Abstract

Objective

There are limited data on the patterns of early sexual behaviours among Australian teenage heterosexual boys. This study describes the nature and onset of early sexual experiences in this population through a cross-sectional survey.

Design

A cross-sectional survey between 2014 and 2015

Setting

Major sexual health clinics and community sources across Australia

Participants

Heterosexual men aged 17–19 years

Results

There were 191 men in the study with a median age of 19.1 years. Median age at first oral sex was 16.4 years (IQR: 15.5–17.7) and 16.9 years (IQR: 16.0–18.0) for first vaginal sex. Most men had engaged in oral sex (89.5%) and vaginal sex (91.6%) in the previous 12 months with 32.6% reporting condom use at last vaginal sex. Of the total lifetime female partners for vaginal sex reported by men as a group (n=1187): 54.3% (n=645) were the same age as the man, 28.3% (n=336) were a year or more younger and 17.4% (n=206) were a year or more older. Prior anal sex with females was reported by 22% with 47% reporting condom use at last anal sex. Median age at first anal sex was 18.2 years (IQR: 17.3–18.8). Anal sex with a female was associated with having five or more lifetime female sexual partners for oral and vaginal sex.

Conclusions

These data provide insights into the trajectory of sexual behaviours experienced by teenage heterosexual boys following sexual debut, findings which can inform programme promoting sexual health among teenage boys.

Keywords: Sexual behaviours, sexual trajectory, first sex, heterosexual, teenage, adolescent

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The findings of this study are from 191 young heterosexual men aged 17–19 years recruited in both clinic-based and community-based settings.

This is the first Australian study that provides data on the early sexual experiences of teenage heterosexual boys in Australia including the sequence and timing of first oral, vaginal and anal sex experiences with girls.

The majority of men were recruited from sexual health clinics which may have biased towards more sexually active men.

Introduction

Early sexual experiences among teenagers may have longer-term influences on individuals’ sexual lives and sexual health. Risk taking, which is part of the normal development process and experience among adolescents,1 may expose young people to sexually transmitted infections (STI) and unintended pregnancy. Some studies have linked early initiation of sexual activity among adolescents with higher rates of unintended pregnancy, experiences of sexual violence, higher numbers of sexual partners, STIs and engagement in anal sex.2–4 Australian surveillance reports have shown that the prevalence of chlamydia is high among adolescents aged 16–19 years (4.7% in men and 8.0% in girls).5 Young people are one of the key priority populations targeted in the third Australian National STI Strategy, and thus the factors associated with sexual behaviours and their concomitant outcomes are critical.

Most studies have used an arbitrary age cut-off to define early sexual intercourse, ranging from 13 years in the US Youth Risk Behaviour Survey6 to 16 years in Australian,2 and British surveys.7 It has been suggested that there is a temporal order for the first experience of different sexual activities among teenagers, for instance, that teenagers initiate oral sex first, followed by vaginal sex.8 9 However, there have been few published data to support this. To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the temporal order of and the average time interval between first oral, vaginal and anal sex among teenage heterosexual boys. Understanding the patterns of early sexual behaviours of teenage boys could inform public health messages and programme aimed at improving the sexual health of young people. The aim of this study was to provide data on the early sexual experiences of heterosexual men in Australia including the trajectory of first, specific sexual acts.

Methods

Study participants

Men were eligible for the study if they (1) were aged between 17 and 19 years, (2) reported no sexual contact with another man in the previous 12 months and (3) were residents in Australia from the age of 12 or younger. All men in this study were participants in the Impact of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Research Study (IMPRESS) which aimed to determine the change in prevalence of penile human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes among teenage boys following the introduction of male vaccination.10

