SUMMARY

HIV-1 Tat activates viral transcription and limited Tat-transactivation correlates with latency establishment. We postulated a “block-and-lock” functional cure approach based on properties of the Tat-inhibitor didehydro-Cortistatin A (dCA). HIV-1 transcriptional inhibitors could block ongoing viremia during antiretroviral therapy (ART), locking the HIV promoter in persistent latency. We investigated this hypothesis in human CD4+T cells isolated from aviremic individuals. Combining dCA with ART accelerates HIV-1 suppression and prevents viral rebound after treatment interruption, even during strong cellular activation. We show that dCA mediates epigenetic silencing by increased nucleosomal occupancy at Nucleosome-1, restricting RNAPII recruitment to the HIV-1 promoter. The efficacy of dCA was studied in the bone marrow-liver-thymus (BLT) mouse model of HIV latency and persistence. Adding dCA to ART suppressed mice systemically reduces viral mRNA in tissues. Moreover, dCA significantly delays and reduces viral rebound levels upon treatment interruption. Altogether this work demonstrates the potential of “block-and-lock” cure strategies.

Keywords: HIV-1, Tat inhibitor, HIV latency, latent reservoir, didehydro-Cortistatin A, HIV-1 transcription, therapeutics, epigenetics, humanized mouse model, infected CD4+T cells, block and lock

IN BRIEF

Tat inhibitors are amenable to functional cure approaches, which aim at reducing residual viremia during ART and limit viral rebound during treatment interruption. Using Didehydro-Cortistatin A (dCA), Kessing et al. demonstrate the concept in human CD4+T cells from aviremic individuals and in the bone marrow-liver-thymus mouse model of HIV latency.

INTRODUCTION

HIV persists in latently infected CD4+ T cells in infected individuals even after prolonged periods on suppressive ART. Stable cellular reservoirs that harbor proviral DNA are thought to be the source of viremia upon ART interruption (Chun et al., 2008; Gunthard et al., 2001; Sogaard et al., 2015). Continuous viral production from viral reservoirs and transcriptional reactivation from latently infected cells are not affected by current antiretrovirals (ARVs), highlighting the need for novel approaches to achieve such an end (Chun et al., 2008; Gunthard et al., 2001; Sogaard et al., 2015).

The viral Tat protein binds HIV-1 mRNA and efficiently recruits the necessary transcriptional factors to the HIV promoter to initiate exponential viral transcription elongation (Dingwall et al., 1990; Dingwall et al., 1989; Kao et al., 1987; Toohey and Jones, 1989). Tat has no cellular homolog and is expressed early in the virus life cycle making it an ideal target for therapeutic intervention. Inhibitors of Tat have been highly sought after; but none is yet in the clinic. We identified didehydro-Cortistatin A (dCA) as a specific and potent Tat inhibitor (Mousseau et al., 2012). Over time dCA drives HIV-1 gene expression into a state of persistent latency, refractory to viral reactivation by the usual panel of latency reversal agents (LRAs) in cell-lines and primary CD4+ T cells isolated from infected individuals (Mousseau et al., 2015a). We postulated that this type of HIV-1 specific transcriptional inhibitors are amenable to a “block-and-lock” functional type approach to HIV-1 cure. Through increased epigenetic repression of the HIV promoter, Tat inhibitors could promote a durable state of latency, halting ongoing viral transcription during ART, blocking reactivation from latency, for example in situations of therapy non-compliance, or blocking “blips”, which are spontaneous reactivation events during ART, which may contribute to replenishment of the latent reservoir and continued persistence of HIV infection (Lorenzo-Redondo et al., 2016; Rong and Perelson, 2009).

The small number of latently infected cells in vivo has hindered studies of molecular mechanisms of HIV latency and reactivation. So far, no single primary cellular model alone accurately captures the response characteristics of latently infected T cells from patients, since these use clonal HIV strains, cultivate CD4+ T cells in cytokine cocktails that alter cell subset representation, or transform CD4+ T cells to prolong lifespan. We used a cell culture approach that allows expansion of large numbers of primary CD4+ T cells from successfully treated HIV infected donors in the presence of ART (Trautmann et al., 2002; Trautmann et al., 2005; Van de Griend et al., 1984). Under these conditions, primary CD4+ T cells carrying autologous HIV reservoir proliferate for two weeks, return to a resting state after three weeks, and can be maintained for up to 10 weeks. Cells stop producing HIV particles after three weeks, but virus can be reinduced either upon drug interruption or upon stimulation with LRAs, all while preserving their in vivo representation of the HIV reservoir. Using this approach, we explored the long-term effects of a prior exposure to dCA on natural or induced viral rebound during treatment discontinuation. We previously showed the lasting inhibitory activity of dCA over a short 6 day treatment interruption period (Mousseau et al., 2015a). Here we report that prior treatment with dCA inhibits viral rebound when treatment is interrupted for an extended 25 day period, even when cells were subjected to protein kinase C (PKC) activation or strong T cell receptor (TCR) signaling.

Repressive nucleosomes are associated with latent proviruses and upon reactivation from latency, rearrangement of the nucleosomal structure and loss of protection from Nucleosome-1 (Nuc-1) regions is observed (Rafati et al., 2011). To investigate the epigenetic profile at the HIV-1 promoter mediated by dCA, we took advantage of the previously described OM-10.1 HIV-1 latency model in which we had established a state of sustained latency by dCA (Mousseau et al., 2015a). We used MNase nucleosomal protection assays and ChIP to histone H3 and acetylated H3 to evaluate rearrangements of the nucleosomal structure. We observed higher nucleosomal occupancy (histone H3) at the Nuc-1 region, and small changes in H3 occupancy upon transcriptional activation in dCA treated cells. This result was supported by a drastic inhibition of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) recruitment to the HIV promoter and genome, and thus inhibition of transcriptional elongation.

To evaluate the in vivo efficacy of dCA we utilized the bone marrow/liver/thymus (BLT) mouse model of HIV-1 latency and persistence. Numerous studies have shown BLT mice recapitulate key features of HIV infection, pathogenesis, and latency (Cheng et al., 2017; Denton et al., 2014; Denton et al., 2012; Garcia, 2016; Melkus et al., 2006; Zhen et al., 2017). Administration of dCA to ART suppressed animals for a period of two weeks resulted in a general one log loss of viral RNA in tissues. Furthermore, co-dosing of dCA with ART for a period of four weeks significantly delayed viral rebound and reduced viral rebound levels after all treatments were interrupted. These results demonstrate the activity of dCA in an in vivo model of HIV-1 infection and represent strong proof-of-concept of the “block-and-lock” approach for the functional cure of HIV.

RESULTS

dCA accelerates HIV-1 suppression

HIV-infected memory CD4+ T cells remain in a resting state in the presence of ART, however, periodic activation of cells is believed to occur in subjects on ART contributing to the basal low levels of viremia. In cell models of latency, virus can be reactivated either upon ART removal or upon cellular stimulation with HIV LRAs. To study the ability of dCA to limit viral transcription in these contexts, we used a previously established protocol to maintain primary CD4+ T cells from infected individuals for up to 10 weeks in culture, while preserving their characteristic representation of the HIV reservoir (Kessing et al., 2017; Mousseau et al., 2015a).

