Abstract

BACKGROUND

Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are urgently needed to treat the growing number of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or at immanent risk for AD. A definition of DMT is required to facilitate the process of DMT drug development.

PROCESS

This is a review of the state of the science with regard to definition and development of DMTs.

RESULTS

A DMT is as an intervention that produces an enduring change in the clinical progression of AD by interfering in the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of the disease process that lead to cell death. Demonstration of DMT efficacy is garnered through clinical trial designs and biomarkers. Evidence of disease modification in the drug development process is based on trial designs such as staggered start and delayed withdrawal showing an enduring effect on disease course or on combined clinical outcomes and correlated biomarker evidence of an effect on the underlying pathophysiological processes of the disease. Analytic approaches such as showing change in slope of cognitive decline, increasing drug-placebo difference over time, and delay of disease milestones are not conclusive by themselves but support the presence of a disease modifying effect. Neuroprotection is a related concept whose demonstration depends on substantiating disease modification. No single type of evidence in itself is sufficient to prove disease modification – consistency, robustness, and variety of sources of data will all contribute to convincing stakeholders that an agent is a DMT.

CONCLUSION

DMT is defined by its enduring effect on processes leading to cell death. A variety of types of data can be used to support the hypothesis that disease modification has occurred.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, biomarker, amyloid, disease modifying therapy, staggered start

Introduction

Disease-modifying therapy (DMT) is a major goal of research in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) therapeutics. People with or at risk for AD, caregivers and family members, academic scientists, advocacy groups, biopharma industry scientists, the National Institutes of Health and other funders, and regulatory agencies are all stakeholders in the search for drugs or other interventions that can prevent or defer the onset or slow the decline of AD. Putative DMTs build on an increasingly sophisticated neurobiological understanding of AD and intervene in steps thought to be critical to the pathophysiological process leading to cell death and expressing itself clinically as disease progression. The search for DMTs has taken on increased urgency as the world faces the tsunami of AD occurring with the aging of the global population (1). Simultaneously, the discovery of the long preclinical phase of AD has revealed the great number of people who have AD-type changes in the brain and are at risk for the emergence of clinical manifestations (2, 3). DMTs are warranted in this population to prevent or defer disease emergence.

Despite the obvious need for treatments that will change the course of AD, the large number of programs directed at finding such agents, and the size of the population involved or at risk, there has been relatively little discussion or consensus building about the definition of DMT or the data needed to meet the definition. Much of the information is in regulatory documents (4, 5). A definition is necessary to identifying appropriate clinical outcomes, develop biomarkers, and design trials that will demonstrate disease modification and meet agreed upon criteria.

In this paper, we address key issues of the concept of disease modification and DMTs and offer a framework for collecting data in clinical trials supportive of disease modification by the candidate therapy.

Defining Disease-Modifying Therapy

The three key elements of DMT are disease, modifying, and therapy (4–6).

