Abstract

Significance: In contrast to structural elements of the extracellular matrix, matricellular proteins appear transiently during development and injury responses, but their sustained expression can contribute to chronic disease. Through interactions with other matrix components and specific cell surface receptors, matricellular proteins regulate multiple signaling pathways, including those mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and H2S. Dysregulation of matricellular proteins contributes to the pathogenesis of vascular diseases and cancer. Defining the molecular mechanisms and receptors involved is revealing new therapeutic opportunities.

Recent Advances: Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) regulates NO, H2S, and superoxide production and signaling in several cell types. The TSP1 receptor CD47 plays a central role in inhibition of NO signaling, but other TSP1 receptors also modulate redox signaling. The matricellular protein CCN1 engages some of the same receptors to regulate redox signaling, and ADAMTS1 regulates NO signaling in Marfan syndrome. In addition to mediating matricellular protein signaling, redox signaling is emerging as an important pathway that controls the expression of several matricellular proteins.

Critical Issues: Redox signaling remains unexplored for many matricellular proteins. Their interactions with multiple cellular receptors remains an obstacle to defining signaling mechanisms, but improved transgenic models could overcome this barrier.

Future Directions: Therapeutics targeting the TSP1 receptor CD47 may have beneficial effects for treating cardiovascular disease and cancer and have recently entered clinical trials. Biomarkers are needed to assess their effects on redox signaling in patients and to evaluate how these contribute to their therapeutic efficacy and potential side effects. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 27, 874–911.

Keywords: : thrombospondin-1, CD47, matricellular proteins, nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, hydrogen sulfide

Table of Contents

B. Historical evidence linking matricellular proteins and redox signaling

C. Thrombospondin-1 regulation of soluble guanylate cyclase and downstream targets

D. Physiological functions of TSP1/CD47 regulation of NO signaling

3. Regulation of other matricellular protein expression by NO

IV. Thrombospondin-1 Regulation of H2S Biosynthesis and Signaling

VIII. CD47 Regulation of Redox Homeostasis in Irradiated Cells

B. CD47-dependent regulation of redox metabolites in irradiated cells

IX. TSP1/CD47 Regulation of Stem Cell and Tissue Self-Renewal

B. TSP1 and CD47 in stem cell self-renewal and tissue regeneration

A. Dysregulation of NO signaling by TSP1/CD47 in clinical disease

1. Association of elevated TSP1 with impaired NO signaling in cardiovascular disease

I. Introduction

A. What are matricellular proteins?

Matricellular proteins are a functional family of secreted proteins that was first described by Paul Bornstein in 1995 (16). Matricellular proteins are not constitutive structural elements of extracellular matrix, rather they function as regulatory molecules that are present in extracellular matrix at specific times during development, tissue remodeling, and responses to injury or chronic disease states. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) is a prototypical member of this family, which has grown to include four additional thrombospondins (TSPs), tenascins, periostin, the secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) family, the five small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoprotein (SIBLING) family members, the CCN (CYR61, CTGF [connective tissue growth factor], and NOV [nephroblastoma overexpressed gene]) family, and other thrombospondin-repeat (TSR)-containing proteins such as the a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) family (142, 169, 209) (Fig. 1). Most matricellular proteins are multidomain proteins, whereas osteopontin, the prototypical member of the SIBLING family, is a small intrinsically disordered protein (252).

FIG. 1.

Matricellular protein families. The thrombospondin family in vertebrates consists of five members. TSP1 and TSP2 are trimeric proteins linked through disulfides in the coiled-coil region that follows the N-terminal HBDs. TSP1 and TSP2 contain three TSRs, which are absent in TSP3, TSP4, and COMP. The latter constitute a second subfamily of homopentamers linked through their coiled-coil regions. A HBD is absent in COMP. The SPARC family consists of SPARC, SPARC-like 1/Hevin, two SPARC-related modular calcium binding proteins (SMOC1 and SMOC2), follistatin-like 1, and three PARC/osteonectin, cwcv, and kazal-like domains proteoglycan proteins (SPOCK1–3). The follistatin and acidic domains are conserved among the family members, but the EF-hand of SPARC is not conserved. The CCN family consists of six members: CCN1, CYR61 (cysteine-rich angiogenic protein 61); CCN2, CTGF; CCN3, NOV; CCN4, WISP1 (WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein-1); CCN5, WISP2 (WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein-2); and CCN6, WISP3 (WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein-3). Tenascins are a family of hexameric proteins consisting of tenascin-C, tenascin-R, tenascin-X, and tenascin-W. The number of EGF-like repeats and fibronectin type 3 repeats are variable. The ADAMTS family contains 19 members with variable number of TSRs. ADAMTS, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs; CCN, CYR61, CTGF (connective tissue growth factor), and NOV (nephroblastoma overexpressed gene); COMP, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein; EF-hand, helix-loop-helix calcium-binding domain; EGF, epidermal growth factor; HBDs, heparin-binding domains; SPARC, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine; TSR, type 1 thrombospondin repeat. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

The first members of the TSP and SPARC families emerged in early metazoa and underwent gene duplications that diverged into their current family members (169). Gene deletion studies indicate relatively little overlap in functions of the five TSPs (3, 196), although some receptor interactions are conserved between family members. Integrins are the only known receptor class interacting with the primordial TSP in insects that remains functional for the modern proteins (26). Modern trimeric forms of TSP1 and TSP2 trace back at least to fish. TSP1 and TSP2 share >80% homology between their C-terminal domains, which mediates TSP1 binding to CD47, and homology decreases to 25% between their N-terminal domains. The TSP1 receptor CD47 originated in early land-dwelling vertebrates, roughly coincident with the appearance of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS/NOS3) (63).

In common with classical extracellular matrix proteins, most matricellular proteins contain several functional domains that mediate interactions with other extracellular matrix components and with specific receptors. This capacity for multifarious interactions has contributed to confusion in the literature because a given matricellular protein can elicit opposing responses in cells that express different subsets of its receptors, and responses of a given cell type can change over time as the expression of receptors and composition of the surrounding extracellular matrix microenvironment respond to external stimuli.

With a few exceptions, matricellular protein genes are generally not essential for life. Phenotypes of null mutants may only become evident when mice are subjected to a specific stress that induces matricellular protein expression or signaling. Despite these challenges, studies of matricellular protein function in transgenic mouse models and identification of genetic diseases linked to structural and regulatory mutations in specific matricellular protein genes have proven that they play important roles in physiology and pathophysiology (126, 142, 171, 243).

B. Historical evidence linking matricellular proteins and redox signaling

Earlier studies of TSP1 provided clues that altered redox signaling could mediate some cellular responses controlled by this protein. Immobilized TSP1 inhibited the ability of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) to induce an oxidative burst response in polymorphonuclear cells (PMN) (179). Conversely, TSP1 enhanced superoxide production by neutrophils stimulated with the chemoattractant formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP), and fMLP upregulated the binding of TSP1 to presumed receptors on these cells (257).

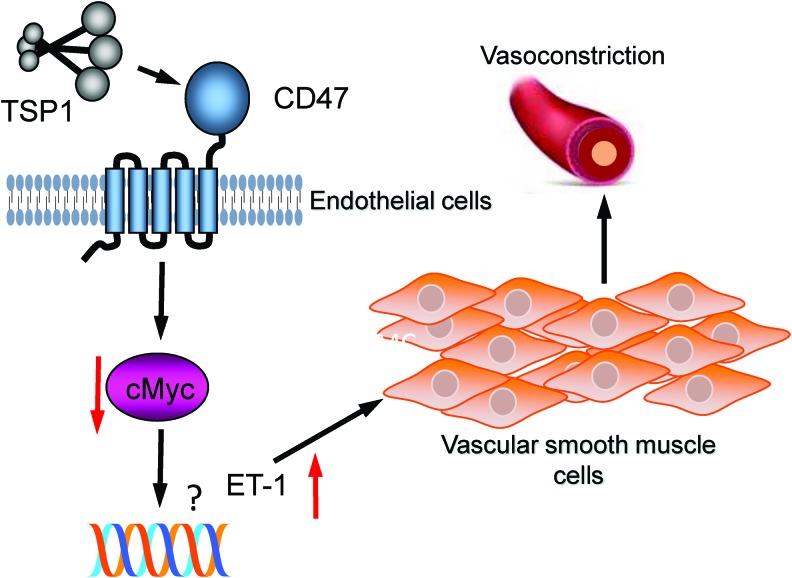

In retrospect, several earlier studies suggested an association between TSP1 and nitric oxide signaling. The ability of TSP1 to disrupt focal adhesions in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) required the activity of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (170), and treatment with TSP1 acutely decreased cGMP levels in a human melanoma cell line (68). A specific role of TSP1 in regulating NO-induced synthesis of cGMP was first identified in endothelial cells (93), and subsequent studies have revealed a broad role for TSP1 signaling through its receptor CD47 to adversely regulate cytoprotective cellular redox signaling (243).

