Abstract

Objectives

Treatment failure and poor 5-year survival in mucosal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) has remained unchanged for decades mainly due to advanced stage of presentation and high rates of recurrence. Incomplete surgical removal of the tumour, attributed to lack of reliable methods to delineate the surgical margins, is a major cause of disease recurrence. The predictability of recurrence using immunohistochemistry (IHC) to delineate surgical margins (PRISM) in mucosal HNSCC study aims to redefine margin status by identifying the true extent of the tumour at the molecular level by performing IHC with molecular markers, eukaryotic initiation factor, eIF4Eand tumour suppressor gene, p53, on the surgical margins and test the use of Lugol’s iodine and fluorescence visualisation prior to the wide local excision. This article describes the study protocol at its pre - results stage.

Methods and analysis

PRISM-HNSCC is a bilateral observational research being conducted in Darwin, Australia and Vellore, India. Individuals diagnosed with HNSCC will undergo the routine wide local excision of the tumour followed by histopathological assessment. Tumours with clear surgical margins that satisfy the exclusion criteria will be selected for further staining of the margins with eIF4E and p53 antibodies. Results of IHC staining will be correlated with recurrences in an attempt to predict the risk of disease recurrence. Patients in Darwin will undergo intraoperative staining of the lesion with Lugol’s iodine and fluorescence visualisation to delineate the excision margins while patients in Vellore will not undertake these tests. The outcomes will be analysed.

Ethics and dissemination

The PRISM-HNSCC study was approved by the institutional ethics committees in Darwin (Human Research Ethics Committee 13-2036) and Vellore (Institutional Review Board Min. no. 8967). Outcomes will be disseminated through publications in academic journals and presentations at educational meetings and conferences. It will be presented as dissertation at the Charles Darwin University. We will communicate the study results to both participating sites. Participating sites will communicate results with patients who have indicated an interest in knowing the results.

Trial registration number

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12616000715471).

Keywords: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, surgical margins, immunohistochemistry, p53

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Christian Medical College, Vellore and Royal Darwin Hospital, Darwin patients represent regions with high burden of mucosal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, thus ensuring external validity of the study.

The stringent selection criteria ensure internal validity even though it will impact the sample size at both locations.

Intraoperative methods of staining with Lugol’s iodine and visually enhanced lesion scope examination being done only in Darwin allows us to test the rigour and efficacy of both these methods.

Local disease recurrence usually occurs within 1 year of wide local excision; hence, the follow-up period of a minimum of 1 year is a satisfactory end point to assess this outcome.

Patients may be lost to follow-up in case of death or change of address.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the world with approximately 650 000 new cases reported annually. The vast majority (more than 90%) are head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) that arise from the epithelium lining of the sinonasal tract, oral cavity, pharynx and larynx. HNSCCs are not homogenous; on the contrary, their distinctive molecular genetic profiles have shown them to be heterogeneous that differ in risk factors, pathogenesis and clinical behaviour.1

Despite aggressive treatment regimens with wide surgical excision, radiotherapy and chemotherapy which are all associated with substantial morbidity, the 5-year survival rates for head and neck cancer have not been significantly changed in the last three to four decades. Much of this is attributed to the advanced stage of the disease at presentation, high rates of loco-regional recurrence from inadequate resection ensuing from compromised surgical margins of the tumour and distant metastases. The numerous anatomic sites and the diversity of histological types in these locations also have a contributory role in treatment outcomes.2 3 Hence, early diagnosis and complete resection remain the key to prognosis, recurrence and survival in cancer management.

The completeness of tumour resection is assessed by obtaining tumour-free margins, which is associated with decrease in the rates of recurrence.4 The intraoperative assessment of the tumour margin has conventionally been by naked eye examination and palpation along with available imaging techniques. Vital staining done by applying Lugol’s iodine on the tumour and surrounding area highlights the extent of tumour including premalignant conditions like dysplasia and carcinoma in situ, thus elucidating the surgical margin5 6 which can be completely missed with naked eye observation. The use of visually enhanced lesion scope (VELscope), a simple non-invasive handheld device, allows direct visualisation of alterations such as dysplasia to tissue fluorescence.7

