Abstract

Coral calcification is dependent on both the supply of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and the up-regulation of pH in the calcifying fluid (cf). Using geochemical proxies (δ11B, B/Ca, Sr/Ca, Li/Mg), we show seasonal changes in the pHcf and DICcf for Acropora yongei and Pocillopora damicornis growing in-situ at Rottnest Island (32°S) in Western Australia. Changes in pHcf range from 8.38 in summer to 8.60 in winter, while DICcf is 25 to 30% higher during summer compared to winter (×1.5 to ×2 seawater). Thus, both variables are up-regulated well above seawater values and are seasonally out of phase with one another. The net effect of this counter-cyclical behaviour between DICcf and pHcf is that the aragonite saturation state of the calcifying fluid (Ωcf) is elevated ~4 times above seawater values and is ~25 to 40% higher during winter compared to summer. Thus, these corals control the chemical composition of the calcifying fluid to help sustain near-constant year-round calcification rates, despite a seasonal seawater temperature range from just ~19° to 24 °C. The ability of corals to up-regulate Ωcf is a key mechanism to optimise biomineralization, and is thus critical for the future of coral calcification under high CO2 conditions.

Introduction

Coral reefs face an uncertain future due to increasing seawater temperatures and ocean acidification resulting from CO2-driven climate change1,2. Rising ocean temperatures are expected to lead to more frequent mass coral bleaching events, defined as a loss of the endosymbiotic dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae) from the coral host3–5. While corals have demonstrated the capacity to adapt to long-term changes in climate, they are still extremely vulnerable to abrupt warming events (i.e., weeks to months) as evident, for example, by the mass bleaching events that often follow El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) driven warming events6,7. Additionally, evidence suggests8–10 that declining seawater pH will cause the growth rates of important marine calcifiers, such as hermatypic corals, to slow down. The effect of declining pH on the calcification process is however still in question, as corals possess the physiological mechanisms to partially resist or limit the effects of ocean acidification on the bio-calcification process11–16. They accomplish this through the up-regulation of the pH of the calcifying fluid (pHcf); a process that likely occurs via active ionic exchange of Ca2+ with H+ via Ca-ATPase17,18 ‘pumps’ at the site of calcification11–16. This in turn helps to elevate the aragonite saturation state in the calcifying fluid (Ωcf), a key requirement for the formation of their calcium carbonate (CaCO3) skeletons11–16,19,20. In addition to up-regulating pHcf, corals supply the calcifying fluid with metabolically generated dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC)18. This raises the activity of carbonate ions within the calcifying fluid ([CO3 2−]cf) and, therefore, increases Ωcf 21. Thus, corals manipulate rates of aragonite precipitation by actively elevating both pHcf and DICcf 21.

Despite the importance of internal carbonate chemistry in determining rates of mineral precipitation, temperature is still the main factor influencing the rates of coral growth22–24. This is due to both the strong temperature-dependent rate kinetics of aragonite precipitation25 as well as the sensitivity of coral physiology to extremes in temperature6,26. For example, calcification rates in tropical corals are generally thought to follow a Gaussian–shaped curve whereby calcification increases as temperature increases until an optimum is reached; after this maximum, rates decline with increasing temperature7,24,27. Light is also an important driver of coral calcification on both diurnal and seasonal timescales, with rates of carbon fixation by the zooxanthellae symbiont being light dependent18,28,29. Therefore, it is not surprising that higher rates of coral calcification are generally found in summer compared to winter24,30–35. These findings24,30–35 are consistent with the assumption that during the summer there are higher rates of metabolically-derived carbon supply to the coral18 and enhanced temperature-driven precipitation kinetics25.

A recent study by Ross et al.36, however, found that calcification rates for the reef-building species Acropora yongei and Pocillopora damicornis growing offshore Western Australia (Rottnest Island, 32°S) exhibited minimal seasonality and, in fact, exhibited similar or even higher rates in winter. The authors suggested that this uncharacteristic seasonal pattern in calcification rates was due to increased nutrient uptake in winter36–38 and/or a possible sub-lethal stress response in summer36,39. Another possibility, which is explored herein, is that corals physiologically manipulate the chemistry of their calcifying fluid to enhance rates of calcification. Earlier studies have demonstrated that the biological mediation of pH up-regulation can modulate rates of calcification11,13,14,16. However, our ability to infer both aspects of the carbonate chemistry (i.e., pH and DIC) under in-situ conditions has only recently become possible via measuring the boron isotopic composition (δ11B)40–42 and elemental abundance of boron (B/Ca)43 in coral skeletons. Furthermore, while other methods of interrogating the carbonate chemistry of the calcifying fluid have been developed and provide some informative results14,15,19,28,44, they generally must be conducted under tightly constrained laboratory conditions that differ greatly from the in-situ ‘natural’ reef habitats in which corals grow. Nonetheless, previous studies have shown that estimates of internal coral pHcf derived from geochemical tracers12,13,40,45 are consistent with more direct measurements14,19,44, affirming that boron isotopes are providing unbiased measurements of pH at the site of calcification. With these new developments12,21,40,45, we can now determine how the carbonate chemistry of the calcifying fluid (pHcf, DICcf, Ωcf) responds to natural and seasonally varying changes in light, temperature and seawater pH. We show that quantifying these relationships is critical to understanding and predicting how coral growth will respond to man-made climate change under real-world conditions.

