Abstract

Identifying predictors of persistence and recurrence of depression in individuals with a major depressive episode (MDE) poses a critical challenge for clinicians and researchers. We develop using a nationally representative sample, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; N=34,653), a comprehensive model of the 3-year risk of persistence and recurrence in individuals with MDE at baseline. We used structural equation modeling to examine simultaneously the effects of four broad groups of clinical factors on the risk of MDE persistence and recurrence: 1) severity of depressive illness, 2) severity of mental and physical comorbidity, 3) sociodemographic characteristics and 4) treatment-seeking behavior. Approximately 16% and 21% of the 2,587 participants with an MDE at baseline had a persistent MDE and a new MDE during the 3-year follow-up period, respectively. Most independent predictors were common for both persistence and recurrence and included markers for the severity of the depressive illness at baseline (as measured by higher levels on the general depressive symptom dimension, lower mental component summary scores, prior suicide attempts, younger age at onset of depression and greater number of MDEs), the severity of comorbidities (as measured by higher levels on dimensions of psychopathology and lower physical component summary scores) and a failure to seek treatment for MDE at baseline. This population-based model highlights strategies that may improve the course of MDE, including the need to develop interventions that target multiple psychiatric disorders and promotion of treatment seeking to increase access to timely mental health care.

Keywords: depression, depressive disorder, persistence, recurrence, relapse, course

Introduction

Major depression is a leading source of disease burden (Hollon et al., 2005; Lopez et al., 2006) characterized by complex patterns of recurrence and persistence (Hasin et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2003; Mueller et al., 1999; Solomon et al., 1997). Persistence and recurrence are common among patients with major depression (Frank et al., 1990; Keller et al., 1983; Mueller et al., 1999). Persistence may be defined by a prolonged time to recovery from an index episode and recurrence by the occurrence of a new episode in a remitted case (Skodol et al., 2011). Identifying predictors of persistence and recurrence in patients with a major depressive episode (MDE) is an important challenge for clinicians and researchers.

Prior research has implicated several risk factors for MDE persistence or recurrence. They include severity of major depression (Sargeant et al., 1990; Skodol et al., 2011; Spijker et al., 2010; Steinert et al., 2014), number of lifetime MDEs (Skodol et al., 2011; Spijker et al., 2010, Steinert et al., 2014), co-occurring Axis I (Hoertel et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2013c; Keller et al., 1982, 1992; Klein et al., 2006; Manetti et al., 2014; Steinert et al., 2014) and Axis II disorders (Grilo et al., 2005; Skodol et al., 2011), history of suicide attempts (Avery and Winokur, 1978), family history of depression (Patten et al., 2010), concurrent physical health problems and psychosocial difficulties (Lam et al., 2009), early age at onset of first MDE (Hoertel et al., 2013a; Klein et al., 1999), stressful live events (Wang et al., 2012), female gender, older age and being divorced or widowed (Colman et al., 2011; Dowrick et al., 2011; Fava et al., 2007; Gilman et al., 2013; Hardeveld et al., 2013a, 2013b; Kornstein et al., 2000; Lam et al., 2009; Patten et al., 2012; ten Doesschate et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012).

The diversity of these predictors and their frequent co-occurrence suggest the need to develop more powerful statistical approaches. Several integrative predictive models of MDE persistence or recurrence have been examined (Brugha et al., 1997; Dowrick et al., 2011; ten Doesschate et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014; Fandiño-Losada et al., 2016). However, most of these models have been based on samples of convenience and used relatively small sample sizes. In addition, because MDE often co-occurs with other mental disorders (Kessler et al., 2003, 2005; Manetti et al., 2014), recent theories have proposed a meta-structure of psychiatric diagnoses that organizes disorders into broad dimensions of psychopathology (i.e., internalizing and externalizing dimensions) (Blanco et al., 2013; Eaton et al., 2012; Hoertel et al., 2015a, 2015b; Kotov et al., 2011; Krueger et al., 1998; Krueger and Markon, 2006). Applying this dimensional approach to model disorder comorbidity in a comprehensive model of MDE persistence or recurrence could help clarify whether broad psychopathological liabilities or individual Axis I or Axis II disorders predict persistence or recurrence of MDE.

This report proposes a comprehensive model of the 3-year risk of persistence or recurrence of MDE using a longitudinal nationally representative study, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). We used structural equation modeling to examine simultaneously the effects of four broad groups of clinical factors previously identified as potential predictors of persistence and recurrence of MDE: 1) severity of depressive illness, 2) severity of mental and physical comorbidity, 3) sociodemographic characteristics and 4) treatment-seeking behavior. With this model, we aimed to ascertain readily identifiable characteristics to help clinicians recognize adults with MDE who are at increased risk for recurrent or chronic MDE.

Method

Sample

Data were drawn from the wave 1 and wave 2 of the NESARC, a nationally representative face-to-face survey of the US adult population, conducted in 2001–2002 (Wave 1) and 2004–2005 (Wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) (Grant et al., 2003). The target population included the civilian noninstitutionalized population, aged 18 years and older, residing in the United States. The overall response rate at Wave 1 was 81% and the cumulative response rate at Wave 2 was 70.2%, resulting in 34,653 Wave 2 interviews (Grant et al., 2009). The Wave 2 NESARC data were weighted to adjust for non-response, demographic factors and psychiatric diagnoses, to ensure that the Wave 2 sample approximated the target population, that is, the original sample minus attrition between the two waves (Grant et al., 2009). The research protocol, including written informed consent procedures, received full human subjects review and approval from the U.S. Census bureau and the Office of Management and Budget. The present analysis includes the 2,587 participants who had a DSM-IV diagnosis of MDE during the year preceding the Wave 1 interview and completed interviews at both waves.

Measures

Assessment of the 3-year risk of persistence and recurrence of MDE

Persistence was defined as meeting full criteria for current MDE at Wave 1 and throughout the entire 3-year follow-up period. Recurrence was defined as meeting full criteria for current MDE at Wave 1 and again during the last 12 months in Wave 2 but not during the first 24 months after the Wave 1 interview (Skodol et al., 2011).

