Abstract

States play a key role in addressing obesity and its risk factors through policymaking, but there is variation in state activity nationally. The goal of this study was to examine whether the presence of a consolidated Democratic or Republican “trifecta”– when a state’s governorship and both houses of the legislature are dominated by the same political party– or divided government (i.e., without a trifecta) is associated with obesity-related policy content and enactment. In 2016 and 2017, we gathered state bills and laws utilizing the CDC Chronic Disease State Policy Tracking System, and examined the association between state-level political party control and the enactment of state-level obesity-related policies in all states during 2009–2015. The three areas of interest included: policies specifically addressing obesity, nutrition, or physical activity in communities, schools, or workplaces using a public health framework; neutral policies, such as creating government task forces; and policies that employed a business-interest framework (e.g., Commonsense Consumption Acts that prohibit consumer lawsuits against restaurant establishments). Using divided governments as the reference group, we found that states with Democratic trifectas enacted significantly more laws, and more laws with a public health framework. Republican trifecta states enacted more laws related to physical activity, and in some states like Texas, Republican trifectas were exceptionally active in passing policies with a public health framework. States with Republican trifectas enacted a statistically similar amount of laws as states with divided governments. These findings suggest promise across states for obesityrelated public health policymaking under a variety of political regimes.

Introduction

Obesity, poor nutrition, and physical inactivity are major risk factors for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, which are among the leading causes of death and disability in the U.S.1, 2 State governments have sought to address these issues through various policy levers, but there is wide variation among the states in the amount and type of laws enacted. This may reflect varying electoral and political party support for certain policies.3 Previous research points to divisions along political party lines supporting a “personal responsibility” approach versus a multi-sectoral approach focusing on nutrition and physical activity in communities, schools, or workplaces.4, 5 These differences may also reflect varying importance placed on public health as opposed to business interests.6

Previous research analyzed predictors of states passing obesity-related legislation, including political influences, although this literature is inconsistent depending on the specific exposure examined. Examining childhood obesity-related legislation passed in 2003–2005, Cawley and Liu found states with Democratic governors or legislatures not controlled by Republicans enacted more laws,7 while Boehmer et al. found having bipartisan sponsorship and Democratic control of both chambers were associated with law enactment.8 Eyler et al. found that childhood obesity laws were more likely to be enacted during 2006–2009 when introduced with bipartisan and Republican sponsors, relative to Democratic sponsors.9 Marlow found that law enactment between 2001–2010 focusing on preventing childhood and adult obesity, was unrelated to the political party affiliation of the governor or each house of the state legislature, assessed individually.10 Donaldson et al. examined state and bill characteristics associated with the enactment of adult obesity prevention legislation introduced in 2010–2013 and found a greater proportion of Republican-sponsored bills were enacted than those introduced by others.11

These prior studies reveal that state political control may be associated with the enactment of obesity-related legislation. In the current study, we build on this literature by examining a different operationalization of state political power– the presence of a consolidated Republican or Democratic “trifecta,” in which a state’s governorship and both houses of the legislature are all dominated by the same political party, or divided government (i.e., the absence of a trifecta), is associated with obesity-related policy passage and content. A trifecta may play a decisive role in the legislative process because one political party has functional control over the state government and ostensibly determines the direction of state policymaking.12 The 2016 election resulted in 25 Republican trifectas, six Democratic trifectas and 19 states with a divided government.12 Thus, it is important to examine how state political party consolidation influences state-level public health policymaking. The present study will provide information for practitioners and advocates regarding whether trifectas influence state adoption of specific types of obesity-related policies.

We tested the trifecta hypothesis by examining policies pertaining to obesity, nutrition, and physical activity, proposed or passed during 2009–2015 across all 50 states. Based on prior work,3–6, 13–15 we hypothesized that laws with a public health framework would more likely be enacted under a Democratic trifecta, more laws with business-interest framework would pass under Republican trifectas, and that less legislative activity would take place under a divided government. Our findings provide an evidence-based understanding of whether and how consolidation of political party control is associated with the enactment of obesity-related policy.

