Abstract

News coverage of novel tobacco products including e-cigarettes has framed the use of these products with both positive and negative slants. Conflicting information may shape public knowledge, perceptions of e-cigarettes, and their harms. The objective of this study is to assess effects of exposure to conflicting news coverage on US adults’ beliefs about harms and benefits of e-cigarette use. We conducted a one-way between-subjects randomized controlled experiment in 2016 to compare the effects of viewing either 1) positive, 2) negative, 3) both positive and negative (conflicting) news headlines about the safety of using e-cigarettes, or 4) no-message. Participants were 2,056 adults aged 18 and older from an online survey panel. Outcomes were beliefs about harms (3-item scale, α=0.76) and benefits (3-item scale, α=0.82) of using e-cigarettes. Participants who viewed negative headlines reported increased beliefs about harms (B=0.164, p=0.039) and lower beliefs about benefits of e-cigarette use (B=−0.216, p=0.009), compared with those in the positive headlines condition. These differences were replicated in subgroup analyses among never e-cigarette users. In addition, never e-cigarette users who viewed conflicting headlines reported lower beliefs about benefits of e-cigarette use (B=−0.221, p=0.030) than the positive headlines condition. Valence of news coverage about e-cigarettes (positive, negative, or conflicting) could influence people’s beliefs about harms and benefits of e-cigarette use.

INTRODUCTION

News coverage of health information frequently includes conflicting information about health topics including risk factors for illnesses, recommendations for disease prevention, screening, and treatments.1 Conflicting information may appear within a single news story or across distinct stories.2 In recent years, in the context of tobacco use, news coverage of novel tobacco products including e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco has framed the use of these products with both positive and negative slants. For instance, 59% of UK and Scottish newspaper articles (published between 2007 and 2012) featured e-cigarettes as a healthier choice compared with smoking conventional cigarettes, while 26% reported the potential health risks and uncertainty associated with using e-cigarettes.3 A study on US news articles about e-cigarettes (published between 1997 and 2014) reported that most articles had a mixed or neutral frame in the headline (89%) and the article (85%) about regulation, benefits, and drawbacks of e-cigarettes.4 Another content analysis of opinion articles on smokeless tobacco in US newspapers and news wires (published between 2006 and 2010) found that 64% of articles were anti-smokeless tobacco, such as focusing on the health risks of using smokeless tobacco.5 However, some articles were pro-smokeless tobacco (25%), including mentioning smokeless tobacco for harm reduction and opposing bans on smokeless tobacco use in public places.5

Conceptually, conflicting health information has been defined in several ways. Nagler conceptualized conflicting messages as those that provide information about a single behavior producing two distinct outcomes6 (e.g., coming across a news story reporting that e-cigarette use could expose smokers to fewer toxins than conventional cigarettes, while another story describes dangerously high levels of formaldehyde found in e-cigarette vapor). In contrast, Carpenter et al. defined conflicting health information as two or more health-related statements or propositions that are logically inconsistent with one another (e.g., e-cigarettes are safe versus e-cigarettes are not safe)1; someone who comes across both statements cannot simultaneously believe them to be true. Both Nagler and Carpenter et al.’s conceptualizations of conflicting health information inform the current study, since both are germane to the e-cigarette context.1,6

Studying the impact of exposure to conflicting health information surrounding e-cigarette use on consumer perceptions is both timely and important. A growing body of research points to possible adverse impacts of conflicting information on consumer decision-making, behaviors, and policy opinions in various contexts. Studies found that exposing people to conflicting information in news stories or other message-based stimuli produced outcomes including greater uncertainty about the specific stimuli topic and/or health research in general;7 increased negative attitudes toward health research;6–8 decreased self-efficacy and response efficacy;9,10 and lowered perceptions of news and scientists’ credibility.11,12

In the context of e-cigarettes, a survey among US adults found that self-reported exposure to conflicting information about e-cigarettes was associated with reduced support for certain proposed e-cigarette regulations (i.e., prohibit e-cigarette sales to youth and requiring labeling of the amount of nicotine and harmful ingredients on e-cigarette packages).13 Conflicting information exposure may lead to confusion and lower perceived harms toward e-cigarette use, and these in turn may reduce support for regulating e-cigarettes.13 Although recent articles have implicated conflicting information in shaping public knowledge and perceptions of e-cigarettes,14,15 it is not known whether exposure to conflicting information about e-cigarettes does in fact influence beliefs about e-cigarette harms and benefits.