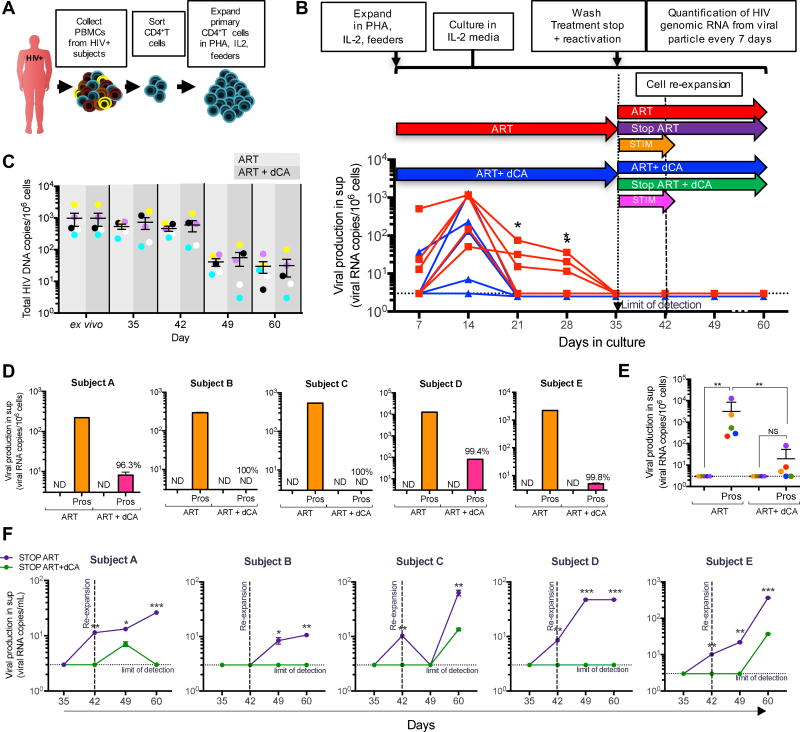

Using this model, we previously reported dCA’s block of viral rebound for a six days period after ART interruption. The question remained though, whether this inhibitory activity was long lasting and whether it could withstand strong cellular stimulation. Here, we assessed the ability of dCA to promote transcriptional suppression for a period of 25 days while receiving strong T cell activation seven days post treatment interruption. As such, PBMCs from five HIV-infected subjects on suppressive ART for at least three years were collected and CD4+ T cells were isolated and expanded in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL), PHA (1 µg/mL) and “feeder cells” (Fig. 1A). Cells were then kept in culture for 60 days in medium containing IL-2 (20 U/mL), ART (efavirenz, zidovudine, raltegravir) and with or without 50 nM dCA (“ART” or “ART + dCA” conditions) (Fig. 1B). Viral particle genomic RNA in the culture supernatant was quantified by ultrasensitive RT-qPCR every seven days. After 28 days of treatment, virus production from all five subjects’ cells exposed to dCA was below the limit of detection and significantly inhibited as compared with ART alone (p=0.0238) (Fig. 1B). At day 35, supernatant HIV RNA levels from all subjects’ cells were below detection and remained so until day 60 in both treatment groups. The amount of total integrated HIV DNA was measured over time. As expected due to the presence of ART in both conditions, no significant differences in total HIV DNA content were observed between the cells immediately after isolation from the patients blood, labelled ex vivo, and the expanded cells in ART or ART plus dCA, up to day 42 (Fig. 1C). As such, viral mRNA production in dCA treated samples is the consequence of Tat transcriptional inhibition and not a reduction in proviral content. Moreover, since the total HIV DNA content between ex vivo cells and expanded ones is similar, the representation of each individual’s viral reservoir is not being lost. However, at day 49 we observed a general loss of proviral DNA content following the cellular expansion performed at day 42. This is possibly due to some increased cytopathic effects associated with the age of the cells, reflecting some of the limitations of primary models. Nevertheless, the proviral content between the ART and the ART with dCA treated cells remains similar, permiting comparisons in viral RNA expression.

Figure 1. Addition of dCA to ART promotes rapid HIV-1 suppression from primary human CD4+ T cells isolated from infected individuals and inhibits viral rebound during reactivation and treatment interruption.

A. PBMCs are extracted from successfully treated aviremic HIV-infected individuals (at least 3 years on ART). CD4+ T cells are isolated and expanded in PHA, IL-2, feeder cells (irradiated PBMCs from 3 healthy donors). B. Expanded primary human CD4+ T cells from 5 HIV-infected individuals were kept on IL-2 alone and treated with a cocktail of ART with or without 50 nM dCA. Viral RNA levels in the supernatant of ART and ART+dCA treated cells measured every 7 days. After 35 days in culture viral RNA production in the supernatant was below the detection limit (*p<0.05). C. Total HIV DNA was determined up to 60 days in cells treated with ART or ART+dCA. Limit of detection for the qPCR is 3 viral copies per million cells and error bars represent standard error. D. On day 35 cells were stimulated overnight with 1 µM prostratin without ART or dCA. Viral production in supernatant quantified by RT-qPCR. E. Aggregate plot of data from D. Significant decrease (**p<0.01) in viral rebound after stimulation in dCA treated compared to ART alone. F. Treatment interruption does not result in immediate viral rebound even during strong cellular activation. On day 35, all drugs (ART and dCA) were removed and viral output in the supernatant quantified for the next 25 days by RT-qPCR. Cells were re-expanded with PHA, IL-2 and feeder cells at day 42 to maintain cell cultures and provide a stimulation. Results show viral RNA levels in the supernatant for each individual sample. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. ND, not detected; sup, supernatant.

dCA limits viral reactivation after stimulation

To determine the ability of dCA to effectively block viral rebound after strong NF-κB activation, cells were treated with the PKC activator prostratin, in the absence of any treatment (Fig. 1B, orange and pink arrows), at day 35 when viral RNA production was below detection in all groups. HIV RNA in the supernatant was measured by RT-qPCR 24 hours later. When ART was removed followed by stimulation, viral rebound was immediately observed in all subjects’ cells (Fig. 1D, orange bars). In contrast, upon dCA and ART removal followed by stimulation, viral reactivation was inhibited by 96.3%, 100%, 100%, 99.4%, and 99.8% in cells from subjects A, B, C, D and E respectively, with an overall average inhibition of 99% for all five subjects after 24 hours (Fig. 1D, pink bars). Upon prostratin treatment, viral reactivation in cells with prior exposure to dCA was significantly reduced as compared to treated with ART alone (p=0.008), and no significant differences were observed in viral reactivation in dCA treated cells before or after stimulation (Fig. 1E). These results demonstrate that prior treatment with dCA (for 35 days) results in repression of viral promoter activity, a potentially effective treatment for preventing moments of viral reactivation under suppressive ART and replenishment of reservoir in vivo.

dCA treatment prevents viral rebound after therapy interruption and strongly reduces viral rebound after mitogenic stimulation

ART interruption in HIV suppressed individuals, in all but exceptional cases, results in viral rebound within weeks. To determine whether prior treatment with dCA could have lasting repressive transcriptional activity post treatment interruption, we stopped ART or ART and dCA at day 35, and followed viral replication in the supernatant by RT-qPCR for another 25 days (up to day 60) (Fig. 1F, Fig. 1B purple and green arrows). Cells remaining on treatment showed no viral production after day 35 (Fig. 1B, red and blue arrows). Seven days after treatment cessation viral rebound was readily observed in 4 of the 5 subjects’ cells treated with ART alone. No rebound was observed in CD4+ T cells previously cultured in the presence of ART and dCA from all five subjects by day 7. Viral rebound was seen in all 5 ART treated subjects’ cells 25 days post treatment interruption and only 2 rebounded minimally in cells previously treated with ART and dCA (Fig. 1F). To assess whether dCA mediated transcriptional suppression, could withstand events of viral reactivation even in the absence of treatment, cells were activated at day 42 with PHA, IL-2 and feeder cells. In all ART treated cells (no dCA), viral production continuously increased over time, while it was drastically inhibited in cells treated with ART and dCA. Our results clearly demonstrate that combining dCA with ART can potently inhibit viral reactivation from latency after treatment cessation, even during strong cellular activation, suggesting that dCA contributes to long lasting repression of the HIV promoter.