Here we examine seasonal changes in the carbonate chemistry of the calcifying fluid (pHcf, DICcf, and Ωcf) for branching corals, Acropora yongei and Pocillopora damicornis, sampled every 1 to 2 months for three summers and two winters in Salmon Bay, Rottnest Island (32°S), Western Australia (WA). Boron isotopic compositions (δ11B) are used as a proxy for pHcf and are combined with skeletal B/Ca ratios to determine [CO3 2−]cf, and hence DICcf. We show that corals in this sub-tropical environment seasonally elevate Ωcf to levels that are ~4 times higher than ambient seawater and ~25% higher in winter compared to summer. We also find enhanced rates of skeletal precipitation relative to that expected from inorganic rate kinetics25; thus emphasizing the ability of corals to manipulate their internal carbonate chemistry to promote biomineralization.

Results

Coral habitat

Monthly average water temperatures at Salmon Bay ranged from 19.3° to 23.7 °C during this study period, giving a seasonal range of 4.4 °C (Supplementary Fig. S1). Monthly mean light levels increased from a minimum of just 15 mol m−2 d−1 in winter to a maximum of 48 mol m−2 d−1 in summer (Supplementary Table S1). Weekly average measured seawater pHT at Rottnest Island showed minimal variability (<0.05 pH units) between summer (January 2014) and winter (July 2014; see Supplementary Fig. S2). The definitions for all physical and biogeochemical variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nomenclature. Definition of variables used in this paper.

