Abstract

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a devastating, highly infectious illness with a high mortality rate. The disease is endemic to regions of Central and West Africa, where there is limited laboratory infrastructure and trained staff. The recent 2014 West African EVD outbreak has been unprecedented in case numbers and fatalities, and has proven that such regional outbreaks can become a potential threat to global public health, as it became the source for the subsequent transmission events in Spain and the USA. The urgent need for rapid and affordable means of detecting Ebola is crucial to control the spread of EVD and prevent devastating fatalities. Current diagnostic techniques include molecular diagnostics and other serological and antigen detection assays; which can be time-consuming, laboratory-based, often require trained personnel and specialized equipment. In this review, we discuss the various Ebola detection techniques currently in use, and highlight the potential future directions pertinent to the development and adoption of novel point-of-care diagnostic tools. Finally, a case is made for the need to develop novel microfluidic technologies and versatile rapid detection platforms for early detection of EVD.

Keywords: Ebola virus, diagnostics, polymerase chain reaction, microfluidics, immunoassay

Introduction

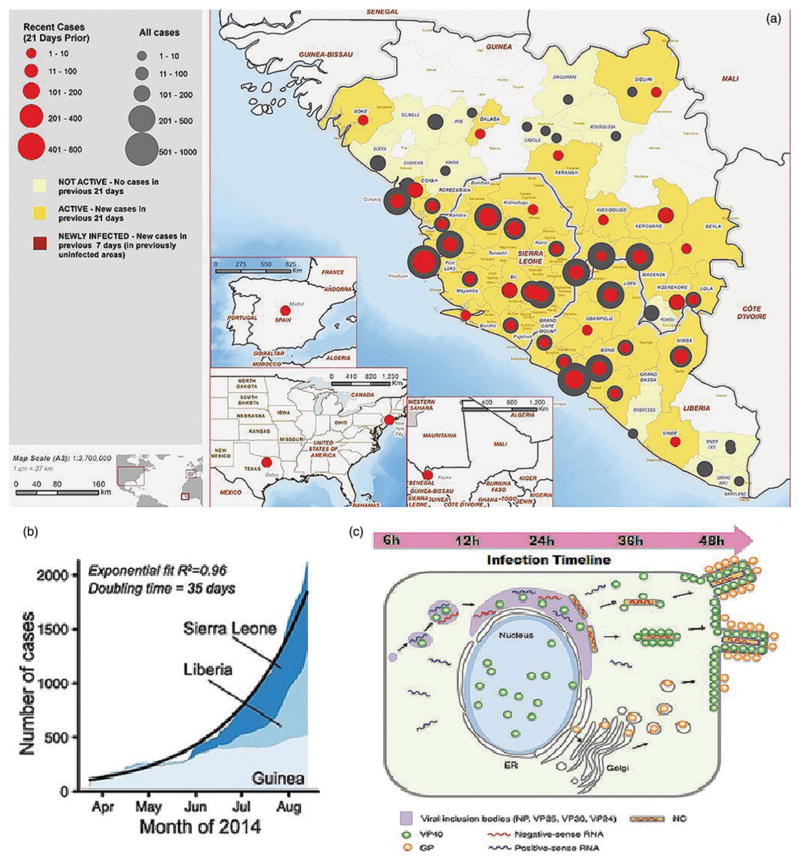

The current Ebola virus disease (EVD) crisis in West Africa is unprecedented. Initial outbreaks occurred in Guinea in late 2013 and rapidly spread to a total confirmed 28,610 cases and 11,308 reported fatalities. From 1976 to date, there have been a total of 24 known Ebola outbreaks within African countries. The unprecedented outbreaks in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and subsequent transmission events to Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Spain and the United States (Figure 1), represent a global concern. In the reported cases, EVD presents with fever (87.3%), fatigue (76.3%), vomiting (67.6%), diarrhoea (65.6%) and headache (53.4%) with an average case mortality approaching 70.8% (Aylward et al. 2014). The major causative agent, Zaire ebolavirus (EBOZ), is a negative-strand RNA enveloped virus from the Filoviridae family. Among the genus Ebolavirus (EBOV), there are also four other species that cause EVD: Sudan (SUDV), Bundibugyo (BDBV), Taï Forest (TAFV) and Reston (RESTV) (Kuhn et al. 2010). The latter, RESTV causes EVD restricted to Asian monkeys (Morikawa et al. 2007), although it has been shown to elicit an antibody response in humans (Miller 1990). The high infection rate, combined with a high mortality associated with EVD, requires strict biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory protocols while handling clinical samples for diagnosis. The 2014 outbreak called for alternative measures to cope with the overwhelming lack of healthcare infrastructure with sample inactivation occurring in contained Class III biological safety cabinets, “glove boxes”, or in on-site isolated hot laboratories (Flint et al. 2015). The virus presents a major public health risk and a significant potential for public panic and social disruption; prompting the US Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) to list EBOV as a Category A Bioterrorism Agent (CDC). Laboratory storage and specimen transport safety protocols of suspected virus-infected blood, serum, and tissue require that samples must be triple-packaged and stored at 2–8 °C. However, in the field, this may not be the case, as seen in the 2014 outbreak, samples that were transported sometimes wrapped in gloves were heavily clotted or potentially contaminated (Flint et al. 2015). Venous blood samples are taken consecutively for at least 3 d after patients show symptoms, and must be retested after 48 h to confirm EVD. In fact, retesting is necessary and multiple samples must be taken if symptomatic patients test negative. This is because the earliest window for viral genomic detection is roughly 48–72 h post-onset of symptoms, when the viral RNA is present (Figure 1(c)); while, serologic detection ranges from 8 to 16 d after symptoms present (Grolla et al. 2005; WHO 2014). The latent period of EVD varies among patients and typically ranges from 1 to 21 d, with an average 11.4 d during the 2014 outbreak. Following this latency, the incubation and onset of symptoms ensues rendering patients to be highly infectious, posing a greater risk of spreading the virus to others. This is quite problematic with current diagnostic methods heavily relying on clinical presentation and case history (Grolla et al. 2005), requiring patient travel to centralized testing centres, typically along with family, sometimes for hours. While awaiting diagnosis confirmation, the patients are collected into Ebola holding units (EHU), where potentially non-EVD patients can be exposed to EVD. This problem is potentially worsened because many clinical symptoms of EVD present similar a wide range of endemic diseases including Malaria, Typhoid Fever, Shigellosis and Cholera (Chua et al. 2015), which potentially can lead those clinically ill, non-EVD patients to the EHU. Furthermore, the centralized testing scheme exacerbates time spent for sample transport and processing which delays diagnosis, anywhere between 1 and 32 d (Chua et al. 2015), with a typical 5 d average (Dhillon et al. 2014). This critical delay in obtaining test results has placed the greatest health risk on patients and caregivers in the most recent outbreak (Perkins & Kessel 2015; Zachariah & Harries 2015).

Figure 1.

The current unprecedented and past EVD epidemiological outbreak maps and models; (a) image of the regions affected by the 2014 West African Ebola Outbreak (Aylward et al. 2014). Regional maps of confirmed and probable cases, clockwise from top right: (regions with declared epidemics) Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia; (regions with subsequent transmission events) Mali, Texas and New York in the USA and Spain. Reprinted with copyright permission from Aylward et al. (2014). (b) 2014 outbreak growth of confirmed, probable and suspected cases of EVD in each affected country under epidemic crisis (Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea). Reprinted with copyright permission from Gire et al. (2014). (c) Temporal sequence of Ebola infection within a 48-h duration in an infected cell, demonstrating the events prior to detectable threshold. Green and orange particles represent common serological targets, VP40 and GP, respectively. Viral RNA is represented by blue and red transcripts. Reprinted with copyright permission from Roca et al. (2015).

Following the initial months of the outbreak, the combined declining healthcare workforce and the lack of available local resources contributed to the rampant dissemination of the disease. The notion of exposure to the disease deters suspected patients from reporting to diagnostic centres for testing, consequently delaying diagnosis (Dhillon et al. 2014). Thus, the time variability for EVD diagnosis along with reluctance of suspected patients to report EHUs, hinders diagnosis; which is the sole control measure for preventing further EVD dissemination (Perkins & Kessel 2015; Zachariah & Harries 2015).

Current RT-PCR and other diagnostic assays require expensive equipment and trained personnel to handle samples, which prompted a major international response. Initially, the international community was only represented by the presence of two full functioning diagnostic labs in August 2014, 5 months into the outbreak. By October 2014, 12 diagnostic centres were established covering 80% of the districts. The response to contain the disease dramatically increased due to international attention, and by May 2015, 26 laboratories were established within Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia (Perkins & Kessel 2015). Through March 2015, on average 71% of samples were processed the same day as received, with the highest performed tests being 178 in a day (Flint et al. 2015). The key priority of stopping the spread of EVD is evident, and rapid diagnosis and control measures must be in place to curb any future outbreaks (Dhillon et al. 2014). This prompts the need for remote-area access to diagnostic testing to effectively identify and prevent the spread of EVD. Here, we review the current methods including nucleic acid and serological-based EVD detection and potential challenges faced. We review emerging techniques in microfluidics and nanotechnology that have shown promise in the future of biomedical engineering and conventional diagnostics. We have also highlighted the future directions to develop a reliable and efficient diagnostic platform for rapid EVD detection. These technologies propel clinical assessment with confirmatory diagnosis at the point-of-care (POC) for rapid diagnosis. Hence, the further drive to solve the current and future EVD outbreaks is sought through exploring cutting edge methods in creating early and rapid diagnostic devices at the POC with affordable costs (Chua et al. 2015; Dhillon et al. 2015).

