Abstract

Teen dating violence (TDV) is a serious and prevalent public health problem. TDV is associated with a number of negative health consequences for victims and predicts violence in adult relationships. Thus, efforts should be devoted to the primary prevention of TDV. However, only a few studies have examined when the risk for the first occurrence of TDV is greatest. Continued research in this area would inform the timing of, as well as developmentally appropriate strategies for, TDV primary prevention efforts. The current study examined at which age(s) the risk for TDV perpetration onset was greatest. Utilizing a panel-based design, a sample of racially/ethnically diverse high school students (N = 872; 56% female) from the Southwestern United States completed self-report surveys on physical and sexual TDV perpetration annually for six years (2010 to 2016). Findings suggested that the physical TDV risk of onset was at or before ages 15 to 16 for females and at or before age 18 for males. For sexual TDV perpetration, risk was similar for males and females during adolescence, before uniquely increasing for males, and not females in emerging adulthood. Findings highlight the need for TDV primary prevention programs to be implemented early in high school, and potentially in middle school.

Keywords: Teen dating violence, prevention, adolescence, survival analysis

Teen dating violence (TDV) is a prevalent and serious public health problem. Each year as many as 20% of adolescents are victimized by or perpetrate physical TDV and 10–20% are victimized by or perpetrate sexual TDV (Choi & Temple, 2016; Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008). With the exception of sexual TDV, which is more frequently perpetrated by males, the prevalence of TDV is similar for both genders (Shorey et al., 2008). In addition, victims of TDV, relative to non-victims, evidence a number of negative outcomes, including depressive and posttraumatic stress symptomatology (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008), alcohol and drug use (Parker, Debnam, Pas, & Bradshaw, 2016), sexually transmitted infections and risky sexual behavior (Silverman, Raj, Mucci, & Hathaway, 2001; Shorey et al., 2015), and suicidal ideation (Nahapetyan, Orpinas, Song, & Holland, 2014). Thus, it is imperative that effective primary prevention programs for TDV perpetration be implemented.

A number of TDV prevention programs are being implemented and have been empirically examined with adolescents (e.g., De La Rue et al., 2017; O’Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009). However, research on when (i.e., at what age) primary prevention programs for TDV perpetration should be implemented is scarce. The lack of research remains despite calls from researchers to implement primary prevention programs for TDV perpetration (e.g., Foshee & Reyes, 2009; Whitaker et al., 2006), as interventions for reducing violence, once violence has been established in a relationship, are minimally effective (De La Rue et al., 2017; Shorey et al., 2012). Adolescence represents a sensitive time for the development of TDV perpetration (Johnson, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2015), with middle adolescence and emerging adulthood (i.e., ages 15–25) representing the period when risk for intimate partner violence (IPV) is greatest (Johnson et al., 2015; O’Leary & Smith Slep, 2003). Identifying the time periods of greatest risk for the emergence of these violent behaviors is critical for effective primary prevention programming due to the remarkable stability of TDV perpetration throughout adolescence and during the transition into adulthood (Johnson et al., 2015; O’Leary & Smith Slep, 2003).

To date, few studies have examined at what age(s) the risk for the onset of TDV perpetration is greatest. Bonomi and colleagues (2012), in a sample of college students utilizing retrospective self-report, demonstrated that, for females, the first instance of physical TDV victimization occurred between the ages of 16–17 for 66.7% of victims and the first instance of sexual TDV victimization occurred between the ages of 16–17 for 62.5% of victims. For males, the first instance of physical TDV victimization occurred between the ages of 16–17 for 44.5% of victims and the first instance of sexual TDV victimization occurred between the ages of 16–17 for 41.7% of victims. Johnson and colleagues (2015) also demonstrated that between the ages of 13–16, approximately 13% of males and 20% of females had perpetrated physical TDV, with these rates increasingly slightly (i.e., 19% and 23% for males and females, respectively) from ages 17–20. Thus, mid-adolescence appears to be a particularly risky time period for the onset of TDV, although there is a lack of research that has prospectively examined at which age(s) the risk for onset of TDV perpetration is greatest.