In many institutions, the adequacy of surgical resection of the primary tumour is traditionally determined intraoperatively by histopathological diagnosis of H&E -stained frozen sections of the surgical margins. The formalin-fixed specimens of the excised tumour and remaining frozen section samples of the margins are histologically assessed and have been used as a potential indicator for recurrences and prognosis. However, the predictive ability of histopathological diagnosis alone has proven to be far from satisfactory.8 9 This has been attributed to the undetectable subclinical molecular changes that occur within cells in the proximity of the visible tumour as HNSCC is known to develop second tumours that are multifocal in origin. This phenomenon has been explained by Slaughter et al10 as ‘field cancerisation’ where multiple cell groups independently undergo neoplastic transformation under the stress of regional carcinogenic activity. These genetic alterations may lack the evidence of histopathologic dysplasia and appear to show uninvolved mucosa that account for local recurrence and incomplete surgical resection.1

The initiation and progression of HNSCC is a multistep process that involves progressive acquisition of genetic and epigenetic alterations. Therefore, molecular analysis of surgical margins will perhaps play an increasingly important role in establishing tumour-free surgical margins.8 11 However, most markers lack the sensitivity and ease of applicability for effective clinical use.12 Mutations and overexpression of the tumour suppressor gene p53 are found in 40%–60% of HNSCC.8 13 The eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factor, eIF4E (also known as 4E), has been found to have 100% overexpression in tumours of breast, head and neck and colon.9 Overexpression of eIF4E in more than 5% of the basal cell layer of histologically tumour-free surgical margins of the HNSCC predict significant increase in the risk of recurrence.9 13 Nathan et al13 found a strong correlation between tumour recurrence and overexpression of p53 and eIF4E in histologically tumour-free margins. They concluded that molecular assessment of margins was more reliable than that with routine H&E hence has the potential to guide clinicians in obtaining tumour-free wide margins for complete excision of the lesion.

Objective

The aim of the project is to conduct a prospective follow-up study of patients with head and neck cancer to:

study the expression of the molecular markers p53 and eIF4E by immunohistochemistry (IHC) on histologically tumour-free surgical margins of the excision biopsies of HNSCC in patients from the Royal Darwin Hospital (RDH), Darwin, Australia and Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, India,

determine the correlation of expression of p53 and eIF4E on histologically tumour-free margins with clinical outcomes, such as local recurrence and survival,

determine the sensitivity and specificity of the molecular markers, p53 and eIF4E, on surgical margins in the assessment of adequacy of surgical excision and predictability of recurrence,

study the outcomes of intraoperative use of vital staining and fluorescence visualisation,

determine the epidemiological trend in Darwin and Vellore.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The predictability of recurrence using IHC to delineate surgical margins (PRISM) study is a prospective observational study in two countries Australia and India based at the RDH, Darwin and CMC and Hospital, Vellore.

Sample size

The average number of patients at Darwin and Vellore are 20 and 70 per year, respectively. Most patients present late and obtaining a tumour-free margin is a challenge. We anticipate performing IHC on surgical margins of approximately 50 patients in total—6–8 from Darwin and 40–45 from Vellore.

Target population

All patients diagnosed with mucosal HNSCC at RDH and CMC with a curative intent are potential candidates.

Inclusion criteria

All patients at RDH, Darwin and CMC, Vellore during the recruitment period with a confirmed diagnosis of mucosal HNSCC on initial biopsy.

Wide local excision biopsy with mucosal surgical margins≥5 mm on histopathological examination.

Exclusion criteria

Patients diagnosed with any other histological type of mucosal head and neck cancers.

Wide local excision biopsy specimens with surgical margins that show dysplasia, carcinoma in situ and are positive(<1 mm) and close for invasive tumour (1–5 mm) on histopathological examination.

Patients with metastatic disease except a single regional lymph node with no extracapsular spread.

Patients with main tumour showing perineural and lymphovascular invasion.

Patients with previous radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Patients who undergo postoperative radiotherapy.

Patients in whom the surgical margins of the excision biopsy cannot be defined.

Patients who have been diagnosed with an unknown primary.

Patients under 18 years of age.

Patients who are pregnant at the time of diagnosis.

Patient recruitment

The patient recruitment period is 2 years with a follow-up of minimum 1 year. Recruitment period in Darwin was from November 2013 to November 2015. The follow-up period is until November 2016. In CMC, Vellore, the 2-year recruitment period was from September 2014 to September 2016 with a follow-up of the enrolled patients until September 2017.