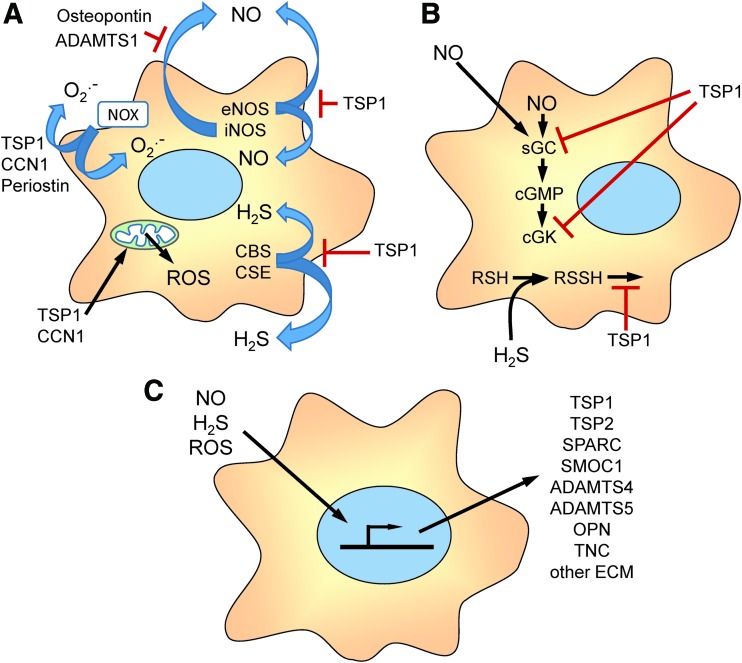

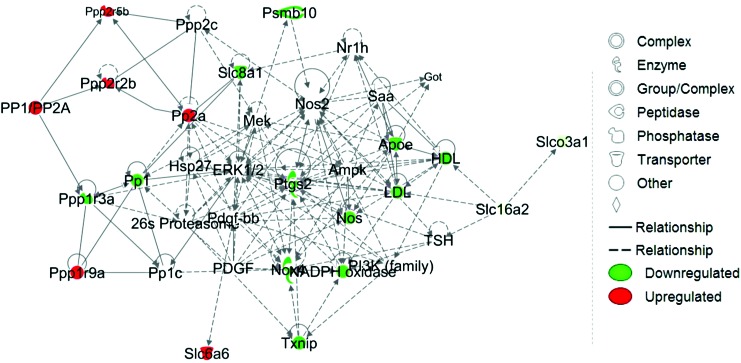

Here we review studies that have established specific mechanisms by which TSP1 and other matricellular proteins including CCN1, periostin, osteopontin, and ADAMTS1 regulate the production of nitric oxide, H2S, superoxide, and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Fig. 2A), and TSP1, conversely, regulates cellular redox signaling downstream of NO and H2S (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Overview of matricellular protein functions in cellular redox signaling. (A) Several matricellular proteins regulate the biosynthesis of redox molecules that mediate cell autonomous and paracellular signaling. TSP1 limits the activation of eNOS. TSP1, CCN1, and periostin regulate the activity of NADPH oxidases (Nox) that produce intracellular and extracellular superoxide (O2•−). TSP1 and CCN1 also regulate mitochondrial production of ROS. TSP1 regulates the biosynthesis of H2S by controlling the expression of CBS and CSE. ADAMTS1 and osteopontin regulate NO production by controlling the expression of iNOS. (B) TSP1 regulates cellular responses to endogenous or exogenous NO by inhibiting the activation of sGC and cGK and cellular responses to H2S by inhibiting known targets of protein sulfhydration and others that remain to be identified. (C) Redox signaling, in turn, regulates the gene expression, post-translational modification, secretion, and extracellular interactions of the indicated matricellular proteins and other extracellular matrix proteins. CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; cGMP; cGK, cGMP-dependent protein kinase; CSE, cystathionine γ-lyase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Redox and hypoxia signaling, in turn, regulate the expression, secretion, post-translational modification, and extracellular interactions of matricellular and other extracellular matrix proteins (Fig. 2C), which is discussed in more detail elsewhere in this Forum (34, 81, 119, 124, 128, 178). We review the emerging physiological functions of this regulation and the evidence that pathological dysregulation of matricellular protein expression contributes to acute and chronic disease states that are characterized by insufficient NO signaling and/or increased oxidative stress. Finally, we consider the progress made toward developing therapeutic approaches to restore NO function and other aspects of redox homeostasis by targeting the TSP1 receptor CD47.

II. Thrombospondin-1 and NO Signaling

A. Thrombospondin-1 structure and receptors

TSP1 is a trimeric protein consisting of identical subunits linked covalently through intersubunit disulfide bonds in the oligomerization domain (Fig. 3). The N-terminal domain of each subunit consists of a globular heparin-binding domain that interacts with several β1-integrins, sulfated glycoconjugates, several hyaluronan-binding proteins, and calreticulin. This is followed by a coiled-coil oligomerization domain, a von Willebrand C domain, three TSRs, three epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats, seven calcium-binding repeats, and the C-terminal lectin-like G-domain (Fig. 3) (23). The TSRs mediate binding of TSP1 to the cell surface receptor CD36 and to transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ). Additional low-affinity integrin binding sites are present in the TSRs and EGF repeats (21), and the EGF repeats mediate binding to the gabapentin receptor α2δ1 (49). In the presence of physiological Ca2+ concentrations, the calcium-binding repeats wrap around the G domain to form the “signature domain” of TSP1 (23). The signature domain mediates binding of TSP1 to CD47 and to stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) (48). The last Ca repeat also contains a RGD sequence that can be recognized by αvβ3 integrin but is cryptic in the Ca-replete protein (259).

FIG. 3.

Thrombospondin-1 structural domains and receptor binding sites. TSP1 is a homotrimer of ∼150 kDa subunits linked by interchain disulfide bonds. In each folded TSP1 subunit, the Ca-binding repeats wrap around the C-terminal G domain to form the signature domain of TSP1. Binding domains for TSP1 receptors that regulate redox signaling are indicated. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Specific peptide sequences have been identified that are involved in binding of TSP1 to several of its receptors. Although two TSP1 peptides containing a Val-Val-Met (VVM) consensus sequence were initially identified as potential CD47 binding sites and could be used to affinity purify CD47 (31, 46, 58), the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of TSP1 indicated that the VVM sequences are not exposed to solvent (121). A potential conformation change that exposes one of the VVM sequences has been proposed based on dynamic modeling studies (54), but structure function and mutagenesis studies have not been performed to determine whether the VVM sequences are involved in binding of native TSP1 to CD47. Furthermore, both TSP1-derived CD47 binding peptides have well-documented CD47-independent activities, and they cannot be used as reliable surrogates for TSP1 to investigate CD47 signaling (9, 129, 279).

In addition to the undefined protein–protein interaction, binding of TSP1 to CD47 requires post-translational modification of CD47 with a heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan at Ser64 (110). Because glycosylation can be cell-type specific, CD47 may vary in its ability to interact with TSP1 to control NO signaling. Such variation in functional activity to control NO signaling has been reported in a T cell line (202), but further studies are needed to define the molecular mechanism.

B. Thrombospondin-1 regulation of NO synthesis

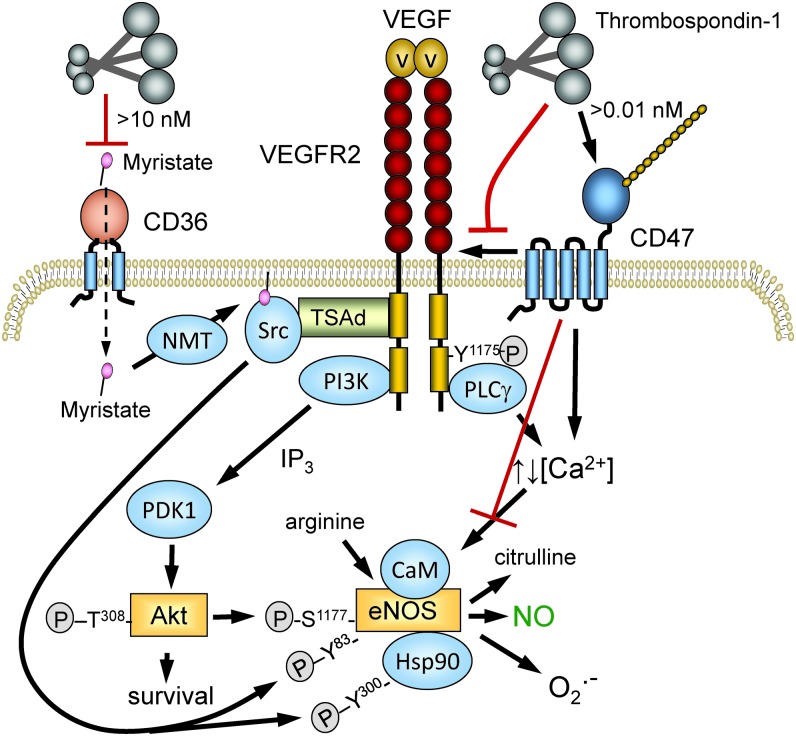

TSP1 regulates both the production of NO in vascular cells (Fig. 4) and responses of such cells to exogenous NO mediated by soluble guanylyl cyclase (Fig. 5). Depending on the cell type, TSP1 can regulate NO production by several mechanisms. In endothelial cells, TSP1 signaling inhibits the basal and acetylcholine-stimulated conversion of arginine to NO and citrulline by eNOS, whereas Thbs1−/− and Cd47−/− murine endothelial cells display increased basal eNOS activity compared with wild type (WT) cells (10). This result was subsequently confirmed in choroidal endothelial cells (53). Choroidal capillary endothelial cells from the eyes of Thbs1−/− mice had elevated phosphorylation of eNOS relative to WT cells, and intracellular NO in the null cells assessed using 4-amino-5-methylamino-2,7-difluorofluorescein (DAF) was sixfold higher than in WT cells. One should bear in mind that DAF is primarily detecting an oxidative product of NO rather than NO itself (176).

FIG. 4.

