Abstract

Purpose of review

HOXA9 is a homeodomain transcription factor that plays an essential role in normal hematopoiesis and acute leukemia, where its over expression is strongly correlated with poor prognosis. This review highlights recent advances in the understanding of genetic alterations leading to deregulation of HOXA9 and the downstream mechanisms of HOXA9-mediated transformation.

Recent findings

A variety of genetic alterations including MLL-translocations, NUP98-fusions, NPM1 mutations, CDX deregulation, and MOZ-fusions lead to high level HOXA9 expression in acute leukemias. The mechanisms resulting in HOXA9 over expression are beginning to be defined and represent attractive therapeutic targets. Small molecules targeting MLL-fusion protein complex members, such as DOT1L and menin, have shown promising results in animal models, and a DOT1L inhibitor is currently being tested in clinical trials. Essential HOXA9 cofactors and collaborators are also being identified, including transcription factors PU.1 and C/EBPα, which are required for HOXA9-driven leukemia. HOXA9 targets including IGF1, CDX4, INK4A/INK4B/ARF, mir-21 and mir-196b and many others provide another avenue for potential drug development.

Summary

HOXA9 deregulation underlies a large subset of aggressive acute leukemias. Understanding the mechanisms regulating the expression and activity of HOXA9, along with its critical downstream targets, shows promise for the development of more selective and effective leukemia therapies.

Keywords: HOXA9, MEIS1, MLL, AML

INTRODUCTION

Homeobox proteins are a family of homeodomain-containing transcription factors, first identified in Drosophila, that control cell fate and segmental identity during development (1, 2). In mammals the 39 class 1 homeobox, or HOX genes, are arranged into four parologous clusters (A, B, C and D) on separate chromosomes (3, 4). In addition to their role in regulating development, a subset of A and B cluster HOX genes also play crucial roles in regulating hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis (5–7). Of these, HOXA9 has been most intensively studied as it is over expressed in more than 50% of acute myeloid leukemias and in a subset of B and T acute lymphoblastic leukemias (8–10). Understanding the HOXA9 axis—how its expression is regulated in normal and neoplastic states, how it regulates transcription and which downstream targets are essential for transformation—may lead to new therapies in leukemia and other hematologic malignances.

DEREGULATION OF HOXA9 IN ACUTE LEUKEMIA

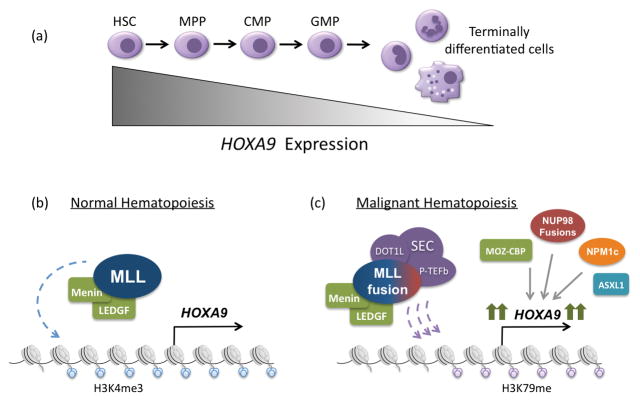

HOXA9 is expressed in high levels in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and early progenitors, and its expression is down regulated with further differentiation (Figure 1a) (11). Hoxa9-deficient mice show mild pancytopenia and decreased spleen and thymus cellularity (12). Conversely, over expression of Hoxa9 in mice leads to HSC expansion and a myeloproliferative disorder that progresses to AML (5). The onset of these leukemias is rapidly accelerated by coexpression of HOX cofactors, MEIS1 and PBX3, which are often coexpressed at high levels with HOXA9 in human leukemias (13–16).

Figure 1.

Regulation of HOXA9 expression in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. (a) During normal hematopoiesis, HOXA9 is expressed most highly in early progenitor cells and its expression is subsequently down regulated as cells become terminally differentiated. (b) In normal hematopoiesis, HOXA9 expression is regulated by the MLL histone methytransferase, which deposits activating histone 3, lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) along the HOXA9 locus. This process requires interaction with menin and its cofactor LEDGF. (c) In approximately 50% of acute leukemias, HOXA9 is highly expressed as the result of a variety of upstream genetic alterations. These include MLL1-fusions, NUP98-fusions, MOZ-CBP fusions, NPM1c mutations and ASXL1 mutations. In the case of MLL1-fusions, one of 60 translocations partners is fused to the C-terminus of MLL, resulting in recruitment of the SEC (including DOT1L) and PTEF-b complexes. DOT1L is responsible for depositing activating histone 3 lysine 79 methylation, leading to high HOXA9 expression and malignant transformation. The other genetic abnormalities also result in high HOXA9 expression, though the mechanisms are less well understood.

A variety of upstream genetic alterations can lead to deregulation of HOXA9, including MLL1-translocations, NUP98-fusions, NPM1 mutations, CDX deregulation, MOZ-fusions as well as translocations involving HOXA9 itself (17). Regardless of the mechanism of deregulation, high-level HOXA9 expression appears to be a strong independent adverse prognostic factor in acute leukemia (8, 9, 18).