dCA does not alter T cell activation levels

The phenotype of the CD4+ T cells treated with ART or ART and dCA was monitored weekly by flow cytometry up to day 49 to quantify the number of live cells and to ensure re-establishment of a resting state after expansion. We used CD38+ as an activation marker, and CD127+ for quiescence (Supp. Fig. 1A). Cells reached peak activation by day 14 after initial expansion, followed by a decrease in activation and return to a resting state. As expected CD38+ expression increased and CD127+ (IL-7 receptor) decreased during peak activation. Cells were re-expanded on day 42 and expression of activation markers increased accordingly. Additionally, viability of the cultures was measured by trypan blue staining overtime during treatment and after treatment interruption (Supp. Fig. 1B) and DNA content measured before and after stimulation to insure there was no loss or variation of the number of infected cells between treatment groups (Supp. Fig. 1C). Gene expression was also monitored using a Biomark Assay of 52 genes related to various signaling pathways including T cell activation, cell cycle, apoptosis, transcription factors, and TCR signaling (Supp. Fig. 2). No statistical significant differences were observed overtime between the three individual’s cell samples and between treatments. Even if not significant, we observed GATA3 and CCR7 genes to be the most altered between ART and ART+dCA samples at day 14. It has been reported that GATA3 and CCR7 expression is inversely correlated with HIV expression (Kessing et al., 2017; Ramirez et al., 2014; Rueda et al., 2012). As such, in future work we will further investigate these genes during the expansion of the cells in vitro.

Collectively, no significant differences in phenotype, or gene expression were observed in cells treated with ART compared to ART and dCA over time. Our results suggest that long-term treatment of primary human CD4+ T cells in vitro with dCA establishes a state of sustained latency that nearly or completely hinders the provirus capacity for reactivation after treatment removal, without significantly affecting viability, phenotype, or cellular gene expression patterns.

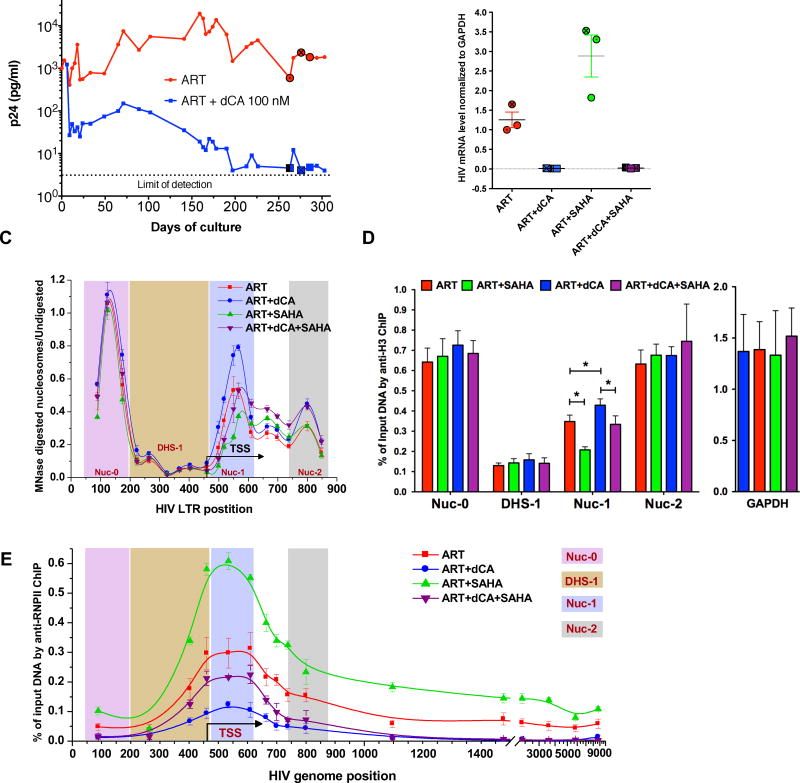

Changes in chromatin signature and RNAPII recruitment after dCA treatment

Differential nucleosome organization in the HIV-1 LTR correlates with transcription from proviral genomes in latently infected cells (Rafati et al., 2011). Our previous results suggested that dCA causes effects that promoted organization of repressive chromatin structure that prevents strongly/rapidly reactivating transcription of latent provirus. To examine the molecular correlates that controlled transcription from the HIV-1 promoter in response to long term dCA treatment, we assayed histone density and chromatin accessibility, as well as, RNA Pol II recruitment at the HIV-1 provirus using MNase digestion (Rafati et al., 2011), and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), in the previously described OM-10.1 HIV-1 latency model (Mousseau et al., 2015a). OM-10.1 cells contain a single copy of a fully replicative provirus and were treated with ART, or ART and dCA, until viral production was almost-undetectable by p24 ELISA in dCA treated samples (Fig. 2A). On days 263, 276, and 286 (shown as circle and square in Fig. 2A) HIV-1 transcription was stimulated using the HDAC inhibitor SAHA (2.5 µM) for 8 hours in the presence of treatment and cell-associated HIV-1 RNA was measured by qPCR (Fig. 2B). As expected, in OM-10.1 cells treated with ART and dCA we observed 98% less viral rebound after SAHA treatment compared to cells treated with ART alone (Fig. 2B). At these time points, unstimulated and SAHA-stimulated cells from each treatment condition were fixed with formaldehyde, nuclei were prepared, and treated with MNase under conditions to generate mono-nucleosomes. Under unstimulated conditions in OM10.1 cells, we detected MNase-protected regions at the 5’ end of the LTR (Nuc-0), and in two regions immediately downstream of the transcription start sites (TSS), Nuc-1 and Nuc-2, as well as an MNase-sensitive region at the DNaseI-hypersensitive region (DHS-1) immediately upstream of the TSS (Fig. 2C). MNase protection, and most likely nucleosomal occupancy, at Nuc-0 or Nuc-2 was similar in resting cells treated with ART only, compared to those treated with ART and dCA. However, there was significantly stronger MNase protection at Nuc-1 in cells treated with both ART and dCA, suggesting increased nucleosome occupancy at this location in the presence of dCA (Fig. 2C). After SAHA treatment, MNase protection decreased at Nuc-1 in both ART or ART and dCA treated groups (Fig. 2C). However, occupancy at Nuc-1 in cells treated with both ART and dCA was comparable to that in unstimulated cells treated with ART alone. This suggests that a combination of dCA and ART decreases chromatin accessibility at the LTR, reducing transcriptional competence of latent HIV-1 genomes under conditions that promote reactivation.

Figure 2. Characterization of chromatin structure and RNAPII recruitment to the HIV genome after long term treatment with dCA using the OM10.1 latency model.

A. dCA inhibits viral production in the OM-10.1 cell line to almost-undetectable levels. OM-10.1 cells were split and treated on average every 3 days in the presence of ARVs with or without dCA (100 nM). Capsid production was quantified via p24 ELISA. Data are representative of four independent experiments. B. On days 263, 276 and 286 cells treated with ARVs and ARVs+dCA (100 nM) were stimulated with SAHA (2.5 µM) for 8 hours (highlighted with ⦿/☒ in panel A). cDNAs prepared from total RNA quantified by RT-qPCR with Nef region primers. Results were normalized as number of viral mRNA copies per GAPDH mRNA. Viral mRNA generated in the ARVs control was set to 100%, error bars represent the standard deviations of 3 independent experiments. C. The chromatin structure of the HIV LTR assessed by Micrococcal nuclease (MNase) protection assay. The chromatin profile of cell samples from B was determined by normalizing the amount of the MNase digested PCR product to that of the undigested product using the ΔC(t) method (y-axis), which is plotted against the midpoint of the corresponding PCR amplicon (x-axis). The X-axis represents base pairs units with 0 as the start of HIV LTR. Error bars represent the standard deviations of 3 independent experiments. D. H3 ChIP of cell samples from B. The promoter of GAPDH was used as a reference. The results are presented as percent immunoprecipitated DNA over input. Data are average of 3 independent experiments, and error bars represent the standard deviations of 3 experiments for each primer set. Statistical significance was determined using paired t-test, *p<0.05. E. Distribution of RNAPII on the HIV genome. ChIP to RNAPII was performed using cells samples from panel B. Data are average of 3 independent experiments, and error bars represent the standard deviations of 3 experiments for each primer set.