TSP1 regulation of NO synthesis. TSP1 binding to its receptor CD47 on the plasma membrane transduces signals by dissociating its lateral interaction with VEGFR2, by altering cytoplasmic calcium, and by other undefined pathways. Signaling downstream of VEGFR2 through Src and the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway controls the phosphorylation of eNOS at several sites and the phosphorylation of HSP90 associated with eNOS. TSP1, via CD47, also limits eNOS activation separate from effects mediated through VEGFR2. Altered cytoplasmic calcium regulates the binding of calmodulin, which controls the activity of eNOS and its production of NO versus O2•−. At higher concentrations (>10 nM), TSP1 inhibits CD36-mediated uptake of myristic acid (87), limiting substrate for NMT to acylate Src. This modification is necessary for optimal tyrosine phosphorylation of eNOS. NMT, N-myristoyl transferase; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

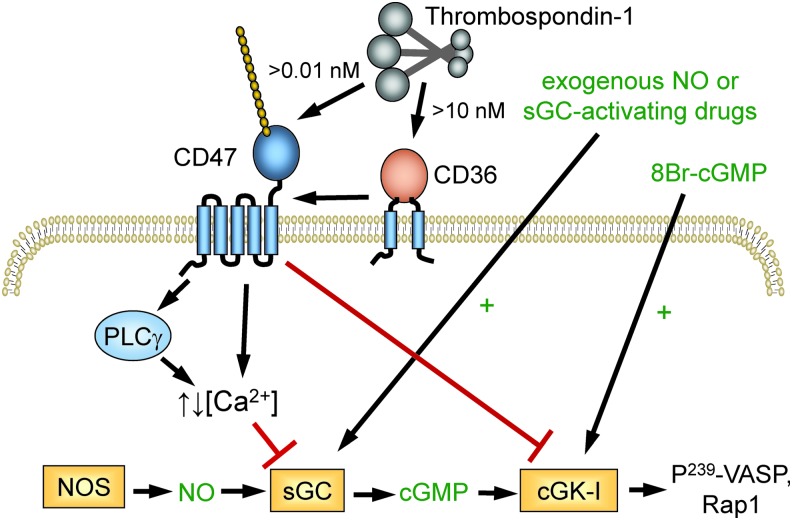

FIG. 5.

TSP1 regulation of cellular responses to NO. TSP1 binding to CD47 redundantly inhibits signaling induced by endogenous or exogenous NO at the level of sGC and inhibits cGMP-mediated activation of cGK. In platelets, this limits phosphorylation of VASP and Rap1-mediated integrin activation. Picomolar concentrations of TSP1 are sufficient to inhibit sGC via CD47 in vascular cells, whereas >10 nM TSP1 can engage CD36 to inhibit sGC activation in a CD47-dependent manner (92). VASP, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

eNOS is a highly regulated enzyme (55), and CD47 controls several of the pathways known to regulate eNOS activity. CD47 constitutively associates with the tyrosine kinase vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2) in endothelial cells and T cells (111). TSP1 binding to CD47 displaces CD47 from VEGFR2 and inhibits VEGFR2 auto-phosphorylation. Activated VEGFR2 controls several downstream pathways that control eNOS activation (Fig. 4). TSP1 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 (111). The PI-3-kinase/Akt pathway activates eNOS by phosphorylation of Ser1177 on eNOS (55), and TSP1 inhibits this phosphorylation (10). TSP1 inhibits VEGFR2-mediated phosphorylation of Src kinase at Tyr416 in a CD47-dependent manner (108). Src phosphorylates Tyr residues on eNOS and the associated Hsp90 that regulate eNOS activity, and TSP1 inhibits acetylcholine-mediated coassociation of eNOS and Hsp90 (10).

VEGFR2-mediated activation of phospholipase Cγ controls cytoplasmic calcium levels, which activate eNOS by inducing calmodulin binding (55). TSP1 signaling via CD47 has been reported to regulate calcium signaling in endothelial cells and T cells, but in opposing directions (10, 202). Therefore, the coupling between CD47 ligation by TSP1 and cytoplasmic calcium levels may be cell-type specific and may depend on whether ligand binding induces clustering of CD47 (155). Acylation by the fatty acid myristic acid is also important for maximal eNOS function (14, 143). In endothelial cells, TSP1, TSP1-derived peptides, and a CD36-binding TSP1 mimetic further limit eNOS activity by restricting myristic acid uptake through the fatty acid translocase and TSP1 receptor CD36 (87, 97) (Fig. 4), although the in vivo relevance of this remains to be determined.

Notably, Fei et al. also reported that inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression was elevated in Thbs1−/− choroidal endothelial cells relative to WT cells, suggesting that negative regulation of NO synthesis by TSP1 is not limited to eNOS (53), although it was not determined whether these findings in null cells were reversed by exogenous TSP1. Phosphorylation of STAT3 was markedly elevated in the Thbs1−/− cells, which was suggested to mediate the upregulation of iNOS, but additional studies are needed to confirm this mechanism. Negative regulation of STAT3 phosphorylation by TSP1 was also reported in colon tissues (69). Phosphorylation of STAT3 at Ser727 was increased twofold in Thbs1−/− colon tissue, and this was inhibited by a TSP1 mimetic designed to engage the TSP1 receptor CD36 (ABT898). Functional inhibition of STAT3 by TSP1 was further indicated by increased plasma interleukin (IL)-6 levels in the Thbs1−/− mice.

C. Thrombospondin-1 regulation of soluble guanylate cyclase and downstream targets

1. Soluble guanylate cyclase

TSP1/CD47 signaling also controls signaling downstream of NO by limiting the activation of the primary NO sensor/receptor soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) (Fig. 5) (93). This opens the potential for controlling signaling by NO produced by all three nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms and for regulating paracellular signaling wherein NO produced by one cell diffuses into an adjacent cell.

The mechanism by which CD47 signaling inactivates sGC remains to be fully characterized, but some details are known. Inhibition of sGC in immortalized T cells by a recombinant C-terminal fragment of TSP1 (E3CaG1) is mediated by increased cytoplasmic Ca2+, and elevation of Ca2+ after treatment with angiotensin-II resulted in a similar inhibition (202). The NO-insensitive state of sGC persisted in cell-free lysates and was prevented by the protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine, which suggests that TSP1/CD47 signaling induces an inhibitory phosphorylation of sGC. Inhibition of sGC by TSP1 was first reported in endothelial cells, but subsequent studies have confirmed this result in VSMCs (96), platelets (95, 162), T cells (202), and macrophages (206) of human and nonhuman origin, broadly implicating TSP1 as limiter of sGC activity.

The initial studies in endothelial cells suggested that TSP1 regulates sGC in a CD36-dependent manner (93). A recombinant type 1 repeats construct from TSP1 inhibited NO-induced chemotaxis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and cGMP accumulation in the cells, whereas a recombinant N-terminal region of TSP1 that engages integrins, calreticulin/low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1), and heparan sulfate proteoglycans did not. Furthermore, the CD36 antibody SMΦ, which is a reported agonist of CD36 signaling (37), significantly inhibited NO-stimulated proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and dermal microvascular endothelial cells and inhibited NO-induced cGMP accumulation. Similar inhibition of NO responses by the CD36-binding domain of TSP1 and the CD36 antibody was reported in VSMCs (96).

These studies established that engaging CD36 is sufficient to inhibit NO-stimulated activation of sGC. However, additional studies challenged the hypothesis that CD36 directly mediates this inhibitory activity of TSP1 (92). NO-stimulated vascular outgrowth was inhibited by TSP1 to the same extent in skeletal muscle explants from WT and Cd36−/− mice. TSP1 also inhibited NO-stimulated adhesion of VSMCs from Cd36−/− mice, and NO-stimulated accumulation of cGMP in these cells. Therefore, engaging CD36 is sufficient but not necessary to inhibit sGC activity.

In contrast, the TSP1 receptor CD47 is both necessary and sufficient to mediate inhibition of NO signaling by TSP1 (92). NO-stimulated vascular outgrowth from muscle tissue explants from Cd47−/− mice was completely insensitive to inhibition by TSP1. Ligation of CD47 by two CD47-binding peptides derived from TSP1 or by recombinant E3CaG1, containing the CD47 binding domain of TSP1, potently inhibited cGMP accumulation and functional responses to NO signaling. In the absence of exogenous TSP1, ligation of CD47 by the CD47 antibodies C1Km1 and B6H12 also inhibited NO signaling. This inhibitory activity of B6H12 is notable because B6H12 inhibits TSP1 binding to CD47 (84), suggesting that this antibody can, under TSP1-depleted conditions, act as a mimic of TSP1 and activate CD47 signaling to inhibit NO stimulation of sGC independent of its ability to prevent TSP1 binding to CD47.

Further examination of the roles of CD36 versus CD47 revealed that CD47 is also necessary for the inhibitory activity of CD36 ligands, but CD36 is not necessary for the inhibitory activity of CD47 ligands (92). A CD47-binding peptide from TSP1 and a recombinant C-terminal domain of TSP1 inhibited NO-stimulated cGMP accumulation in VSMCs from Cd36−/− mice, but a CD36 binding peptide did not inhibit cGMP accumulation in VSMCs from Cd47−/− mice. Finally, basal and NO-stimulated cGMP levels were elevated relative to WT in Cd47−/− cells but not in Cd36−/− cells. Therefore, CD47 is the necessary and sufficient receptor for mediating the inhibitory effect of TSP1 on NO-mediated activation of sGC. CD47 is also necessary for CD36-mediated inhibition of this pathway, but the molecular mechanism of this receptor cross-talk remains to be determined.

From a physiological perspective, another important distinction between the CD36 and CD47 pathways is their TSP1 dose dependence. Inhibition through CD47 is observed at 10 pM TSP1, but inhibition through CD36 requires 10 nM TSP1. Circulating TSP1 levels in healthy individuals are 100–200 pM. Therefore, physiological TSP1 concentrations are sufficient to tonically limit sGC activation in vascular cells through CD47 but not through CD36. The higher relative affinity of TSP1 for signaling through CD47 also has pathophysiological significance, which is demonstrated by the observation that Thbs1−/− mice and Cd47−/− mice show similar resistance to ischemic injuries and vascular remodeling after ischemic injury, but Cd36−/− mice rather than exhibiting an advantage over WT mice when subjected to the same ischemic injuries tended to be more sensitive to injury (90, 94).

