Abstract

Objectives

This umbrella review aimed to identify the current evidence on health education-related interventions for patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM); identify the educational content, delivery methods, intensity, duration and setting required. The purpose was to provide recommendations for educational interventions for high-risk patients with both ACS and T2DM.

Design

Umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Setting

Inpatient and postdischarge settings.

Participants

Patients with ACS and T2DM.

Data sources

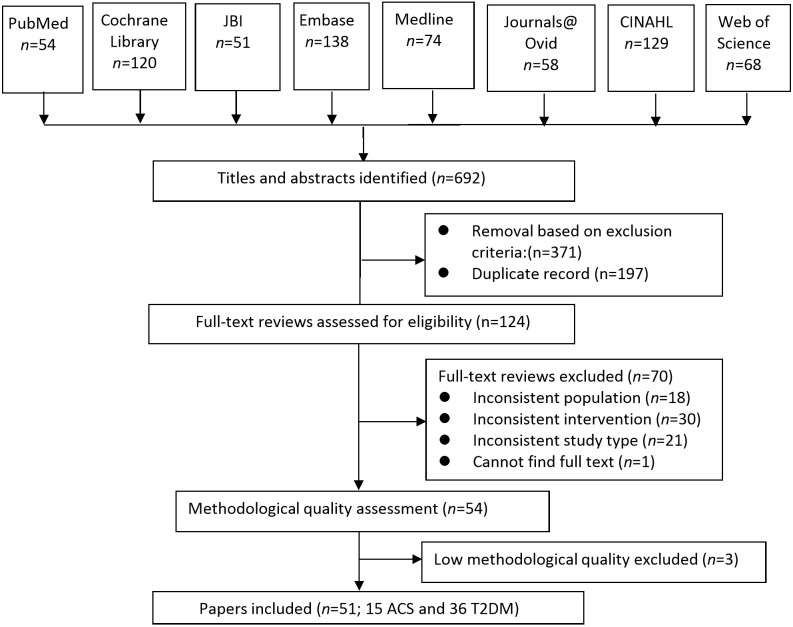

CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs Institute, Journals@Ovid, EMBase, Medline, PubMed and Web of Science databases from January 2000 through May 2016.

Outcomes measures

Clinical outcomes (such as glycated haemoglobin), behavioural outcomes (such as smoking), psychosocial outcomes (such as anxiety) and medical service use.

Results

Fifty-one eligible reviews (15 for ACS and 36 for T2DM) consisting of 1324 relevant studies involving 2 88 057 patients (15 papers did not provide the total sample); 30 (58.8%) reviews were rated as high quality. Nurses only and multidisciplinary teams were the most frequent professionals to provide education, and most educational interventions were delivered postdischarge. Face-to-face sessions were the most common delivery formats, and many education sessions were also delivered by telephone or via web contact. The frequency of educational sessions was weekly or monthly, and an average of 3.7 topics was covered per education session. Psychoeducational interventions were generally effective at reducing smoking and admissions for patients with ACS. Culturally appropriate health education, self-management educational interventions, group medical visits and psychoeducational interventions were generally effective for patients with T2DM.

Conclusions

Results indicate that there is a body of current evidence about the efficacy of health education, its content and delivery methods for patients with ACS or T2DM. These results provide recommendations about the content for, and approach to, health education intervention for these high-risk patients.

Keywords: health education, acute coronary syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, umbrella review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This umbrella review is the first synthesis of systematic reviews or meta-analyses to consider health education-related interventions for patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

These results provide recommendations about the content of a health education intervention for patients with ACS and T2DM.

The diversity of the educational interventions seen in the reviews included in this umbrella review may reflect the uncertainty about the optimal strategy for providing health education to patients.

This umbrella review found no reviews focused on patients with ACS and T2DM—the intended target group; instead, all of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses focused on only one of these two diseases.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is the leading cause of death worldwide. The risk of high mortality rates relating to ACS is markedly increased after an initial cardiac ischaemic event.1 Globally, 7.2 million (13%) deaths are caused by coronary artery disease (CAD),2 and it is estimated that >7 80 000 persons will experience ACS each year in the USA.3 Moreover, about 20%–25% of patients with ACS reportedly also have diabetes mellitus (DM); predominantly type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM)).4 5 Patients with ACS and DM have an increased risk of adverse outcomes such as death, recurrent myocardial infarction (MI), readmission or heart failure during follow-up.6 Longer median delay times from symptom onset to hospital presentation, have been reported among patients with ACS and DM than patients with ACS alone.7

DM is now considered to confer a risk equivalent to that of CAD for patients for future MI and cardiovascular mortality.8 Mortality was significantly higher among patients with ACS and DM than among patients with ACS only following either ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (8.5% (ACS and DM) vs 5.4% (ACS)) or unstable angina/non-STEMI (NSTEMI) (2.1% (ACS and DM) vs 1.1% (ACS)).9 ACS and T2DM are often associated with high-risk factors such as low levels of physical exercise, obesity, smoking and unhealthy diet.10 Some of these and other risk factors, specifically glycaemia, high blood pressure (BP), lipidaemia and obesity, are frequently addressed by health education interventions.10

Health education interventions are comprehensive programmes that healthcare providers deliver to patients aimed at improving patients’ clinical outcomes through the increase and maintenance of health behaviours.11 Along with education about, for example, medication taking, these programmes seek to increase behaviours such as physical exercise and a healthy diet thus reducing patient morbidity or mortality.11 Most diabetes education is provided through programmes within outpatient services or physicians’ practices.12 Many recent education programmes have been designed to meet national or international education standards13–15 with diabetes education being individualised to consider patients’ existing needs and health conditions.16 Patients with T2DM have reported feelings of hopelessness and fatigue with low levels of self-efficacy, after experiencing an acute coronary episode.17

Although there are numerous systematic reviews of educational interventions relating to ACS or T2DM, an umbrella review providing direction on educational interventions for high-risk patients with both ACS and T2DM is not available, indicating a need to gather the current evidence and develop an optimal protocol for health education programmes for patients with ACS and T2DM. This umbrella review will examine the best available evidence on health education-related interventions for patients with ACS or T2DM. We will synthesise these findings to provide direction for health education-related interventions for high-risk patients with both ACS and T2DM.

An umbrella review is a new method to summarise and synthesise the evidence from multiple systematic reviews/meta-analyses into one accessible publication.18 Our aim is to systematically gather, evaluate and organise the current evidence relating the health education interventions for patients with ACS or T2DM, and proffer recommendations for the scope of educational content and delivery methods that would be suitable for patients with ACS and T2DM.

Methods

Data sources

This umbrella review performed a literature search to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining health education-related interventions for patients with ACS or T2DM. The search strategies are described in online supplementary appendix 1. This umbrella review searched eight databases for articles published from January 2000 to May 2016: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs Institute, Journals@Ovid, EMBase, Medline, PubMed and Web of Science. The search was limited to English language only. The following broad MeSH terms were used: acute coronary syndrome; angina, unstable; angina pectoris; coronary artery disease; coronary artery bypass; myocardial infarction; diabetes mellitus, type two; counseling; health education; patient education as topic; meta-analysis (publication type); and meta-analysis as a topic.

bmjopen-2017-016857supp001.pdf (5.1MB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

Participants

All participants were diagnosed with ACS or T2DM using valid, established diagnostic criteria. The diagnostic standards included those described by the American College of Cardiology or American Heart Association,3 National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand,19 WHO20 or other associations.