Study design and setting

This study employed both clinic-based and community-based recruitment to establish a more representative sample. Clinic-based recruitment took place at sexual health, family planning and youth (Headspace) clinics in Victoria (Melbourne), New South Wales (Sydney), Western Australia (Perth), South Australia (Adelaide), Tasmania (side-wide service) and Queensland (Cairns). Community-based recruitment sources in Victoria included placement of promotional posters across universities and Technical and Further Education (TAFE) campuses, peer-led promotion at youth-oriented events such as music festivals and use of university student online message boards. Potential participants could register interest on the study website which serves as a screening tool for eligibility criteria. All potential participants would be contacted by the research nurse to confirm the eligibility via telephone. Participants could complete a self-administered paper-based questionnaire either attending the clinic or requesting a study pack sent to them. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The questionnaire contained questions about demographic characteristics (eg, age, education level) and sexual behaviours. Questions on sexual behaviours were stratified according to three sexual practices: oral (fellatio), vaginal and anal sex. Questions included the age of first sex (year and month), the time since last episode of sex, number of partners in their lifetime and in the previous 12 months and condom use at last episode of sex. In order to investigate sexual mixing patterns by age,11 12 men who reported vaginal sex were also asked how many female partners they had had vaginal sex with who were (1) the same age, (2) a year or more younger and (3) a year or more older. The questionnaire took approximately 10 min to complete. All participants received a AU$ 20 gift voucher for their participation.

Ethical approval was obtained from the six Human Research and Ethics Committees governing recruitment sites: the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (503/13), South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Ethics Human Research Ethics Committee (14/253), South Metropolitan Health Services Human Research Ethics Committee (14/76), Royal Adelaide Hospital Committee (HREC/14/RAH/441), Tasmania Health & Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (H0014507) and Far North Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/QCH/119–940).

Statistical analyses

Median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported for all continuous variables such as age and number of partners. Proportions were reported for all categorical variables such as condom use. Univariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the potential predictors for anal sex among teenage boys. Potential predictors included country of birth (Australia vs overseas), age (continuous), number of lifetime female sexual partners for oral and vaginal sex (<5 vs ≥5) and age at first oral and vaginal sex (<16 vs ≥16). The number of lifetime female sexual partners for oral and vaginal sex were categorised using the sample median as a cut-off, while age at first oral and vaginal sex were categorised based on the age of consent in Australia. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were not performed because only one variable was significant in univariate analyses. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed in order to present the cumulative probability by age of men having had first sex for oral, vaginal and anal sex. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata V.13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 191 men were recruited into the study (table 1). The median age of participants was 19.1 years (IQR: 18.4–19.6 years). Ninety-two (48.2%) men were enrolled in tertiary studies at the time of recruitment, and 170 (89.0%) were born in Australia. One hundred and forty-five (75.9%) men were recruited from clinics, and 46 (24.1%) were recruited from community-based sources. Eleven (5.8%) men reported no previous sexual contact (oral, vaginal or anal sex) with a female in their lifetime: three were aged 17, five were aged 18 and three were aged 19 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics and sexual behaviours reported by heterosexual teenage boys

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 19.1 (18.4–19.6) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Have not completed Year 12 | 23 (12.0%) |

