2

Laryngeal involvement is an exceeding rare complication of MF; to date, there are only nine reported cases in the literature of CTCL with laryngeal or vocal cord involvement.3–10 MF has been shown to involve the arytenoids, aryepiglottic fold, epiglottis, and true and false vocal cords.6 8 We report on a patient with a 7-year history of MF who presented to the emergency department with hoarseness and concerning respiratory symptoms. Laryngoscopy and biopsy revealed MF involvement of the left false vocal cord.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old woman with a 7-year history of MF presented to the emergency department with progressive ‘throat tightness’ along with hoarseness of her voice and cough. The patient’s MF was treated with psoralen and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) and acitretin for the first 6 years of her disease. The patient was transitioned to treatment with narrowband ultraviolet B radiation (narrowband UVB) during the seventh year of disease secondary to intolerance of methoxsalen. Vorinostat was also started during the seventh year of disease after flow cytometry revealed leukaemic blood involvement. Minimal clinical benefit was observed with vorinostat and previous trials of acitretin, so these medications were discontinued 2 months prior to presentation. Current topical medications included triamcinolone 0.1% external ointment and fluocinonide 0.05% external ointment.

Since discontinuation of vorinostat, the patient noted worsening of a chronic cough as well as hoarseness of her voice for 2 weeks. She denied shortness of breath, fevers, chills, night sweats, nausea, vomiting or difficulty swallowing. She endorsed significant pruritus, managed with hydroxyzine and doxepin. She had no other significant medical history, including other cancers, diabetes, or cardiovascular, liver or kidney disease. Social history was negative for smoking or alcohol use. Family history was significant for cancer on the paternal side of the family (melanoma, breast, lung, prostate, pancreatic, bladder) and cardiovascular disease on the maternal side.

Investigations

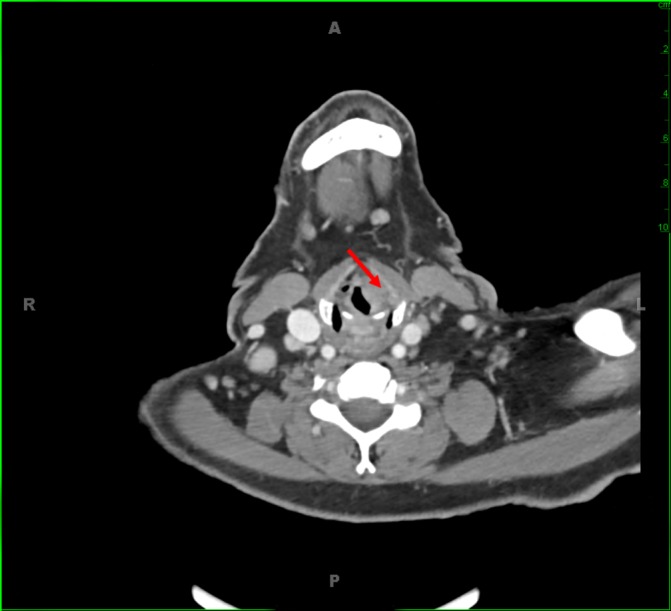

On presentation to the emergency department, ear, nose and throat (ENT) and dermatology consults were placed. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy revealed a left false vocal cord lesion, which was also seen on CT with contrast (figure 1). This lesion was biopsied by ENT the following day. On skin exam, the patient was found to be erythrodermic with several cutaneous tumours, which were biopsied by dermatology (figure 2). Flow cytometry of the peripheral blood was sent.

Figure 1.

Appearance of the laryngeal lesion on CT imaging. Left supraglottic lesion with effacement of the left paraglottic fat is shown by the red arrow.

Figure 2.

Patient skin findings at time of presentation. Diffuse erythroderma and tumours were found on the patient’s back (upper left), chest (upper right) and extremities (lower left and right) at time of presentation, indicating advanced mycosis fungoides.

Laryngoscopy with biopsy

Biopsy of the left false vocal cord lesion under general anaesthesia was performed using an adult Kleinsasser and cupped forceps. Grossly, there was a smooth, broad-based, 1 cm lesion centred over the left false vocal cord with extension anteriorly and inferiorly towards the anterior commissure of the true vocal cords. The true vocal cords were not grossly involved. Careful inspection of the oral cavity, bilateral tonsils, posterior oropharynx, base of tongue and lingual surface of the epiglottis was unremarkable. Multiple biopsies were acquired from the left false vocal cord lesion.