The importance of determining the age of onset of TDV perpetration is amplified when considering recommendations for effective primary prevention programs. Specifically, the implementation of prevention programs need to be appropriately timed in order to maximize effectiveness (Nation et al., 2003). That is, many primary prevention programs are implemented after adolescents are already exhibiting the behavior(s) that the programs are intended to prevent (Nation et al., 2003). Indeed, most TDV perpetration prevention programs include adolescents who have already perpetrated (e.g., Foshee et al., 1998; Wolfe et al., 2003). Moreover, providing primary prevention programming too early may also limit effectiveness. As stated by Mrazek and Haggerty (1994), “…if the preventive intervention occurs too early, its positive effects may be washed out before onset; if it occurs too late, the disorder may have already had its onset” (p. 14). Thus, continued empirical research is needed on what age(s) the risk for the onset of different forms of TDV perpetration is greatest, which will have direct implications for the timing of TDV perpetration primary prevention efforts.

Additionally, continued research is needed that examines whether age of onset of TDV perpetration varies by gender and race/ethnicity. Although research often shows similar prevalence rates of physical TDV perpetration for males and females, men more frequently perpetrate sexual TDV (Shorey et al., 2008). Some research suggests African American adolescents may have a higher prevalence of TDV perpetration than Hispanic and Caucasian adolescents, and Hispanic adolescents may have a higher prevalence than Caucasian adolescents (e.g., Chapple, 2003; Foshee et al., 2010). Thus, due to the differences in the prevalence of TDV perpetration across gender and race/ethnicity, it is possible that onset may also vary across these demographic factors. Knowledge of whether onset varies across these factors will provide important information on whether primary prevention programs for TDV perpetration can be universally administered across genders and racial/ethnic groups, or whether programs will need to be tailored toward specific subgroups of adolescents.

Thus, the present study examined when onset for physical and sexual TDV perpetration was greatest from the ages of 14 to 20 utilizing a prospective design in a large, racially/ethnically diverse sample of adolescents. Examining the age of onset of TDV perpetration will inform researchers and practitioners on the time period(s) when primary prevention programs for TDV perpetration should be implemented. We also examined whether risk for onset of TDV perpetration varied across males and females, as well as race/ethnicity. Based on prior research, we hypothesized that the age of onset for physical and sexual TDV would be greatest in middle-to-late adolescence. We made no a priori hypotheses regarding whether risk of onset would vary across gender or race/ethnicity due to limited research in this area.

Method

Participants

We used a subsample of participants from an ongoing longitudinal study of adolescent health (Temple et al., 2013). Participants included 872 freshmen and sophomore high school students recruited from seven public schools in southeast Texas. For this particular study, data are from Waves 1–6. Retention rates across the 6 year study ranged from 67% (Wave 5) to 92.5% (Wave 2).1 At Wave 1, the sample had a mean age of 15.09 (SD=0.77), consisted of slightly more females (56%) than males, and self-identified as Hispanic (31.5%), White (29.7%), African American (28%), and other (e.g., Asian American; 10.8%). Additional, 92% reported that they had begun dating at Wave 1.

Procedures

Participants received a $10 gift card at Waves 1–3, a $20 gift card at Waves 4–5, and a $30 gift card at Wave 6. Teachers and other school administrators were not allowed to be present during questionnaire administration, which occurred during normal school hours in a private classroom. When participants graduated high school, administration moved from paper-pencil to web-based surveys and the presentation of the surveys were identical across formats. The study was approved by the last author’s Institutional Review Board and active parent consent and student assent/consent were obtained. Detailed information on study procedures have been published previously (Temple et al., 2013).

Measures

Demographics

At the first assessment, participants completed a demographic questionnaire to indicate their age, gender, race/ethnicity, dating history, and year in high school.