| Variable | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|

| δ11B | ‰ | Boron isotope |

| pHcf | — | pH of the calcifying fluid |

| pHT | — | pH on the total hydrogen ion scale |

| pHsw | — | pH of the seawater |

| DICcf | µmol kg−1 | Dissolved inorganic carbon in the calcifying fluid |

| DICsw | µmol kg−1 | Dissolved inorganic carbon in the seawater |

| Ωcf | — | Aragonite saturation state of the calcifying fluid |

| Ωsw | — | Aragonite saturation state of the seawater |

| T | °C | Temperature |

| B/Ca | mmol mol−1 | Boron to calcium ratio |

| Li/Mg | mmol mol−1 | Lithium to magnesium ratio |

| Sr/Ca | mmol mol−1 | Strontium to calcium ratio |

Internal skeletal carbonate chemistry

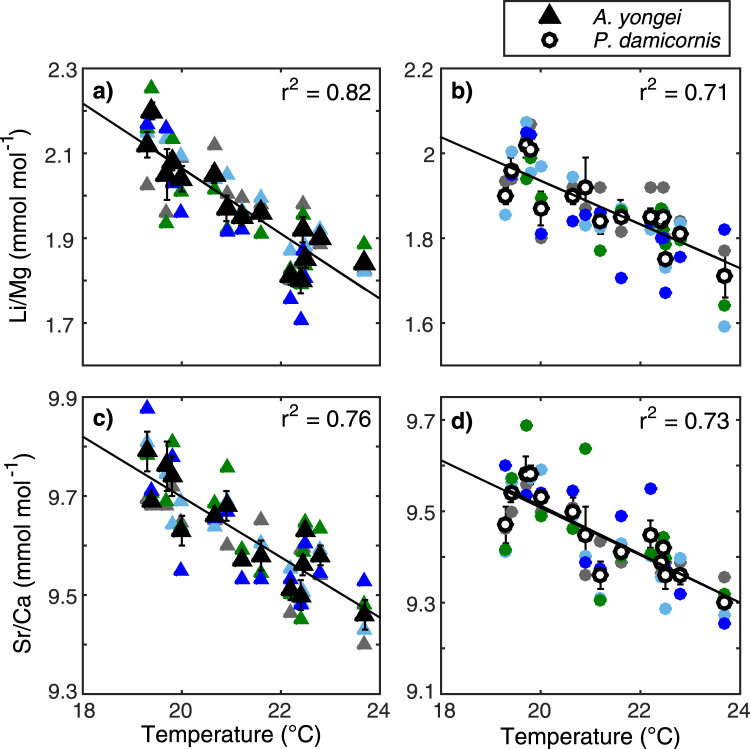

Coral skeletal Li/Mg and Sr/Ca ratios show significant inverse relationships with seasonal increases in temperature for both A. yongei (r 2 = 0.82, r 2 = 0.76, respectively, p < 0.001 for both; Fig. 1) and for P. damicornis (r 2 = 0.71, r 2 = 0.73, respectively, p < 0.001 for both; Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S2). Thus, the geochemical composition of the apical section of the coral skeleton analysed confirms that coral skeletal growth was the same time as when ambient seawater chemistry was measured. This excellent agreement is further supported by earlier measurements36 showing that these coral colonies grew ~4 mm month−1.

Figure 1.

Measured Li/Mg and Sr/Ca in corals at Rottnest Island plotted against seawater temperature. (a,b) Li/Mg plotted against temperature with regression equation Li/Mg = −0.08Tsw + 3.63 for Acropora yongei and Li/Mg = −0.05Tsw + 2.99 for Pocillopora damicornis (c,d) Sr/Ca plotted against temperature with regression equation Sr/Ca = −0.061Tsw + 10.92 for Acropora yongei, and Sr/Ca = −0.053Tsw + 10.57 for Pocillopora damicornis. Coloured symbols represent each colony while the black symbols with lines denote the mean (±1 SE; n = 4) for each time point.

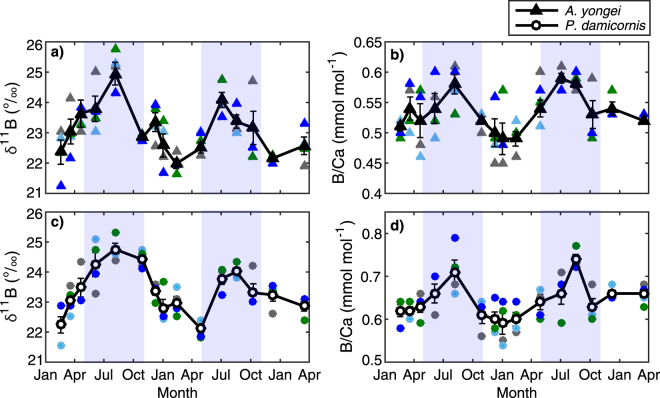

Seasonal δ11B varies by up to 2.7‰ between the warmest month (23.7 °C) and the coolest month (19.3 °C), ranging from a minimum of 22.0‰ in February for both species to a maximum of 24.9‰ in August for A. yongei and 24.8‰ for P. damicornis (Fig. 2a,b; Supplementary Table S2). These ranges in δ11B correspond to seasonal variations in derived pHcf of 8.38 (summer) to 8.60 (winter) for both A. yongei and P. damicornis (Fig. 3) with a lower ΔpHcf of 0.28 (ΔpHcf = pHcf − pHsw) corresponding to warmer seawater temperatures and a higher ΔpHcf of 0.50 corresponding to cooler seawater temperatures (Fig. 3). Skeletal ratios of boron to calcium (B/Ca) range from 0.49 to 0.59 mmol mol−1 for A. yongei and 0.59 to 0.74 mmol mol−1 for P. damicornis (Fig. 2c,d; Supplementary Table S2). These B/Ca ratios correspond to carbonate ion concentrations within the calcifying fluid [CO3 2−]cf of from 806 to 973 µmol kg−1 for A. yongei, and 645 to 886 µmol kg−1 for P. damicornis (Supplementary Table S3) and are ~20 to 40% higher at their peak in winter compared to their low in summer. These values fall within the range of other tropical corals as reported using carbonate-sensitive microelectrodes under laboratory conditions (600 to 1550 µmol kg−1)44.

Figure 2.

Seasonal changes in the boron isotopic signature and boron to calcium ratio (B/Ca) of corals at Rottnest Island. (a,b) Seasonal time-series of δ11B (‰) and (c,d) boron to calcium ratios (B/Ca) for all four colonies sampled of Acropora yongei and Pocillopora damicornis. Coloured symbols represent each colony while the black symbols with lines denote the mean ± 1 SE (n = 4) for each time point. Light blue shading denotes winter and unshaded areas denote summer, defined based on seasonal changes in temperature and light.