A major focus of the pharmaceutical industry has been to develop drugs to overcome impaired NO signaling by directly activating sGC. TSP1/CD47 signaling in platelets inhibits sGC activation by the heme-dependent sGC activators YC-1 and BAY 41-2272 and the heme-independent activator meso-porphyrin IX (162). Because TSP1 expression is now known to be elevated in many of the diseases for which sGC activators could be useful, such pathological elevation in extracellular TSP1 levels may limit the efficacy of drugs that target sGC. However, YC-1 and BAY 41-2272 could overcome sGC inhibition by E3CaG1 in Jurkat T cells, suggesting that such regulation of sGC by TSP1 may be context dependent (202). However, the ability of these drugs to overcome TSP1 inhibition of sGC in primary vascular cells and in vivo remains to be determined.

CD47-dependent inhibition of sGC activation was also observed when cells were exposed to β-amyloid (163). β-Amyloid interacts with the TSP1 receptor CD36 but not with CD47. β-Amyloid inhibition also extends to activation of sGC by BAY 41-2272. The NO inhibitory activity of β-amyloid is maintained in Thbs1−/− endothelial cells, indicating that this effect is TSP1 independent (163). Given the role of β-amyloid in certain neurodegenerative processes, these findings in vascular cells invite further inquiry.

2. cGMP-dependent protein kinase

TSP1 also inhibited endothelial cell adhesion stimulated by 8-Br-cGMP, indicating that TSP1 has a second inhibitory target downstream of sGC (93). TSP1 limited the antithrombotic activity of NO and the cell-permeable cyclic analogue 8-Br-cGMP in WT platelets (95) (Fig. 5). 8-Br-cGMP activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase, and this was identified as the downstream target of CD47 signaling based on the ability of TSP1 to inhibit phosphorylation of the cGMP-dependent protein kinase-I selective substrate Arg-Lys-Arg-Ser-Arg-Ala-Glu stimulated by NO or by 8-Br-cGMP.

TSP1 also inhibited phosphorylation of the cGMP-dependent protein kinase target protein vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) at Ser239 that was induced by 8-Br-cGMP. The downstream activation of the GTPase Rap1 was also inhibited in a CD47-dependent manner. The molecular mechanism by which CD47 inhibits cGMP-dependent protein kinase remains to be determined. To summarize, TSP1 via CD47 acts redundantly on the canonical NO pathway, limiting production, receptor activation, and cGMP signaling.

D. Physiological functions of TSP1/CD47 regulation of NO signaling

1. Platelet homeostasis

NO is a physiological inhibitor of platelet activation and aggregation. NO is produced by eNOS expressed in platelets and vascular endothelium (199). The resulting tonic inhibition of platelet activation contributes to preventing thrombosis but must be suppressed for platelets to effectively limit bleeding at sites of vascular injury. Because TSP1 is a major protein in platelet α-granules and is rapidly released after their activation by thrombin, it was an obvious candidate for mediating this function.

Earlier studies reported contradictory evidence regarding the role of TSP1 in platelet activation (135, 280), and the first evaluation of platelet function in Thbs1−/− mice reported normal hemostatic function as assessed by tail bleeding and thrombin activation of washed platelets (127). Therefore, TSP1 was concluded to not be required for normal platelet function. However, the buffer used to assess activation of the washed platelets did not provide the arginine required for platelet eNOS to maintain physiological NO concentrations. When this experiment was repeated in the presence of either arginine or an exogenous NO donor, Thbs1−/− and Cd47−/− platelets showed clear defects in thrombin-mediated activation (95). Correspondingly, cGMP levels were elevated in Thbs1−/− platelets but restored to normal levels by addition of exogenous TSP1 or a CD47-binding peptide. Concentrations of TSP1 that limited platelet NO signaling were comparable with those that circulate in plasma.

Consistent with its capacity to engage in multiple interactions, other studies have revealed additional physiological functions of TSP1 in platelet hemostasis that are independent of NO signaling (13), but an NO-dependent prothrombotic activity is one clear physiological function of platelet TSP1. This function is consistent with the evolutionary record. The presumed gene duplication that gave rise to TSP1 in tetrapods (2) was followed soon thereafter in amphibians and higher land-dwelling vertebrates by the gene duplication that yielded eNOS to enable local vascular control of NO production in high pressure circulatory systems (274) and the appearance of CD47, presumably by a recombination event that joined a primordial IgV domain with a presenilin transmembrane domain (208, 210).

2. Vascular perfusion

Functional magnetic resonance imaging of WT and Thbs1−/− mice provided the first evidence that TSP1 functions as a physiological regulator of NO in the local control of tissue vascular perfusion (85). Functional imaging of blood oxygenation in the proximate hind limb muscle of mice was assessed after intestinal administration of a rapidly releasing NO donor. The resulting increase in perfusion in the Thbs1−/− mice was faster and greater than (roughly double) that observed in WT mice. This demonstrated that endogenous TSP1 in the vasculature constitutively limits responsiveness to NO-mediated vasodilation by ∼50%. cGMP levels were correspondingly elevated in Thbs1−/− tissues and VSMCs.

Mechanistic studies demonstrated that TSP1 blocked the dephosphorylation of myosin light chain-2 induced by treating these cells with NO and thereby promoted F-actin assembly and contraction of the smooth muscle cells. Notably, the elevated tissue cGMP levels found in young male Thbs1−/− mice persisted as those mice were aged to 12–16 months, but cGMP levels fell significantly with age in male WT mice (86), consistent with the reported elevations in tissue TSP1 and CD47 levels with aging (19, 105, 207, 213). Thus, TSP1 physiologically opposes the activity of NO to regulate vascular tone, but this balance becomes perturbed with increasing age. The reasons for the progressive and, in regard to NO signaling, maladaptive upregulation of TSP1 with age are not known.

3. Central blood pressure

Analysis of blood pressure using telemetry implants in young Thbs1−/− and Cd47−/− mice revealed that the physiological regulation by this pathway extends to control of central blood pressure (91). Thbs1−/− mice have decreased pulse pressure than WT mice, and during the active period of their diurnal cycle they exhibited increases in heart rate and central diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure. Cd47−/− mice have normal pulse pressure but lower resting mean arterial pressure, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure than WT mice (10). Further studies of responses to vasoactive agents in the mice and isolated perfused vessels confirmed that endogenous TSP1 in the vessels and in circulation functions as a pressor agent supporting blood pressure.

Loss of this pressor activity in Thbs1−/− and Cd47−/− mice increases the sensitivity of these mice to pharmacological challenges that impair blood pressure homeostasis, including isoflurane anesthesia, nitrovasodilators, and chemical sympathectomy with hexamethonium chloride (91), suggesting a major role for the autonomic outflow track in stabilizing blood pressure in null animals lacking the supporting role of the TSP1/CD47 axis. Therefore, in healthy young animals, TSP1 and CD47 play relatively minor roles in blood pressure homeostasis at rest, but their function is more important for cardiovascular responses required for normal activity and to adapt to stress conditions.

E. NO regulation of TSP1 expression

In parallel with the developing understanding that TSP1 regulates NO signaling, evidence was accumulating suggesting a negative feedback loop, wherein NO controls expression of TSP1. Indirect evidence for NO inhibition of TSP1 expression was first provided by studies in endothelial cells. Endothelial cells treated with the arginine analogue l-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME) to suppress endogenous NO production displayed increased TSP1 expression (193). Additional studies revealed a more complex regulation of TSP1 by NO in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (205).

Treatment of human umbilical vein endothelial cells with exogenous NO using 0.1–1 μM diethyltriamine NONOate (DETA/NO) suppressed TSP1 mRNA and protein expression at 2 and 24 h, respectively. Inhibition could be reversed by treating cells with the sGC inhibitor 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazole[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ, IC50 = 20 nM). This is consistent with the finding that inhibition of glucose-induced TSP1 expression in mesangial cells by an NO donor was reversed by ODQ and by the inhibitor of cGMP-dependent protein kinase Rp-8-pCPT-cGMPS (291). Constitutive expression of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in mesangial cells also prevented induction of TSP1 expression in mesangial cells (293). Therefore, inhibition of TSP1 expression in mesangial and endothelial cells by nanomolar concentrations of exogenous NO is mediated by sGC.

In a rat model of mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, oral administration of a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, to increase the half-life of cGMP, resulted in decreased renal TSP1 expression (76). The mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor U0126 (1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(o-aminophenylmercapto)butadiene) partially reversed low dose NO-mediated inhibition of TSP1 mRNA and protein expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, indicating that the MEK/extracellular-regulated protein kinase (ERK) pathway is also involved in negative regulating TSP1 expression (205). Consistent with this hypothesis, addition of l-arginine to the medium increased ERK phosphorylation, and L-NAME inhibited ERK phosphorylation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

DETA/NO concentrations between 1 and 100 μM modestly increased TSP1 protein expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, whereas 1000 μM DETA/NO strongly suppressed TSP1 expression, suggesting a triphasic regulation of TSP1 expression by NO (205). The inhibition of TSP1 expression at 1000 μM DETA/NO coincided with increased phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15 and increased expression of MAP kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP1/DUSP1). Oxidative stress induces MKP1/DUSP1 expression in a p53-dependent manner (146), and both alterations are likely mediated by reactive nitrogen species (RNS) rather than directly by NO (272). MKP1 levels varied inversely with ERK phosphorylation across the NO dose response, suggesting that MKP1 inhibits the ERK-dependent regulation of TSP1 expression.