TDV

Perpetration of physical and sexual TDV was measured using the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI; Wolfe et al., 2001). Adolescents responded Yes/No to questions about their own behavior in their lifetime (Baseline) and in the past year (Waves 2–6). Four items assessed physical TDV perpetration (e.g., “I kicked, hit, or punched him/her”) and 4 items assessed sexual TDV perpetration (e.g., “I forced him/her to have sex when he/she didn’t want to”). For the current study, we considered endorsement of at least one physical item and one sexual item to represent TDV perpetration for each type of violence, respectively, consistent with prior research (Bell & Naugle, 2007; Shorey et al., 2011). The CADRI has demonstrated good psychometric properties in adolescent populations (Wolfe et al., 2001).

Data Analytic Plan

To determine the age of onset for TDV perpetration we followed a survival analytic plan (Singer & Willett, 2003). All analyses were conducted on a sample of adolescents who reported not previously perpetrating physical or sexual TDV at baseline to ensure we were assessing age of onset for TDV perpetration. Preliminary binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine if age of entry into the study or higher ordered interactions between race and sex influenced TDV perpetration. If the interactions between race and sex were non-significant, they were entered into subsequent survival analyses as independent predictors. Logit hazard ratios were initially examined to see if the pattern of data varied over time and required demographic variables to be entered as time-varying covariates. Specifically, in these situations we created an interaction term between the covariate (i.e., gender or race) and time. If the pattern of findings remained similar, sex and/or race was entered as a time-invariant covariate.

We next examined whether onset for each type of TDV was best described as a constant, linear, quadratic or cubic pattern of time. Support for a constant model suggests that risk for onset does not vary across the study period. A linear trend suggests that perpetration onset follows a continuous path throughout adolescence (i.e., either increases or decreases). A quadratic trend suggests a significant peak (negative coefficient) or trough (positive coefficient) for perpetration onset, followed by a return rate similar to that seen at baseline. Finally, a cubic trend suggests a significant peak and trough. If negative, the pattern suggests an early trough and late peak, while a positive coefficient represents an early peak followed by a later trough. Once the best time pattern for each outcome was established, we investigated whether gender or race predicted a differing time to event rate across our perpetration outcomes in Cox regression survival models. Cumulative and median survival times were calculated as indices for rate of change within our models and hazard functions across the range of our study were presented in figures. All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 23.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

At Wave 1, 22% (n=188) of participants reported perpetrating physical TDV and 11% (n=100) reported previously perpetrating sexual TDV. These adolescents were eliminated from the study and we subsequently conducted our analyses on 684 and 772 adolescents with regard to physical and sexual TDV perpetration, respectively. Adolescents who reported perpetrating physical TDV at Wave 1 were disproportionately female (X2(1)=24.61, p<.01), while African American adolescents were overrepresented and White youth were underrepresented among prior perpetrators (X2(1)=24.61, p<.01). Findings did not vary as a function of gender or race for sexual TDV perpetration at Wave 1 (ps>.40). Preliminary analyses suggested that age of entry into the study was a non-significant predictor for physical (p=.50) and sexual (p=.36) TDV perpetration, and that the interaction between age and sex was non-significant for both forms of TDV perpetration (p>.20). Thus, age of entry was not used as a covariate in our analyses and gender and age were investigated independently. Table 1 displays means and standard deviations of TDV perpetration across ages.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and range of scores for TDV perpetration; 2010–2016 in southeast Texas.

| Age | Physical TDV Perpetration M (SD); Range |

Sexual TDV Perpetration M (SD); Range |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | .32 (.84); 0–4 | .10 (.33); 0–2 |

| 15 | .37 (.90); 0–4 | .12 (.34); 0–2 |

| 16 | .37 (.87); 0–4 | .12 (.38); 0–3 |

| 17 | .42 (1.00); 0–4 | .12 (.38); 0–3 |

| 18 | .31 (.85); 0–4 | .12 (.42); 0–4 |

| 19 | .33 (.83); 0–4 | .14 (.45); 0–4 |

| 20 | .42 (1.00); 0–4 | .15 (.47); 0–3 |

Note: TDV = Teen dating violence.

