Abstract

Purpose

To examine the effect of a long-term structured physical activity intervention on accelerometer-derived metrics of activity pattern changes in mobility-impaired older adults.

Methods

Participants were randomized to either a physical activity (PA) or health education (HE) program. The PA intervention included a walking regimen with strength, flexibility, and balance training. The HE program featured health-related discussions and a brief upper body stretching routine. Participants (n = 1,341) wore a hip-worn accelerometer for ≥10 h/day for ≥3 days at baseline and again at 6, 12 and 24 months post-randomization. Total physical activity (TPA)—defined as movements registering 100+ counts/min—was segmented into the following intensities: low light (LLPA; 100–759 counts/min), high light (HLPA; 760–1,040 counts/min), low moderate (LMPA; 1,041–2,019 counts/min), and high moderate and greater (HMPA; 2,020+ counts/min) physical activity. Patterns of activity were characterized as bouts (defined as the consecutive minutes within an intensity).

Results

Across groups, TPA decreased an average of 74 minutes/week annually. The PA intervention attenuated this effect (PA= −68 vs. HE: −112 minutes/week, p=0.002). This attenuation shifted TPA composition by increasing time in LLPA (10+ bouts increased 6 min/week), HLPA (1+, 2+, 5+, and 10+ bouts increased 6, 3, 2, and 1 min/week, respectively), LMPA (1+, 2+, 5+, and 10+ bouts increased: 19, 17,16, and 8 min/week, respectively), and HMPA (1+, 2+, 5+, and 10+ bouts increased 23, 21, 17, and 14 min/week, respectively).

Conclusion

The PA intervention increased physical activity by shifting the composition of activity toward higher intensity activity in longer duration bouts. However, a long-term structured physical activity intervention did not completely eliminate overall declines in total daily activity experienced by mobility-impaired older adults.

Keywords: Light-intensity physical activity, accelerometer, elderly, physical activity intervention, activity bouts

INTRODUCTION

Adults aged 70+ years old are the most physically inactive age segment of the US population (31) and they are at high risk for physical disability and loss of independence (17). Large-scale physical activity intervention studies, such as the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders (LIFE) study (11), were developed to evaluate physical activity interventions to combat the negative effects of physical inactivity on mobility and independence. This was accomplished by facilitating older adults’ engagement in the Federally-recommended amount of 150 min/week (minutes per week) of structured moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) (3, 7, 23). Specifically, for those who have difficulty participating in long, continuous intervals or bouts of physical activity to reach 150 min/week, the guidelines recommend accumulating multiple 10+ minute bouts of activity spread throughout the week (23). Despite these recommendations, there is relatively little work to verify that physical activity interventions influence engagement in these types of activity bouts in vulnerable older adults who may have impediments to performing longer duration exercise.

Previous research has identified that physical activity interventions impact not only MVPA, but also reduce physical activity in lighter intensities among older adults, but not in younger adults. Several studies in younger populations demonstrated long-term (e.g., 5 months) physical activity interventions increased total daily physical activity suggesting that lighter intensity physical activity is preserved (6, 21, 27, 29). For example, Meijer and colleagues demonstrated that adults 28–41 years of age who trained 5 months for a 1/2 marathon competition increased total daily physical activity (21). The authors concluded that the physical activity training program did not affect light-intensity physical activity in this sample of younger adults, resulting in the observed increase of total amount of physical activity accumulated throughout the day. However, some evidence in older adults suggests that high intensity physical activity training has no impact on total daily physical activity, which may indicate that lighter intensity activities were replaced by higher intensity physical activity (14, 19, 20, 22). Older adults who undertook vigorous endurance training demonstrated no changes in total daily total energy expenditure (14). This suggests a compensation effect whereby lighter intensity activities reduced to accommodate increased engagement in higher intensity activities. However, the compensation effect remains largely unconfirmed in long-term, large-scale randomized trials and particularly among vulnerable older adults with mobility limitations. Furthermore, there has been little work to examine this compensation effect of physical activity according to frequency, duration, and intensity (34).

Measuring physical activity is challenging because it is difficult to precisely describe intensity patterns in free-living conditions. There are a multitude of measurement tools to assess physical activity including questionnaires, doubly-labeled water, and electronic sensors, all of which capture physical activity in different ways. However, some of these methods are limited in their ability to simultaneously capture all the complex components of daily physical activity such as frequency, duration, and intensity. Questionnaires are cost effective measurement tools that excel at qualitatively capturing types and contexts of activities and are easily deployed in large-scale research. However, validity (when compared to more objective methods) of these instruments is considered poor (16). Doubly labeled water is considered the gold standard method to indirectly measure free-living total caloric energy expenditure (30), but this method is costly for large scale research studies and unable to capture the type or intensity of specific activities performed during the monitored time period (35). Fortunately, innovations in engineering in the past couple decades have provided an objective method to assess movements continuously in free-living environments (13). Body worn accelerometers offer a non-invasive, reasonably cost-effective, and continuous measure of movement patterns throughout a waking day while also being well suited for evaluating behavioral studies such as physical activity interventions. Accelerometers have greatly expanded the measurement of physical activity by objectively capturing the composition of activity by intensity, duration, and frequency patterns, although they are not well-suited for capturing specific types or contexts of the physical activities being performed (25).

The primary aim of this analysis was to examine how a long term, moderate intensity physical activity intervention modified time spent at different intensities of physical activity as measured using an accelerometer. We hypothesized that the physical activity intervention would increase total daily time spent in levels within moderate intensity physical activity (stratified into low and ≥ high levels) by replacing time spent in light intensity physical activity (low and high) when compared to a general health education program. Second, this analysis aimed to determine whether the physical activity intervention modified patterns of engagement within different intensities. We hypothesized that the physical activity intervention would increase total daily time spent in 10+ minute bouts at all physical activity intensities when compared to a health education group. These hypotheses were tested in the LIFE study, which provides a unique opportunity to analyze accelerometer data collected at multiple time points over 2 years. The LIFE study enrolled a large sample of mobility-limited older adult population who were randomized into either a long-term, structured moderate intensity physical activity (PA) or a health education (HE) intervention (11).