Assessments of DSM-IV past-year Axis I and lifetime Axis II diagnoses at Wave 1

Mental disorders were assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule, DSM-IV version (AUDADIS-IV), a structured diagnostic instrument administered by trained lay interviewers (Grant et al., 2009). In accord with DSM-IV criteria, MDE diagnosis required meeting clinical significance criteria (i.e., distress or impairment), having a primary mood disorder (excluding substance-induced or general medical conditions), and ruling out bereavement. Other Axis I diagnoses included substance use disorders (alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, and nicotine dependence), mood disorders (dysthymic disorder, and bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder), and pathological gambling. For MDE and all Axis I disorders, diagnoses were made in the past 12 months prior to Wave 1. Axis II disorders (including avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, histrionic, paranoid, schizoid, and antisocial personality disorders) were assessed on a lifetime basis (Grant et al., 2009) at Wave 1. The test-retest reliability and validity of AUDADIS-IV measures of DSM-IV mental disorders are good to excellent for substance use disorders and fair to good for major depressive episode and other disorders (Canino et al., 1999; Chatterji et al., 1997; Grant et al., 1995, 2003; Hasin et al., 1997).

Sociodemographic characteristics in Wave 1

Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age, marital status (married vs. non-married), race-ethnicity (White vs. non-White) and household income. In addition, participants were asked about 12 stressful life events concerning a variety of occupational, familial, financial, and legal issues and whether they had experienced these events in the year before the Wave 1 interview (Grant et al., 2003).

Treatment-seeking behavior for major depression

Participants with a current MDE who declared “going anywhere or saw anyone to get help for low mood” during the year preceding the interview were considered as seeking treatment for MDE.

Assessment of prior suicide attempts at Wave 1

To assess a lifetime history of suicide attempts, all individuals with an MDE in the past year of Wave 1 were asked whether they had ever attempted suicide.

Physical and mental health related quality of life

Participants completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12v2), a 12-item measure that assesses life satisfaction and current functioning over the last four weeks. The SF-12v2 can be scored to generate a norm-based physical component summary score (PCS) and a norm-based mental component summary score (MCS). All standardized scale scores range from 0–100 and a mean of 50 (standard deviation = 10); higher scores signify better functioning. The SF-12v2 scale scores have established reliability and convergent validity in community and clinical samples and demonstrate sensitivity to change in clinical status (Rubio et al., 2013, 2014).

Family history of depression

Family history of depression among first degree relatives was ascertained in separate modules of the AUDADIS (Grant et al., 2003). Subjects were prompted with a definition that included examples for depression, and then were asked whether relatives (by category) had experienced this condition. Family history of depression was considered met if the participant reported that any first degree relative had such history (Blanco et al., 2012; Heiman et al., 2008). The test-retest reliability of AUDADIS family history of depression is very good (Grant et al., 2003).

Statistical Analysis

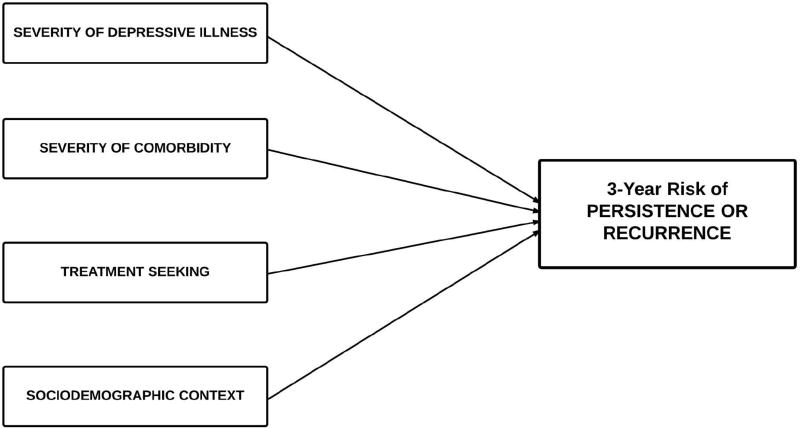

Among participants with a past-year DSM-IV diagnosis of MDE at Wave 1, we first performed a set of bivariate logistic regressions to yield odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and Wald F tests indicating respectively measures of association of each categorical and each continuous putative predictive factor with the 3-year risk of MDE persistence and recurrence (assessed at Wave 2). As indicated in Figure 1, our conceptual model included four groups of predictors: 1) severity of depressive illness, 2) severity of psychiatric and other physical comorbidity, 3) sociodemographic characteristics and 4) treatment-seeking behavior. Severity of depressive illness measures included severity of MDE (measured by latent dimensions underlying MDE symptoms and score on the mental health related quality of life), age at onset of major depression, number of lifetime MDEs, prior suicide attempts and family history of major depressive disorder. Severity of psychiatric and other physical comorbidity was examined using latent dimensions of psychopathology to take into account comorbid disorders and measure of physical health related quality of life. Because predictors of recurrence and persistence of MDE might differ, we performed statistical analyses separately for these two outcomes.

Figure 1.

A conceptual comprehensive model of the 3-year risk of MDE recurrence or persistence in individuals with a twelve-month diagnosis of major depressive episode (MDE) at baseline (N=2,587).

Next, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to identify the latent structure underlying the individual comorbid mental disorders and the latent structure underlying the symptoms of MDE assessed at Wave 1. We built upon the CFA model fit by Blanco et al. (Blanco et al., 2013; Magidson et al., 2014) with these data, which generated 3 dimensions (“internalizing I”, “internalizing II” and “externalizing”) and performed a bifactor CFA model to determine whether a general psychopathology factor measured by all mental disorders in addition to whether disorder-specific factors fit the underlying structure of mental disorders. Second, we performed the CFA model fit by Li et al. (Li et al., 2014), which generated a 3-factor structure of 14 disaggregated DSM-IV symptoms of MDE (see Table 1), to determine whether these three symptom-specific factors fit the underlying structure of depression with our data. We examined measures of goodness-of-fit, including the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker– Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values between 0.90 and 0.95 are considered acceptable, and CFI and TLI values greater than 0.95 and values of RMSEA less than 0.06 indicate good model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Li et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Associations of measures of severity of depressive illness, severity of comorbidity, and sociodemographic characteristics and treatment-seeking behavior with 3-year risk of recurrence and persistence in individuals with a DSM-IV diagnosis of MDE in the past year in Wave 1 (N = 2,587).

