Abstract

Necrotising fasciitis (NF) is a destructive bacterial infection and has often been described in media reports as a ‘flesh-eating disease’, which if diagnosed late is associated with worse outcome. Unfortunately, diagnosing NF is difficult due to the similar presentation of NF compared with other types of skin and soft tissue infections. The early presentation of NF only shows tenderness, swelling, erythema and warm skin. Moreover, NF is normally accompanied with aberrant laboratory findings, mainly elevated C reactive protein (CRP) levels. In this case report we evaluate the diagnostic process of a patient with NF without aberrant infection parameters; both normal levels of CRP and white blood cell count were seen.

Keywords: general surgery, adult intensive care, infectious diseases, infections

Background

Necrotising fasciitis (NF) is a destructive bacterial infection characterised by necrosis of the fascia and subcutaneous tissue, accompanied by severe systemic toxicity. It is a rapidly progressing skin infection which, if diagnosed late, leads to worse outcome. There are four types of NF.1 Type I is polymicrobial with at least one anaerobic species with one or more facultative anaerobic streptococci and members of the enterobacteriaceae. Type II NF is a monobacterial infection caused by haemolytic streptococcus group A. Type III NF is caused by the marine Vibrio species. The infection spreads through a wound caused by marine insects. Type IV NF is caused by fungal cases of Candida. This last named type NF is very rare.

The incidence of NF is low, only 0.4 cases per 100 000 people.2 However, NF has a high mortality rate, ranging from 6% to 73%.3–8 This mortality rate has been found to decrease with early diagnosis followed by broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical debridement.6 9–11 Predisposing factors for this disease include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, cirrhosis malignancy and immunodeficiency.1 4 6 12

The most common symptoms of NF are oedema (80.1%), pain (79.0%), erythema (73.0%), bullae (25.6%), cutaneous necrosis (24.1%) and subcutaneous emphysema (20.3%).4 6 These symptoms should direct the diagnostic process towards NF. However, NF is difficult to diagnose as early symptoms such as tenderness, oedema and erythema can be seen in several other skin and soft tissue infections, such as cellulitis.10 13

Case presentation

We present a case of a 69-year-old man with a medical history of periodically treated pneumonias, Billroth II gastrojejunostomy reconstruction of his stomach, ischaemic heart disease and pure red cell aplasia temporarily treated with prednisone in 1981 and treated with blood transfusions in 2007.

On Thursday, 8 October of 2015, he was referred to our emergency department at 14:54 with a 2-day history of malaise, fever, progressive pain, erythema and oedema of both his legs without trauma. The level of pain prohibited the patient to walk. Azithromycin was prescribed by the general practitioner, since 1 day.

On presentation a moderately ill man with cyanotic lips and fingers of both hands was seen. The patient’s temperature was 38.9°C, blood pressure 135/88 mm Hg, pulse 122/min, respiratory rate 25/min and oxygen saturation 98%. Visual inspection of both legs revealed an erythematous swollen right leg with ecchymosis, as well as a blister on his right foot without wounds. Multiple erythematous regions, without sharp margins, extended from the right leg to his lower abdomen, both groins and left thigh. Active and passive ranges of motion were limited due to pain. Diffuse tenderness at his right leg and left thigh was present. At palpation his right toes were cold. However, sensibility of both legs was undisturbed. An internist, followed by a dermatologist and later a surgeon examined the patient.

Investigations

First laboratory tests at 14:56 (reference values are shown in table 1) showed normal C reactive protein (CRP) (11 mg/L), normal white blood cell count (WBC) (6.3×109/L), normal haemoglobin levels (17.89 g/dL) and a thrombocytopaenia (53×109/L). Other laboratory tests showed a decrease in fibrinogen level (1.03 g/L), a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (41.2 s) and normal prothrombin time (PT, 11.4 s). Also, an elevated D-dimer (7369 ng/mL), an elevated creatine kinase (CK, 723 U/L), low serum sodium levels (134 mmol/L), high creatinine levels (192 µmol/L) and a normal postprandial plasma glucose level (8.6 mmol/L) were seen. At this time no arterial blood gas sample was taken. Despite the patient’s temperature of 38.9°C, no blood cultures were ordered immediately after presentation. An ECG and an ultrasonography of both legs were performed. The ECG only showed sinus tachycardia. Ultrasonography at 16:27 pm revealed subcutaneous oedema, especially in the right leg, without signs of a deep venous thrombosis. Doppler ultrasonography revealed normal peripheral flow in the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial artery.