Methods

Legislative Data

Legislative data were gathered from all 50 states (not including Washington, D.C.) using the CDC’s Chronic Disease State Policy Tracking System (CDSPT) in 2016.16 The CDC systematically identified bills and laws using a set of 49 search strings; its full methodology is described elsewhere.17 Using this database, we collected state legislation for the years 2009–2015.

The term “legislation” includes bills and laws; bills are proposed pieces of legislation while laws are enacted pieces of legislation. To identify which pieces of legislation were relevant to our study, the team evaluated the abstracts provided by CDSPT according to whether the policy focused on obesity or explicitly addressed risk factors for obesity, nutrition or physical activity, or the environments in which these risk factors take place (e.g., urban planning). Three researchers reviewed the abstracts of all 4,628 bills and laws introduced or enacted in 2009–2015; 2,461 were deemed potentially relevant. The most recent version of the bill or law was retrieved using the official websites of the state legislatures, the bill tracking website LegiScan,18 or the legal research tool LexisNexis.

Exposure

The primary exposure variable was the political party in control of the governorship, house, and senate. Political party control was classified as Republican, Democratic, or “divided” for each of the 50 states in each of the seven years of the study period.12

Classification and Coding

Variables of interest were coded using the software REDCap (Nashville, Tennessee).19,19 The coding instrument was initially piloted with double entry of a small subset of policies to ensure an acceptable level of intercoder reliability (i.e., an interclass correlation coefficient of at least 0.75). Each piece of legislation was then coded by one of two coders; another investigator conducted random and targeted checks to ensure accuracy.

Coders abstracted several types of information from the legislation, whether: it was a bill or law; addressed obesity, a risk factor for obesity, or both; and whether the policy specifically intended to address obesity or a risk factor, or whether these would be a potential side effect of the law (e.g., by establishing bicycle lanes for safety purposes). Each piece of legislation was then categorized according to which policy topic(s) it addressed. Multiple policy topics could be addressed by a single piece of legislation.

There were three categories of policy topics. First, “core public health” legislation specifically furthered a public health framework, where legislators sought to improve obesity, nutrition, or physical activity across three settings: communities, schools, or worksites. We separately coded whether legislation proposed a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax, as this is a recent policy topic of interest.

Second, coders identified topics that employed a “business interest” framework, such as by: protecting food retailers (e.g., under Commonsense Consumption Acts (CCAs) which prohibit consumer lawsuits claiming that restaurant food caused chronic disease), disincentivizing healthy behaviors (e.g., taxing gym memberships), or reducing the authority of local governments to enact core public health policies through preemption. Preemption is when a higher level of government (here, the state) withdraws or limits the ability of a lower level of government to act on a particular issue.

Third, we coded legislation that addressed “neutral” topics, such as those relating to general school wellness programs, creating an obesity-related task force, amending food assistance programs, and targeting health insurance to address obesity or a risk factor. We categorically excluded as irrelevant full state budget and appropriations bills. The full coding instrument is in the Supplement.

Data Analysis

We identified the percent of the time that there was Republican, Democratic, or divided party control overall and for each state, to establish the variation in consolidation of political party control. In the case of Nebraska, which has a unicameral legislature, we considered control of both the governorship and the legislature as a trifecta.12

In 2017, we characterized the sample of bills and laws, and then engaged in deeper analysis of the laws alone. In these analyses, enactment of laws by Republican and Democratic trifectas was compared to enactment under divided governments (the reference group). For these, we examined the association between consolidation of state political party control and the number of total, public health framework, and business interest framework laws, using linear regressions. We also determined the association between political party control and law content using logistic regressions, with the exception of policy topics with a business framework because of the small sample size. Finally, we examined the distribution of laws by state, although small sample sizes precluded the evaluation of statistical significance in these descriptive analyses. Analyses were conducted in StataMP 14 (College Station, Texas) and R 3.2.1 (Vienna, Austria).