| Completing year 12 | 27 (14.1%) |

| Completed year 12 | 49 (25.7%) |

| Current tertiary study | 92 (48.2%) |

| Country of birth, n (%) | |

| Australia | 170 (89.0%) |

| Other | 21 (11.0%) |

| Circumcised*, n (%) | |

| Yes | 28 (14.8%) |

| No | 161 (85.2%) |

| Sexual behaviours | |

| Age at first sexual behaviours with a woman, median (IQR) | |

| Oral sex† | 16.4 (15.5–17.7) |

| Vaginal sex | 16.9 (16.0–18.0) |

| Anal sex | 18.2 (17.3–18.8) |

| Number of partners in lifetime, median (IQR)‡ | |

| Oral sex† | 4 (2–8) |

| Vaginal sex | 4 (2–8) |

| Anal sex | 1 (1–2) |

| Engagement in sexual behaviours in lifetime, n (%) | |

| No sexual contact | 11 (5.8%) |

| Oral sex only† | 3 (1.6%) |

| Vaginal sex only | 4 (2.1%) |

| Oral and vaginal sex only† | 131 (68.6%) |

| Oral, vaginal and anal sex† | 42 (22.0%) |

| Engagement in sexual behaviours in the previous 12 months, n (%) | |

| No sexual contact | 13 (6.8%) |

| Oral sex only† | 3 (1.6%) |

| Vaginal sex only | 7 (3.7%) |

| Oral and vaginal sex only† | 131 (68.6%) |

| Oral, vaginal and anal sex† | 37 (19.4%) |

| Number of partners in the previous 12 months, median (IQR)‡ | |

| Oral sex† | 2 (1–4) |

| Vaginal sex | 2 (1–4) |

| Anal sex | 1 (1–1) |

| Condom use at last episode of vaginal sex, n (%)‡ | |

| Yes | 57 (32.6%) |

| No | 118 (67.4%) |

| Condom use at last episode of anal sex, n (%)‡ | |

| Yes | 18 (48.6%) |

| No | 19 (51.4%) |

*Two men did not report the circumcision status.

†Oral sex is defined as oral-penile sex (ie, fellatio).

‡Men who had not engaged in certain types of sexual activity were excluded.

Age and sequence at first sexual experiences

The median age at first oral sex was 16.4 years (IQR: 15.5–17.7), first vaginal sex was 16.9 years (IQR: 16.0–18.0) and first anal sex was 18.2 years (IQR: 17.3–18.8) (table 1). The majority of men followed a sequence of initial oral sex, followed by vaginal sex (n=63, 36.0%) (table 2), and the median time interval for those who followed this sequence was seven months. The next most common (n=49, 28.0%) was first oral and first vaginal sex occurring at the same time. Fewer men first experienced vaginal sex before first oral sex (n=19, 10.9%), and the median time interval who followed this sequence was 3.5 months. In addition, some men (n=19; 10.9%) first experienced oral and vaginal sex at the same time then followed by anal sex after a median of 1.6 years. A small proportion of men (n=13, 7.4%) followed a sequence of first oral sex, followed by first vaginal sex after a median of three months, then anal sex a median of one year after first vaginal sex.

Table 2.

Patterns of sexual trajectories among 175 teenage boys

| Patterns of sexual trajectories | N | Per cent |

| OS only | 3 | 1.7% |

| VS only | 4 | 2.3% |

| OS first, then VS | 63 | 36.0% |

| VS first, then OS | 19 | 10.9% |

| OS and VS at the same time | 49 | 28.0% |

| OS and VS at the same time, then AS | 19 | 10.9% |

| OS first, then VS, then AS | 13 | 7.4% |

| VS first, then OS, then AS | 3 | 1.7% |

| AS first, then OS and VS at the same time | 1 | 0.6% |

| OS first, then VS and AS at the same time | 1 | 0.6% |

Note. Of the 180 teenage boys who had ever had any sexual contact, only 175 men reported the age at first oral, vaginal and anal sex.

AS, anal sex; OS, oral sex; VS, vaginal sex.