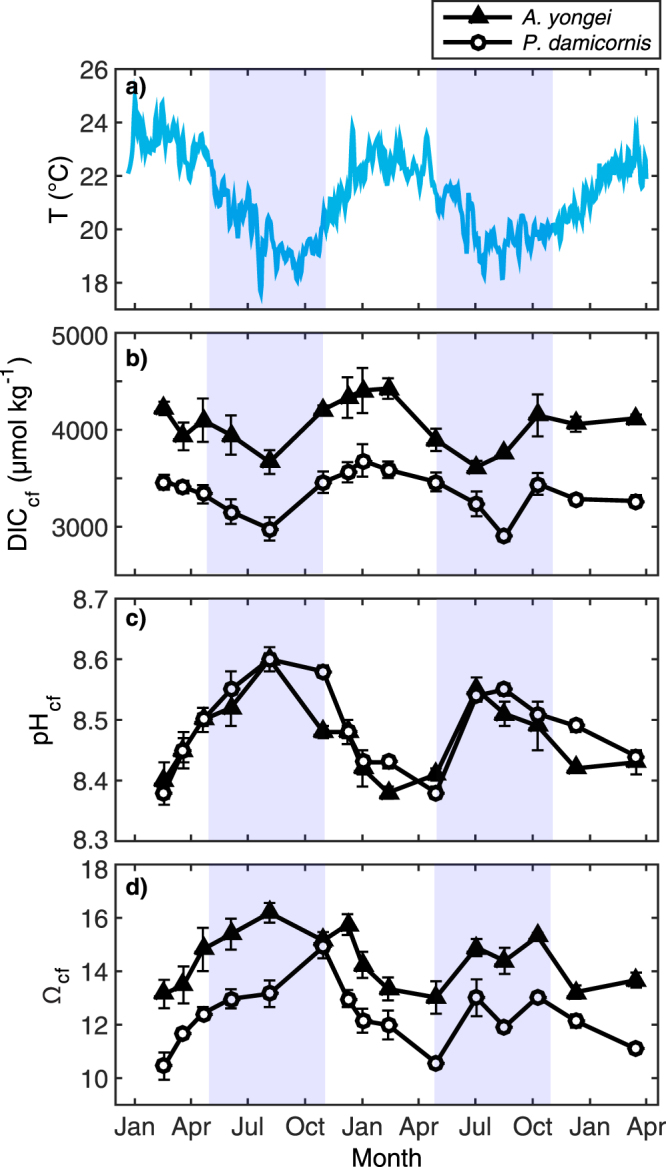

Figure 3.

Time-series of seasonal changes in seawater temperature and calcifying fluid parameters (DICcf, pHcf, Ωcf). (a) Seawater temperature (b) pHcf, (c) predicted dissolved inorganic carbon (DICcf), and (d) Ωcf for coral the species Acropora yongei and Pocillopora damicornis averaged (±1 SE) over each growth period. Light blue shading denotes winter and unshaded areas denote summer, defined based on seasonal changes in temperature and light.