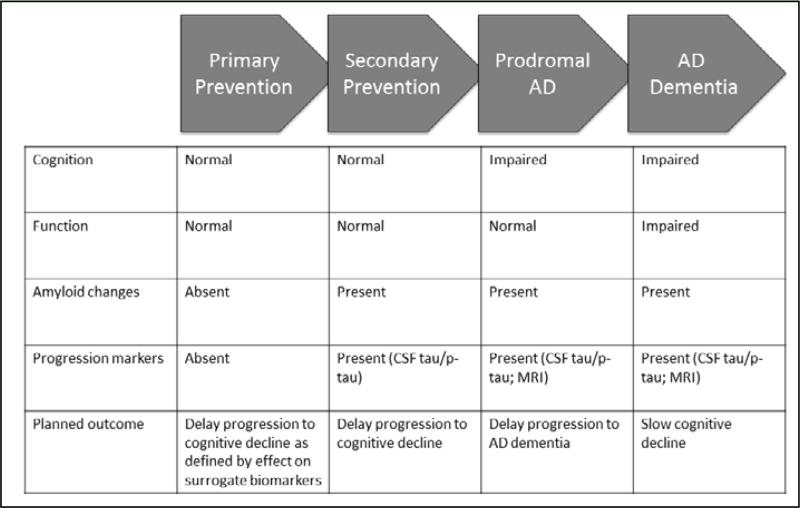

”Disease” includes the preclinical phase of AD when there is evidence of fibrillar amyloid deposition in the brain on amyloid imaging or abnormally low levels of the 42 amino acid amyloid beta protein (AB42) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in a subject who has normal cognition and function; prodromal AD identified by the presence of the same Aβ abnormalities in individuals who have some degree of cognitive impairment but do not meet criteria for dementia; and individuals with biological and clinical evidence of AD dementia. (7, 8). Figure 1 shows the populations of AD in which DMT development is being pursued. There is a lack of consensus on whether the preclinical phase as described here is properly considered a disease since there are no symptoms, but treatments provided in this stage are aimed at preventing the symptomatic phases of AD and can be considered as DMTs. Preclinical applications of DMTs can include both primary prevention, beginning with individuals who have no evidence of AD pathology, or secondary prevention in individuals who are cognitively normal but have positive amyloid imaging or other biomarker evidence of the presence of AD pathology.

Figure 1.

Stages of Alzheimer’s disease applicable to development of disease modifying therapies

“Modifying” is the key word in the definition of DMT and is considered in more detail throughout this paper. The concept of modification is based on extrapolation from basic science observations that have identified processes in cellular studies, animal models, or human pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that result in AD-like changes and that can be altered by treatment (9, 10). For human application, “modification” refers to a change in the underlying disease process that produces an enduring effect on the clinical course of AD. Pathological processes of AD possibly contributing to cell death and representing targets for DMT’s include amyloid toxicity, tau-related cytopathy, disruption of membrane integrity, inflammation, oxidation, apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, synaptic loss, cell loss, heavy metal-related facilitation of neuronal injury, demyelination, and possibly other processes yet to be identified.

“Therapy” refers to a structured intervention that might include a pharmacologic agent, device, or nonpharmacologic activity such as exercise (11).

Disease modification is an inferential concept based on trial-derived data since direct observation of the changes in the brain is not feasible. The data necessary to provide evidence of an enduring clinical effect and disease modification are generated in clinical trials using clinical outcomes and biomarkers. Trial design and analytic strategies are used to optimize the ability to demonstrate drug-placebo differences supportive of disease-modification.

The concept of DMT stands in contrast to the idea of “symptomatic” therapy defined as interventions that improve cognition, defer cognitive or functional decline, or ameliorate symptoms such as agitation, depression or delusions without altering the underlying disease processes that comprise AD pathogenesis and without producing enduring changes that persist when the treatment is withdrawn. Symptomatic therapies may be based on disease-related concepts such as a cholinergic deficiency but are not intended to interrupt processes leading to cell death. Symptomatic treatments such as cholinesterase inhibitors have been shown to delay disease progression as measured by cognitive and functional measures (12); delay of symptoms does not constitute proof of disease-modification.

Based on the critical elements, a DMT can be defined as an intervention that produces an enduring change in the clinical progression of AD by interfering in the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of the disease process leading to cell death. Data supporting an intervention as a DMT would meet one of two criteria: 1) the intervention produces a significant drug-placebo difference on accepted clinical outcome(s) and has a consistent effect on one or more validated biomarkers considered fundamental to AD pathophysiology, or 2) the intervention produces a positive outcome on a staggered start or delayed withdrawal clinical trial design consistent with an enduring change in clinical course. The interpretation of biomarker results will depend on the repertoire of biomarkers tested, their internal consistency, relationship to the proposed mechanism of action, dose-response observations, and effect on proposed “downstream” events. This DMT definition is not the same as specifying the requirements for approval of a DMT by a regulatory body; regulatory agencies address such issues as the necessary number of trials, quality of trials and trial data, and clinical meaningfulness of the observations.

Disease modification has synergies with the concept of “neuroprotetction.” The latter refers to interventions that favorably influence the disease process or underlying pathogenesis to produce enduring benefits for patients (13, 14). The clinical benefit is achieved by forestalling onset of illness or clinical decline. Effective neuroprotection results in disease modification and efficacious neuroprotective therapies are disease-modifying. Neuroprotection may be primary if the mechanism of action is directly on the neuron (e.g., mitochondrial agents) or secondary if the protection is derived from an action on an intermediary that compromises neuronal function. Neuroprotection achieved with multiple sclerosis therapies, for example, is proposed as secondary neuroprotection from effects on inflammation.

