Abstract

Objectives

To determine the accuracy of the recruitment status listed on ClinicalTrials.gov as compared with the actual trial status.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis.

Setting

Random sample of interventional phase 2–4 clinical trials registered between 2010 and 2012 on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Primary outcome measure

For each trial which was listed within ClinicalTrials.gov as ongoing, two investigators performed a comprehensive literature search for evidence that the trial had actually been completed. For each trial listed as completed or terminated early by ClinicalTrials.gov, we compared the date that the trial was actually concluded with the date the registry was updated to reflect the study’s conclusion status.

Results

Among the 405 included trials, 92 had a registry status indicating that study activity was either ongoing or the recruitment status was unknown. Of these, published results were available for 34 (37%). Among the 313 concluded trials, the median delay between study completion and a registry update reflecting that the study had ended was 141 days (IQR 48–419), with delays of over 1 year present for 29%. In total, 125 trials (31%) either had a listed recruitment status which was incorrect or had a delay of more than 1 year between the time the study was concluded and the time the registry recruitment status was updated.

Conclusions

At present, registry recruitment status information in ClinicalTrials.gov is often outdated or wrong. This inaccuracy has implications for the ability of researchers to identify completed trials and accurately characterise all available medical knowledge on a given subject.

Keywords: epidemiology, World Wide Web technology, trial registration, ClinicalTrials.gov

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Registry recruitment status is often used to identify completed clinical trials, yet the reliability of this information has not been previously assessed.

The study involved comprehensive, independent literature searches by multiple investigators, including a medical research librarian.

This study design is unable to identify studies which were completed but not published.

Introduction

Clinical trial registries play an essential role in helping to ensure the integrity of the published medical literature.1 When used appropriately by investigators and sponsors, registration helps to ensure that a publicly accessible trial record exists even when results are not published in a peer-reviewed journal, and that published outcome measures are consistent with prospectively specified trial outcomes. For these reasons, trial registries are a particularly important tool for systematic reviewers as they attempt to identify both published and unpublished trial data in order to assess for the possibility of publication bias.2

Despite the critical importance of trial registration, compliance with requirements from both the ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors) and governmental regulators which mandate the prospective registration of clinical trials has been imperfect.3 4 Meta-researchers have begun using data from ClinicalTrials.gov and other registries to identify these patterns of limited compliance in order to publicise and monitor deficiencies.1 5 6

Within ClinicalTrials.gov, users have the option of using the ‘advanced search’ function to restrict search results to only those trials with a particular recruitment status (ie, not yet recruiting, recruiting, completed, and so on). Systematic reviewers and meta-researchers often limit registry searches to trials for which subject recruitment is documented in the registry as having been completed.5 7–13 Restricting reviews to completed studies makes sense because these are the studies for which all the data are completed and for which the results either are known or could be known. However, little is known about delays between the time of study completion and the time that ClinicalTrials.gov is updated to reflect this completion, or the percentage of completed trials which remain listed with an ongoing status in ClinicalTrials.gov indefinitely. If these delays are significant or a large proportion of registry entries are never updated to reflect study completion, then limiting registry searches to only entries with a completed registry status might miss otherwise relevant trials.

The objective of this study is to quantify delays observed between the end of subject recruitment in registered clinical trials, and the time that the registry entries are updated to reflect that recruitment has ended.

Methods

Study selection and data collection

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov for phase 2–4 interventional studies registered between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012. From these potentially eligible trials (n=30 524) we randomly selected 500 studies for analysis. Studies with a recruiting status of withdrawn were excluded, as this indicates that the study was halted prior to enrolling any participants. Trials with a recruiting status indicating that recruitment was ongoing and a planned primary completion date (date that primary outcome data for the final subject are collected) listed within ClinicalTrials.gov as being after 1 January 2016 were also excluded, as we hypothesised that the yield from a publication search for trials completed after this date would be low. For each included trial, we obtained information on study phase, size, sponsor, participant demographics and recruitment status as of 1 January 2017 directly from ClinicalTrials.gov.