Because obesity prevalence may be correlated with state political party control, in secondary analyses we additionally controlled for time-varying state-level obesity prevalence to reduce possible confounding. Obesity prevalence data were constructed using nationally representative survey data from the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.20

Results

Legislation Characteristics

There were 1705 total pieces of legislation, including 262 laws between 2009 and 2015 (Table 1). The rate of law enactment was 15.4%, similar to that in prior studies.8, 11, 21 The 262 laws addressed 367 policy topics, i.e., an average of 1.4 topics per law. Five percent of these laws address obesity alone, 71% addressed a risk factor for obesity, and 24% addressed both obesity and a risk factor. There were 249 laws that addressed core public health policy topics, in which 309 separate policy topics were included. The largest portion of these laws (40%) sought to improve community nutrition, followed by laws seeking to promote physical activity in the community (26%), improve nutrition in schools (21%), and promote physical activity in schools (18%). More laws addressed the community than schools (187 versus 112 policy topics), and very few laws addressed workplaces (10 policy topics).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Obesity-Related Legislation

| Legislation Proposed |

Laws Passed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1,705 | N = 262 | |||

| Variable | Mean/% | N | Mean/% | N |

| Explicitly targets obesity | 0.243 | 414 | 0.271 | 71 |

| Intentionally health-focused | 0.751 | 1280 | 0.733 | 192 |

| Relevance to obesity | ||||

| Addresses obesity only | 0.055 | 94 | 0.05 | 13 |

| Addresses risk factor only | 0.752 | 1282 | 0.714 | 187 |

| Address obesity and risk factor | 0.192 | 327 | 0.237 | 62 |

| Topics addressed | ||||

| Core public health framework | 0.961 | 1639 | 0.95 | 249 |

| Community: Improving nutrition | 0.45 | 767 | 0.401 | 105 |

| Community: Promoting physical activity | 0.194 | 331 | 0.256 | 67 |

| Community: Addressing obesity | 0.059 | 100 | 0.057 | 15 |

| Schools: Improving nutrition | 0.216 | 368 | 0.214 | 56 |

| Schools: Promoting physical activity | 0.185 | 315 | 0.176 | 46 |

| Schools: Addressing obesity | 0.053 | 90 | 0.038 | 10 |

| Workplace: Improving nutrition | 0.009 | 15 | 0.012 | 3 |

| Workplace: Promoting physical activity | 0.012 | 21 | 0.027 | 7 |

| Workplace: Addressing obesity | 0.008 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Business interest framework | 0.031 | 52 | 0.031 | 8 |

| Legal | 0.009 | 15 | 0.012 | 3 |

| Preemption: Nutrition-related | 0.017 | 29 | 0.015 | 4 |

| Preemption: Physical activity related | 0.003 | 5 | 0.004 | 1 |

| Helping food companies | 0.002 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Other/Neutral framework | ||||

| Community: Soda or SSB tax | 0.034 | 58 | 0.004 | 1 |

| Support for a school wellness program/policy | 0.024 | 41 | 0.019 | 5 |

| Health insurance plan changes | 0.023 | 39 | 0.012 | 3 |

| Gov't task force, council, resolution, or study | 0.116 | 198 | 0.164 | 43 |

| Requesting state gov't to support/amend food program | 0.013 | 22 | 0.008 | 2 |

| Requesting federal gov't to support/amend food program | 0.019 | 33 | 0.015 | 4 |

| Number of topics addressed per bill/law | 1.445 | 1.431 | ||

| Political party consolidation when proposed/passed | ||||

| Republican trifecta | 0.238 | 406 | 0.298 | 78 |

| Democratic trifecta | 0.359 | 612 | 0.378 | 99 |

| Divided | 0.403 | 687 | 0.324 | 85 |

| Law | 0.154 | 262 | ||

Note: Legislation (first column) includes both bills proposed and laws passed. Multiple topics can be addressed in a single document.

There were 44 bills and eight laws containing policy topics focusing on a business interest framework. Of the laws that passed, four preempted legislation related to nutrition or physical activity and three were CCAs.

Consolidation of State Political Party Control

Of the 350 state-year observations during the study period, there were 220 in which a relevant bill was proposed or law was enacted. During the 220 state-year observations in the data set, there were 65 (29.6%) Democratic trifectas, 70 (31.8%) Republican trifectas, and 85 (38.6%) with divided party control. There was substantial variation in political party control by state during the seven year period (Supplemental Figure 1). One state (Delaware) had a Democratic trifecta, eight states had a Republican trifecta, and four states were under divided party control for all seven years of the study. The remaining 37 states had at least two types of political party control during the study period.