MLL1-Fusion Proteins

Chromosomal translocations involving the mixed lineage leukemia gene MLL1 at chromosome 11q23 occur in about 10% of AML (19, 20). MLL1 (also known as KMT2A) is a large protein of nearly 4000 amino acids, which is one of five mammalian MLL proteins that are homologous to the Drosophila protein Trithorax, a positive regulator of homeobox gene expression in the fly. All MLL proteins share a C terminal SET domain that has methyltransferase activity specific for histone H3 lysine 4. MLL family members antagonize the action of Polycomb group proteins, which form multi-subunit complexes that have histone H3 lysine 27 methyltransferase activity. MLL1 has been shown to be required for normal hematopoiesis at least in part due to its ability to regulate HOX gene expression (Figure 1b) (21). Increasing evidence suggest this involves not only histone methylation, but also recruitment of the histone acetyltransferase MOF (22).

Leukemia associated MLL1-translocations result in fusion of MLL1 to one of over 60 different translocation partners and deletion of the coding regions for the central PHD domains and C terminal SET domain. Nine translocation partners AF1p, AF4, AF6, AF7, AF10, AF17, ENL, ELL, and SEPT7 comprise 90% of MLL translocations (23). These include both nuclear factors (such as AF4, AF9 and ENL) and less common cytoplasmic partners, such as AF1p and SEPT7 (24). MLL-fusion proteins enforce high-level HOXA9 expression, which is required for transformation in most experimental models (25, 26). This mechanism involves recruitment of at least two complexes important for transcriptional regulation. One, the super elongation complex (SEC), contains common MLL-translocation partners ELL, ENL or AF9, AF4 and positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb), which includes the cyclin-dependent kinases CDK9 and Cyclin-T (27). The other complex includes the histone methyltransferase DOT1L, which specifically methylates histone H3 lysine 79, and the MLL-translocation partners AF10, AF17 AF9 and ENL. MLL-fusion proteins either directly or indirectly recruit the P-TEFb and DOT1L complexes to the HOXA locus, resulting in large increases in histone H3 lysine 79 methylation and high level transcription (Figure 1c) (28). DOT1L inhibitors have been shown to have efficacy for MLL-rearranged leukemias and are currently being tested in clinical trials (29, 30).

Partial tandem duplications involving the sequence encoding the N-terminus of MLL are observed in about 10% of cytogenetically normal AML and are also associated with HOXA9 over expression (31). Interestingly, these have been shown to be sensitive to DOT1L inhibition, despite the fact that they do not involve fusion with partners that interact with DOT1L (32).

Another attractive therapeutic target for MLL-rearranged leukemias is menin, which interacts with the amino terminus of both MLL and MLL-fusion proteins and is required for their recruitment to specific chromosomal sites (Figure 1b). Small molecule inhibitors of the MLL-menin interaction, which are under active development, show considerable efficacy in killing AML cells in vitro as well as in animal models (33).

Nucleoporin-fusion proteins

Nucleoporins are members of the nuclear pore complex (NPC), which facilitates shuttling of metabolites and molecules between the cytoplasm and nucleus and also plays a role in promoting euchromatic transcription (34, 35). NUP98 and less commonly NUP214, are involved in a number of chromosomal translocations in acute leukemia (reviewed in more detail in (36)). NUP98-translocations include fusions with clustered HOX genes (A9, A11, A13, C11, C13, D11 and D13), non-clustered HOX genes (HHEX, PRRX1, PRRX2), and non-HOX genes such as NSD1 and JARID1A (37). These fusions result in HOX gene up regulation, which contributes to leukemogenesis (38). AML and AMKL cases harboring NUP98-translocations show consistent HOXA and HOXB cluster up regulation, with an overall gene expression signature that is distinct from MLL-rearranged leukemias (39, 40).

NPM1 mutation

Mutations of the chaperone protein nucleophosmin1 (NPM1) are common, occurring in about 50–60% of AMLs (41, 42). Leukemia-associated NPM1 mutations create an additional nuclear export signal resulting in relocalization of NPM1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (43). Cytoplasmic NPM1 (NPM1c) up regulates the expression of HOXA9, HOXA10 and MEIS1, possibility as a result of cytoplasmic sequestration of HEXIM1 by NPM1c, which subsequently activates P-TEFb (44–46).

Other mechanisms of HOXA9 deregulation

Many additional upstream genetic alterations lead to HOXA9 deregulation in acute leukemia (17). Deletions or decreased expression of the polycomb protein EZH2 leads to leukemia with up regulation of HOXA9 (47). Similarly mutations in the polycomb gene ASLX1 are common in myelodysplastic syndromes and are associated with high expression of HOXA9 (48). In addition, fusion of CDX2 and ETV6 (ETV6-CDX2) is seen in rare cases of AML, resulting in high level CDX2 expression, which promotes HOXA9 expression (49, 50). Chromosomal translocations generating the CALM-AF10 (PICALM-MLLT10) fusion leads to HOXA cluster up regulation in T-ALL and some AML cases (38, 51). The MYST-CREBBP (MOZ-CBP) is seen in de novo and therapy-related AML cases and is also associated with HOXA9 and MEIS1 up regulation (52). Finally, rare cases of T-ALL harbor translocations involving the HOXA9 locus with the T cell receptor β locus, which results in high-level HOXA9 expression (53).

TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION AND TRANSFORMATION BY H/M

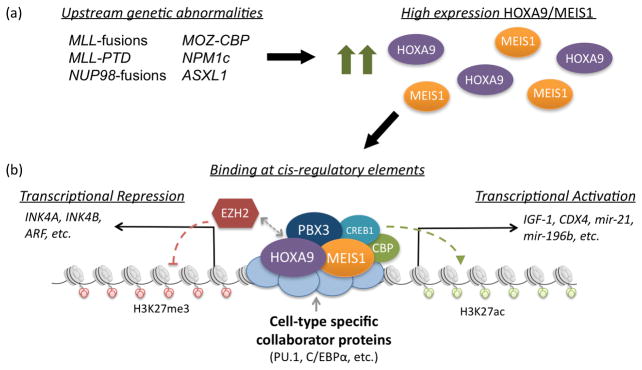

The mechanisms through which HOXA9 regulates downstream gene expression and specific targets that are essential to transformation are areas of active investigation. It is clear that HOXA9 is a member of both activating and repressive transcriptional regulatory complexes, which include cofactor and collaborator proteins that provide target specificity and stabilization on the DNA, as well as epigenetic modifiers and transcriptional machinery (Figure 2) (54–56). Early studies with small molecules disrupting protein interactions in HOXA9-complexes have been successful at killing leukemia cells both in vitro and in murine studies (16, 57–59). In addition, critical downstream targets of HOXA9 in leukemia are being more rapidly identified, providing another avenue for targeted therapies in AML. Two comprehensive review articles were recently published discussing HOX protein function (60, 61). In the following section, we will highlight the latest publications related to HOXA9 and its cofactors in leukemia.

Figure 2.

Model for HOXA9-mediated leukemogenesis. (a) A variety of upstream genetic abnormalities are associated with high expression of HOXA9 and its cofactor MEIS1, both of which are known to play an essential role in acute leukemias. (b) HOXA9 and MEIS1 promote malignant transformation through binding at cis-regulatory elements throughout the genome, whereby they activate and repress downstream gene expression. The targeting and stabilization of HOXA9/MEIS1 at specific loci is likely mediated by cell-type specific collaborator proteins, such as PU.1 and C/EBPα. Upon binding at loci along with the additional cofactor PBX3, HOXA9/MEIS1 recruit coactivating and corepressing histone modifying complexes, such as CREB1/CBP and EZH2 respectively. Recently established activated targets include IGF-1, CDX4, mir-21 and mir-196b. Recently established repressed targets include INK4A, INK4B and ARF.

Cofactors

HOX proteins regulate downstream gene expression through direct binding at cis-regulatory elements via their highly conserved homeodomains. These 60-amino acid domains are responsible for binding to DNA and for providing an interface mediating protein-protein interactions (62, 63). While homeodomains are highly conserved across the 39 mammalian HOX proteins, multiple studies suggest that homeodomains confer unique properties via their small differences (64, 65). For example, swapping the homeodomains of HOXA9 and HOXA1 abolishes the leukemogenic properties of HOXA9 while conferring those properties to HOXA1 (66).

HOXA9 binds DNA along with a small subset of cofactors, many of which are members of the Three-amino-acid-loop-extension (TALE) family. The best characterized of these cofactors is MEIS1, which plays a synergistic causative role in leukemia with HOXA9 (14, 15). A recent study with Meis1 knockout/MLL-AF9 knockin murine model established that Meis1 is required for development of MLL-AF9 driven leukemias (67). This requirement is partially mediated through promoting a low oxidative environment established by direct regulation of HLF by Meis1. In addition, MEIS1 is responsible for recruiting CREB and CBP to HOXA9 binding sites in a GSK-3 dependent manner, which is required for maintaining the MLL leukemia stem cell transcriptional program (58). This interaction can be targeted using GSK-3 inhibitors, leading to growth inhibition of cells transformed by either HOXA9/MEIS1 or MLL-fusion proteins (57–59). The oncogenic properties of MEIS1 are antagonistically regulated by PREP1, another TALE family protein, through direct competition for binding sites (68). PREP1 also competitively heterodimerizes and sequesters PBX proteins, thereby decreasing stability of MEIS1 and preventing the MEIS1-DDX3x/DDX5 interactions that are required for tumorigenesis (69, 70). Furthermore, in vivo leukemogenesis studies with HOXA9/MEIS1 in PREP1-deficient cells showed more aggressive leukemias compared to wild-type (69).