METHODS

Trial Design and Participant Population

Details outlining the study design and methods (11) and primary results (24) can be found elsewhere. In short, the LIFE study was a Phase 3, multicenter, investigator-blinded, randomized clinical trial testing the capability of a physical activity intervention to reduce the risk of major mobility disability among mobility limited older adults. A total of 1,635 men and women were recruited who were 70–89 years of age and sedentary, defined as self-reporting < 20 minute/week getting regular physical activity within the last month. Also, eligible participants were tested for functional limitations operationally defined as scoring < 10 on the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), where 12 was the highest physical performance achievable. Moreover, eligibility required the ability to walk 400 meters within 15 minutes without sitting, leaning, or receiving any assistance. Participant exclusion criteria included not willing to be randomized, self-reported inability to walk across a room, plans to relocate in the near future, living in a nursing home, safety concerns such as chest pains or shortness of breath during the 400 meter walk, life expectancy < 12 months due to severe illness, and any clinical judgements concerning safety or study non-compliance. The LIFE study was registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov before trial enrollment (NCT01072500). Institutional review boards at all sites approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Interventions

Participants were randomized either to the PA or the HE intervention at baseline using a block algorithm (random block lengths) stratified by field center (8 centers throughout the United States) and sex. After randomization, participants received an individual face-to-face introductory session with a health educator who described the intervention, study expectations, and fielded any questions. Both programs promoted behavioral change based on social cognitive theory principles and strategies were developed around the Transtheoretical Model (26). The PA intervention comprised of an individually tailored plan to increase physical activity levels with a goal of achieving 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity physical activity by adopting multiple 10+ minute bouts throughout the week. This involved aerobic exercise through a walking regimen that also included lower extremity strength exercises, flexibility, and balance training. The PA intervention design consisted of two center-based sessions and three to four additional home physical activity sessions per week. The Borg’s scale for rating perceived exertion was utilized to determine whether participants attained moderate intensity physical activity (1). Participants were asked to reach an intensity of 13 (perceiving activity as “somewhat hard”) within a 6–20 range. Strength exercises consisted of 2 sets of 10 repetitions, where participants were asked to reach a 15 to 16 (perceiving activity as “hard”) on the Borg’s scale. The HE group participated in conversational workshops focused on older adult health and well-being, while intentionally avoiding topics related to physical activity. A few examples of the topics were the US healthcare system, how to travel safely, access to preventive services, and reliable health information sources. Additionally, participants in the HE group were led through a 5–10 minute seated, light intensity upper-extremity stretch and relaxation component during each session. Participants in the HE arm were expected to meet weekly during the first 26 weeks of the intervention and at least once monthly thereafter.

Accelerometer measurements

A hip-worn, triaxial accelerometer (Actigraph™ GT3X) was administered to each participant at baseline and then at 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-up visits. These devices detect accelerations within a magnitude range of 0.05 to 2.5 units of gravity, digitize the analog signals at a rate of 30 Hertz (Hz), and pre-process data through a band filter to eliminate non-human motion. Samples were summed over a 1-second interval, otherwise termed as epoch, and converted to activity counts. An activity count is a unit-less quantity of overall movement expressed as a rate (e.g., counts/minute). Participants were instructed to wear the accelerometers on their right hip at all times for seven consecutive days, except during sleep and water-related activities (e.g., swimming or showering). While triaxial accelerometer data were collected on the hip, only vertical axis data (most sensitive to ambulatory movements) were used in the current analysis (12, 18).

Physical activity variables

The accelerometer provides no information about whether a participant was wearing the device. Therefore, accelerometer data were first processed to classify valid wear time using Choi’s non-wear algorithm (5). This algorithm improves on previous methods at detecting low intensity activity, particularly in those who are expected to accumulate prolonged bouts of inactivity (31). In short, data were binned into 1-minute epochs and scanned for at least 90 minutes of consecutive zero counts. Any other non-zero count registered by the accelerometer was considered wear time. Non-zero counts were only allowed for up to two-minute intervals but within at least 30-minute upstream and downstream zero count windows. Outliers were identified as minutes where activity counts exceeded 10,000 counts/min, 3,500 counts over median of the 2nd highest activity counts/minute across all days, or 1,000 counts over the 2nd highest activity counts/minute of the same day. Minutes classified as outliers were re-labeled as non-wear time and not included in the analysis. In total, 34 of the 3,102 days (0.01%) from 18 participants were removed: one day from baseline, seven at 6 months, five at 12 months, and twenty-one from 24 months.

Physical activity patterns were characterized by intensity and bout lengths. Each valid wear minute was labeled as activity (of any intensity) if counts summed to 100+ activity counts over 1 minute. Accelerometer variables and accelerometer cut-points were calculated according to Table 1. The sum of all activity-labeled minutes was calculated as total activity (TPA) and categorized into low light physical activity (LLPA), high light physical activity (HLPA), low moderate physical activity (LMPA) and high moderate and greater physical activity (HMPA). These cut-points were chosen because they have been specifically evaluated among older adults (8, 12, 31). The percent contribution of intensity-specific activity to TPA was derived as follows: (minutes in intensity-specific activity) / (TPA) * 100. For example, if a participant spends an average of 1100 minutes per week in LLPA and 1300 minutes per week in TPA, the LLPA percentage of TPA is 1100/1300 × 100 or 85%.

Table 1.

Descriptions of accelerometer-derived metrics of physical activity composition

| Intensity | Bouts |

|---|---|

| Light physical activity (LLPA): | |

| • 100–759 counts/minut | • Time spent in 1+ minute bouts (minute/week; total activity time) |

| High light physical activity (HLPA): | |

| • 760–1,040 counts/minute | • Time spent in 2+ minute bouts (minute/week) |

| Low moderate physical activity (LMPA): | |

| • 1,041–2019 counts/minute | • Time spent in 5+ minute bouts (minute/week) |

| High moderate physical activity (HMPA): | |

| • 2,020+ counts/minute | • Time spent in 10+ minute bouts (minute/week) |

| Total physical activity (TPA): | |

| • 100+ counts/minute |

Bouts of activity time were calculated as the minimum amount of consecutive minutes (1, 2, 5, and 10 minutes) which the accelerometer register activity counts within cut-points specified in Table 1. Time spent in 1+ minutes of activity bouts represent the total volume of intensity-specific activity, where 2+, 5+, and 10+ minute bout lengths represent consecutively smaller segments of the total activity volume. We chose to examine overlapping categories of activity (e.g., 2+ minute bouts contain 5+ and 10+ minute bouts) because physical activity recommendations are typically disseminated with no upper limit. However, mutually exclusive categories can be calculated; for example, if 5+ minute bouts were subtracted from 2+ minute bouts, the subsequent segment would represent 2.0–4.9 minute bouts.