The goal of the current study, then, is to test effects of exposure to conflicting information about e-cigarettes on US adults’ beliefs of harms and benefits about e-cigarette use. We focus on beliefs about harms and benefits as these are important factors that can influence tobacco use attitudes and behaviors.16–18 We conducted a one-way between-subjects randomized controlled experiment to compare the effects of viewing positive, negative, both positive and negative (conflicting) news headlines about e-cigarettes, or a no-message condition among US adults aged 18 years and older. Understanding the effects of conflicting e-cigarette news coverage could inform future efforts to address adverse consequences of misperceptions about e-cigarette use.

Methods

Data Collection and Study Sample

We conducted an online experiment among Survey Sampling International (SSI) panelists in February 2016. The SSI panel is an opt-in survey panel comprising US adults aged 18 and older. Participants are invited through different sources on the internet across all regions within the US. However, the panel is not designed to be representative of the general US population. Once in the panel, members are randomly invited to take part in surveys using e-mail invitations, telephone alerts, banners and messaging on web sites and online communities. This experiment was embedded as a module within a larger survey that aimed to study media usage across various health care behaviors and outcomes among the same sample of US adults (n=2,241). For this analysis, we excluded 185 participants who reported that they were not aware of e-cigarettes prior to completing the survey, yielding an eligible sample of 2,056 cases. The university’s institutional review board approved this study.

Message Stimuli Selection

Our goal for the message stimuli was to select positive and negative headlines from news coverage that conveyed opposing information about the health effects of e-cigarette use, guided by both Nagler 6 and Carpenter et al.’s 1 conceptualization of conflicting health information. We searched for relevant news headlines published between October 2013 and October 2015 by conducting keyword searches on Lexis-Nexis and ProQuest using the terms “E-cigarette”, “E-cig”, and “Vaping” and related variants. The searches included national US news sources with high circulation figures (New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, USA Today), as well as a health-specific newswire (Reuters Health Medical News) used in past tobacco-related content analyses.5,19 Sixty headlines were retrieved based on the search terms. Three undergraduate coders then independently coded the headlines. To be selected as a potential stimulus, the headline valence had to be clear (i.e., all three coders independently agreed on the valence) and succinctly address health effects of e-cigarettes, meaning that the headline referred to e-cigarettes in relation to health consequences (e.g., ‘Vaping is safer than smoking’). From those potential headlines, we selected four positive, four negative, and one neutral headline that enabled us to create conditions with conflicting health information. The four positive headlines were: 1) ‘Vaping’ is safer than smoking, 2) Smokers who switch to e-cigarettes may breathe fewer toxins, 3) E-cigarettes found to provide some benefit, and 4) British study says electronic cigarettes curb smoking risks. The four negative headlines were: 1) Unsafe e-cigarettes, 2) Lab tests hint at excess of formaldehyde in vapor from e-cigarettes, 3) E-cigarettes pose risks, and 4) Nicotine isn’t the only hazard to be found in e-cigarettes. These selected news headlines were utilized verbatim in the experiment. A neutral headline (Health and e-cigarettes) was included in each condition to help mask the true purpose of the experiment and lend ecological validity. Appendix 1 displays the headlines that comprised each message condition.

Participants were randomized to one of the following message conditions in a 1:1:1:2 ratio: 1) Positive (4 positive and 1 neutral headlines), 2) Negative (4 negative and 1 neutral headlines), 3) Conflicting (2 positive, 2 negative, and 1 neutral headlines), and 4) Control (no headlines).1 Participants were told they would be shown headlines of news stories about e-cigarettes on separate screens. The text of each headline was presented in the same font and format across conditions. They did not see the names of the newspapers or the news story. This minimized potential bias associated with viewing the publication names or differences in formatting across different stories.

Measures

Beliefs of harms from e-cigarette use

Participants were asked if they agreed with the following three statements about harms from e-cigarette use: 1) Breathing vapors from other people’s e-cigarettes is harmful to my health, 2) If I vape or use e-cigarettes every day, I will become addicted, and 3) Using e-cigarettes makes it harder for smokers to quit smoking completely.18 Responses ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree on a 5-point scale. Participants who indicated “don’t know” were coded as missing (n=189). Responses were reverse-coded such that higher scores represented stronger beliefs about harms (M=3.3, SD=1.1, Cronbach’s α=0.76).