Neuroprotection and disease modification are concepts that apply broadly across neurodegenerative diseases (15, 16).

Regulatory Views of Disease Modification

In its guidance on “Alzheimer’s Disease: Developing Drugs for Treatment of Early Stage Disease” (4) the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) described two approaches to demonstrating disease modification: 1) clinical benefit supported by a meaningful effect on a biomarker, or 2) clinical trial design suited to demonstrating a lasting effect on the disease course. They stated that a divergence of slope of decline might be produced by a pharmacologically reversible effect and is not by itself evidence of disease modification. They noted that a biomarker effect cited in support of disease modification must reflect a pathophysiological entity that is fundamental to the underlying disease process. They observed that there is currently insufficient evidence on which to base a hierarchical structuring of biomarkers and encouraged trial sponsors to analyze the results of biomarkers independently. The FDA guidance observed that randomized start and randomized withdrawal trial designs with clinical outcomes can provide evidence of enduring effects consistent with disease modification. They stated that for ethical reasons, the randomized start design would be most appropriate for trials of patients with AD.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) discussion of AD therapy states that a medicinal product can be considered to be disease modifying when it delays the underlying pathological or pathophysiological disease processes (5). It states that this can be demonstrated by results that show slowing of the rate of decline of clinical signs or symptoms when these results are linked to a significant effect on adequately validated biomarkers that reflect key pathophysiological aspects of the underlying disease process. EMA noted that change in rate of decline as shown by slope analysis and increasing drug-placebo difference are analyses that can support a disease-modifying effect. Delayed start or withdrawal designs were described as options to enhance the data derived from a trial intended to show disease modification. EMA suggested that if biomarker results are unclear, an alternative treatment labeling such as “delay or slowing in rate of decline” may be acceptable if effects on cognition and function are demonstrated.

Trial Design and Data Analysis to Support Disease Modification

Delayed start and randomized withdrawal are clinical trial designs that provide evidence of disease modification (17). In the delayed start design, one subject group is started on treatment later than another and the failure to “catch up” with the first indicates that there has been an enduring effect on the disease and the effect of the drug is more than symptomatic. In the randomized withdrawal design, a treated subject group is withdrawn from therapy and if they do not assume the same level of function as an untreated group, then the disease has been modified (18). There are substantial uncertainties with these proposed designs such as the appropriate duration of the period between the start of treatment of groups 1 and 2 in the delayed start and the required duration of the period of observation of the withdrawn group in the randomized withdrawal design. No study has successfully utilized these designs to establish disease-modification in a neurodegenerative disorder.

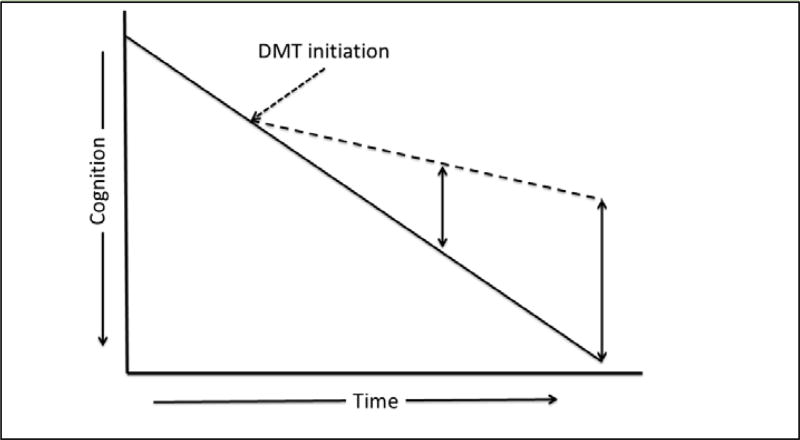

In addition to the trial design, strategies for data analysis can contribute to supporting the presence of disease-modification in trials of DMTs. Four major analytic approaches have been used in clinical trials: 1) drug-placebo difference at trial end; 2) delay to milestone (e.g, progression to Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] (19) to 1 from 0.5 or to 2 from 1); 3) increasing drug placebo difference over time; and 4) change in slope of decline. Drug-placebo difference at trial end and delay to milestone are not unique to disease modification and can be produced by symptomatic agents (12). Change in slope from more acute to less acute with successful intervention and increasing drug-placebo difference over time are supportive of disease-modification (Figure 2) (18) Neither of these are sufficiently informative by themselves to establish disease modification. These observations are expected in DMT trials and can add support to the case for disease modification. EMA has suggested that these analyses might be supportive of a “slowing in rate of decline” (5); that could serve as an alternative label for a candidate agent that failed to meet all criteria for a DMT.