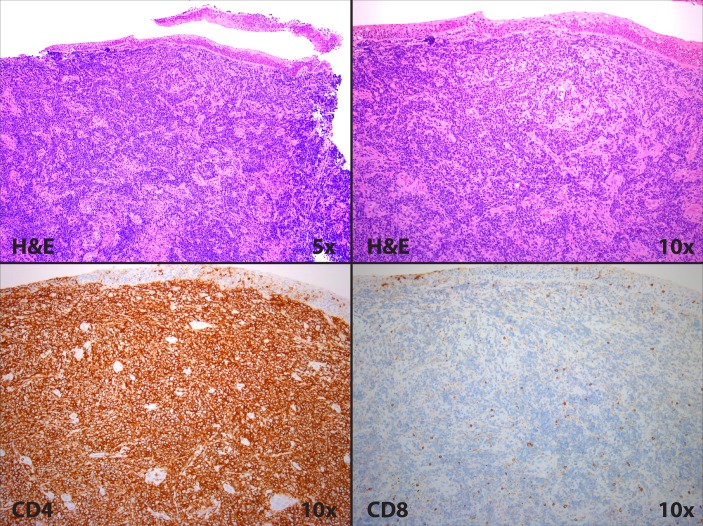

Pathology of false vocal cord lesion

Pathological evaluation revealed infiltrating cords and sheets of large atypical lymphoid cells in a heavily sclerosed stroma (figure 3). Immunohistochemistry revealed lymphocytes negative for CD20 and cytokeratin and positive for CD5 and CD4. Expression of CD3 was weak, and CD7 was aberrantly absent. Overall, the population was uniformly CD4-positive and CD8-negative.

Figure 3.

Pathological evaluation of left false vocal cord lesion showing a predominance of CD4-positive lymphocytes.

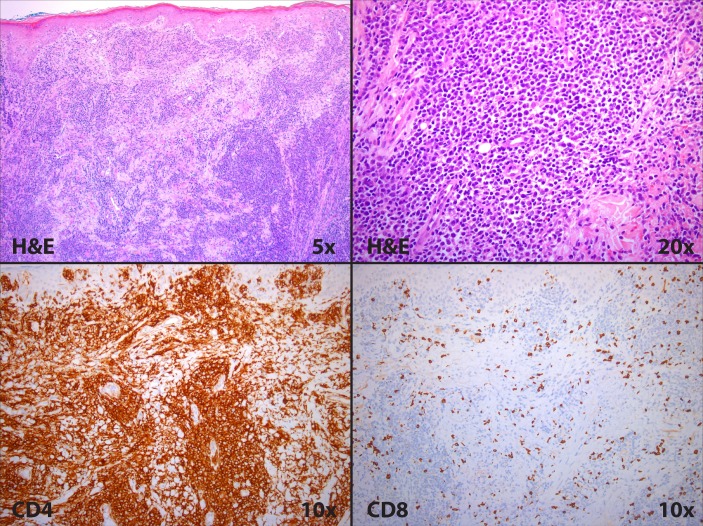

Pathology of punch biopsy of distal right arm lesion

A punch biopsy from the distal right arm showed pandermal infiltrates by mononuclear cells exhibiting large cell morphologies. Admixed with large cells were smaller, reactive appearing lymphocytes with minimal epidermal involvement. Immunohistochemistry revealed lymphocytes that were positive for CD5 and CD4, and negative for CD3, CD7 and CD8. The CD4:CD8 ratio was markedly elevated, and CD30 stain highlighted rare enlarged cells (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pathological evaluation of skin lesion showing clusters of atypical lymphocytes and a predominance of CD4-positive cells.

Evaluation of peripheral blood

Review of the Wright-Giemsa stain peripheral smear showed normochromic, normocytic red blood cells with rare atypical lymphocytes. The platelets appeared normal in number and morphology. No definitive Sézary cells were identified. A 100-cell differential showed 30% neutrophils, 28% band cells, 17% lymphocytes, 8% monocytes, 14% eosinophils and 2% basophils. On flow cytometry, there was a small T cell population with increased CD4:CD8 ratio. The small T cell population with increased CD4:CD8 ratio and loss of CD7 and CD26 was consistent with a low-level involvement of a previously diagnosed T cell lymphoma.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a vocal cord lesion in this patient included the following:

CTCL

squamous cell carcinoma

vocal cord nodule or polyp

tuberculosis

fungal infection

other granulomatous processes.

After pathological evaluation, the differential diagnosis for lymphocytic laryngeal infiltrates included the following:

lymphomas, including CTCL

multiple myeloma

acute or chronic leukaemia.

Treatment

Given the concern for large cell transformation (LCT) on pathology, doxorubicin at 40 mg/m2 (once/month) was chosen as treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

One week after vocal cord and skin biopsies, the patient stated that she was speaking better, although she was still very hoarse. She noted her cough was reduced in frequency and that she was having less gagging associated with coughing.