| Recurrence (N = 526) |

Persistence (N = 418) |

Remission (N = 1,643) |

Recurrence vs. Remission |

Persistence vs. Remission |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| % (SE) / Mean (SE) |

% (SE) / Mean (SE) |

% (SE) / Mean (SE) |

OR [95%CI] / Wald F (p-value) |

OR [95%CI] / Wald F (p-value) |

|

| Severity of depressive illness | |||||

| Symptoms of MDE | |||||

| Depressed mood | 96.2 (0.9) | 98.7 (0.5) | 95.0 (0.7) | 1.35 [0.78–2.34] | 3.86 [1.76–8.46]**** |

| Anhedonia | 91.8 (1.5) | 92.0 (1.6) | 86.6 (1.1) | 1.74 [1.13–2.69]* | 1.78 [1.11–2.88]* |

| Loss of appetite | 54.9 (2.6) | 58.7 (3.0) | 50.3 (1.5) | 1.20 [0.94–1.54] | 1.40 [1.07–1.84]* |

| Loss of weight | 43.5 (2.9) | 47.2 (3.2) | 39.1 (1.4) | 1.20 [0.92–1.57] | 1.40 [1.05–1.85]* |

| Increase of appetite | 41.5 (2.4) | 39.2 (3.0) | 32.1 (1.4) | 1.50 [1.19–1.89]**** | 1.36 [1.01–1.83]* |

| Increase of weight | 31.8 (2.4) | 34.1 (2.8) | 26.9 (1.4) | 1.27 [0.99–1.64] | 1.41 [1.05–1.88]* |

| Insomnia | 77.6 (2.3) | 80.7 (2.5) | 78.1 (1.4) | 0.97 [0.72–1.31] | 1.17 [0.82–1.66] |

| Hypersomnia | 57.0 (2.7) | 58.1 (3.2) | 44.6 (1.5) | 1.65 [1.29–2.10]**** | 1.72 [1.29–2.29]**** |

| Psychomotor retardation | 48.9 (2.6) | 46.5 (3.2) | 39.9 (1.5) | 1.44 [1.12–1.85]*** | 1.31 [0.99–1.72] |

| Psychomotor agitation | 62.4 (2.4) | 69.0 (2.7) | 56.2 (1.6) | 1.29 [1.02–1.63]* | 1.74 [1.32–2.29]**** |

| Loss of energy or fatigue | 88.0 (1.8) | 88.9 (2.0) | 85.4 (1.1) | 1.25 [0.85–1.82] | 1.36 [0.88–2.12] |

| Feeling of worthlessness | 83.0 (2.2) | 91.3 (1.6) | 76.7 (1.3) | 1.48 [1.05–2.09]* | 3.20 [2.10–4.87]**** |

| Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness | 94.8 (1.4) | 95.4 (1.1) | 90.6 (0.8) | 1.88 [1.05–3.36]* | 2.14 [1.24–3.70]** |

| Recurrent thoughts of death | 73.8 (2.1) | 75.9 (2.9) | 57.1 (1.6) | 2.12 [1.65–2.73]**** | 2.37 [1.72–3.25]**** |

| Past course of major depression | |||||

| Prior Suicide Attempt | 13.8 (1.9) | 25.4 (2.7) | 10.8 (1.0) | 1.33 [0.90–1.96] | 2.83 [2.02–3.95]**** |

| Number of lifetime MDEs | 7.8 (0.7) | 10.6 (1.4) | 5.9 (0.4) | 4.85 (p = .0296) | 10.54 (p = .0015) |

| First degree relative history of depression | 81.5 (1.9) | 77.7 (2.5) | 72.2 (1.5) | 1.70 [1.27–2.26]**** | 1.34 [0.98–1.82] |

| Age at onset of depression | 26.1 (0.7) | 26.6 (0.9) | 29.7 (0.5) | 18.31 (p < 0.0001) | 9.58 (p = 0.0024) |

| Severity of comorbidity | |||||

| Any comorbid disorder | 82.3 (2.0) | 87.1 (1.9) | 72.6 (1.3) | 1.75 [1.31–2.35]**** | 2.56 [1.79–3.66]**** |

| Dysthymia | 16.0 (1.8) | 31.7 (2.8) | 12.9 (1.0) | 1.28 [0.94–1.76] | 3.12 [2.33–4.19]**** |

| Mania/Hypomania | 22.3 (2.4) | 22.0 (2.5) | 14.4 (1.0) | 1.70 [1.25–2.32]**** | 1.67 [1.20–2.33]*** |

| GAD | 21.6 (2.1) | 25.8 (2.9) | 12.3 (1.0) | 1.97 [1.47–2.64]**** | 2.49 [1.77–3.49]**** |

| Panic disorder | 15.3 (1.9) | 19.9 (2.2) | 10.1 (1.0) | 1.60 [1.11–2.30]* | 2.20 [1.58–3.06]**** |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 17.8 (2.0) | 22.1 (2.6) | 9.6 (0.9) | 2.03 [1.46–2.80]**** | 2.67 [1.89–3.76]**** |

| Specific phobia | 24.4 (2.3) | 28.6 (2.6) | 15.6 (1.1) | 1.74 [1.28–2.37]**** | 2.16 [1.61–2.88]**** |

| Alcohol use disorder | 18.4 (2.2) | 13.8 (2.3) | 16.1 (1.2) | 1.18 [0.83–1.67] | 0.83 [0.55–1.28] |

| Drug use disorder | 6.5 (1.3) | 7.8 (1.7) | 5.9 (0.7) | 1.10 [0.68–1.79] | 1.34 [0.79–2.27] |

| Nicotine dependence | 31.8 (2.7) | 35.5 (2.9) | 25.8 (1.4) | 1.34 [1.02–1.76]* | 1.59 [1.20–2.10]*** |

| Pathological gambling | 1.1 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.1) | NA | NA |

| Histrionic PD | 11.6 (1.7) | 8.7 (1.7) | 6.7 (0.8) | 1.82 [1.23–2.68]*** | 1.33 [0.80–2.20] |