Survival Analyses

For sexual TDV perpetration, patterns of logit hazard ratios were similar across race/ethnicity, but descriptively varied over time for males and females (e.g., at age 17, rates increased for males but remained stable for females). In contrast, the proportional hazard assumption was intact with regard to gender for physical TDV perpetration, but potentially violated when examining physical perpetration across race/ethnicity (e.g., at age 18 rates of perpetration increased drastically in African Americans, slightly increased in Whites, and decreased in Hispanic adolescents). Thus, race was time invariant when predicting sexual TDV perpetration and time variant while predicting physical TDV perpetration, while gender was time-invariant when predicting physical TDV perpetration and time-variant when predicting sexual TDV perpetration. The best fitting time pattern was next established for physical and sexual TDV perpetration. For sexual TDV perpetration, a quadratic model was significant (B=−.54; SE=.25; Wald=4.56; p=.03) suggesting a sensitive period earlier in development before baseline levels returned. For physical TDV perpetration, we identified a cubic model as the best fitting model (B=.05; SE=.016; Wald=8.56; p=.003), suggesting that physical TDV perpetration increased early and then decreased below baseline rates towards the end of the study.

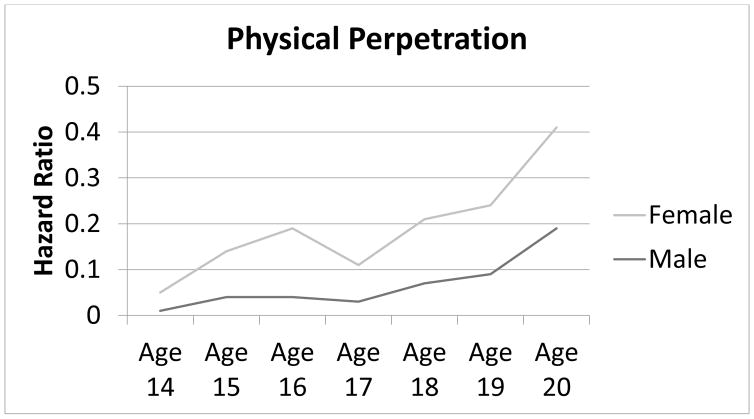

Finally, we tested whether TDV perpetration onset varied as a function of gender or race. With regard to physical TDV perpetration, we found that females (B=−.92; SE=.16; Wald=34.57; p<.001) experienced a faster time of onset compared to males. Annual hazard functions for both males and females are modeled separately in Figure 1. In females, the pattern suggested a peak in middle adolescence, and an increasing pattern in late adolescence. Meanwhile, for males the pattern suggested a relatively consistent pattern during middle adolescence with a slight increase in late-adolescence (i.e., ages 18–20). As neither males nor females reached a median survival time of 50%, we set our median survival time at 10%.2 Findings suggested that females achieved this median survival time between the ages of 15 and 16, while 10% of males did not report an onset of physical TDV perpetration until the age of 18. By the end of the study, slightly more females (20%) reported physical TDV perpetration compared to males (17%). As for race/ethnicity, findings suggested that the pattern of findings concerning time of onset were not significantly different (p>.10).

Figure 1.

Hazard ratios for age of onset of physical TDV perpetration; 2010–2016 in southeast Texas.

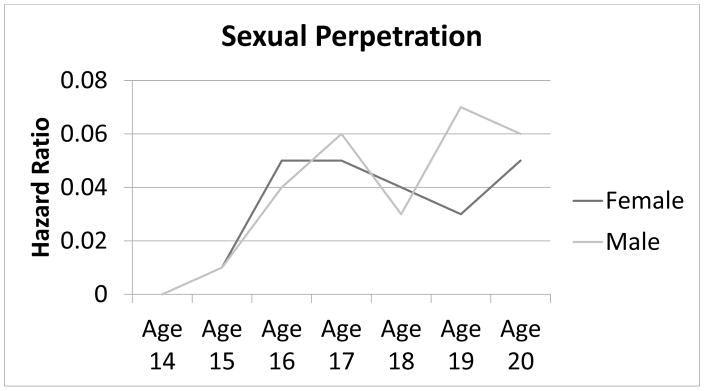

As for sexual TDV perpetration, findings suggested that males experienced faster onset compared to females (B=.03; SE=.01; Wald=11.57; p=.001). Hazard functions are modeled separately in Figure 2. Findings suggested a similar pattern of risk for males and females between the ages of 14 and 18. However, differences between males and females emerged after the age of 18, where male perpetration risk increased, even compared to previous male levels, while female rates remained lower. This pattern can be seen explicitly when investigating cumulative survival times. Through age 18, exactly 10% of males and females had sexually perpetrated; however, after age 18, an additional 25% of men perpetrated (35% total) while only an additional 14% of women perpetrated (24% total). With regard to race, no significant differences emerged (p>.10).3