Other measurements

Participants were assessed at the clinical site at baseline and every six months thereafter by study staff masked to intervention group assignment. Information on age, sex, along with other sociodemographic factors, medical history, hospitalizations, medications, and quality of well-being were collected via self-report. Study staff objectively measured physical function via the 400-meter walk test (walking speed) and SPPB (physical performance).

Statistical analysis

Only participants who provided valid baseline accelerometry (10+ hours/day of accelerometer data for at least 3 days) were included in the analytic sample. Activity bout time distributions were assessed for normality within each intensity range prior to performing analyses. After verifying normality, mixed effects (random and fixed) linear regression models were constructed for each bout length and intensity level since distributions were found to be normal. Visit (time) was treated as a repeated factor, and the baseline activity-specific metric, age, visit, and wear time were included as fixed effects. Factors used to stratify randomization (sex and clinical site) were also included in both models as fixed effects. Also, the interaction between intervention arm and visit was tested for each model and included if found to be significant. Pairwise differences were presented for significant intervention arm by time interactions. Alpha level for all analyses was set to 0.05. Accelerometer data were processed using R (www.r-project.org) (5, 32) and statistical analyses were performed in STATA v13 (STATA Corp.).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Baseline participant characteristics according to intervention groups appear in Table 2. Randomized groups were similar across demographics, behavioral factors, and medical history. On average, participants were 79 years of age and predominately women (67%) and non-Hispanic white (76%). Mean wear time was 14 wear hours/day for an average of 8 days. Those with invalid accelerometer data (n=294) were similar in age (80 years old) and sex (70% women) compared to the sample with valid accelerometer data.

Table 2.

Baseline participant characteristics by randomized intervention group

| Physical activity (n = 669) |

Health education (n = 672) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean(SD) | 78.5 (5.3) | 78.9 (5.2) |

| Female, n(%) | 431 (64.4) | 461 (68.6) |

| Non-Hispanic White, n(%) | 497 (74.3) | 520 (77.4) |

| College or higher education, n(%) | 417 (62.3) | 430 (64.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean(SD) | 30.2 (5.8) | 30.5 (6.3) |

| Smoked 100+ cigarettes ever, n(%) | 339 (50.7) | 297 (44.2) |

| Modified Mini-Mental State Examination scorea, mean(SD) | 91.7 (5.4) | 91.7 (5.3) |

| Sought medical advice for depression in past 5 years, n(%) | 97 (14.5) | 85 (12.7) |

| Comorbidities > 2, n(%) | 172 (25.7) | 177 (26.3) |

| Short Physical Performance Battery score < 8b, n(%) | 286 (42.8) | 309 (46.0) |

| 400 meter walk < 0.8 m/sec, n(%) | 271 (40.5) | 296 (44.1) |

| Wear days, mean(SD) | 8.0 (3.3) | 7.9 (3.1) |

| Wear minute/day, mean(SD) | 839.1 (112.7) | 835.0 (109.4) |

| Minutes/day ≥ 760 counts, mean(SD) | 27.6 (22.8) | 27.9 (25.9) |

score range: 0–100 where higher scores indicate better performance

score range: 0–12 where higher scores indicate better performance; scoring < 8 indicates poor functioning

Activity intensity and bout lengths at baseline

Baseline daily activity patterns expressed in minutes per week by specific bout length are presented in Table 3. On average, participants spent 1,328 min/week in TPA, which made up 23% of total daily wear time per week. Of the total weekly TPA observed, 87% (1,134 min/week) was spent in LLPA, 6% (88 min/week) in HLPA, 6% (87 min/week) in LMPA, and 1% (19 min/week) in HMPA. Within LLPA, 73%, 24%, and 5% were spent in 2+, 5+, and 10+ minute bouts, respectively. Analyses showed that 22%, 1%, and 1% HPLA time was spent in 2+, 5+, and 10+ minute bouts, respectively. Of total LMPA time, 36%, 8%, and 2% were spent in 2+, 5+, and 10+ minute bouts, respectively. For HMPA, 30%, 9%, and 3% was spent in 2+, 5+, and 10+ minute bouts, respectively. No differences were noted between randomized groups.

Table 3.

Baseline weekly activity bouts by randomized intervention group

| Physical Activity (n=669) | Health Education (n=672) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (SD), minutes/week | n (%)a | mean (SD), minutes/week | n (%)a | |