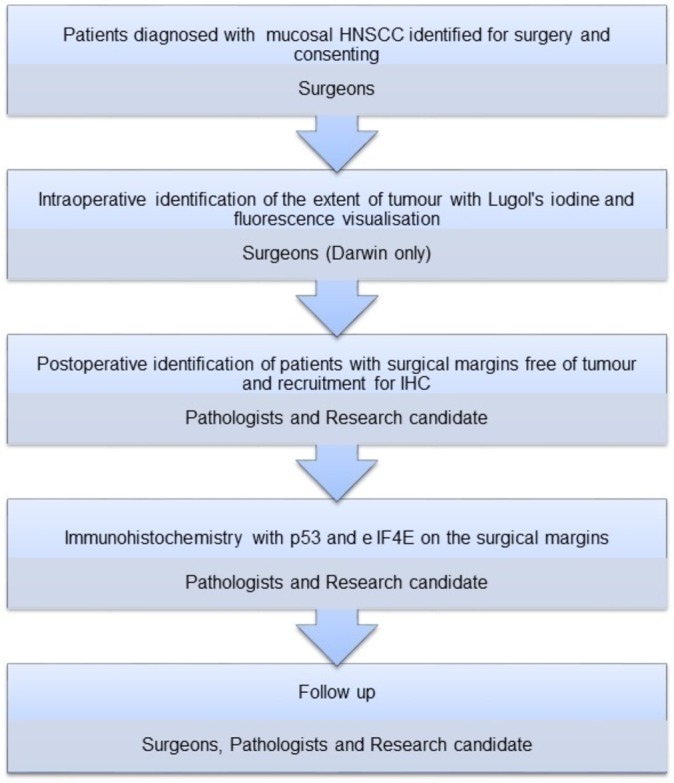

The patients diagnosed to have mucosal HNSCC by clinical evaluation and biopsy at the RDH, Darwin, Australia and CMC and Hospital, Vellore, India will be initially selected based on the selection criteria for the study. All patients will undergo the relevant imaging (CT and/or MRI) tests and an assessment of the eligibility will be determined by using the exclusion criteria. Consent to perform the tests on patients being prepared for excision surgery will be procured by the local site investigators MT (Darwin) and JR (Vellore). (figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flow chart of research activity and the involvement of key personnel. HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Intraoperative assessment

Patients in RDH will undergo a VELscope examination and Lugol’s iodine staining to mark the extent of tumour and identify surgical margins. These tests will not be performed in CMC.

Postoperative assessment

Five surgical margins of the excised tumour will be colour coded using marking ink, labelled with sutures, numbered and photographed. The surgeons at both sites will mark the margins 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 with black, red, blue, green and yellow, respectively.

Paraffin sections from the primary tumour and all the surgical margins will be routinely reported by the resident pathologists at the Pathology Department at RDH, Darwin and Department of Pathology at CMC, Vellore. The patients with histologically tumour-free margins that satisfy the selection criteria will finally be included for further analysis by IHC using p53 and eIF4E antibodies on the mucosal margins. An excision margin is free of tumour when it is ≥5 mm away from the tumour. Coauthors SM and/or MeT will countercheck the eligibility criteria of the sections selected for IHC.

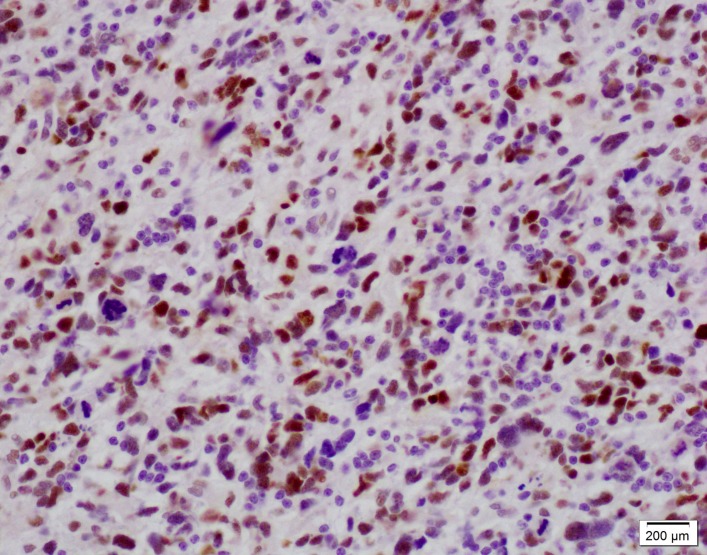

Immunohistochemical staining for p53 will be performed using avidin–biotin–peroxidase enzyme complex with a prediluted monoclonal anti-p53 antibody (Ventana). A positive p53 control (figure 2) standardised in the laboratory will be used in the assessment of the mucosal surgical margins. Positive p53 staining of the malignant cells will be indicated by an unequivocal brown stain of the nucleus.