Figure 2.

Analytic observations consistent with disease modification

Clinical Outcomes to Demonstrate Disease Modification

A successful DMT must produce meaningful clinical benefit. New outcome instruments are required to show the clinical dimension of disease-modification in recently identified trial populations such as those with normal cognition in prevention trials and those with mild cognitive changes in prodromal AD trials. In primary prevention trials, DMTs would be expected to delay the development of biomarker evidence of AD (e.g, delay of amyloid accumulation as shown by amyloid imaging) and thereby to delay the onset of cognitive decline. No biomarker has been shown to be a surrogate of clinical decline in AD and trials will be forced to use biomarkers that are “reasonably likely” to predict clinical benefit. Such approaches have been used in development of drugs for other disease states such as human immunodeficiency virus infections (20). Confirmation of the disease modifying effect on cognition would require observation of the treated patients for long periods of time. Primary prevention might be instituted at age 50 or 55, delayed amyloid deposition might be evident after 4–5 years of treatment, but delay of cognitive decline would require observation until age 65 or 70 – 20 years after the initiation of therapy. These timeframes will require use of putative fit-for-purpose biomarkers that may eventually be shown to be predictive of cognitive function. Biomarker effects by themselves if considered reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit might be sufficient for accelerated approval requiring demonstration of cognitive effects with longer term observation after approval.

Secondary prevention trials enroll individuals who are cognitively normal but who have biomarker evidence (e.g., positive amyloid imaging; CSF signature of AD) of being at high risk for the development of cognitive decline. The combination of delay of onset of cognitive decline compared to placebo and biomarker changes supportive of an impact on the fundamental pathophysiology of AD would be key to establishing an agent as a DMT.

Prodromal AD is the predementia stage of AD in which patients have cognitive impairment without functional deficits, do not meet criteria for dementia, and have a biomarker indicative of the presence of AD pathology (positive amyloid imaging; CSF signature of AD) (8). The FDA has issued a guidance concerning trials in this population and has suggested that composite measures such as the Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes (CDR-sb) (19) could function as a single trial outcome although benefit on both the cognitive and functional portions of the measure is expected (4). Several alternative composites have been proposed for this role including the integrated AD Rating Scale (iADRS) (21) and the AD Composite Scale (ADCOMS) (22). Support for disease modification could be obtained by showing a drug-placebo difference at trial end on the composite score and on a suite of biomarkers, or the composite could be used as the outcome in a staggered start or randomized withdrawal trial design. Expectations for functional outcomes in this population are ambiguous since the prodromal population by definition lacks functional impairment.

DMTs would also be appropriate for treatment of AD dementia especially in early stages when cognitive and functional deficits remain compatible with acceptable quality of life. In some studies, prodromal and mild AD dementia are included in the same trial population in recognition of the arbitrary nature of dividing the seamless spectrum of progressive cognitive decline that characterizes AD. Clinical outcomes in these populations would require showing a drug-placebo benefit on cognitive and functional or global outcomes. The clinical outcomes would require support of concurrent biomarker differences to establish an agent as a DMT. Alternatively, the outcomes could be used in staggered start or randomized withdrawal designs.

Establishment of disease modification is dependent on the measurement characteristics of the tools (clinical and biomarker) used as well as the quality of execution of the clinical trial.

Biomarkers to Demonstrate Disease Modification

There is currently a limited repertoire of biomarkers of AD; none have achieved the status of a surrogate marker that is known to reliably predict clinical outcomes and can be substituted for clinical measures in trials. Two biomarkers have been qualified by the EMA and can be used in clinical trials without re-qualification for individual trials. These are low CSF Aβ42 and hippocampal atrophy as measured on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (23, 24). No AD biomarkers have been qualified by the FDA, and biomarkers used as outcome measures in trials of DMTs must be established as fit-for-purpose for each trial (25).

