Abstract

Background

The literature on patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) and patient experience is somewhat mixed. Government and private payers are promoting multi-payer PCMH initiatives to align requirements and resources and to enhance practice transformation outcomes. To this end, the multipayer Michigan Primary Care Transformation (MiPCT) demonstration project was carried out.

Objective

To examine whether the PCMH is associated with a better patient experience, and whether a mature, multi-payer PCMH demonstration is associated with even further improvement in the patient experience.

Design

This is a cross-sectional comparison of adults attributed to MiPCT PCMH, non-participating PCMH, and non-PCMH practices, statistically controlling for potential confounders, and conducted among both general and high-risk patient samples.

Participants

Responses came from 3893 patients in the general population and 4605 in the high-risk population (response rates of 31.8% and 34.1%, respectively).

Main Measures

The Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey, with PCMH supplemental questions, was administered in January and February 2015.

Key Results

MiPCT general and high-risk patients reported a significantly better experience than non-PCMH patients in most domains. Adjusted mean differences were as follows: access (0.35**, 0.36***), communication (0.19*, 0.18*), and coordination (0.33**, 0.35***), respectively (on a 10-point scale, with significance indicated by: *= p<0.05, **= p<0.01, and ***= p<0.001). Adjusted mean differences in overall provider ratings were not significant. Global odds ratios were significant for the domains of self-management support (1.38**, 1.41***) and comprehensiveness (1.67***, 1.61***). Non-participating PCMH ratings fell between MiPCT and non-PCMH across all domains and populations, sometimes attaining statistical significance.

Conclusions

PCMH practices have more positive patient experiences across domains characteristic of advanced primary care. A mature multi-payer model has the strongest, most consistent association with a better patient experience, pointing to the need to provide consistent expectations, resources, and time for practice transformation. Our results held for a general population and a high-risk population which has much more contact with the healthcare system.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4139-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: patient experience, PCMH, multi-payer, primary care, CAHPS

INTRODUCTION

Background and Rationale

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model has been widely promoted for its potential to improve the quality and value of care, as well as patient experience.1 , 2 PCMH evaluations focus on both the general population and high-risk subpopulations with medical comorbidities, who may disproportionally benefit from PCMH components such as care coordination.3 , 4

Evidence reviews suggest that the hypothesized gains have yet to be fully realized.5 , 6 Some investigators have found better experiences for patients in at least some measures in PCMH practices,7 – 12 while others report little or no difference from traditional practices,13 – 18 leading some to doubt the potential for PCMH transformation as a means of achieving reliable improvements in experience of care.18 One possible explanation for the inconclusive findings is that they may reflect evaluations of partial PCMH implementation or evaluations taking place during the initial phases of PCMH transformation, when change can be hard on both providers and patients.14 , 15

Increasingly, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and other payers are coming together in multi-payer initiatives based on the idea that alignment across payers will provide more resources and sharpen provider focus to accelerate change.19 , 20 The effects of these demonstrations on patient experience have yet to appear in the peer-reviewed literature, but some publicly available results still present a mixed picture.21 – 23 The Michigan Primary Care Transformation (MiPCT) is possibly the largest multi-payer PCMH initiative in the country, with five participating payers (Medicare, Medicaid, and three commercial payers) and over 1.2 million patients (12% of the state’s population). Thus MiPCT is an excellent context in which to study the relationship between a well-supported and mature PCMH program and patient experience.

Objectives

The current study contributes to the literature by comparing the care experience of patients in a multi-payer PCMH demonstration relative to patients not served by PCMH. Moreover the study is designed with a second comparison group—patients served by newer PCMH practices that are not part of the demonstration, and therefore have fewer resources for transformation. We expect the greatest difference in experience to be between patients cared for by the mature, well-resourced practices in the MiPCT demonstration and the non-PCMH practices. We expect patients served by non-participating PCMHs to rate their experiences somewhere in between these two groups.

METHODS

Study Design

This study is a cross-sectional comparison employing a multi-mode survey of patient experience. Comparison practices were selected in 2012 as part of the overall MiPCT evaluation design. From MiPCT and comparison practices, stratified random sampling was utilized to select patients with oversampling based on high medical risk. The project was reviewed according to the protocols of the Michigan Public Health Institute (MPHI) Institutional Review Board and determined to be non-human subject research.