Intervention types

For this umbrella review, health education-related interventions refer to any planned activities or programmes that include behaviour modification, counselling and teaching interventions. Results considered for this review included changes in clinical outcomes (including BP levels, body weight, diabetes complications, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), lipid levels, mortality rate and physical activity levels), behavioural outcomes (such as diet, knowledge, self-management skills, self-efficacy and smoking), psychosocial outcomes (such as anxiety, depression, quality of life and stress) and medical service use (such as medication use, healthcare utilisation and cost-effectiveness) for patients with ACS or T2DM. These activities or programmes included any educational interventions delivered to patients with ACS or T2DM. The interventions are delivered in any format, including face-to-face, telephone and group-based or one-on-one, and the settings include community, hospital and home. The interventions were delivered by nurses (including diabetes nurse educators), physicians, community healthcare workers, dietitians, lay people, rehabilitation therapists or multidisciplinary teams.

Study types

Only systematic reviews and meta-analyses were included in this review.

Eligibility assessment

The title and abstract of all of the retrieved articles were assessed independently by two reviewers (XL-L, YS) based on the inclusion criteria. All duplicate articles were identified within EndNote V.X721 and subsequently excluded. If the information from the titles and abstract was not clear, the full articles were retrieved. The decision to include an article was based on an appraisal of the full text of all retrieved articles. Any disagreements during this process were settled by discussion and, if necessary, consensus was sought with a third reviewer. We developed an assessment form in which specific reasons for exclusion were detailed.

Assessment of methodological quality

The methodological quality and risk of bias were assessed for each of the included publications using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR),22 independently by the same two reviewers (see table 1). The AMSTAR is an 11-item tool, with each item provided a score of 1 (specific criterion is met) or 0 (specific criterion is not met, unclear or not applicable).22 23 An overall score for the review methodological quality is then calculated as the sum of the individual item scores: high quality, 8–11; medium quality, 4–7 or low quality, 0–3.23 If the required data were not available in the article, the original authors were contacted for more information. The low quality reviews (AMSTAR scale: 0–3) were excluded in this umbrella review.

Table 1.

Methodological quality assessment of included systematic reviews and meta-analyses

| Systematic review/ meta-analysis |

Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Total score | |

| Systematic reviews and meta-analysis involved patients with ACS | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Barth et al69 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| 2 | Devi et al44 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | 10 |

| 3 | Ghisi et al50 | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 7 |

| 4 | Kotb et al59 | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| 5 | Brown et al37 | Yes | No | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | 7 |

| 6 | Dickens et al45 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 7 | Aldcroft et al31 | CA | No | Yes | CA | NO | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| 8 | Brown et al70 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | 10 |

| 9 | Huttunen-Lenz et al56 | CA | No | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 5 |

| 10 | Goulding et al51 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| 11 | Auer et al34 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| 12 | Barth et al36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| 13 | Fernandez et al48 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 8 |

| 14 | Barth et al35 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 15 | Clark et al41 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Systematic reviews and meta-analysis involved patients with T2DM | |||||||||||||

| 16 | Choi et al40 | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 17 | Creamer et al42 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| 18 | Huang et al55 | CA | CA | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 19 | Chen et al39 | CA | CA | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 20 | Pillay et al71 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| 21 | Terranova et al72 | CA | CA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 22 | Attridge et al33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 10 |

| 23 | Odnoletkova et al66 | Yes | CA | Yes | CA | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| 24 | Pal et al67 | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| 25 | Ricci-Cabello et al73 | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| 26 | Saffari et al74 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 27 | Gucciardi et al52 | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| 28 | Pal et al68 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 10 |

| 29 | van Vugt et al75 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Yes | 6 |

| 30 | Amaeshi32 | CA | CA | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | No | No | 4 |

| 31 | Nam et al62 | CA | CA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 32 | Steinsbekk et al76 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| 33 | Burke et al38 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | 10 |

| 34 | Lun Gan et al57 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| 35 | Ramadas et al77 | CA | CA | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Yes | 5 |

| 36 | Hawthorne et al54 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | 8 |

| 37 | Minet et al61 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| 38 | Alam et al30 | Yes | Yes | No | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 39 | Duke et al46 | Yes | CA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| 40 | Fan and Sidani47 | Yes | No | Yes | CA | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 5 |

| 41 | Hawthorne et al53 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| 42 | Khunti et al58 | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 5 |

| 43 | Loveman et al60 | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| 44 | Wens et al78 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | 7 |

| 45 | Nield et al63 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 9 |

| 46 | Zabaleta and Forbes79 | CA | CA | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | No | No | 5 |

| 47 | Deakin et al43 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| 48 | Vermeire et al80 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 9 |

| 49 | Gary et al49 | CA | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| 50 | Norris et al65 | CA | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | No | No | 4 |

| 51 | Norris et al64 | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | No | No | 5 |

Item 1: ‘Was an "a priori" design provided?’,Source:Shea et al22; Item 2: ‘Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction?’; Item 3: ‘Was a comprehensive literature search performed?’; Item 4: ‘Was the status of publication (ie, grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion?’; Item 5: ‘Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided?’; Item 6: ‘Were the characteristics of the included studies provided?’; Item 7: ‘Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented?’; Item 8: ‘Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions?’; Item 9: ‘Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate?’; Item 10: ‘Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed?’; Item 11: ‘Was the conflict of interest stated?’

CA, cannot answer; NA, not applicable.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers using a predefined data extraction form. For missing or unclear information, the primary authors were contacted for clarification.

Statistical presentation of results from reviews

All of the results were extracted for each included systematic review or meta-analysis, and the overall effect estimates are presented in a tabular form. The number of systematic reviews or meta-analyses that reported the outcome, total sample (from included publications) and information of health education interventions is also presented in tables 2 and 3.24 A final ‘summary of evidence’ was developed to present the intervention, included study synthesis, and indication of the findings from the included papers (table 4).24 This umbrella review calculated the corrected covered area (CCA) (see online supplementary appendices 2 and 3). The CCA statistic is a measure of overlap of trials (the repeated inclusion of the same trial in subsequent systematic reviews included in an umbrella systematic review). A detailed description of the calculation is provided by the authors who note slight CCA as 0%–5%, moderate CCA as 6%–10%, high CCA as 11%–15% and very high CCA is >15%.25 The lower the CCA the lower the likelihood of overlap of trials included in the umbrella review.

Table 2.

Characteristics and interventions of included systematic reviews and meta-analysis involved patients with ACS

| First author, year; journal | Primary objectives (to assess effect of interventions on….) |

Studies details | Intervention |

Outcomes

(primary outcomes were in bold) ‘−': No change ‘↑': Increase ‘↓': Decrease |

Synthesis methods | |||||

| Educational content | Provider | Number of session(s), delivery mode, time, setting | ||||||||

| Devi, 201544; The Cochrane Library | Lifestyle changes and medicines management |

Number of studies: 11 completed trials (12 publications); Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1392 participants |

All internet-based interventions |

√ BEHA (-) √ CVR (-) √ DIET (-) √ EXERCISE (-) □ MED √ PSY(-) √ SMOKING (-) □ SELF |

Dietitians; exercise specialists; nurse practitioners; physiotherapist rehabilitation specialists, or did not describe. |

Number of session: weekly or monthly or unclear; Total contact hours: unclear. Duration: from 6 weeks to 1 year |

Strategies: internet-based and mobile phone-based intervention, such as email access, private-messaging function on the website, one-to-one chat facility, a synchronised group chat, an online discussion forum, or telephone consultations; or video files; Format: one-on-one chat sessions; ‘ask an expert’ group chat sessions; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

− Clinical outcomes; − Cardiovascular risk factors;

− Lifestyle changes; − Compliance with medication; − Healthcare utilisation and costs; ↓ Adverse intervention effects |

Meta-analysis used Review Manager software |

| Barth, 201569; The Cochrane Library | Smoking cessation |

Number of studies:40 RCTs; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 7928 participants |

Psychosocial smoking cessation interventions | □ BEHA □ CVR □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED □ PSY √ SMOKING □ SELF |

Cardiologist; general practitioner physician or study nurse |

Number of session: weekly or 2–3 times per week; Total contact hours: unclear. Duration: from 8 weeks to 1 year |

