Abstract

Objectives

To present our experience of managing penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in a tertiary hospital in Singapore and to evaluate the prognostic value of the inflammatory markers neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR).

Patients and methods

We reviewed our prospectively maintained Institutional Review Board-approved urological cancer database to identify men treated for penile SCC at our centre between January 2007 and December 2015. For all the patients identified, we collected epidemiological and clinical data.

Results

In all, 39 patients were identified who were treated for penile SCC in our centre. The median [interquartile range (IQR)] follow-up was 34 (16.5–66) months. Although very few (23%) of our patients with high-risk clinical node-negative underwent prophylactic inguinal lymph node dissection (ILND), they still had excellent 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS; 90%) and cancer-specific survival (CSS; 90%). At multivariate analysis, higher N stage was significantly associated with worse RFS and CSS. Patients with a high NLR (≥2.8) had significantly higher T-stage (P = 0.006) and worse CSS (P < 0.001) than those with a low NLR. Patients with a low LMR (<3.3) had significantly higher T-stage (P = 0.013) and worse RFS (P = 0.009) and CSS (P < 0.022) than those with a high LMR.

Conclusions

Although very few of our patients with intermediate- and high-risk clinical node-negative SCC underwent prophylactic ILND, they still had excellent 5-year RFS and CSS. However, survival was poor in patients with node-positive disease. The pre-treatment NLR and LMR could serve as biomarkers to predict the prognosis of patients with penile cancer.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CIS, carcinoma in situ; CRP, C-reactive protein; CSS, cancer-specific survival; DSNB, dynamic sentinel node biopsy; EAU, European Association of Urology; HPV, human papillomavirus; ILND, inguinal lymph node dissection; IQR, interquartile range; LMR, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma

Keywords: Inflammatory markers, Inguinal, Lymph node, Penile cancer, Penis

Introduction

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is uncommon in developed nations, including Singapore. In Singapore, the age-standardised incidence rate for penile cancer between 2003 and 2007 was 0.94 per 100,000 person years [1]. This means that penile cancer only accounted for ∼0.4% of all cancers in males in Singapore. Despite the low incidence, penile cancer is often aggressive and treatment usually results in significant morbidity, including its impact on the psychology and sexuality of patients. Risk factors for the development of penile SCC include phimosis, tobacco use, balanitis, chronic inflammation, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection [2].

In addition to the management of the primary penile SCC, both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [3] and the European Association of Urology (EAU) [4] clinical practice guidelines emphasise that the management of the regional lymph nodes is decisive for long-term survival of the patient. Both guidelines subdivide patients with clinically normal lymph nodes (cN0) into low-risk (Tis, Ta and pT1a), intermediate-risk (pT1b, Grade 1 or 2) or high-risk (pT1b, Grade 3 or 4; any pT2 or greater) groups. Patients with low-risk SCC can be managed by surveillance, but both guidelines recommend invasive nodal staging with either bilateral modified inguinal lymph node dissection (ILND) or dynamic sentinel node biopsy (DSNB) in patients with intermediate- or high-risk disease. The reason for this recommendation is that early ILND in patients with clinically node-negative penile SCC results in far superior long-term survival compared to therapeutic lymphadenectomy when regional nodal recurrence has occurred [5].

However, ILND is associated with high rates of postoperative complications [6]. In patients with clinically negative inguinal lymph nodes but considered at intermediate-risk, only up to 30% of them will harbour micro-metastatic disease after ILND. This means that up to 70% of these patients will go through ILND with no clinical benefit. To better select patients for ILND, various groups have investigated the prognostic role of biomarkers. Biomarkers purported to be associated with lymph node metastasis include: tissue markers, e.g. overexpression of p53 and Ki-67, and loss of membranous E-cadherin in biopsy or penectomy tissue specimens. However, these tissue markers are of limited use in clinical practice as the standard threshold of positivity is not well defined [7].

Due to the link between cancer development and systemic inflammation [8], more recent reports have evaluated the prognostic role of serum inflammatory markers. Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) has been reported to be associated with nodal metastasis and poorer cancer-specific survival (CSS) [9], [10], and a high neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has also been shown to predict poor CSS in patients with penile cancer [11]. Another potential biomarker, the absolute lymphocyte count–absolute monocyte count ratio (LMR) has been shown to be able to predict clinical outcomes of patients with cancer, including colorectal cancer, sarcoma and lymphoid neoplasms [12], [13], [14]. However, there has been no study evaluating its role in providing prognostic information in patients with penile cancer.