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios for age of onset of sexual TDV perpetration; 2010–2016 in southeast Texas.

Discussion

Efforts to implement effective TDV primary prevention programs have been hindered by minimal research on when the risk for TDV perpetration onset begins. In the current study, we examined at what age(s) risk for physical and sexual TDV perpetration onset were greatest, and whether this varied by gender and race/ethnicity. This information will help inform researchers and clinicians on when primary prevention programs for TDV perpetration should be implemented.

Regarding risk of onset for physical TDV perpetration, findings suggested slightly different patterns for females and males. Specifically, risk for females showed a peak in middle adolescence (i.e., ages 15–16), and an increasing pattern in late adolescence. In contrast, for males findings suggested a relatively consistent pattern during middle adolescence with a slight increase in late-adolescence (i.e., ages 18–20). These findings are consistent with prior research which suggests the risk for physical violence between partners begins to peak in middle-to-late adolescence and young adulthood (Johnson et al., 2015) and is also consistent with the limited research to date which has examined when risk for the onset of physical TDV is greatest (Bonomi et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2015). Additional research is needed, however, to understand why females have a slightly earlier age of onset of physical TDV than their male counterparts. Because female-perpetrated violence is perceived as more acceptable among adolescents than male-perpetrated violence (Sears et al., 2006; Temple et al., 2013), it is plausible that these beliefs contribute to the earlier age of onset for female physical TDV perpetration. However, future research is needed that examines the psychosocial risk factors (e.g., emotion regulation difficulties, beliefs about violence, substance use) that predict the onset of TDV perpetration, as prevention programs could then develop intervention components that aim to modify these risk factors.

An interesting pattern of findings emerged for sexual TDV perpetration. Specifically, findings suggested a similar pattern of risk for males and females between the ages of 14 and 18. However, differences between males and females emerged after the age of 18, where male perpetration risk increased, even compared to their previous levels, while female rates remained lower. These findings are consistent with prior research that has shown men perpetrate sexual TDV more frequently than women (Shorey et al., 2008), and also suggest that men’s risk for sexual perpetration is greatest in late-adolescence. Specifically, after age 18, risk for sexual TDV risk was markedly higher for men. Prior research has shown sexual behavior increases dramatically from early-to-late adolescence (Liu et al., 2015), and our findings suggest there is a corresponding increase in sexual TDV from early-to-late adolescence as more adolescents become sexually active. These results highlight the importance of primary prevention programs for men’s sexual violence in early-to-late adolescence.

Our results also demonstrated no significant differences between racial/ethnic groups on the age of onset for physical or sexual TDV perpetration. These findings stand in contrast to research which suggests that the frequency of TDV perpetration may differ across racial/ethnic groups (Chapple, 2003; Foshee et al., 2010). This suggests that risk for TDV perpetration begins to differ among racial/ethnic groups after initial onset of perpetration and also indicates that primary prevention programming for TDV perpetration can occur at the same age for adolescents of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. Future research is needed, however, to examine whether risk factors for the onset of TDV perpetration is invariant among racial/ethnic groups.

These findings, along with that of previous research (e.g., Johnson et al., 2015), provide information that may be important for TDV primary prevention programs. To date, prevention programs aimed at reducing TDV perpetration have largely been universal in nature, targeting adolescents regardless of their prior TDV perpetration histories (e.g., Foshee et al., 1998; Wolfe et al., 2003). Moreover, prevention programs for TDV perpetration have largely focused on high school students, with only a few programs targeting middle school students (Whitaker et al., 2006). Based on our findings, and that of other researchers (e.g., Bonomi et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2015), primary prevention programs for TDV perpetration should begin in early adolescence (e.g., ages 12–13) in order to capture individuals prior to the onset of TDV perpetration. This is particularly true for physical TDV perpetration, which had an earlier age of onset than sexual TDV perpetration.