Biomarkers can be divided into diagnostic biomarkers that identify the presence of AD type pathology and pathophysiological biomarkers that reflect disease progression (8). Recognized diagnostic biomarkers include amyloid imaging documenting abnormal amyloid levels and the CSF signature of AD comprised of low Aβ42 and high tau or phospho-tau (p-tau). Biomarkers reflecting disease progression include measures of brain atrophy using MRI, assessment of cerebral metabolism using fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), CSF levels of tau and p-tau, and tau PET.

Effects on diagnostic biomarkers do not by themselves support disease-modification. Bapineuzumab and AN-1792 are examples of immunotherapies that reduced plaque burden in clinical trials and did not affect the course of decline in AD (26, 27). Removal of plaque amyloid documents an effect of treatment on fibrillar amyloid but not necessarily an effect on processes leading to cell death.

Effects on biomarkers of disease progression could be regarded as evidence in support of disease-modification. Reduction of whole brain or hippocampal atrophy compared to atrophy in a placebo group would be regarded as supportive of disease-modification if seen in conjunction with clinical benefit. Several trials have shown greater atrophy in groups treated with putative DMTs compared to placebo controls and a comprehensive understanding of the influences on this measure has yet to be achieved (28, 29). Less elevation of CSF tau or p-tau in the treatment group compared to the placebo or reduced tau accumulation as seen on tau imaging would be regarded as evidence of disease modification (30). Less marked reduction of cerebral metabolism on FDG PET would support a disease-modifying effect; this evidence should be viewed with caution as changes on FDG PET can be produced by symptomatic agents such as cholinesterase inhibitors (31).

FDA has suggested that multiple biomarkers should be collected in clinical trials. Assessing amyloid imaging and CSF Aβ42 could provide internally consistent evidence of an effect on amyloid physiology. Similarly, collecting simultaneous measures of tau abnormalities – tau imaging, CSF tau/p-tau – might convincingly support a tau-related drug effect (32).

Pathophysiological events in AD are hypothesized to be linked, with amyloid changes being “upstream” and tau alterations, inflammation and cell loss being “downstream” (33). Measures of several biomarkers that indicate effects on different elements of the pathophysiology would be supportive of a disease-modifying effect independent of the veracity of our current disease models. Thus, measures of Aβ42, CSF tau/p-tau, and whole brain atrophy on MRI could provide a more comprehensive view of the effects of a DMT and a more compelling suite of observations. The interpretation of biomarker results will depend on the repertoire of biomarkers tested, their internal consistency, relationship to the proposed mechanism of treatment action, dose-response observations, and effect on proposed “downstream” events.

Linking the observed biomarker effect to the observed clinical effect is important to support the effects of a DMT. Biomarker and clinical effects could be achieved through different mechanisms of drug action (20). A relationship between the clinical and biological effects is indicated by correlations between the magnitude of change on clinical and biomarker measures. A dose-response relationship between administered dose or serum level and biomarker effect would provide further evidence of a causative relationship.

Classifying Evidence in Support of Disease Modification

Data supporting disease modification are inferential based on biomarkers of biological effects; no direct measures of disease modification are available. No single piece of evidence will prove that an agent has produced disease modification. Synthesis of clinical outcomes, biomarker outcomes, trial designs, and analytic strategies supported by non-clinical studies of mechanism of drug action will be required to provide compelling support for disease modification (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data supporting disease-modification by a putative DMT

| Trial design |

| • Staggered start |

| • Randomized withdrawal |

| • Drug-placebo difference at trial completion on accepted clinical outcomes and validated biomarkers |

| • Delay to clinical milestones with supporting biomarkers |

| Supportive analyses of the trial data |

| • Change in slope of decline over multiple observation points |

| • Increasing drug-placebo difference over time |

| • Biomarker changes correlated with clinical changes |

| • Dose response relationship of clinical outcomes with the intervention |

| • Delay to milestone (e.g., % of subjects with prodromal AD reaching CDR 1 at specified times) |