In the present study, we present our experience of managing penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in a tertiary hospital in Singapore and evaluate the prognostic value of the inflammatory markers NLR and lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR).

Patients and methods

We reviewed our prospectively maintained Institutional Review Board-approved urological cancer database to identify men treated for penile SCC at our centre between January 2007 and December 2015. Epidemiological and clinical data, including age, smoking history, circumcision status, body mass index (BMI), preoperative full blood count results, TNM staging, tumour pathology, treatment history and oncological outcome, were collected for all patients. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method for univariate analysis and Cox regression for multivariate analysis.

Results

In all, 39 patients were identified who were treated for penile SCC in our centre. The median [interquartile range (IQR)] age was 65.1 (59–72.5) years and the median (IQR) BMI was 25.6 (22.7–27.6). In all, 61.5% of the patients had risk factors, which included previous carcinoma in situ (CIS; 10.3%), smoking (43.6%), and phimosis (25.6%). Only three (7.7%) patients had had previous circumcision (Table 1). In all, 29 patients (74.4%) had their penile tumour located at the glans penis and/or prepuce, and 10 (25.6%) had their tumour located along the penile shaft. The median (range) tumour size was 3 (1–9) cm. For primary treatment, 30.8% had an excisional biopsy, 25.6% underwent partial penectomy, 38.5% had total penectomy, and 5.1% underwent radiotherapy (Table 1). The median (IQR) follow-up was 34 (16.5–66) months.

Table 1.

The patients’ demographics.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean (IQR) | |

| Age, years | 65.1 (59–72.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.6 (22.7–27.6) |

| N (%) | |

| Previous circumcision | |

| Yes | 3 (7.7) |

| No | 36 (92.3) |

| Smoker | |

| Yes | 17 (43.6) |

| No | 19 (48.7) |

| Not documented | 3 (7.7) |

| Location of penile tumour | |

| Glans penis and/or prepuce | 29 (74.4) |

| Penile shaft | 10 (25.6) |

| Primary treatment of penile tumour | |

| Excisional biopsy | 12 (30.8) |

| Partial penectomy | 10 (25.6) |

| Total penectomy | 15 (38.5) |

| Radiation therapy | 2 (5.1) |

| T Stage | |

| CIS | 7 (17.9) |

| Ta | 1 (2.6) |

| T1a | 11 (28.2) |

| T1b | 1 (2.6) |

| T2 | 14 (35.9) |

| T3 | 5 (12.8) |

| Clinical node status at presentation | |

| Clinically node negative | 31 (79.5) |

| Clinically node positive | 8 (20.5) |

| N Stage | |

| N0 | 31 (79.5) |

| N1 | 3 (7.7) |

| N2 | 2 (5.1) |

| N3 | 3 (7.7) |

| Grade | |

| CIS | 7 (17.9) |

| G1 | 8 (20.5) |

| G2 | 17 (43.6) |

| G3 | 7 (17.9) |

| Pathological stage | |

| 0 | 8 (20.5) |

| 1 | 10 (25.6) |

| 2 | 13 (33.3) |

| 3 | 5 (12.8) |

| 4 | 3 (7.7) |

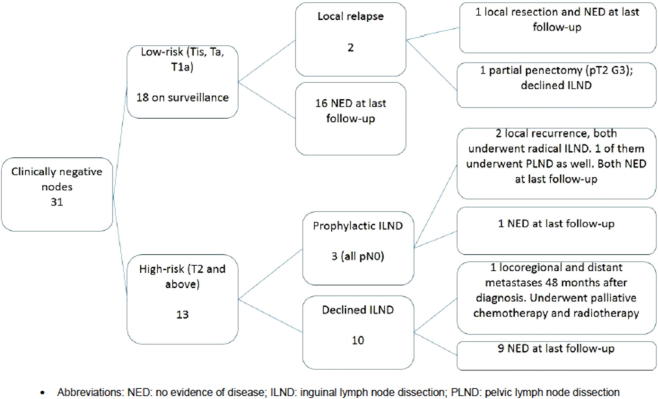

In our study, 13 patients had clinically node-negative disease but were classified as having high-risk disease (none of the patients in our study had intermediate-risk disease). Based on the NCCN and EAU guidelines as stated above, they should have undergone invasive nodal staging. However, only three of these 13 high-risk clinically node-negative patients underwent staging ILND, with no pathological lymph node metastasis detected in any of them. One of them developed a local inguinal lymph node recurrence after 15 months, but none of them had died after a mean follow-up of 33 months. For the 10 men with no ILND performed, after a mean follow-up of 61 months, both the recurrence-free survival (RFS) and CSS were 90% (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Management of patients with clinically negative lymph nodes. NED, no evidence of disease; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection.