Strategies: face-to-face, telephone contact, written educational materials, videotape, booklet or unclear; Format: one by one counselling; telephone call; group meetings or unclear; Theoretical approach: TTM, SCT |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other | ↑ Abstinence by self-report or validated | Meta- analysis used Review Manager software |

| Kotb, 201459; PLoS One | Patients’ outcomes |

Number of studies: 26 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 4081 participants |

Telephone-delivered postdischarge interventions | □ BEHA √ CVR □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Dietitians; exercise specialist; health educators; nurses and pharmacists |

Number of session: 3–6 sessions/telephone calls and was greater than six calls in five studies; or unclear; Total contact hours: 40 –180 mins or unclear; Duration: 1.5–6 months or unclear |

Strategies: telephone calls; Format: unclear, did not describe the format; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe the setting |

↓ All-cause hospitalisation;

− All-cause mortality; ↓ Depression; − Anxiety; ↑ Smoking cessation, ↓ Systolic blood pressure; − LDL-c |

Meta- analysis used Review Manager software |

| Ghisi, 201450; Patient Education and Counseling | Knowledge, health behaviour change, medication adherence, psychosocial well-being |

Number of studies: 42 articles; Types of studies: 30 were experimental: 23 RCTs and 7 quasi-experimental; and 11 observational and 1 used a mixed-methods design. Total sample: 16 079 participants |

Any educational interventions |

√ BEHA (+) √ CVR (++) √ DIET (+++) √ EXERCISE (++) √ MED (++) √ PSY(++) √ SMOKING (+) □ SELF |

Nurses (35.7%), a multidisciplinary team (31%), dietitians (14.3%) and a cardiologist (2.4%) |

Number of session: 1–24 or unclear. Total contact hours: 5–10 min to 3 hours as well as a full day of education Duration: 1–24 month; from daily education to every 6 months |

Strategies: did not describe the strategies; Format: group (88.1%) education was delivered by lectures (40.5%), group discussions (40.5%) and question and answer periods (7.1%). Individual education (88.1%), including individual counselling (50%), follow-up telephone contacts (31%) and home visits (7.1%); Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings |

− Knowledge;

− Behaviour; − Psychosocial indicators |

Narrative synthesis |

| Brown, 201337; European Journal of Preventive Cardiology | Mortality, morbidity, HRQoL and healthcare costs |

Number of studies: 24 papers reporting on 13 RCTs; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 68 556 participants |

Patient education | □ BEHA √ CVR □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Nurses or other healthcare professionals. |

Number of session and duration: from a total of 2 visits to a 4 -week residential stay reinforced with 11 months of nurse led follow-up Total contact hours: unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face education sessions, telephone contact and interactive use of the internet; Format: group-based sessions, individualised education and four used a mixture of both sessions; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, other |

− Mortality,

− Non-fatal MI, − Revascularisations, − Hospitalisations, − HRQoL, − Withdrawals/dropouts; − Healthcare utilisation and costs |

Meta- analysis used Review Manager software |

| Dickens, 201345; Psychosomatic Medicine | Depression and depressive symptoms |

Number of studies: 62 independent studies Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 17 397 |

Psychological interventions |

√ BEHA (-) □ CVR □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

A single health professional or by a unidisciplinary team |

Number of session: 14.4 (range, 1–156); Total contact hours: varying from 10 to 240 min Duration: unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face sessions, telephone contact or unclear; Format: group or unclear; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe |

↓ Depression;

− Adverse cardiac outcomes; − Ongoing cardiac symptoms |

Univariate analyses using comprehensive meta-analysis, multivariate meta-regression using SPSS V.15.0 |

| Aldcroft, 201120; Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation & Prevention | Health behaviour change |

Number of studies: seven trials Types of studies: six randomised controlled trials and a quasi-experimental trial Total sample: 536 participants |

All psychoeducational or behavioural intervention | □ BEHA √ CVR (-) □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Appropriately trained healthcare workers |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 2–12 months |

Strategies: did not describe the strategies; Format: group setting, combination of group and one-on-one education and one-on-one format only; Theoretical approach: TTM, interactionist role theory, Bandura’s self-efficacy theory, Gordon’s relapse prevention model and a cognitive behavioural approach |

Unclear, did not describe |

↓ Smoking rates; medication use;

− Supplemental oxygen use; ↑ Physical activity; ↑ Nutritional habits |

Meta-analysis and narrative presentation |

| Brown, 201170; The Cochrane Library | Mortality, morbidity, HRQoL and healthcare costs |

Number of studies: 24 papers reporting on 13 studies. Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 68 556 participants |

Patient education |

√ BEHA (-) √ CVR (-) □ DIET √ EXERCISE (-) √ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Nurse or did not describe |

Number of session and duration: two visits to 4 weeks residential 11 months of nurse led follow-up Total contact hours: unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face sessions, telephone contact and interactive use of the internet; Format: four studies involved group sessions, five involved individualised education and three used both session types, with one study comparing the two approaches; Theoretical approach: did not describe |

Postdischarge, other |

− Total mortality;

− Cardiovascular − mortality; − Non-cardiovascular mortality; − Total cardiovascular (CV) events; − Fatal and/or non-fatal MI; − Other fatal and/or non-fatal CV events |

Meta-analysis used Review Manager software |

| Goulding, 201051; Journal of Advanced Nursing | Change maladaptive illness |

Number of studies: 13 studies;

Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Interventions to change maladaptive illness beliefs |

√ BEHA (-) □ CVR DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Cardiologist, nurse, psychologist or did not describe. |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 4 days to 2 weeks or unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face sessions, telephone contact and written self-administered; Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: Common Sense Model, Leventhal’s framework |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

− Beliefs (or other illness cognition);

− QoL; − Behaviour; − Anxiety or depression; − Psychological well-being; − Modifiable risk factors; protective factors |

A descriptive data synthesis |

| Huttunen-Lenz, 201056; British Journal of Health Psychology | Smoking cessation |

Number of studies: a total of 14 studies were included Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1792 participants |

Psychoeducational cardiac rehabilitation intervention | □ BEHA □ CVR □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED □ PSY √ SMOKING (-) □ SELF |

Cardiologist, nurse psychologist or did not describe |

Number of session: 4–20 or unclear. Total contact hours: 10–720 mins or unclear Duration: 4–29 weeks or unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face counselling, self-help materials; home visit, booklet, video and telephone contact Format: individual or unclear Theoretical approach: social learning theory; ASE model; TTM; behavioural multicomponent approach |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↑ Prevalent smoking cessation,

↑ Continuous smoking cessation, − Mortality |

Subgroup meta-analysis was used software |

| Auer, 200834; Circulation | Multiple cardiovascular risk factors and all-cause mortality |

Number of studies: 27 articles reporting 26 studies Types of studies: 16 clinical controlled trials and 10 before-after studies Total sample: 2467 patients in CCTs and 38, 581 patients in before-after studies |

In-hospital multidimensional interventions of secondary prevention | □ BEHA □ CVR √ DIET (-) √ EXERCISE (-) √ MED √ PSY (-) √ SMOKING (-) □ SELF |

Cardiac nurses; physician, or did not describe |

Number of session: 1–5 or unclear; Total contact hours: 30–240 mins or unclear; Duration: 4 weeks–12 months |

Strategies: Written material; audiotapes; presentations; face-to-face; Format: group or unclear; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings |

↓ All-cause mortality;

↓ Readmission rates; − Reinfarction rates |

Stata V.9.1 |

| Barth, 200836; The Cochrane Library |

Smoking cessation |

Number of studies: 40 trials; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 7682 patients |

Psychosocial intervention |

√ BEHA (+++) √ CVR (++) □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED √ PSY (+) √ SMOKING (+++) √ SELF(+++) |