Association between State Political Party Control and Law Characteristics

Republican trifectas enacted 78 laws with 72 of them addressing core public health topics (Table 2). Democratic trifectas passed 99 laws, with 93 of them related to the core public health topics. States with divided governments enacted 85 laws, with 84 related to core public health topics. Across all three government types, there were similar percentages of activity focused on addressing obesity (~5%), a risk factor for obesity (~71%), or both obesity and a risk factor (~23%). Moreover, the majority of the legislative activity for all government types centered on five policy domains: improving nutrition in the community and schools, promoting physical activity in the community and schools, and establishing a government task force. Four of the laws with a business interest framework were enacted by Republican trifectas during the study period, while Democratic trifectas and divided states each enacted two.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Laws Passed, By State Government Consolidation

| Republican | Democratic | Divided | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean/% | N | Mean/% | N | Mean/% | N |

| Explicitly targets obesity | 0.256 | 20 | 0.283 | 28 | 0.271 | 23 |

| Public health framework | 0.769 | 60 | 0.687 | 68 | 0.753 | 64 |

| Relevance to obesity | ||||||

| Addresses obesity | 0.051 | 4 | 0.051 | 5 | 0.047 | 4 |

| Addresses risk factor | 0.718 | 56 | 0.717 | 71 | 0.706 | 60 |

| Address obesity and risk factor | 0.231 | 18 | 0.232 | 23 | 0.247 | 21 |

| Topics addressed | ||||||

| Core public health framework | ||||||

| Community: Improving nutrition | 0.308 | 24 | 0.434 | 43 | 0.447 | 38 |

| Community: Promoting physical activity | 0.333 | 26 | 0.232 | 23 | 0.212 | 18 |

| Community: Addressing obesity | 0.077 | 6 | 0.04 | 4 | 0.059 | 5 |

| Schools: Improving nutrition | 0.154 | 12 | 0.182 | 18 | 0.306 | 26 |

| Schools: Promoting physical activity | 0.192 | 15 | 0.202 | 20 | 0.129 | 11 |

| Schools: Addressing obesity | 0.051 | 4 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.047 | 4 |

| Workplace: Improving nutrition | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Workplace: Promoting physical activity | 0.013 | 1 | 0.04 | 4 | 0.024 | 2 |

| Workplace: Addressing obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Health insurance plan changes | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.012 | 1 |

| Business interest framework | ||||||

| Legal | 0.039 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Preemption: Nutrition-related | 0.013 | 1 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.012 | 1 |

| Preemption: Physical activity related | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.012 | 1 |

| Other/Neutral framework | ||||||

| Community: Soda or SSB tax | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.012 | 1 |

| Schools: Support for a school wellness program/policy | 0.013 | 1 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.012 | 1 |

| Gov't task force, council, resolution, or study | 0.154 | 12 | 0.182 | 18 | 0.153 | 13 |

| Requesting state gov't to support/amend food program | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.012 | 1 |

| Requesting federal gov't to support/amend food program | 0.013 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.024 | 2 |

| Core public health topics addressed | 0.923 | 72 | 0.939 | 93 | 0.988 | 84 |

| Business interest topics addressed | 0.051 | 4 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.024 | 2 |

| Number of topics addressed per policy | 1.359 | 1.455 | 1.471 | |||

| Number of laws | 78 | 99 | 85 | |||

| Number of state-year observations (i.e., years in control) | 70 | 65 | 85 | |||