In the eight patients with palpable inguinal lymph nodes, six underwent radical ILND (with one undergoing pelvic LND as well) and all had pN1–pN3 disease. After a mean follow-up of 43 months, four had disease recurrence and two of them died from penile cancer. Of the two patients who did not undergo ILND, one had rapidly progressive disease and died after 3 months; the other patient defaulted follow-up and subsequently re-presented with metastatic disease and died 35 months after diagnosis.

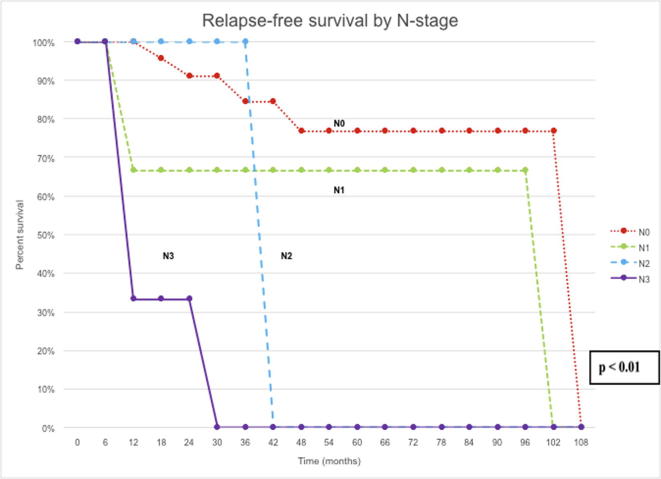

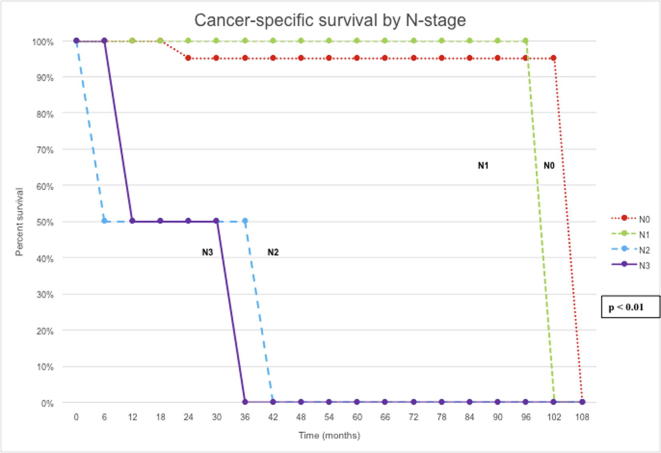

At the univariate level, RFS was significantly correlated with pathological stage (P < 0.01), lymph node status (P < 0.01) and whether an ILND was performed (P < 0.01). CSS was significantly correlated with pathological stage (P < 0.01), grade of disease (P = 0.02), lymph node status (P < 0.01), type of local treatment (P < 0.01), and history of disease relapse (P = 0.04) (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

RFS by N stage.

Figure 3.

CSS by N stage.

However, at multivariate analysis, only lymph node status (P = 0.03) remained significant for RFS and CSS (P < 0.01).