MiPCT PCMH Settings

MiPCT began with a planning year in 2011, and became operational in January 2012. The demonstration, originally designed for 3 years, was subsequently extended to continue through 2016. Practices eligible to participate in MiPCT all had PCMH designation in 2010 from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) Physician Group Incentive Program (PGIP).24 , 25 This included 395 primary care practices and a participating provider base of 1900 physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. These practices represent a wide variety of settings (health system-owned, physician-owned and jointly- owned), sizes, and environments (rural, urban, suburban), including 11 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs).

The MiPCT payment model includes enhanced payment for practice transformation and embedded care management, and quality performance-based incentives. Practices were contractually obligated to 1) maintain either BCBSM or National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) designation for the duration of the demonstration; 2) provide care management services using a ratio of two trained MiPCT Care Managers per 5000 patients; 3) maintain an all-patient registry to identify gaps in care and review performance dashboards; and 4) implement advanced access processes including 24/7 access to a clinical decision-maker, open-access scheduling, and options for care outside of business hours. MiPCT supplied practice transformation support for training and embedding Care Managers. Training topics addressed the MiPCT goals of 1) risk reduction for healthy individuals, 2) self-management support to prevent patients with moderate chronic disease levels from progressing to the complex category, 3) care coordination and support for patients with complex chronic diseases, 4) initiation of timely transition of care activities when patients experience emergency room or inpatient visits, and 5) coordinated end-of-life care.

Non-Participating PCMH Settings

Even as MiPCT supported enhanced transformation among participating PCMHs, private payers continued to recognize and reimburse new practices that achieved PCMH designation. Between 2010 and 2015, PCMH designations by BCBSM rose from 1647 to 4349 providers; NCQA designations rose from 185 in 2013 to 450 in 2015 (including both MiPCT and non-MiPCT PCMH providers). A key difference between non-MiPCT and MiPCT PCMHs (other than the enhanced resources and longer experience with designation as already described) is the lack of a payment model that specifically reimbursed for care management services. Because all MiPCT practices were designated by BCBSM (sometimes in addition to NCQA), comparison PCMH practices were limited to those with 2011 or 2012 BCBSM PCMH designation and not eligible for MiPCT (a total of 539 practices).

Non-PCMH Settings

A second comparison study setting of non-PCMH practices was selected using propensity score matching from all 1474 non-PCMH practices on the BCBSM PGIP list. Matching variables included observable practice characteristics that were available at the time, such as practice size, Medicaid and commercial patient volume, average patient risk scores, FQHC status, and urban/rural location (see online Appendix for methods and results of the matching procedure).

Participants

Survey respondents were selected from lists of patients attributed to practices in each study group. The sampling frame was further limited based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) a documented patient visit (in payer claims/encounter files) with their attributed/assigned primary care provider (PCP) during the year prior to the survey, and 2) age of 18 years or older as of survey implementation.

Sampling strata were defined by participating payer and study group. This led to 15 cells (three study groups and five payers), from which a random sample was selected, with the goal of achieving 250 completed surveys per cell. The actual sample size per cell was inflated based on known variation in response rates for each payer.

In addition, the study design called for an oversampling of high-risk patients with severe or chronic conditions. The number of the additional high-risk patients sampled for each stratum varied from payer to payer, as each payer had different proportions of high-risk patients. The supplemental high-risk samples, together with high-risk patients in the general population sample, made up the high-risk patient sample for additional analyses.

Surveys were fielded in January and February of 2015 by an NCQA-certified Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) vendor. Two waves of mailings were completed, with postcard reminders sent to non-respondents. Non-respondents were then called and given the option to complete the survey over the phone. Figure S1 in the online Appendix illustrates the flow of activities to construct the sample.

Variables and Measurement

The CAHPS surveys have become the gold standard for assessing patient experience in ambulatory care practices,26 – 30 and are particularly well-suited for evaluating the impact of healthcare innovations.31 The PCMH supplemental item set was released in late 2011, so not all prior research on patient experience and PCMH utilized CAHPS. Much of the published validation work has occurred within the last 5 years.27 , 29 , 30 We fielded the survey at a time when NCQA was collecting information on proposed changes to the Clinician and Group (CG)-CAHPS 2.0 instrument and PCMH 2.0 item set. The study included items consistent with those recommended changes, not all of which were carried forward into the subsequent CG-CAHPS and PCMH 3.0 item set. This manuscript groups the items gathered to be consistent with the current CAHPS PCMH 3.0 domains (Table 1) including access to care, provider communication, care coordination, self-management support, comprehensiveness, and provider rating. We rescaled all items to a common 0–10 scale and computed composite scores for the first three domains following published methods for the employment of CAHPS measures in group comparisons,32 described in more detail in the online Appendix. The sixth domain, the provider rating, was assessed by a single item.