Dates for the following events were also recorded from ClinicalTrials.gov for each included trial: initial registration, study start and primary completion date (date on which primary outcome data for the last trial participant were collected). When the primary completion date field was missing, we used the study completion date (final date on which any trial data were collected). We considered trials with recruitment statuses of either completed (study concluded normally) or terminated (recruitment stopped prematurely and will not resume) to indicate that the study had ended and was unlikely to resume activity. These trials were classified as concluded. We recorded the dates on which the registry entries were updated to reflect that trials had concluded from the History of Changes section within each registry entry. Recruiting statuses which did not clearly reflect that the trial had concluded were recruiting, enrolling by invitation, not yet recruiting, active not recruiting, suspended and unknown. Trials which were registered more than 1 month after the study start date were considered retrospectively registered.

Ongoing or unknown completion status trials

For studies which did not have an updated recruitment status indicating that they had concluded, we performed a comprehensive literature search to identify published evidence that the trial might in fact have been completed. An investigator first reviewed the relevant ClinicalTrials.gov entry for relevant publications and searched Medline via PubMed using trial registration number, keywords, condition studied, intervention, trial title and investigators’ names for matching manuscripts. When the first search identified no corresponding publication, a research librarian repeated this search using PubMed, Embase and Google Scholar. The final publication search occurred between January and February 2017.

We assessed matches between registry entries and publications identified by this search strategy using the following trial characteristics: study title, trial design, interventions, primary and secondary outcomes, number of participants, recruitment dates, location and funding sources. We did not consider trials to be published if the publication did not include outcome data from the primary trial. For example, trial protocols for ongoing trials were not considered evidence of trial completion. We did consider published abstracts and presentations at scientific meetings to be evidence of trial completion, and counted these as publications for this analysis. For the group of included trials with an ongoing or unknown recruitment status listed in the registry, the primary outcome was the proportion of studies with outcomes published in the medical literature.

Concluded trials

For studies which were indicated to be concluded based on the recruitment status listed in ClinicalTrials.gov, the primary outcome was the amount of time elapsed between the primary completion date listed in ClinicalTrials.gov and the date on which the ClinicalTrials.gov registry entry was actually updated to indicate that the study had ended and was unlikely to resume activity.

Secondary outcomes included the proportion of studies registered more than 1 month after study initiation, and the proportion of studies registered after study completion. We also compared results among subgroups based on trial phase, trial size and funding source.

We calculated descriptive data for the primary and secondary outcomes. We also compared the median time elapsed between the change in recruiting status and the time ClinicalTrials.gov was updated to reflect this change between subgroups using Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test. χ2 tests were used to make comparisons between categorical variables. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using PASW V.18.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The data set generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

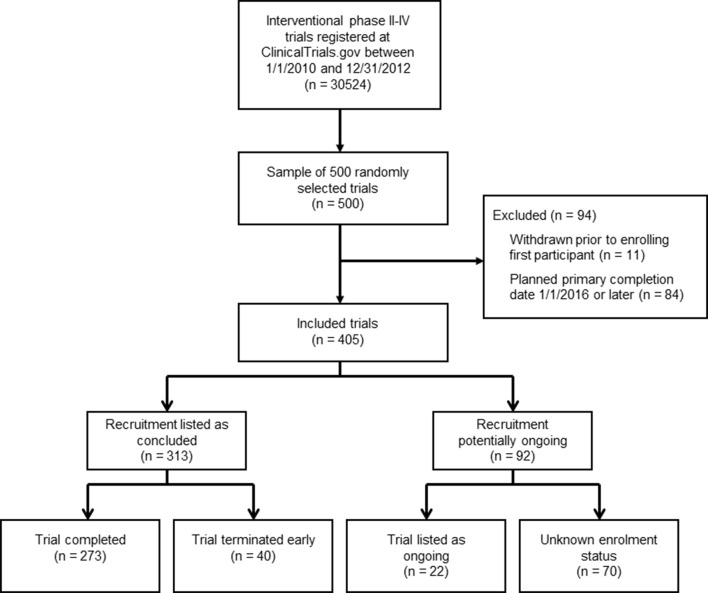

Of the 500 potentially eligible trials which were randomly selected for evaluation, 405 were eligible for inclusion (figure 1). Phase 2, 3 and 4 trials were all well represented within the study sample, and the majority of trials (53%) had received at least partial industry funding (table 1). A large proportion of trials were registered retrospectively, more than 1 month after the study had started (39%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included trials.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials