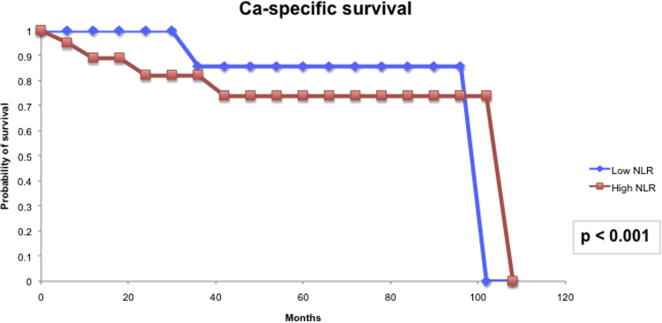

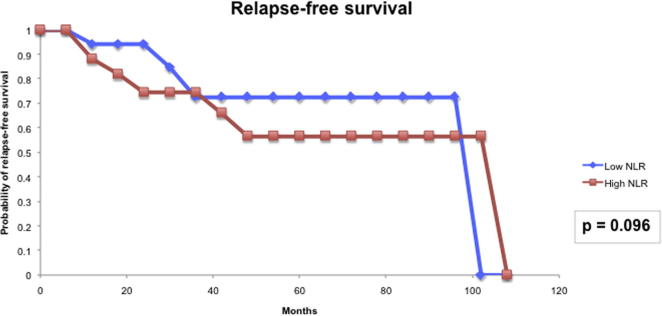

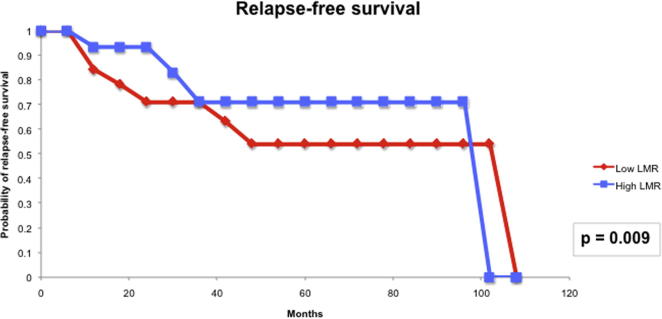

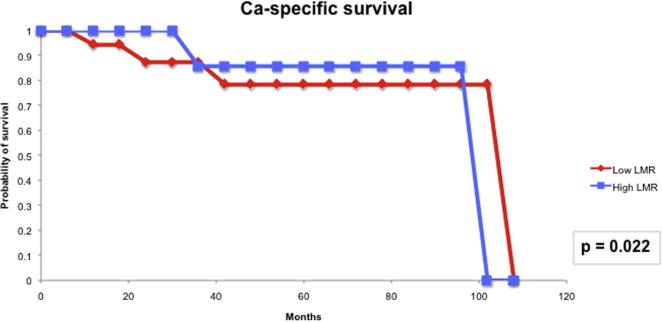

For the prognostic role of inflammatory markers, we assessed the utility of pre-treatment NLR and LMR in our cohort of patients. The median (IQR) NLR was 2.99 (0.76–5.22) and the median (IQR) LMR was 3.12 (1.82–4.41). Based on the area under the receiver operator characteristic curve, the threshold value of NLR was determined to be 2.8 and that of LMR was 3.3. Patients with a high NLR (≥2.8) had significantly higher T-stage (P = 0.006) and worse CSS (P < 0.001) than those with a low NLR (Fig. 4). However, high NLR was not significantly associated with RFS (Fig. 5). Patients with a low LMR (<3.3) had significantly higher T-stage (P = 0.013) and worse RFS (P = 0.009) and CSS (P < 0.022) than those with a high LMR (Figure 6, Figure 7).

Figure 4.

NLR and CSS.

Figure 5.

NLR and RFS.

Figure 6.

LMR and RFS.

Figure 7.

LMR and CSS.

Discussion

Penile SCC is rare in Singapore. Our present report, which represents the largest published penile cancer experience from a tertiary hospital in Singapore, consisted of 39 patients diagnosed and treated over a period of 9 years. Most (61.5%) of our patients had known risk factors for penile SCC, such as smoking, phimosis, and previous CIS of the penis [2], [15].

The management of the regional lymph nodes in penile cancer is important for long-term patient survival. For patients with clinically node-negative disease, risk stratification depends on stage, grade and the presence of lymphovascular invasion in the primary tumour [16]. Imaging techniques (e.g. ultrasonography, CT and MRI) are unreliable in excluding small and micro-metastatic lymph node involvement and thus staging of the inguinal lymph nodes in clinically node-negative disease requires an invasive procedure. There are currently only two invasive diagnostic procedures for staging the inguinal lymph nodes, which are evidence-based: ILND or DSNB. ILND is the standard surgical approach where the superficial inguinal lymph nodes from at least the central and both superior Daseler’s zones are removed bilaterally, leaving behind the great saphenous vein [17]. DSNB is based on the concept that lymphatic drainage in penile cancer initially goes to one or a few sentinel inguinal nodes on each side before further dissemination of disease. Technetium-99m nanocolloid is injected around the penile cancer site on the day before surgery. A blue dye can be injected as well. A γ-ray detection probe is then used intraoperatively to detect the sentinel node. The sensitivity of DSNB in recent series have consistently been reported to be >90% [18], [19]. Unfortunately, DSNB for penile cancer is not available in Singapore. If lymph node metastasis is found with either ILND or DSNB, an ipsilateral radical ILND is indicated.