Figure 2.

Positive control (glioblastoma with p53 mutation) for p53 antibody at 200× magnification showing unequivocal brown stain of the nucleus.

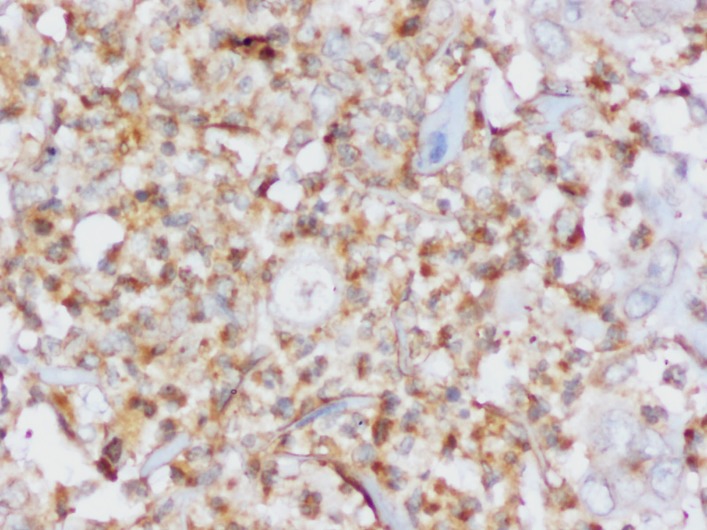

Immunohistochemical staining for eIF4E will be carried out with a polyclonal antibody to eIF4E at 1:500 dilution. Positive eIF4E control (figure 3) has been standardised on breast tissue with infiltrating duct carcinoma. A brown perinuclear staining of the tumour cells indicates a positive eIF4E stain.

Figure 3.

Positive control (carcinoma breast) for eIF4E antibody at 400× magnification showing unequivocal brown stain around the nucleus.

The tumour and margins will be graded and scored for both p53 and eIF4E according to the intensity and percentage of cells. Cases positive will also be evaluated using a 10× objective in at least 10 fields by light microscopy. Areas containing the most uniformly stained tissue will be chosen for evaluation. Immunoexpression will be quantified for (1) per cent of immunopositive neoplastic cells per 10 fields and (2) average intensity of immunostaining in the positive neoplastic cells per 10 fields. The per cent positive cells will be graded on scale of 1–4 (1=1%–25% positive; 2=26%–50% positive; 3=51%–75% positive and 4=76%–100% positive). Immunostaining intensity will be graded 1–3 (1=weak; 2=moderate and 3=strong).

Prior to embarking on interpretation, coauthors SJ and GC will come to a consensus on scoring and interpretation of the staining. Subsequently, each case will be read by SJ and supervised/counterchecked by GC. The two observers will be blinded to follow-up information.

Follow-up

All patients will be followed-up and reviewed clinically every 3 months for the first year and at 6-month interval in the second year. In case of any suspicion, a biopsy to rule out recurrence will be performed.

Evaluation of outcomes

The primary outcomes are to (1) list the patients whose surgical margins are reported free of tumour with routine H&E staining that show positive immunohistochemical staining with p53 and/or eIF4E, (2) list the patients with disease recurrence and metastasis and (3) evaluate the use of Lugol’s iodine and VELscope in the patients from Darwin.

The secondary outcomes are to correlate recurrence of disease to positivity with p53 and eIF4E and correlate metastasis to positivity with p53 and eIF4E.

During follow-up reviews, patients will be assessed by local examination, biopsy of a suspicious lesion and MRI scans.

The outcomes will be evaluated based on data collected from patient files with regards to period of tumour-free survival, time taken for recurrence and/or metastasis, disease specific survival and overall survival.

Data management

The data collection and entry on an excel spreadsheet based on the study proforma will be stored by SJ in a password protected computer and a portable external hard drive.