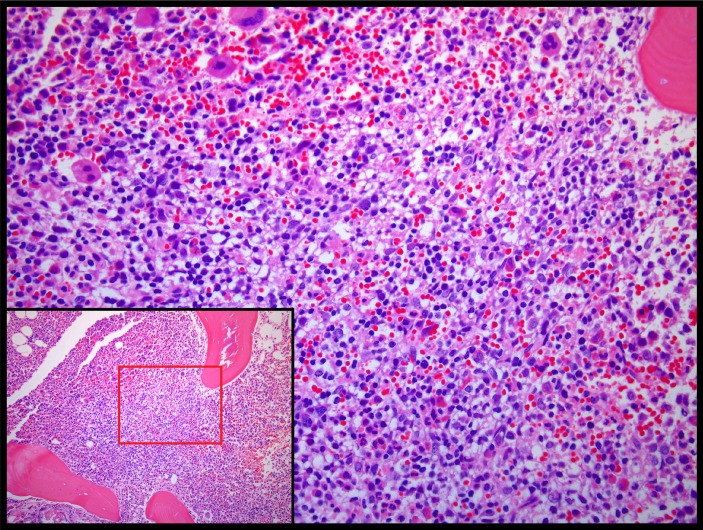

After 5 weeks on doxorubicin (two doses), she developed increased cough and hoarseness, similar to the stridor symptoms she had experienced at initial presentation. In addition, she noted worsening erythroderma and tumour formation. Iliac crest biopsy at this time showed hypercellular bone marrow with lymphoid aggregates consistent with involvement by T cell lymphoma (figure 5). Her disease continued to progress until she expired approximately 3 months later.

Figure 5.

Pathological evaluation of left iliac crest bone marrow biopsy showing hypercellular bone marrow with lymphoid aggregates consistent with involvement by T cell lymphoma.

Discussion

MF is a rare, intraepithelial proliferation of malignant T cells. Early cutaneous manifestations of MF include erythematous patches and plaques, and intense pruritus is a frequent and often debilitating symptom.11 Progression to cutaneous tumours or generalised erythroderma confers poor prognosis and often indicates blood involvement or extracutaneous disease.12 13 The most frequently involved organs in extracutaneous disease include the lungs, spleen, liver, kidneys, thyroid, pancreas, bone marrow and heart.8 Laryngeal involvement with MF has been reported in autopsy studies14 15; however, symptomatic laryngeal MF is much less common.

The most common presentation of laryngeal MF includes dysphagia and/or hoarseness. Redleaf et al9 published a report on a patient with a chief complaint of both dysphagia and hoarseness, and endoscopy with subsequent biopsy was consistent with MF. Kuhn et al6 published a series of two patients with laryngeal MF and a presentation of hoarseness, with one patient also endorsing dysphagia. Maleki and Azmi8 reported on a patient with MF of the true vocal cord and subglottic region who presented with both dysphagia and hoarseness. Ferlito and Recher describe a patient with highly disseminated MF and dysphagia after total skin electron beam therapy. Biopsy of the lesion revealed a dense infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes consistent with MF. Lippert et al7 report on a patient with a 1-year history of MF who presented with dysphagia and dysphonia. Further work-up was significant for a supraglottic lesion with extension towards the false vocal cords and a secondary lesion infiltrating the maxillary sinus. Biopsies of both lesions were consistent with MF.

Further, a complaint of hoarseness or dysphagia may be a harbinger of MF. Hood et al5 describe a patient with dysphagia and a tumour of the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic fold. Biopsy of the tumour was read as undifferentiated malignant neoplasm, and symptoms cleared with radiation therapy. Skin lesions appeared 2 years later, and subsequent skin and laryngeal biopsies were consistent with MF. Tutarel et al published a brief report on a patient who presented with dysphagia 2 years after liver transplant, and biopsy of a laryngeal tumour first established the diagnosis of MF.10 Similarly, Gordon et al published a case of MF with lesions on the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis, and subsequent work-up established a new diagnosis of MF.4 This patient had a 6-month history of dysphagia before indirect laryngoscopy was performed. In the case presented herein, unexplained hoarseness on presentation was an indication for laryngoscopy. We conclude that the differential diagnosis for patients with MF who present with hoarseness or dysphagia should include laryngeal involvement with MF.

Histological diagnosis of MF in early disease is difficult, as typical findings include a non-specific lymphocytic band-like or patchy lichenoid infiltrate.16 Atypical lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and clear cytoplasm and Pautrier microabscesses, which are small aggregates of atypical lymphocytes associated with Langerhans cells, are more specific for MF but are seen in only a fraction of cases.16 Ancillary studies such as immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry are often used to help establish the diagnosis of MF. Typical findings include CD4+/CD8− lymphocytes with variable loss of CD7 or CD15.17 Consistent with these findings, biopsies from the skin and false vocal cord in this study showed a predominance of CD4+/CD8− lymphocytes with aberrant or negative CD7 expression. Flow cytometry of peripheral blood showed an increased CD4/CD8 ratio with loss of CD7. Given the clinical presentation and pathology findings, we are confident in the diagnosis of disseminated MF with true involvement of the larynx.