Our findings also suggest that primary prevention programs for different forms of TDV perpetration may need to be implemented throughout adolescence. That is, findings suggested that physical TDV perpetration onset was greatest in middle adolescence, and sexual TDV perpetration, by men specifically, was greatest in late adolescence. Following guidelines for primary prevention programs (i.e., Nation et al., 2003), effective programs should be appropriately timed. Should our findings be replicated, this would suggest that primary prevention programs may need to target different forms of TDV perpetration at different developmental time points (i.e., target physical TDV prior to middle adolescence; target sexual TDV from early-to-late adolescence). Indeed, Nation and colleagues (2003) discuss how primary prevention programs should be of sufficient dosage, which may include additional sessions or programs over time. Thus, future research is needed that examines the impact of primary prevention programs for TDV across adolescence, which may include the use of booster sessions to target risks for TDV perpetration across different developmental periods.

Finally, the current study has several limitations. One limitation is the age of first assessment which, on average, was 15. Some participants had already perpetrated TDV by this age, and thus their age of onset could not be determined. This may be especially important for the age of onset for physical TDV perpetration, which had an earlier age of onset compared to sexual TDV perpetration. Furthermore, that females and African Americans disproportionately reported previously perpetrating at baseline, gender differences for age of onset may be even more exacerbated than those reported in our study, and racial differences concerning age of onset may exist during earlier developmental epochs. Despite these limitations, we believe our study provides sound estimates concerning age of onset, as approximately 80% and 90% of adolescents had not perpetrated physical or sexual TDV at the start of the study. Still, future research should attempt to assess participants even earlier (e.g., age 12) in order to more rigorously examine the age of onset for TDV perpetration. Our indicator of TDV perpetration was dichotomous, and future research should consider examining differences between adolescents who perpetrate TDV frequently versus infrequently. Additionally, we did not examine psychosocial risk factors for the onset of TDV perpetration, or whether onset varied as a function of additional moderators (e.g., witnessing parental violence), and future research should examine these areas. We also did not examine the age of onset for other types of TDV perpetration, such as emotional/psychological aggression, which future research should examine. Finally, our sample was drawn from one specific geographic region of the U.S. Future research should examine the age(s) of onset of TDV perpetration in a nationally representative sample.

Highlights.

It is currently unknown at what age(s) the onset of teen dating violence is greatest

Findings showed the onset of physical dating violence is greatest in mid-adolescence

Findings showed the onset of sexual dating violence is greatest in late adolescence

Primary prevention for teen dating violence should begin in middle school

Acknowledgments

The current manuscript was supported, in part, by grants 2016-R2-CX-0035 and 2012-WG-BX-0005 from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) awarded to Drs. Shorey and Temple, respectively. This work was also supported, in part, by grant K24AA019707 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to Dr. Stuart. This work was also supported, in part, by grant K23HD059916 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) awarded to Dr. Temple. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NIJ.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

49.8% of the sample completed all six waves of data collection with the remaining 50.2% completing 5 or fewer waves of data collection. Thus, we compared individuals who completed all six waves to individuals who completed 5 or fewer waves. No significant differences between groups were observed for a lifetime history of sexual TDV perpetration at Wave 1; individuals who completed five or fewer waves had a significantly higher prevalence of physical TDV perpetration at Wave 1, were significantly more likely to be male, and were significantly more likely to be African American.

As discussed by Singer and Willett (2003), in cases where the onset of the phenomenon of interest does not exceed 50%, investigators can provide alternate benchmarks for the median survival time. For our study, we chose 10% as a cut-off point as across both forms of violence this benchmark was surpassed during the middle phases of data collection.