Cardiologist, nurse, physician or study nurse |

Number of session: 1–5 or unclear; Total contact hours: 15 mins–9 hours Duration: within 4 weeks or did not report on the duration |

Strategies: face-to-face; information booklets, audiotapes or videotapes Format: group sessions or individual counselling; Theoretical approach: TTM |

Inpatient settings | ↑ Abstinence by self-report or validated | Meta-analysis used Review Manager software |

| Fernandez, 200748; International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare | Risk factor modification |

Number of studies: 17 trials; Types of studies: randomised, quasi-RCTs and clustered trials; Total sample: 4725 participants |

Brief structured intervention |

√ BEHA (-) □√ CVR (-) □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Case manager; dieticians; health educator; nurses; psychologist; and research assistants |

Number of session: supportive counselling ranged from 1 to 7 calls for the duration of the study; Total contact hours: varied from 10 to 30 mins; Duration: unclear |

Strategies: written, visual, audio, telephone contact; Format: did not describe; Theoretical approach: theoretical behaviour change principles |

Unclear, did not describe |

↓ Smoking;

− Cholesterol level; − Physical activity; ↑ Dietary habits; ↓ Blood sugar levels; − BP levels; ↓ BMI; − Incidence of admission |

Cochrane statistical package Review Manager |

| Barth, 200635; Annals of Behavioural Medicine | Smoking cessation |

Number of studies: 19 trials; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 2548 patients |

Psychosocial interventions |

√ BEHA (+++) √ CVR (++) □ DIET □ EXERCISE □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (+++) |

Unclear, did not describe |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face, telephone contact or unclear; Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe |

↑ Abstinence;

↓ Smoking status |

Data analyses were carried out in Review Manager V.4.2 |

| Clark, 200541; Annals of Internal Medicine | Mortality, MI |

Number of studies: 63 randomised trials; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 21 295 patients |

Secondary prevention programmes | □ BEHA □ CVR √ DIET (-) √ EXERCISE (-) □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Nurse, multidisciplinary team or did not describe |

Number of session: 1–12 or unclear Total contact hours: did not describe Duration: 0.75–48 months |

Strategies: face-to-face, telephone contact and home visit; Format: group and individual or unclear; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↓ Mortality,

↓ MI, − Hospitalisation rates |

Performed analyses by using Review Manager V.4.2 and Qualitative Data Synthesis |

Smoking, smoking cessation; CVR, cardiovascular risk factors; PSY, psychosocial issues (depression, anxiety); DIET, diet; EXERCISE, exercise; MED, medication; BEHA, behavioural charge (including lifestyle modification); SELF, self-management (including problems solving); DR, diabetes risks; CHD, coronary heart disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHW, community health worker; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; BP, blood pressure; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SMS, short message service; BCTs, behavioural change techniques; LEA, lower extremity amputation; PRIDE, Problem Identification, Researching one’s routine, Identifying a management goal, Developing a plan to reach it, Expressing one’s reactions and Establishing rewards for making progress; ASE, attitude social influence-efficacy; CVRF, cardiovascular risk factors; PA, physical activity; EDU, patient education; GP, general practice; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; CCTS, controlled clinical trials; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; QoL, quality of life; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TTM, transtheoretical model; SCT, social cognitive theory; HBM, health belief model; SAT, social action theory.

In the educational content: ‘+’: minor focus; ‘++’:moderate focus; ‘+++’ major focus; ‘- ’=unclear what the intensity of the education was for any topic.

In the outcomes: arrow up (‘↑’) for improvement, arrow down (‘↓’) for reduction; a dash (‘−’) for no change or inconclusive evidence. Primary outcomes were in bold.

Table 3.

Characteristics and interventions of included systematic reviews and meta-analysis involved patients with T2DM

| First author, year; journal |

Primary objectives

(to assess effect of interventions on….) |

Studies details | Intervention |

Outcomes

(primary outcomes were in bold.) ‘−': No change ‘↑': Increase ‘↓': Decrease |

Synthesis methods | |||||

| Educational content | Provider | Number of session(s), delivery mode, time, setting | ||||||||

| Choi, 201640; Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice | Glycaemic effect |

Number of studies: 53 studies (5 in English, 48 in Chinese); Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Diabetes education intervention | □ BEHA √ DIET (-) □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Unclear, did not describe |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 30–150 min or unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face, written materials; telephone contact and home visit; Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, post discharge, other | ↓ HbA1cSTATA V.12 and Review Manager V.5.3 | |

| Creamer, 201642; Diabetic Medicine | Successful outcomes and to suggest directions for future research |

Number of studies: 33;

Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 7453 participants |

Culturally appropriate health education |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) √ DR (-) √ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

CHWs, clinical pharmacists dieticians, nurses, podiatrists, physiotherapists and psychologists |

Number of session: 1–10 or unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: from a single session to 24 months |

Strategies: face-to-face; phone contact; Format: group sessions (10 studies), individual sessions (13) or a combination of both; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↓ HbA1c,

− HRQoL, − Adverse events, − BP, − BMI, − Lipid levels, − Diabetes complications, − Economic analyses, mortality and diabetes knowledge, − Empowerment, − Self-efficacy and satisfaction |

Meta-analysis using the Review Manager statistical programme |

| Huang, 201655; European Journal of Internal Medicine | Clinical markers of cardiovascular disease |

Number of studies: 17 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Lifestyle interventions | □ BEHA √ DIET (-) √ CVR (-) √ EXERCISE (-) □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Nurse, pharmacist or unclear |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 6 months–8 years |

Strategies: unclear; Format: individual; group and mixed Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe |

Cardiovascular risk factors such as, − BMI, ↓ HbA1c, − BP, ↓ Level of cholesterol |

Review Manager V.5.1 |

| Chen, 201539; Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental | Clinical markers |

Number of studies: 16 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: per study ranged from 23 to 2575 |

Lifestyle intervention |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET √ CVR (-) □ EXERCISE □ GC √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Unclear, did not describe |

Number of session: monthly; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: <6 months−8 years |

Strategies: unclear; Format: individual; group and mixed; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe |

Cardiovascular risk factors including ↓ BMI, ↓ HbA1c, ↓ SBP, DBP, − HDL-c and LDL-c |

All analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis statistical software |

| Terranova, 201572; Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism |

Weight loss |

Number of studies: 10 individual studies (from 13 papers); Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: ranging from 27 to 5145 participants |

Lifestyle-based-only intervention |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR (-) √ EXERCISE (-) □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Dietician; diabetes educator; general physician; multidisciplinary team or nutritionist; nurse |

Number of session: 1–42; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: ranged from 16 weeks to 9 years |

Strategies and format: face-to-face individual or group-based sessions, or a combination of those. One study delivered the intervention via the telephone Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe |

↓ Weight change;

− HbA1c |

Meta-analyses—Review Manager and meta-regression analysis—Stata version. |

| Pillay, 201571; Annals of Internal Medicine | HbAIc level |

Number of studies: 132; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Behavioural programme |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Trained individuals |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: range, 7–40.5 hours; Duration: 4 or more weeks |

Strategies: unclear; Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, post discharge, other |

− HbA1c;

↓ BMI |

The analysis was conducted by using a Bayesian network model |

| Pal, 201467; Diabetes Care | Health status, cardiovascular risk factors and QoL |

Number of studies: 20 papers describing 16 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 3578 participants |

Computer-based self-management interventions | □ BEHA □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF |

Unclear, did not describe |

Number of session: 1–8; Total contact hours: 10 min– 6 hours; Duration: 8 weeks–12 months |

Strategies: online/web-based; Phone contact Format: individual; group and mixed Theoretical approach: TTM, social ecological theory, SCT and self-determination theory |

Unclear, did not describe |

− HRQoL,

↓HbA1c, − Death; ↓Cognitions, behaviours, −Social support, ↓Cardiovascular risk factors, −Complications, −Emotional outcomes, −Hypoglycaemia, −Adverse effects, −CE and economic data |