To determine whether increased MNase-protection at the Nuc-1 region was likely due to increased nucleosome occupancy during treatment with dCA and ART, an antibody specific for total histone H3 was used in ChIP assays (Fig. 2D). A significant increase in H3 at Nuc-1 region was apparent in ART and dCA treated cells, compared to ART alone, whereas we did not observe differences in H3 occupancy at Nuc-0, DHS-1, and Nuc-2 between any of the samples (Fig. 2D, red versus blue bars). Moreover, H3 occupancy at the Nuc-1 region in ART and dCA treated samples after SAHA activation was comparable to that observed in ART treated cells prior to activation (Fig. 2D, red versus purple bars). Thus, although SAHA treatment reduced H3 occupancy at the Nuc-1 region in both SAHA stimulated samples, the absolute amount of H3 coverage remained high in dCA and ART treated cells. These results provide evidence that increased MNase-protection at the Nuc-1 region in dCA-treated cells is the result of increased nucleosome occupancy.

Next we investigated the recruitment of RNAPII to the HIV provirus using ChIP (Fig. 2E). In cells treated with either ART alone, or ART and dCA, there was a peak of RNAPII near the HIV-1 promoter, but this peak was significantly lower in cells treated with dCA and ART (Fig. 2E, compare red and blue lines). Thus, fewer HIV-1 proviruses have RNA Pol II recruited to their TSS in the presence of dCA. Furthermore, cells treated with both ART and dCA lacked detectable RNA Pol II density within the transcribed portion of the HIV-1 genome, whereas cells treated with only ART exhibited substantial RNA Pol II signal. In the additional presence of SAHA, cells treated with either ART alone, or ART and dCA, both increased RNAPII recruitment to the promoter (Fig. 2E). However, recruitment in ART and dCA treated samples after SAHA activation was lower to that observed in ART treated cells prior to activation. Moreover, there was a striking absence of RNA Pol II within the transcribed sequences of HIV-1 in cells treated with dCA and ART, compared to cells treated with ART only. Taken together, our results indicate that extended inhibition of Tat activity with dCA treatment promotes increased nucleosome occupancy in the Nuc-1 region and this precludes RNAPII recruitment to the LTR and also reduces its elongation potential upon stimuli that normally induce HIV-1 transcription.

Impact of dCA on tissue viremia in HIV-infected, ART-suppressed BLT humanized mice

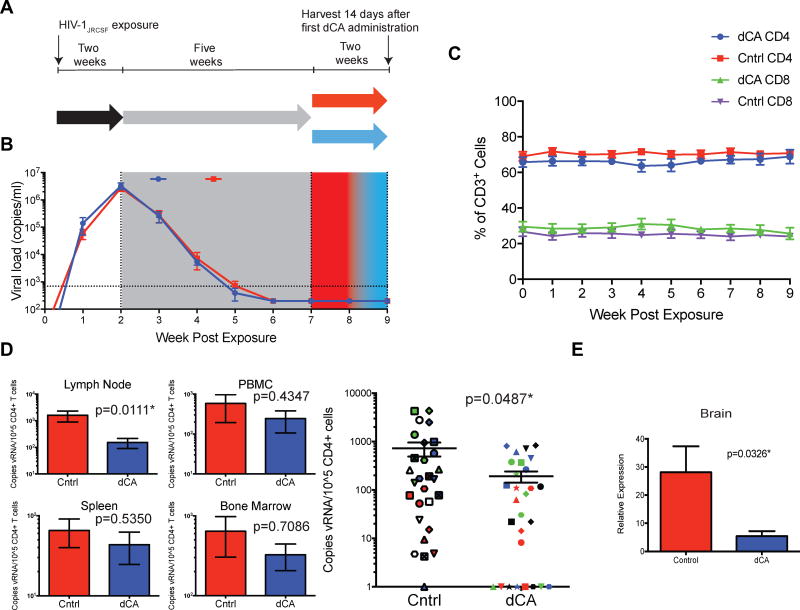

We explored the activity of dCA in vivo by asking whether dCA administration would impact the levels of cell-associated viral RNA that persist in lymphoid tissues despite ART (Denton et al., 2014). We first determined that dCA had acceptable pharmacokinetic properties in mice receiving once-daily intraperitoneal dosing at 0.50 mg/kg with no loss of body weight or adverse effects in blood biochemistry (data not shown). Next, BLT humanized mice (n=14) were infected with HIV-1JRCSF and bled weekly for the duration of the experiment to monitor plasma viral load and human CD4+ T cells counts (Fig. 3A). Two weeks following virus exposure, systemic infection was confirmed and ART was initiated. Five weeks after the initiation of ART, vehicle or dCA (0.5 mg/kg) was administered for 14 days (n=7 in each group). The copies of viral RNA per mL of plasma remained below our level of detection in all animals and the levels of human CD4+ T cell levels in peripheral blood were not impacted by dCA (Fig. 3B–C; Supp. Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Impact of dCA on ART mediated suppression of viremia and residual viral RNA expression in tissues of humanized mice.

A. Diagram outlining the experimental design and highlighting the two different treatments (red and blue). B. Aggregate plot of all HIV-infected BLT humanized mice receiving dCA (blue, n=7) or vehicle (red, n=7) in addition to ART shows similar kinetics of viral suppression and no increases in plasma viral load as a result of dCA treatment. C. dCA administration does not affect plasmas viral load levels or the levels of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood. D. (Left) Residual HIV-1 RNA levels in spleens, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from control (red) and dCA treated mice (blue). (Right) Reductions in viral RNA for all individual tissues from all animals are graphed together. Each mouse was assigned a different shape, and tissues are coded by color: spleen-red, bone marrow-blue, lymph node-green, PBMC-black. E. Residual HIV-1 RNA levels in brain tissue from control and dCA treated animals. HIV RNA levels were normalized to the levels of TATA box binding protein RNA. Error bars in D and E indicate standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann-Whitney U test.

At the end of this period, mice were sacrificed and tissues harvested for analysis of viral RNA and human cells. Viral RNA levels were quantified by RT-qPCR and normalized to the number of human CD4+ T cell in spleens, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and PBMCs (Fig. 3D, left). In the lymph node, the mean number of copies of viral RNA per 105 CD4+ T cells was 10.5-fold lower in dCA treated mice compared to control mice (153.2 ± 63.28 vs 1614 ± 714.5) and this difference was statistically significant (P=0.0111). The reductions in RNA levels observed in all other lymphoid tissues were not statistically significant. However, when these four lymphoid tissues are analyzed in aggregate, we found a statistically significant difference in the number of copies of viral RNA in dCA treated mice compared to controls (p=0.0487) (Fig. 3D, right). The mean number of copies of viral RNA per 105 CD4+ T cells in these combined tissues in dCA treated BLT mice was 191.7 ± 49.93 while it was 725.6 ± 233.9 in the same tissues from control mice, indicating a 3.8-fold lower mean level of viral RNA in mice treated for 14 days with dCA. Analysis of HIV RNA levels in the brains obtained from mice treated with dCA also show a significant (~7-fold) decrease when compared to control mice (p=0.0326). In sumary, these results indicate that dCA treatment does not negatively impact suppression of HIV-1 infection by ART or alter levels of human CD4+ T cells in BLT mice. Furthermore, there is a clear trend indicating lower levels of viral gene expression in dCA treated, HIV infected, ART suppressed humanized mice compared to control mice treated with a saline control.