Table 1.

CAHPS Survey Measures of Patients’ Experiences with Care According to Domain

| Original | ||

|---|---|---|

| Short Item Title | Scale | CG-CAHPS Source |

| Access (Getting Timely Appointments, Care, and Information) | ||

| Patient got appointment for urgent care as soon as needed | 1–4 | Core 3.0, #6 |

| Patient got appointment for non-urgent care as soon as needed | 1–4 | Core 3.0, #8 |

| Patient got answer to medical question the same day he/she phoned provider’s office | 1–4 | Core 3.0, #10 |

| Patient got answer to medical question as soon as he/she needed when phoned provider’s office after hours | 1–4 | Core 2.0, #12 |

| Communication (How Well Providers Communicate with Patients) | ||

| Provider explained things in a way that was easy to understand | 1–4 | Core 3.0, #11 |

| Provider listened carefully to patient | 1–4 | Core 3.0, #12 |

| Care Coordination (Providers Use of Information to Coordinate Patient Care) | ||

| Provider knew important information about patient’s medical history | 1–4 | Core 3.0, #13 |

| Someone from provider’s office followed up with patient to give results of blood test, x-ray, or other test | 1–4 | Core 3.0, #17 |

| Provider seemed informed and up to date about care from specialists | 1–4 | PCMH 3.0, #3 |

| Rating (Rating of Provider) | ||

| Using a number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst provider possible and 10 is the best provider possible, what number would you use to rate this provider? | 0–10 | Core 3.0, #18 |

| Self-Management Support (Provider’s Office) | ||

| Anyone in provider’s office talked with patient about specific health goals‡ | Yes/no | PCMH 3.0, #4 |

| Anyone in provider’s office asked if there were things that made it hard for patient to take care of health‡ | Yes/no | PCMH 3.0, #5 |

| Comprehensiveness (Provider’s Office) | ||

| Anyone in provider’s office asked if patient had felt sad, empty, or depressed‡ | Yes/no | General Suppl. 3.0 |

| Anyone in provider’s office talked about worrying/stressful aspects of patient’s life‡ | Yes/no | PCMH 3.0, #6 |

*CG-CAHPS = Clinician & Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

†For numeric scores, scales range from 0 (worst) to 10 (best) or from 1 (never) to 4 (always)

‡The “Anyone” referent has been changed to “Somebody” in version 3.0

Covariates included individual-level variables of education, race, insurance payer, and concurrent risk group. Covariates also included practice-level variables: practice size, hospital employment, and urban/rural location. Education and race were measured in the demographic section of the survey. Concurrent risk scores ranging from 0 to 99,999 were calculated from claims data using the Verisk Analytics DxCG RiskSmart software and served as proxy measures of morbidity and overall health status (Verisk Health/Verscend Technologies, Inc., Waltham, MA). Based on criteria provided by the analytics vendor, high- to very high-risk patients have scores 226 or above, indicating that they are heavy utilizers of the healthcare system, most often being treated for multiple high-severity acute conditions and/or chronic conditions. The concurrent risk score is based on both acute and chronic diagnoses grouped based on cost, as well as gender and age. Additional information about risk scores is included in the online Appendix.

Practice size was defined as the number of primary care providers in the practice unit. For the geography variable, urban was defined in contrast to rural, in alignment with the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy as a practice census tract with Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) designations. Hospital employment is a binary practice-level covariate; 85% of providers are employed by a hospital.

Statistical Methods

We used the Complex Samples module in IBM SPSS version 23 software to conduct data processing and analysis. We first computed sampling weights that corrected for non-response and sample design. Then, via the CSPLAN procedure, we programmed the following: 1) data stratification, 3) data clustering at the practice level, and 3) sampling weights in the Complex Samples module. The resultant file was used in all subsequent analyses to account for the actual numbers of respondents within strata and for potential clustering effects when calculating standard errors.33 The general linear model (CSGLM) procedure was employed for the four continuous outcome variables (access, coordination, communication, and provider rating), with post hoc comparisons to assess differences among MiPCT and comparison groups. Ordinal regression with the logit link function (CSORDINAL model) was used for the domains of self-management support and comprehensiveness (which can take only three values and therefore are not continuous). Both models controlled for potential confounding variables including race, education, payer group (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial insurance), health risk (very low, low, medium, high, very high), practice size, hospital ownership, and geography (urban, rural).