Table 1.

Reference values of the laboratory findings

| Compound | Reference values |

| C reactive protein | 0–10 mg/L |

| White blood cell count | 4.0–10.0×109/L |

| Thrombocytes | 150−400×109/L |

| Haemoglobin concentration | 12.0–18.0 g/dL |

| Prothrombin time | 10.0–13.5 s |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | 24.0–37.0 s |

| Fibrinogen | 2.00–4.50 g/L |

| D-dimer | 0–500 ng/mL |

| Creatine kinase | 52–336 U/L |

| Serum sodium | 135–145 mmol/L |

| Blood creatinine | 80–115 µmol/L |

| Postprandial plasma glucose | <140 mg/dL |

| pH | 7.35–7.45 |

| Serum lactate | 0.5–2.5 mmol/L |

Differential diagnosis

Initial differential diagnosis consisted of sepsis, bullous erysipelas, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and NF. Due to the multifocal character and moderate signs of clinical illness, the working diagnosis was DIC. Initially there was no suspicion of a skin infection such as NF because of normal WBC and CRP levels.

Treatment

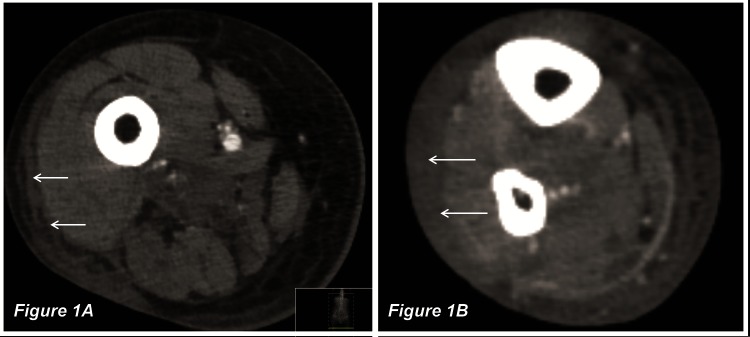

At 19:06 the blister was drained; this revealed an anaerobe smell with haemorrhagic fluid. The exudate was sent for culture along with blood cultures. At 19:27 the patient was hospitalised in the intensive care unit (ICU) because of sepsis. At the same time azitromycin was replaced by intravenous ciprofloxacin and intravenous clindamycin. Tobramycin was given once. On the ICU, the patient developed progressive hypotension and oliguria despite adequate fluid resuscitation and norepinephrine. A CT scan of the abdomen and legs was performed, and extensive subcutaneous oedema with involvement of the muscles of the right leg was seen (figure 1). In accordance with the clinical presentation, subcutaneous emphysema was not reported. Additional laboratory tests at 20:30 showed a metabolic acidosis with a low pH (7.33), high serum lactate (6.3 mmol/L), increased CK (1749 U/L) and increased PT levels (14.9 s). CRP was slightly elevated to 13 mg/L and WBC was low (2.3×109/L). The erythematous lesions increased with progressive blistering of the right leg and foot with a dusky blue skin of both legs (figure 2). At 23:56 Gram-stain of the exudate showed a Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium (a possible Escherichia coli).

Figure 1.

A CT of the legs shows extensive subcutaneous oedema with involvement of the muscles of the right upper leg (A) and lower leg (B). Emphysema was not reported.

Figure 2.

Visual inspection of both legs revealed swollen legs with multiple erythematous regions without sharp margins, blistering (*) and ecchymosis (arrows).