Impact of dCA treatment on viral rebound following therapy interruption

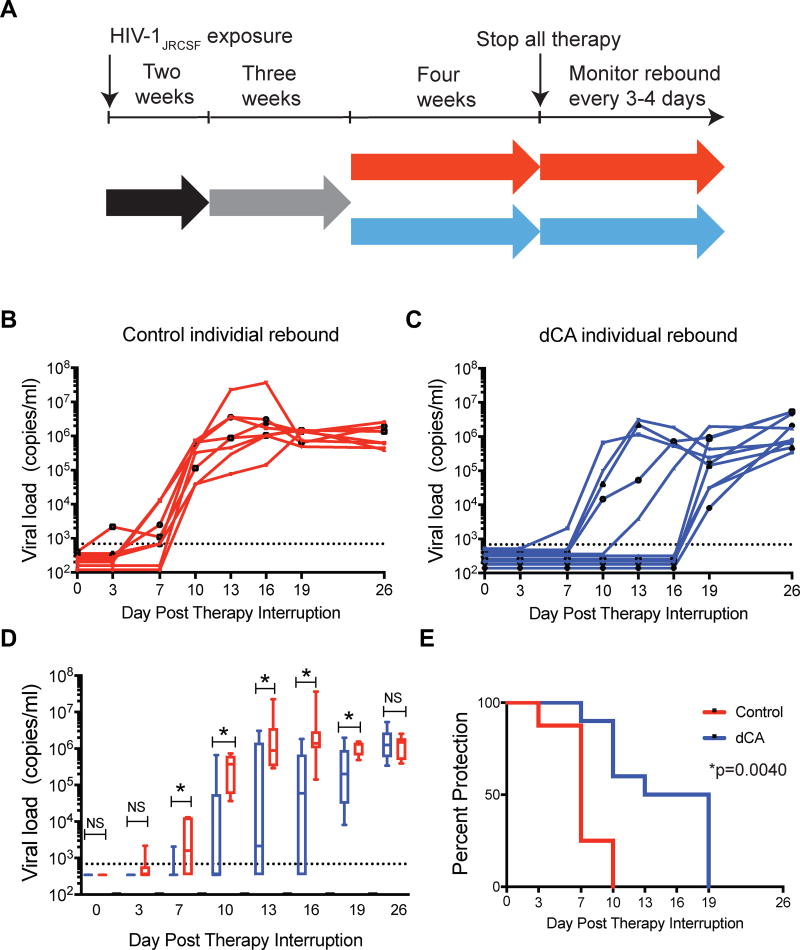

Next, we asked whether dCA treatment would affect the kinetics of viral rebound upon therapy interruption. As such, we infected BLT humanized mice with HIV-1JRCSF and infection was confirmed two-weeks post-exposure at which point therapy was initiated (Fig. 4A). After three weeks of ART, either dCA (n=10) or vehicle (n=8) treatment was combined to ART. At the end of four weeks of co-administration, both dCA and ART treatment were discontinued and plasma viremia was monitored overtime. During treatment, there were no discernible differences in the levels of human CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood between the mice receiving ART plus dCA and those receiving ART plus vehicle (Supp. Fig. 4).

Figure 4. dCA treatment results in a delay in rebound viremia in HIV-1 infected, suppressed BLT humanized mice following therapy interruption.

A. Diagram outlining the experimental design and experimental groups receiving ART+dCA (blue) or ART alone (red). B. Rebound viremia following therapy interruption (day 0) in individual HIV infected ART treated mice administered vehicle, or C. Rebound viremia following therapy interruption (day 0) in individual HIV-infected, ART-treated mice that were administered dCA. D. Comparison of the median viral load of mice treated with vehicle and with dCA following therapy interruption. In these plots, the boxes extend from the first to the third quartiles, enclosing the middle 50% of the data. The middle line within each box indicates the median of the data. Blue boxes indicate dCA treated mice and red boxes indicate control mice. * statistical significant differences between control and dCA treated mice as determined by the Mann-Whitney U-test. E. Time to event (Kaplan-Meier) plot demonstrating the significant delay in viral rebound observed in animals treated with dCA (p=0.0040, exact rank test).

Control mice began to exhibit rebound viremia as early as three days post therapy interruption and by day ten all eight control mice showed rebound viremia (Fig. 4B and Fig. 4C). In stark contrast, none of the ten mice that received dCA treatment exhibited rebound viremia at day three and only one had detectable levels of plasma viremia by day seven. By day ten, all eight control mice continued to show high levels of plasma viremia. In contrast, virus was still below detection in 6 of 10 of the dCA treated mice. Indeed, at days 13 and 16 no additional dCA treated mice exhibited rebound viremia. It was not until day 19 post therapy interruption that viral rebound was first detected in the remaining five dCA treated mice (Fig. 4B and Fig. 4C).

When the means of the rebound viremia in control mice are compared to those of the dCA treated mice, there are statistically significant differences between the two groups beginning at day seven and for each time point thereafter (Fig. 4D and Table 1) (Mann-Whitney U-test). At day seven, the difference in mean viremia between control and dCA treated mice was 1085 copies of viral RNA/ml of plasma (1500 copies of viral RNA/ml in control vs 410 in dCA treated mice, p=0.0091). At day ten, the mean viral load of the control mice was greater than 2×105 compared to only 3×103 copies of viral RNA/ml plasma in the dCA treated mice. This is a difference of greater than 2×105 copies of viral RNA/ml plasma (p=0.0067). The difference in the means of viral loads at day 13 was greater that 5×105 copies of viral RNA/ml plasma (p=0.0243). The largest difference between the viral loads of control mice and dCA treated mice (120-fold, p=0.0029) was noted at day 16 post therapy interruption. Even at day 19 post therapy interruption a five-fold difference in plasma viral loads was observed (p=0.0198) (Fig. 4D and Table 1). It was not until day 26 post therapy interruption that the mean viral loads between the two groups were no longer different (p=0.7796) (Fig. 4D and Table 1). Time to event statistical analysis demonstrates that the differences in the time to rebound for all the mice in the dCA treatment and control groups is significantly different (p=0.0040, exact rank test) (Fig. 4E). Together, these results demonstrate that dCA treatment can significantly delay and reduce viral rebound in HIV-infected, ART-suppressed humanized mice.

Table 1.

Viral load analysis following therapy interruption in HIV-1 infected ART suppressed BLT humanized mice receiving vehicle (controls) or dCA.

| Days Post Therapy Interruption |

Viral Load dCA Treated Mice |

Viral Load Control Mice |

Difference in Viral Load Between Control and dCA Treated Mice |

Fold Difference in Viral Load Between Control and dCA Treated Mice |

Mann- Whitney p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 344 | 344 | 0 | 0 | >0.9999 |

| 3 | 344 | 433 | 90 | 1 | 0.4444 |

| 7 | 411 | 1496 | 1085 | 4 | 0.0091 |

| 10 | 3028 | 222705 | 219677 | 74 | 0.0067 |

| 13 | 9772 | 565468 | 555696 | 58 | 0.0243 |

| 16 | 13865 | 1722890 | 1709025 | 125 | 0.0029 |

| 19 | 177190 | 1023500 | 846310 | 6 | 0.0198 |

| 26 | 1254213 | 1489199 | 234987 | 1 | 0.7796 |

DISCUSSION

Using two state of the art models of HIV-1 latency and persistence, primary CD4+ T cells isolated from infected ART suppressed individuals and BLT humanized mice, our findings provide evidence that the Tat inhibitor, dCA, can potently inhibit residual levels of HIV viral transcription during suppressive ART and block viral reactivation upon stimulation or during treatment interruption.