Current genomic diagnostic methods for EVD detection

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for EVD detection

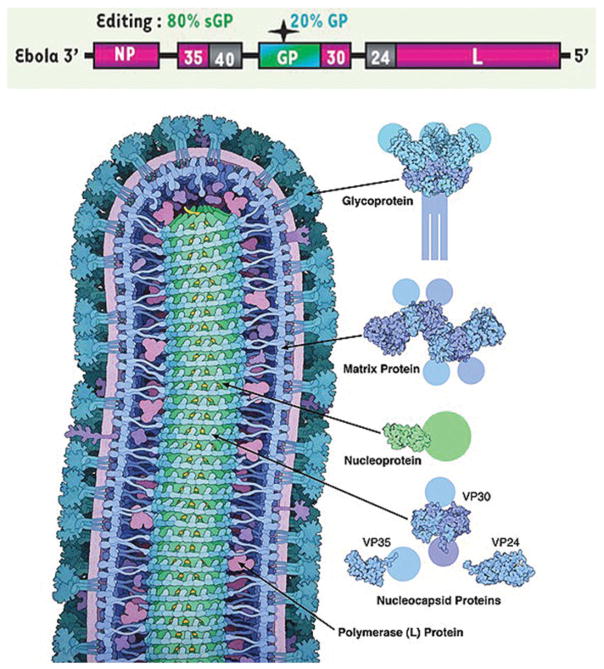

The viral genome of Ebola (Figure 2) is linear, and has been determined to be about 19,000 base pairs long, with seven coding regions for a nucleoprotein (NP), a polymerase cofactor (VP35), a matrix protein (VP40), a transmembrane glycoprotein (GP), a transcriptional activator (VP30), a viral envelope-associated protein (VP24) and a RNA–dependent RNA polymerase (L) (Sanchez et al. 1993; Nanbo et al. 2013). The GP gene also contains an open reading frame coding for a smaller, soluble GP (sGP), that has been detected in patient sera (Falzarano et al. 2006). The common genes targeted in genomic EBOV detection systems are shown in Table 1. The preferential genomic detection method is by Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) (Cherpillod et al. 2016). This protocol involves four steps, sample collection/inactivation, viral RNA extraction, reverse transcription and cDNA amplification. For RT-PCR diagnosis of EVD, RNA is extracted from whole blood and tissues ideally in a BSL-4 facility such as a reference or national laboratory, however, the CDC reported the use of a hot laboratory and separate clean laboratory for sample collection and RNA processing, respectively. In this method, the use of a hot laboratory eliminated the need for cumbersome “Glove Boxes” that require constant electrical supply to operate (Flint et al. 2015). RNA is tedious to work with and requires storage at −70 or −80 °C to prevent degradation. Sample contamination also risks a false-positive test result; thus, separation between the extraction and RT-PCR steps is critical (Drosten et al. 2002; Towner et al. 2004). During the 2014 outbreak, clean laboratories contained separate rooms for RNA extraction and genomic amplification (Flint et al. 2015), which was done to reduce any potential contamination. To inactivate the virus, decontamination protocols are followed typically by the addition of guanidinium thiocyanate buffers, which are commonly available within RT-PCR kits for RNA extraction purposes (Drosten et al. 2002; Weidmann et al. 2004; Towner et al. 2004, 2007; Grolla et al. 2005; Kurosaki et al. 2007; Le Roux et al. 2009; Pettitt et al. 2016). These are favourable and affordable solutions that neutralize viral sample, and have a shelf life of up to 2 months (Chomczynski 1994). This can be beneficial in remote areas, where shipping may not be as reliable.

Figure 2.

The Genomic and Protein maps of Ebolavirus (Alazard-Dany et al. 2006). (top) The overall ~19kbp genomic structure of Ebola with: a nucleoprotein (NP), a polymerase cofactor (VP35), a matrix protein (VP40), a transmembrane glycoprotein (GP), the GP gene also codes for an edited mRNA for a soluble glycoprotein (sGP), a transcriptional activator (VP30), a viral envelope-associated protein (VP24) and a RNA–dependent RNA polymerase (L). (b) A rendered Ebola virus protein schematic, displaying the viral proteins in their appropriate roles of the overall viral structure. Reprinted with copyright permission from Lee and Saphire (2009).

Table 1.

Survey of common genes targeted in genomic EBOV detection systems.

| Sample target | Number of assays using specific target | References |

|---|---|---|

| GP | 6 | Gibb et al. (2001), Günther et al. (2004), Rodriguez et al. (1999), Sanchez et al. (1999), Sanchez et al. (1996), and Trombley et al. (2010) |

| NP | 5 | Gibb et al. (2001), Huang et al. (2012), Towner et al. (2004), Trombley et al. (2010), and Weidmann et al. (2004) |

| VP40 | 1 | Trombley et al. (2010) |

| VP24 | 1 | Gibb et al. (2001) |

| L | 4 | Drosten et al. (2002), Gibb et al. (2001), Leroy, Baize, Lu, et al. 2000; Leroy, Baize,Volchkov, et al. 2000 |

PCR-based amplification requires thermal cycling among three different temperatures to denature cDNA, anneal primers to cDNA and amplify the cDNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. As RT-PCR protocol and associated procedures require electric power supply, a remote field laboratory can be furnished with a simple generator to overcome challenges of resource-constrained environment. Grolla et al. (2005) reported a PCR amplification run off a converted car battery source with a 700 W inverter for diagnosis. In fact, automated RT-PCR machines were employed in the 2014–2015 outbreak, employing both RNA extraction and RT-PCR in a single unit with an assay turnaround of 90 min; however, a constant power source was required, limiting the assay to regional laboratories during the outbreak (Broadhurst et al. 2016). Miniaturization of the thermo-cycler platform seeks to reduce diagnostic laboratory burden by reducing the volume of sample and reagents required, while increasing sensitivity and speed of the assay (Guo et al. 2012; Kiselinova et al. 2014), which could potentially allow for remote or isolated areas struck with EVD to receive faster turnaround. This thermal cycling is a limitation in designing Lab-on-a-Chip (LOC) POC devices for nucleic acid-based EVD diagnostics, and require intricate chip infrastructure and engineering to run the three distinct RT-PCR temperatures and establish reagent separation on a small scale for high-throughput capability. Recently, miniaturization of PCR has shown potential to overcome this limitation, resulting in the development of novel LOC microfluidic-based and droplet-based amplification technologies (Khandurina et al. 2000; Tewhey et al. 2009). However, further development of this and other similar diagnostic platforms must be conducted for high-throughput capability. One drawback to consider for RT-PCR is genetic drift associated with the imperfect nature of the Ebola RNA-dependent DNA polymerase (L). The enzyme has been known for its low fidelity. Further, Suzuki et al. have reported high mutation rates, with an average of 3.6 ×10−5 substitutions per site per year for the viral GP genes (Suzuki & Gojobori 1997). During the 2014 outbreak, Sabeti et al. used genomic surveillance to determine that the recent outbreak showed a mutation rate of 8 ×10−4 substitutions per site per year (Gire et al. 2014). These accumulated mutations alter sequences in the viral genome, and reduce specificity for RT-PCR primers. Thus, for every new outbreak, there is a potential for reduced sensitivity due to reduced primer recognition to the mutated viral genome. Thus, initial critical genome sequencing of suspected viral pathogens can be done to confirm efficacy of existing molecular diagnostic kits (Gire et al. 2014). An in silico model using the sequences of 2014 EVD patient samples compared against the current RT-PCR EVD assay kits in use found that the genomic shift influenced false-positive and false-negative results (Sozhamannan et al. 2015). Each assay performed differently in this model, but had similar results for primers made for the Makona (2014) and Kikwit (1995) EVD-causing strains. Hence, the developing a multitude of specific primers is an optimal approach for identifying the different species or strains of Ebola is crucial for improving the accuracy of diagnosis for new outbreaks.

Real-time (quantitative) RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) has been integral in several protocols and involves fluorogenic probes such as Taqman systems (Weidmann et al. 2004; Trombley et al. 2010; Huang et al. 2012; Pettitt et al. 2016) or less expensive intercalating fluorophores like SYBR green 1 (Saijo et al. 2006). The Taqman System uses a piece of cDNA with a reporter and quencher dye, and allows for direct quantitation of viral RNA (Heid et al. 1996; Pfaffl 2001). Depending on the reverse transcriptase enzyme being utilized in the RT-qPCR, it may possess a variable specificity to different segments of viral RNA. This variable specificity by reverse transcript-ase enzymes to viral RNA can potentially result in synthesis of varying levels of cDNA (Levesque-Sergerie et al. 2007), and can be especially problematic, if RT-PCR is for quantitative purposes. In order to have a sound diagnostic assay, reproducibility and specificity should be validated. Currently, RT-qPCR is used as the standard to quantify viral infections in clinical settings, and was adopted by a wide range of assays used in the 2014–2015 Outbreak.