Meta-analysis using Review Manager software or narrative presentation |

| Ricci-Cabello, 201473; BMC Endocrine Disorders | Knowledge, behaviours and clinical outcomes |

Number of studies: 37 studies; Types of studies: almost two-thirds of the studies were RCTs, 27% studies were quasi-experimental design. Total sample: unclear |

DSM educational programme | □ BEHA √ DIET(+++) □ DR √ EXERCISE (+++) √ GC(+++) √ MED(++) √ PSY(++) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Dietitian; nurse; psychologist; physician; research team or staff |

Number of session: 13.1; Total contact hours: 0.25–180 hours; Duration: 0.25–48 months |

Strategies: face-to-face; telecommunication; both Format: one on one; group and mixed Theoretical approach: unclear |

Postdischarge, other |

−Diabetes knowledge;

−Self-management; −Behaviours; −Clinical outcomes; ↓Glycated haemoglobin; −Cost-effectiveness analysis |

Meta-analyses and bivariate meta-regression were conducted with Stata V.12.0 |

| Saffari, 201474; Primary Care Diabetes | Glycaemic control. |

Number of studies: 10; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 960 patients |

An educational intervention using SMS |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE √ GC (-) √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Unclear, did not describe |

Number of session: weekly; or two messages daily or unclear; Total contact hours: unclear. Duration: 3 months–1 year |

Strategies: SMS: sending and receiving data. Receive data through text-messaging by patients only. Used a website along with SMS; Format: Unclear; Theoretical approach: Unclear. |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other | ↑Glycaemic control | Comprehensive Meta-analysis Software V.2.0 |

| Odnoletkova, 201466; Journal of Diabetes & Metabolism | Cost-effectiveness (CE) |

Number of studies: 17 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Therapeutic education |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

General physician; nutritionists or unclear |

Number of session: ~16; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face or unclear; Format: individual and group lessons; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inhospital or unclear | −CE | Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio |

| Attridge, 201433; The Cochrane Library | HbAIc level, knowledge and clinical outcomes |

Number of studies: 33 trials; Types of studies: RCTs and quasi-RCTs; Total sample: 7453 participants |

’Culturally appropriate' health education |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) □ MED □ PSY √ SMOKING (-) □ SELF |

CHWs; dieticians; exercise physiologists; lay workers; nurses; podiatrists and psychologists |

Number of session: one session to 24 months; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: the median duration of interventions was 6 months |

Strategies:

Format: group intervention method, one-to-one sessions and a mixture of the two methods. Or a purely interactive patient-centred method Theoretical approach: empowerment theories; behaviour change theories, TTM of behaviour change and SCT |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↓HbA1c;

−HRQoL; −Adverse events; −Mortality; −Complications; −Satisfaction; ↑Empowerment; ↑Self-efficacy; −Attitude; knowledge; −BP; −BMI; ↓Lipid levels; −Health economics |

Meta-analyses used Review Manager software |

| Vugt, 201375; Journal of Medical Internet Research | Health outcomes |

Number of studies: 13 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 3813 patients |

BCTs are being used in online self-management interventions |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Healthcare professional |

Number of session: 6 weekly sessions or unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: unclear |

Strategies: online/web-based; Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: self-efficacy theory, social support theory, TTM, SCT, social-ecological model and cognitive behavioural therapy |

Postdischarge |

−Health behaviour change;

−Psychological well-being; −Clinical parameters |

Unclear |

| Gucciardi, 201352; Patient Education and Counseling | HbAIc level,physical activity and diet outcomes |

Number of studies: 13 studies; Types of studies: RCTs and comparative studies; Total sample: unclear |

DSME interventions. | □ BEHA √ DIET (+++); □ DR √ EXERCISE (+++); □ GC √ MED (+); √ PSY (+) □ SMOKING √ SELF (++) |

Dietitians (n=7/13); Multidisciplinary team (n=7/13); Nurse (n=5/13); Community peer worker (n=3/13) |

Number of session: low intensity: <10 education sessions (n=7); high intensity: ≥10 education sessions (n=6); Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: <6 months (n=7/13); ≥6 months (n=6/13) |

Strategies: face-to-face (n=13/13); written literature: (eg, handbook) (n=4/13); telephone (n=4/13); audiovisual (n=1/13) Format: one-on-one: (n=11/13); group (n=9/13) Theoretical approach: SAT; empowerment Behaviour change model; modification theories; pharmaceutical care model; Behaviour change theory; PATHWAYS programme; symptom- focused management model; motivational interviewing |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge |

− HbA1c levels,

− Anthropometrics, − Physical activity; − Diet outcomes |

A recently described method |

| Pal, 201368; The Cochrane Library | Health status and HRQoL |

Number of studies: 16 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 3578 participants |

Computer-based diabetes self-management intervention | □ BEHA √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) √ MED (-) √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Nurse or other healthcare professionals |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 1 session– 18 months |

Strategies: online/web-based; phone contact Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

− HRQoL;

− Death from any cause; ↓HbA1c; − Cognitions; − Behaviours; −Social support; −Biological markers; − Complications |

Formal meta-analyses and narrative synthesis |

| Nam, 201262; Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing | Glycaemic control |

Number of studies: 12 RCTs; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1495 participants |

Diabetes educational interventions (no drug intervention) | □ BEHA √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) √ MED (-) √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Nurses (36%), dieticians (36%), diabetes educators (5%), other professionals (9%) and non-professional staff (14%) |

Number of session: 1 month or less; 1–3 months and 12 months; Total contact hours: most studies did not describe, or from 1 session to more than 30 hours; Duration: from 1 session to 12 months, frequency: 1 session to 25 weekly or biweekly education |

Strategies: teaching or counselling; home-based support and visual aids Format: group education or a combination of group education and individual counselling; or only individual counselling; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other | ↓HbA1c level | Meta-analysis |

| Steinsbekk, 201276; BMC Health Services Research | Clinical, lifestyle and psychosocial outcomes |

Number of studies: 21 studies (26 publications) Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 2833 participants |

Group-based education | Did not describe the content of the intervention | Community workers; dietician; lay health advisors nurse and nutritionist |

Number of session and total contact hours: 30 hours over 2.5 months, 52 hours over 1 year and 36 or 96 hours over 6 months Duration: 6 months to 2 years |

Strategies: face-to-face; Format: 5 to 8 participants group to 40 patients group Theoretical approach: empowerment model and the discovery learning theory, the SCT and the social ecological theory, the self-efficacy and self-management theories and operant reinforcement theory |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↓HbA1c,

↑Lifestyle outcomes, ↑Diabetes knowledge, ↑Self-management skills, ↑Psychosocial outcomes, ↓Mortality rate, ↓BMI, ↓Blood pressure; ↓Lipid profile |

Meta-analysis using Review Manager V.5 |

| Amaeshi, 201232; Podiatry Now | Increasing good foot health practices that will ultimately reduce LEA |

Number of studies: eight studies; Types of studies: RCT or clinical controlled trial (CCT); Total sample: unclear |

Foot health education | Food care | Podiatrist, psychologist or unclear |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: between 15 min and 14 hours; Duration: 3–30 months |

Strategies: face- to-face; Format: in three of the studies, educational interventions were delivered to the participants in groups, while the other five provided individualised (one-to-one) foot care education to the participants; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe |

↓ LEA;

↑Self-care |

Narrative synthesis |

| Lun Gan, 201157; JBI Library of Systematic Reviews |

Oral hypoglycaemic adherence |

Number of studies: seven studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Educational interventions |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) √ MED (-) √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Nurses; pharmacists; other skilled healthcare professionals |

Number of session: 1–12 or unclear; Total contact hours: 2.5 hours or unclear; Duration: 4–12 months |