The NCCN and EAU guidelines both subdivide patients with clinically normal lymph nodes into low-risk (Tis, Ta and pT1a), intermediate-risk (pT1b, Grade 1 or 2) or high-risk (pT1b, Grade 3 or 4; any pT2 or greater) groups. Patients with low-risk disease can be managed by surveillance, but both guidelines recommend invasive nodal staging with either ILND or DSNB in patients with intermediate- or high-risk disease. The reason for this recommendation is that early ILND in patients with clinically node-negative disease results in far superior long-term survival compared to therapeutic ILND when regional nodal recurrence has occurred [5]. In a retrospective Dutch series of 40 patients with T2–3 penile carcinoma and bilateral impalpable inguinal lymph nodes, Kroon et al. [5] reported an improved 3-year disease-specific survival of 84% for early ILND compared to 35% for those who had positive lymph nodes detected during surveillance (P = 0.002).

Despite the NCCN and EAU guidelines advocating invasive nodal staging for high-risk clinical node-negative disease, we found that compliance to the guidelines was poor in our present study, with only three of 13 ‘at-risk’ patients undergoing ILND. Surprisingly, after a mean follow-up of 61 months, only one of the 10 men who did not undergo prophylactic ILND developed a recurrence (he subsequently died from the disease), thus giving a 5-year RFS of 90% and 5-year CSS of 90% in these patients. This finding may be due to the small size of our present study but we do not exclude the possibility that the risk of lymph node metastasis in our patients may be lower. Certainly, further studies are required to refine the selection criteria for prophylactic ILND in our patients.

Our present study also highlighted the dismal prognosis for patients with pathological lymph node metastases. Of the eight patients with palpable inguinal lymph nodes, four died from the disease during a mean follow-up of 43 months.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were completed to identify prognostic factors for penile SCC. Nodal metastasis was the only risk factor that was significantly associated with worse RFS and CSS.

Our present study also evaluated the utility of inflammatory markers in determining the prognosis for patients with penile cancer. The link between cancer development and inflammation is generally accepted, with tumours often presenting with characteristics of inflamed tissues, such as immune cell infiltration and an activated stroma [8]. It is thought that inflammation not only generates cancer-promoting micro-environmental changes, but also systemic changes that are favourable for cancer progression. The systemic inflammatory response that is usually measured by surrogate peripheral blood-based variables, including neutrophil, platelet count and CRP, has been shown to independently predict the clinical outcome of various human cancers [20]. Of these inflammatory markers, elevated CRP has been reported to be associated with nodal metastasis and poorer CSS [9], [10], and a high NLR has also been shown to predict poor CSS in patients with penile cancer [11]. As most of the patients in our present study did not have their serum CRP levels measured preoperatively, we were unable to evaluate this variable in our cohort. NLR was shown to be useful in our present cohort in terms of predicting T-stage and CSS. LMR, which has not been evaluated before in patients with penile cancer, had previously been shown to be able to predict clinical outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer, sarcoma and lymphoid neoplasms [12], [13], [14]. In our present study, patients with a low LMR (<3.3) had a significantly higher T-stage (P = 0.013) and worse RFS (P = 0.009) and CSS (P < 0.022) than those with a high LMR. Thus, from the findings of our present study, the inflammatory biomarkers, NLR and LMR, could serve as biomarkers to predict the prognosis of patients with penile cancer.

We acknowledge the retrospective nature of our study and our small sample size as key weaknesses of our present study. However, in view of our unexpected finding of the very low incidence of metastatic disease in our high-risk clinical node-negative group of patients, we will work together with our local and regional counterparts to expand our database of patients with penile SCC to enable us to further refine the selection criteria for prophylactic ILND in our patients.