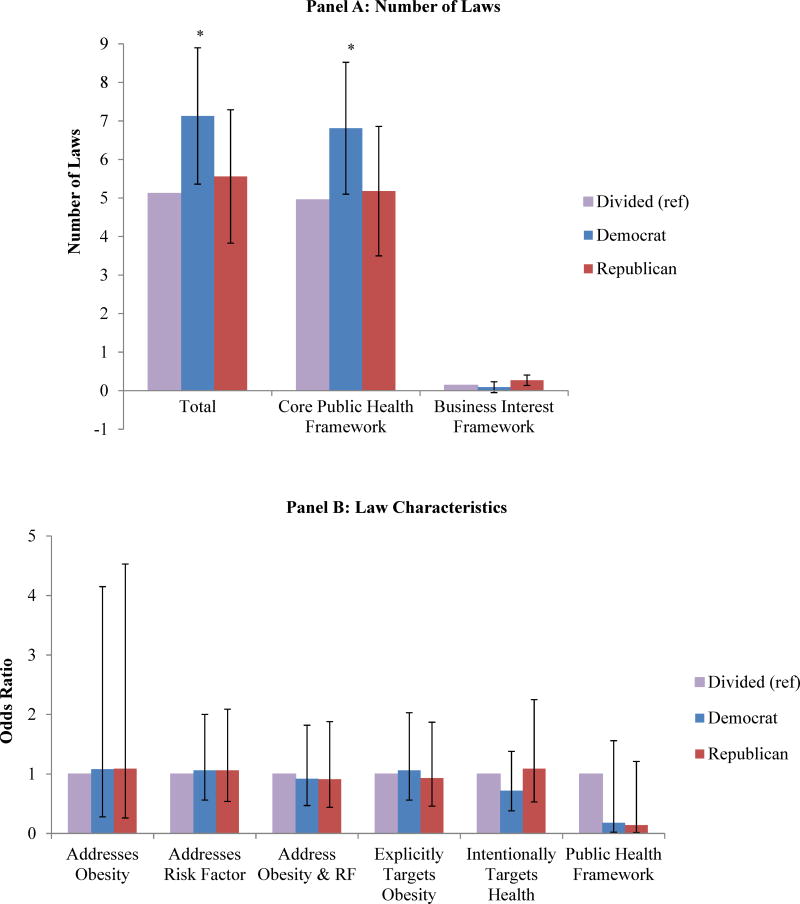

Democratic trifectas passed an average of 2.01 more laws relative to states with divided governments (95% CI: 0.24, 3.78), and specifically an average of 1.86 more core public health laws (95% CI: 0.15, 3.58) (Figure 1A). Law characteristics did not differ by consolidation of political party control (Figure 1B). In terms of law content, Republicans were more likely to pass laws related to physical activity (OR 2.51, 95% CI: 1.32, 4.74) and were less like to enact laws related to nutrition than divided governments (OR 0.42, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.79) (Figure 1C). The small number of business framework laws precluded the determination of statistical significance by government type.

Figure 1. Association between Consolidation of State Political Party Control and Passage of Obesity-related Laws.

Note: N = 262 laws passed during 220 state-year periods. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The symbol * indicates that the value is statistically significantly different from the Divided reference group at a p-level of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using linear (Panel A) or logistic (Panels B and C) regressions. Tabular results are available in Supplemental Tables 1–3. Laws with a business interest framework were not included in Panel B due to the very large confidence intervals.

Additionally adjusting for obesity prevalence did not substantially alter the size or statistical significance levels of these coefficients. Moreover, in these analyses, obesity prevalence itself was not associated with the number of laws or law characteristics, except that higher obesity prevalence was associated with a decrease in the odds of obesity-related legislation (OR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.98) (data available upon request).