Strategies: face- to-face; Format: group and individual; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↓ HbA1c,

− Medication adherence; ↓Blood glucose; − Tablet count; − Medication containers; − Diabetes complications; − Health service utilisation |

Narrative summary form |

| Burke, 201138; JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports | HbAIc level,BP |

Number of studies: 11 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental trials; Types of studies: RCTs and quasi-experimental trials; Total sample: 2240 patients |

Group medical visits |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR □ EXERCISE √ GC (-) √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Endocrinologists; DM nurse; family physician; nutritionist and rehab therapist |

Number of session: 1–4 or unclear; Total contact hours: 2–4 hours or unclear; Duration: 1 session to 2 years |

Strategies: face-to-face; Format: group and individual; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↓HbA1c;

−Systolic and diastolic BP; −LDL measurements |

Meta-analysis |

| Ramadas, 201177; International Journal of Medical Informatics | HbAIc level |

Number of studies: 13 different studies; Types of studies: RCTs and quasi-experimental studies; Total sample: unclear |

Web-based behavioural interventions |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR □ EXERCISE √ GC (-) √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Dietician; endocrinologist; physicians; researchers or research staff members and study nurse |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: ranged between 12 and 52 weeks, with an average of 27.2±18.3 weeks |

Strategies: email and SMS technologies that were commonly used together with the websites to reinforce the intervention, and website, print material Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: Wagner’s Chronic Care Model; self-efficacy theory/social support theory; TTM; HBM; SCT |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

− Self-monitoring blood sugar,

− Weight loss, − Dietary behaviour, − Physical activity |

Not statistically combined and re-analysed |

| Minet, 201061; Patient Education and Counseling | Glycaemic control |

Number of studies: 47 studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Self-care management interventions |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Case nurse manager; group facilitator; nurse educator; multidisciplinary team; physiologist; physician; peer counsellor; researcher and pharmacist |

Number of session: 3–26; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 4 weeks to 4 years |

Strategies: face-to-face; home visit; phone calls; Format: group and individual; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other | ↓ HbA1c | Meta-analyses and meta-regression used Stata’s meta command |

| Hawthorne, 201054; Diabetic Medicine | Effects of culturally appropriate health education |

Number of studies: 10 trials; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1603 patients |

Culturally appropriate health education | □ BEHA √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Exercise physiologists; dieticians; diabetes nurses; link workers and podiatrists |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 1 session to 12 months |

Strategies: face-to-face; visual aids, leaflets and teaching materials; Format: group approach, one-to-one interviews and a mixed approach; Theoretical approach: SAT, Empowerment Behaviour Change Model, SCT, Management model and the Theory of Planned Behaviour |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

−QoL;

↓HbA1c; − BP; ↑Knowledge; − BMI; ↓ Lipid levels, − Diabetic complications, − Mortality rates, hospital admissions, hypoglycaemia |

Meta -analysis using the Review Manager and narrative review |

| Fan, 200947; Canadian Journal of Diabetes | Knowledge, self-management behaviours and metabolic control |

Number of studies: 50 studies;

Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

DSME intervention |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Unclear, did not describe |

Number of session: 10 (range 1–28); Total contact hours: 17 contact hours (range 1– 52); ≤10 (46%); 11–20 (21%); >20 (33%); Duration: 22 weeks (range 1–48); ≤8 weeks (26%); 9–24 weeks (37%); >24 weeks (37%) |

Strategies: Online/web-based (4%); video (2%); face-to-face (60%); phone contact (4%); Mixed (30%). Format: one-on-one (32%); group (40%); mixed (28%) Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other | ↑ Diabetes knowledge,

↑ Self-management behaviours; ↓ HbA1c |

Comprehensive meta-analysis (V.2.0) |

| Duke, 200946; The Cochrane Library | Metabolic control, diabetes knowledge and psychosocial outcomes |

Number of studies: nine studies; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1359 participants |

Individual patient education |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Diabetes educators and dieticians |

Number of session: 1–6; Total contact hours: 20 min –7 hours; Duration: 4 weeks–1 year |

Strategies: face to face; telephone; Format: individual; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings |

− HbA1c;

− Diabetes complications; − Health service utilisation and healthcare costs; − Psychosocial outcomes; − Diabetes knowledge; patient self-care behaviours; − Physical measures; metabolic |

Meta-analysis |

| Alam, 200930; Patient Education and Counseling | Glycaemic control and psychological status |

Number of studies: 35 trials; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1431 patients |

Psycho-educational interventions |

√ BEHA (-) □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Generalists; psychological specialists; or did not report the specialist |

Number of session: 1–16; Total contact hours: 20 min –28 hours; Duration: about 13.7 (±11.06) weeks |

Strategies: face to face; telephone calls; Format: group format; a single format and used a combination; Theoretical approach: TTM; motivational interviewing |

Inpatient settings, other |

↓ HbAlc;

↓ Psychological distress |

Meta-analysis |

| Khunti, 200858; Diabetic Medicine | Knowledge and biomedical outcomes |

Number of studies: nine studies; Types of studies: RCTs and RCT was followed by a before-and-after study; Total sample: 1004 patients |

Any educational intervention | □ BEHA √ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Unclear, did not describe |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 3–12 months |

Strategies: face-to-face; Format: group and individual; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Unclear, did not describe |

− Knowledge;

− Psychological and biomedical outcome measures |

Unclear |

| Loveman, 200860; Health Technology Assessment | Clinical effectiveness. |

Number of studies: 21 published trials; Types of studies: RCTs and CCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Educational interventions |

√ BEHA (++) √ DIET (+++) □ DR √ EXERCISE (+++) √ GC (+++) □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (+++) |

Community workers; diabetes research technician; diabetes nurse, dieticians; educationalist; medical students; nurses; pharmacists; physician or physician assistant |

Number of session: two to four intensive education of 1.5–2 hours followed-up with additional education at, 3 and 6 months; Total contact hours and duration: about 150 mins over 6 months or 61–52 hours over 1 year |

Strategies: face-to-face; Format: group and individual; Theoretical approach: cognitive-behavioural strategies; pedagogical principle |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

− Diabetic control outcomes; − Diabetic end points; − QoL and cognitive measures |

Narrative review |

| Wens, 200878; Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice | Improving adherence to medical treatment recommendations |

Number of studies: eight studies; Types of studies: RCTs and controlling before and after studies Total sample: 772 patients |

Interventions aimed at improving adherence to medical treatment |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Diabetes educator; nurse or did not describe |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration:~9 months or unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face; telephone; Format: face-to-face; group based and telemedicine; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

− Adherence;

− HbA1c; − Blood glucose |

Cochrane Review Manager software |

| Hawthorne, 200853; The Cochrane Library | HbAIc level, knowledge and clinical outcomes |

Number of studies: a total of 11 trials; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1603 patients |

Culturally appropriate (or adapted) health education |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) □ MED □ PSY √ SMOKING (-) □ SELF |

Dieticians, diabetes nurses, exercise physiologists; link workers; podiatrists; psychologist and and non-professional link worker |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: 1 session to 12 months |

Strategies: face-to-face; booklet; Format: group intervention method; one-to-one interviews; mixture of the two methods; purely interactive patient-centred method; semi-structured didactic format and combination of the two approaches Theoretical approach: SAT; Empowerment Behaviour Change Model; Behaviour Change Theory; SCT, Management Model and the Theory of Planned Behaviour |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

↓HbA1c

↑ Knowledge scores − Other outcome measures |

Narrative presentation and meta-analysis |

| Nield, 200763; The Cochrane Library | Metablic control |

Number of studies: 36 articles (18 trials); Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 1467 participants |

Dietary advice | □ BEHA √ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Exercise physiologist; dietitian; group facilitator; nutritionist; nurse educator; and physician |