The small number of latently infected cells in patients (~1 in 106 CD4+ T cells) has rendered difficult the studies of HIV latency and reactivation (Pierson et al., 2000). To overcome this limitation, we utilized a method where memory CD4+ T cells are isolated from aviremic HIV-infected subjects and expanded in vitro in the presence of ART, feeder cells, IL-2, and PHA (Trautmann et al., 2002; Trautmann et al., 2005; Van de Griend et al., 1984). In this primary cell system, using CD4+ T cells from five infected, aviremic individuals, we answered several questions regarding the long-term in vitro activity of dCA: 1) Does dCA have an additive activity to ART in reducing viral replication during cellular expansion? 2) Does the pretreatment of cells with dCA result in long-term suppression of the HIV promoter after treatment interruption, even if cells are subjected to strong cellular activation? Our results demonstrate the ability of dCA to accelerate the inhibition of viral production during cellular expansion as compared to treatment with ART alone (Fig. 1B), demonstrating the additive activity of dCA and supporting the notion that adding Tat inhibitors to front-line treatment might lead to faster suppression and potentially reduce the size of the established reservoir. Previous studies in which infected individuals received ART within a few weeks of contracting HIV found that this early treatment reduced total HIV DNA levels by 20-fold after a couple of weeks and 316-fold reduction after three years (Ananworanich et al., 2016; Ananworanich et al., 2015). Smaller reservoir sizes have also been linked to delays in viral load rebound after ART cessation (Hatzakis et al., 2004). For instance, this was observed in the case of the Mississippi baby (Persaud et al., 2013), the VISCONTI cohort (Hatzakis et al., 2004; Saez-Cirion et al., 2013) and French teenager (Frange et al., 2016).

Using primary cells from patients we demonstrated the ability of dCA to inhibit reactivation from latency, exemplified by drastically impaired viral rebound upon cellular stimulation with the PKC activator, prostratin, post ART and dCA treatment interruption (Fig. 1D–F). The effects of dCA are solely correlated to inhibition of viral transcription, since the total HIV DNA content remained unchanged throughout the study (Fig. 1C and Supp. Fig. 1C). It is important to insure in primary latency models the maintenance of the representation of the individuals’ viral reservoir over time, and that there is no selection of a population of cells that is non-responsive to reactivating stimuli. In our model we successfully demonstrated that the total proviral content before and after expansion was similar, and that we had not lost cells with the ability to reactivate the virus, as observed in similar models (Bui et al., 2017).

The lasting activity of dCA to mediate long-term repression of the HIV promoter was shown by demonstrating its ability to limit viral rebound after treatment cessation. ART is known to successfully reduce viral replication in patients, but if ART is interrupted HIV rebounds within weeks (Bennett et al., 2008; Davey et al., 1999). Using our primary cell system to recapitulate what is seen in patients, we demonstrated viral rebound within a week after treatment cessation in cells previously treated with ART alone for 35 days (Fig. 1F). However, previous treatment with dCA drastically reduced viral rebound in primary human CD4+ T cells after treatment cessation up to 25 days. Most importantly, when an extremely strong activation of the cells was performed using PHA, IL-2 and feeder cells, seven days post treatment interruption, no viral rebound was observed in the cells pre-treated with dCA.

Using the previously described OM10.1 cell line model of latency, we present evidence that dCA treatment results in a less permissive chromatin environment downstream of the TSS at Nuc-1 (Fig. 2). This correlated with decreased RNAPII recruitment and elongation. Upon activation of the cells with a latency reversing agent such as SAHA, we observed a decrease in nucleosome occupancy at Nuc-1 and some increase in RNAPII recruitment. However, recruited RNAPII does not efficiently elongate to transcribe the full length genome, since this function is promoted by Tat. As such, HIV-1 mRNA transcription is drastically impaired even after stimulation, supporting previous studies that show that Tat is the master regulator of latency and the key switch to turn on/off transcription independently of cell activation status (Razooky et al., 2015). Collectively, our results suggest that dCA reduces HIV-1 transcriptional activity compared to that which occurs under ART, promotes silencing of its promoter, and reduces its potential for reactivation. Future studies will investigate how recruitment of specific cellular activators and repressors to the HIV-1 LTR/promoter regulate its epigenetic configurations and transcriptional potential in response to prolonged dCA treatment.

The efficacy of dCA in vivo was shown using the BLT humanized mouse model validated for the analysis of HIV latency and persistence (Cheng et al., 2017; Denton et al., 2014; Denton et al., 2012; Garcia, 2016; Melkus et al., 2006; Zhen et al., 2017). Humanized BLT mice are an excellent model for evaluating HIV latency as they allow us to track HIV infection of human cells, in the context of a complex substrate that includes mature T and B lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells, as they infiltrate all organs and tissues in a living organism. Treatment with dCA reduced the levels of cell associated viral RNA in lymphoid tissues. Most striking was the 10.5-fold reduction in the lymph node (Fig. 3D). When analyzing all tissues combined we observed an approximate 1 log reduction in systemic levels of viral RNA in the period of just two weeks (Fig. 3D). Also impressive was the strong reduction in HIV RNA levels observed in the brains of dCA treated mice. HIV infection of the brain has been long consider of paramount importance in HIV cure research. Recent reports indicate that the use of kick and kill approaches to HIV eradication might have negative concequences as they might increase immune activation which could result in a harmful inflammatory response (Gama et al., 2017). Our results indicate that dCA and the lock and block approach to HIV cure might provide an important alternative of great significance. Given the feedback nature of the Tat-TAR activity, and as previously shown (Mousseau et al., 2015a), the longer the treatment with dCA the better the outcome as the promoter becomes increasingly silenced (Fig. 2). This argues that we can only expect better outcomes with longer treatment periods with dCA. These results also support our findings in vitro in which dCA accelerated entry of HIV into latency (Fig. 1B).

The key experiment assessing the long-lasting activity of dCA in repressing the HIV promoter transcription was performed in suppressed mice after a four week coadministration of ART with dCA followed by analytical treatment interruption (Fig. 4). Virus was readily detected in the plasma of all mice receiving ART within seven days after discontinuation of treatment. Impressively, in BLT mice previously treated with ART and dCA, viral rebound was significantly delayed up to 19-days post treatment interruption. It is worth noting that in half of the dCA treated mice, virus was below our level of detection until day 16 post treatment interruption only rebounding at day 19. In a general manner dCA offered an impressive nine-day protection as compared to ART alone. Future studies will investigate the relationship between the period of treatment with dCA to time to viral rebound. We speculate that over time (in combination or not with other inhibitors) transcriptional repression could be pushed passed a certain threshold where viral reactivation from latency is extremely difficult to overcome (Weinberger and Weinberger, 2013; Weinberger et al., 2008), blocking-and-locking HIV into sustained latency. Our results are the in vivo proof-of-principle for a “block-and-lock” approach for a functional cure of HIV. An additional benefit of HIV transcriptional inhibitors whether they target Tat or TAR, or other factors such as CDK9 or Cyclin T1 (reviewed in (Mousseau et al., 2015b) is their ability to reduce morbidities associated with persistent levels of immune activation caused by low-level ongoing virus replication in subjects on suppressive ART (Hunt, 2010). Although controversial, a potential contributor to the sustained maintenance of the latent reservoir is viral replication reflected in “blips” observed in plasma that could be reseeding the reservoir even in the presence of ART (Chun et al., 2005; Jones and Perelson, 2007; Ramratnam et al., 2004). Additionally, therapy non-compliance or short breaks in therapy can also result in viral production and in reservoir replenishment. Including dCA to ART regimens could potentially inhibit reservoir replenishment during these situations.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that in the setting of full HIV suppression, dCA 1) reduces cell-associated viral RNA systemically, 2) significantly delays viral rebound upon treatment interruption and 3) reduces viral rebound levels by several orders of magnitude. This is the first time pharmacological inhibition of viral rebound after treatment interruption has been shown in an in vivo model of HIV infection. These results strongly support the rational for the inclusion of specific HIV transcriptional inhibitors in eradication strategies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Subject samples

Primary human CD4+ T cells were collected from five HIV-seropositive subjects on stable suppressive ART for at least three years. All subjects signed informed consent approved by the CR-CHUM hospital (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) review boards. All patients underwent leukapheresis to collect large numbers of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

Generation of expanded primary human CD4+ T cells

Primary CD4+ T cells from five successfully treated donors were expanded as previously described (Mousseau et al., 2015a). Briefly, 50×106 PBMCs were thawed and sorted CD45RA−, CD27+, CD4+ T cells were expanded with 1 µg/mL of PHA (Sigma Aldrich), 100 U/mL of IL-2 (Roche) and irradiated feeder PBMCs (OneBlood). Cells were then kept on either ART alone (100 nM Efavirenz, 180 nM Zidovudine, 200 nM Raltegravir) or ART and 50 nM dCA (kindly provided by Dr. Phil Baran, Scripps La Jolla) in medium supplemented with human serum and 20 U/mL IL-2. ART reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. For stimulation experiments, 1 million cells from each treatment group was isolated on day 35, treatments were washed away and cells stimulated with 1 µM prostratin (Sigma Aldrich) overnight. Approximately 16 hours later, supernatants and cell pellets were collected for PCR.