| Trial characteristics | All trials (n=405) |

Concluded (n=313) |

Potentially ongoing (n=92) |

| Number of participants, median (IQR) | 80 (32–225) | 80 (30–230) | 80 (40–173) |

| Trial phase, n (%) | |||

| Phase 2 | 186 | 147 (79) | 39 (21) |

| Phase 3 or 2/3 | 132 | 101 (77) | 31 (23) |

| Phase 4 | 87 | 65 (75) | 22 (25) |

| Funding source, n (%)* | |||

| Industry | 214 | 187 (87) | 27 (13) |

| NIH/US government | 23 | 17 (74) | 6 (26) |

| Other | 233 | 155 (67) | 78 (33) |

| Trial start date, n (%) | |||

| Unlisted | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| Prior to 2006 | 15 | 14 (93) | 1 (7) |

| 2006–2009 | 37 | 29 (78) | 8 (22) |

| 2010–2011 | 235 | 176 (75) | 59 (25) |

| 2012–2014 | 116 | 93 (80) | 23 (20) |

| Registered retrospectively, n (%)† | 159 | 124 (78) | 35 (22) |

| Registered prospectively, n (%) | 245 | 189 (77) | 56 (23) |

| Major discrepancy in recruitment status‡ | 125 | 91 (73) | 34 (27) |

*Trials could have more than one funding source.

†Registration timing relative to recruitment could not be determined for one study.

‡Listed recruitment status within ClinicalTrials.gov was incorrect or there was a delay of more than 1 year between when the study concluded and when the registry recruitment status was updated to reflect that recruitment ended.

NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Out of the 405 included trials, 273 (67%) were listed in ClinicalTrials.gov with a study status of completed, and 40 (10%) had initiated subject recruitment but were terminated early. Ninety-two trials (23%) had a recruitment status which indicated that trial activities were ongoing or that the study status was unknown, including 22 (5%) listed as active or active but not recruiting, and 70 (17%) listed as having an unknown recruiting status. Of these 92 trials with statuses in ClinicalTrials.gov indicating potentially ongoing study activity, we identified a corresponding publication containing outcome data for 34 trials (37%).

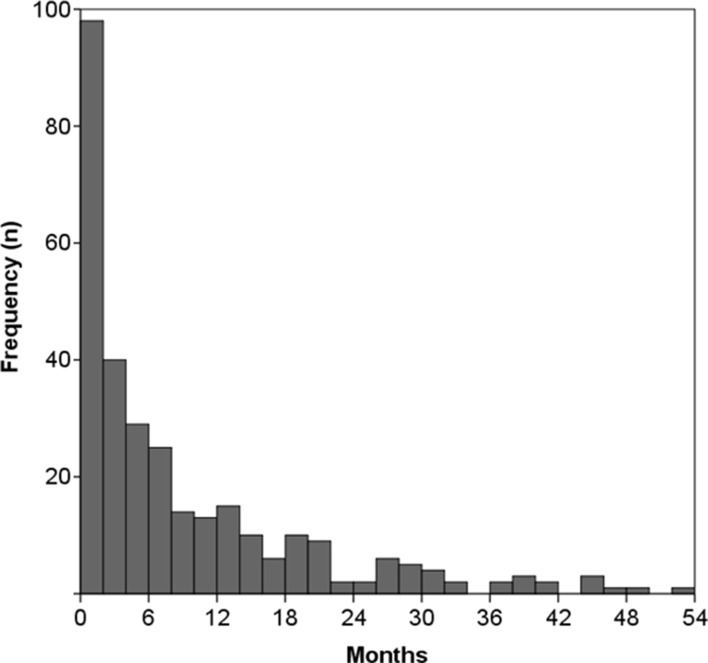

Among the trials with a completed or terminated status (n=313), two were missing the study completion date. Of the remaining 311 trials, the median delay between when a trial was completed and when ClinicalTrials.gov was updated to reflect this change was 142 days (IQR 48–419), with a mean delay of 340 days. For 127 trials (41%), the recruitment status was changed promptly, with a delay of less than or equal to 90 days. In 91 trials (29%) this delay was greater than 1 year, and in 39 trials (13%) the delay was greater than 2 years (figure 2). Eight trials had delays of more than 5 years. Retrospectively registered trials had a median delay of 266 days (IQR 62–650 days) between trial completion and when the registered recruitment status was updated, compared with a median of 116 days (IQR 38–260) for prospectively registered trials (p<0.001). Observed delays did not differ between trials according to funding source or trial phase.