RESULTS

The final samples include 3893 patients from the general population served by 802 practices, and 4605 high-risk patients served by 829 practices (Tables 2 and 3). The overall response rate for the survey was 31.8% for the general population and 34.1% for the high-risk population. This response rate is typical for CAHPS mail surveys.34 A total of 95 surveys, almost equally distributed across study groups, were completed by phone, representing 1.5% of all respondents. We examined non-response as a potential source of bias. Consistent with previous studies, non-response bias tests revealed that respondents were more likely to be female, older, on Medicare, and in the high-risk group. There were no significant differences in response rates among the MiPCT (32.9%), non-participating PCMH (32.3%), and non-PCMH (32.8%) patients.

Table 2.

Intervention and Comparison Group Characteristics: General Population

| MiPCT (n=1291) | PCMH (n=1310) | Non-PCMH (n=1292) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18–34 | 117 | 9.2% | 108 | 8.4% | 92 | 7.2% |

| 35–44 | 118 | 9.3% | 119 | 9.3% | 113 | 8.9% |

| 45–54 | 245 | 19.3% | 235 | 18.3% | 257 | 20.2% |

| 55–64 | 398 | 31.3% | 431 | 33.5% | 461 | 36.2% |

| 65+ | 394 | 31.0% | 392 | 30.5% | 350 | 27.5% |

| Women | 792 | 61.3% | 774 | 59.1% | 738 | 57.1% |

| Education | ||||||

| Some high school or less | 102 | 8.1% | 112 | 8.8% | 133 | 10.5% |

| High school grad/GED | 348 | 27.5% | 377 | 29.7% | 393 | 31.1% |

| Some college | 443 | 35.0% | 444 | 35.0% | 421 | 33.4% |

| Four-year college degree | 186 | 14.7% | 163 | 12.8% | 155 | 12.3% |

| College graduate plus | 188 | 14.8% | 173 | 13.6% | 160 | 12.7% |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1080 | 85.6% | 1052 | 82.4% | 1018 | 81.2% |

| African-American | 104 | 8.2% | 138 | 10.8% | 136 | 10.9% |

| Hispanic | 28 | 2.2% | 31 | 2.4% | 36 | 2.9% |

| Other | 49 | 3.9% | 56 | 4.4% | 63 | 5.0% |

| Payer | ||||||

| Medicaid | 185 | 14.3% | 193 | 14.7% | 215 | 16.6% |

| Medicare | 371 | 28.7% | 361 | 27.6% | 338 | 26.2% |

| Commercial | 735 | 56.9% | 756 | 57.7% | 739 | 57.2% |

| Risk Group | ||||||

| Very low | 81 | 6.3% | 99 | 7.6% | 104 | 8.0% |

| Low | 137 | 10.6% | 162 | 12.4% | 161 | 12.5% |

| Medium | 321 | 24.9% | 344 | 26.3% | 314 | 24.3% |

| High | 471 | 36.5% | 469 | 35.8% | 473 | 36.6% |

| Very high | 279 | 21.6% | 236 | 18.0% | 240 | 18.6% |

| Practice Characteristics of Patient Respondents* | ||||||

| Urban | 1073 | 82.7% | 1064 | 81.3% | 1071 | 82.9% |

| Employed by Hospital | 437 | 34.1% | 305 | 23.3% | 199 | 15.4% |

| Practice Size by no. of PCPs † | ||||||

| 1–2 | 364 | 28.3% | 610 | 46.6% | 681 | 52.7% |

| 3–4 | 335 | 26.1% | 368 | 28.1% | 328 | 25.4% |

| 5–7 | 327 | 25.5% | 237 | 18.1% | 195 | 15.1% |

| 8–11 | 174 | 13.6% | 48 | 3.7% | 40 | 3.1% |

| 12 or more | 84 | 6.5% | 47 | 3.6% | 48 | 3.7% |

*Practice information is summarized at the patient level. The number of practices represented in each group of respondents is 281 (MiPCT), 358 (non-participating PCMH), and 163 (non-PCMH), for a total of 802

†Treated as a continuous variable in the mixed model analysis

PCP primary care provider

Table 3.