| • In a modified delayed start design, observe if patients switched from placebo to active therapy when entering the open label extension phase of the study “catch up” with those on active treatment throughout the study |

| Biomarker measures |

| • Single biomarker outcomes reflecting an effect on underlying pathophysiology contributing to clinical progression |

| • Multiple biomarker outcomes measuring one aspect of the disease (e.g, CSF Aβ and amyloid imaging) |

| • Multiple biomarker outcomes assessing downstream or independent effects of an intervention (e.g, CSF tau/p-tau or MRI following anti-amyloid treatment) |

| • Dose-response relationship of biomarker changes with the intervention |

| Non-clinical observations |

| • Effect on mechanisms central to the proposed pathophysiology of AD |

The combination of clinical and biological observations allows the construction of levels of evidence in support of disease modification collected in trials. Staggered start and randomized withdrawal evidence is more compelling than parallel group designs, and effects on multiple independent biomarkers are more compelling that effects on single biomarkers or related biomarkers. Table 2 presents an approach to classification of levels of evidence in support of a DMT for mild-moderate AD trial outcomes; similar approaches could be applied to prevention trials and trials involving prodromal AD.

Table 2.

Approach to levels of clinical and biomarker evidence in support of disease modification

| Population | Level of Evidence | Clinical Design | Clinical Outcome | Biomarker Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild-Moderate AD | A1 | Delayed start or delayed withdrawal | Significant effect on cognitive and functional or global measures | Significant effects on several independent biomarkers |

| A2 | Parallel group | Significant effect on cognitive and functional or global measures | Significant effects on several related biomarkers | |

| B1 | Delayed start or delayed withdrawal | Significant effect on cognitive and functional measures | Significant effects on one biomarker or biomarkers limited to one aspect of AD | |

| B2 | Parallel group | Significant effect on cognitive and functional measures | Significant effects on one biomarker or biomarkers limited to one aspect of AD | |

| C1 | Parallel group | Trend on cognitive and functional measures | Significant effects on several independent biomarkers | |

| C2 | Parallel group | Trend on cognitive and functional measures | Significant effects on one biomarker or biomarkers limited to one aspect of AD |

Summary

AD is increasingly well understood from a neurobiological perspective. New targets are being identified as the processes involved in the disease are better defined. More candidate molecules are being identified and entered into the AD therapeutic pipeline (34). Many of these agents are intended to be DMTs that will prevent, delay or slow the progression of AD. Success in developing DMTs grows more urgent as the population of those with or at risk for AD increases. A definition of DMT is key to advancing a therapeutic agenda. The recommendations offered here for defining DMTs and providing data to support identification of DMTs are intended to assist in the critical process of developing DMTs.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding: JC acknowledges the funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant: P20GM109025) and support from Keep Memory Alive. NF acknowledges the support of the Leonard Wolfson Experimental Neurology Centre, the NIHR Queen Square Dementia Biomedical Research Unit, and UCL/UCLH Biomedical Research Centre. The Dementia Research Centre is supported by Alzheimer’s Research UK, Brain Research Trust, and The Wolfson Foundation. The Dementia Research Centre is an Alzheimer’s Research Centre Co-ordinating Centre. This work was supported by The Dunhill Medical Trust [grant number R337/0214]; Alzheimer’s Society (AS-PG-14-022); ESRC/NIHR (ES/L001810).

Disclosures: JC has provided consultation to Abbvie, Acadia, Actinogen, Alzheon, Anavex, Avanir, Axovant, Boehinger-Ingelheim, Bracket, Eisai, Forum, GE Healthcare, Genentech, Intracellular Interventions, Lilly, Lundbeck, Medavante, Merck, Neurocog, Novartis, Orion, Otsuka, Pfizer, Piramal, QR, Roche, Suven, Sunovion, Takeda and Toyama pharmaceutical and assessment companies. NF consults for Eli Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline GSK. NF consults for Eli Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline GSK.

Footnotes

Ethical standards: This review paper did not involve new subject testing and did not compromise ethical standards.