Figure 2.

Delays in updating ClinicalTrials.gov following trial conclusion. Histogram of completed or terminated trials (n=311), depicting delays between the actual date of trial conclusion and the date on which ClinicalTrials.gov was updated to indicate trial conclusion. Does not show eight outliers with delays of greater than 54 months. Trial completion dates were also not listed for two trials.

When considering all 405 included trials, 125 (31%) either had a listed recruitment status which was incorrect (ie, trial had been completed but was not listed as such) or had a delay of more than 1 year between the time the study was completed and the time the recruitment status was updated. Retrospectively registered trials were more likely than prospectively registered trials to have one of these major discrepancies in recruitment status, with discrepancies observed for 46% of retrospectively registered trials and 21% of prospectively registered trials (p<0.001). Major recruitment status discrepancies were particularly common among those trials registered more than 1 year after the onset of recruitment (37/56, 66%). Major recruitment status discrepancies were also very common among trials which started recruitment before 2006 (14/15, 93%), though this estimate is based on a very small number of trials. Major discrepancies were less common, but not unusual among trials which started recruitment from 2006 to 2009 (21/37, 57%), from 2010 to 2011 (59/235, 25%) and from 2012 to 2014 (31/116, 27%). Recruitment status discrepancies did not differ among trials based on funding source or trial phase.

Discussion

Among this sample of over 400 phase 2–4 trials registered with ClinicalTrials.gov between 2010 and 2012, we identified frequent discrepancies between trial recruitment statuses listed on ClinicalTrials.gov and the actual trial status. Specifically, 37% of trials which were indicated to be ongoing based on available information within the registry had been completed and published. Among completed trials, 29% had a delay of more than a year between trial completion and the ClinicalTrials.gov update reporting trial completion.

Trial registries are an important tool by which both the authors of clinical guidelines and systematic reviewers can identify relevant clinical trials.2 14 However, in both cases authors often assume that the listed recruitment status is accurate and either restrict their registry searches to completed trials,7–9 or conclude that those trials with active recruitment statuses are actually still ongoing.15–19 Our findings show that this assumption is incorrect for a substantial portion of trials. Recruitment status discrepancies were particularly common among trials registered before 2006 and among retrospectively registered trials, which may reflect poor investigator familiarity with registry use in general, failure to prioritise correct registry use or changing registration patterns over time.

One potential solution to the problem of outdated recruitment status information is to not limit registry searches to completed trials. For trials which are listed as ongoing, efforts should be made to confirm the recruitment status or search for published results regardless of the registered recruitment status. In addition to a comprehensive search for published results, in some cases these efforts should include contacting investigators or study sponsors to confirm recruitment status. Given the high rate of recruitment status discrepancies observed among retrospectively registered trials and trials registered prior to 2006, the listed ClinicalTrials.gov recruitment status should be considered particularly unreliable for these trials.

Trial registries serve as a critical source of data about ongoing and completed trials which supplements the published medical literature. However, our findings are consistent with previous studies which have demonstrated that registry information is at times incomplete or out of date.5 20 This work is performed by meta-researchers who use registry information to measure compliance with trial registration requirements and to monitor the conduct and reporting of clinical trials.1 In order to accurately perform this function, it is also important for meta-researches to recognise the limitations we describe with respect to registered trial recruiting statuses. This is particularly important for registry-based investigations into publication bias, as excluding registered trials with a registry status indicating that recruitment is ongoing may miss trials which have actually finished enrolment without updating the associated registry entry.5 10–13

Several important limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, our findings are based on a sample of phase 2–4 trials registered from 2010 to 2012; these general results may not be applicable to specific classes of clinical trials, and the patterns we observed may change over time. Additionally, we performed a literature search to identify trials which were listed in the registry as being ongoing, but which had actually been completed. It is likely that some additional trials were completed but not yet published; our search would not have identified these trials. Similarly, our literature search may have missed some trials. For these reasons, we may have underestimated the percentage of trials which were completed without updating the registry’s recruitment status.