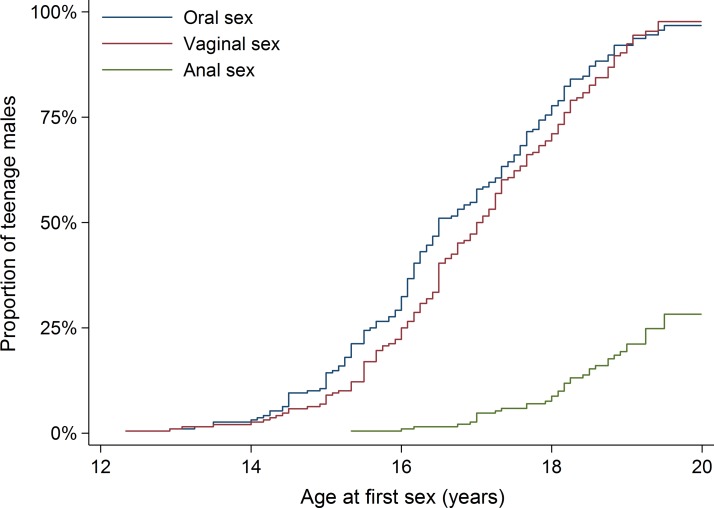

Figure 1 shows the cumulative probability of men in the study and age at first oral, first vaginal and first anal sex. For oral sex, 54.8% had ever engaged in oral sex by age 17. This increased to 75.5% by the age of 18, 92.1% by the age of 19 and 96.8% by the age of 20. For vaginal sex, 47.3% had ever engaged in vaginal sex by the age of 17. This increased to 69.4% by the age of 18, 90.4% by the age of 19 and 97.7% by the age of 20. For anal sex, 2.7% had ever engaged in anal sex by the age of 17. This increased to 7.6% by the age of 18, 19.4% by the age of 19 and 28.3% by the age of 20.

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of teenage heterosexual boys and age at first oral, first vaginal and first anal sex with females.

Sexual practices during the previous 12 months and over lifetime

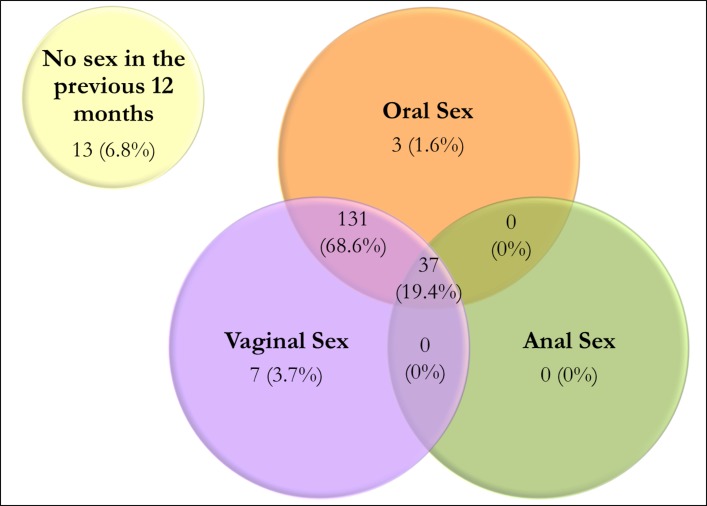

Of the 191 men, 180 (94.2%) had sexual contact with a woman over their lifetime: 131 (68.6%) had both oral and vaginal sex; 42 (22.0%) had oral, vaginal and anal sex; four (2.1%) had vaginal sex only; and three (1.6%) had oral sex only (table 1).

Of the 191 men, 178 (93.2%) reported having sex with a woman in the previous 12 months: 131 (68.6%) had both oral and vaginal sex; 37 (19.4%) had oral, vaginal and anal sex; seven (3.7%) had vaginal sex only; and three (1.6%) oral sex only (figure 2). None had anal sex only (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of oral, vaginal and anal sex practices in the previous 12 months among 191 teenage boys.

Among those who had engaged in oral sex, the median number of female partners for oral sex was four (IQR: 2–8) over their lifetime. Of the 171 (89.5%) men who had had oral sex in the previous 12 months, the median number of female partners for oral sex over the previous 12 months was two (IQR: 1–4) (table 1).

Among those who had ever engaged in vaginal sex, the median number of female partners for vaginal sex was the same as for oral sex: four (IQR: 2–8) over their lifetime. Of the 175 (91.6%) men who had vaginal sex in the previous 12 months, 57 (32.6%) used a condom at last episode of vaginal sex, and the median time since last vaginal sex was seven (IQR: 3–35) days (table 1).