Beliefs of benefits from e-cigarette use

Participants were next asked if they agreed with the following three statements about benefits of e-cigarette use: 1) If I vape or use e-cigarettes, it will be less harmful to me than if I smoke regular cigarettes, 2) Vaping or using e-cigarettes can help people quit smoking regular cigarettes completely, 3) Breathing vapors from other people’s e-cigarettes is less harmful to my health than breathing smoke from other people’s regular cigarettes.18 Responses were also on a 5-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and those who indicated “don’t know” were coded as missing (n=200). Responses were reverse-coded such that higher scores indicated stronger beliefs about benefits (M=3.1, SD=1.1, Cronbach’s α=0.82).

Covariates

We included questions to obtain participants’ age (categorized as 18–34, 35–54, 55 and older), gender, highest education level (categorized as high school and below, post-high school or some college, and college degree or higher), race (White, Black, or other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), household income (categorized as $34,999 and lower, $35,000 to $74,999, and $75,000 and higher), and e-cigarette use. Participants were shown a picture of different types of e-cigarettes, a brief description of e-cigarettes, and asked if they had ever tried or used e-cigarettes, even just one time. Response options were “I have never heard about e-cigarettes” (excluded from this analysis), “I have never tried them”, “I have tried them, but not the past 30 days”, and “I used them at least once in the past 30 days”.

Manipulation check variable

At the end of the experiment module, participants were asked about the valence of the headlines that they had read: “Please think about the news headlines that you read earlier. Would you say the headlines were negative, positive, or a mix of both?” Responses were on a five-point scale (completely negative, mostly negative, a mix of both, mostly positive, and completely positive). Participants who were assigned to the control condition were omitted from the manipulation check analysis.

Statistical analyses

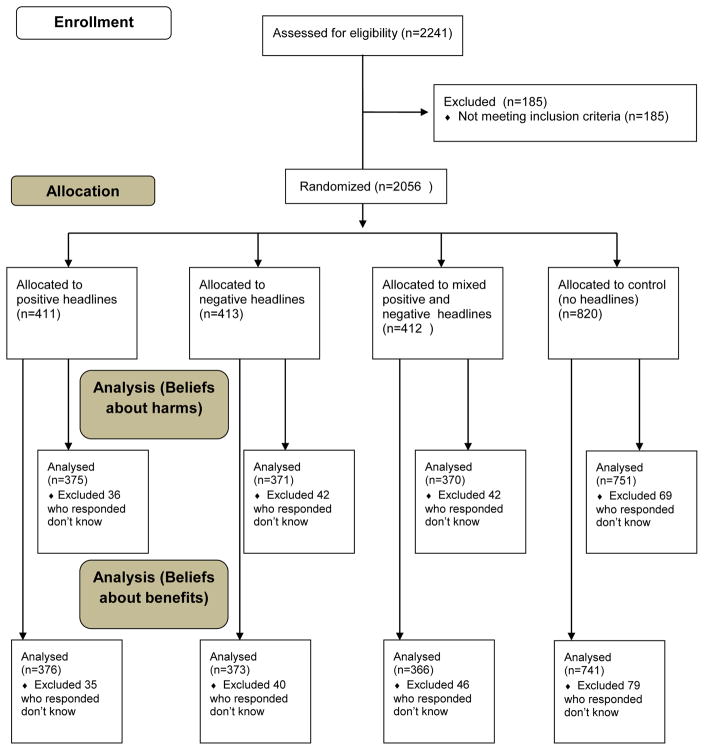

Analyses were completed in 2016. We performed univariate analyses for all study variables. Next, we analyzed whether participants across conditions differed in terms of individual characteristics. We assessed whether the manipulation was successful by comparing perceived valence across conditions. To address the study hypothesis, we utilized linear regression to predict beliefs about harms and benefits by experimental condition. There were 189 cases with missing values for beliefs of e-cigarette harms (9.2%) and 200 missing cases for beliefs of e-cigarette benefits (9.7%). We utilized complete-case analysis in the regression analyses. The final analyzed sample size was 1,867 for the regression analysis predicting beliefs of e-cigarette harms and 1,856 for the regression analysis predicting beliefs of e-cigarette benefits. Figure 1 summarizes the CONSORT flowchart and the analyzed sample in each condition. We further conducted subgroup analyses to examine the effect of experimental condition on beliefs among participants who have never tried e-cigarettes, those who have tried e-cigarettes in the past, and those who used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Figure 1.