Number of session: 1–12; Total contact hours: 20 min–22 hours; Duration: 11 weeks– 6 months or unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face; Format: group and individual; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other |

− Weight;

− Diabetic complications; − HbA1c; − QoL; − Medication use; − Cardiovascular disease risk |

Meta-analysis |

| Zabaleta, 200779; British Journal of Community Nursing | Clinical effectiveness |

Number of studies: 21 studies; Types of studies: controlled trials; Total sample: unclear |

Structured group diabetes education |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) □ MED √ PSY (-) □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Diabetes nurse educator; physician’s assistant and physicians |

Number of session: 4–6 or unclear; Total contact hours: 6–12 hours or unclear; Duration: 1–6 months or unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face; Format: group; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Postdischarge | −HbA1c | A tabulative synthesis |

| Deakin, 200543; The Cochrane Library | Clinical, lifestyle and psychosocial outcomes |

Number of studies: 14 publications, reporting 11 studies; Types of studies: RCTs, and CCTs; Total sample: 1532 participants. |

Group-based educational programmes | Did not describe the content of the intervention | Health professionals, lay health advisors |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: from 6 to 52 hours; Duration: 3 hours per year for 2 years and 3 or 4 hours per year for 4 years |

Strategies: unclear; Format: group; Theoretical approach: the Diabetes Treatment and Teaching Programme (DTTP); empowerment model; adult learning model, public health model, HBM and TTM |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge |

↓Metabolic control; ↑Diabetes knowledge;

↑QoL; ↑Empowerment/self-efficacy |

Summarised statistically |

| Vermeire, 200580; The Cochrane Library | Improving adherence to treatment recommendations |

Number of studies: 21 articles; Types of studies: RCTs; cross-over study; controlled trial; controlled before and after studies; Total sample: 4135 patients |

Interventions that were aimed at improving the adherence to treatment recommendations | □ BEHA □ DIET □ DR □ EXERCISE √ GC (-) √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Nurse, pharmacist and other healthcare professionals |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear; Duration: unclear |

Strategies: face-to-face; telephone; home visit; video; mailed educational materials; Format: unclear Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge |

Direct indicators, such as ↓Blood glucose level; − Indirect indicators, such as pill counts; −Health outcomes |

A descriptive review and subgroup meta-analysis |

| Gary, 200349; Diabetes Educator | Body weight and glycaemic control |

Number of studies: 63 RCTs; Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: 2720 patients |

Educational and behavioural component interventions | □ BEHA √ DIET (-) □ DR √ EXERCISE (-) √ GC (-) √ MED (-) □ PSY □ SMOKING □ SELF |

Nurse (39%); dietitian (26%); physician (17%); other or not specified (23%); other professional (13%); psychologist (9%); exercise psychologist (9%) and health educator (4%) |

Number of session: unclear; Total contact hours: unclear. Duration: 1 month to 19.2 months |

Strategies: unclear; Format: unclear; Theoretical approach: SAT, contracting model and patient empowerment |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge |

− Glycaemic control;

− Weight |

Sufficient data were combined using meta-analysis |

| Norris, 200265; Diabetes Care | Total GHb |

Number of studies: 31 studies Types of studies: RCTs. Total sample: 4263 patients |

Self-management education |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

Dietitian; lay healthcare worker; nurse; physician with team; self (eg, computer-assisted instruction) and team (nurse, dietitian, etc) |

Number of session: 6 (1–36); Total contact hours: 9.2 (1–28) hours; Duration: 6 (1.0–27) months |

Strategies: online/web-based; video; face-to-face; phone contact; Format: group; individual and mixed; Theoretical approach: unclear |

Inpatient settings, post discharge, other | ↓Total GHb | Meta-analysis and meta-regression |

| Norris, 200164; Diabetes Care | Clinical outcomes, knowledge, metabolic control |

Number of studies: 72 studies (84 papers); Types of studies: RCTs; Total sample: unclear |

Self-management training interventions |

√ BEHA (-) √ DIET (-) □ DR □ EXERCISE □ GC □ MED □ PSY □ SMOKING √ SELF (-) |

CHWs; nurse; or other healthcare professionals |

Number of session: 1–16; Total contact hours: ~22 hours; Duration: ~26 months |

Strategies: online/web-based; video (2%); face-to-face; phone contact; Format: group; individual and mixed; Theoretical approach: SAT; Fishbein and Ajzen HBM |

Inpatient settings, postdischarge, other | ↑Knowledge;

↑Lifestyle behaviours; −Psychological and QoL outcomes; ↑ Glycaemic control; − Cardiovascular disease risk factors |

Outcomes are summarised in a qualitative fashion |

ASE, attitude social influence-efficacy; BCTs, behavioural change techniques; BEHA, behavioural charge (including lifestyle modification); BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCTS, controlled clinical trials; CHD, coronary heart disease; CHW, community health worker; CVR, cardiovascular risk factors; CVRF, cardiovascular risk factors; DIET, diet; DR, diabetes risks; DSM, diabetes self-management; DSME, diabetes self-management education; EDU, patient education; EXERCISE, exercise; GC, glycaemic regulation; GP, general practice; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HBM, health belief model; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LEA, lower extremity amputation; MED, medication; MI, myocardial infarction; PA, physical activity; PRIDE, Problem Identification, Researching one’s routine, Identifying a management goal, Developing a plan to reach it, Expressing one’s reactions and Establishing rewards for making progress; PSY, psychosocial issues (depression, anxiety); QoL, quality of life; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; SAT, social action theory; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SCT, social cognitive theory; SELF, self-management (including problems solving); SMOKING, smoking cessation; SMS, short message system; T2DM, type two diabetes mellitus; TTM, transtheoretical model.

In the educational content: ‘+’: minor focus; ‘++’:moderate focus; ‘+++’ major focus; ‘- ’=unclear what the intensity of the education was for any topic.

In the outcomes: arrow up (‘↑’) for improvement, arrow down (‘↓’) for reduction; a dash (‘−’) for no change or inconclusive evidence.

Table 4.

Summary of evidence from quantitative research syntheses

| Intervention | Number of systematic reviews/meta-analysis, total participants | First author, year | Primary results/findings | Rating the evidence of effectiveness | |

| Patients with acute coronary syndrome | |||||

| General health education | Six/161 997 patients (Goulding et al, 201051 did not give the total sample size) | Ghisi, 201450 | Knowledge | 91% studies* | Some evidence |

| Behaviour | 77%/84%/65% studies* | ||||

| Psychosocial indicators | 43% studies* | ||||

| Brown, 201337 | Mortality | ||||

| MI | |||||

| Revascularisations | |||||

| Hospitalisations | |||||

| HRQoL | |||||

| Withdrawals/dropouts | |||||

| Healthcare utilisation and costs | |||||

| Brown, 201170 | Total mortality | ||||

| MI | |||||

| CABG | |||||

| Hospitalisations | |||||

| HRQoL | 63.6% studies* | ||||

| Healthcare costs | 40% studies* | ||||

| Withdrawal/dropout | |||||

| Goulding, 201051 | Beliefs | 30.08% studies* | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Fernandez, 200748 | Smoking | ||||

| Cholesterol level | |||||

| Multiple risk factor modification | |||||

| Kotb, 201459 | All-cause hospitalisation | ||||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Smoking cessation | |||||

| Depression | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure | |||||

| Low-density lipoprotein | |||||

| Anxiety | |||||

| Psychoeducational interventions | Six/37 883 patients | Barth, 201569 | Abstinence by self-report or validated | Sufficient evidence | |

| Dickens, 201345 | Depression | ||||

| Aldcroft, 201131 | Smoking cessation | ||||

| Physical activity | |||||

| Huttunen-Lenz,201056 | Prevalent smoking cessation | ||||

| Continuous smoking cessation | |||||

| Total mortality | |||||

| Barth, 200836 | Abstinence by self-report or validated | ||||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Barth, 200635 | Abstinence | ||||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Secondary prevention educational interventions (including Internet-based secondary prevention) | Three/25 154 patients | Devi, 201544 | Mortality | Some evidence | |