State Variation in Legislation

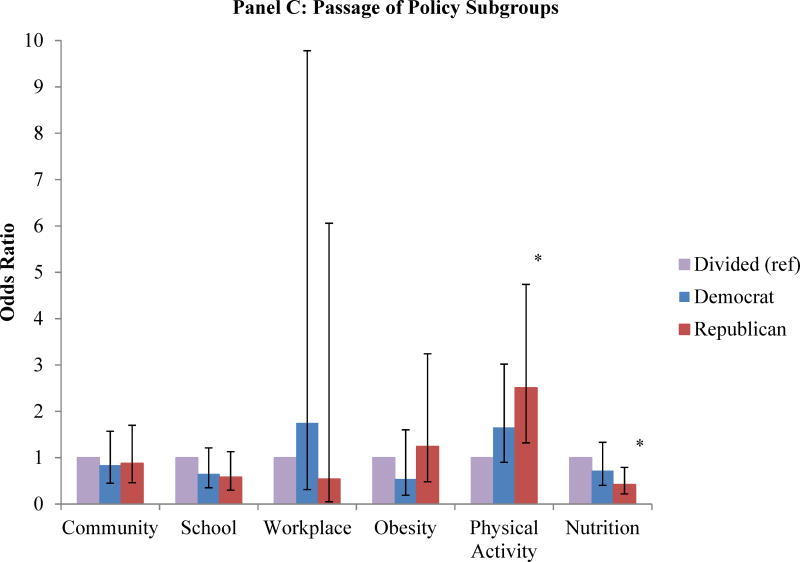

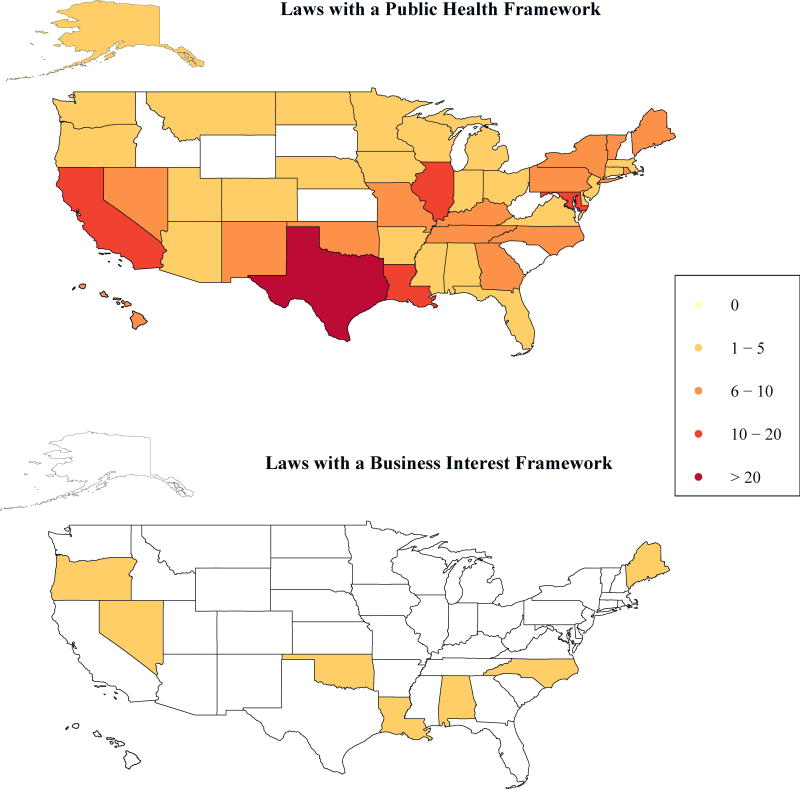

There was also variation in the number and types of policies passed by state (Figure 2). Texas passed the most core public health laws (25 laws) while having Republican trifectas for all seven years. The states that enacted the next most number of laws were Illinois, Maryland, and California (18, 16, and 12, respectively), under a mix of divided and Democratic trifectas. The states that established the most government task forces were Texas (eight), Illinois (eight), and Louisiana (five) (data available upon request). Three states enacted CCA laws over the study period: Alabama, North Carolina, and Oklahoma, all under Republican trifectas.

Figure 2. Number of Obesity-Related Laws, by State (2009−2015).

Note: N = 262 laws were identified using the Chronic Disease State Policy Tracking System provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and include those that address obesity, nutrition, or physical activity.

Seven states did not pass any obesity-related legislation: Idaho, Kansas, New Hampshire, South Carolina, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wyoming. There was not a consistent government type present in these states during the study period.

Of note, we found 57 SSB tax bills proposed in 22 states, with eleven of these in Hawaii. The single SSB law that passed was in Tennessee in 2011, extending a temporary soft drink bottle tax to fund anti-littering programs.22

Discussion

This study examines the association between state political characteristics and the passage of obesity-related policies, and to our knowledge is the first to operationalize consolidation of state political party control as the exposure of interest in this context, while also examining probusiness laws. We found that Democratic trifectas enacted significantly more laws, and particularly more core public health laws. Yet, Republicans enacted significantly more laws related to physical activity, and in some states like Texas, Republican trifectas were exceptionally active in passing legislation with a public health framework. These analyses were robust in the inclusion of obesity prevalence as an additional control. It is an important finding for public health that divided governments enacted a similar amount of core public health laws as states with Republican trifectas. This could indicate that in those states, divided governments are capable of achieving compromise, or it could indicate that the public health problems are pressing enough for the parties to work together and achieve bipartisan consensus. These patterns suggest promise for public health policymaking under a variety of political regimes.