Consort Flow Diagram.

Results

Study sample characteristics

Participants were aged 18–85 years (M=44.9, SD=15.8), 56.9% were female, 48.6% had college degrees or higher, 82.3% were White, 8.2% were African-American, 9.5% were of other races, 8.6% were of Hispanic/Latino/Spanish origin, and the median household income was $50,000 to $74,999. Most participants (64.5%) had never tried e-cigarettes, 20.5% had tried them but not in the past 30 days, and 15.0% had used e-cigarettes at least once in the past 30 days. Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics by experimental condition, and we found that only the proportion of participants of Hispanic origin differed significantly across conditions. We therefore included ethnicity in the subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Demographics of study sample by experimental condition, 2016

| Characteristics | Condition 1 (Positive) N=411 % |

Condition 2 (Negative) N=413 % |

Condition 3 (Conflicting) N=412 % |

Condition 4 (Control) N=820 % |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.843 | ||||

| 18–34 years | 31.9 | 30.5 | 32.0 | 34.3 | |

| 35–54 years | 34.1 | 35.6 | 35.7 | 34.8 | |

| 55–85 years | 34.1 | 33.9 | 32.3 | 31.0 | |

| Sex | 0.910 | ||||

| Male | 41.7 | 43.3 | 42.7 | 43.8 | |

| Female | 58.3 | 56.7 | 57.3 | 56.2 | |

| Education | 0.803 | ||||

| High school or below | 20.0 | 18.9 | 20.2 | 18.9 | |

| Post-high school or some college | 31.1 | 34.4 | 29.1 | 32.7 | |

| College degree or higher | 48.9 | 46.7 | 50.7 | 48.4 | |

| Race | 0.819 | ||||

| White | 82.2 | 83.1 | 81.3 | 82.5 | |

| African-American | 7.5 | 6.8 | 9.2 | 8.7 | |

| Other | 10.2 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 8.8 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.031 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 92.2 | 90.1 | 94.7 | 90.0 | |

| Hispanic | 7.8 | 9.9 | 5.3 | 10.0 | |

| Household Income | 0.398 | ||||

| $34999 or below | 25.3 | 29.1 | 29.9 | 28.1 | |

| $35000–$74999 | 37.5 | 39.1 | 33.0 | 36.6 | |

| $75000 or above | 37.2 | 31.8 | 37.1 | 35.3 | |

| E-cigarette Use | 0.308 | ||||

| Never tried e-cigarettes | 67.6 | 63.7 | 63.8 | 63.7 | |

| Tried but not in the past 30 days | 18.3 | 21.1 | 18.5 | 22.4 | |

| Used at least once in the past 30 days | 14.1 | 15.3 | 17.7 | 13.9 |

Notes. Young adults (18–34 years), male, high school educated or below, and Hispanic respondents were more likely to have used e-cigarettes (either tried e-cigarettes but not in the past 30 days or used e-cigarettes at least once in the past 30 days). Income and race were not associated with e-cigarette use status.

Manipulation check

Comparisons of means of valence across the positive (M=3.1, SD=0.8), negative (M=2.7, SD=0.9), and conflicting conditions (M=2.9, SD=0.8) indicated that the manipulation produced perceived valence of headlines in the expected direction (Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons were statistically significant at p<0.01).

Effect of experimental condition on beliefs of harms and benefits

Table 2 summarizes the regression analyses predicting beliefs of harms and benefits by experimental condition. The unadjusted models included only experimental condition as the predictor while the adjusted models controlled for ethnicity. Results were substantively identical across the unadjusted and adjusted models; we present the adjusted models here. Compared with participants assigned to the positive headlines condition, those who viewed negative headlines reported stronger beliefs about harms from e-cigarette use (B=0.164, p=0.039) and lower beliefs about benefits of e-cigarette use (B=−0.216, p=0.009). In addition, those in the control condition who did not view any headlines had lower beliefs of e-cigarette benefits (B=−0.178, p=0.013) compared with the positive headlines condition. Participants assigned to the conflicting headlines condition did not have significantly different beliefs about harms and benefits compared with those in the positive, negative, or control conditions.

Table 2.