Intervention and Comparison Group Characteristics: High-Risk Population

| MiPCT (n=1541) | PCMH (n=1542) | Non-PCMH (n=1522) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18–34 | 95 | 6.0% | 78 | 5.1% | 64 | 4.3% |

| 35–44 | 101 | 6.4% | 114 | 7.5% | 106 | 7.1% |

| 45–54 | 280 | 17.8% | 259 | 17.0% | 257 | 17.1% |

| 55–64 | 593 | 37.7% | 624 | 41.0% | 640 | 42.6% |

| 65+ | 504 | 32.0% | 446 | 29.3% | 434 | 28.9% |

| Women | 995 | 62.3% | 962 | 62.3% | 900 | 59.1% |

| Education | ||||||

| Some high school or less | 118 | 7.5% | 134 | 9.1% | 150 | 10.1% |

| High school grad/GED | 446 | 28.4% | 445 | 30.2% | 468 | 31.4% |

| Some college | 540 | 34.4% | 532 | 35.3% | 516 | 34.7% |

| Four-year college degree | 202 | 12.9% | 179 | 11.9% | 157 | 10.5% |

| College graduate plus | 263 | 16.8% | 202 | 13.4% | 198 | 13.3% |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1335 | 85.5% | 1246 | 83.0% | 1208 | 81.8% |

| African-American | 134 | 8.6% | 168 | 10.8% | 162 | 11.0% |

| Hispanic | 35 | 2.2% | 45 | 3.0% | 41 | 2.8% |

| Other | 58 | 3.7% | 48 | 3.2% | 65 | 4.4% |

| Payer | ||||||

| Medicaid | 275 | 17.0% | 241 | 15.6% | 276 | 18.1% |

| Medicare | 440 | 27.6% | 384 | 22.9% | 371 | 24.4% |

| Commercial | 882 | 55.2% | 920 | 59.5% | 875 | 57.5% |

| Risk Group | ||||||

| 1074 | 67.3% | 1068 | 69.1% | 1080 | 71.0% | |

| 523 | 36.3% | 477 | 30.9% | 442 | 29.0% | |

| Practice Characteristics of Patient Respondents* | ||||||

| Urban | 1328 | 83.7% | 1254 | 81.2% | 1272 | 83.6% |

| Employed by Hospital | 532 | 34.3% | 355 | 23.0% | 218 | 14.3% |

| Practice Size by no. of PCPs † | ||||||

| 1–2 | 437 | 28.4% | 704 | 45.7% | 765 | 50.3% |

| 3–4 | 389 | 25.2% | 430 | 27.9% | 441 | 29.0% |

| 5–7 | 349 | 22.6% | 285 | 18.5% | 219 | 14.4% |

| 8–11 | 253 | 16.4% | 68 | 4.4% | 48 | 3.2% |

| 12 or more | 113 | 7.3% | 55 | 3.6% | 49 | 3.2% |

*Practice information is summarized at the patient level. The number of practices represented in each group of respondents is 290 (MiPCT), 380 (non-participating PCMH), and 159 (non-PCMH), for a total of 829

†Treated as a continuous variable in the mixed model analysis

PCP primary care provider

Unadjusted demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, gender, race, level of education, risk group, urban/rural, and payer, are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Within the general population, analyses (described in the online Appendix) revealed no significant between-group differences in demographic characteristics. Within the high-risk population, only education was a significant between-group patient demographic difference. However, in both the general and high-risk populations, there were pronounced significant study group differences for two of the practice characteristics, including practice size and employment.

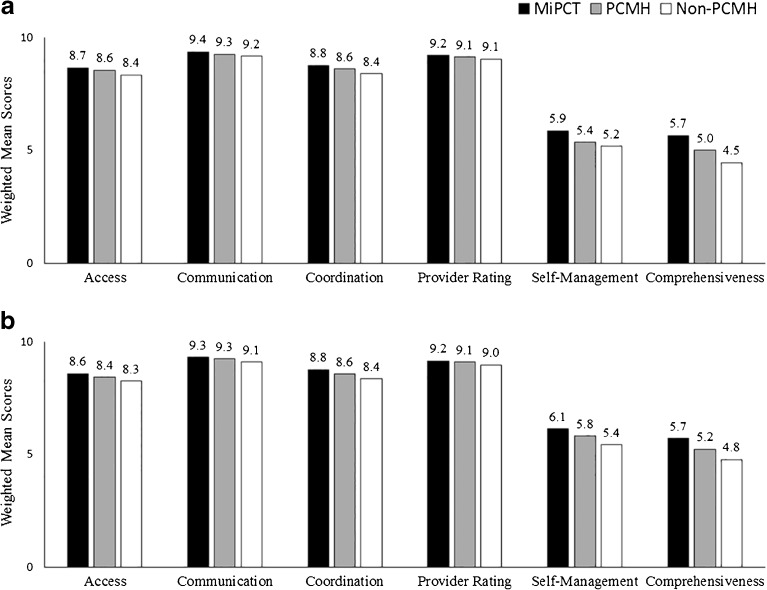

Figure 1a and b displays the weighted mean ratings by domain and study group for the general population and high-risk group, respectively. Table 4 (top) contains the adjusted mean difference between MiPCT and comparison-group patients for the domains of access, communication, coordination, and provider rating. Table 4 also presents the odds ratios for group comparisons in the domains of self-management support and comprehensiveness. MiPCT patients reported significantly better experiences in five of the six domains: access, communication with provider, coordination, self-management support, and comprehensiveness. Patients of non-participating PCMH practices reported significantly better experiences than non-PCMH patients in three domains: access, coordination, and comprehensiveness. Finally, MiPCT patients reported significantly better experiences than non-participating PCMH patients in two domains: comprehensiveness and self-management support.