|

|

||||

| Total physical activity minutes (100+ counts/minute) | ||||

| 1+ min bouts | 1,326.4 (483.9) | 669 (100) | 1,330.0 (495.1) | 672 (100) |

| 2+ min bouts | 911.4 (367.6) | 669 (100) | 916.5 (374.5) | 672 (100) |

| 5+ min bouts | 307.6 (185.0) | 668 (99.9) | 308.1 (183.7) | 672 (100) |

| 10+ min bouts | 65.0 (65.3) | 603 (90.1) | 68.0 (69.3) | 607 (90.3) |

| Low-light minutes (100–759 counts/minute) | ||||

| 1+ min bouts | 1,133.4 (380.6) | 669 (100) | 1,134.6 (381.4) | 672 (100) |

| 2+ min bouts | 840.7 (332.9) | 669 (100) | 841.9 (330.7) | 672 (100) |

| 5+ min bouts | 292.1 (181.0) | 668 (99.9) | 288.9 (172.9) | 672 (100) |

| 10+ min bouts | 59.4 (61.9) | 597 (89.2) | 59.7 (60.4) | 595 (88.5) |

| High-light minutes (760–1,040 counts/minute) | ||||

| 1+ min bouts | 88.5 (65.1) | 669 (100) | 88.1 (66.1) | 672 (100) |

| 2+ min bouts | 21.7 (21.4) | 634 (94.8) | 21.5 (21.6) | 625 (93.0) |

| 5+ min bouts | 1.1 (3.4) | 94 (14.1) | 1.1 (3.4) | 83 (12.4) |

| 10+ min bouts | 0.1 (1.1) | 3 (0.5) | 0.1 (1.2) | 7 (1.0) |

| Low-moderate minutes (1,041–2,019 counts/minute) | ||||

| 1+ min bouts | 85.8 (80.5) | 668 (99.9) | 88.4 (94.8) | 671 (99.9) |

| 2+ min bouts | 37.7 (47.3) | 622 (93.0) | 41.4 (62.7) | 621 (92.4) |

| 5+ min bouts | 8.7 (20.3) | 306 (45.7) | 11.7 (32.2) | 302 (44.9) |

| 10+ min bouts | 2.7 (11.4) | 72 (10.8) | 4.6 (20.5) | 82 (12.2) |

| High-moderate minutes (2,020+ counts/minute) | ||||

| 1+ min bouts | 18.6 (39.8) | 577 (86.3) | 19.1 (44.8) | 577 (85.9) |

| 2+ min bouts | 11.2 (32.6) | 331 (49.5) | 11.8 (35.1) | 320 (47.6) |

| 5+ min bouts | 5.7 (24.9) | 127 (19.0) | 6.5 (26.1) | 112 (16.7) |

| 10+ min bouts | 2.8 (18.3) | 45 (6.7) | 3.6 (18.2) | 54 (8.0) |

Frequency of those who spent any time in that activity level (minute/week > 0)

Most participants engaged in at least one minute of 1+, 2+, 5+ and 10+ minute bouts in LLPA (>85%) at baseline during the entire accelerometry collection period. This was also true for 1+ and 2+ minute bouts at HLPA and LMPA. However, in general, participants engaged in less activity with longer bout lengths and relatively higher intensity. Less than 15% of participants engaged in 10+ minute bouts at HLPA, LMPA, and HMPA.

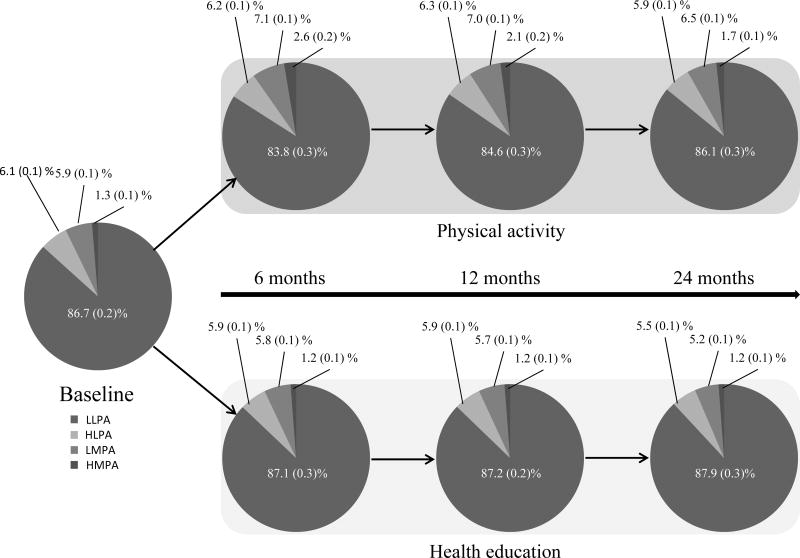

Intervention effects on the intensity composition of total physical activity time

Figure 1 illustrates adjusted annual percentages in intensity patterns, expressed as a percentage of TPA. The PA group decreased daily time spent in LLPA when compared to the HE group, with the highest impact observed at 6 months (−3%) but intervention effects diminished by 24 months (−2%; p interaction with time < 0.001). In comparison, the HE group increased time spent in LLPA by 1% (p=0.008) over 24 months. In contrast to LLPA, the PA group increased time spent in HLPA, LMPA, and HMPA when compared to the HE group. Intervention differences for HLPA and LMPA were <1% (p<0.001) and 1% (p<0.001), respectively. For HMPA, intervention differences were highest at 6 months (1%) but reduced by 24 months (<1%; p interaction with time < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Percent intensity changes, mean (SEM), within total daily physical activity by intervention.

Note: This figure expresses estimated annual percentages as a function of total physical activity. All models adjusted for baseline activity variable, age, sex, clinical site, and wear time.

LLPA – low light physical activity; HPLA – high light physical activity; LMPA – low moderate physical activity; HMPA high moderate and greater physical activity.