The inhibition of TSP1 expression by high concentrations of NO donors or the resulting RNS has been replicated in a second cell type. Treatment of rat renal mesangial cells with the NO donor and nitrosating agent S-nitroso-l-glutathione at 500 μM resulted in decreased TSP1 mRNA expression (295). Downregulation of TSP1 mRNA was confirmed using rat and human mesangial cells treated with the more specific NO donor spermine-NONOate. Downregulation was sustained from 4 to 24 h. Further studies using human mesangial cells in medium containing 30 mM glucose and treated with spermine-NONOate, DETA/NO, or S-nitroso-N-acetyl-dl-penicillamine demonstrated downregulation of TSP1 protein expression.

Data indicate that decreased/absent TSP1 expression is associated with enhanced NO responses in vascular cells and platelets (95). Furthermore, male Thbs1−/− and Cd47−/− mice enjoy elevated NO signaling, and this is associated with loss of TSP1 induction with injury or hypoxia compared with WT. These and other findings suggest possible feedback regulatory control of TSP1 by anti-inflammatory low dose NO.

VSMC chemotaxis to a supraphysiological concentration of TSP1 (20 μg/ml) was altered by exogenous NO, with low concentrations limiting TSP1 chemotaxis and high concentrations enhancing it (227). Similarly, VSMCs treated with the NO-prodrug sodium nitroprusside were resistant to TSP1-stimulated chemotaxis. Endothelial progenitor cells exposed to laminar flow, a known activator of eNOS, upregulated NO concurrent with downregulation of TSP1 protein (7). In contrast to these results in primary vascular and renal cells, treatment of human hepatoma3 B cancer cells with the NO prodrug O2-(2,4-dinitrophenyl) 1-[(4-ethoxyxarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium 1,2-diolate (1 to 10 μM) increased TSP1 mRNA expression and cell surface expression of the TSP1 receptor CD36 (44). Conversely, treatment of NIH 3T3 cells with high concentrations of NO (1 mM DETA/NO) for 24 h suppressed TSP2 promoter activity and mRNA (149).

Beyond cell culture, limiting NO for 28 days in male rats by daily feeding of L-NAME in the drinking water was associated with increased TSP1 protein expression in distal mesenteric arteries and elevated blood pressure (17). In a small clinical study, 4 weeks of aerobic training in healthy young men was associated with increased eNOS protein expression in vastus lateralis muscle samples. Although TSP1 protein levels were not significantly changed, TSP1 levels trended lower in postexercise samples (77).

The mechanism by which NO limits TSP1 expression at the pre- and post-transcriptional levels remains to be determined. Furthermore, it will be interesting to consider the effects of NO and NO surrogate drugs on changes in TSP1 and TSP1 receptor expression as a possible index of clinical effect. Some data suggest a role for ROS to increase TSP1 expression (infra vide Section VI). If confirmed, the chemical quenching of superoxide by NO may represent yet another mechanism by which the biogas limits TSP1 expression.

III. NO Signaling and Other Matricellular Proteins

A. NO signaling and other thrombospondins

1. Regulation of NO signaling

The C-terminal domain of TSP1 that interacts with CD47 shares 53–82% sequence homology with the other four members of the TSP family, the highest being with TSP2 (23). This suggested that TSP2 and other TSPs may also inhibit NO signaling via interaction with CD47. A comparison of recombinant signature domains of TSP1, TSP2, and TSP4 showed moderate competition between the signature domains of TSP2 and TSP1 for binding to cells expressing CD47 but no significant inhibition by the signature domain of TSP4 (84). Consistent with these data, the three paralogs showed decreasing potency for inhibiting NO-stimulated cGMP accumulation in VSMCs in the order TSP1>TSP2>TSP4.

One study has also implicated CD47 as a receptor for cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) (211). Attachment of ligament cells to COMP was inhibited by a peptide derived from the globular C-terminal domain of COMP (SFYVVMWK) that resembles the known CD47-binding peptide 4N1 from TSP1 (RFYVVMWK). A CD47 blocking antibody also inhibited adhesion, but the study did not establish that CD47 directly binds to COMP or exclude the possibility that the ligands including TSP1, by engaging CD47 on the ligament cells, indirectly inhibit adhesion by inactivating αvβ3 integrin, which also serves as a COMP receptor on these cells.

To assess whether TSP2 contributes significantly to regulating physiological NO signaling, primary lung endothelial cells were prepared from Thbs2−/− mice (84). No difference was seen in basal cGMP levels, but surprisingly NO-stimulated cGMP was moderately but consistently lower in the Thbs2−/− cells. No difference in NO-stimulated proliferation was observed. These results demonstrate that endogenous TSP2 does not contribute significantly to regulating basal NO signaling in vascular endothelial cells, but it should be noted that expression of TSP2 in these cells was significantly lower than that of TSP1, which may mask potential inhibitory signaling from TSP2. Thbs2−/− mice also exhibited no significant advantage over WT mice when analyzed for recovery from an ischemic injury (84).

Thus, to date no physiological or pathophysiological regulation of NO signaling by TSP2 has been demonstrated, but conditions may be found in the future wherein increased TSP2 expression is sufficient to inhibit NO signaling. However, given the homology in structure and domains, it is predicted that TSP2 will act via CD47 to limit NO in such instances.

2. Regulation of expression by NO

Studies in endothelial cells lacking the monooxygenase cytochrome P450 1B1 first implicated regulation of TSP2 expression by eNOS-derived NO (266). Genetic evidence for this regulation was later provided using Nos3−/− mice, which exhibited elevated TSP2 expression in ischemic and wound tissues (149). Studies using Akt1−/− mice demonstrated that Akt1 signaling, which phosphorylates eNOS, also negatively regulates TSP2 expression at sites of injury (8). However, a recent study reported elevated TSP2 levels produced by Thbs1−/− choroidal endothelial cells despite having elevated eNOS phosphorylation and NO production as assessed by 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate fluorescence (53).

Additional RNS may be involved in the observed induction of TSP2 because iNOS was also strongly induced in the Thbs1−/− cells, and 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein is currently believed to directly detect NO2• rather than NO (176). Further investigation is needed to identify the RNS that proximally regulates TSP1.

B. Regulation of iNOS-derived NO production and signaling

1. ADAMTS1

A recent study has extended matricellular protein regulation of NO signaling to the TSR family. Marfan syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by inherited or sporadic mutations in fibrillin-1 (223). Fibrillin-1 provides a scaffold for deposition of elastin, and in Marfan syndrome patients the resulting defect in elastic tissue integrity is associated with the formation of thoracic aortic aneurysms (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

ADAMTS1 regulation of iNOS. Mutation of fibulin-1 (Fbn1) that causes Marfan syndrome results in decreased expression of ADAMTS1 (186). ADAMTS1 cleaves proteins including SDC4 that regulate the induction of NOS2 via an Akt-NF-κB. The resulting production of NO increases proteolytic cleavage of elastin via MMP9, and the loss of elastic fibers in the aorta leads to formation of aneurysms. MMP9, matrix metalloproteinse-9; SDC4, syndecan-4. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Expression of the matricellular protease ADAMTS1 was found to be lower in the medial layer of aortic sections from patients with Marfan syndrome, whereas iNOS (NOS2) expression was generally elevated at the same location (186). A role of altered ADAMTS1 expression in Marfan syndrome was suggested by similarities in the aortic pathology of Adamts1+/− and Fbn1C1039G/+ mice. Aortic sections from Fbn1C1039G/+ mice had reduced levels of ADAMTS1, comparable with that seen in Marfan syndrome patients, whereas aortic NO levels and NOS2 expression were elevated. Aortic NO levels and NOS2 expression were similarly elevated in the Adamts1+/− mice. Lentiviral siRNA knockdown of ADAMTS1 in WT mice rapidly induced aortic dilation, hypotension, and medial degeneration, which could be prevented by treating the mice with the pan-NOS inhibitor L-NAME.

In contrast, siRNA knockdown of ADAMTS1 in Nos2−/− mice exhibited no aortic pathology, and aortic NO levels remained normal. Specific inhibition of NOS2 using the selective inhibitor 1400 W also prevented aortic dilation when used to treat both young and aged Adamts1+/− or Fbn1C1039G/+ mice. The elevated levels of NO produced by NOS2 were proposed to increase MMP9-mediated fragmentation of elastin because MMP9 activation and elastin fragmentation in the aorta of Adamts1-deficient mice were sensitive to NOS inhibition.

Others have reported that NO (as S-nitrosoglutathione, GSNO) enhances the expression of MMP9, its inhibitor TIMP1, and elastin in VSMCs (240). In addition, the resulting active MMP9 can lead to fragmentation of other matricellular proteins in the vessel wall, including osteopontin and the TSP1 receptor CD36 (38, 141). These studies suggest that a selective therapeutic NOS2 inhibitor could be protective for patients with Marfan syndrome. However, such a therapeutic strategy would need to be balanced against compromising the role of NOS2 in host defense.

The effects of ADAMTS1 knockdown on NOS2 expression in VSMCs were mediated by increased Akt phosphorylation and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation (186). Inhibition of Akt signaling in Adamts1+/− mice using the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor AZD8055 decreased aortic dilation, inhibited NO production in the aortic wall, and reduced NOS2 levels. It is interesting to consider whether mTOR blockade could provide therapeutic benefit to Marfan syndrome patients. However, as mTOR is a proximate promoter of VSMC growth, long-term mTOR blockade could lead to vascular hypoplasia, although this may be of benefit in conditions such as pulmonary hypertension (PH) wherein pulmonary vascular smooth muscle growth is accentuated (see ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02587325).

2. Osteopontin and NOS2 signaling

Earlier characterization of the matricellular protein osteopontin revealed that it inhibits NO synthesis induced by interferon-γ and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in primary mouse kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells (82). Purified osteopontin inhibited NOS2 mRNA and protein expression in these cells. Similar inhibition of NOS2 induction by inflammatory mediators was reported in RAW264.7 macrophages (218) and rat thoracic aortas (226). Conversely, LPS in the presence of NO induced transcription of the Opn gene, suggesting a negative function of osteopontin to limit inflammatory production of NO (67). A similar negative feedback role was found for limiting NO production in rat pancreatic islets and RINm5F β cells (6).