Among those who had engaged in anal sex with women, the median number of female partners for anal sex was one (IQR: 1–2) over their lifetime. Of the 37 (19.4%) men who had anal sex in the previous 12 months, the median number of female anal sex partners was one (IQR: 1–1). Only 18 (48.6%) men used a condom at last episode of anal sex and the median time since the last episode of anal sex was 70 (IQR: 21–182) days (table 1). Men who had ever engaged in anal sex were significantly more likely to have had five or more lifetime female partners for oral and vaginal sex (OR: 2.03; 95% CI 1.01 to 4.10) compared with men who had less than five partners for oral and vaginal sex. Country of birth, age of men and age at first oral or vaginal sex were not significantly associated with anal sex.

Age of female partners

A total of 1187 female partners were reported by 169 men who had vaginal sex with a woman: 645 (54.3%) of the female partners were the same age as the man; 336 (28.3%) were a year or more younger than the man (median of one year younger); and 206 (17.4%) were a year or more older than the man (median of two years older).

Discussion

This is the first study that provides data on the early sexual experiences of teenage heterosexual boys in Australia including the sequence and timing of first oral, vaginal and anal sex experiences with women. We found most teenage boys, who had a median age of 19, followed a pattern of engaging in oral sex first followed by vaginal sex some months later, or initiating both sexual acts at the same time. This contrasts with the early sexual experiences reported by older Australians where first oral sex usually occurred six years after first vaginal sex.13 Around one in five men reported previously engaging in anal sex with women. This was more likely among those who had higher numbers of lifetime sex partners for oral and vaginal sex.

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. The majority of men were recruited from sexual health clinics in Australia which may have biased towards more sexually active men, hence the reported behaviours may not be representative of all teenage heterosexual boys in Australia. Our study showed that more than 90% of sexually active teenage boys have had oral and/or vaginal sex by the age of 19. The proportion of men ever having oral and vaginal sex in our study is higher than the national community-based surveys that have been conducted in Australia14 and the UK.7 The Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships survey reported that 65% of 16–19-year-old male participants had vaginal sex and 64% had oral sex.14 In addition, the nature of the relationships between men and their female sexual partners was not collected, that is, whether they were regular partners, girlfriends or casual sexual contacts. Sexual practices and condom use with regular or casual partners may be different and further studies are required. Lastly, self-reporting and recall bias may have occurred in this study which requires participants to recall their first sexual activity.

One in five men in our study had engaged in anal sex in the previous 12 months, which is similar to the proportion reported by female university students aged 17–21 years in Melbourne (20%).15 This is also similar to results reported in surveys from Singapore (23%, men aged 14–19 years)16 and the UK (19%, aged 16–24 years).7 Our finding that anal sex is associated with a higher number of partners for oral and vaginal sex has also been noted in a previous study in California.17 A UK study found that men who engage in anal sex mainly satisfy their sexual pleasure while women most frequently view it as painful.18 Some teenage women consider anal sex as a way of avoiding pregnancy.19 Generally, where anal sex is practised by young heterosexual men, it is as part of a greater sexual repertoire that includes vaginal and/or oral sex. This finding is consistent with a previous study in Baltimore.20 Some studies have shown that engagement in anal sex among teenagers is influenced by viewing pornography,21 22 in which condoms are also largely absent.23 Unprotected anal sex may increase the risk of HIV and rectal STI. Half the men in our study did not use a condom at their last episode of anal sex. Low condom use during anal sex by teenagers may be due to the fact that most consider condoms as a form of contraception rather than as protection against HIV and STI.24 In a study of girls aged 14–19 years attending a sexual health service in Los Angeles, the positivity of rectal chlamydia or gonorrhoea was 21%.25 As extra-genital STI screening for heterosexuals is not currently recommended in most STI screening guidelines, it is possible that females with rectal STIs are not being diagnosed or treated.