Construction of humanized BLT mice

BLT humanized mice were prepared as previously described (Denton et al., 2008; Denton et al., 2012; Denton et al., 2011; Melkus et al., 2006). Briefly, a 1–2 mm piece of human liver tissue was sandwiched between two pieces of autologous thymus tissue (Advanced Bioscience Resources) under the kidney capsule of sublethally irradiated (300 cGy) 6–8 week old NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG; The Jackson Laboratory) mice. Following implantation, mice were transplanted intravenously with hematopoietic CD34+ stem cells isolated from autologous human liver tissue. Human immune cell reconstitution was monitored in the peripheral blood of BLT mice by flow cytometry every 3–4 weeks. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions by the Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines for the housing and care of laboratory animals and in accordance with protocols reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. For the study that examined the impact of dCA on residual tissue viremia under ART, the mean weight of the mice used was 27.18 grams and they were 11 months old. For the study that examined the impact of dCA on viral rebound following therapy interruption, the mean weight of the mice used was 26.31 grams and the mice were between 7 and 9 months old. All mice used in these studies were female.

Production of viral stocks for infection of BLT mice

Stocks of HIV-1JRCSF were prepared as previously described (Wahl et al., 2012). Briefly, the proviral clone was transfected into human embryonic kidney (HEK)293T cells using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s protocols. Viral supernatant was collected 48 hours after transfection. Viral supernatant was titered by infecting TZM-bl cells at multiple dilutions. Virus containing medium was removed the next day, replaced with fresh DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum and the incubation continued for 24 hr. The cells were fixed and stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside and blue cells were counted directly to determine infectious particles per mL. Each titer of these viral stocks was performed in triplicate and at least two different titer determinations were performed for each batch of virus.

Statistical analysis

P-values for in vitro experiments were calculated using one-way ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis with post-hoc Dunn multiple comparison analysis or paired T-test with 95% confidence intervals using the Prism 7 for Macintosh (GraphPad software). All in vivo statistical analyses were also performed in Prism 7. A two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare levels of viral RNA in dCA treated mice with control vehicle treated mice.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Didehydro-Cortistatin A (dCA) reduces HIV transcription and reactivation from latency

dCA suppresses viral rebound after treatment interruption in HIV+ humanized BLT mice

dCA promotes epigenetic silencing of the HIV-1 promoter

“Block-and-lock” approach is a viable alternative for a functional HIV cure

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01AI097012, R01AI118432 (SV) and MH108179 and AI-111899 (JVG)). Research in this publication was also funded by CARE, a Martin Delaney Collaboratory, 1UM1AI126619. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We thank Michael Hudgens, Camden Bay, and Katie Mollan (UNC CFAR Statistical Core, P30 AI050410) for performing the statistical analysis presented in Table 1 and Bonnie Howell and Stephanie Barrett (Merck & Co.) for providing antiretroviral containing Chow. We also thank former and current members of the Garcia laboratory and the husbandry technicians at the UNC Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine for their assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the positions of the US Army or the Department of Defense.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Investigation, C.F.K., C.C.N., C.L., P.M.T., Methodology, C.F.K. C.C.N., C.L., H.T., G.M., J.V.G., L.T., M.F., J.B.H.; Conceptualization and Validation, C.F.K., C.C.N., J.V.G., S.V.; Writing and revisions, C.F.K., C.C.N., S.V., J.V.G.; Funding Acquisition, S.V.; Resources, J.V.G and S.V.; Supervision, J.V.G and S.V.