Several correlative studies support a protective role of osteopontin in animal injury models and patients, but the strongest evidence for an NO-dependent protective role comes from a liver ischemia–reperfusion model. After 45 min of warm hepatic ischemia, Opn−/− mice exhibited elevated release of liver enzymes, increased necrosis, and increased expression of NOS2 and inflammatory cytokines (189).

Two potential mechanisms were identified: (i) loss of osteopontin cell autonomously impairs hepatocyte resistance to stress and (ii) osteopontin limits the production of toxic iNOS-derived NO by macrophages. The relative contributions of these mechanisms to the protective function of osteopontin remain to be determined.

In contrast, osteopontin was proposed to enhance lung injury secondary to intestinal ischemia–reperfusion, and an osteopontin blocking antibody protected mice from this injury (73). Comparing renal ischemia–reperfusion in WT versus Opn−/− mice found no differences in functional impairment in the first 7 days after reperfusion, but collagens I and IV expression was decreased and macrophage infiltration was significantly diminished in the nulls consistent with decreased inflammation and fibrosis (191). Another study found decreased natural killer (NK) cell recruitment in reperfused kidneys of Opn−/− mice, and osteopontin activated NK cells to kill tubular epithelial cells in vitro (310). Therefore, consistent evidence is currently lacking to conclude that osteopontin regulation of NO production has a major role in ischemic injuries or that osteopontin is tissue protective.

Characterization of bone cells from mice lacking osteopontin revealed a deficit in NO production, assessed as nitrite using the Griess reagent, when the cells were subjected to pulsatile flow (40). However, it is unclear which NOS isoform is regulated by osteopontin in these cells.

3. Regulation of other matricellular protein expression by NO

Induction of NOS2 in rat mesangial cells by treatment with IL-1β and TNFα resulted in a cAMP-dependent decrease in SPARC mRNA and protein levels (287). SPARC expression was also decreased in cells treated with NO donors, and downregulation of SPARC in kidneys of rats treated with endotoxin was reversed by the NOS2-specific inhibitor L-N6-l-(iminoethyl)-lysine dihydrochloride.

A subsequent study identified that the SPARC/BM-40 family member secreted modular calcium-binding protein 1 (SMOC1) as another matricellular protein downregulated by NO signaling in rat mesangial cells (47). The same NOS2 inhibitor prevented downregulation of SMOC1 in kidneys of nephritic rats. Expression of TSP2 in ischemic tissues is regulated by NOS3-dependent NO signaling (149).

Treatment of human meniscal cells obtained from nondegenerative hip meniscus with the NOS inhibitor L-NAME inhibited the mRNA expression of two ADAMTS family members that function as aggrecanases (ADAMTS-4 and −5) (231). This was identified as an upregulated catabolic pathway associated with induction of autophagy by the NOS inhibitor. An earlier study using bovine cartilage explants reported no effect of inhibiting NOS using L-NG-monomethyl arginine citrate on ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 mRNA expression, but found that their enzymatic activity induced by TNFα was significantly inhibited (255). The mechanism by which NO post-transcriptionally regulates ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 remains to be defined.

IV. Thrombospondin-1 Regulation of H2S Biosynthesis and Signaling

A. Role of H2S in T cell activation

H2S is a toxic gas at high concentrations, but it is also synthesized in mammalian tissues by three enzymes that yield physiological H2S concentrations of 0.1–2 μM (233, 234). Several functions of endogenous H2S signaling have been identified using mice lacking specific genes required for H2S biosynthesis. H2S can act as an intracellular and paracrine signaling molecule through sulfhydrylation of thiols on specific target proteins (172, 173) and by formation of persulfides and polysulfides (66, 83). H2S plays both pro- and anti-inflammatory roles in immune cells. This apparently contradictory statement can be rationalized by the bimodal dose dependence of H2S responses. Higher concentrations of H2S generally induce proinflammatory responses, whereas concentrations <10 μM are anti-inflammatory. H2S inhibits IL-2 production by and proliferation of T cell lymphocytes (283). Similar effects were also reported for polymorphonuclear cells, wherein 1 mM H2S induced PMN apoptosis (153).

Duration of H2S exposure is also important in defining its effects on cells. For example, the slow-releasing H2S donor GYY4137 inhibited an LPS-induced proinflammatory response and increased expression of the anti-inflammatory chemokine IL-10, whereas rapid exposure to H2S produced from NaHS induced the opposite responses on the same type of cells (298). In addition, H2S effects can be species- and organ-specific, depending on differences in the activities of different H2S biosynthetic and catabolic pathways (290).

Higher pharmacological concentrations of H2S inhibit T cell functions by inhibiting mitochondrial function. Exposure of Jurkat T cells to 1–5 mM NaHS at pH 6.0–8.0 induced blebbing and apoptosis by activation of the Rho-Rock pathway and cleavage of caspase-3 and poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) (107). In contrast, H2S at physiological concentrations (<10 μM) is a positive physiological enhancer of T cell function (166) (Fig. 7). In primary mouse CD3+ T cells, OT-II CD4+ T cells, and the human Jurkat T cell line, physiological levels of H2S potentiated T cell receptor-induced activation. H2S at 50–500 nM enhanced T cell activation assessed by CD69 expression, IL-2 expression, and CD25 levels. H2S dose-dependently enhanced T cell receptor-stimulated proliferation. Furthermore, activation increased the capacity of T cells to make H2S by increasing expression of cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) and cystathionine β-synthase (CBS). Disrupting this response by using siRNA to target these enzymes impaired T cell activation and proliferation, which could be rescued by the addition of 300 nM H2S. At physiological concentrations, H2S also induced formation of the immunological synapse by altering cytoskeletal actin dynamics in the microtubule organizing center during T cell activation (166).

FIG. 7.

TSP1/CD47 signaling in T cells. Presentation of antigen in the context of MHC induces the formation of the immunological synapse and activation of TCR signaling through mediators, including LAT and ZAP70. CD47 signaling acts downstream of these mediators to limit the induction of multiple genes involved in T cell activation and effector function. In addition to cell autonomous inhibition, CD47 signaling inhibits expression of genes encoding the T cell cytokine IL-2 and the α-subunit of the IL-2 receptor (CD25). CD47 also limits activation-dependent induction of the H2S biosynthetic enzymes CBS and CSE. In T cells their activity is required for reorientation of the MTOC, which is required for immune synapse formation. In cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, CD47 regulates expression of the effector GZMB, which mediates antigen-dependent killing of tumor cells. GZMB, granzyme B; IL, interleukin; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; MTOC, microtubule-organizing center; TCR, T cell receptor. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

B. TSP1 inhibition of H2S biosynthesis in T cells

Analogous to its inhibition of NO signaling, TSP1 signaling through CD47 inhibits H2S signaling in T cells. Murine Thbs1−/− T cells are more sensitive to activating signals in the presence of H2S, resulting in elevated levels of IL-2 and CD69 mRNA and cell proliferation than WT-activated murine T cells (164). The increased IL-2 and CD69 expression is reversed by physiological concentrations (0.2–2 nM) of exogenous TSP1. Resting and activated Thbs1−/− murine T cells have upregulated CBS and CSE mRNA expression. This suggested that TSP1 endogenously regulates H2S signaling by limiting the expression of Cbs and Cse genes, which, in turn, limits T cell activation.

A CD47-binding peptide derived from TSP1 (7N3, FIRVVMYEGKK) recapitulated the inhibitory activity of TSP1, whereas Cd47−/− murine T cells were resistant to inhibition by TSP1 (164). This indicates that TSP1 signaling through CD47 has a homeostatic inhibitory role that limits the autocrine role of H2S in T cell activation and, therefore, may play a role in inflammatory diseases that are associated with induction of H2S.

C. Potential role of TSP1 in other H2S signaling

H2S signaling also plays important roles in angiogenesis, including activation of VEGFR2 (267). CBS expression is necessary for optimal VEGF signaling (222). H2S is also a physiological regulator of VSMCs (104). Extrapolating from its regulation of H2S biosynthesis and signaling in T cells, TSP1 could be a global antagonist of H2S biosynthesis and signaling. If so, TSP1 would be an even more comprehensive regulator of angiogenesis and blood flow than indicated by its highly redundant inhibition of VEGF/NO signaling pathways (88). The emerging role of H2S signaling in cancer also merits future studies to investigate whether TSP1 and CD47 regulate tumor cells in a H2S-dependent manner (261).

V. H2S Regulation of Matricellular Protein Expression

A. Osteopontin

Osteopontin has emerged as an important target of H2S signaling in several cell types, but the nature of this regulation appears to be cell-type specific. Osteopontin plays a major role in regulation of vascular calcification and mineral depositions in humans (61). During vascular calcification of arteries, smooth muscles cells, pericytes, fibroblasts, and macrophages transform into an osteoblast-like phenotype, which is characterized by upregulation of osteopontin. During calcification induced with vitamin D3 plus nicotine in rats, aortic H2S content and CSE mRNA were decreased significantly but osteopontin mRNA was increased (302). Daily treatment of vitamin D+nicotine exposed rats with NaHS at 2.8 or 14 μmol/kg downregulated osteopontin mRNA to control levels. This suggests that H2S inhibits mRNA expression of osteopontin. Similarly, osteopontin mRNA was upregulated in hyperhomocysteinemia, and H2S/CSE expression was downregulated (294). This led to enhanced proliferation of VSMCs from rat thoracic aortas. Treatment with 100 μM NaHS significantly decreased proliferation of VSMCs via an ERK1/ERK2-dependent pathway and partially inhibited the induction of osteopontin by homocysteine.