Statistical analysis

The data on the surgical margins will be analysed statistically with SPSS software. Contingency table and the Χ2 test will be used to evaluate the association of eIF4E and p53 in the surgical margins with race, sex, stage, lymph node status, histological grade, postoperative radiation and eIF4E and p53 expression in the tumour and margins. A univariate analysis of clinical factors will be performed using the Cox model to identify those variables significantly associated with prognosis. Multivariate analysis will be performed to test for simultaneous effect of two or more factors. Event-time distributions for recurrence will be estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log rank test to determine the individual and combined effect of eIF4E and p53 expression in the margins. Similar curves will be performed to determine the effect of nodal status with eIF4E and p53 levels in the margins as nodal status is a significant prognostic factor in HNSCCs.

The consistency of protocol at both the sites will be assessed and the study will be periodically reviewed.

Discussion

The PRISM-HNSCC study is a bilateral research project conducted in two countries that have a huge burden of the disease. Among the states and territories in Australia, Northern Territory has the highest incidence of HNSCC and the RDH is the largest public hospital that facilitates the treatment and management of the disease.14 The actual burden of head and neck cancer in India is much greater than that reflected in the existing literature; however, it is the the most common malignancy encountered in Indian males.15 According to WHO, lip and oral cancers is the third most common cancer in India with nearly 68% mortality in 2012.16

Head and neck cancer is considered to progress through a multistep process from normal histological features to hyperplasia, mild dysplasia, moderate dysplasia, severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma and metastasis.3 Malignant transformation in cells is microscopically invisible with H&E stain which may be identified more accurately with molecular markers, especially in head and neck cancer, where, as a result of field cancerisation, the entire mucosa has often undergone atypical changes.1 3 9

A retrospective study conducted in Darwin suggested the efficacy of IHC with eIF4E and p53 antibodies on surgical margins of HNSCC in assessing the completeness of surgery; however, the sample size was very small for a concrete conclusion.14 Hence, a larger sample and prospective study was warranted to validate the above finding.

The aim in this study was also to evaluate the use of vital staining and VELscope. These methods are currently being studied by McCaul et al17 and Poh et al,18 respectively. The uniqueness of this project is the ability to study the outcomes and evaluate the efficacy of all three methods put together.

Staining with Lugol’s iodine solution has been shown to be effective in intraoperatively delineating the extent and precise border of the cancerous and dysplastic epithelium of the mucosal surface. It is cheap and hence can be used as a cost-effective, easy and quick screening test particularly in resource poor countries in detecting premalignant mucosa of individuals who consume tobacco, alcohol and have other lifestyle risk factors.5 6

VELscope has up to 55% accuracy in enhancing the direct visualisation of dysplastic mucosa. When combined with Lugol’s iodine, there is a potential for increasing the accuracy of the screening method. However, there is a capital expenditure with purchasing the equipment that may eventually be cost-effective in avoiding recurrence.7

Molecular analysis by performing IHC on surgical margins with eIF4E and p53 has been suggested to predict recurrence in previous studies; however, the role of p53 is controversial. Besides being a prognostic marker, eIF4E can also be targeted for therapeutic intervention.8 13 19

The TP53 and retinoblastoma pathways are almost universally disrupted in HNSCCs, indicating the importance of these pathways in head and neck tumourigenesis. More than 50% of HNSCC harbour TP53 gene mutations and over 50% demonstrate chromosomal loss at 17 p the site where the TP53 gene resides.1

The eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factor eIF4E has been found to be elevated in carcinoma breast and HNSCC, but not in benign lesions or normal mucosa. Recurrence of HNSCC was found to be more common in patients with elevated eIF4E in surgical margins. No other marker has provided evidence for being effective in detecting malignant alteration in cells. Since recurrence in HNSCC usually occurs within the first 2 years, the prognostic value of eIF4E can be used in a relatively short follow-up time.9

Since both the institutions receive HNSCC patients representative of sample population, the results can be validated to impact. This collaborative trial between two countries has set a precedence to build and continue the partnership for future studies, education and guide protocols in diagnosis and treatment.

Ethics and dissemination

All patients (or their legally authorised representative) included in this study will sign a consent form that describes this study and provides sufficient information for patients to make an informed decision about their participation. The written consent from every patient, at both centres will be obtained on the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC)/IRB-approved consent form, before that patient’s biopsy specimen undergoes IHC. Any protocol amendments will be communicated to investigators, HREC/IRB, participants and Australian New Zealand clinical trials registry, as deemed necessary.