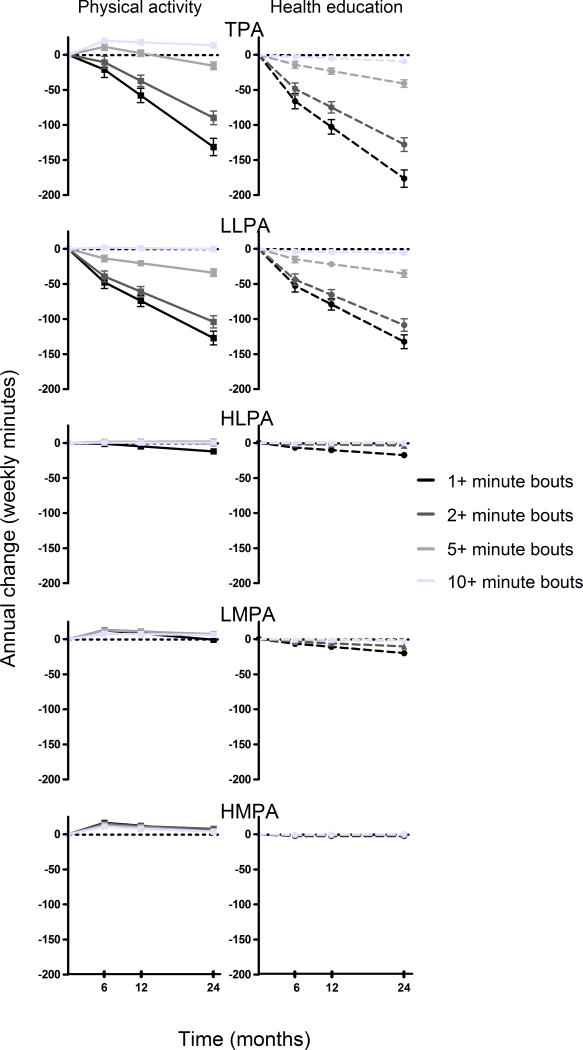

Intervention effects on time spent at intensities and bout lengths

Figure 2 depicts annual changes in TPA and levels within TPA (intensity level & bout length) by intervention group, expressed as a function of time (min/week). Both groups annually decreased TPA time in 1+ bouts (−74 min/week), 2+ bouts (−53 min/week), 5+ bouts (−18 min/week), and 10+ minute bouts (−4 min/week). However, the PA intervention attenuated TPA decreases across 1+, 2+, and 5+ minute bouts while increasing time in 10+ minute bouts when compared to the HE program (1+ bouts: +45 min/week; 2+ bouts: +38 min/week; 5+ bouts: +26 min/week; 10+ bouts: +23 min/week). After stratifying TPA by intensity, no intervention differences were detected for all bout lengths in LLPA except for 10+ minute bouts (+6 min/week). For HLPA, the PA intervention attenuated decreases in 1+ bouts (+6 min/week) and 2+ minute bouts (+3 min/week) while increased time in longer bouts (5+ minute bouts: + 2 min/week; 10+ minute bouts: +1 min/week). Intervention differences found in 1+, 2+, 5+, and 10+ minute HLPA bouts were maintained for 24 months (interaction with time p > 0.05 for all lengths). The PA intervention increased time in all LMPA bout lengths. Increases in 1+ bouts (+19 min/week), 2+ bouts (+17 min/week), and 10+ minute bouts (+8 min/week) were maintained for 24 months whereas 5+ minute bout increases were highest at 6 months (+14 min/week), maintained at 12 months (+12 min/week, p6vs12 diff=0.12), and reduced by 24 months (6 vs 24 months: +9 min/week, p12vs24 diff =0.02). For HMPA, the impact of the intervention was highest at 6 months where the PA intervention increased time in all bouts (1+ bouts: +20 min/week; 2+ bouts: +18 min/week; 5+ bouts: +14 min/week; 10+ minute bouts: +12 min/week). All increases in HMPA bouts reduced by 24 months (pinteraction with time <0.001 for all).

Figure 2.

Changes within activity intensity levels and bout patterns by intervention.

Note: This figure expresses estimated annual changes as a function of time (minutes/week). All models adjusted for baseline activity variable, age, sex, clinical site, and wear time. TPA – total physical activity; LLPA – low light physical activity; HPLA – high light physical activity; LMPA – low moderate physical activity; HMPA high moderate and greater physical activity.

DISCUSSION

The results provide an important understanding of the activity pattern changes that occur in response to a long-duration physical activity program in vulnerable older adults. First, the PA group continued to experience an overall decline in total daily activity, albeit less than the HE group. The PA intervention changed total daily activity by increasing HLPA, LMPA, and HMPA. These increases appeared to be at the expense of a decrease in LLPA. Second, the PA intervention increased engagement in long duration bouts of 10+ minutes of activity within LLPA, HLPA, LMPA, and HMPA when compared to the HE program. This finding was also supported by an increased time in short bouts (1+, 2+, and 5+ minute lengths) of HLPA, LMPA, and HMPA. It is important to note that group differences at lighter intensity bouts were not a sole result of increased physical activity in the PA group, but an attenuated decline when compared to the HE group.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first study to characterize activity composition among older adults aged 70–89 years old who were considered to be inactive (self-reported <20 min/week of structured physical activity) and had low physical function according to a standardized assessment battery (15). At baseline, LIFE participants accrued lower amounts of physical activity and performed less activity in longer bouts when compared to other studies on older adults. In 2008, Troiano and colleges reported from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data that older adults (70+ years) spent approximately 49 minutes/week of HMPA whereas our sample of mobility-limited older adults spent 19 minute/week (31). In a subsequent study by Evenson et al. using updated data, older adults accumulated approximately 364 minutes/week in HLPA, which is considerably higher than the 87 minutes/week in LIFE study participants (10). Additionally, in these same reports, older adults spent 21–49 minutes/week in 10+ min bouts of HMPA, whereas the LIFE sample spent 3 minutes/week (10, 31). More recently, Buman and colleges reported average time spent in LLPA (1,802 minutes/week), HLPA (132 minutes/week), and LMPA + HMPA (70 minutes/week) in 70+ year olds were substantially higher than participants in the LIFE study (2). These comparisons suggest that LIFE study participants were indeed less active across activity intensities and accumulated their activity in shorter bouts compared to the general population and other samples previously reported, indicating successful screening of mobility-limited older adults.

The PA intervention increased long term, moderate intensity physical activity while concurrent and proportional decreases time spent at light intensities were observed, confirming our first hypothesis. These results support previous findings that older populations do not simply add exercise into their daily lifestyle but compensate by reducing low intensity activities to accommodate higher intensity activity. This finding of a compensation effect is supported by previous studies implementing exercise training programs in older adults (14, 19, 20). In 1992, investigators observed no change in total physical activity, despite increases in vigorous intensity exercise measured through energy expenditure (14). Authors concluded that though older adults did not change total energy expenditure through a possible compensatory reduction in non-exercise activity, the high intensity training may have fatigued the participants afterwards. In 1999, a study using accelerometers assessed how a 3-month moderate intensity training program impacted daily physical activity in older adults aged 55–68 years old (20). Participants trained twice a week and accelerometry data were collected on training and non-training days. Results showed that training days showed a significant decrease of non-training physical activity when compared to physical activity accumulated on non-training days even with a lower intensity exercise program. Our results add to these findings by confirming the replacement effect occurring among older adults at high risk of mobility disability. Also unique to the literature is that we determined compositional changes in intensity levels of daily physical activity using accelerometers. At baseline, LIFE participants spent approximately 20% of total waking time in some form of physical activity. Of this 20%, LLPA was most predominant, reaching >80% of TPA. Over 24 months, the PA group experienced decreases in LLPA when compared to HE; the most observed at 6 months (−3%). At 6 months, the PA group concurrently increased time in HLPA, LMPA, and HMPA by 3% percent. Though intervention differences significantly reduced over time, the observed replacement effect was preserved over 24 months.