One-step and two-step RT-PCR

The current gold standard for EVD diagnosis used RT-PCR technique follows one-step and two-step RT-PCR protocols, and varying amplification methods and chemistry. In addition, the flexibility in protocol results in several benefits and disadvantages depending on field situation (Grolla et al. 2005; Towner et al. 2004).

During the two-step process, first a reverse transcriptase enzyme and complementary primers are added to the purified viral RNA extract in a buffer solution. This produces a cDNA after carrying out the reverse transcription reaction cycles. Then, in a separate tube, a polymerase chain reaction is prepared by adding the cDNA, along with forward and reverse primers and a thermostable DNA polymerase, which is then subjected to amplification reaction cycles (Towner et al. 2004; Grolla et al. 2005). One major advantage to the two-step method is that the entire viral genome can be copied to cDNA in a controlled setting, and then in the PCR step, the number of viral copies can be accurately quantified in infected patients using a fluorogenic dye. Towner et al. (2004) utilized the Taqman system for cDNA quantification as a potential patient outcome predictor. By quantifying the RNA transcript titre from cDNA amplification, it was found that patients who survived had a titre less than 108 RNA copies/ml. However, it should be noted that the disadvantage of this two-step method is that it requires the transfer of the newly synthesized cDNA extract into a new tube for the PCR reaction, thereby requiring additional time to prepare and load the PCR reagents. It was reported during the 2014 outbreak, using RT-PCR allowed on average 63 samples tested a day (Flint et al. 2015), equating to only almost 2.3% samples processed a day on average, out of the 28,610 confirmed cases. If the throughput of this assay could be increased, potentially many more patient samples could be processed daily. Also, potential contamination, degradation of sample or denaturation of cDNA during sample handling and manipulation could lead to a false-negative result. Thus, laboratory personnel must be trained to handle samples to ensure accurate results.

In a one-step RT-qPCR, the protocol is modulated to perform a reverse transcription as well as cDNA amplification in a single step. A reverse transcriptase enzyme along with a DNA polymerase is mixed with a fluorogenic dye. Reaction cycles occur for the reverse transcription and cDNA amplification respectively (Drosten et al. 2002; Towner et al. 2004; Weidmann et al. 2004; Saijo et al. 2006). The advantage of this method is that it prevents possible contamination by combining both reverse transcription and PCR amplifications; herein, eliminating the need to run a separate PCR amplification step. By combining both steps, this RT-PCR reaction reduces processing time; which can allow for a more diagnostic turnaround. The single step RT-qPCR technique also has high sensitivity to the viral RNA, with a forward and reverse primer scheme that detects at a threshold of 103 RNA copies/ml (Towner et al. 2004). This could be useful for an earlier window of diagnosis. However, a disadvantage of the one-step method is that inclusion of reverse transcription reaction with the cDNA amplification reaction results in a variation in the amount cDNA copied during reverse transcription. Unlike the two-step method, the lack of control of the reverse transcription reaction results in varying amounts of cDNA being copied and amplified, depending on the enzyme’s affinity (Levesque-Sergerie et al. 2007). This may limit the one-step method’s potential for quantitative purposes that require a constant level of synthesized cDNA. Despite this limitation, the onestep RT-PCR has shown to have high sensitivity in the detection of EBOV compared with other diagnostic techniques, and can potentially be utilized for highly sensitive early diagnostic purposes. Table 2 lists the relevant molecular diagnostic tests that were deployed during the recent 2014–2015 outbreak, which shows that the one-step RT-PCR method was predominant in clinical settings.

Table 2.

A survey of RT-PCR platforms in development used during the 2014–2015 outbreak (Perkins & Kessel 2015).

| Source | Assay name | Platform rype |

|---|---|---|

| Altona Diagnostics | Ebolavirus RT-PCR Kit 1.0a | One step |

| Roche | LightMix Modular Ebola Virus Zairea | One step |

| Shanghai ZJ Bio-Tech | Ebola Virus (EBOV) Real Time RT-PCR Kitb | One step |

| US Centers for Disease Control | CDC Ebola Virus NP Real-time RT-PCR Assaya | One step |

| US Centers for Disease Control | CDC Ebola Virus VP40 Real-time RT-PCR Assaya | One step |

| US Department of Defense | DoD EZ1 Real-time RT-PCR Assaya | One step |

US FDA Emergency Use Authorization.

European Conformity Mark for in vitro diagnostic.

Nested RT-PCR

Nested RT-PCR is an offshoot technology from PCR that utilizes highly accurate and specific techniques involving two primer sets that amplify precisely exact regions of viral RNA. In this method, by using two sets of primers, a specific region of cDNA is amplified from a larger RNA segment. First, a primer designated for outside flanking regions of the viral RNA target binds and is amplified in a one-step RT-PCR reaction, which results in the amplified target product with extraneous flanking trailer regions. The second primer binds specifically to the target cDNA promotor, resulting in only target sequence amplification in the second round of PCR, which creates a highly amplified target product which can achieve detection even with small concentrations of genomic material, and increases the test sensitivity. Nested RT-PCR has been used to target the conserved EBOV NP genes successfully (Towner et al. 2004). The advantage to nested RT-PCR is the specificity of target site that is being amplified, resulting in a mass amplification of only the specific viral target sequence. This process overall reduces the amount of non-specific primer binding, which improves test accuracy. The disadvantage to the nested RT-PCR is the risk of contamination by having the additional step of adding the second primer set, which can produce a false-positive and can risk lab contamination from exposure (Drosten et al. 2002). The nested reaction is an accurate means of amplification by reduction of non-specific primer binding, and can be used as an accurate means of quantitation (Porter-Jordan et al. 1990). Thus, for early detection, either a one-step or nested RT-PCR may be considered, but to reduce the assay time and technical burden, a one-step method maybe preferable.

Reverse transcription-loop mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP)

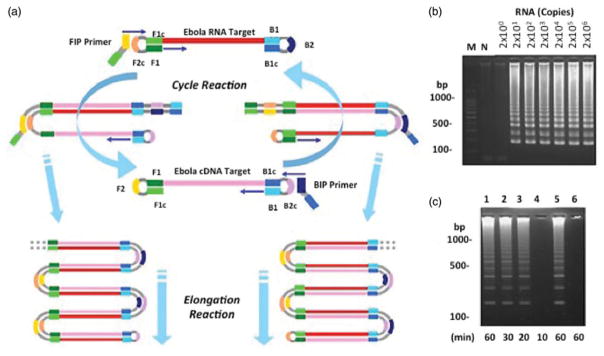

During the last decade, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) has emerged as an efficient and rapid means of genomic diagnostics in infectious diseases (Safavieh et al. 2016). Similar to a one-step RT-PCR, the RT-LAMP assay is conducted as a one step, in which initial reverse transcription of the target RNA into cDNA is performed prior to the PCR amplification. The reaction proceeds at 63 °C using a bst1 polymerase (Safavieh et al. 2017) with a set of four DNA primers (Kurosaki et al. 2007) (Figure 3). The inner primer BIP (B2, B1c), a software-generated primer designed with homology to regions of the target viral RNA genes, binds to RNA with B1c as a hanging fragment. The B1c fragment is also the exact sequence of a region near the target RNA and adjacent to the B2 binding site (B2c). Then an outer primer (B3) binds and displaces the newly formed cDNA, as a DNA polymerase copies a new cDNA strand. The displaced cDNA strand contains the complimentary sequences with the hanging B1c, and both bind together to form a loop-end (Mori & Notomi 2009). The reaction continues in an opposite direction with another set of inner primers, FIP (F2, F1c). These bind to the displaced cDNA at the binding site (F2c), and DNA polymerase copies a DNA copy of the RNA template. As with the outer B3 primer, another outer primer, F3 binds to the F3c segment, and a DNA polymerase copies a new strand, displacing cDNA from the RNA strand. Once the cDNA has been copied, the amplification can proceed. Using the same methodology of overlapping complementary fragments and annealing, the amplification continues to create long chains of hairpin DNA (Mori & Notomi 2009). RT-LAMP shows great promise for disease detection at remote or resource-limited areas because RT-LAMP reaction occurs at constant temperature conditions (Safavieh et al. 2017), which differs from normal PCR amplification reaction cycles that uses multiple temperature fluctuations. Online databases provide a catalog of primers, which facilitates the process of primer selection and design. All LAMP reagents can be stored in powder form in refrigeration-free conditions, and can be reconstituted for use at the point of need. Kurosaki et al. (2007) have developed and tested RT-LAMP designed and tested for the Ebola viral genome, using a green fluorescent protein-tag that could amplify as few as 20 copies of viral RNA in vitro, and could also amplify viral gene products from as few as 1 ×10−3 FFU (Kurosaki et al. 2007). Thus, this novel technology is a promising LOC diagnostic method as it can be miniaturized and applied to real world scenarios due to its isothermal requirements. In fact, at least one LAMP-based diagnostic assay was being developed for the 2014 EVD outbreak (Whitehouse et al. 2015). With already showing high sensitivity in vitro for Ebola detection, potential remote field capability, and integration with micro- or nanoscale technologies make RT-LAMP a potential next-generation genomic diagnostic tool for EVD. Despite the usefulness of the RT-LAMP assay, no platform has been clinically validated for diagnostic use in outbreak conditions, and future work should be done to verify RT-LAMP as a sensitive assay for EVD in clinical settings.