There was a small, yet significant, correlation between the onset of both physical and sexual TDV perpetration. For those who had reported not previously perpetrating physical TDV, the correlation with sexual TDV perpetration was r=0.21, p < .05. Similarly, for adolescents who reported not perpetrating sexual TDV at baseline, the correlation was r=0.24, p < .05. These findings suggest that the majority of adolescents who go on to perpetrate one form of TDV do not tend to perpetrate both forms of TDV.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bell KM, Naugle AE. Effects of social desirability on students’ self-reporting of partner abuse perpetration and victimization. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:243–256. doi: 10.1891/088667007780477348. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1891/088667007780477348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Nemeth J, Bartle-Haring S, Buettner C, Schipper D. Dating violence victimization across the teen years: Abuse frequency, number of abusive partners, and age at first occurrence. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:637–647. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple CL. Examining intergenerational violence: Violent role modeling or weak parental controls? Violence and Victims. 2003;18:143–162. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.143. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Temple JR. Do gender and exposure to interparental violence moderate the stability of teen dating violence?: Latent transition analysis. Prevention Science. 2016;17:367–376. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0621-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rue L, Polanin JR, Espelage DL, Pigott TD. A meta-analysis of school- based interventions aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research. 2017;87:7–34. doi: 10.3102/0034654316632061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HLM. Primary prevention of adolescent dating abuse perpetration: When to begin, whom to target, and how to do it. In: Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR, editors. Preventing partner violence: Research and evidence-based intervention strategies. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Ennett ST. Examination of sex and race differences in longitudinal predictors of the initiation of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2010;19:492–516. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.495032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Arriaga XB, Helms RW, Koch GG, Linder GF. An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence prevention program. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:45–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WL, Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA. The age–IPV curve: Changes in the perpetration of intimate partner violence during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44:708–726. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0158-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Hariri S, Bradley H, Gottlieb SL, Leichliter JS, Markowitz LE. Trends and patterns of sexual behaviors among adolescents and adults aged 14 to 59 years, United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2015;42:20–26. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek P, Haggerty R. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation M, Crusto C, Wandersman A, Kumpfer KL, Seybolt D, Morrissey-Kane E, Davino K. What works in prevention: Principles of effective prevention programs. American Psychologist. 2003;58:449–456. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.449. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahapetyan L, Orpinas P, Song X, Holland K. Longitudinal association of suicidal ideation and physical dating violence among high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:629–640. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner K. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Smith Slep AM. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:314–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_01. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker EM, Debnam K, Pas ET, Bradshaw CP. Exploring the link between alcohol and marijuana use and teen dating violence victimization among high school students: the influence of school context. Health Education & Behavior. 2016;43:528–536. doi: 10.1177/1090198115605308. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198115605308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears HA, Byers ES, Whelan JJ, Saint-Pierre M. “If it hurts you, then it is not a joke” Adolescents’ ideas about girls’ and boys’ use and experience of abusive behavior in dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1191–1207. doi: 10.1177/0886260506290423. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260506290423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Bell KM. A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:185–194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.003. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Brasfield H, Febres J, Stuart GL. An examination of the association between difficulties with emotion regulation and dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20:870–885. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.629342. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2011.629342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Fite PJ, Choi H, Cohen JR, Stuart GL, Temple JR. Dating violence and substance use as longitudinal predictors of adolescents’ risky sexual behavior. Prevention Science. 2015;16:853–861. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0556-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Zucosky H, Brasfield H, Febres J, Cornelius TL, Sage C, Stuart GL. Dating violence prevention programming: Directions for future interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford university press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Shorey RC, Tortolero SR, Wolfe DA, Stuart GL. Importance of gender and attitudes about violence in the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and the perpetration of teen dating violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Morrison S, Lindquist C, Hawkins SR, O’Neil JA, Nesius AM, … Reese LR. A critical review of interventions for the primary prevention of perpetration of partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:151–166. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.07.007. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman AL. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:277–293. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman AL, Grasley C, Reitzel-Jaffe D. Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: a controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:279–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.279. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Ruggiero KJ, Danielson CK, Resnick HS, Hanson RF, Smith DW, … Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of dating violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:755–762. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef5f. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]