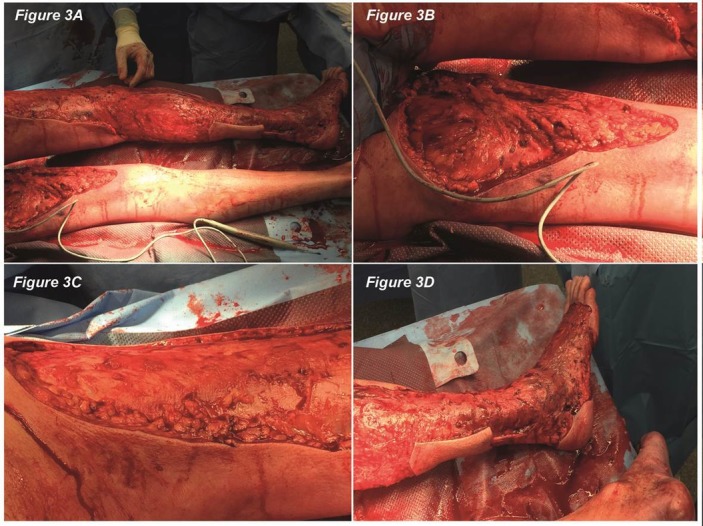

The patient continued to deteriorate and went into a critical and haemodynamically unstable condition. To rule out NF it was decided to perform an exploration of the lesions on both legs in the theatre. This procedure started on Friday at 00:07. During the surgical procedure, a typical aspect of NF was seen; after incising the skin and exposing the fascia, a necrotic greyish fascia was revealed at all lesions with small thrombosed vessels. An aggressive surgical debridement of the necrotic tissue was performed. This resulted in complete removal of the affected tissue of the entire right lower leg and foot, the lateral side of the right upper leg and left medial thigh. All the underlying muscles were vital (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The exploration in theatre (A) resulted in complete removal of the affected tissue of the left medial thigh (B), the lateral side of the right upper leg (C) and the entire right lower leg and foot (D). The underlying muscles were all vital.

Outcome and follow-up

After surgery the patient returned to the ICU. Despite the aggressive surgery, intravenous ciprofloxacin, intravenous clindamycin, tobramycin and inotropes, the clinical situation deteriorated. An acute respiratory distress syndrome developed with high ventilator settings. High doses of norepinephrine and milrinone were given. Laboratory tests showed a progressive metabolic acidosis (pH 6.96), with persistent high serum lactate (7.0 mmol/L), long PT (20.7 s) and high CK levels (1307 U/L). WBC and CRP returned to normal values (10.7×109/L and 10 mg/L). Despite all efforts, the patient developed multiple organ failure and died on Friday at 09:30, 18 hours after admission to our hospital. Definitive results from the microbiology department revealed an E. coli in both the exudate and blood culture.

Discussion

NF is a destructive bacterial infection and has often been described in media reports as a ‘flesh-eating disease’, classically linked to Streptococcus pyogenes, a group A streptococcus (type II).5 Our patient was already 1 days treated with antibiotics before presentation in our emergency room. This can cause a selection in culture results. We isolated an E. coli as a monoculture from the blood, and classified our case as a type I NF. There are numerous cases in which this culture was found.1 The patient in our case had none of the predisposing conditions like diabetes, chronic renal failure and malignancy, and was not immunocompromised at the onset of his disease.

Diagnosing NF is difficult due to the similar presentation of NF compared with other types of skin and soft tissue infections. The early presentation of NF only shows tenderness, swelling, erythema and warm skin. This may lead to confusion and delay of surgical debridement.6 9 12 Many diagnostic tools were developed for prompt diagnosis.3 12–14

First, the (warning) symptoms for NF include oedema, pain out of proportion, erythema, blisters, cutaneous necrosis and subcutaneous emphysema.4 6 15 In our case, the patient exhibits five of these (warning) symptoms. Only subcutaneous emphysema was not seen. In contrast to patients with erysipelas, patients with NF documented much more pain. Sixty-two per cent of patients with NF documented strong pain, whereas this symptom was not documented in patients with erysipelas.12 In our case, the level of pain prohibited the patient to walk. Combining the amount of pain together with the other warning symptoms, we believe in retrospect the clinical presentation was suggestive of NF.