It appears that modifying the intensity composition of total daily activity can influence the maintenance of mobility and independence among vulnerable, older adults. In 2015, the LIFE study demonstrated that the PA intervention conferred mobility and health benefits to mobility-limited older adults (24). This may occur by replacing LLPA with higher activity intensities. Other studies have shown improvements in physical function and health markers, but not increases in total physical activity, associated with exercise training (14, 19, 20). In contrast, the HE group increased time in LLPA by replacing time in HLPA, LMPA, and HMPA and supports previous evidence of declines in physical activity after reaching the age of 60 years old (33). Daily intensity shifts within TPA were also experienced by the HE group but with higher activity intensities being replaced by LLPA. These results indicate that changes in the composition of physical activity intensities may be important for understanding transitions in disability and/or disease progression states (9), particularly among older adults with mobility impairments.

Participants in the PA intervention averaged 32–45 more minutes registering at or above 760 counts/minute per week than the HE group, which was similar to accelerometer data reported by Pahor and colleagues (24). By using Copeland’s cut-points (8), we found these intervention differences consisted of +6 minutes/week spent in HLPA, +19 minutes/week in LMPA and +20 minutes/week in HMPA at 6 months. Intervention differences maintained over 2 years except for HMPA increases, which diminished to +14 minutes/week at 12 months and +7 minutes/week at 24 months. For LLPA, group differences were observed only at 10+ minute bout types (+6 min/week). When combining all intensity levels, PA intervention accrued an average of 45 more min/week of TPA than the HE program. However, both groups experienced overall decreases in time spent in TPA over 24 months (−74 min/week of TPA per year), which was primarily driven by decreases in LLPA (−53 min/week of LLPA per year). Therefore, the PA intervention did not eliminate overall decreases but attenuated them. Additionally, we were able to examine intervention effects on volumes and bout patterns according to intensity level. In general, the PA intervention influenced bout patterns similar to their respective volumetric times. Intervention effects observed within HLPA and LMPA occurred similarly across longer bout times. However, intervention effects reduced over time for LMPA 5+ minute bouts and all HMPA bouts. The results support our second hypothesis that the PA intervention increased time spent in 10+ minute bouts at physical activity at all intensities when compared to the HE group. Additionally, the PA intervention attenuated but did not eliminate total daily physical activity declines despite increasing 10+ minute bouts of physical activity at higher intensity levels.

We were able to objectively evaluate a long-term physical activity intervention designed to increase amount of physical activity to Federally-recommended guideline levels. This capability was not restricted to the laboratory but expanded into free-living settings, revealing a novel and potentially useful way to assess unsupervised adherence. This is particularly important among older adults who have low adherence to unsupervised exercise programs while at home (4, 28). To do this, we combined commonly used accelerometer cut-points calibrated for adult populations (20+ years of age) to examine how the PA intervention influenced time spent at different activity intensities and bout lengths (8, 12, 31). This approach to examine intervention effects on daily activity accumulation patterns is unique to the accelerometer literature, particularly in vulnerable older adults at high risk of mobility disability.

Strengths of this study are objective collection of daily PA via accelerometers, repeated measures of accelerometry over 24 months, a large sample of older adults at high risk of mobility disability, and randomized controlled trial design. Limitations to acknowledge include lack of knowledge regarding posture— ability to detect standing versus sitting, sleep, and type of activity (e.g. structured exercise versus gardening). However, this population is less likely to stand for extended periods of time and the wear time classification algorithms reduces wear time misclassification among older adults (5). Further work is needed to understand the declines in total activity because it appears that increasing longer bouts of high intensity physical activity does not completely eliminate declines in total activity experienced by older adults highly vulnerable to mobility disability. This may involve strategies to incorporate a lifestyle component with a traditional, structured physical activity program to increase activity accumulation throughout the day.

Acknowledgments

The Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders Study is funded by a National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging Cooperative Agreement #U01 AG22376 and a supplement from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 3U01AG022376-05A2S, and sponsored in part by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH. AW is currently supported by T32AG000247 and previously supported for a majority of the work by T32AG020499 and a diversity supplement awarded by NIH/NIA P30AG028740 Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. TM is supported by R01AG042525 and R01HL121023.

Appendix

Administrative Coordinating Center, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Marco Pahor, MD – Principal Investigator of the LIFE Study, Jack M. Guralnik, MD, PhD – Co-Investigator of the LIFE Study (University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), Stephen D. Anton, PhD, Thomas W. Buford, PhD, Christiaan Leeuwenburgh, PhD, Susan G. Nayfield, MD, MSc, Todd M. Manini, PhD, Connie Caudle, Lauren Crump, MPH, Latonia Holmes, Jocelyn Lee, PhD, Ching-ju Lu, MPH. This research is partially supported by the University of Florida Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (1 P30 AG028740).

Data Management, Analysis and Quality Control Center, Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC

Michael E. Miller, Ph.D. – DMAQC Principal Investigator, Mark A. Espeland, Ph.D. – DMAQC Co- Investigator, Walter T. Ambrosius, PhD, William Applegate, MD, Daniel P. Beavers, PhD, MS, Robert P. Byington, PhD, MPH, FAHA, Delilah Cook, CCRP, Curt D. Furberg, MD, PhD, Lea N. Harvin, BS, Leora Henkin, MPH, Med, John Hepler, MA, Fang-Chi Hsu, PhD, Kathy Joyce, Laura Lovato, MS, Juan Pierce, AB, Wesley Roberson, BSBA, Julia Robertson, BS, Julia Rushing, BSPH, MStat, Scott Rushing, BS, Cynthia L. Stowe, MPM, Michael P. Walkup, MS, Don Hire, BS, W. Jack Rejeski, PhD, Jeffrey A. Katula, PhD, MA, Peter H. Brubaker, PhD, Shannon L. Mihalko, PhD, Janine M. Jennings, PhD.