Regression analysis predicting beliefs about e-cigarette harms and benefits, 2016

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Beliefs about harms | B | 95% CI | p | B | 95% CI | p |

| Experimental Condition | ||||||

| Positive (referent) | ||||||

| Negative | 0.161* | [0.006,0.316] | 0.042 | 0.164* | [0.009,0.319] | 0.039 |

| Conflicting | 0.035 | [−0.120,0.190] | 0.657 | 0.033 | [−0.122,0.188] | 0.679 |

| Control | 0.118 | [−0.016,0.251] | 0.085 | 0.120 | [−0.014,0.254] | 0.078 |

|

| ||||||

| Beliefs about benefits | B | 95% CI | p | B | 95% CI | p |

| Experimental Condition | ||||||

| Positive (referent) | ||||||

| Negative | −0.214** | [−0.376, −0.053] | 0.009 | −0.216** | [−0.377, −0.055] | 0.009 |

| Conflicting | −0.128 | [−0.290,0.034] | 0.122 | −0.127 | [−0.289,0.036] | 0.126 |

| Control | −0.176* | [−0.316, −0.036] | 0.013 | −0.178* | [−0.318, −0.038] | 0.013 |

Notes. Unadjusted models include only experimental condition in predicting beliefs. Adjusted models controlled for ethnicity.

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

Subgroup analyses

We repeated the regression analyses among never e-cigarette users, those who tried e-cigarettes but are not currently using them, and those who used them in the past 30 days, controlling for ethnicity. Table 3 summarizes the findings from these subgroup analyses. We found that beliefs about e-cigarette harms and benefits differed significantly by condition only among those who have never tried e-cigarettes. In this group, participants who viewed negative headlines reported stronger beliefs about harms (B=0.219, p=0.021) and lower beliefs about benefits (B=−0.324, p=0.001) compared to the positive headlines condition. Those who viewed conflicting headlines reported lower beliefs about benefits of e-cigarette use (B=−0.221, p=0.030) than the positive headlines condition. In addition, the control group reported stronger beliefs about harms (B=0.166, p=0.041) and lower beliefs about benefits (B=−0.210, p=0.017) compared with the positive headlines condition.

Table 3.

Regression analysis predicting beliefs about e-cigarette harms and benefits by e-cigarette use status, 2016

| Never users (n=1326) | Tried but not in the past 30 days (n=422) | Used at least once in the past 30 days (n=308) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Beliefs about harms | B | 95% CI | p | B | 95% CI | p | B | 95% CI | p |

| Experimental Condition | |||||||||

| Positive (referent) | |||||||||

| Negative | 0.219* | [0.033,0.405] | 0.021 | 0.028 | [−0.288,0.343] | 0.863 | 0.264 | [−0.156,0.685] | 0.217 |

| Conflicting | 0.048 | [−0.138,0.233] | 0.613 | 0.023 | [−0.303,0.350] | 0.889 | 0.145 | [−0.264,0.553] | 0.486 |

| Control | 0.166* | [0.007,0.325] | 0.041 | 0.042 | [−0.233,0.317] | 0.766 | 0.141 | [−0.232,0.514] | 0.458 |

|

| |||||||||

| Beliefs about benefits | B | 95% CI | p | B | 95% CI | p | B | 95% CI | p |

| Experimental Condition | |||||||||

| Positive (referent) | |||||||||

| Negative | −0.324** | [−0.523, −0.125] | 0.001 | 0.008 | [−0.306,0.322] | 0.958 | −0.268 | [−0.619,0.084] | 0.135 |

| Conflicting | −0.221* | [−0.422, −0.021] | 0.03 | −0.031 | [−0.354,0.291] | 0.849 | −0.165 | [−0.508,0.178] | 0.345 |

| Control | −0.210* | [−0.382, −0.038] | 0.017 | −0.083 | [−0.354,0.189] | 0.549 | −0.265 | [−0.579,0.048] | 0.097 |

Notes. Above models controlled for ethnicity.

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

Discussion

This study represents a first effort to compare the effects of exposure to conflicting news headlines versus positive or negative news headlines on public beliefs of the harms and benefits of e-cigarette use. We utilized an online randomized experimental design to examine these effects among a large sample of US adults. Our findings suggest that the valence of headlines (positive, negative, or conflicting) may influence people’s beliefs about harms and benefits of e-cigarette use.