Figure 3.

RT-LAMP final cyclic reaction and elongation steps; (a) following the FIP primer binding, there is another round of polymerization. A reverse transcriptase binds the FIP primer making a cDNA copy. This step is continued with the BIP primer, which makes a template DNA strand from cDNA polymerization. The outside reaction is repeated in multiple rounds, allowing for mass amplification of the Ebola RNA target. Reprinted with copyright permission from Notomi et al. (2000). (b) Results of RT-LAMP for Ebola (Kurosaki et al. 2007) showing sensitivity of the amplified in vitro Ebola RNA at only 20 copies. (c) The duration of the Ebola genome amplification by RT-LAMP have shown to detect Ebola within 20 min. Reprinted with copyright permission from Kurosaki et al. (2007).

Current serological diagnostic methods for EVD detection

The earliest appearance of viral antigen is about 3–6 d post-onset of symptoms, and titre has shown to decrease and disappear within 7–16 d after disease onset (Rowe et al. 1999). Serological techniques developed for the detection of EBOV have been a key indicator of infection, and has been a critical diagnostic tool for outbreaks and epidemics (Ksiazek, Rollin, et al. 1999). The use of serological diagnosis provides an accurate and rapid means of detection, and can be used directly with tissue or patient blood samples. Patient samples are tested either by quantification of viral particles or by measuring the patient’s immune response titre (Grolla et al. 2005). Various antigens and antibodies are used in EBOV detection assays as shown in Table 3. The discovery of new anti-Ebola antibodies from patient plasma serum or from synthetic monoclonal antibodies has provided a sensitive means of virus detection. Further means of mapping the viral epitope of anti-Ebola antibodies (Niikura et al. 2001, Shahhosseini et al. 2007), analyzing temporal distribution of viral antigen expression (Ksiazek, Rollin, et al. 1999; Nanbo et al. 2013) and the demonstration of cross reactivity between human anti-Ebola antibodies, show promise in the development of rapid and sensitive serological devices for POC EVD detection. Current diagnostic protocol recommends RT-PCR as the predominant diagnostic method for EVD (Towner et al. 2004; Grolla et al. 2005; Feldmann & Geisbert 2011; Gire et al. 2014; Cherpillod et al. 2016); however, there should be a push to develop more diverse serological diagnostic systems, with their portability and reliability in use as portal assays for EVD (Chua et al. 2015).

Table 3.

Antigen and antibodies used in EBOV detection systems.

| Sample target | Number in system implementation | References |

|---|---|---|

| GP | 5a | Kallstrom et al. (2005), Kamata et al. (2014), Lucht et al. (2004), Nakayama et al. (2010), and Shahhosseini et al. (2007) |

| NP | 2 | Ikegami et al. (2003), Kamata et al. (2014) |

| VP30 | 1 | Lucht et al. (2003) |

| VP40 | 5 | Kallstrom et al. (2005), Kamata et al. (2014), Lucht et al. (2003, 2007), and Shahhosseini et al. (2007) |

| Whole Serum | 2 | Ksiazek, West et al. (1999) and Zaki et al. (1999) |

| IgM Anti-Ebola Antibodies | 2 | Ksiazek, West et al. (1999) and Zaki et al. (1999) |

| IgG Anti-Ebola Antibodies | 2 | Ksiazek, West et al. (1999) and Zaki et al. (1999) |

Including sGP antigen.

Antigen detection methods

The standard early diagnostic protocol for antigen detection in patient serum is the an antigen-capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) (CDC), or referred to as “sandwich” ELISA. In this assay, a well is coated with an antibody against the select viral antigen. Initially, a well is rinsed with 5% milk/PBS to prevent non-specific binding sites of the antibodies (Kallstrom et al. 2005), which reduces false-positive results. After the infected serum or tissue sample is processed, it is loaded into the well, and incubated to allow optimal antibody–epitope binding. Then the unbound, excess sample is removed by a subsequent rinse step. Another antibody directed against the target antigen added to the well and incubated, thus completing the “sandwich”. After the “sandwich” is formed, an indicator antibody specific to the previous antibody is added to the well and incubated. This antibody is conjugated with an enzymatic indicator with specificity to a fluorogenic or dye reporter substrate, and binds to the “sandwich” antibody complex. After a final rinse, the colorogenic substrate is added to the well, and the visually reactive results indicate a positive test. The antigen capture systems are extremely pertinent in early stage diagnosis of EVD infection; however, typically give results 48–72 h after diagnosis can be made by RT-PCR (Towner et al. 2004). Thus, RT-PCR is more effective as a diagnostic test, able to identify cases sooner than standard ELISA-based serological tests. Despite this, antigen capture assays are also useful for early EVD detection due to the simplicity of ELISA protocols compared with RT-PCR. Towner et al. (2004) demonstrated that antigen titre is the highest between 2 and 8 d post-onset of illness in both fatal and non-fatal outcomes. Thus, antigen detection of EVD holds potential for rapid and early POC diagnostic development. However, biohazard limitations on antigen collection hinder the ability to verify and validate typical antigen detection methods, and must be performed typically at reference and national laboratories; which is not ideal in resource-limited conditions.

Various other antigen detection methods have also been evaluated for confirmatory diagnosis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF). Immunohistochemical assays (Zaki et al. 1999) have been developed that can offer rapid and simplistic diagnostic tests. A novel immunofiltration test for EBOZ developed by Lucht et al. (2007) was able to detect the viral infection rapidly (within 30 min) without the requirement of electric supply at a similar sensitivity of ELISA. These lateral flow assays can be leveraged with metallization reactions to enhance sensitivity as higher sensitivity has been reported using silver nanoparticles for EVD detection (Yen et al. 2015). Table 4 documents the current antigen detection lateral flow assay platforms in development for POC diagnosis for EVD. These assays can be performed with microlitre sample volumes, and give rapid assay turnaround times. Such rapid and straightforward techniques are optimal for field diagnosis of EHF at POC settings. The Fluorescent Antibody Techniques (FAT) have also been useful in previous EVD outbreaks (Bouree & Bergmann 1983; Ksiazek, Rollin, et al. 1999; Ksiazek, West, et al. 1999; Nanbo et al. 2013). These methods are useful in epidemiological studies in reference or national laboratories, and have potential use to survey and prevent EVD outbreaks (Zaki et al. 1999). However, the sensitivity and procedural technicality of FAT may not compare favourably with today’s standards such as ELISA (Ksiazek, West, et al. 1999). Finally, an emerging field of serological EVD detection, lateral flow immunoassays (Broadhurst et al. 2015; Perkins & Kessel 2015) can offer the opportunity to miniaturize current ELISA and other immunoassays for potential portability, automation and reliability. With these constraints, a highly sensitive assay can be developed. For example, the ReEBOV Antigen Rapid Kit by Corgenix had a sensitivity of 100% and 95% specificity when compared with conventional RT-PCR for EVD (Broadhurst et al. 2015) in a limited amount of patients during the 2014–2015 outbreak. Thus, these antigen detection platforms possess significant potential for the development of future EVD POC diagnostics, but must have further validation for clinical diagnosis in outbreak settings (Broadhurst et al. 2016).

Table 4.

Current rapid antigen detection lateral flow assays in development for EVD (Perkins & Kessel 2015)*.

| Company | Assay name | Required sample collection |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative and Atomic Energy Commission (Paris, France) | Ebola eZYSCREEN | Fingerprick/Capillary Blood Sample |

| Chembio Diagnostics (Medford, MA, USA) | Ebola Antigen Detection | Fingerprick/Capillary Blood Sample |

| Corgenix (Denver, CO) | ReEBOV Antigen Rapid Test | Fingerprick/Capillary Blood Sample |

| OraSure (Bethlehem, PA) | – | Fingerstick or Venous Blood Sample |

| SD Biosensor (Seoul, South Korea) | SD Q Line Ebola Zaire Ag | Fingerprick/Capillary Blood Sample or Patient Sera |

| Senova (Jena, Germany) | DEDIATEST-Ebola | Patient Sera or Throat Swab |

All are at least World Health Organization Prequalification status.