| Schizoid PD | 14.1 (2.0) | 25.5 (2.9) | 9.3 (0.9) | 1.60 [1.09–2.35]* | 3.34 [2.33–4.79]**** |

| Paranoid PD | 26.0 (2.3) | 35.1 (3.0) | 15.5 (1.1) | 1.92 [1.42–2.59]**** | 2.96 [2.19–3.99]**** |

| OCPD | 27.0 (2.3) | 29.6 (2.8) | 19.5 (1.4) | 1.53 [1.16–2.01]** | 1.74 [1.24–2.43]*** |

| Dependent PD | 2.0 (1.0) | 6.6 (1.7) | 2.3 (0.5) | 0.86 [0.30–2.46] | 2.97 [1.49–5.90]*** |

| Avoidant PD | 17.9 (2.1) | 26.9 (2.8) | 9.0 (0.9) | 2.20 [1.55–3.12]**** | 3.71 [2.61–5.27]**** |

| Antisocial PD | 11.6 (1.9) | 14.6 (2.3) | 10.6 (1.0) | 1.11 [0.72–1.71] | 1.45 [0.98–2.16] |

| Quality of life | |||||

| 43.8 (0.5) | 37.6 (0.6) | 45.0 (0.3) | 4.50 (p = 0.0359) | 115.58 (p < 0.0001) | |

| Mental component score (MCS) | |||||

| 48.0 (0.6) | 44.6 (0.7) | 48.7 (0.3) | 1.59 (p = 0.2094) | 28.49 (p < 0.0001) | |

| Physical component score (PCS) | |||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 74.8 (2.5) | 72.2 (3.0) | 62.6 (1.6) | 1.77 [1.32–2.37]**** | 1.55 [1.12–2.15]** |

| Men | 25.3 (2.5) | 27.8 (3.0) | 37.4 (1.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 75.2 (2.7) | 78.8 (2.5) | 72.8 (1.8) | 1.14 [0.86–1.50] | 1.39 [1.05–1.84]* |

| Non-White | 24.8 (2.7) | 21.2 (2.5) | 27.2 (1.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 48.2 (2.6) | 47.6 (3.1) | 48.1 (1.5) | 1.00 [0.79–1.27] | 0.98 [0.75–1.29] |

| Not married | 51.9 (2.6) | 52.4 (3.1) | 51.9 (1.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age | 38.0 (0.7) | 40.0 (0.9) | 39.8 (0.5) | 4.93 (p = 0.0282) | 0.04 (p = 0.8383) |

| Household Income ($) | 53290 (8540) | 39370 (2390) | 48830 (1890) | 0.26 (p = 0.6082) | 10.26 (p = 0.0017) |

| Number of 12-month stressful life events (12 events assessed) | 3.1 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.1) | 2.9 (0.1) | 1.59 (p = 0.2103) | 10.24 (p = 0.0018) |

| Seeking Treatment¥ | 48.2 (2.7) | 56.2 (3.2) | 38.7 (1.6) | 1.47 [1.15–1.89]*** | 2.04 [1.53–2.71]**** |

Abbreviations: MDD, major depressive disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OR, odds ratio; PD, personality disorder; OCPD, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder; NA, not applicable.

All Axis I were past year diagnoses while Axis II disorders were assessed on a lifetime basis.

Percentages are weighted to reflect prevalence in U.S. population.

Crude ORs (d.f.=1) indicate measures of association for binary variables and were estimated using logistic regression.

Wald F indicate measures of association for continuous variables and were estimated using linear regression.

This crude association does not take into account of the severity of depressive illness and comorbidity, and sociodemographic characteristics.

p<.001;

p<.005;

p<.01;

p<.05.

ORs and Wald F in bold are statistically significant (p< .05).

Finally, we used a structural equation model with a 3-category multinomial outcome to examine the effect of each predictor on the risk of persistence and recurrence between the two Waves. We used standardized data because they are less affected by the scales of measurement and can be used to evaluate the relative impact of each predictor (Muthen and Muthen, 1998–2006). Standardized estimates of the relationship between persistence or recurrence and each predictor (i.e., direct effects) indicate how many standard deviations higher (or lower) the mean of the latent variable underlying the binary outcome are expected to be for each increase in an additional unit of the predictor while adjusting for all other factors.

To determine if specific comorbid disorders or MDE symptoms predicted persistence or recurrence of MDE above and beyond the association induced by the latent variables and the effects of other factors, modification indices (i.e. chi-square tests with 1 degree of freedom) were examined to test if any of the residuals were correlated with risk of persistence or recurrence. Because of the large sample used and in order to limit type 1 error inflation, statistical significance was evaluated using a two-sided alpha of 0.01. To reduce the risk of including significant direct effects related to multiple testing, we considered significant direct effects of items with modification index greater or equal to 10. All analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 7.2 (Muthen and Muthen, 1998–2006) to account for the NESARC’s complex design. The default estimator for the analysis was the variance-adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV), a robust estimator appropriate for ordered categorical observed variables (Muthen and Muthen, 1998–2006).

Results

Clinical characteristics assessed at wave 1 and the 3-year risk of MDE persistence and recurrence

Among participants with a 12-month DSM-IV diagnosis of MDE at Wave 1 (n=2,587), 15.7% (SE=0.8, N=418) had a chronic MDE and 20.7% (SE=0.9, n=526) had a new MDE during a 3-year follow-up period. Binary logistic models showed that increased risk of MDE persistence was significantly associated with all comorbid mental disorders (except for alcohol and drug use disorders and histrionic and antisocial personality disorders), lower mental and physical component summary scores, all symptoms of MDE (except for insomnia, psychomotor retardation, and loss of energy or fatigue), prior suicide attempts, greater number of lifetime MDEs, younger age at onset of depression, treatment-seeking for depression, female sex, being White, having a lower household income and having been exposed to a greater number of stressful life events within the past year (Table 1). Recurrence of MDE was significantly associated with all comorbid mental disorders (except for dysthymia, alcohol and drug use disorders and dependent and antisocial personality disorders), lower levels on the mental component summary score, several symptoms of MDE (including anhedonia, increase of appetite, hypersomnia, psychomotor retardation and agitation, feeling of worthlessness, diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness and recurrent thoughts of death), greater number of lifetime MDEs, family history of depression, younger age at onset of depression, treatment-seeking for depression, female sex and younger age.