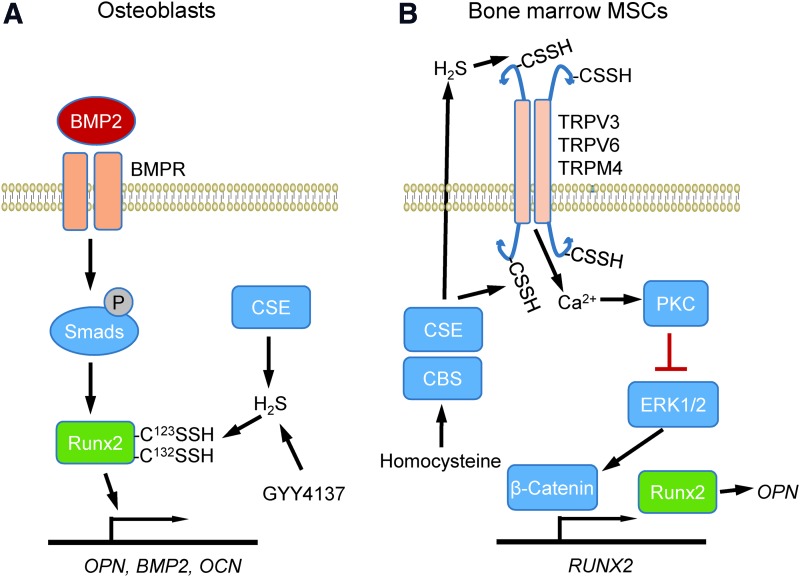

In contrast, endogenous H2S produced by CSE induces differentiation and maturation of primary osteoblasts, resulting in induction of osteopontin and BMP2 expression (315). This is mediated by sulfhydration of the transcription factor RUNX2 at Cys123 and Cys132 and results in elevated BMP2, osteopontin, and osteocalcin expression (Fig. 8A). The H2S donor GYY4137 induced the same sulfhydration-dependent induction, whereas mutation of these Cys residues on RUNX2 or treatment with the CSE inhibitor dl-propargylglycine prevented RUNX2 sulfhydration, nuclear localization, and transactivation. Delivery of CSE using an adenoviral vector facilitated healing of fractured femurs in treated rats (315). The contrast between this study and those already mentioned, suggesting inhibition of osteopontin expression by H2S, may reflect a biphasic dose response, wherein physiological H2S induces osteopontin but supraphysiological concentrations are inhibitory.

FIG. 8.

Regulation of osteopontin expression by H2S. (A) Studies in osteoblasts identified CSE as the major source of endogenous H2S biosynthesis mediating induction of OPN, BMP2, and OCN. BMP2 induces these genes via SMAD signaling that activates the transcription factor RUNX2, but this induction is impaired if H2S synthesis is inhibited. Cys123 and Cys132 were identified as sulfhydration targets on RUNX2 that mediate this activity. (B) In bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, H2S sulfhydrates Cys residues on the calcium channels TRPV3, TRPV6, and TRPM4. This modification controls calcium influx, which controls transcriptional activation of the RUNX2 gene via PKC and the MAP kinase ERK1/2. BMP2, bone morphogenetic protein-2; OCN, osteocalcin; OPN, osteopontin; PKC, protein kinase C. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Studies using bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) identified another sulfhydration target that controls the expression of osteopontin (145) (Fig. 8B). H2S deficiency has been linked with a perturbed balance between osteoblast and osteoclast cells that leads to osteopenia and bone marrow MSC impairment in mice. Injection of the H2S donor GYY4317 rescued abnormal osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and bone mineral density in Cbs+/− mice. The H2S deficiency perturbed Ca2+ influx mediated by TRPV6, TRPV3, and TRPM4 channels, which are regulated via sulfhydration. Mass spectrometry identified sulfhydration of TRPV6 at Cys172 and Cys329. Overexpression of the double mutant TRPV6C172+C329mu reduced H2S donor-induced protein kinase C phosphorylation and downstream ERK-dependent activation of β-catenin, which induces RUNX2 and in vitro osteogenic differentiation. These data suggest that H2S is essential for maintaining a homeostatic function of osteopontin for differentiation of MSCs during osteogenesis.

B. Tenascin C

Complementary to regulation of H2S production and signaling by TSP1 in the extracellular matrix, several recent studies implicate H2S as an important regulator of extracellular matrix remodeling that may involve additional matricellular proteins. H2S treatment of spontaneous hypertensive rats and isolated VSMCs inhibited collagen levels and hydroxyproline secretion (312). H2S treatment also protected lung tissues from ventilator-induced lung injury (249). Gene enrichment analysis of microarray data showed significant regulation of extracellular matrix remodeling pathways, including altered expression of the matricellular protein tenascin C.

Chronic lung fibrotic diseases increase deposition of extracellular matrix, including collagens, proteoglycans, and adhesive glycoproteins. These structural alternations in lung tissues resemble those found in hibernating animals during the transition from torpor to arousal state. The golden Syrian hamster is an accepted model for lung remodeling during hibernation (265). Cooling of hamster cells increased endogenous H2S production by CBS. During the torpor phase, H2S suppressed immune responses and elevated collagen and CBS expression, which became normalized during euthermia or arousal state. Treating golden Syrian hamsters with exogenous H2S inhibited gelatinase activity, potentially by quenching of Zn2+ and increased expression of CBS (264). This suggests a central role for lung extracellular matrix remodeling in the protective function of H2S during hibernation.

C. Laminin-γ1

H2S inhibited glucose-induced laminin γ1 synthesis in mouse podocytes and kidney proximal tubular epithelial cells via the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-AMP kinase pathway (131). CBS and CSE expression was significantly reduced in mice with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The resulting deficiency in H2S led to increased glucose-dependent inhibition of AMP kinase and activation of mTORC1. This dysregulation, in turn, resulted in increased synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins and renal cell hypertrophy. Similar results were reported for mouse glomerular endothelial cells cultured with low and high glucose, wherein H2S treatment downregulated matrix protein expression induced by high glucose (118). H2S treatment increased phosphorylation of LKB1-AMPK and induction of several autophagy genes. The latter result suggests a mechanistic link between the ability of TSP1/CD47 signaling to inhibit both H2S biosynthesis (164) and autophagy responses (244).

NO and cGMP signaling also regulates the expression of laminin γ1 and other extracellular matrix proteins in an AMP kinase-dependent manner (130). In some contexts, H2S enhances NO signaling (262). Further studies are needed to determine how simultaneous regulation of NO and H2S signaling by TSP1/CD47 influences the cross-talk between these pathways. In addition, the proangiogenic effects of H2S, by increasing VEGF expression and VEGFR2 phosphorylation in endothelial cells and decreasing levels of the antiangiogenic soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), may be relevant to this model (79, 289).

VI. TSP1 Regulation of ROS

A. TSP1 and ROS signaling in inflammatory cells

1. Historical context

Studies have identified roles for several matricellular proteins in regulating intracellular or extracellular ROS production, although the chemical identity of that ROS often remains unclear (Table 1). TSP1 enhanced the production of extracellular superoxide by neutrophils stimulated by the bacterial chemoattractant peptide fMLP (257). The identity of superoxide was confirmed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) inhibition of the detected reduction of cytochrome C. A similar enhancement was found when TSP1-treated monocytes were exposed to TSP1 antibodies (224). A subsequent study using fMLP-stimulated PMN from a patient with leukocyte adhesion deficiency suggested that the ability of PMN to spread on a substrate coated with TSP1 regulated superoxide production (256).

Table 1.

Matricellular Proteins and Reactive Oxygen Species Characterization

| Cell type | Matricellular protein | Reactive oxygen speciesa | ROS characterization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil | TSP1 | Superoxideb | Cytochrome c | (257) |

| Monocytes | TSP1 | ROS | Luminol | (224) |

| Neutrophils | TSP1 | H2O2 | Scopoletin oxidation by horseradish peroxidase | (256) |

| Monocytes | TSP1 | Superoxideb | Cytochrome c | (225, 277) |

| Macrophages | TSP1 | Superoxideb | Luminol | (154) |

| Macrophages | IgV domain of CD47 | ROS | Nitroblue tetrazolium assay | (5) |

| Macrophages | SIRP-α-target SHP2 | ROS | Luminol | (136) |

| Pulmonary endothelial cells | TSP1 (hypoxia induced) | Superoxidec | Dihydroethidium fluorescence | (11) |

| Arterial VSMCs | TSP1 | Superoxide | Cytochrome c | (36) |

| Aortic rings | TSP1 | Superoxide | Electron paramagnetic resonance | (36) |

| Arterial VSMCs | CD47 WT vs. null cells | Superoxidec | Mitosox | (56) |

| Aortic rings | TSP1 | ROS | Tempol | (11) |

| Coronary arterioles | TSP1 | Superoxidec | Dihydroethidium fluorescence | (182) |

| Liver | CD47 | Superoxidec | Dihydroethidium fluorescence | (303, 304) |

| Fibroblasts | CCN1 | ROS | DCFDA fluorescence | (101) |

| Fibroblasts | CCN2 | ROS | DCFDA fluorescence | (101) |

| Hepatocytes | CCN1 | ROS | Dihydrocalcein-AM fluorescence | (27) |

| Myofibroblasts | CCN1 | ROS | DCFDA fluorescence | (15) |

| Endothelial cells | Periostin | No ROS | DCFDA fluorescence | (316) |

ROS indicates general detection of oxidants. Although authors often presume detection of specific oxidant species, most fluorescent dyes or other assays are not specific for detecting superoxide. Intracellular DCFDA fluorescence produced by intracellular oxidation of 5/6-chloromethyl-2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate and related derivatives is not specific for superoxide.