Figure 1.

Weighted mean patient experience scores by domain for the general (a) and high-risk (b) study populations.

Table 4.

Comparison of MiPCT and Non-Participating PCMH and Non-PCMH Comparison Groups by Patient Experience Domain

| MiPCT vs. PCMH | MiPCT vs. non-PCMH | PCMH vs. non-PCMH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Population | ||||||

| Difference | P | Difference | P | Difference | P | |

| Access | 0.11 | 0.243 | 0.35** | 0.001 | 0.24* | 0.019 |

| Communication | 0.09 | 0.233 | 0.19* | 0.024 | 0.10 | 0.203 |

| Coordination | 0.12 | 0.225 | 0.33** | 0.002 | 0.21* | 0.046 |

| Provider rating | 0.04 | 0.576 | 0.12 | 0.095 | 0.08 | 0.227 |

| Odds ratio | P | Odds ratio | P | Odds ratio | P | |

| Self-management | 1.25* | 0.019 | 1.38** | 0.001 | 1.10 | 0.323 |

| Comprehensiveness | 1.36** | 0.001 | 1.67*** | <0.001 | 1.23* | 0.043 |

| High-Risk Population | ||||||

| Difference | P | Difference | P | Difference | P | |

| Access | 0.17* | 0.049 | 0.36*** | <0.001 | 0.18* | 0.043 |

| Communication | 0.05 | 0.486 | 0.18* | 0.016 | 0.13 | 0.069 |

| Coordination | 0.17* | 0.050 | 0.35*** | <0.001 | 0.18* | 0.047 |

| Provider rating | 0.03 | 0.674 | 0.12 | 0.055 | 0.10 | 0.119 |

| Odds ratio | P | Odds ratio | P | Odds ratio | P | |

| Self-management | 1.19* | 0.045 | 1.41*** | <0.001 | 1.19* | 0.045 |

| Comprehensiveness | 1.31** | 0.001 | 1.61*** | <0.001 | 1.22* | 0.022 |

*** p<0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05. Scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating better experience of care. Adjusted mean differences and p-values are presented for continuous variables. Note that the adjusted differences may not exactly match the difference between the unadjusted, weighted means in Figure 1a and b. Global odds ratios are presented for ordinal variables

Consistent with the general population results, analyses performed among high-risk patients revealed that MiPCT patients reported significantly better experiences than the non-PCMH group in the same five domains (Table 4, bottom). In addition, group differences are marginally significant for the provider rating measure (p<0.06). Further, the non-participating PCMH patient group showed significantly higher scores than the non-PCMH group on four of the six domains, including access, coordination, self-management support, and comprehensiveness. For all four of these domains, MiPCT patients showed significantly higher adjusted mean scores than the non-participating PCMH patients.

In terms of covariates, payer group was shown to have a significant association with access, communication, coordination, provider rating, and comprehensiveness (with Medicare patients reporting higher ratings and Medicaid patients reporting lower ratings across most domains, but commercial patients reporting better experiences in terms of comprehensiveness). A lower level of education (high school/some college) and Hispanic ethnicity was predictive of lower access among the general population. Smaller practice size was predictive of greater access. Detailed results are presented in the online Appendix.

DISCUSSION

The present study assessed the patient experience among practices in MiPCT—multi-payer PCMH initiative that implemented care management and other advanced practices supported by enhanced payment, training and mentorship, and ongoing learning opportunities—relative to both PCMH and non-PCMH practices that did not participate in the demonstration.

First, the study confirms both of our initial hypotheses: that we would see the greatest differences in patient experience when we compared MiPCT patients and non-PCMH patients, and that we would see a differentiation between MiPCT and non-participating PCMH patients, and between those non-participating PCMH patients and non-PCMH patients. These findings confirm and extend previous reports of improved care experience associated with the PCMH model7 – 12 and may help to explain the equivocal results of previous PCMH evaluations of early or partial implementations.14 , 15

Our results are strengthened by the finding that much of the differentiation among study groups occurred in four domains of patient experience: access, coordination, self-management, and comprehensiveness. Practice capacities relevant to these domains are a major part of the intervention, and/or are specifically related to the PCMH model. For example, MiPCT practices were held to higher standards of access and hired Care Managers specifically charged with care coordination. In addition, self-management support and comprehensiveness are the only domains assessed that specifically came from the CAHPS PCMH item set (rather than the base CG-CAHPS tool).