Structure of comorbid mental disorders and symptoms of MDE

The bifactor model of the three dimensions of psychopathology provided a good fit for the data (CFI=0.964, TLI=0.952, RMSEA=0.020) and the CFA model of the 14 DSM-IV symptoms of MDE (CFI=0.941, TLI=0.922, RMSEA=0.044) provided adequate fit for the data (eTables 1 and 2).

Predictive structural equation model of the 3-year risk of MDE persistence and recurrence

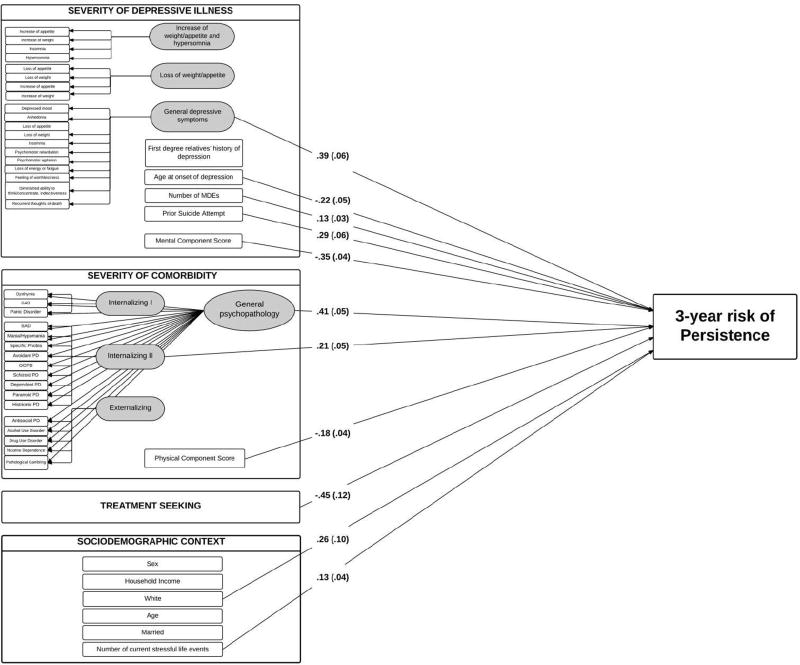

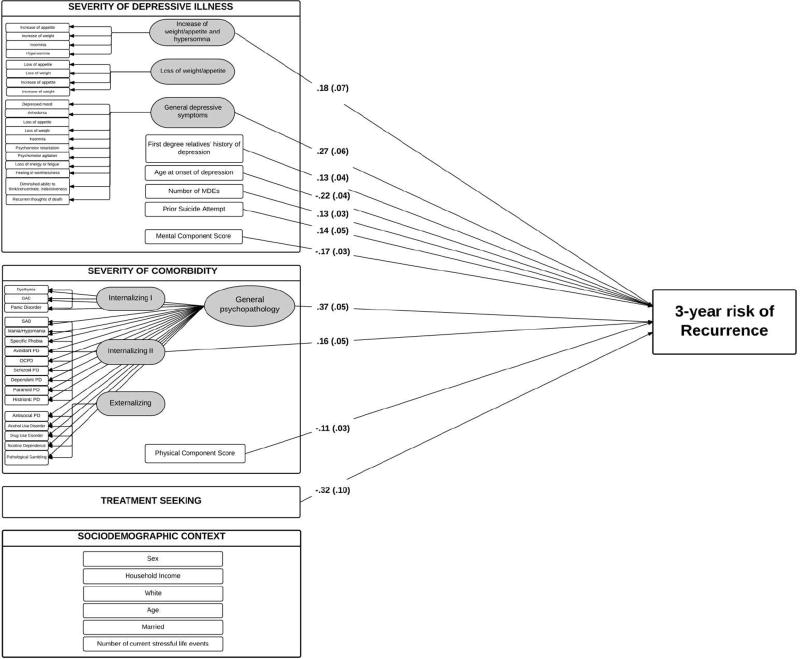

After adjustments for all other factors, several factors significantly increased the risk of MDE persistence and recurrence (Figures 2 and 3). These included the general depressive symptom dimension representing the shared effects across most depressive symptoms, the general psychopathology factor representing the shared effect across all comorbid mental disorders, the internalizing II factor, lower mental and physical component summary scores, younger age at onset of major depression, greater number of lifetime MDEs and prior suicide attempts. Treatment-seeking behavior had a significant protective effect against the risk of MDE persistence and recurrence (Figure 2). In addition, family history of depression and the factor “increase of weight/appetite and hypersomnia” were associated with MDE recurrence, while the risk of MDE persistence was significantly associated with the number of stressful life events and being White. The R-squares of models of MDE persistence and recurrence were 0.71 and 0.43, indicating that the model explained respectively 71% of the 3-year risk of persistence and 43% of the risk of recurrence of MDE associated with the predictors assessed at baseline.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of the 3-year risk of MDE persistence in a general population sample of adults with a major depressive episode (n = 2,587).

Ellipses are used to denote latent constructs, rectangles are used to denote the observed variables measuring or impacting on these constructs.

The two bifactor models parse respectively disorder and symptoms of MDE variances into general variance (i.e., variance of the general psychopathology factor for comorbid mental disorders and variance of the general depressive liability for symptoms of MDE), variance of specific dimensions (e.g., variance of the internalizing I, internalizing II and externalizing dimensions for comorbid mental disorders and variance of sleep disturbance, weight/appetite disturbance and general depressive symptoms dimensions for symptoms of MDE), and unique variance (variance of each mental disorder per se and variance of each symptom of MDE per se).

Arrows indicate significant associations (two-sided p < .01). There is no other latent factor or disorder or symptom of MDE with modification index greater or equal to 10 to predict persistence in addition.

Regression coefficients shown are standardized. Values in brackets indicate their standard errors.