To strengthen a suspicion of NF, Wong and Wang16 described the ‘Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis’ (LRINEC) score, which is based on laboratory findings. Therefore he scores the most reliable indicators of underlying NF, namely CRP, creatinine, haemoglobin, WBC, sodium and serum glucose. The LRINEC score stratifies patients into three groups: low risk of NF (score ≤5), medium risk of NF (score 6–7) and high risk of NF (score ≥8) (table 2).

Table 2.

Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis score

| C reactive protein | >150 mg/L | 4 points |

| White blood cell count | <15×109/L | 0 point |

| 15−25×109/L | 1 point | |

| >25×109/L | 2 points | |

| Haemoglobin | >13.5 g/dL | 0 point |

| 11–13.5 g/dL | 1 point | |

| <11 g/dL | 2 points | |

| Sodium | <135 mmol/L | 2 points |

| Blood creatinine | >141 µmol/L | 2 points |

| Postprandial plasma glucose | >10 mmol/L | 1 point |

According to the clinical practical guidelines for NF, an LRINEC score of ≥6 mandates wound exploration and surgical debridement.16 In our case the LRINEC score would have been 4 due to the levels of sodium (2 points) and creatinine (2 points). This score fits a low risk of NF. Therefore initially no surgical debridement should have been performed.

In literature, the LRINEC score has shown a doubtful performance.14 16 17 Holland showed a positive predictive value of only 57% and a negative predictive value of 86%. He stated that the LRINEC score only have a small effect on the post-test probability.17 Probably, the reason for the poor positive predictive value is the lack of specificity of the laboratory findings used in the LRINEC score.14 For instance, CRP levels rise in response to any form of inflammation.

However, recent literature showed otherwise. Borschitz et al12 found a significantly higher LRINEC score in patients with NF compared with patients with erysipelas, confirming the clinical relevance of this score. In his study, CRP levels turned out to be the most important laboratory parameter of this score. Patients with NF exhibited fivefold higher CRP levels compared with healthy controls. Moreover, this is the only parameter that yields 4 points.

Surprisingly, in our case of NF, the CRP level remains normal. This is very unusual. To our knowledge, in the literature there were no other case reports that describe cases of NF without elevated CRP levels. As a result, the LRINEC score was low.

The clinical warning symptoms and the LRINEC score are useful in diagnosing necrotising soft tissue infections. The same applies to imaging scans. However, the golden standard for detecting NF when there is any suspicion is wound exploration and surgical debridement. Performing imaging scans and determining the LRINEC score may never be a reason for delayed surgical debridement. Surgical debridement within 24 hours is associated with a lower mortality rate than surgical debridement after 24 hours.6 9–11 There is no significant difference between several periods of time within these 24 hours.7 Recent literature shows high numbers of delay of surgical treatment up to 40%.1 6 7 11 In our case, time to surgical debridement was 9 hours and 13 min, which was short with respect to the above-mentioned literature.

In conclusion, the presented case with fatal outcome is very exceptional due to the normal levels of CRP and WBC. As a result the risk of NF according to the LRINEC score was low. However, we believe the clinical presentation should have directed the diagnostic process towards NF earlier. Therefore, we should not have trusted the infection parameters only.

Patient’s perspective.