The effects of valence were particularly evident for participants who had never tried e-cigarettes. Among never users, negative headlines led to stronger beliefs about harms and weaker beliefs about benefits, compared with positive headlines. However, viewing conflicting headlines appeared to have a similar effect as negative headlines in lowering never users’ beliefs about e-cigarette benefits, compared with positive headlines. This may, in turn, influence attitudes toward e-cigarette use and discourage experimentation of e-cigarette use among never users. The never users may have been exhibiting a negativity bias,20 such that the presence of two negative headlines in the conflicting information condition elicited more negative reactions toward e-cigarette use, even though they also viewed other positive and neutral headlines. Prior research has found that both negative and mixed valence frames can lead to less positive evaluations for HPV vaccines,21 and that issue involvement can moderate effects of valence framing.22

The public health implications of these observed effects of conflicting e-cigarette news headlines on public beliefs depend, in part, on the tobacco use behaviors of individuals. For those who do not use any form of tobacco, these results could be encouraging, as they suggest these consumers would be more skeptical of e-cigarette benefits and may be less willing to try using e-cigarettes. For those who are trying to quit using combustible tobacco (e.g., cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos), the implications are more nuanced. On the one hand, a recent systematic review of 38 studies reported that use of e-cigarettes may be associated with lower success of smoking cessation.23 Conflicting information may reduce smokers’ beliefs of e-cigarette benefits and may steer them toward using evidence-based treatments (e.g., nicotine replacement therapy). On the other hand, a longitudinal study found that US smokers who used e-cigarettes over two years had a higher rate of quit attempts and cessation rate than short-term e-cigarette users or non-users.24 E-cigarettes may also help smokers to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked.25,26 Conflicting information may therefore deter smokers from switching to a potentially less harmful product if they are unable to quit using conventional treatment.

In contrast to never users, valence of headlines did not appear to influence beliefs among those who tried or are currently using e-cigarettes. One possible explanation is that e-cigarette users may have solidified their beliefs about benefits and harms of e-cigarette use based on their personal experience with these products. They may also have more knowledge about e-cigarettes, and therefore their beliefs are less likely to be influenced by brief exposures to news headlines, compared with never users. Effects of valence in headlines may also have greater effects among those not personally involved in the behavior, and who thus may rely on more heuristic approaches to information processing.27

This study contributes new insights to inform future research on the effects of exposure to conflicting and contradictory health information, including about tobacco use. Specifically, we offer new empirical evidence to support the hypothesis that exposure to conflicting information could be related to observed trends in public knowledge and greater perceived harms associated with e-cigarette use over time.14,15 This analysis further adds to the growing body of research establishing associations between exposure to conflicting information and cognitions or behavior in other health domains (e.g., nutrition, HPV vaccination).7,10 Future research could explore other outcomes of exposure to conflicting e-cigarette information, which have been explored in other health domains, including public perceptions of uncertainty or confusion about e-cigarettes, perceived trust and credibility of science/health recommendations, and tobacco use behaviors. We also suggest exploring whether these results would be replicated for other health issues that feature conflicting information (e.g., marijuana use, vaccines).

We recognize that this study is limited in several ways. First, we operationalized conflicting information exposure as a single episode of forced exposure to brief news headlines about one topic (health effects) related to e-cigarette use. The conflicting information condition comprised one neutral, two positive, and two negative headlines. Due to the need to minimize respondent burden, we decided to limit the experimental stimuli to five brief headlines. We did not include the entire news articles in this study. Headlines are particularly influential and exert a framing influence.28 Moreover, when people scan news, they often focus on headline and visual elements in news stories.29 However, the focus on headlines may have limited the amount of exposure to conflicting content about e-cigarette use, such that the manipulation did not sufficiently generate perceptions of conflict to influence participants’ beliefs. Future research could assess the impact of additional exposures to conflicting information by increasing the number of headlines, including the news stories, and utilizing repeated exposures to conflicting information over multiple episodes. In addition, this study focuses on immediate effects of headlines on beliefs about e-cigarettes. Future studies could evaluate whether changes in beliefs about e-cigarette harms and benefits emerge after a time delay (i.e., sleeper framing effects).30

Second, to maximize internal validity we presented the headlines as plain text, stripped of their original fonts and formatting. One advantage for this approach is to minimize variation in message format or structural features compared with viewing headlines on print newspapers or online news websites, which could interfere with attention and information processing. This permits stronger inferences that differences in the beliefs were due to the valence of the headlines and conflicting information, and not some other extraneous factors. The disadvantage, however, is participants were viewing the news headlines under artificial contexts. It is possible that effects of news headlines depend on both the appearance and the content. Future research should consider experiments that display the message stimuli in the form of actual news headlines to assess the external validity of the study’s findings and control for format and structural features in these settings.