Axis I disorders were past year diagnoses while Axis II disorders were assessed on a lifetime basis.

Abbreviations: MDE, major depressive episode; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; OCPD, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder; PD, personality disorder.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model of the 3-year risk of MDE recurrence in a general population sample of adults with a major depressive episode (n = 2,587).

Ellipses are used to denote latent constructs, rectangles are used to denote the observed variables measuring or impacting on these constructs.

The two bifactor models parse respectively disorder and symptoms of MDE variances into general variance (i.e., variance of the general psychopathology factor for comorbid mental disorders and variance of the general depressive liability for symptoms of MDE), variance of specific dimensions (e.g., variance of the internalizing I, internalizing II and externalizing dimensions for comorbid mental disorders and variance of sleep disturbance, weight/appetite disturbance and general depressive symptoms dimensions for symptoms of MDE), and unique variance (variance of each mental disorder per se and variance of each symptom of MDE per se).

Arrows indicate significant associations (two-sided p < .01). There is no other latent factor or disorder or symptom of MDE with modification index greater or equal to 10 to predict recurrence in addition.

Regression coefficients shown are standardized. Values in brackets indicate their standard errors.

Axis I disorders were past year diagnoses while Axis II disorders were assessed on a lifetime basis.

Abbreviations: MDE, major depressive episode; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; OCPD, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder; PD, personality disorder.

Discussion

In a large, nationally representative cohort of US adults, we sought to build a comprehensive model of MDE persistence and recurrence that integrates information across a wide range of clinical domains to estimate their relative impact. About 36% of individuals with an MDE at Wave 1 had either a persistent or a recurrent MDE at 3-year follow-up. Risk of persistence or recurrence of MDE was not determined by a single factor, but rather by the combined effects of multiple risk factors. Most predictors were common to both persistence and recurrence and included the severity of the depressive illness, the severity of mental and physical comorbidities, older age and a failure to seek treatment for MDE at Wave 1. The model predicted 71% of the variance of MDE persistence and 43% of the variance of MDE recurrence. Several novel findings emerged from this model.

The two strongest predictors of persistence and recurrence in individuals with MDE were severity of depression and severity of comorbidity. Our results extend previous findings (Grilo et al., 2005; Keller et al., 1982, 1992; Klein, Shankman, 2006; Sargeant et al., 1990; Skodol et al., 2011, 2011b; Spijker et al., 2010; Steinert et al., 2014) by showing that the effect of comorbidity or depression itself on the risk of persistence or recurrence of MDE is not uniquely related to one specific mental disorder or depression symptom, but rather related to the number and severity of mental disorders and depressive symptoms. Because effects of comorbid psychiatric disorders remained strong after taking into account treatment of MDE, our results highlight the need to develop interventions that can simultaneously target multiple psychiatric disorders to decrease the risk of MDE persistence and recurrence (Blanco et al., 2017; Bullis et al., 2014; Roy-Byrne et al., 2010; Sullivan et al., 2007). At a more general level, our findings that dimensions of psychopathology may predict MDE course are consistent with current dimensional conceptualizations of psychopathology (Blanco et al., 2013; Eaton et al., 2012; Hoertel et al., 2015a, 2015b; Kim and Eaton, 2015; Kotov et al., 2011; Krueger et al., 1998; Krueger and Markon, 2006) and call for identification of psychological and biological mechanisms underlying these broad psychopathological dimensions.

The internalizing II factor increased independently the risk of MDE persistence and recurrence in our model. This factor was mainly positively measured by social anxiety disorder and avoidant personality disorder and mainly negatively measured by histrionic personality disorder (eTable 2). Prior research suggests that genetic and environmental risk factors for social anxiety disorder and avoidant personality disorder are shared to a large degree (Isomura et al., 2015; Torvik et al., 2016). It is plausible that both disorders reflect temperamental traits such as behavioral inhibition and fear of social situations (Torvik et al., 2016), which are rarely observed in individuals with histrionic personality disorder who classically present high levels of extraversion (Furnham, 2014), and has been shown to predict worse MDE course (Kasch et al., 2002).

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to show in a nationally representative sample that seeking treatment for MDE decreases the risk of persistence and recurrence in individuals with MDE. Individuals seeking treatment for MDE tend to have relatively high rates of comorbidity and depression severity (Blumenthal and Endicott, 1996; Cohen and Cohen, 1984; Hoertel et al., 2013d, 2014; Kendler, 1995). In our study, only half of the participants who had a persistent or a recurrent MDE sought help for depression at Wave 1. Strategies that seek to promote mental health care seeking for individuals with an MDE, such as large-scale anti-stigma campaigns (Henderson et al., 2013), could help decrease rates of MDE persistence and recurrence. Lifetime history of suicide attempts also predicted these risks, consistent with findings from a prior study (Jang et al., 2013). Assessing suicide risk (Oquendo et al., 2004, 2006) could have the additional benefit of helping to predict the course of MDE.

Sex, age, household income, and marital status did not independently predict the risk of persistence or recurrence of MDE in our model. These results suggest that these sociodemographic variables, which are often non-modifiable factors, may increase the risk of MDE persistence or recurrence mostly through the increase of severity of depression and comorbidity rather than directly.

This study has several limitations. First, despite its prospective design, our study cannot definitely establish a causal relationship between the identified risk factors and recurrence and persistence (Le Strat and Hoertel, 2011). Second, NESARC relied on self-report, which is susceptible to reporting and recall biases. Third, our study examined the course of MDE over a three-year period; the pattern of associations may differ for longer periods of time. Fourth, the survey data did not permit assessment of the length of depressive episodes at baseline. Fifth, we adopted specific conventions to approximate recurrence and persistence. Other conventions might have yielded different results. Sixth, although borderline, narcissistic and schizotypal personality disorders were assessed in Wave 2, we decided not to include them in our study to preserve its prospective design. However, the structure of psychiatric disorders seems to be robust to the inclusion of a broad range of disorders and the inclusion of these personality disorders in supplementary analyses did not modify the significance of our results (data not shown). Last, our results require confirmation in other samples before they can be generalized to other populations, such as those living outside the United States.