Anti-Ebola antibody detection

The detection of anti-Ebola antibodies through IgM/IgG ELISA is another effective diagnostic tool (Ksiazek, West, et al. 1999; Nakayama et al. 2010). In the early stages of infection, the body produces an IgM response; however, anti-Ebola IgM antibodies are rapidly degenerated at the earliest 30 d post-onset of infection (Ksiazek, Rollin, et al. 1999; Ksiazek, West, et al. 1999). IgM antibodies are present earliest 6 d post-onset of symptoms with IgG titres develop 6–18 d post-onset of symptoms, respectively (Grolla et al. 2005). Despite this variability, IgM is typically not present in non-fatal EVD cases after 80 d post-onset of symptoms (Broadhurst et al. 2016). Furthermore, people with EVD that do not survive, often die before mounting a proper humoural immune response. This suggests that antibody-based detection systems for Ebola may not be as useful as antigen-based or viral isolation methods (Grolla et al. 2005). Since IgG antibodies develop days after disease onset, anti-Ebola virus IgG antibody detection may not be useful as an early diagnostic tool, and may suggest to serve as an epidemiological surveillance marker. Retesting is encouraged for serum samples, because rising IgG and falling IgM titres suggest Ebola diagnosis (Grolla et al. 2005). These antibody capture systems utilize a similar protocol as used for antigen capture ELISA; however, a purified viral antigen is placed into wells to capture and detect antibodies. An IgM ELISA system developed by Ksiazek et al. was shown to detect anti-Ebola IgM antibodies reliably within 10 d post-infection (Ksiazek, West, et al. 1999). However, this method showed specificity to RESTV, but not to EBOZ or SUDV species. These results show the disadvantages of antibody-based detection, because not all the anti-Ebola antibodies confer the same epitope conformation to the capture antigen. Furthermore, Ksiazek, Rollin, et al. 1999; Ksiazek, West, et al. 1999 found that antigen detection is the predominant means of ELISA-based Ebola detection compared with antibody detection in terms of sensitivity and time. The subtle differences in species-specific viral antigen prevent recognition by target antibodies, and pose a limitation in designing an antibody-based detection system capable of capturing different species and strains of the Ebola.

Monoclonal antibody development

Most recently with the advances of recombinant DNA technology, monoclonal antibodies have been synthesized in vitro against Ebola viral antigens and anti-Ebola antibodies (Prehaud et al. 1998; Niikura et al. 2001; Ikegami et al. 2003; Lucht et al. 2003, 2004; Nakayama et al. 2010; Saijo et al. 2006). These antibodies are specifically directed against various viral epitopes, and are an integral part in cutting edge Ebola diagnostics. With the developments of synthetic biology, several experiments have been performed using recombinant proteins of the Ebola virus, and have produced antibodies that are directed against viral antigens (Prehaud et al. 1998; Saijo et al. 2006).

Lucht et al. (2003) describe a monoclonal antibody system against the VP40 protein with at least six out of nine different monoclonal subclasses reacting with four different EBOV species, EBOZ, SUDV, TAFV and RESTV. In another experiment, they also demonstrated a successful ELISA system with sensitivity up to 1:2000 serum titre for the detection of the envelope GP (Lucht et al. 2004). Saijo et al. (2006) also found that viral antigens were detected by recombinant protein-based systems, these antibodies even cross-reacted with other EBOV species. Changula et al. (2013) developed anti-Ebola monoclonal antibodies against species-specific NP, and mapped out epitopes to generate three antibodies with cross-reactivity. These studies further facilitate the development of an array of antibodies, and show the necessity of mapping epitopes as a means of implementing systems capable of broad recognition of EBOV antigens. Another monoclonal antibody system developed by Nakayama et al. (2010) showed low cross-reactivity to heterologous antibodies directed against species-specific GP by ELISA, which could be developed into a species-specific antibody test. The use of multiple sets of monoclonal antibodies instead of one further enhances the ability to rapidly diagnose EVD. Shahhosseini et al. (2007) produced different monoclonal antibodies directed against Ebola virus-like-particles and a fragment of the GP, and was able to determine two antibodies suitable for early detection. Monoclonal antibody development for Ebola antigens has led to both potential species-specific and conserved epitopes which hold potential use for diagnostic platforms for EVD detection. Despite this, assays using antibodies raised against recombinant Ebola virus antigens have not been validated for clinical diagnosis of EVD.

Studies of the binding of antibodies to EBOV antigens have been done to elucidate their binding conformation and epitopes that confer potential activity to neutralize or give immunological protection. Structural studies of the GP were shown to contain a trimeric mucin-like domain, nearly half the density of the entire protein, that may be a key to understanding the immune evasion through conformational modification after viral entry (Lee et al. 2008; Lee & Saphire 2009). Such structural studies can offer an immense contribution to optimal antibody selection for diagnostic device, by understanding the biochemical complexities of the viral proteins, and elucidating the most successful anti-Ebola antibodies. Further technologies should implement epitope mapping as a standard, to find and develop the most efficient monoclonal antibody-derived rapid detection systems.

Development of potential alternative and future biosensors using nanotechnology and microfluidics for LOC EVD diagnosis

With the discoveries of advanced biosensor technologies (Hirsch et al. 2003; Cooper & Singleton 2007; Chambers et al. 2008; Wang 2011; Asghar, Ilyas, Billo, et al. 2011; Asghar, Ilyas, Deshmukh, et al. 2011, 2012; Wan et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013), applications exploiting physical and electrochemical properties on micro and nanoscale have endless potential in the future of POC biosensors for early and rapid diagnostics. Biosensors consist of a particular recognition element specific for each sample and an interface for signal transduction to amplify a signal response (Chambers et al. 2008). Rollins et al. developed paper-based assay utilizing a biosensor with synthetic gene circuits that has been developed for species-specific EBOV detection of twelve 36 bp regions of NP mRNA transcripts. The sensor can be fabricated at 65¢ per test, and can detect as little as 30 nM of cell-free EBOV extract, and uses a functional lacZ gene to increase sensitivity of the system (Pardee et al. 2014). The push for novel biosensor technologies has resulted in the creation of inexpensive rapid detection devices for EVD. Thus, the area of novel biosensors show promise in the future of clinical EVD diagnostics at the POC level. Through this leveraging of miniaturization, biosignal process and amplification, novel technologies have emerged leading to potentially new diagnostic POC methods for EVD. During 2015, there were 13 molecular (genomic) diagnostic assays in various stages of development, and out of that only four were completely automated (Perkins & Kessel 2015). Similarly, there were at least seven lateral flow antigen detection assays under development, which have the potential for POC capability, but may be limited in sensitivity (Perkins & Kessel 2015). Several advantages arise from the integration of multiple processes on-a-chip, and show greater potential for development of rapid and reliable diagnostic platforms. The case for decentralized POC testing has been assessed as a result of the recent outbreak (Chua et al. 2015). Such devices should focus on the decentralized scheme that is advantageous for laboratory constrained or remote regions, which potentially eliminates the need for sample transport and delayed testing. A desirable EVD diagnosis platform should be done in a three-step or less assay that can be either qualitative or quantitative with an acceptable clinical sensitivity greater than 95% within the first 10 d of clinical presentation. Miniaturized LOC diagnostic methods ensure that significantly smaller sample volumes can be utilized, reduce the amount of time to process and analyze sample and have the potential to be fully automated. This is advantageous in terms of throughput, as it is recommended to have a desired assay run time of under 30 min (Chua et al. 2015). With the immense potential for danger, biosafety must also be considered, thus it is still essential to perform these assays with typical PPE (Chua et al. 2015; Perkins & Kessel 2015). Thus, validation, even with stringent in vitro testing of diagnostic LOC assays, may be difficult, due to limited access and potentially hazardous exposure while working with the virus in vitro or in the field; which would require biosafety PPE (Chua et al. 2015). Despite this, emergency authorization was granted in the 2014 outbreak by the FDA for Ebola diagnostic devices (Whitehouse et al. 2015), which prompted the need for development of international protocols for humanitarian, interventional use of unapproved medical devices that show promise for deployable, rapid POC diagnostics (Singh 2015). Other methods such as paper-based microfluidics should also be considered in the development for high-throughput diagnostics (Shafiee et al. 2015b). Some recent breakthroughs in paper-based microfluidics have been shown to allow longer shelf life of these potential diagnostics that can be stored for at least 6 months at room temperature (Asghar et al. 2016). Such affordable technologies can potentially lessen the logistic and financial strain as seen from the overwhelming spread of EVD during the 2014–2015 outbreak (Bausch & Schwarz 2014; Kalra et al. 2014). Another potential advantage to development of LOC devices is the ability to real-time interface with a data pooling system. In this way, the spread of EVD could be tracked. Such a powerful epidemiological tool has potential to help contain the spread of the virus (Tambo et al. 2014), further preventing loss of life and thereby reducing the negative socioeconomic impact in affected regions, using decentralized testing. Thus, the development of portable and rapid EVD detection methods using alternative technologies show promise as the tool in forefront of EVD diagnosis for containment and control of future EVD outbreaks. This shift to decentralized-favoured testing is critical to the control of the spread of the disease in the regions where the most recent outbreak occurred; however, this also equally can pose a challenge to assay validation in clinical settings. In future clinical testing, stringent protocols for development and testing for these novel methods for detections should be in place for validation of these POC platforms.