The study also provides evidence to support the idea that multi-payer advanced PCMH implementation can confer benefits to patients in their experience of care over and above those of non-participating PCMHs. For self-management support and comprehensiveness, MiPCT PCMHs were rated higher than non-participating PCMHs in both populations, and in two additional domains, access and coordination of care, in the high-risk population. The high-risk population presents a major focus of this study, and specifically with regard to these domains, since such patients are more likely than others to seek access, and have more aspects of care that need to be coordinated.

This study addressed potential confounding effects of pre-existing practice-level differences by including both hospital employment and practice size as covariates in the analyses. Small practice size predicted better ratings in the access domain—but this works against our hypothesis, since MiPCT early-adopter practices were more frequently large practices.

LIMITATIONS

The analysis used weighting and covariate controls to minimize non-response bias (see online Appendix for additional information). The study would be stronger if we were able to employ a longitudinal design. This would enable us to better disentangle the relative contributions of having more time for transformation versus the extra resources provided by MiPCT. It would also enable difference-in-difference modeling to compare how both MiPCT and comparison patient experience may have changed over time, while accounting for unmeasured differences between the practices that may have been present at baseline and were unrelated to PCMH adoption. We also recognize that our study may have found statistical significance where the clinical significance is relatively small. Small effect sizes are quite common when working with aggregated patient experience data. Despite this limitation, we noted consistent and statistically significant results between MiPCT and comparison practices across patient experience domains, with an apparent “dose” effect (highest experience scores for MiPCT patients, followed by non-participating PCMH, and then by non-PCMH patients). No other variable had such a consistent relationship with the outcome domains.

The generalizability of our results could be limited by factors specific to Michigan. A recent study reports considerable variation in implementation parameters among multi-payer initiatives, including convener identity, payment methodology, performance measures, and practice participation criteria.20 However, we believe that Michigan’s size and diversity likely make it comparable to many other areas of the country.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that PCMH implementation is sufficient to confer benefits in some domains of patient experience, particularly in the high-risk population. Moreover, a more mature and advanced multi-payer model has an even stronger association with better patient experiences for both high-risk and general populations. At a time when multi-payer PCMH initiatives are taking hold throughout the country, and seem poised to provide platforms to advance larger delivery systems and payment reforms, it is critically important to evaluate the impact of such initiatives on outcomes, including patient experience.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 96 kb)

Acknowledgements

Contributors

The survey was conducted by Morpace, Inc., Farmington Hills, Michigan.

Funders

The MiPCT evaluation is funded by the participating payers in the MiPCT demonstration through an administrative fee charged on a per-member/per-month basis.

Prior presentations

This material has been presented at Michigan stakeholder meetings but has not been presented at any conferences.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home 2007. http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf. Accessed May, 31 2017.