In conclusion, this population-based model of risk for MDE persistence or recurrence identified several predictors from multiple domains. Clinicians assessing risk of persistence or recurrence in adults with MDE should carefully evaluate the severity of depression and the number and severity of Axis I and Axis II comorbid disorders, and inquire about past suicide attempts, quality of life, age at onset of depression, number of lifetime MDEs, family history of depression and stressful life events. Reducing the risk of unfavorable course of MDE is one of the essential goals of maintenance treatment. We hope that this model helps clinicians to evaluate this risk and to develop clinical and public health interventions to decrease the burden of this common disorder.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We developed a comprehensive model of the 3-year risk of MDE persistence and recurrence. We used structural equation modeling in a nationally representative sample.

Main independent predictive factors at baseline were:

-

-

severity of the depressive illness,

-

-

severity of psychiatric and other physical comorbidities,

-

-

quality of life,

-

-

failure to seek treatment for MDE.

This model highlights strategies that may improve the course of MDE.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Blanco holds stock in Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Inc and General Electric. Dr. Oquendo receives royalties for the commercial use of the C-SSRS and her family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Falissard has been consultant for E. Lilly, BMS, Servier, SANOFI, GSK, HRA, Roche, Boeringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Almirall, Allergan, Stallergene, Genzyme, Pierre Fabre, Astrazeneca, Novartis, Janssen, Astellas, Biotronik, Daiichi-Sankyo, Gilead, MSD, Lundbeck, Stallergene, Actelion, UCB, Otsuka, Grunenthal and ViiV. Dr. Lemogne reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Lundbeck, personal fees from Servier, Daiichi-Sankyo and Janssen, and non-financial support from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work.

Funding/support: This study was supported by NIH grants MH076051 and MH082773 (Drs. Blanco, Olfson, Oquendo and Wall) and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Drs. Hoertel, Blanco, Olfson, Oquendo and Wall) and a fellowship grant from Public Health Expertise (Dr. Hoertel). The sponsors had no additional role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Role of the Funding Source: The funding sources had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Additional information: The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions was sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and funded, in part, by the Intramural Program, NIAAA, National Institutes of Health. The original data set for the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is available from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (http://www.niaaa.nih.gov).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: Other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: NH, CB and FL designed the study. NH and MW undertook statistical analyses. NH and CB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MAO, MW, MO, BF, SF, HP, CL, and FL reviewed the draft. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the US government.