The median interval between first oral sex and first vaginal sex among men in our study is similar to that seen in a US study of teenage boys aged 16–19 years showing that oral and vaginal sex are mostly initiated simultaneously or within six months of each other, and oral sex usually occurs before vaginal sex.9 Many young people do not consider oral sex as ‘sex’.26 Non-coital sexual experiences such as oral sex may be a means to develop trust and comfort within a relationship, and demonstrate sexual skills before first vaginal sex.8 27 This appears to be the ‘normal’ sequence of the sexual trajectory.8

In Australia, school-based sex education is primarily delivered between year 7 (aged 12–13 years) and year 10 (aged 15–16 years). However, sex education information in Australia is mainly focused on biology and contraception,28 with less focus on STIs, relationships and sexuality. Furthermore, sexual practices other than penile–vaginal sex, such as oral and anal sex, may be considered taboo and hence are not covered in current sex education programme despite the frequency with which young people engage in these activities, and the risks they may pose.28 Non-school-based sex education, improved school-based programme and safer sex promotion using campaigns and social media-targeted young people are necessary.29

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Melbourne Sexual Health Centre clinic staff and staff at other clinics for their support including: Melissa Power, Jane Gilbert, Carol Pavitt, Emma Clements, El Thompson, Barb Lennox, Fiona Anderson, Collette Cashman, Michelle Andrews, and Clare Roberts.

Footnotes

Contributors: The IMPRESS Study investigators include Marcus Chen, Christopher Fairley, Catriona Bradshaw, John Kaldor, Sepehr Tabrizi, Suzanne Garland, Jane Hocking, David Regan, Julia Brotherton, Anna McNulty, Darren Russell, Lewis Marshall and Louise Owen. Eric Chow and Rebecca Wigan performed the data analyses. Eric Chow, Rebecca Wigan and Marcus Chen wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors helped to interpret results and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The IMPRESS Study is funded by a Merck Investigator Initiated Studies Program, Protocol 50939. Eric Chow is supported by the Early Career Fellowships from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (number 1091226).