Recent work has characterized the requirement of a second TALE cofactor, PBX3, in the setting of leukemia with high expression of HOXA9. PBX3, and not PBX1 or PBX2, was found to be essential for MLL-fusion protein mediated transformation. Disruption of the PBX3/HOXA9 interaction with the small molecule HXR9 selectively kills leukemic cells, providing a promising strategy for developing future therapies (16). PBX3 also dimerizes with MEIS1 and inhibits its ubiquitination and degradation, thereby increasing the half-life of MEIS1 and enhancing the proliferation and colony forming ability of primary cells transduced by HOXA9 (71). This MEIS1/PBX3 dimerization is required for expression of HOXA9/MEIS1 target genes such as FLT3 and TRIB2 (71). Moreover, coexpression of MEIS1/PBX3 is sufficient to transform cells in culture and lead to formation of leukemia in vivo with similar latency to that of MLL-AF9 (72). Expression patterns in cells transformed by MEIS1/PBX3 are consistent with that of the MLL-AF9 core transcriptome, including upregulation of HOXA9 (72).

Collaborators

It is likely that tissue specific collaborator proteins provide a final level of binding specificity to HOX complexes (73). Recent work has shown that collaborators establish areas of chromatin accessibility, provide stability in DNA binding and help modulate the downstream activity of HOX complexes (74). Two such collaborators are the lineage-specific transcription factors, PU.1 and C/EBPα, which are known to establish areas of relaxed chromatin and allow for signal-dependant recruitment of additional proteins (75). PU.1 was recently found to be essential for MLL-induced leukemias and was shown to directly regulate key genes in the HOX/MEIS signature, including FLT3 and c-KIT (76). Taken together with previously published work, which found that HOXA9 and PU.1 physically interact and that the PU.1 binding motif is enriched at HOXA9 binding sites, these findings suggest PU.1 may be an essential member of a HOXA9 transcriptional regulatory complex (54). PU.1 also plays a role in leukemias without MLL-translocations, potentially through direct activation of MEIS1 via binding at the MEIS1 promoter (77).

Multiple recent publications have established that C/EBPα is required for MLL-fusion protein and HOXA9-driven leukemias. Initial studies found that the initiation of MLL-ENL transformed leukemias required C/EBPα, whereas it was not required for maintenance of transformation (78). Loss of C/EBPα in MLL-ENL transformed cells also resulted in decreased expression of HOXA9/MEIS1, however expression of HOXA9/MEIS1 could not rescue transformation in these cells. Work from our lab found that loss of C/EBPα significantly improved survival in murine in vivo leukemogenesis models of HOXA9/MEIS1-driven AML (10). We also established that C/EBPα and HOXA9 physically interact and colocalize at over 50% of HOXA9 binding sites, raising the possibility that C/EBPα is an essential member of the HOXA9-transcriptional regulatory complex. More recent work also suggests that C/EBPα-driven myeloid differentiation, rather than C/EBPα itself, is required for initiation of MLL-rearranged leukemia (79). The failed transformation of MLL-AF9 in C/EBPα deleted cells could be rescued with cytokine induction of GMP formation. It is possible that this requirement is due to the need for myeloid specific enhancers for proper downstream HOXA9 function. Similarly, it is likely that collaborators such as PU.1 and C/EBPα are cell type-specific and that HOXA9 would have different collaborators in B and T-cell leukemias.

Targets in leukemia

Considerable progress has been made towards understanding HOXA9-mediated leukemogenesis through the identification of proleukemic targets with cis-regulatory regions bound by HOXA9 and MEIS1 (54). Many of these targets have been studied individually and found to play important roles in leukemic transformation (comprehensively reviewed in (60)). Recently additional critical targets have been identified and mechanistically studied. HOXA9 was shown to regulate IGF1 expression through binding at an upstream putative promoter and DNA hypersensitive region in intron 1 (80). IGF1-null cells transformed by HOXA9 have reduced leukemogenic potential and increased apoptosis in response to serum starvation. HOXA9 is also involved in a feedback loop along with HOXA10 that directly regulates CDX4 expression during normal hematopoietic differentiation (81). In the context of leukemia, MLL-ELL cooperates with constitutively activated SHP2 mutants to block the tyrosine phosphorylation of HOXA9/10 that is required for repression of CDX4, thereby contributing to the sustained expression of CDX4 and leukemic transformation (81).

Multiple studies have implicated a role for HOXA9 in the regulation of INK4A/B expression, critical mediators of HSC self-renewal, apoptosis and oncogene-induced senescence whose expression leads to a block in cell cycle at the G1 phase (82). Hoxa9 represses Ink4a expression to overcome oncogene-induced senescence during transformation by AML1-ETO in Bmi1−/− cells, as well as in Hoxa9/Meis1 transformed cells (10, 83). This repression may be the result of direct recruitment of EZH2 by Hoxa9, however recent work suggests that EZH2 may also regulate p16 in HOXA9-independent fashion in MLL-rearranged leukemias (84, 85).