Magnetic particle-based biosensors

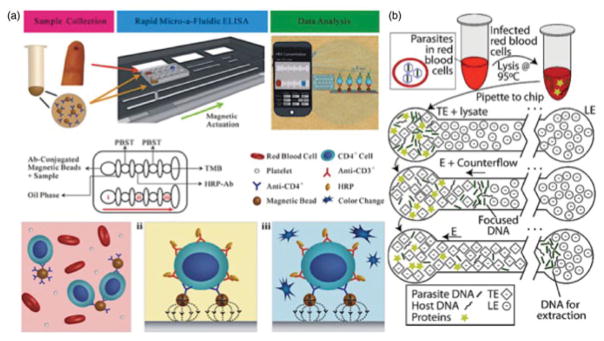

The development of magnetic particles functionalized with antibodies have been leveraged into automated detection platforms (Bhalla et al. 2013; Lien et al. 2011; Yun et al. 2007). Through automation, standard tests can be rendered hands-free, and using microfluidic platforms less sample or reagents are consumed. Recently, an ELISA was developed into a POC platform (Figure 4(a)), actuated with magnetic beads functionalized with anti-CD4 antibodies showing great potential for the rapid detection of HIV (Wang et al. 2014). Another magnetic-bead-based method has been used for isolation of SLE anti-DNA antibodies (Cavallo et al. 2012; Pavlovic et al. 2007). An on-chip DNA binding assay using biotin–streptavidin functionalized magnetic beads was developed to manipulate captured EBOZ RNAs for staining, and was able to detect as few as 6.25 ×10 4 PFU/ml (Cai et al. 2014). Such technology shows the benefit of magnetic beads actuation for nucleic acid detection of Ebola. These reports demonstrate the wide versatility of magnetic bead actuation for diagnostic devices, and lead potential for device automation. Rapid diagnostic technologies are essential to quickly contain the spread of infectious diseases. Specific EBOV antigens could also be targeted with functionalized magnetic beads for a potential automated platform for use in resource-limited areas to limit the number of fatalities and negative socioeconomic impact caused by dissemination of EVD.

Figure 4.

Magnetic bead actuation on a chip and whole-blood sampling isotachophoresis; (a) Functionalized magnetic beads with anti-CD4-antibodies in an HIV ELISA detection assay. Magnetic beads bind and capture CD-4 cells, and are actuated to each reaction chamber when a magnetic field is applied a colour change indicates a seropositive reaction in the final well. Reprinted with copyright permission from Wang et al. (2014). (b) Complex isotachophoresis on-a-chip designed to capture and isolate parasite DNA from infected leukocytes, using electric fields to generate electrophoretic separation of ionic samples. Reprinted with copyright permission from Marshall et al. (2011).

Isotachophoresis for rapid isolation of nucleic acids

Nucleic acid extraction and purification are critical steps required for most of genomic diagnosis methods such as PCR, RT-PCR and LAMP. Extraction of nucleic acids is typically performed through a series of organic separations, and has limited applicability to POC testing until with the development of capillary electrophoresis (CE) techniques (Rossomando et al. 1994; Woolley et al. 1996). These techniques separate migrating samples by trapping them between a leading and trailing buffer in an electrophoretic interphase, while a constant electric field is applied to the channel. A modified CE-based method, isotachophoresis (ITP), is a simpler design (Figure 4(b)) relying on similar CE separation strategies (Persat et al. 2009; Young et al. 2010; Jung et al. 2011; Garcia-Schwarz et al. 2012). This versatile platform has been developed into a LOC, and has a wide range of nucleic acid separation for diagnostic applications such as RNA extraction from bacteria (Rogacs et al. 2012), DNA isolation for the Hepatitis B virus (Liu et al. 2006) and DNA extraction of the Malaria parasite, Plasmodium from infected erythrocytes (Marshall et al. 2011). Once isolated, the nucleic acid can also be amplified on-a-chip (Liu et al. 2006) using DNA amplification methods. Ostromohov et al. describe a device combining ITP to pre-concentrate a target sample for PNA probes on a chip for potential disease detection. The developed device has shown a sensitivity for concentrations as low as a 100 pM of sample DNA targets, and runs under 1 min (Ostromohov et al. 2015). With rapid device runtime, and the ability to leverage this innovative extraction method on chip with other downstream genomic applications, high-throughput nucleic acid testing for Ebola could be established with such novel microfluidic devices.

Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes

Over the past two decades, various PNA probes have been developed as useful tools for the enumeration and characterization of microbes in environmental biology and ecology (Esiobu et al. 2004). PNA probes offer a greater accuracy compared to DNA-based oligonucleotide probe systems (Li et al. 2008). The PNA probes utilize a polyamide backbone that mimics DNA’s pentose-phosphodiester backbone, and even show superior binding to target DNA or RNA compared with traditional nucleic acid probes because PNA does not have any inherent backbone charges that may prevent hybridization (Brandt & Hoheisel 2004; Chambers et al. 2008). These probes are also advantageous due to their relative thermal stability compared with DNA–DNA hybridization, and allow for easy development for POC diagnostic systems (Zhang & Appella 2010). In addition, PNA probes can be designed to bind RNA directly; and since Ebola is a negative-strand RNA virus, the technology eliminates the need for any cDNA synthesis from thermal-cycling platforms. Thus, PNA tests are suitable candidates for resource-constrained regions, and could potentially be applied to POC diagnostic devices.

ImmunoPCR (iPCR)

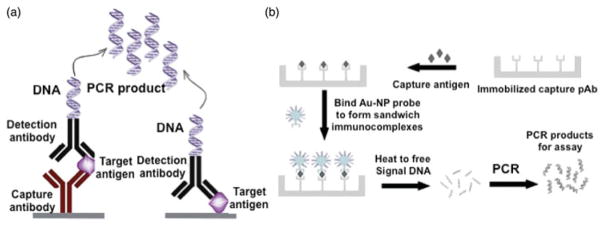

The iPCR is a next-generation biotechnology that incorporates genomic and serological techniques to create a sensitive diagnostic tool (Figure 5(a,b)). This assay utilizes a primer with a tagged end to be amplified by PCR. The amplified tag is then captured by an ELISA system, resulting in a highly sensitive test able to detect as few as 280 antigen molecules (Sano et al. 1992). iPCR has been implemented and evaluated for limit of detection on bacterial toxins, prion proteins, bacterial antigens and viral antigens (Malou & Raoult 2011). Another variant, real-time-iPCR has shown greater sensitivity and accuracy in viral detection (Barletta 2006), and shows great potential application in early and rapid detection of Ebola. As an example, Morin et al. have implemented a Real-Time-iPCR system to detect Influenza A, another single-stranded RNA virus, in the range of picomoles (Morin & Schaeffer 2012). This suggests that the iPCR is more sensitive than its precursor, ELISA, and in fact has been shown to have 100–10,000 times more sensitivity (Chambers et al. 2008). Despite the need to carry out the PCR reaction in an amplification thermocycler, there have been developments described in the implementation of iPCR into microfluidic channels (Chambers et al. 2008). This shows promise in the development of further microfluidic iPCR POC technologies that could show potential in EVD diagnosis.

Figure 5.

Immuno-PCR (iPCR) assay: iPCR technique with both variations of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), the standard for Ebola serological diagnosis; iPCR differs from ELISA by using DNA amplification of an indicator a DNA for ultrasensitive. Reprinted with copyright permission from Akter et al. (2014). (b) The sensitivity of iPCR technique is enhanced using functionalized gold nanoparticle conjugated with multiple single stranded DNA oligonucleotides. Reprinted with copyright permission from Chen et al. (2009).

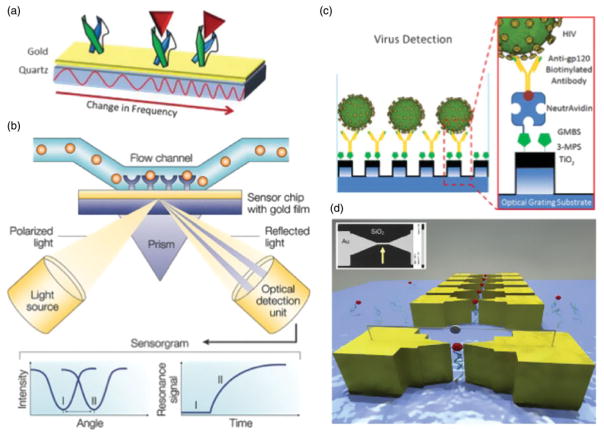

Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM), surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and photonic crystal-based label-free immunosensors

SPR and QCM-based biosensing technologies show great promise to develop POC assays as these methods are label-free (Figure 6(a,b)). Yu et al. (2006) have developed SPR and QCM immunosensors for detection of the Ebola virus GP with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. In this experiment, sensitivity is greatly increased by integrating discrete biosensing technologies, along with the use of a broad range of multiple monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies. This is possible through a QCM with a gold electrode and antibody capture matrix. Through an optical source such as a laser, the crystal frequency and resistance is measured to collect an absorption spectrum. By measuring the difference between baseline and reaction absorbance, QCM was able to detect fluctuations in absorbance in concentrations of 12 and 56 nM of EBOZ and SUDV GP, respectively (Yu et al. 2006). This suggests that if QCM biosensor is potentially developed into a POC setting, it may result in a device with low implementation cost as QCM is a label-free technology and does not require staining antibodies such as used in ELISA, yet is highly sensitive in detection.

Figure 6.

Alternative biosensing technologies for rapid and early diagnosis of Ebola. (a) Quartz crystal microbalance immunosensors are composed of a gold electrode layer with surface antibody capture agents, placed on top of a piezoelectric quartz crystal. Resonance frequency changes are measured as target binds to the antibody-coated surface, allowing for label-free detection. Reprinted with copyright permission from Kierny et al. (2012). (b) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor schematic, composed of a channel with specific antibodies fixed on a gold layer. A measurement in changes of light reflected from an optic source allows for potentially highly sensitive diagnostic capability. Reprinted with copyright permission from Cooper (2002). (c) A nanostructured photonic crystal-based sensor functionalized with gp120 to selectively capture and detect HIV copies from whole blood. Reprinted with copyright permission from Shafiee et al. (2014). (d) Break junction functionalized with aptamer to capture cancer biomarkers through electrical impedance. Reprinted with copyright permission from Ilyas et al. (2012).