Competing interests: EPFC has received educational grants from Seqirus and bioCSL to assist with education, training and academic purposes in the area of HPV. CKF has received honoraria from CSL Biotherapies and Merck, and research funding from CSL Biotherapies. CKF owns shares in CSL Biotherapies, which is the manufacturer of Gardasil. MYC has been the principal investigator on Merck Investigator Initiated Studies and received funding to conduct HPV studies under these programmes. CKF, CSB, DGR, JB, AM, DR, LM and LO are co-investigators on Merck Investigator Initiated Studies. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the six Human Research and Ethics Committees governing recruitment sites: the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (503/13), South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Ethics Human Research Ethics Committee (14/253), South Metropolitan Health Services Human Research Ethics Committee (14/76), Royal Adelaide Hospital Committee (HREC/14/RAH/441), Tasmania Health & Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (H0014507) and Far North Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/QCH/119-940).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Igra V, Irwin CE. Theories of Adolescent Risk-Taking Behavior : DiClemente RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE, Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior. Boston, MA: Springer US, 1996:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rissel C, Heywood W, de Visser RO, et al. First vaginal intercourse and oral sex among a representative sample of Australian adults: the Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sex Health 2014;11:406–15. 10.1071/SH14113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, et al. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:774–80. 10.1093/aje/kwi095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgartner JN, Waszak Geary C, Tucker H, et al. The influence of early sexual debut and sexual violence on adolescent pregnancy: a matched case-control study in Jamaica. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2009;35:021–8. 10.1363/3502109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeung AH, Temple-Smith M, Fairley CK, et al. Chlamydia prevalence in young attenders of rural and regional primary care services in Australia: a cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust 2014;200:170–5. 10.5694/mja13.10729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sneed CD. Sexual risk behavior among early initiators of sexual intercourse. AIDS Care 2009;21:1395–400. 10.1080/09540120902893241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercer CH, Tanton C, Prah P, et al. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013;382:1781–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis R, Marston C, Wellings K. Bases, Stages and ‘Working your Way Up’: Young People’s Talk about Non-Coital Practices and ‘Normal’ Sexual Trajectories. Sociol Res Online 2013;18:1–9. 10.5153/sro.2842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song AV, Halpern-Felsher BL. Predictive relationship between adolescent oral and vaginal sex: results from a prospective, longitudinal study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:243–9. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machalek DA, Chow EP, Garland SM, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence in unvaccinated heterosexual males following a national female vaccination program. J Infect Dis 2016;215:202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow EPF, Fairley CK. Association between sexual mixing and genital warts in heterosexual men in Australia: the herd protection from the female human papillomavirus vaccination program. Sex Health 2016;13:489–90. 10.1071/SH16053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow EPF, Read TRH, Law MG, et al. Assortative sexual mixing patterns in male-female and male-male partnerships in Melbourne, Australia: implications for HIV and sexually transmissible infection transmission. Sex Health 2016;13:451–6. 10.1071/SH16055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rissel CE, Richters J, Grulich AE, et al. Sex in Australia: first experiences of vaginal intercourse and oral sex among a representative sample of adults. Aust N Z J Public Health 2003;27:131–7. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00800.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rissel C, Badcock PB, Smith AM, et al. Heterosexual experience and recent heterosexual encounters among Australian adults: the Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sex Health 2014;11:416–26. 10.1071/SH14105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Morton A, et al. Early sexual experiences and risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 2009;200:1662–70. 10.1086/648092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng JY, Wong ML, Chan RK, et al. Gender Differences in Factors Associated With Anal Intercourse Among Heterosexual Adolescents in Singapore. AIDS Educ Prev 2015;27:373–85. 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.4.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erickson PI, Bastani R, Maxwell AE, et al. Prevalence of anal sex among heterosexuals in California and its relationship to other AIDS risk behaviors. AIDS Educ Prev 1995;7:477–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marston C, Lewis R. Anal heterosex among young people and implications for health promotion: a qualitative study in the UK. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004996 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halperin DT. Heterosexual anal intercourse: prevalence, cultural factors, and HIV infection and other health risks, Part I. AIDS Patient Care STDS 1999;13:717–30. 10.1089/apc.1999.13.717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ompad DC, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD, et al. Predictors of early initiation of vaginal and oral sex among urban young adults in Baltimore, Maryland. Arch Sex Behav 2006;35:53–65. 10.1007/s10508-006-8994-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harkness EL, Mullan B, Mullan BM, Blaszczynski A, et al. Association between pornography use and sexual risk behaviors in adult consumers: a systematic review. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2015;18:59–71. 10.1089/cyber.2014.0343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim MS, Carrotte ER, Hellard ME. The impact of pornography on gender-based violence, sexual health and well-being: what do we know? J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:3–5. 10.1136/jech-2015-205453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grudzen CR, Elliott MN, Kerndt PR, et al. Condom use and high-risk sexual acts in adult films: a comparison of heterosexual and homosexual films. Am J Public Health 2009;99:S152–S156. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lust FM. trust and latex: Why young heterosexual men do not use condoms. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2003;5:353–69. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javanbakht M, Gorbach P, Stirland A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of rectal Chlamydia and gonorrhea among female clients at sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:917–22. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31826ae9a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. Would you say you "had sex" if ? JAMA 1999;281:275–7. 10.1001/jama.281.3.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis R, Marston C, Sex O. Oral Sex, Young People, and Gendered Narratives of Reciprocity. J Sex Res 2016;53:776–87. 10.1080/00224499.2015.1117564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell A, Patrick K, Heywood W, et al. 5th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2013. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yonker LM, Zan S, Scirica CV, et al. "Friending" teens: systematic review of social media in adolescent and young adult health care. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e4 10.2196/jmir.3692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.