Conclusions

In summary, we observed that a significant percentage of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov with a recruitment status indicating that the trial is ongoing have actually been completed. Additionally, among completed trials, we observed significant delays in updating the ClinicalTrials.gov recruitment status. Individuals using registry data to supplement a systematic literature search and meta-researchers using registry data to study the conduct and reporting of clinical trials should be aware of these findings to avoid unwarranted assumptions about the recruitment status of registered trials.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CJ conceived the study. CJ, MS, AA and TFPM all contributed to the study design. CJ, MS and AA performed data collection. CJ performed data analysis and interpretation and drafted the article. All authors provided critical revisions to the article, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: CJ is an investigator on unrelated studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Roche Diagnostics, Inc, and Janssen, for which his department received research grants. The remaining authors declare no additional competing interests.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The full data set is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, et al. Update on trial registration 11 years after the ICMJE policy was established. N Engl J Med 2017;376:383–91. 10.1056/NEJMsr1601330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones CW, Keil LG, Weaver MA, et al. Clinical trials registries are under-utilized in the conduct of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional analysis. Syst Rev 2014;3:126 10.1186/2046-4053-3-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Hines EM, et al. Trial publication after registration in ClinicalTrials.Gov: a cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000144 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mathieu S, Boutron I, Moher D, et al. Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2009;302:977–84. 10.1001/jama.2009.1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anderson ML, Chiswell K, Peterson ED, et al. Compliance with results reporting at ClinicalTrials.gov. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1031–9. 10.1056/NEJMsa1409364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones CW, Keil LG, Holland WC, et al. Comparison of registered and published outcomes in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. BMC Med 2015;13:282 10.1186/s12916-015-0520-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jun M, Foote C, Lv J, et al. Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1875–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60656-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karagiannis T, Paschos P, Paletas K, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the clinical setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;344:e1369 10.1136/bmj.e1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li L, Shen J, Bala MM, et al. Incretin treatment and risk of pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ 2014;348:g2366 10.1136/bmj.g2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dechartres A, Riveros C, Harroch M, et al. Characteristics and public availability of results of clinical trials on rare diseases registered at Clinicaltrials.gov. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:556–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones CW, Handler L, Crowell KE, et al. Non-publication of large randomized clinical trials: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2013;347:f6104 10.1136/bmj.f6104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Powell-Smith A, Goldacre B. The trialstracker: automated ongoing monitoring of failure to share clinical trial results by all major companies and research institutions. F1000Res 2016;5:2629 10.12688/f1000research.10010.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ross JS, Tse T, Zarin DA, et al. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2012;344:d7292 10.1136/bmj.d7292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Heart Association. Methodology manual and policies from the ACCF/AHA task force on practice guidelines, 2010. https://professional.heart.org/idc/groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/documents/downloadable/ucm_319826.pdf (accessed 2 Sep 2017).

- 15. Robinson PD, Kalkanis SN, Linskey ME, et al. Methodology used to develop the AANS/CNS management of brain metastases evidence-based clinical practice parameter guidelines. J Neurooncol 2010;96:11–16. 10.1007/s11060-009-0059-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zarychanski R, Abou-Setta AM, Turgeon AF, et al. Association of hydroxyethyl starch administration with mortality and acute kidney injury in critically ill patients requiring volume resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;309:678–88. 10.1001/jama.2013.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P, et al. Effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;344:e3054 10.1136/bmj.e3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bergman P, Lindh AU, Björkhem-Bergman L, et al. Vitamin D and respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2013;8:e65835 10.1371/journal.pone.0065835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Masters GA, Temin S, Azzoli CG, et al. Systemic therapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3488–515. 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Riveros C, Dechartres A, Perrodeau E, et al. Timing and completeness of trial results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in journals. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001566 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.