Extracellular superoxide confirmed by loss of signal after SOD treatment.

Dihydroethidium and Mitosox are selectively oxidized by superoxide to yield red fluorescent 2-OH-ethidium+. However, in the absence of supporting chemical characterization of the fluorescent product, other oxidants including OH• and HOCl can generate similar fluorescent products and can indicate activation of myeloperoxidases rather than NADPH oxidases (150).

DCFDA, 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells; WT, wild type.

Leukocyte adhesion deficiency is caused by defective β2 integrin function, suggesting that TSP1 may regulate PMN superoxide production through integrin signaling. However, another study localized the adhesion activity of TSP1 for PMNs to its 140 kDa C-terminal region and provided evidence that this was not mediated by a β2 integrin or the known RGD integrin binding site in this region of TSP1 (258). Although these earlier studies established that TSP1 has a supportive role to stimulate production of ROS by PMN, a direct role for TSP1 in this process remained unclear.

2. Roles of TSP1 receptors

Several studies have examined a potential role of the TSP1 receptor CD36 in regulating ROS production by monocytes. Antibody cross-linking of CD36 on human mononuclear cells induced a strong oxidative burst, characterized by measurement of SOD-inhibitable cytochrome C reduction (277) and by chemiluminescence (225). Treatment of these cells with TSP1 alone did not induce an oxidative response, but cross-linking TSP1 bound to the surface, or two treatments with TSP1 (225), enhanced oxidative burst in a CD36-independent manner (225).

More recent studies suggest indirect mechanisms by which TSP1 signaling through CD36 can regulate oxidative inflammatory responses in macrophages. One mechanism involves TSP1 induction of toll-like receptor 4 expression on macrophages (137). TLR4-deficient macrophages did not respond to TSP1, and activation was partially inhibited by a peptide or antibody that blocks binding of TSP1 to CD36. In another study, a recombinant TSR domain of TSP1 that contains its CD36 binding site enhanced the inflammasome-dependent maturation of IL-1β in human THP-1 monocyte-derived macrophages (254). ROS production is an effector pathway induced by inflammasome activation (1), suggesting that TSP1 signaling through CD36 could increase ROS production by this mechanism.

In contrast to these proinflammatory effects of TSP1 signaling through CD36, the resolution of LPS-induced lung injury was found to be delayed in Thbs1−/− mice, which was associated with defective macrophage production of IL-10 (314). Administration of recombinant IL-10 to the Thbs1−/− mice corrected this defect in vivo. IL-10 production by Thbs1−/− macrophages in vitro could be restored by a recombinant TSP1 TSR construct, and siRNA knockdown of CD36 in macrophages inhibited IL-10 production, confirming an inhibitory role for TSP1-CD36 signaling in macrophage inflammatory responses. TSP1 signaling via CD47 may also contribute to IL-10 regulation in macrophages because circulating IL-10 levels were elevated in Cd47−/− mice infected with Candida albicans (180), and TSP1 inhibited IL-10 expression in irradiated ANA-1 macrophages (204). TSP1 at 2.2 nM also inhibited IL-10 mRNA expression in Jurkat T cells but not in a CD47-deficient mutant, demonstrating that TSP1 signaling through CD47 can also regulate expression of this anti-inflammatory cytokine (204).

Further insights into TSP1 regulation of macrophage ROS signaling were obtained by investigating how TSP1 regulates macrophage killing of tumor cells (154). Treatment of interferon-γ-differentiated U937 cells, monocytes, and murine macrophages with TSP1 (∼10 nM) for 40–130 min (depending on cell type) augmented phorbol ester-mediated superoxide production as characterized by luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence, whereas treatment with exogenous SOD quenched the ROS signal (154).

A recombinant N-terminal domain of TSP1, but not the TSR or C-terminal domains, partially recapitulated the effect of TSP1 to increase phorbol ester-stimulated superoxide production. The N-terminal domain contains binding sites for several β1 integrins. A function-blocking antibody to integrin α6β1 and an α6β1-binding peptide derived from this domain of TSP1 partially suppressed the TSP1-induced production of superoxide by differentiated U937 cells. The ability of TSP1 to enhance ROS depended on intracellular Ca2+ and was inhibited in the presence of extracellular ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid. The cytotoxic activity of activated macrophages for tumor cells in these experiments depended on extracellular release of superoxide. TSP1 consequently enhanced the killing of target tumor cells by human and murine macrophages.

3. Role of CD47 counter-receptor SIRPα

Studies of signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) signaling in macrophages indicate that this counter-receptor for CD47 can regulate superoxide production in a cell autonomous manner, wherein CD47 serves as the ligand that activates SIRPα via cell–cell interactions (5, 136). One mechanism involves reverse CD47-SIRPα signaling (5). Binding of the IgV domain of CD47 to SIRPα on macrophages recruits Janus kinase (JAK) and induces its Tyr phosphorylation (Fig. 9). This results in JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-mediated induction of NOS2 expression, and the resulting released NO can react with superoxide to form the nitrosating species N2O3. In parallel, SIRPα ligation induces phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent Rac1 recruitment to Nox1, increasing superoxide production. A subsequent study reported that the phosphatase SHP2 stimulates ROS production, measured by enhanced luminol chemiluminescence ± diphenyleneiodonium chloride, by dephosphorylating SIRPα and activating ERK (136), which can activate Nox1 by phosphorylation of p47phox (152) (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

Model for TSP1 modulation of SIRPα-mediated ROS and NO production. Binding of CD47 to the extracellular V-domain of SIRPα induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain, which recruits the phosphatase SHP2. Binding of its counter-receptor also increases JAK2/STAT signaling to induce NOS2 expression and PI-3-kinase-dependent Rac1 recruitment to Nox1, which activates it to produce extracellular superoxide. Because TSP1 inhibits the interaction of the extracellular domain of SIRPα to CD47 in biochemical assays (84), TSP1 has the potential to inhibit these SIRPα signaling pathways independent of its CD47-mediated modulation of redox signaling. SIRPα, signal regulatory protein α. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Further studies are needed to determine whether this mechanism is also relevant in nonmyeloid cell types. In addition, given that TSP1 can inhibit binding of recombinant SIRPα to cell surface CD47 (84), the possibility should be considered that TSP1 can inhibit this signaling in cells that express SIRPα by preventing CD47 counter-receptor binding (Fig. 9).

B. TSP1 and ROS signaling in vascular and renal cells

Distinct from the innate immune function of extracellular ROS production by inflammatory cells, intracellular ROS production plays important roles in signal transduction through reversible oxidation of reactive thiols on signaling proteins, including tyrosine phosphatases (282). TSP1 expression and intracellular superoxide levels were increased in primary human pulmonary arterial endothelial cells exposed to short-term hypoxia (1% FiO2, 12 h) (11). Conversely, hypoxia-mediated increases in superoxide were abrogated by treating cells with a CD47 antibody (clone B6H12, 1 μg/ml) or with the NOS inhibitor L-NAME, suggesting that eNOS was the source of ROS under these conditions. Interestingly, siRNA suppression of caveolin-1 (Cav-1) restored hypoxia-mediated ROS levels in endothelial cells treated with a CD47 antibody, suggesting that TSP1-CD47 dysregulation of Cav-1 participated in ROS production by these cells (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

TSP1 via CD47 and SIRPα stimulates increased superoxide production. TSP1 (2.2 nM), a concentration found in human plasma in disease, interacts with cell receptors CD47 as well as SIRP-α to stimulate increased superoxide levels. The Nox assembly subunit p47phox is activated (phosphorylated) in cells treated with TSP1 concurrent with increased superoxide. Suppressing Nox1, or interfering with TSP1 interactions with CD47 and SIRP-α, abrogates TSP1-mediated increases in superoxide. In hypoxic endothelial cells TSP1 via CD47 dysregulates caveolin 1 (Cav-1) and eNOS, and is associated with increased superoxide. Superoxide may in a feedback manner interact with NO and sGC to limit NO signaling, and in a feed forward manner to possibly stimulate TSP1 expression. Together these pathways function to limit arterial vasodilation and impede blood flow. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Direct evidence that TSP1 treatment stimulates superoxide production was provided in human aortic VSMCs. Treating cells with 2.2 nM TSP1, which selectively engages CD47 but does not result in significant occupancy of other known TSP1 receptors, for 60 min resulted in a significant increase in superoxide (36) (Fig. 10). Interestingly, this effect was lost at TSP1 concentrations >11 nM, which are sufficient to activate TSP1 receptors other than CD47. Treatment with a CD47-suppressing morpholino oligonucleotide or a CD47 antibody (clone B6H12) blocked the TSP1-mediated increase in superoxide.

Treating cells with TSP1 resulted in increased phosphorylation of the Nox1 organizer subunit p47phox, whereas pharmacological inhibition of protein kinase C abrogated TSP1-stimulated increases in superoxide (36). A similar effect was found in arterial tissue. Treating endothelial-denuded murine aortic rings with 2.2 nM TSP1 for 60 min resulted in increased superoxide levels that were inhibitable by pretreating with a CD47 antibody (clone 301), as confirmed by electron paramagnetic resonance. Similarly, TSP1-mediated increases in superoxide were abated in VSMCs treated with NADPH oxidase 1 (Nox1) siRNA or in aortic rings from Nox1−/− mice but not in cells treated with control siRNA or in aortic rings from WT mice. In renal tubular epithelial cells, TSP1 also increased Nox1-derived superoxide levels and this involved interaction with SIRPα (307). Superoxide levels represent a balance between enzymatic production and catabolism by SOD. Interestingly, treating VSMCs with TSP1 (2.2 nM) for 1 and 2 h did not change SOD expression or activity (36). It remains to be determined whether TSP1-mediated increases in superoxide via SIRPα are independent of, or through, CD47 cross-talk.