The surface plasmons refer to the surface electromagnetic waves that propagate parallel along a metal/ dielectric interface. These waves are caused by discrete fluctuations in the electron density at the boundary of both metal and glass. Typically, the platform consists of a conductive metal layer such as gold and a sample capture layer that can be functionalized with antibodies or aptamers. For the SPR platform, anti-Ebola antibodies are coated onto a sensor chip, consisting of a gold plate interface and a matrix for antibody binding (Yu et al. 2006). When Ebola antigen binds with a functionalized gold surface, it produces changes in plasmon electron density fluctuations, and hence shows different absorption spectra and extinction intensity spectra when light source is applied. This allows for highly discrete sensing of viral antigen. Recently, microcavities have been fabricated and integrated with nanoplasmonic-photonics, using gold nanoshells to detect the smallest known RNA virus, MS2 (Dantham et al. 2013). This implicates surface plasmonics as potentially a beneficial technology for virus detection, and could be implemented for the detection of the EBOV, which exists 6200 + nm length in comparison with the 723 nm MS2 virus (Strauss & Sinsheimer 1963). A nanostructured photonic crystal-based label-free biosensor was also developed to capture and quantify HIV viral load (Figure 6(c)) (Shafiee et al. 2014). Surface-captured viruses produce a shift in resonance peak wavelength value enabling detection of 104–108 virus copies/ml. In a label-free LOC platform developments, these optical–crystal and plasmonics-based systems have shown to be a pertinent tool in EBOV detection, and show a potential in future EVD POC diagnostic testing (Yu et al. 2006).

Electrical sensing of viral load and biomarkers

Electrical sensing modality eliminates the need for bulky equipment required for optical-based detection systems and is a powerful and sensitive technology for the development of POC diagnostic assays. Recently, a paper microchip with printed electrodes was developed to detect and quantify multiple pathogens, including multiple HIV subtypes (A, B, C, D, E and G), Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and E. coli in fingerprick volume of plasma and artificial saliva samples with biologically relevant concentrations using electrical sensing of viral lysate (Shafiee, Asghar et al. 2015; Shafiee H, Kanakasabapathy et al. 2015). Such biosensing strategy may also be used to develop a label-free POC diagnostic assay for EBOV detection.

For the detection of protein biomarkers, nanogaps in break junctions functionalized with a target-specific aptamer have been developed. These nano-break junctions detect the capture of target molecules by measuring the change in electric current across the gap (Ilyas et al. 2012). By fabricating narrow break-junctions, bio-markers can be concentrated regionally in a flow channel to be easily detected (Figure 6(d)) (Asghar et al. 2010). Specific biomarkers of EBOV can potentially be captured and detected by functionalized nano-gaps. Binning et al. (2013) have developed RNA aptamers specific to the EBOZ VP35, a double-stranded RNA binding protein, as a potential drug. Besides the therapeutic value, these aptamers could also be immobilized to these nano-break junctions and developed into a potential label-free tool for rapid EVD diagnosis at POC. Other electrical signal-based diagnostics include antibody-functionalized nanowire arrays that measure changes in conductance, and have previously shown success at detecting Influenza A (Patolsky et al. 2004). Such devices provide an alternate and highly discrete label-free method of electrical detection through measuring changes in electrical conduction, and hold potential to capture and detect EBOV in POC settings.

LOC diagnostic platforms

The expanding field of nanotechnology demonstrates vast array of biosensor tools available (Vidyala et al. 2011; Hafeez et al. 2012; Ilyas, Asghar, Ahmed, et al. 2014; Ilyas A, Asghar W, Kim et al. 2014; Asghar et al. 2015; Rappa et al. 2016; Safavieh et al. 2017; Safavieh et al. 2016; Sher et al. 2017) for integration into accurate and sensitive methods for the detection of Ebola. Currently, conventional ideas have been miniaturized and scaled to run into diagnostic platforms. The advent of various serological assays (Sun et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2010) and nucleic acid amplification techniques (Lagally et al. 2001; Lutz et al. 2010) integrated on-a-chip demonstrate the successful assimilation of conventional serological and nucleic acid detection methods. Sun et al. (2011) created a LOC device for the detection of viral RNA from influenza using a nucleic acid separation, RT-PCR and microarray separation. The next generation of hand-held POC devices can leverage several different arrays of test and truly define the standard of LOC diagnostics. Gaster et al. (2011) developed a device called nanoLAB, capable for deployment for individual use in potentially resource-limited areas around the world for disease detection. Such complex and miniaturized conventional laboratory experiments for detection are reduced significantly in time through automation and miniaturization, and lead to efficient sample and reagent consumption, which drive the creation of novel, next-generation high-throughput diagnostic systems for EVD.

Summary

In this review, we performed an exhaustive analysis of the benefits and limitations of various conventional and possible non-conventional diagnostic methods for EVD detection, and demonstrated the usefulness of novel biosensors that can be leveraged into potential diagnostic microfluidic platforms. When compared with the effort, logistical cost, effectiveness and reliability, POC devices are favoured to become the vanguard for diagnostic platforms, and show great value in the areas affected by EVD. Traditional methods of EBOV detection rely on the availability of necessary reagents, and require close contact with infected samples, which motivate the concern for developing safe and efficient methods. RT-PCR is the most sensitive and requires several tightly controlled processes to obtain a reliable result. Numerous technologies presented have potential capability to meet these drawbacks. First, RNA processing can potentially further be simplified through leveraging the advantages of many new different device fabrication techniques, and incorporation of both isolation and detection of nucleic acids. Assays can be designed to be automated, and can be performed rapidly at POC settings, while potentially increasing sensitivity of molecular-based assays. ELISA and other serological methods are other highly sensitive methods for the detection of EVD, and are highly specific to different Ebola virus species and strains. However, the sensitivity of these assays has not met the success of the current RT-PCR methods, and there is potential to increase sensitivity through nanotechnology and novel LOC-based sensing platforms. Several diagnostic assays using molecular and serological detection were employed under emergency authorization for the 2014 West African EVD outbreak. This demonstrates global shift toward implantation of point-of-care testing to help control the spread of EVD. Portable, reliable and LOC technologies can achieve higher sensitivity and quicker assay turnaround time by leveraging many of the future diagnostic advances described here. These advances will reduce the sample and reagent volumes, and decreased the assay cost for providers. Development of assays utilizing novel detection methods is compared with previously validated EVD kits, in particular RT-PCR, however, lack the essential diagnostic performance and clinical testing in outbreak settings. In the future, such assays can be subjected to testing through experimental use in parallel with established EVD diagnosis protocols to validate them as viable assays in future EVD outbreaks.

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [R15AI127214].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

Authors declare no financial conflict of interest.