References

- Ananworanich J, Chomont N, Eller LA, Kroon E, Tovanabutra S, Bose M, Nau M, Fletcher JL, Tipsuk S, Vandergeeten C, et al. HIV DNA Set Point is Rapidly Established in Acute HIV Infection and Dramatically Reduced by Early ART. EBioMedicine. 2016;11:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananworanich J, Dube K, Chomont N. How does the timing of antiretroviral therapy initiation in acute infection affect HIV reservoirs? Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015;10:18–28. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DE, Bertagnolio S, Sutherland D, Gilks CF. The World Health Organization's global strategy for prevention and assessment of HIV drug resistance. Antivir Ther. 2008;13(Suppl 2):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui JK, Halvas EK, Fyne E, Sobolewski MD, Koontz D, Shao W, Luke B, Hong FF, Kearney MF, Mellors JW. Ex vivo activation of CD4+ T-cells from donors on suppressive ART can lead to sustained production of infectious HIV-1 from a subset of infected cells. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006230. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Ma J, Li J, Li D, Li G, Li F, Zhang Q, Yu H, Yasui F, Ye C, et al. Blocking type I interferon signaling enhances T cell recovery and reduces HIV-1 reservoirs. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:269–279. doi: 10.1172/JCI90745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun TW, Nickle DC, Justement JS, Large D, Semerjian A, Curlin ME, O'Shea MA, Hallahan CW, Daucher M, Ward DJ, et al. HIV-infected individuals receiving effective antiviral therapy for extended periods of time continually replenish their viral reservoir. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3250–3255. doi: 10.1172/JCI26197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun TW, Nickle DC, Justement JS, Meyers JH, Roby G, Hallahan CW, Kottilil S, Moir S, Mican JM, Mullins JI, et al. Persistence of HIV in gut-associated lymphoid tissue despite long-term antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:714–720. doi: 10.1086/527324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey RT, Jr, Bhat N, Yoder C, Chun TW, Metcalf JA, Dewar R, Natarajan V, Lempicki RA, Adelsberger JW, Miller KD, et al. HIV-1 and T cell dynamics after interruption of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with a history of sustained viral suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15109–15114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton PW, Estes JD, Sun Z, Othieno FA, Wei BL, Wege AK, Powell DA, Payne D, Haase AT, Garcia JV. Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis prevents vaginal transmission of HIV-1 in humanized BLT mice. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton PW, Long JM, Wietgrefe SW, Sykes C, Spagnuolo RA, Snyder OD, Perkey K, Archin NM, Choudhary SK, Yang K, et al. Targeted cytotoxic therapy kills persisting HIV infected cells during ART. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003872. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton PW, Olesen R, Choudhary SK, Archin NM, Wahl A, Swanson MD, Chateau M, Nochi T, Krisko JF, Spagnuolo RA, et al. Generation of HIV latency in humanized BLT mice. J Virol. 2012;86:630–634. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06120-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton PW, Othieno F, Martinez-Torres F, Zou W, Krisko JF, Fleming E, Zein S, Powell DA, Wahl A, Kwak YT, et al. One percent tenofovir applied topically to humanized BLT mice and used according to the CAPRISA 004 experimental design demonstrates partial protection from vaginal HIV infection, validating the BLT model for evaluation of new microbicide candidates. J Virol. 2011;85:7582–7593. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00537-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall C, Ernberg I, Gait MJ, Green SM, Heaphy S, Karn J, Lowe AD, Singh M, Skinner MA. HIV-1 tat protein stimulates transcription by binding to a U-rich bulge in the stem of the TAR RNA structure. EMBO J. 1990;9:4145–4153. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall C, Ernberg I, Gait MJ, Green SM, Heaphy S, Karn J, Lowe AD, Singh M, Skinner MA, Valerio R. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 tat protein binds transactivation-responsive region (TAR) RNA in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6925–6929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frange P, Faye A, Avettand-Fenoel V, Bellaton E, Descamps D, Angin M, David A, Caillat-Zucman S, Peytavin G, Dollfus C, et al. HIV-1 virological remission lasting more than 12 years after interruption of early antiretroviral therapy in a perinatally infected teenager enrolled in the French ANRS EPF-CO10 paediatric cohort: a case report. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e49–54. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama L, Abreu CM, Shirk EN, Price SL, Li M, Laird GM, Pate KA, Wietgrefe SW, O'Connor SL, Pianowski L, et al. Reactivation of simian immunodeficiency virus reservoirs in the brain of virally suppressed macaques. AIDS. 2017;31:5–14. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JV. In vivo platforms for analysis of HIV persistence and eradication. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:424–431. doi: 10.1172/JCI80562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthard HF, Havlir DV, Fiscus S, Zhang ZQ, Eron J, Mellors J, Gulick R, Frost SD, Brown AJ, Schleif W, et al. Residual human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Type 1 RNA and DNA in lymph nodes and HIV RNA in genital secretions and in cerebrospinal fluid after suppression of viremia for 2 years. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1318–1327. doi: 10.1086/319864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzakis AE, Touloumi G, Pantazis N, Anastassopoulou CG, Katsarou O, Karafoulidou A, Goedert JJ, Kostrikis LG. Cellular HIV-1 DNA load predicts HIV-RNA rebound and the outcome of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2004;18:2261–2267. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PW. Th17, gut, and HIV: therapeutic implications. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2010;5:189–193. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833647d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LE, Perelson AS. Transient viremia, plasma viral load, and reservoir replenishment in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:483–493. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180654836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao SY, Calman AF, Luciw PA, Peterlin BM. Anti-termination of transcription within the long terminal repeat of HIV-1 by tat gene product. Nature. 1987;330:489–493. doi: 10.1038/330489a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing CF, Spudich S, Valcour V, Cartwright P, Chalermchai T, Fletcher JL, Nichols C, Josey BJ, Slike B, Krebs SJ, et al. High Number of Activated CD8+ T Cells Targeting HIV Antigens are Present in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Acute HIV Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Redondo R, Fryer HR, Bedford T, Kim EY, Archer J, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Chung YS, Penugonda S, Chipman JG, Fletcher CV, et al. Persistent HIV-1 replication maintains the tissue reservoir during therapy. Nature. 2016;530:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature16933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkus MW, Estes JD, Padgett-Thomas A, Gatlin J, Denton PW, Othieno FA, Wege AK, Haase AT, Garcia JV. Humanized mice mount specific adaptive and innate immune responses to EBV and TSST-1. Nat Med. 2006;12:1316–1322. doi: 10.1038/nm1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau G, Clementz MA, Bakeman WN, Nagarsheth N, Cameron M, Shi J, Baran P, Fromentin R, Chomont N, Valente ST. An analog of the natural steroidal alkaloid cortistatin A potently suppresses Tat-dependent HIV transcription. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau G, Kessing CF, Fromentin R, Trautmann L, Chomont N, Valente ST. The Tat Inhibitor Didehydro-Cortistatin A Prevents HIV-1 Reactivation from Latency. MBio. 2015a;6:e00465. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00465-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau G, Mediouni S, Valente ST. Targeting HIV transcription: the quest for a functional cure. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015b;389:121–145. doi: 10.1007/82_2015_435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persaud D, Gay H, Ziemniak C, Chen YH, Piatak M, Jr, Chun TW, Strain M, Richman D, Luzuriaga K. Absence of detectable HIV-1 viremia after treatment cessation in an infant. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1828–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson T, McArthur J, Siliciano RF. Reservoirs for HIV-1: mechanisms for viral persistence in the presence of antiviral immune responses and antiretroviral therapy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:665–708. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafati H, Parra M, Hakre S, Moshkin Y, Verdin E, Mahmoudi T. Repressive LTR nucleosome positioning by the BAF complex is required for HIV latency. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez PW, Famiglietti M, Sowrirajan B, DePaula-Silva AB, Rodesch C, Barker E, Bosque A, Planelles V. Downmodulation of CCR7 by HIV-1 Vpu results in impaired migration and chemotactic signaling within CD4(+) T cells. Cell Rep. 2014;7:2019–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramratnam B, Ribeiro R, He T, Chung C, Simon V, Vanderhoeven J, Hurley A, Zhang L, Perelson AS, Ho DD, et al. Intensification of antiretroviral therapy accelerates the decay of the HIV-1 latent reservoir and decreases, but does not eliminate, ongoing virus replication. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:33–37. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razooky BS, Pai A, Aull K, Rouzine IM, Weinberger LS. A hardwired HIV latency program. Cell. 2015;160:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong L, Perelson AS. Modeling HIV persistence, the latent reservoir, and viral blips. J Theor Biol. 2009;260:308–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda CM, Velilla PA, Chougnet CA, Montoya CJ, Rugeles MT. HIV-induced T-cell activation/exhaustion in rectal mucosa is controlled only partially by antiretroviral treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez-Cirion A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Girault I, Lecuroux C, Potard V, Versmisse P, Melard A, Prazuck T, et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogaard OS, Graversen ME, Leth S, Olesen R, Brinkmann CR, Nissen SK, Kjaer AS, Schleimann MH, Denton PW, Hey-Cunningham WJ, et al. The Depsipeptide Romidepsin Reverses HIV-1 Latency In Vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005142. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toohey MG, Jones KA. In vitro formation of short RNA polymerase II transcripts that terminate within the HIV-1 and HIV-2 promoter-proximal downstream regions. Genes Dev. 1989;3:265–282. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann L, Labarriere N, Jotereau F, Karanikas V, Gervois N, Connerotte T, Coulie P, Bonneville M. Dominant TCR V alpha usage by virus and tumor-reactive T cells with wide affinity ranges for their specific antigens. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3181–3190. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3181::AID-IMMU3181>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann L, Rimbert M, Echasserieau K, Saulquin X, Neveu B, Dechanet J, Cerundolo V, Bonneville M. Selection of T Cell Clones Expressing High-Affinity Public TCRs within Human Cytomegalovirus-Specific CD8 T Cell Responses. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:6123–6132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Griend RJ, Van Krimpen BA, Bol SJ, Thompson A, Bolhuis RL. Rapid expansion of human cytotoxic T cell clones: growth promotion by a heat-labile serum component and by various types of feeder cells. J Immunol Methods. 1984;66:285–298. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl A, Swanson MD, Nochi T, Olesen R, Denton PW, Chateau M, Garcia JV. Human breast milk and antiretrovirals dramatically reduce oral HIV-1 transmission in BLT humanized mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002732. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AD, Weinberger LS. Stochastic fate selection in HIV-infected patients. Cell. 2013;155:497–499. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger LS, Dar RD, Simpson ML. Transient-mediated fate determination in a transcriptional circuit of HIV. Nat Genet. 2008;40:466–470. doi: 10.1038/ng.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen A, Rezek V, Youn C, Lam B, Chang N, Rick J, Carrillo M, Martin H, Kasparian S, Syed P, et al. Targeting type I interferon-mediated activation restores immune function in chronic HIV infection. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:260–268. doi: 10.1172/JCI89488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.