Extracutaneous involvement of MF carries almost universally a poor prognosis, with median survival of 13 months.12 Treatment recommendations for extracutaneous MF remain highly debated. Single therapy options include doxorubicin, gemcitabine, pralatrexate, romidepsin, purine or pyrimidine analogues, and monoclonal antibodies such as pembrolizumab. The patient herein was treated with standard of care throughout her disease process, including PUVA, narrowband UVB, acitretin, and topical corticosteroids. Vorinostat was initiated once systemic disease was identified. When considering her presentation and concerns for LCT on pathology, we chose doxorubicin for further medical management. In general, LCT of MF portends a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival of less than 20%.18 CD30 expression may help differentiate MF with LCT from cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma,19 and CD30-negative MF with LCT is associated with reduced disease-specific survival.20 There are no clear guidelines on the treatment of MF with LCT; however, advanced stage MF with LCT often requires aggressive systemic therapy. Unfortunately, our patient’s disease continued to progress until she expired. Treatment of extracutaneous MF remains difficult and requires further research to establish new and more efficacious therapeutic options.

Learning points.

Mycosis fungoides of the vocal cords is a rare extracutaneous manifestation of cutaneous T cell lymphoma.

Vocal cord involvement with mycosis fungoides often presents with dysphagia or hoarseness.

Extracutaneous mycosis fungoides remains difficult to treat and confers a poor prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank our astute dermatopathologist, Andy Hsi, MD, for his assistance with the dermatopathology.

Footnotes

Contributors: TMB wrote the manuscript, constructed the figures, and helped with project design. CMW helped with project design and literature review. ACM provided care for the patient, helped with project design, and provided edits to the manuscript. KMN managed the project, collected data, and provided edits to the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Scarisbrick JJ, Kim YH, Whittaker SJ, et al. Prognostic factors, prognostic indices and staging in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: where are we now? Br J Dermatol 2014;170:1226–36. 10.1111/bjd.12909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2014 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2014;89:837–51. 10.1002/ajh.23756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlito A, Recher G. Laryngeal involvement by mycosis fungoides. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1986;95:275–7. 10.1177/000348948609500312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon LJ, Lee M, Conley JJ, et al. Mycosis fungoides of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:120–3. 10.1177/019459989210700120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hood AF, Mark GJ, Hunt JV, et al. Laryngeal mycosis fungoides. Cancer 1979;43:1527–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn JJ, Wenig BM, Clark DA. Mycosis fungoides of the larynx. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;118:853–8. 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880080075016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippert BM, Höft S, Teymoortash A, et al. Mycosis fungoides of the larynx: case report and review of the literature. Otolaryngol Pol 2002;56:661–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maleki Z, Azmi F. Mycosis fungoides of the true vocal cord: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Iran Med 2010;13:429–31. doi:010135/AIM.0012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redleaf MI, Moran WJ, Gruber B. Mycosis fungoides involving the cervical esophagus. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993;119:690–3. 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880180110022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tutarel O, Barg-Hock H, Pischke S, et al. Mycosis fungoides with involvement of the larynx after liver transplantation in an adult. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:238–40. 10.1038/ajg.2009.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahern K, Gilmore ES, Poligone B. Pruritus in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:760–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Coninck EC, Kim YH, Varghese A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with extracutaneous mycosis fungoides. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:779–84. 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood 2007;110:1713–22. 10.1182/blood-2007-03-055749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein EH, Levin DL, Croft JD, et al. Mycosis fungoides. Survival, prognostic features, response to therapy, and autopsy findings. Medicine 1972;51:61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rappaport H, Thomas LB. Mycosis fungoides: the pathology of extracutaneous involvement. Cancer 1974;34:1198–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massone C, Kodama K, Kerl H, et al. Histopathologic features of early (patch) lesions of mycosis fungoides: a morphologic study on 745 biopsy specimens from 427 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:550–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralfkiaer E. Immunohistological markers for the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphomas. Semin Diagn Pathol 1991;8:62–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salhany KE, Cousar JB, Greer JP, et al. Transformation of cutaneous T cell lymphoma to large cell lymphoma. A clinicopathologic and immunologic study. Am J Pathol 1988;132:265–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadin ME, Hughey LC, Wood GS. Large-cell transformation of mycosis fungoides-differential diagnosis with implications for clinical management: a consensus statement of the US cutaneous lymphoma consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:374–6. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benner MF, Jansen PM, Vermeer MH, et al. Prognostic factors in transformed mycosis fungoides: a retrospective analysis of 100 cases. Blood 2012;119:1643–9. 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]