Third, the SSI opt-in panel is not representative of the general US adult population. For instance, over 80% of the participants were white and over 90% were non-Hispanic. This suggests that there may be selection bias in participation in the panel. Despite these limitations, opt-in panels have been used successfully in online experimental research31–33 because they offer better diversity than student-based samples. This study serves as a model for conducting future studies to replicate this research among more diverse and representative samples, including vulnerable populations with higher tobacco use prevalence (e.g., youth, young adults, and racial/ethnic minorities).

Fourth, we did not measure smoking status of participants. Future research could assess specifically how current smokers, dual-users of conventional cigarettes and e-cigarettes, and non-users of both products respond to conflicting information about e-cigarettes. This information will be useful to better understand the public health implications of conflicting news coverage of e-cigarettes on these populations.

In sum, this study provides evidence from an online experiment that conflicting health information in the news may influence individuals’ beliefs about potential harms and benefits in the context of e-cigarette use. Although the effect appears to be small and limited to those who have no prior experience with using e-cigarettes, at the population level, the impact of conflicting health information could lead to meaningful effects on downstream outcomes including tobacco use behaviors.

Highlights.

In an experiment, participants viewed news headlines about e-cigarettes.

Outcomes were beliefs about harms and benefits of using e-cigarettes.

Negative headlines increased beliefs about harms and reduced beliefs about benefits.

Conflicting headlines reduced beliefs about benefits of e-cigarette use among never users.

Valence of news coverage about e-cigarettes could influence people’s beliefs about e-cigarette use.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was funded by the World-Leading University Fostering Program at Seoul National University, the Institute of Communication Research at Seoul National University, and Grant #2016016761 from the National Research Foundation of Korea, awarded to C.J. Lee as principal investigator. R.H. Nagler acknowledges support from the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Institute on Aging, administered by the University of Minnesota Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health [grant number 2 K12-HD055887]. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsors. The funders have no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

We would like to thank our undergraduate coders: Christine Kausal, Gail Fernandes, and Kathryn Wesoloski.

Appendix 1 – Message stimuli within each condition

| Condition 1 Positive |

Condition 2 Negative |

Condition 3 Conflicting |

Condition 4 No-message control |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Vaping’ is safer than smoking | Unsafe e-cigarettes | Randomly selected two positive headlines | - |

| Smokers who switch to e-cigarettes may breathe fewer toxins | Lab tests hint at excess of formaldehyde in vapor from e-cigarettes | - | |

| E-cigarettes found to provide some benefit | E-cigarettes pose risks | Randomly selected two negative headlines | - |

| British study says electronic cigarettes curb smoking risks | Nicotine isn’t the only hazard to be found in e-cigarettes | - | |

| Health and e-cigarettes (neutral) | Health and e-cigarettes (neutral) | Health and e-cigarettes (neutral) | - |