National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

Evan C. Hadley, MD (National Institute on Aging), Sergei Romashkan, MD, PhD (National Institute on Aging), Kushang V. Patel, PhD (National Institute on Aging).

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD

Denise Bonds, MD, MPH.

Field Centers

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL

Mary M. McDermott, MD – Field Center Principal Investigator, Bonnie Spring, PhD – Field Center Co-Investigator, Joshua Hauser, MD – Field Center Co-Investigator, Diana Kerwin, MD – Field Center Co-Investigator, Kathryn Domanchuk, BS, Rex Graff, MS, Alvito Rego, MA.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA

Timothy S. Church, MD, PhD, MPH – Field Center Principal Investigator, Steven N. Blair, PED (University of South Carolina), Valerie H. Myers, PhD, Ron Monce, PA-C, Nathan E. Britt, NP, Melissa Nauta Harris, BS, Ami Parks McGucken, MPA, BS, Ruben Rodarte, MBA, MS, BS, Heidi K. Millet, MPA, BS, Catrine Tudor-Locke, PhD, FACSM, Ben P. Butitta, BS, Sheletta G. Donatto, MS, RD, LDN, CDE, Shannon H. Cocreham, BS.

Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

Abby C. King, Ph.D. – Field Center Principal Investigator, Cynthia M. Castro, PhD William L. Haskell, PhD, Randall S. Stafford, MD, PhD Leslie A. Pruitt, PhD, Veronica Yank, MD, Kathy Berra, MSN, NP-C, FAAN, Carol Bell, NP Rosita M. Thiessen Kate P. Youngman, MA Selene B. Virgen, BAS, Eric Maldonado, BA Kristina N. Tarin, MS, CSCS Heather Klaftenegger, BS Carolyn A. Prosak, RD Ines Campero, BA, Dulce M. Garcia, BS José Soto, BA Linda Chio, BA David Hoskins, MS.

Tufts University, Boston, MA

Roger A. Fielding, PhD – Field Center Principal Investigator, Miriam E. Nelson, PhD, Sara C. Folta, PhD, Edward M. Phillips, MD, Christine K. Liu, MD, Erica C. McDavitt, MS, Kieran F. Reid, PhD, MPH, Dylan R. Kirn, BS, Evan P. Pasha, BS, Won S. Kim, BS, Julie M. Krol, MS, Vince E. Beard, BS, Eleni X. Tsiroyannis, BS, Cynthia Hau, BS, MPH. Dr. Fielding’s contribution is partially supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement No. 58-1950-0-014. Any opinions, findings, conclusion, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Dept of Agriculture. This research is also supported by the Boston Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (1P30AG031679) and the Boston Rehabilitation Outcomes Center (1R24HD065688-01A1).

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Todd M. Manini, PhD – Field Center Principal Investigator, Marco Pahor, MD – Field Center Co- Investigator, Stephen D. Anton, PhD, Thomas W. Buford, PhD, Michael Marsiske, PhD, Susan G. Nayfield, MD, MSc, Bhanuprasad D. Sandesara, MD, Mieniecia L. Black, MS, William L. Burk, MS, Brian M. Hoover, BS, Jeffrey D. Knaggs, BS, William C. Marena, MT, CCRC, Irina Korytov, MD, Stephanie D. Curtis, BS, Megan S. Lorow, BS, Chaitalee S. Goswami, Melissa A. Lewis, Michelle Kamen BS, Jill N. Bitz, Brian K. Stanton, BS, Tamika T. Hicks, BS, Charles W. Gay, DC, Chonglun Xie, MD (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Holly L. Morris, MSN, RN, CCRC (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Floris F. Singletary, MS, CCC-SLP (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Jackie Causer, BSH, RN (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Susan Yonce, ARNP (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Katie A. Radcliff, M.A. (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Mallorey Picone Smith, B.S. (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Jennifer S. Scott, B.S. (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Melissa M. Rodriguez B.S. (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Margo S. Fitch, P.T. (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Mendy C. Dunn, BSN (Assessment) (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL), Jessica Q. Schllesinger, B.S. Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL). This research is partially supported by the University of Florida Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (1 P30 AG028740).

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

Anne B. Newman, MD, MPH – Field Center Principal Investigator , Stephanie A. Studenski, MD, MPH – Field Center Co-Investigator, Bret H. Goodpaster, PhD, Oscar Lopez, MD, Nancy W. Glynn, PhD, Neelesh K. Nadkarni, MD, PhD, Diane G. Ives, MPH, Mark A. Newman, PhD, George Grove, MS, Kathy Williams, RN, BSEd, MHSA, Janet T. Bonk, MPH, RN, Jennifer Rush, MPH, Piera Kost, BA (deceased), Pamela Vincent, CMA, Allison Gerger, BS, Jamie R. Romeo, BS, Lauren C. Monheim, BS. The Pittsburgh Field Center is partially supported by the Pittsburgh Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG024827).

Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC

Stephen B. Kritchevsky, Ph.D. – Field Center Principal Investigator, Anthony P. Marsh, PhD – Field Center Co-Principal Investigator, Tina E. Brinkley, PhD, Jamehl S. Demons, MD, Kaycee M. Sink, MD, MAS, Kimberly Kennedy, BA, CCRC, Rachel Shertzer-Skinner, MA, CCRC, Abbie Wrights, MS, Rose Fries, RN, CCRC, Deborah Barr, MA, RHEd, CHES. The Wake Forest University Field Center is, in part, supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (1 P30 AG21332).

Yale University, New Haven, CT

Thomas M. Gill, M.D. – Field Center Principal Investigator, Robert S. Axtell, PhD, FACSM – Field Center Co-Principal Investigator (Southern Connecticut State University, Exercise Science Department), Susan S. Kashaf, MD, M.P.H. (VA Connecticut Healthcare System), Nathalie de Rekeneire, MD, MS, Joanne M. McGloin, MDiv, MS, MBA, Raeleen Mautner, PhD, Sharon M. Huie-White, MPH, Luann Bianco, BA, Janice Zocher, Karen C. Wu, RN, Denise M. Shepard, RN, MBA, Barbara Fennelly, MA, RN, Rina Castro, LPN, Sean Halpin, MA, Matthew Brennan, MA, Theresa Barnett, MS, APRN, Lynne P. Iannone, MS, CCRP, Maria A. Zenoni, M.S., Julie A. Bugaj, MS, Christine Bailey, MA, Peter Charpentier, MPH, Geraldine Hawthorne-Jones, Bridget Mignosa, Lynn Lewis. Dr. Gill is the recipient of an Academic Leadership Award (K07AG3587) from the National Institute on Aging. The Yale Field Center is partially supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG021342).