Finally, HOXA9 is involved in antagonistic regulation of GFI-1 target microRNAs, mir-21 and mir-196b, whereby direct binding of HOXA9 to cis-regulatory regions increases expression of these microRNAs (86). Targeting mir-21 and mir-196b with antagomirs results in specific inhibition of colony forming activity and leukemia-initiating cell activity in HOXA9, NUP98-HOXA9, and MLL-AF9, and also leads to leukemia-free survival in MLL-AF9 murine leukemogenesis studies. Furthermore, samples from patients with MLL-translocated and NPM1 mutant leukemias showed specific growth inhibition in colony forming assays when treated with the antagomirs, providing a promising therapeutic approach for HOXA9 driven AML (86).

CONCLUSION

While significant progress has been made towards our understanding of the genetic alterations leading to deregulation of HOXA9 and the mechanisms of HOXA9-mediated transformation, many answered questions remain. It will be important to identify the cofactors, interactions and downstream activities of HOXA9 that are essential for leukemogenesis. HOXA9 is associated with both activation and repression of transcription, with the latter being particularly poorly understood. In addition, the downstream targets that are essential for leukemogenesis are only beginning to be defined using genome-wide screening. Given the central role of HOXA9 proteins in development and oncogenesis, further work is warranted which may have broad applicability towards the development of more potent and selective therapies.

KEY POINTS.

HOXA9 is highly expressed in a variety of hematopoietic malignancies and is generally associated with poor prognosis.

A variety of upstream genetic alterations lead to high expression of HOXA9 including MLL1-translocations, NUP98-fusions, NPM1c mutations, CDX dysregulation, MOZ-fusions and translocations of HOXA9 itself.

Small molecules inhibitors targeting DOT1L and menin are showing efficacy in HOXA9-driven leukemia models.

HOXA9 regulates gene expression through binding at cis-regulatory elements with a subset of essential cofactors (MEIS1 and PBX3) and cell-type specific collaborators (PU.1, C/EBPα).

Further study of HOXA9-mediated leukemogenesis is warranted given its central role in development and oncogenesis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