Footnotes

We included a larger no-headlines control group compared with the other message conditions for a separate study objective that is not part of the current analysis.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carpenter DM, Geryk LL, Chen AT, Nagler RH, Dieckmann NF, Han PKJ. Conflicting health information: a critical research need. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1111/hex.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagler RH, LoRusso S. Conflicting information and message competition in health and risk messaging. In: Parrott R, editor. Encyclopedia of Health and Risk Message Design and Processing. New York, NY: New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rooke C, Amos A. News media representations of electronic cigarettes: An analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK and Scotland. Tob Control. 2014;23(6):507–512. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yates K, Friedman K, Slater MD, Berman M, Paskett E, Ferketich AK. A content analysis of electronic cigarette portrayal in newspapers. Tob Regul Sci. 2015;1(1):94–102. doi: 10.18001/TRS.1.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wackowski OA, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD, Ling PM. A content analysis of smokeless tobacco coverage in U.S. newspapers and news wires. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(7):1289–1296. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagler RH. Adverse outcomes associated with media exposure to contradictory nutrition messages. J Health Commun. 2014;19(1):24–40. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.798384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang C. Motivated Processing: How People Perceive News Covering Novel or Contradictory Health Research Findings. Sci Commun. 2015;37(5):602–634. doi: 10.1177/1075547015597914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, Nagler RH, Wang N. Source-specific Exposure to Contradictory Nutrition Information: Documenting Prevalence and Effects on Adverse Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes. Health Commun. 2017 Feb;:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1278495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall L, Comello ML. Stymied by a wealth of health information: How viewing conflicting information online diminishes efficacy. AEJMC National Conference; 2016; 2016. [Accessed January 8, 2017]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306105287_Stymied_by_a_wealth_of_health_information. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nan X, Daily K. Biased Assimilation and Need for Closure: Examining the Effects of Mixed Blogs on Vaccine-Related Beliefs. J Health Commun. 2015;20(4):462–471. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.989343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen JD, Hurley RJ. Conflicting stories about public scientific controversies: Effects of news convergence and divergence on scientists’ credibility. Public Underst Sci. 2012;21(6):689–704. doi: 10.1177/0963662510387759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen JD. Scientific Uncertainty in News Coverage of Cancer Research: Effects of Hedging on Scientists’ and Journalists’ Credibility. Hum Commun Res. 2008;34(3):347–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2008.00324.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan ASL, Lee C, Bigman CA. Public support for selected e-cigarette regulations and associations with overall information exposure and contradictory information exposure about e-cigarettes: Findings from a national survey of U.S. adults. Prev Med. 2015;81:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowin M, Cheney MK, Wann TF. Knowledge and Beliefs About E-Cigarettes in Straight-to-Work Young Adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 Jul;:ntw195. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majeed BA, Weaver SR, Gregory KR, et al. Changing Perceptions of Harm of E-Cigarettes Among U.S. Adults, 2012–2015. Am J Prev Med. 2016;0(0) doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan E, Gibson L, Momjian A, Hornik RC. Are Young People’s Beliefs About Menthol Cigarettes Associated With Smoking-Related Intentions and Behaviors? Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(1):81–90. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song AV, Glantz SA, Halpern-Felsher BL. Perceptions of second-hand smoke risks predict future adolescent smoking initiation. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(6):618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan ASL, Lee C, Bigman CA. Comparison of beliefs about e-cigarettes’ harms and benefits among never users and ever users of e-cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wackowski OA, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD, Ling PM. Smokeless Tobacco Risk Comparisons and Other Debate Messages in the News. Health Behav Policy Rev. 2014;1(3):183–190. doi: 10.14485/HBPR.1.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozin P, Royzman EB. Negativity Bias, Negativity Dominance, and Contagion. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2001;5(4):296–320. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0504_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigman CA, Cappella JN, Hornik RC. Effective or ineffective: Attribute framing and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(Supplement 1):S70–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gesser-Edelsburg A, Walter N, Shir-Raz Y, Green MS. Voluntary or Mandatory? The Valence Framing Effect of Attitudes Regarding HPV Vaccination. J Health Commun. 2015;20(11):1287–1293. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(2):116–128. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhuang Y-L, Cummins SE, Sun JY, Zhu S-H. Long-term e-cigarette use and smoking cessation: a longitudinal study with US population. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 1):i90–i95. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Hajek P. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014. [Accessed July 20, 2015]. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Mnatzaganian G, Worrall-Carter L. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT, Goldman R. Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;41(5):847–855. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.41.5.847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tannenbaum PH. The Effect of Headlines on the Interpretation of News Stories. Journal Bull. 1953;30(2):189–197. doi: 10.1177/107769905303000206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmqvist K, Holsanova J, Barthelson M, Lundqvist D. Reading or scanning? A study of newspaper and net paper reading. Mind. 2003;2(3):4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaac MS, Poor M. The sleeper framing effect: The influence of frame valence on immediate and retrospective judgments. J Consum Psychol. 2016;26(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2015.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niederdeppe J, Heley K, Barry CL. Inoculation and Narrative Strategies in Competitive Framing of Three Health Policy Issues. J Commun. 2015;65(5):838–862. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maloney EK, Cappella JN. Does vaping in e-cigarette advertisements affect tobacco smoking urge, intentions, and perceptions in daily, intermittent, and former smokers? Health Commun. 2016;31(1):129–138. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.993496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim AE, Lee YO, Shafer P, Nonnemaker J, Makarenko O. Adult smokers’ receptivity to a television advert for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob Control. 2013 Oct; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051130. tobaccocontrol-2013-051130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]