Previous studies that assessed the political parties of the governor, senate, and house individually found that having a Democratic governor or non-Republican legislature was associated with law enactment,7 or alternatively that there was no association between political party affiliation and law enactment.10 This is similar to our findings that Democratic trifectas enact a greater number of public health policies, and that divided governments were as active as Republican trifectas. Moreover, our finding that Republican trifectas enacted more laws supporting physical activity in communities and schools challenges notions that there is little Republican support for such multi-sectoral approaches;5 but, it could also be argued that a focus on physical activity over nutrition aligns with a personal responsibility framework.4 Additional studies examined the political party of the bill sponsor, which is a different type of exposure than the current study, so are not directly comparable.

The current study also found that states with all three government types enacted laws supporting nutrition and physical activity in communities and schools, which aligns with the Institute of Medicine’s 2012 recommendations to accelerate progress in obesity prevention.2 States enacted fewer laws directly targeting obesity in the workplace; this corresponds with previous research indicating that certain states support workplace wellness programs more generally, rather than focusing on specific health topics.23 Also, although the creation of government task forces is often thought of as a method to avoid meaningful policymaking, we found that the three states that established the most task forces – Texas, Illinois, and Louisiana – were also among the most active states enacting core public health laws. Finally, states that did not enact public health laws under a trifecta may have lacked legislators (or constituents) interested in this topic area, and thus did not take advantage of their trifecta position,15 rather than facing a predetermined barrier imposed by a specific political makeup.

The current study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it uniquely analyzed consolidated political party control and included legislation that supported both public health and business interest frameworks. Second, it analyzed legislation addressing obesity and its risk factors for children and adults, spanning seven years that included one presidential and two midterm elections. Further, unlike previous work that categorized each law as addressing a single topic, the coding schema for this study allowed multiple policy topics to be addressed by a single bill or law, which is more consistent with how policymaking often proceeds.

This study has several limitations. First, although our exposure of interest is consolidation of political party control, there may be other factors that determine both political consolidation and obesity-related policymaking – such as macroeconomic forces or population health characteristics – that confound the findings we observe here; future studies should explore this possibility. Second, this study did not measure state super-majorities, federal or local legislation, or agency regulations at any level of government. Local governments, in particular, have been on the forefront of enacting obesity-related legislation and future research should consider how political party control influences local policy passage and content, and how local legislation correlates with state-level legislation within states. Third, the CDC changed its data collection protocol in 2011,24 which narrowed the search string for later years. This change applied to all states so did not introduce bias into our findings, but it prevented analysis of policy trends over time. Fourth, this study did not specifically address whether certain policies enjoy bipartisan support, whether certain problems are sufficiently compelling to overcome political differences, or whether there are political nuances in states under a divided government that increase bipartisan policymaking. Future research should examine these questions. Lastly, the CDSPT did not include all business-interest legislation of interest. For example, this study found 34 pieces of legislation that contained preemptive language and only five laws, most of which were clauses in broader pieces of legislation relevant to the CDSPT’s primary search terms. Significantly, CDSPT did not capture several laws enacted under Republican trifectas during the study period which solely preempted the ability of local governments to address nutrition.25 For example, in 2013, Mississippi preempted local governments from regulating food retail establishments’ provision of nutrition information, incentive items, or enacting laws based upon health disparities;26 and Wisconsin prohibited local governments from restricting food sales based on nutrition criteria or portion size.27 Preemptive laws such as these undermine local determination, grassroots movements, and the enactment of beneficial public health efforts.28 Future research should comprehensively analyze all such business-interest laws using a different legislative database.

Conclusions

This study finds that core public health laws related to obesity were enacted in states under both Republican and Democratic trifectas and under divided governments, although in different quantities and with different policy focuses. This is especially important as the country enters an era with potentially decreased federal interest in public health legislation and in which the majority of states have Republican trifectas and divided governments.29 This study supports the proposition that enacting public health legislation across state political regimes remains feasible. Thus, it may be useful for practitioners and advocates to educate policymakers on the efficacy of public health policies regardless of the political makeup of the state government.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sanjay Basu, MD, PhD, for his helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript and Farah B. Sayad and Karen Caruso for their research assistance.