References

- 1.Goodman FR. Limb malformations and the human HOX genes. American journal of medical genetics. 2002;112(3):256–65. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis EB. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature. 1978;276(5688):565–70. doi: 10.1038/276565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krumlauf R. Hox genes in vertebrate development. Cell. 1994;78:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duboule D, Dolle P. The structural and functional organization of the murine HOX gene family resembles that of Drosophila homeotic genes. The EMBO journal. 1989;8(5):1497–505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alharbi RA, Pettengell R, Pandha HS, Morgan R. The role of HOX genes in normal hematopoiesis and acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(5):1000–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eklund E. The role of Hox proteins in leukemogenesis: insights into key regulatory events in hematopoiesis. Crit Rev Oncog. 2011;16(1–2):65–76. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v16.i1-2.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitwala K, Dandekar M, Hess J. HOX Proteins and Leukemia. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:461–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreeff M, Ruvolo V, Gadgil S, Zeng C, Coombes K, Chen W, et al. HOX expression patterns identify a common signature for favorable AML. Leukemia. 2008;22(11):2041–7. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286(5439):531–7. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10•.Collins C, Wang J, Miao H, Bronstein J, Nawer H, Xu T, et al. C/EBPalpha is an essential collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated leukemogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(27):9899–904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402238111. This study established that C/EBPα is required for Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated leukemogenesis and that C/EBPα colocalizes at over 50% of Hoxa9 binding sites throughout the genome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pineault N, Helgason CD, Lawrence HJ, Humphries RK. Differential expression of Hox, Meis1, and Pbx1 genes in primitive cells throughout murine hematopoietic ontogeny. Experimental hematology. 2002;30(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00757-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence HJ, Helgason CD, Sauvageau G, Fong S, Izon DJ, Humphries RK, et al. Mice bearing a targeted interruption of the homeobox gene HOXA9 have defects in myeloid, erythroid, and lymphoid hematopoiesis. Blood. 1997;89(6):1922–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence HJ, Rozenfeld S, Cruz C, Matsukuma K, Kwong A, Komuves L, et al. Frequent co-expression of the HOXA9 and MEIS1 homeobox genes in human myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 1999;13(12):1993–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroon E, Krosl J, Thorsteinsdottir U, Baban S, Buchberg AM, Sauvageau G. Hoxa9 transforms primary bone marrow cells through specific collaboration with Meis1a but not Pbx1b. The EMBO journal. 1998;17(13):3714–25. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorsteinsdottir U, Mamo A, Kroon E, Jerome L, Bijl J, Lawrence HJ, et al. Overexpression of the myeloid leukemia-associated Hoxa9 gene in bone marrow cells induces stem cell expansion. Blood. 2002;99(1):121–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Zhang Z, Li Y, Arnovitz S, Chen P, Huang H, et al. PBX3 is an important cofactor of HOXA9 in leukemogenesis. Blood. 2013;121(8):1422–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Braekeleer E, Douet-Guilbert N, Basinko A, Le Bris MJ, Morel F, De Braekeleer M. Hox gene dysregulation in acute myeloid leukemia. Future Oncol. 2014;10(3):475–95. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adamaki M, Lambrou GI, Athanasiadou A, Vlahopoulos S, Papavassiliou AG, Moschovi M. HOXA9 and MEIS1 gene overexpression in the diagnosis of childhood acute leukemias: Significant correlation with relapse and overall survival. Leuk Res. 2015;39(8):874–82. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7(11):823–33. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muntean AG, Hess JL. The pathogenesis of mixed-lineage leukemia. Annual review of pathology. 2012;7:283–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gan T, Jude CD, Zaffuto K, Ernst P. Developmentally induced Mll1 loss reveals defects in postnatal haematopoiesis. Leukemia. 2010;24(10):1732–41. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra BP, Zaffuto KM, Artinger EL, Org T, Mikkola HK, Cheng C, et al. The histone methyltransferase activity of MLL1 is dispensable for hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Cell reports. 2014;7(4):1239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer C, Kowarz E, Hofmann J, Renneville A, Zuna J, Trka J, et al. New insights to the MLL recombinome of acute leukemias. Leukemia. 2009;23(8):1490–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.So CW, Lin M, Ayton PM, Chen EH, Cleary ML. Dimerization contributes to oncogenic activation of MLL chimeras in acute leukemias. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(2):99–110. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayton PM, Cleary ML. Transformation of myeloid progenitors by MLL oncoproteins is dependent on Hoxa7 and Hoxa9. Genes & development. 2003;17(18):2298–307. doi: 10.1101/gad.1111603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeisig BB, Milne T, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Schreiner S, Martin ME, Fuchs U, et al. Hoxa9 and Meis1 are key targets for MLL-ENL-mediated cellular immortalization. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24(2):617–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.617-628.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo Z, Lin C, Shilatifard A. The super elongation complex (SEC) family in transcriptional control. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13(9):543–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krivtsov AV, Feng Z, Lemieux ME, Faber J, Vempati S, Sinha AU, et al. H3K79 methylation profiles define murine and human MLL-AF4 leukemias. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(5):355–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein EM, Tallman MS. Mixed lineage rearranged leukaemia: pathogenesis and targeting DOT1L. Current opinion in hematology. 2015;22(2):92–6. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Chen CW, Koche RP, Sinha AU, Deshpande AJ, Zhu N, Eng R, et al. DOT1L inhibits SIRT1-mediated epigenetic silencing to maintain leukemic gene expression in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Nat Med. 2015;21(4):335–43. doi: 10.1038/nm.3832. This study elucidated a mechanism through which DOT1L inhibitors show efficacy in treatment of MLL-rearranged leukemias. The study found that the histone deacetylase, SIRT1, establishes a heterochromatin-like state around MLL target genes following DOT1L inhibition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess JL. MLL: a histone methyltransferase disrupted in leukemia. Trends in molecular medicine. 2004;10(10):500–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhn MW, Hadler MJ, Daigle SR, Koche RP, Krivtsov AV, Olhava EJ, et al. MLL partial tandem duplication leukemia cells are sensitive to small molecule DOT1L inhibition. Haematologica. 2015;100(5):e190–3. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.115337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Borkin D, He S, Miao H, Kempinska K, Pollock J, Chase J, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the Menin-MLL interaction blocks progression of MLL leukemia in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):589–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.016. This study showed the efficacy of an orally available small-molecule inhibitor targeting the menin-MLL interaction for the treatment murine models of MLL-rearranged leukemias. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoelz A, Debler EW, Blobel G. The structure of the nuclear pore complex. Annual review of biochemistry. 2011;80:613–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-151030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dieppois G, Stutz F. Connecting the transcription site to the nuclear pore: a multi-tether process that regulates gene expression. Journal of cell science. 2010;123(Pt 12):1989–99. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gough SM, Slape CI, Aplan PD. NUP98 gene fusions and hematopoietic malignancies: common themes and new biologic insights. Blood. 2011;118(24):6247–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-328880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saw J, Curtis DJ, Hussey DJ, Dobrovic A, Aplan PD, Slape CI. The fusion partner specifies the oncogenic potential of NUP98 fusion proteins. Leuk Res. 2013;37(12):1668–73. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novak RL, Harper DP, Caudell D, Slape C, Beachy SH, Aplan PD. Gene expression profiling and candidate gene resequencing identifies pathways and mutations important for malignant transformation caused by leukemogenic fusion genes. Experimental hematology. 2012;40(12):1016–27. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Rooij JD, Hollink IH, Arentsen-Peters ST, van Galen JF, Berna Beverloo H, Baruchel A, et al. NUP98/JARID1A is a novel recurrent abnormality in pediatric acute megakaryoblastic leukemia with a distinct HOX gene expression pattern. Leukemia. 2013;27(12):2280–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollink IH, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Arentsen-Peters ST, Pratcorona M, Abbas S, Kuipers JE, et al. NUP98/NSD1 characterizes a novel poor prognostic group in acute myeloid leukemia with a distinct HOX gene expression pattern. Blood. 2011;118(13):3645–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-346643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Falini B, Sportoletti P, Martelli MP. Acute myeloid leukemia with mutated NPM1: diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic perspectives. Current opinion in oncology. 2009;21(6):573–81. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283313dfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Falini B, Nicoletti I, Martelli MF, Mecucci C. Acute myeloid leukemia carrying cytoplasmic/mutated nucleophosmin (NPMc+ AML): biologic and clinical features. Blood. 2007;109(3):874–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-012252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Falini B, Bolli N, Liso A, Martelli MP, Mannucci R, Pileri S, et al. Altered nucleophosmin transport in acute myeloid leukaemia with mutated NPM1: molecular basis and clinical implications. Leukemia. 2009;23(10):1731–43. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gurumurthy M, Tan CH, Ng R, Zeiger L, Lau J, Lee J, et al. Nucleophosmin interacts with HEXIM1 and regulates RNA polymerase II transcription. Journal of molecular biology. 2008;378(2):302–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monroe SC, Jo SY, Sanders DS, Basrur V, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Slany RK, et al. MLL-AF9 and MLL-ENL alter the dynamic association of transcriptional regulators with genes critical for leukemia. Experimental hematology. 2011;39(1):77–86. e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mueller D, Bach C, Zeisig D, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Monroe S, Sreekumar A, et al. A role for the MLL fusion partner ENL in transcriptional elongation and chromatin modification. Blood. 2007;110(13):4445–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khan SN, Jankowska AM, Mahfouz R, Dunbar AJ, Sugimoto Y, Hosono N, et al. Multiple mechanisms deregulate EZH2 and histone H3 lysine 27 epigenetic changes in myeloid malignancies. Leukemia. 2013;27(6):1301–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inoue D, Kitaura J, Togami K, Nishimura K, Enomoto Y, Uchida T, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes are induced by histone methylation-altering ASXL1 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4627–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI70739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bansal D, Scholl C, Frohling S, McDowell E, Lee BH, Dohner K, et al. Cdx4 dysregulates Hox gene expression and generates acute myeloid leukemia alone and in cooperation with Meis1a in a murine model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(45):16924–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604579103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rawat VP, Cusan M, Deshpande A, Hiddemann W, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Humphries RK, et al. Ectopic expression of the homeobox gene Cdx2 is the transforming event in a mouse model of t(12;13)(p13;q12) acute myeloid leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(3):817–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305555101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Speleman F, Cauwelier B, Dastugue N, Cools J, Verhasselt B, Poppe B, et al. A new recurrent inversion, inv(7)(p15q34), leads to transcriptional activation of HOXA10 and HOXA11 in a subset of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Leukemia. 2005;19(3):358–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camos M, Esteve J, Jares P, Colomer D, Rozman M, Villamor N, et al. Gene expression profiling of acute myeloid leukemia with translocation t(8;16)(p11;p13) and MYST3-CREBBP rearrangement reveals a distinctive signature with a specific pattern of HOX gene expression. Cancer Res. 2006;66(14):6947–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soulier J, Clappier E, Cayuela JM, Regnault A, Garcia-Peydro M, Dombret H, et al. HOXA genes are included in genetic and biologic networks defining human acute T-cell leukemia (T-ALL) Blood. 2005;106(1):274–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Y, Sitwala K, Bronstein J, Sanders D, Dandekar M, Collins C, et al. Identification and characterization of Hoxa9 binding sites in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2012;119(2):388–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polychronidou M, Lohmann I. Cell-type specific cis-regulatory networks: insights from Hox transcription factors. Fly. 2013;7(1):13–7. doi: 10.4161/fly.22939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sorge S, Ha N, Polychronidou M, Friedrich J, Bezdan D, Kaspar P, et al. The cis-regulatory code of Hox function in Drosophila. The EMBO journal. 2012;31(15):3323–33. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fung TK, Gandillet A, So CW. Selective treatment of mixed-lineage leukemia leukemic stem cells through targeting glycogen synthase kinase 3 and the canonical Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Current opinion in hematology. 2012;19(4):280–6. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283545615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Z, Iwasaki M, Ficara F, Lin C, Matheny C, Wong SH, et al. GSK-3 promotes conditional association of CREB and its coactivators with MEIS1 to facilitate HOX-mediated transcription and oncogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(6):597–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Z, Smith KS, Murphy M, Piloto O, Somervaille TC, Cleary ML. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 in MLL leukaemia maintenance and targeted therapy. Nature. 2008;455(7217):1205–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collins CT, Hess JL. Role of HOXA9 in leukemia: dysregulation, cofactors and essential targets. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rezsohazy R, Saurin AJ, Maurel-Zaffran C, Graba Y. Cellular and molecular insights into Hox protein action. Development. 2015;142(7):1212–27. doi: 10.1242/dev.109785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brayer KJ, Lynch VJ, Wagner GP. Evolution of a derived protein-protein interaction between HoxA11 and Foxo1a in mammals caused by changes in intramolecular regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(32):E414–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100990108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gehring WJ, Qian YQ, Billeter M, Furukubo-Tokunaga K, Schier AF, Resendez-Perez D, et al. Homeodomain-DNA recognition. Cell. 1994;78(2):211–23. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Busser BW, Gisselbrecht SS, Shokri L, Tansey TR, Gamble CE, Bulyk ML, et al. Contribution of distinct homeodomain DNA binding specificities to Drosophila embryonic mesodermal cell-specific gene expression programs. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e69385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lelli KM, Noro B, Mann RS. Variable motif utilization in homeotic selector (Hox)-cofactor complex formation controls specificity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(52):21122–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114118109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Breitinger C, Maethner E, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Slany RK. The homeodomain region controls the phenotype of HOX-induced murine leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(19):4018–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67•.Roychoudhury J, Clark JP, Gracia-Maldonado G, Unnisa Z, Wunderlich M, Link KA, et al. MEIS1 regulates an HLF-oxidative stress axis in MLL-fusion gene leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(16):2544–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599258. This study used an inducible Meis1 knockout mouse model together with an MLL-AF9 knockin mouse model to show that Meis1 is required for the maintenance of MLL-AF9 leukemias. This requirement was secondary to regulation direct regulation of HLF by Meis1 and subsequent maintenance of a low-oxidative state. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dardaei L, Penkov D, Mathiasen L, Bora P, Morelli MJ, Blasi F. Tumorigenesis by Meis1 overexpression is accompanied by a change of DNA target-sequence specificity which allows binding to the AP-1 element. Oncotarget. 2015;6(28):25175–87. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dardaei L, Longobardi E, Blasi F. Prep1 and Meis1 competition for Pbx1 binding regulates protein stability and tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(10):E896–905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321200111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dardaei L, Modica L, Iotti G, Blasi F. The deficiency of tumor suppressor prep1 accelerates the onset of meis1- hoxa9 leukemogenesis. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e96711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garcia-Cuellar MP, Steger J, Fuller E, Hetzner K, Slany RK. Pbx3 and Meis1 cooperate through multiple mechanisms to support Hox-induced murine leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100(7):905–13. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.124032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Z, Chen P, Su R, Hu C, Li Y, Elkahloun AG, et al. PBX3 and MEIS1 Cooperate in Hematopoietic Cells to Drive Acute Myeloid Leukemias Characterized by a Core Transcriptome of the MLL-Rearranged Disease. Cancer Res. 2016 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mann RS, Lelli KM, Joshi R. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Vol. 88. Academic Press; 2009. Chapter 3 Hox Specificity: Unique Roles for Cofactors and Collaborators; pp. 63–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Merabet S, Dard A. Tracking context-specific transcription factors regulating hox activity. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2014;243(1):16–23. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular cell. 2010;38(4):576–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou J, Wu J, Li B, Liu D, Yu J, Yan X, et al. PU.1 is essential for MLL leukemia partially via crosstalk with the MEIS/HOX pathway. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1436–48. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou J, Zhang X, Wang Y, Guan Y. PU.1 affects proliferation of the human acute myeloid leukemia U937 cell line by directly regulating MEIS1. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(3):1912–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ohlsson E, Hasemann MS, Willer A, Lauridsen FK, Rapin N, Jendholm J, et al. Initiation of MLL-rearranged AML is dependent on C/EBPalpha. J Exp Med. 2014;211(1):5–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ye M, Zhang H, Yang H, Koche R, Staber PB, Cusan M, et al. Hematopoietic Differentiation Is Required for Initiation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell stem cell. 2015;17(5):611–23. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steger J, Fuller E, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Hetzner K, Slany RK. Insulin-like growth factor 1 is a direct HOXA9 target important for hematopoietic transformation. Leukemia. 2015;29(4):901–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bei L, Shah C, Wang H, Huang W, Platanias LC, Eklund EA. Regulation of CDX4 gene transcription by HoxA9, HoxA10, the Mll-Ell oncogene and Shp2 during leukemogenesis. Oncogenesis. 2014;3:e135. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2014.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ortega S, Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cyclin D-dependent kinases, INK4 inhibitors and cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2002;1602(1):73–87. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith LL, Yeung J, Zeisig BB, Popov N, Huijbers I, Barnes J, et al. Functional crosstalk between Bmi1 and MLL/Hoxa9 axis in establishment of normal hematopoietic and leukemic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2011;8(6):649–62. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martin N, Popov N, Aguilo F, O’Loghlen A, Raguz S, Snijders AP, et al. Interplay between Homeobox proteins and Polycomb repressive complexes in p16INK(4)a regulation. The EMBO journal. 2013;32(7):982–95. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ueda K, Yoshimi A, Kagoya Y, Nishikawa S, Marquez VE, Nakagawa M, et al. Inhibition of histone methyltransferase EZH2 depletes leukemia stem cell of mixed lineage leukemia fusion leukemia through upregulation of p16. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(5):512–9. doi: 10.1111/cas.12386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Velu CS, Chaubey A, Phelan JD, Horman SR, Wunderlich M, Guzman ML, et al. Therapeutic antagonists of microRNAs deplete leukemia-initiating cell activity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(1):222–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI66005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]