- 2.Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro JL, Parchman ML, Meyers DS. Early evaluations of the medical home: building on a promising start. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:105–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins S, Chawla R, Colombo C, Snyder R, Nigam S. Medical homes and cost and utilization among high-risk patients. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:e61–e71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peikes D, Dale S, Lundquist E, Genevro J, Meyers D. Building the evidence base for the medical home: what sample and sample size do studies need? White Paper. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0100-EF. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.: Rockville, MD; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoff T, Weller W, DePuccio M. The patient-centered medical home: a review of recent research. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:619–44. doi: 10.1177/1077558712447688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettger JP, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, et al. Improving patient care. The patient centered medical home. A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:169–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kern LM, Dhopeshwarkar RV, Edwards A, Kaushal R. Patient experience over time in patient-centered medical homes. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:403–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeng DD, Davis DE, Tomcavage J, Graf TR, Procopio KM. Improving patient experience by transforming primary care: evidence from Geisinger's patient-centered medical homes. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16:157–63. doi: 10.1089/pop.2012.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, Fishman PA, Hsu C, Soman MP, et al. The Group Health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff. 2010;29:835–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid RJ, Fishman PA, Yu O, Ross TR, Tufano JT, Soman MP, et al. Patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:e71–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xin H, Kilgore ML, Sen BP. Is Access to and Use of Primary Care Practices that Patients Perceive as Having Essential Qualities of a Patient-Centered Medical Home Associated With Positive Patient Experience? Empirical Evidence From a U.S. Nationally Representative Sample. J Healthc Qual. 2017;39:4–14. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000462688.01125.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heyworth L, Bitton A, Lipsitz SR, Schilling T, Schiff GD, Bates DW, et al. Patient-centered medical home transformation with payment reform: patient experience outcomes. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aysola J, Werner RM, Keddem S, SoRelle R, Shea JA. Asking the Patient About Patient-Centered Medical Homes: A Qualitative Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1461–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martsolf GR, Alexander JA, Shi Y, Casalino LP, Rittenhouse DR, Scanlon DP, et al. The patient-centered medical home and patient experience. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:2273–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaen CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, Palmer RF, Wood R, Davila M, et al. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home National Demonstration Project. Ann Intern Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S57–67. doi: 10.1370/afm.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy A, Canamucio A, Werner RM. Impact of the patient-centered medical home on veterans' experience of care. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:413–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Fontaine P, Flottemesch TJ, Pawlson LG, Scholle SH. Relationship of clinic medical home scores to quality and patient experience. J Ambul Care Manag. 2011;34:57–66. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ff6faf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Fontaine P, Flottemesch TJ, Anderson LH. Trends in quality during medical home transformation. Ann Intern Med. 2011;9:515–21. doi: 10.1370/afm.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinsler S, Wirth, B. Sustaining Multi-Payer Medical Home Programs: Seven Recommendations for States. NASHP Briefing. Oct. 2014. http://www.nashp.org/sites/default/files/Sustaining-PCMH-Brf2.pdf. Accessed May, 31 2017.

- 20.Takach M, Townley C, Yalowich R, Kinsler S. Making multipayer reform work: what can be learned from medical home initiatives. Health Aff. 2015;34:662–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peikes D, Taylor E, Dale S, O’Malley A, Ghosh A, Anglin G, et al. Evaluation of the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: Second Annual Report. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, April. 2016. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/cpci-evalrpt2.pdf

- 22.Harrington K. Maine Patient Experience Matters: Analysis of Patient Experience Over Time, 2012 and 2014. Maine Quality Forum. http://mainepatientexperiencematters.org/upload/Maine_Patient_Experience_Matters_Analysis_Over_Time_4.4.16.pdf. Accessed May, 31 2017.

- 23.Wholey DR, Finch M, Shippee ND, White KM, Christianson J, Krieger R, et al. Evaluation of the State of Minnesota's Health Care Homes Initiative: Evaluation Report for Years 2010-2014: Minnesota Department of Health. http://www.health.state.mn.us/healthreform/homes/legreport/docs/hch2016report.pdf. Accessed May, 31 2017.

- 24.Alexander JA, Paustian M, Wise CG, Green LA, Fetters MD, Mason M, et al. Assessment and measurement of patient-centered medical home implementation: the BCBSM experience. Ann Intern Med. 2013;11(Suppl 1):S74–81. doi: 10.1370/afm.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annis-Emeott A, Markovitz A, Mason MH, Rajt L, Share DA, Paustian M, et al. Four-year evolution of a large, state-wide patient-centered medical home designation program in Michigan. Med Care. 2013;51(9):846–53. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829fa8c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Principles Underlying CAHPS Surveys. https://cahps.ahrq.gov/about-cahps/Principles/index.html. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- 27.Dyer N, Sorra JS, Smith SA, Cleary PD, Hays RD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS(R)) Clinician and Group Adult Visit Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S28–34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826cbc0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core survey. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1509–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hays RD, Berman LJ, Kanter MH, Hugh M, Oglesby RR, Kim CY, et al. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the CAHPS Patient-centered Medical Home survey. Clin Ther. 2014;36:689–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholle SH, Vuong O, Ding L, Fry S, Gallagher P, Brown JA, et al. Development of and field test results for the CAHPS PCMH Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S2–10. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182610aba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinick RM, Quigley DD, Mayer LA, Sellers CD. Use of CAHPS patient experience surveys to assess the impact of health care innovations. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40:418–27. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(14)40054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McWilliams JM, Landon BE, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM. Changes in patients' experiences in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1715–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 22.0. IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, 2012.

- 34.Bergeson SC, Gray J, Ehrmantraut LA, Laibson T, Hays RD. Comparing Web-based with Mail Survey Administration of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS(R)) Clinician and Group Survey. Prim Health Care. 2013;15:1–7. doi: 10.4172/2167-1079.1000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 96 kb)