| Revascularisation | |||||

| Total cholesterol | |||||

| HDL cholesterol | |||||

| Triglycerides | |||||

| HRQOL | |||||

| Auer, 200834 | All-cause mortality | ||||

| Readmission rates | |||||

| Reinfarction rates | |||||

| Smoking cessation rates | |||||

| Clark, 200541 | Mortality | ||||

| MI | |||||

| Quality of life | Most of the included studies* | ||||

| Patients with T2DM | |||||

| General health education | Five/2319 patients (Choi et al, 201640; Loveman et al, 200860; Zabaleta et al, 200779 did not give the total sample size) | Choi, 201640 | HbA1c | Some evidence | |

| Saffari, 201474 | Glycaemic control | ||||

| Duke, 200946 | HbA1c | ||||

| BP | |||||

| Knowledge, psychosocial outcomes and smoking habits | No data | ||||

| Diabetes complications or health service utilisation and cost analysis | No data | ||||

| Loveman, 200860 | Diabetic control outcomes | 46.15% studies* | |||

| Weight | 66.67% studies* | ||||

| Cholesterol or triglycerides | 40.00% studies (+) | ||||

| Zabaleta, 200779 | HbA1c | 4.8% studies* | |||

| Culturally appropriate health education | Eight/20 622 patients (Ricci-Cabello et al, 201473 and Gucciardi et al, 201352 did not give the total sample size) | Creamer, 201642 | HbA1c | Some evidence | |

| HRQoL | |||||

| AEs | No AEs | ||||

| Ricci-Cabello, 201473 | HbA1c | ||||

| Diabetes knowledge | 73.3% studies* | ||||

| Behaviours | 75% studies* | ||||

| Clinical outcomes | Fasting blood glucose, HbA1c and BP improved in 71%, 59% and 57% of the studies | ||||

| Attridge, 201433 | HbA1c | ||||

| Knowledge scores | |||||

| Clinical outcomes | |||||

| Other outcome measures | Showed neutral effects | ||||

| Gucciardi, 201352 | HbA1c levels | 3 of 10 studies* | |||

| Anthropometrics | 3 of 11 studies* | ||||

| Physical activity | One of five studies* | ||||

| Diet outcomes | Two of six studies* | ||||

| Nam, 201262 | HbA1c level | ||||

| Hawthorne, 201054 | HbA1c | ||||

| Knowledge scores | |||||

| Khunti, 200858 | Knowledge levels | Only one study reporting a significant improvement | |||

| Biomedical outcomes | Only one study reporting a significant improvement | ||||

| Hawthorne, 200853 | HbA1c | ||||

| Knowledge scores | |||||

| Other outcome measures | |||||

| Lifestyle interventions+behavioural programme | Six/10 440 patients (Huang et al, 201655; Pillay et al, 201571 and Ramadas et al, 201177 did not give the total sample size) | Huang, 201655 | HbA1c | Some evidence | |

| BMI | |||||

| LDL-c and HDL-c | |||||

| Chen, 201539 | HbA1c | ||||

| BMI | |||||

| SBP | |||||

| DBP | |||||

| HDL-c | |||||

| Terranova, 201572 | HbA1c level | ||||

| Weight | |||||

| Pillay, 201571 | HbA1c levels | ||||

| BMI | |||||

| Ramadas, 201177 | HbA1c | 46.2% studies * | |||

| Gary, 200349 | Fast blood sugar | ||||

| Glycohaemoglobin | |||||

| HbA1 | |||||

| HbA1c | |||||

| Weight | |||||

| Self-management educational interventions | Nine/19 597 patients (Minet et al, 201061; Fan et al, 200947 and Norris et al, 200164 did not give the total sample size) | Pal, 201467 | Cardiovascular risk factors | Sufficient evidence | |

| Cognitive outcomes | |||||

| Behavioural outcomes | Only one study reporting a significant improvement | ||||

| AEs | No AEs | ||||

| Vugt, 201375 | Health behaviours | 7 of 13 studies * | |||

| Clinical outcomes measures | Nine studies * | ||||

| Psychological outcomes | Nine studies * | ||||

| Pal, 201368 | HbA1c | ||||

| Depression | |||||

| Quality of life | |||||

| Weight | |||||

| Steinsbekk, 201276 | HbA1c | ||||

| Main lifestyle outcomes | |||||

| Main psychosocial outcomes | |||||

| Minet, 201061 | Glycaemic control | ||||

| Fan, 200947 | Diabetes knowledge | ||||

| Overall self-management behaviours | |||||

| Overall metabolic outcomes | |||||

| Overall weighted mean effect sizes | |||||

| Deakin, 200543 | Metabolic control (HbA1c) | ||||

| Fasting blood glucose levels | |||||

| Weight | |||||

| Diabetes knowledge | |||||

| SBP | |||||

| Diabetes medication | |||||

| Norris, 200265 | Total GHb | ||||

| Norris, 200164 | Knowledge | ||||

| Self-monitoring of blood glucose | |||||

| Self-reported dietary habits | |||||

| Glycaemic control | |||||

| Therapeutic education | One/total sample: unclear | Odnoletkova, 201466 | Cost-effectiveness | Overall high in studies on prediabetes and varied in studies on T2DM | Insufficient evidence |

| Foot health education | One/total sample: unclear | Amaeshi32 | Diabetes complications | Some evidence | |

| Incidence of LEA | |||||

| Group medical visit | One/2240 patients | Burke, 201138 | HbA1c | Some evidence | |

| BP and DBP | |||||

| SBP | |||||

| Cholesterol—LDL | |||||

| Psychoeducational intervention | One/1431 patients | Alam, 200930 | HbA1c | Some evidence | |

| Psychological status | |||||

| Interventions aimed at improving adherence to medical treatment recommendations | Three/4907 patients (Lun Gan et al, 201157 did not give the total sample size) | Lun Gan, 201157 | Oral hypoglycaemic adherence | Five of seven studies * | Some evidence |

| Wens et al., 200878 | Adherence | General conclusions could not be drawn | |||

| Vermeire, 200580 | HbA1c | ||||

| Dietary advice | One/1467 patients | Nield, 200763 | Glycaemic control (addition of exercise to dietary advice) | Insufficient evidence to determine | |

| Weight | Limited data | ||||

| Diabetic microvascular and macrovascular diseases | Limited data | ||||

*Intervention group is significantly better than control group, for example, ‘91% studies ’ means 91% studies reported a significant better compared with control group.

AEs, adverse events; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pessure; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HRQoL, health related quality of life; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LEA, lower extremity amputation; MI, myocardial infarction; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; SBP, systolic blood pressure, DBP, diastolic blood pressure, HDL-c, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; T2DM, type two diabetes mellitus.

Synthesising the results and rating the evidence for effectiveness

The statements of evidence were based on a rating scheme to gather and rate the evidence across the included publications.26 The statements of evidence were based on the following rating scheme: sufficient evidence, sufficient data to support decisions about the effect of the health education-related interventions.26 A rating of sufficient evidence in this review is obtained when systematic reviews or meta-analyses with a large number of included articles or participants produce a statistically significant result between the health education group and the control group.26 Some evidence, is a less conclusive finding about the effects of the health education-related interventions26 with statistically significant findings found in only a few included reviews or studies. Insufficient evidence, refers to not enough evidence to make decisions about the effects of the health education-related interventions, such as non-significant results between the health education group and the control group in the included systematic reviews or meta-analyses.26 Insufficient evidence to determine, refers to not enough pooled data to be able to determine whether of the health education-related interventions are effective or not based on the included reviews.26

Results

Characteristics of included reviews