Financial disclosure: This research was supported in part by the Stanford Child Health Research Institute, the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, as well as the Stanford Clinical and Translational Science Award (grant number UL1 TR001085). The funder played no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the findings for publication. Dr. Hamad is supported by a grant from the National Heart Lung Blood Institute (grant number K08 HL132106).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. 2017 Apr 10; 2017 Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch PJ, Dake JA, Price JH, Thompson AJ, Ubokudom SE. State legislators' support for evidence-based obesity reduction policies. Preventive medicine. 2012;55(5):427–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kersh R. The politics of obesity: a current assessment and look ahead. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):295–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin ME, McCarthy WJ. The association between county political inclination and obesity: results from the 2012 presidential election in the United States. Preventive medicine. 2013;57(5):721–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robles B, Kuo T. Predictors of public support for nutrition-focused policy, systems and environmental change strategies in Los Angeles County, 2013. BMJ open. 2017;7(1):e012654. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cawley J, Liu F. Correlates of State Legislative Action to Prevent Childhood Obesity. Obesity. 2008;16(1):162–167. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boehmer TK, Luke DA, Haire-Joshu DL, Bates HS, Brownson RC. Preventing Childhood Obesity Through State Policy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(4):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eyler AA, Nguyen L, Kong J, Yan Y, Brownson R. Patterns and Predictors of Enactment of State Childhood Obesity Legislation in the United States: 2006–2009. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(12):2294–2302. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marlow ML. Determinants of state laws addressing obesity. Applied Economics Letters. 2014;21(2):84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaldson EA, Cohen JE, Villanti AC, Kanarek NF, Barry CL, Rutkow L. Patterns and predictors of state adult obesity prevention legislation enactment in US states: 2010–2013. Preventive Medicine. 2015;74(0):117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucy Burns Institute. Ballotpedia: The Encyclopedia of American Politics. 2017 Apr 10; 2017 Available from: https://ballotpedia.org/

- 13.Kohut A, Doherty C, Dimock M, Keeter S. Partisan Polarization Surges in Bush, Obama Years. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center for the People and the Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartels LM, Jacobson GC. Polarization, gridlock, and presidential campaign politics in 2016. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2016;667(1):226–246. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pallay G. Who Runs the States. 2014 Apr 10; 2017 Available from: https://ballotpedia.org/Ballotpedia:Who_Runs_the_States.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control. Chronic Disease State Policy Tracking System. 2017 Apr 10; 2017 Available from: https://nccd.cdc.gov/CDPHPPolicySearch.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control. State legislative and regulatory action to prevent obesity and improve nutrition and physical activity. Atlanta, Georgia: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.LegiScan. LegiScan: Bringing People to the Process. 2017 Apr 10; 2017 Available from: https://legiscan.com/

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, Georgia: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lankford T, Hardman D, Dankmeyer C, Schmid T. Analysis of state obesity legislation from 2001 to 2010. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2013;19:S114–S118. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182847f2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tennessee Legislature. Senate Bill 2551. An act to amend Tennessee Code Annotated, Section 57-5-201(a)(2) and Section 67-4-402(b)(1) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pomeranz JL, Garcia AM, Vesprey R, Davey A. Variability and Limits of US State Laws Regulating Workplace Wellness Programs. American journal of public health. 2016;106(6):1028–1031. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKinstry J. In: Personal communication. Pomeranz Jennifer L., editor. Centers for Disease Control; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arizona Legislature. Arizona Revised Statues Annotated, § 44-1380 Retail Food Establishments. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mississippi Legislature. Senate Bill 2687. An act to reserve to the legislature any regulation of consumer incentive items and nutrition labeling for fod that is a menu item in restaurants, food establishments, and vending machines. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wisconsin Legislature. Wisconsin Statutes Annotated § 66.0418. Prohibition of local regulation of certain foods, beverages. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pomeranz JL, Pertschuk M. A Significant and Quiet Threat to Public Health in the United States: State Preemption. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;(0):e1–e3. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boozary AS, Nutt CT. President Donald Trump Is a Threat to Public Health. 2017 Apr 10; 2017 Available from: http://harvardpublichealthreview.org/the-inauguration-of-donald-trump/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.