Patient’s wife:

“From my perspective, it all started the night before hospitalisation. My husband had progressive pain of the right leg. I phoned the General Practitioner (G.P.) on duty and he came to our house. After physical examination the GP thought of erysipelas. He gave medication [Azitromycin – Ed.] and left. Unfortunately, the medication did not help. My husband was in a lot of pain that night. I had never seen him crying before because of pain. The next morning, we phoned our own G.P. and I was sent to the pharmacy to get other medication [painkillers – Ed.]. However, when I came back I was shocked to see a large blister on his right feet. This blister was not there a few minutes earlier. Soon thereafter, a second blister came up. The G.P. came to our house and phoned immediately an ambulance. In the emergency department of the hospital, several doctors told my husband and us, he was very ill. Several investigations were done and after a while he was transported to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). We were brought to the relatives’ room to rest and wait. Later that night, the surgeon and intensivist called us to discuss the situation of my husband. They asked permission of my husband and our family to perform an exploration of both legs in theatre. My husband asked them what would happen if they did not perform an operation? The surgeon told him that he would probably die. We were told that an exploration in theatre was the best option at that moment. My husband accepted this. The operation took a long time. Nevertheless, his clinical situation worsened after the operation. We had a terrible night. Although the nurses and doctors did everything to save his life, he deceased early in the morning. I hope I have told you enough.”

Learning points.

Necrotising fasciitis (NF) could present similarly to other types of skin and soft tissue infections.

The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis score could be used for detecting NF, but a low risk score cannot exclude NF.

A patient with NF needs wound exploration and surgical debridement as soon as possible.

Normal infection parameters such as C reactive protein and white blood cell count do not exclude NF.

Footnotes

Contributors: CHLvS: writing article. SvS: revision and writing. LB: revision and writing. MB: revision and surgeon who treated the patient.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.van Stigt SF, de Vries J, Bijker JB, et al. Review of 58 patients with necrotizing fasciitis in the Netherlands. World J Emerg Surg 2016;11 10.1186/s13017-016-0080-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis Simonsen SM, van Orman ER, Hatch BE, et al. Cellulitis incidence in a defined population. Epidemiol Infect 2006;134:293–9. 10.1017/S095026880500484X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endorf FW, Cancio LC, Klein MB. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections: clinical guidelines. J Burn Care Res 2009;30:769–75. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181b48321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angoules AG, Kontakis G, Drakoulakis E, et al. Necrotising fasciitis of upper and lower limb: a systematic review. Injury 2007;38:S18–S25. 10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, et al. The epidemiology of invasive group a streptococcal infection and potential vaccine implications: United States, 2000-2004. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:853–62. 10.1086/521264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goh T, Goh LG, Ang CH, et al. Early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Br J Surg 2014;101:e119–e125. 10.1002/bjs.9371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang KF, Hung MH, Lin YS, et al. Independent predictors of mortality for necrotizing fasciitis: a retrospective analysis in a single institution. J Trauma 2011;71:467–73. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318220d7fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.May AK, Stafford RE, Bulger EM, et al. Treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect 2009;10:467–99. 10.1089/sur.2009.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung JP, Fung B, Tang WM, et al. A review of necrotising fasciitis in the extremities. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuster L, Nuñez DE. Using clinical pathways to aid in the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections synthesis of evidence. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2012;9:88–99. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nisbet M, Ansell G, Lang S, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: review of 82 cases in South Auckland. Intern Med J 2011;41:543–8. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borschitz T, Schlicht S, Siegel E, et al. Improvement of a clinical score for mecrotizing fasciitis: ’pain out of proportion' and high CRP levels aid the diagnosis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132775 10.1371/journal.pone.0132775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narasimhan V, Ooi G, Weidlich S, et al. Laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis score for early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in darwin. ANZ J Surg 2017. 10.1111/ans.13895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan MS. Diagnosis and management of necrotising fasciitis: a multiparametric approach. J Hosp Infect 2010;75:249–57. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e10–e52. 10.1093/cid/ciu296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong CH, Wang YS. The diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2005;18:101–6. 10.1097/01.qco.0000160896.74492.ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland MJ. Application of the Laboratory Risk Indicator in Necrotising Fasciitis (LRINEC) score to patients in a tropical tertiary referral centre. Anaesth Intensive Care 2009;37:588–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]