References

- 1.Sosa-Ortiz AL, Acosta-Castillo I, Prince MJ. Epidemiology of dementias and Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Med Res. 2012;43:600–608. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pietrzak RH, Lim YY, Ames D, et al. Trajectories of memory decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Flagship Study of ageing. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Alzheimer’s Disease: Developing drugs for the treatment of early stage disease. Washington, D.C.: 2013. [updated 2/2013]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm338287.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Medicine Agency; Committee For Medicinal Products For Human Use. Draft guideline on the clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2016 EMA/CHMP/539931/2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings JL. Defining and labeling disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi SH, Kim YH, Hebisch M, et al. A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2014;515:274–278. doi: 10.1038/nature13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurtado DE, Molina-Porcel L, Iba M, et al. A{beta} accelerates the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology and augments tau amyloidosis in an Alzheimer mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1977–1988. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duara R, Barker W, Loewenstein D, Bain L. The basis for disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer’s disease: the Sixth Annual Mild Cognitive Impairment Symposium. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohs RC, Doody RS, Morris JC, et al. A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients. Neurology. 2001;57:481–488. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravina BM, Fagan SC, Hart RG, et al. Neuroprotective agents for clinical trials in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic assessment. Neurology. 2003;60:1234–1240. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058760.13152.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiendl H, Elger C, Forstl H, et al. Gaps between aims and achievements in therapeutic modification of neuronal damage («neuroprotection») Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12:449–454. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitcup SM. Clinical trials in neuroprotection. Prog Brain Res. 2008;173:323–335. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)01123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunkel P, Chai CL, Sperlagh B, Huleatt PB, Matyus P. Clinical utility of neuroprotective agents in neurodegenerative diseases: current status of drug development for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1267–1308. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.703178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodick N, Forette F, Hadler D, et al. Protocols to demonstrate slowing of Alzheimer disease progression. Position paper from the International Working Group on Harmonization of Dementia Drug Guidelines. The Disease Progression Sub-Group. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 3):50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings JL, Zhong K. Clinical trials and drug development in neurodegenerative diseases: unifying principles. In: Cummings JL, Pillai JA, editors. Neurodegenerative Diseases Unifying Principles. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2017. pp. 323–336. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams MM, Storandt M, Roe CM, Morris JC. Progression of Alzheimer’s disease as measured by Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes scores. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:S39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz R. Biomarkers and surrogate markers: an FDA perspective. NeuroRx. 2004;1:189–195. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wessels AM, Siemers ER, Yu P, et al. A combined measure of cognition and function for clinical trials: The integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (iADRS) J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2015;2:227–241. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Logovinsky V, Hendrix SB, et al. ADCOMS: a composite clinical outcome for prodromal Alzheimer’s disease trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee For Medicinal Products For Human Use. Qualification opinion of low hippocampal volume (atrophy) by MRI for use in clinical trials for regulatory purpose - in pre-dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease.: European Medicines Agency. [updated 06 Dec 2016 December 6, 2016];2011 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/includes/document/document_detail.jsp?webContentId=WC500116264&mid=true.

- 24.European Medicine Agency; Committee For Medicinal Products For Human Use. Qualification opinion of novel methodologies in the predementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease: cerebro-spinal fluid related biomarkers for drugs affecting amyloid burden. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.003. EMA/CHMP/SAWP/102001/2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amur SG, Sanyal S, Chakravarty AG, et al. Building a roadmap to biomarker qualification: challenges and opportunities. Biomark Med. 2015;9:1095–1105. doi: 10.2217/bmm.15.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu E, Schmidt ME, Margolin R, et al. Amyloid-beta 11C-PiB-PET imaging results from 2 randomized bapineuzumab phase 3 AD trials. Neurology. 2015;85:692–700. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008;372:216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novak G, Fox N, Clegg S, et al. Changes in brain volume with bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;49:1123–1134. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox NC, Black RS, Gilman S, et al. Effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) on MRI measures of cerebral volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:1563–1572. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159743.08996.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Fagan AM. Fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006221. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mega MS, Dinov ID, Porter V, et al. Metabolic patterns associated with the clinical response to galantamine therapy: A fludeoxyglucose f 18 positron emission tomographic study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.5.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medeiros R, Baglietto-Vargas D, LaFerla FM. The role of tau in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:514–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cummings JMT, Lee G. Alzheimer’s drug development pipeline: 2016. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2016;2:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]