References

- Avery D, Winokur G. Suicide, attempted suicide, and relapse rates in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:749–53. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300091010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Krueger RF, Hasin DS, Liu SM, Wang S, Kerridge BT, et al. Mapping common psychiatric disorders: structure and predictive validity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA psychiatry. 2013;70:199–208. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Vesga-Lopez O, Stewart JW, Liu SM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of major depression with atypical features: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:224–32. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Wall MM, Wang S, Olfson M. Examining heterotypic continuity of psychopathology: a prospective national study. Psychol Med. 2017;12:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S003329171700054X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal R, Endicott J. Barriers to seeking treatment for major depression. Depress Anxiety. 1996;4:273–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:6<273::AID-DA3>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Stretch DD, MacCarthy B, Wykes T. Predicting the short-term outcome of first episodes and recurrences of clinical depression: a prospective study of life events, difficulties, and social support networks. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:298–306. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullis JR, Fortune MR, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. A preliminary investigation of the long-term outcome of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(8):1920–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M, Ramírez R, Febo VE, Rubio-Stipec M, Fernández RL, et al. The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 1999;60:790–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji S, Saunders JB, Vrasti R, Grant BF, Hasin D, Mager D. Reliability of the alcohol and drug modules of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule--Alcohol/Drug-Revised (AUDADIS-ADR): an international comparison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:171–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J. The clinician’s illusion. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:1178–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230064010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman I, Naicker K, Zeng Y, Ataullahjan A, Senthilselvan A, Patten SB. Predictors of long-term prognosis of depression. CMAJ. 2011;183:1969–76. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowrick C, Shiels C, Page H, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Casey P, Dalgard OS, et al. Predicting long-term recovery from depression in community settings in Western Europe: evidence from ODIN. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:119–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Balsis S, Skodol AE, Markon KE, et al. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: Evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:282–8. doi: 10.1037/a0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandiño-Losada A, Bangdiwala SI, Lavebratt C, Forsell Y. Path analysis of the chronicity of depression using the comprehensive developmental model framework. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;29:1–12. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2015.1134651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C, Belaise C. The concept of recovery in major depression. Psychol Med. 2007;37:307–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, et al. Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:1093–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810240013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A. A bright side, facet analysis of histrionic personality disorder: the relationship between the HDS Colourful factor and the NEO-PI-R facets in a large adult sample. J Soc Psychol. 2014;154:527–36. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2014.953026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Trinh NH, Smoller JW, Fava M, Murphy JM, Breslau J. Psychosocial stressors and the prognosis of major depression: a test of Axis IV. Psychol Med. 2013;43:303–16. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–66. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Gunderson JG, et al. Two-year prospective naturalistic study of remission from major depressive disorder as a function of personality disorder comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:78–85. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, Hendriks SM, Licht CM, Nolen WA, et al. Recurrence of major depressive disorder across different treatment settings: results from the NESDA study. J Affect Disord. 2013a;147:225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, Nolen WA, Beekman AT. Recurrence of major depressive disorder and its predictors in the general population: results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS) Psychol Med. 2013b;43:39–48. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:133–41. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman GA, Ogburn E, Gorroochurn P, Keyes KM, Hasin D. Evidence for a two-stage model of dependence using the NESARC and its implications for genetic association studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:258–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:777–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Franco S, Wall MM, Oquendo MA, Kerridge BT, Limosin F, et al. Mental disorders and risk of suicide attempt: a national prospective study. Mol Psychiatry. 2015a;20:718–26. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Le Strat Y, Angst J, Dubertret C. Subthreshold bipolar disorder in a U.S. national representative sample: prevalence, correlates and perspectives for psychiatric nosography. J Affect Disord. 2013a;146:338–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Le Strat Y, Gorwood P, Bera-Potelle C, Schuster JP, Manetti A, et al. Why does the lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder in the elderly appear to be lower than in younger adults? Results from a national representative sample. J Affect Disord. 2013b;149:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Le Strat Y, Lavaud P, Dubertret C, Limosin F. Generalizability of clinical trial results for bipolar disorder to community samples: findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013c;74:265–70. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Le Strat Y, Limosin F, Dubertret C, Gorwood P. Prevalence of subthreshold hypomania and impact on internal validity of RCTs for major depressive disorder: results from a national epidemiological sample. PloS One. 2013d;8:e55448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Limosin F, Leleu H. Poor longitudinal continuity of care is associated with an increased mortality rate among patients with mental disorders: Results from the French National Health Insurance Reimbursement Database. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(6):358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, McMahon K, Olfson M, Wall MM, Rodriguez-Fernandez JM, Lemogne C, et al. A dimensional liability model of age differences in mental disorder prevalence: Evidence from a national sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2015b;64:107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Amsterdam JD, Salomon RM, O’Reardon JP, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:417–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Isomura K, Boman M, Rück C, Serlachius E, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, et al. Population-based, multi-generational family clustering study of social anxiety disorder and avoidant personality disorder. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1581–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S, Jung S, Pae C, Kimberly BP, Craig Nelson J, Patkar AA. Predictors of relapse in patients with major depressive disorder in a 52-week, fixed dose, double blind, randomized trial of selegiline transdermal system (STS) J Affect Disord. 2013;151:854–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002 Nov;111(4):589–97. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Lewis CE, Klerman GL. Predictors of relapse in major depressive disorder. JAMA. 1983;250:3299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Coryell W, Hirschfeld RM, et al. Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression. A 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:809–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100053010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Shapiro RW, Lavori PW, Wolfe N. Recovery in major depressive disorder: analysis with the life table and regression models. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:905–10. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Is seeking treatment for depression predicted by a history of depression in relatives? Implications for family studies of affective disorder. Psychol Med. 1995;25:807–14. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Eaton NR. The hierarchical structure of common mental disorders: Connecting multiple levels of comorbidity, bifactor models, and predictive validity. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015 Nov;124(4):1064–78. doi: 10.1037/abn0000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Schatzberg AF, McCullough JP, Dowling F, Goodman D, Howland RH, et al. Age of onset in chronic major depression: relation to demographic and clinical variables, family history, and treatment response. J Affect Disord. 1999;55:149–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Shankman SA, Rose S. Ten-year prospective follow-up study of the naturalistic course of dysthymic disorder and double depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:872–80. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Yonkers KA, McCullough JP, Keitner GI, et al. Gender differences in chronic major and double depression. J Affect Disord. 2000;60:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Ruggero CJ, Krueger RF, Watson D, Yuan Q, Zimmerman M. New dimensions in the quantitative classification of mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1003–11. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): a longitudinal-epidemiological study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:216–27. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: a model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:111–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, McIntyre RS, Milev R, Ramasubbu R, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III. Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2009;(117 Suppl 1):S26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Strat Y, Hoertel N. Correlation is no causation: gymnasium proliferation and the risk of obesity. Addiction. 2011;106:1871–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Aggen S, Shi S, Gao J, Li Y, Tao M, et al. The structure of the symptoms of major depression: exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in depressed Han Chinese women. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1391–401. doi: 10.1017/S003329171300192X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson JF, Blashill AJ, Wall MM, Balan IC, Wang S, Lejuez CW, et al. Relationship between psychiatric disorders and sexually transmitted diseases in a nationally representative sample. J Psychosom Res. 2014 Apr;76(4):322–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetti A, Hoertel N, Le Strat Y, Schuster JP, Lemogne C, Limosin F. Comorbidity of Late-Life Depression in the United States: A Population-based Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(11):1292–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, et al. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1000–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide Los Angeles. :1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Currier D, Mann JJ. Prospective studies of suicidal behavior in major depressive and bipolar disorders: what is the evidence for predictive risk factors? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:151–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, et al. Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1433–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Wang JL, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Khaled SM, Bulloch AG. Predictors of the longitudinal course of major depression in a Canadian population sample. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:669–76. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Bulloch AG, MacQueen G. Depressive episode characteristics and subsequent recurrence risk. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:277–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Rose RD, Edlund MJ, Lang AJ, et al. Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care. JAMA. 2010;303:1921–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio JM, Olfson M, Perez-Fuentes G, Garcia-Toro M, Wang S, Blanco C. Effect of first episode axis I disorders on quality of life. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:271–4. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio JM, Olfson M, Villegas L, Perez-Fuentes G, Wang S, Blanco C. Quality of life following remission of mental disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:E445–50. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant JK, Bruce ML, Florio LP, Weissman MM. Factors associated with 1-year outcome of major depression in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:519–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Grilo CM, Keyes K, Geier T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Relationship of personality disorders to the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally representative sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:257–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Shea MT, Warshaw M, et al. Recovery from major depression. A 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1001–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijker J, de Graaf R, Ten Have M, Nolen WA, Speckens A. Predictors of suicidality in depressive spectrum disorders in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:513–21. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert C, Hofmann M, Kruse J, Leichsenring F. The prospective long-term course of adult depression in general practice and the community. A systematic literature review. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan G, Craske MG, Sherbourne C, Edlund MJ, Rose RD, Golinelli D, et al. Design of the Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM) study: innovations in collaborative care for anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Doesschate MC, Bockting CL, Koeter MW, Schene AH, Group DS. Prediction of recurrence in recurrent depression: a 5.5-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:984–91. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04858blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik FA, Welander-Vatn A, Ystrom E, Knudsen GP, Czajkowski N, Kendler KS, et al. Longitudinal associations between social anxiety disorder and avoidant personality disorder: A twin study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125:114–24. doi: 10.1037/abn0000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Patten S, Sareen J, Bolton J, Schmitz N, MacQueen G. Development and validation of a prediction algorithm for use by health professionals in prediction of recurrence of major depression. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:451–7. doi: 10.1002/da.22215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Patten SB, Currie S, Sareen J, Schmitz N. Predictors of 1-year outcomes of major depressive disorder among individuals with a lifetime diagnosis: a population-based study. Psychol Med. 2012;42:327–34. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.