Cognition Coordinating Center, Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC

Jeff Williamson, MD, MHS – Center Principal Investigator, Kaycee M Sink, MD, MAS – Center Co-Principal Investigator, Hugh C. Hendrie, MB, ChB, DSc (Indiana University), Stephen R. Rapp, PhD, Joe Verghese, MB, BS (Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University), Nancy Woolard, Mark Espeland, PhD, Janine Jennings, PhD, Valerie K. Wilson, MD

Electrocardiogram Reading Center, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Carl J. Pepine MD, MACC, Mario Ariet, PhD, Eileen Handberg, PhD, ARNP, Daniel Deluca, BS, James Hill, MD, MS, FACC, Anita Szady, MD

Spirometry Reading Center, Yale University, New Haven, CT

Geoffrey L. Chupp, MD, Gail M. Flynn, RCP, CRFT, Thomas M. Gill, MD, John L. Hankinson, PhD (Hankinson Consulting, Inc.), Carlos A. Vaz Fragoso, MD. Dr. Fragoso is the recipient of a Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Cost Effectiveness Analysis Center

Erik J. Groessl, PhD (University of California, San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System), Robert M. Kaplan, PhD (Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health).

Footnotes

The authors have no professional relationships with companies or manufacturers who will benefit from the results of the current study. The results do not constitute endorse by the American College of Sports Medicine. The authors declare that the results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no professional relationships with companies or manufacturers who will benefit from the results of the current study. The results do not constitute endorse by the American College of Sports Medicine. The authors declare that the results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

References

- 1.Borg G. Measuring perceived exertion and pain. Champaign, IL: Human kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buman MP, Hekler EB, Haskell WL, et al. Objective light-intensity physical activity associations with rated health in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(10):1155–65. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao D, Foy CG, Farmer D. Exercise adherence among older adults: challenges and strategies. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21(5):S212–S7. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi L, Liu Z, Matthews CE, Buchowski MS. Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(2):357–64. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ed61a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Church TS, Martin CK, Thompson AM, Earnest CP, Mikus CR, Blair SN. Changes in weight, waist circumference and compensatory responses with different doses of exercise among sedentary, overweight postmenopausal women. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee PAGA. Physical activity guidelines advisory committee report, 2008. Vol. 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. A1-H14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copeland JL, Esliger DW. Accelerometer assessment of physical activity in active, healthy older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2009;17(1):17–30. doi: 10.1123/japa.17.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiPietro L. Physical activity in aging changes in patterns and their relationship to health and function. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56(suppl 2):13–22. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evenson KR. Objective measurement of physical activity and sedentary behavior among US adults aged 60 years or older. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fielding RA, Rejeski WJ, Blair S, et al. The Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders Study: design and methods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(11):1226–37. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1998;30(5):777–81. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedson PS, Miller K. Objective monitoring of physical activity using motion sensors and heart rate. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(sup2):21–9. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2000.11082782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goran MI, Poehlman ET. Endurance training does not enhance total energy expenditure in healthy elderly persons. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism. 1992;263(5):E950–E7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.5.E950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helmerhorst HHJ, Brage S, Warren J, Besson H, Ekelund U. A systematic review of reliability and objective criterion-related validity of physical activity questionnaires. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirvensalo M, Rantanen T, Heikkinen E. Mobility Difficulties and Physical Activity as Predictors of Mortality and Loss of Independence in the Community-Living Older Population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5):493–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthew CE. Calibration of accelerometer output for adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S512–22. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185659.11982.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meijer E, Westerterp K, Verstappen F. Effect of exercise training on physical activity and substrate utilization in the elderly. Int J Sports Med. 2000;21(07):499–504. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meijer EP, Westerterp KR, Verstappen FT. Effect of exercise training on total daily physical activity in elderly humans. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1999;80(1):16–21. doi: 10.1007/s004210050552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meijer G, Janssen G, Westerterp K, Verhoeven F, Saris W, Ten Hoor F. The effect of a 5-month endurance-training programme on physical activity: evidence for a sex-difference in the metabolic response to exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1991;62(1):11–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00635626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morio B, Montaurier C, Pickering G, et al. Effects of 14 weeks of progressive endurance training on energy expenditure in elderly people. Br J Nutr. 1998;80(06):511–9. doi: 10.1017/s0007114598001603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116(9):1094. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2387–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plasqui G, Westerterp KR. Physical activity assessment with accelerometers: an evaluation against doubly labeled water. Obesity. 2007;15(10):2371–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rangan VV, Willis LH, Slentz CA, et al. Effects of an 8-month exercise training program on off-exercise physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(9):1744–51. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182148a7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robison J, Rogers MA. Adherence to exercise programmes. Sports Med. 1994;17(1):39–52. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199417010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenkilde M, Auerbach P, Reichkendler MH, Ploug T, Stallknecht BM, Sjödin A. Body fat loss and compensatory mechanisms in response to different doses of aerobic exercise—a randomized controlled trial in overweight sedentary males. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2012;303(6):R571–R9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00141.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoeller D, Van Santen E. Measurement of energy expenditure in humans by doubly labeled water method. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53(4):955–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Domelen DR. accelerometry-package. 2015 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/accelerometry/accelerometry.pdf.

- 33.Westerterp KR. Impacts of vigorous and non-vigorous activity on daily energy expenditure. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62(03):645–50. doi: 10.1079/PNS2003279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westerterp KR. Pattern and intensity of physical activity. Nature. 2001;410(6828):539. doi: 10.1038/35069142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westerterp KR, Plasqui G. Physical activity and human energy expenditure. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7(6):607–13. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200411000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]