References

- Akter F, Mie M, Kobatake E. DNA-based immunoassays for sensitive detection of protein. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2014;202:1248–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Alazard-Dany N, Terrangle MO, Volchkov V. Ebola et Marburg: les hommes contre-attaquent. M/S: Méd Sci. 2006;22:405–410. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2006224405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar W, El Assal R, Shafiee H, Pitteri S, Paulmurugan R, Demirci U. Engineering cancer microenvironments for in vitro 3-D tumor models. Mater Today. 2015;18:539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar W, Ilyas A, Billo JA, Iqbal SM. Shrinking of solid-state nanopores by direct thermal heating. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar W, Ilyas A, Deshmukh RR, Sumitsawan S, Timmons RB, Iqbal SM. Pulsed plasma polymerization for controlling shrinkage and surface composition of nanopores. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:285304. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/28/285304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar W, Ramachandran PP, Adewumi A, Noor MR, Iqbal SM. Rapid nanomanufacturing of metallic break junctions using focused ion beam scratching and electromigration. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2010;132:030911. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar W, Wan Y, Ilyas A, Bachoo R, Kim Y-T, Iqbal SM. Electrical fingerprinting, 3D profiling and detection of tumor cells with solid-state micropores. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2345–2352. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21012f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar W, Yuksekkaya M, Shafiee H, Zhang M, Ozen MO, Inci F, Kocakulak M, Demirci U. Engineering long shelf life multi-layer biologically active surfaces on microfluidic devices for point of care applications. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep21163. Article: 21163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylward B, Barboza P, Bawo L, Bertherat E, Bilivogui P, Blake I. Ebola virus disease in West Africa-the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1481–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barletta J. Applications of real-time immunopolymerase chain reaction (rt-IPCR) for the rapid diagnosis of viral antigens and pathologic proteins. Mol Asp Med. 2006;27:224–253. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausch DG, Schwarz L. Outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Guinea: where ecology meets economy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla N, Chung DWY, Chang Y-J, Uy KJS, Ye YY, Chin T-Y, Yang HC, Pijanowska DG. Microfluidic platform for enzyme-linked and magnetic particle-based immunoassay. Micromachines. 2013;4:257–271. doi: 10.3390/mi4020257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binning JM, Wang T, Luthra P, Shabman RS, Borek DM, Liu G, Xu W, Leung DW, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. Development of rna aptamers targeting ebola virus vp35. Biochemistry. 2013;52:8406–8419. doi: 10.1021/bi400704d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouree P, Bergmann J-F. Ebola virus infection in man: a serological and epidemiological survey in the Cameroons. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:1465–1466. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt O, Hoheisel JD. Peptide nucleic acids on microarrays and other biosensors. TRENDS Biotechnol. 2004;22:617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst MJ, Brooks TJ, Pollock NR. Diagnosis of Ebola virus disease: past, present, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29:773–793. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00003-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst MJ, Kelly JD, Miller A, Semper A, Bailey D, Groppelli E, Simpson A, Brooks T, Hula S, Nyoni W, et al. ReEBOV Antigen Rapid Test kit for point-of-care and laboratory-based testing for Ebola virus disease: a field validation study. Lancet. 2015;386:867–874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Parks JW, Carrion R, Zempoaltecatl L, Patterson JP, Hawkins A, Schmidt H. Proceedings of the CLEO: Science and Innovations. Optical Society of America; 2014. On-chip detection of clinical Ebola virus RNA using specific DNA binding technique. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo MF, Kats AM, Chen R, Hartmann JX, Pavlovic M. Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases. 2012. A novel method for real-time, continuous, fluorescence-based analysis of anti-DNA abzyme activity in systemic lupus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/814048. Available from http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/agent-list-category.asp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chambers JP, Arulanandam BP, Matta LL, Weis A, Valdes JJ. Biosensor recognition elements. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2008;10:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changula K, Yoshida R, Noyori O, Marzi A, Miyamoto H, Ishijima M, Yokoyama A, Kajihara M, Feldmann H, Mweene AS, et al. Mapping of conserved and species-specific antibody epitopes on the Ebola virus nucleoprotein. Virus Res. 2013;176:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wei H, Guo Y, Cui Z, Zhang Z, Zhang X-E. Gold nanoparticle enhanced immuno-PCR for ultrasensitive detection of Hantaan virus nucleocapsid protein. J Immun Meth. 2009;346:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpillod P, Schibler M, Vieille G, Cordey S, Mamin A, Vetter P, Kaiser L. Ebola virus disease diagnosis by real-time RT-PCR: a comparative study of 11 different procedures. J Clin Virol. 2016;77:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P. Shelf-stable product and process for isolating RNA, DNA and proteins. Google Patents 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Chua AC, Cunningham J, Moussy F, Perkins MD, Formenty P. The case for improved diagnostic tools to control Ebola virus disease in West Africa and how to get there. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;119:e0003734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA. Optical biosensors in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:515–528. doi: 10.1038/nrd838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, Singleton VT. A survey of the 2001 to 2005 quartz crystal microbalance biosensor literature: applications of acoustic physics to the analysis of biomolecular interactions. J Mol Recogn. 2007;20:154–184. doi: 10.1002/jmr.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantham VR, Holler S, Barbre C, Keng D, Kolchenko V, Arnold S. Label-free detection of single protein using a nanoplasmonic-photonic hybrid microcavity. Nano Lett. 2013;13:3347–3351. doi: 10.1021/nl401633y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon RS, Srikrishna D, Garry RF, Chowell G. Ebola control: rapid diagnostic testing. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:147–148. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon RS, Srikrishna D, Sachs J. Controlling Ebola: next steps. Lancet. 2014;384:1409–1411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis: Ebola hemorrhagic fever. 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa – case counts [Internet] 2014 Nov 14; [cited 2016 Mar 4]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/case-counts.html.

- Drosten C, Göttig S, Schilling S, Asper M, Panning M, Schmitz H, Günther S. Rapid detection and quantification of RNA of Ebola and Marburg viruses, Lassa virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Rift Valley fever virus, dengue virus, and yellow fever virus by real-time reverse transcription-PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2323–2330. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2323-2330.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esiobu N, Mohammed R, Echeverry A, Green M, Bonilla T, Hartz A, McCorquodale D, Rogerson A. The application of peptide nucleic acid probes for rapid detection and enumeration of eubacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in recreational beaches of S. Florida J Microbiol Methods. 2004;57:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzarano D, Krokhin O, Wahl-Jensen V, Seebach J, Wolf K, Schnittler HJ, Feldmann H. Structure–function analysis of the soluble glycoprotein, sGP, of Ebola virus. Chembiochem. 2006;7:1605–1611. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H, Geisbert TW. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2011;377:849–862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint M, Goodman CH, Bearden S, Blau DM, Amman BR, Basile AJ, Belser JA, Bergeron E, Bowen MD, Brault AC, et al. Ebola Virus Diagnostics: The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Laboratory in Sierra Leone, August 2014 to March 2015. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(Suppl 2):S350–S358. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Schwarz G, Rogacs A, Bahga SS, Santiago JG. On-chip isotachophoresis for separation of ions and purification of nucleic acids. J Vis Exp. 2012;61:e3890. doi: 10.3791/3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaster RS, Hall DA, Wang SX. nanoLAB: an ultraportable, handheld diagnostic laboratory for global health. Lab Chip. 2011;11:950–956. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb TR, Norwood DA, Woollen N, Henchal EA. Development and evaluation of a fluorogenic 5’ nuclease assay to detect and differentiate between Ebola virus subtypes Zaire and Sudan. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:4125–4130. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.4125-4130.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gire SK, Goba A, Andersen KG, Sealfon RS, Park DJ, Kanneh L, Jalloh S, Momoh M, Fullah M, Dudas G. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science. 2014;345:1369–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.1259657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolla A, Lucht A, Dick D, Strong J, Feldmann H. Laboratory diagnosis of Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever. Bull – Soc Pathol Exotique. 2005;98:205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidance for U.S. laboratories for managing and testing routine clinical specimens when there is a concern about Ebola virus disease [Internet] [cited 2015 Nov 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/healthcare-us/laboratories/safe-specimen-management.html.

- Günther S, Asper M, Röser C, Luna LKS, Drosten C, Becker-Ziaja B, Borowski P, Chen H-M, Hosmane RS. Application of real-time PCR for testing antiviral compounds against Lassa virus, SARS coronavirus and Ebola virus in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2004;63:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo MT, Rotem A, Heyman JA, Weitz DA. Droplet microfluidics for high-throughput biological assays. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2146–2155. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21147e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeez A, Asghar W, Rafique MM, Iqbal SM, Butt AR. GPU-based real-time detection and analysis of biological targets using solid-state nanopores. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2012;50:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s11517-012-0893-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heid CA, Stevens J, Livak KJ, Williams PM. Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 1996;6:986–994. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch LR, Jackson JB, Lee A, Halas NJ, West JL. A whole blood immunoassay using gold nanoshells. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2377–2381. doi: 10.1021/ac0262210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Wei H, Wang Y, Shi Z, Raoul H, Yuan Z. Rapid detection of filoviruses by real-time TaqMan polymerase chain reaction assays. Virol Sin. 2012;27:273–277. doi: 10.1007/s12250-012-3252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami T, Saijo M, Niikura M, Miranda M, Calaor A, Hernandez M, Manalo D, Kurane I, Yoshikawa Y, Morikawa S. Immunoglobulin G enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using truncated nucleoproteins of Reston Ebola virus. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;130(3):533–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas A, Asghar W, Ahmed S, Lotan Y, Hsieh J-T, Kim Y-T, Iqbal SM. Electrophysiological analysis of biopsy samples using elasticity as an inherent cell marker for cancer detection. Anal Methods. 2014;6:7166–7174. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas A, Asghar W, Allen PB, Duhon H, Ellington AD, Iqbal SM. Electrical detection of cancer biomarker using aptamers with nanogap break-junctions. Nanotechnology. 2012;23:275502. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/27/275502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas A, Asghar W, Kim Y-t, Iqbal SM. Parallel recognition of cancer cells using an addressable array of solid-state micropores. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;62:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung B, Ness K, Rose KA. Methods for separating particles and/or nucleic acids using isotachophoresis. Google Patents 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Kallstrom G, Warfield KL, Swenson DL, Mort S, Panchal RG, Ruthel G, Bavari S, Aman MJ. Analysis of Ebola virus and VLP release using an immunocapture assay. J Virol Methods. 2005;127:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra S, Kelkar D, Galwankar SC, Papadimos TJ, Stawicki SP, Arquilla B, Hoey BA, Sharpe RP, Sabol D, Jahre JA. The emergence of ebola as a global health security threat: from ‘lessons learned’ to coordinated multilateral containment efforts. J Global Infect Dis. 2014;6:164. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.145247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata T, Natesan M, Warfield K, Aman MJ, Ulrich RG. Determination of specific antibody responses to the six species of Ebola and Marburg viruses by multiplexed protein microarrays. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:1605–1612. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00484-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandurina J, McKnight TE, Jacobson SC, Waters LC, Foote RS, Ramsey JM. Integrated system for rapid PCR-based DNA analysis in microfluidic devices. Anal Chem. 2000;72:2995–3000. doi: 10.1021/ac991471a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierny MR, Cunningham TD, Kay BK. Detection of bio-markers using recombinant antibodies coupled to nanostructured platforms. Nano Rev Exp. 2012;3:17240. doi: 10.3402/nano.v3i0.17240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]