In conclusion, we present the largest published penile cancer experience from a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Risk factors for penile SCC, including smoking, phimosis and previous CIS of the penis, were found in most of our patients. Interestingly, our present study found that although very few (three of 13) of our high-risk clinical node-negative patients underwent prophylactic ILND they still had excellent 5-year RFS and CSS (both 90%). However, in patients with palpable and/or pathological lymph nodes, our present findings confirm the poor survival of these patients. Finally, the inflammatory biomarkers, NLR and LMR, may serve as biomarkers to predict the prognosis of patients with penile cancer.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interests to declare.

Oncology/Reconstruction

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health Singapore, National Registry of Diseases Office. Cancer incidence and mortality 2003-2012 and selected trends 1973-2012 in Singapore. Singapore Cancer Registry Report No. 8, 2016. Available at: https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/publications/cancer. Accessed March 2017.

- 2.Pow-Sang M.R., Ferreira U., Pow-Sang J.M., Nardi A.C., Destefano V. Epidemiology and natural history of penile cancer. Urology. 2010;76:S2–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Penile Cancer (Version 1.2016). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; 2016. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines_nojava.asp. Accessed March 2017.

- 4.Hakenberg O.W., Compérat E.M., Minhas S., Necchi A., Protzel C., Watkin EAU guidelines on penile cancer. 2014 Update. Eur Urol. 2015;67:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroon B.K., Horenblas S., Lont A.P., Tanis P.J., Gallee M.P., Nieweg O.E. Patients with penile carcinoma benefit from immediate resection of clinically occult lymph node metastases. J Urol. 2005;173:816–819. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154565.37397.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevan-Thomas R., Slaton J.W., Pettaway C.A. Contemporary morbidity from lymphadenectomy for penile squamous cell carcinoma: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Experience. J Urol. 2002;167:1638–1642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Y., Zhou X.Y., Yao X.D., Dai B., Ye D.W. The prognostic significance of p53, Ki-67, epithelial cadherin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in penile squamous cell carcinoma treated with surgery. BJU Int. 2007;100:204–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chechlinska M. Systemic inflammation as a confounding factor in cancer biomarker discovery and validation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:2–3. doi: 10.1038/nrc2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Ghazal A., Steffens S., Steinestel J., Lehmann R., Schnoeller T.J., Schulte-Hostede A. Elevated C-reactive protein values predict nodal metastasis in patients with penile cancer. BMC Urol. 2013;13:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-13-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steffens S., Al Ghazal A., Steinestel J., Lehmann R., Wegener G., Schnoeller T.J. High CRP values predict poor survival in patients with penile cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:223. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasuga J., Kawahara T., Takamoto D., Fukui S., Tokita T., Tadenuma T. Increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with disease-specific mortality in patients with penile cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:396. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2443-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stotz M., Pichler M., Absenger G., Szkandera J., Arminger F., Schaberl-Moser R. The preoperative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in patients with stage III colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:435–440. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szkandera J., Gerger A., Liegl-Atzwanger B., Absenger G., Stotz M., Friesenbichler J. The lymphocyte/monocyte ratio predicts poor clinical outcome and improves the predictive accuracy in patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:362–370. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steidl C., Lee T., Shah S.P., Farinha P., Han G., Nayar T. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bleeker M.C., Heideman Da, Snijders P.J. Penile cancer: epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention. World J Urol. 2009;27:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0302-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philippou P., Shabbir M., Malone P., Nigam R., Muneer A., Ralph D.J. Conservative surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: resection margins and long-term oncological control. J Urol. 2012;188:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao K., Tu H., Li Y.H., Qin Z.K., Liu Z.W., Zhou F.J. Modified technique of radical inguinal lymphadenectomy for penile carcinoma: morbidity and outcome. J Urol. 2010;184:546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam W., Alnajjar H.M., La-Touche S., Perry M., Sharma D., Corbishley C. Dynamic sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: a prospective study of the long-term outcome of 500 inguinal basins assessed at a single institution. Eur Urol. 2013;63:657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kathiresan N., Raja K., Ramachandran K.K., Sundersingh S. Role of dynamic sentinel node biopsy in carcinoma penis with or without palpable nodes. Indian J Urol. 2016;32:57–60. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.173111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roxburgh C.S., McMillan D.C. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:149–163. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]