Clinical and histopathological information about study participants will be accessible only to the site investigators and kept confidential by them. Identifiable data collected from electronic and hardcopy patient files by SJ will be stored securely on a password protected computer and external hard drive. Deidentified data will be used for analysis and interpretation of the results.

Paraffin sections and slides will be stored in the departmental repository.

Results of the study will be submitted for publication and presented as a dissertation and at departmental meetings and conferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Arrigo De Benedetti from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Louisiana State University, Shreveport, Louisiana, for providing the eIF4E antibody.

Footnotes

Contributors: Writing committee: all authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the study or acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the version that was submitted. SJ: Data collection and management.

Funding: This research is funded by Charles Darwin University and Flinders University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee, Darwin and Institutional Review Board, Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: Mahiban Thomas, Cameron Scott, James Badlani (Royal Darwin Hospital, Australia), Rama Jayaraj, Sheela Joseph (Charles Darwin University, Austrailia), Rajinikanth Janakiraman, Geeta Chacko, Meera Thomas, Sramana Mukhopadhyay (Christian Medical College, Vellore, India).

Contributor Information

Thomas Mahiban:

Cameron Scott, James Badlani, Rama Jayaraj, Sheela Joseph, Rajinikanth Janakiraman, Geeta Chacko, Meera Thomas, and Sramana Mukhopadhya

References

- 1.Pai SI, Westra WH. Molecular pathology of head and neck cancer: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol 2009;4:49–70. 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SG, Shah JP. TNM staging of cancers of the head and neck: striving for uniformity among diversity. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:242–58. 10.3322/canjclin.55.4.242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddad R, Shin D. Medical progress: recent advances in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1143–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Looser KG, Shah JP, Strong EW. The significance of "positive" margins in surgically resected epidermoid carcinomas. Head Neck Surg 1978;1:107–11. 10.1002/hed.2890010203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurita H, Kamata T, Li X, et al. Effectiveness of vital staining with iodine solution in reducing local recurrence after resection of dysplastic or malignant oral mucosa. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;50:109–12. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugimachi K, Kitamura K, Baba K, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis of early carcinoma of the esophagus using Lugol’s solution. Gastrointest Endosc 1992;38:657–61. 10.1016/S0016-5107(92)70560-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farah CS, McIntosh L, Georgiou A, et al. Efficacy of tissue autofluorescence imaging (VELScope) in the visualization of oral mucosal lesions. Head Neck 2012;34:856–62. 10.1002/hed.21834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban RH, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 1995;332:429–35. 10.1056/NEJM199502163320704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nathan CO, Franklin S, Abreo FW, et al. Analysis of surgical margins with the molecular marker eIF4E: a prognostic factor in patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2909–14. 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer 1953;6:963–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batsakis JG. Surgical excision margins: a pathologist’s perspective. Adv Anat Pathol 1999;6:140–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braakhuis BJ, Bloemena E, Leemans CR, et al. Molecular analysis of surgical margins in head and neck cancer: more than a marginal issue. Oral Oncol 2010;46:485–91. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathan CO, Sanders K, Abreo FW, et al. Correlation of p53 and the proto-oncogene eIF4E in larynx cancers: prognostic implications. Cancer Res 2000;60:3599–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh J, Jayaraj R, Baxi S, et al. An Australian retrospective study to evaluate the prognostic role of p53 and eIF4E cancer markers in patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC): study protocol. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013;14:4717–21. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.8.4717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra A, Meherotra R. Head and neck cancer: global burden and regional trends in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:537–50. 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.2.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International agency for research on cancer, World health organisation. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx (accessed 29 Sep 2015).

- 17.McCaul JA, Cymerman JA, Hislop S, et al. LIHNCS - Lugol’s iodine in head and neck cancer surgery: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of Lugol’s iodine to assist excision of moderate dysplasia, severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ at mucosal resection margins of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:310 10.1186/1745-6215-14-310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poh CF, Durham JS, Brasher PM, et al. Canadian Optically-guided approach for Oral Lesions Surgical (COOLS) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2011;11:462 10.1186/1471-2407-11-462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathan CO, Amirghahri N, Rice C, et al. Molecular analysis of surgical margins in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Laryngoscope 2002;112:2129–40. 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.