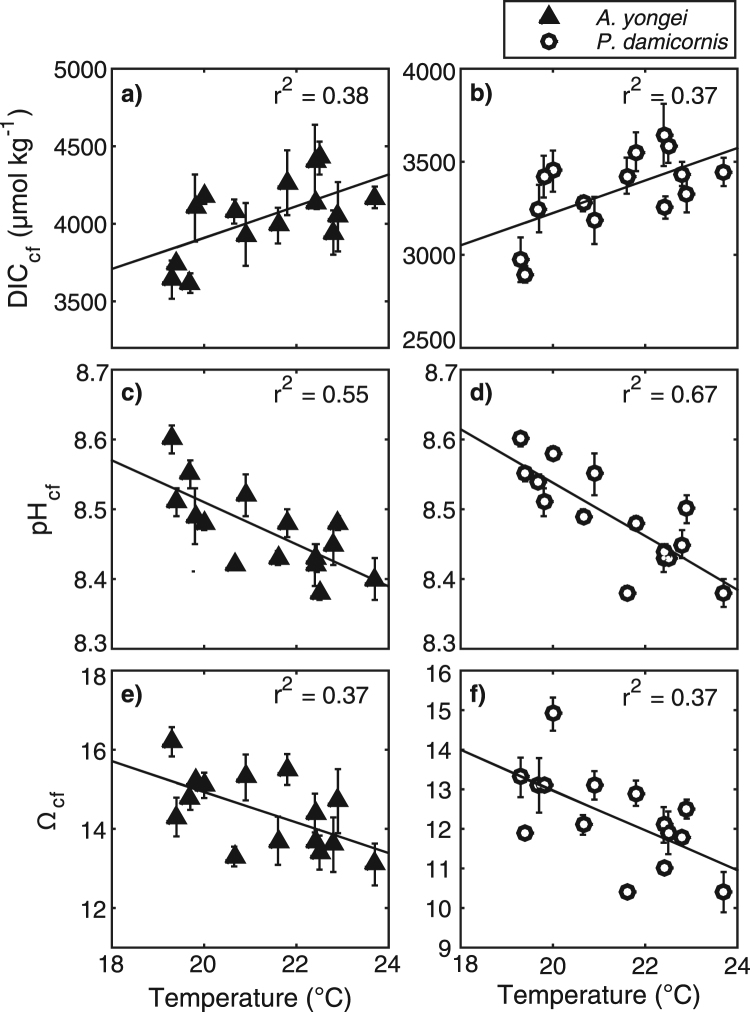

The DICcf derived from the B/Ca ratio proxy is 1.5 to 2 times higher than ambient seawater and is positively correlated with seasonal changes in seawater temperature (r 2 = 0.38, p = 0.015 for A. yongei and r 2 = 0.37, p = 0.017 for P. damicornis; Fig. 4). The DICcf in both coral species is also 25 to 30% higher in summer compared to winter (4520 µmol kg−1 in summer vs. 3620 µmol kg−1 in winter for A. yongei and 3700 µmol kg−1 in summer vs. ~2900 µmol kg−1 in winter for P. damicornis; Fig. 3b). There is a counter-cyclical relationship between DICcf and pHcf such that seasonal changes in DICcf are negatively correlated with seasonal changes in pHcf (r 2 = 0.64, p = 0.002 for A. yongei and r 2 = 0.39, p = 0.01 for P. damicornis; Supplementary Fig. S3). As a result of this inverse relationship between DICcf and pHcf, the highest Ωcf occurs in winter (16.2 for A. yongei and 14.9 for P. damicornis; Fig. 3d) and lowest in summer (13.0 for A. yongei and 10.4 for P. damicornis; Fig. 3d). Thus, Ωcf is negatively correlated with seasonal changes in temperature (r 2 = 0.37, p = 0.015 and r 2 = 0.37, p = 0.02 for A. yongei and P. damicornis, respectively; Fig. 4). Due to the up-regulation of both DICcf and pHcf, Ωcf is roughly 3.5 to 5 times higher than the mean annual seawater aragonite saturation state (Ωsw ≈ 3.2) depending on taxa and season.

Figure 4.

Relationships between calcifying fluid parameters versus seawater temperature. (a,b) Seasonal changes in DICcf, (c,d) pHcf, and (e,f) Ωcf with seawater temperatures for Acropora yongei and Pocillopora damicornis averaged (±1 SE) over each growth period.

Coral growth rates

Results from Ross et al.36 demonstrated that calcification rates generally deviated from their long-term (>1 year) average growth rates of 1.6 mg cm−2 d−1 for A. yongei and 0.67 mg cm−2 d−1 for P. damicornis by just ± 20% to ± 30% over the 18-month period, respectively (Table 2)36. These calcification rates were either negatively correlated with temperature for P. damicornis (r 2 = 0.45) or showed little or no seasonal coherency for A. yongei (i.e., no correlation with temperature r 2 = 0.015)36. Thus, calcification rates exhibited unexpected seasonal patterns whereby they were, on average, similar across seasons for A. yongei, and slighly higher in winter compared to summer for P. damicornis.

Table 2.

Coral calcification rates at Rottnest Island. Seasonal changes in rates of calcification (mg cm−2 d−1; mean ± SE) for coral species (a) Acropora yongei, and (b) Pocillopora damicornis 36. Italic denotes winter and roman areas denote summer.

| Species | Summer 2013 | Winter 2013 | Summer 2014 | Winter 2014 | Ref | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb | Mar | Apr | Jun | Aug | Oct | Dec | Jan | Feb | Apr | ||

| Acropora yongei | 1.54 ± 0.28 | 1.46 ± 0.15 | 2.02 ± 0.14 | 1.76 ± 0.12 | 1.61 ± 0.05 | 1.66 ± 0.07 | 1.79 ± 0.07 | 1.67 ± 0.06 | 1.33 ± 0.09 | 1.25 ± 0.03 | 36 |

| Pocillopora damicornis | 0.60 ± 0.12 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.84 ± 0.10 | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 0.79 ± 0.11 | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 0.81 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 36 |

Discussion

Here we show that corals living in a sub-tropical environment have the ability to modulate rates of calcification by seasonally counter-regulating pHcf and DICcf to elevate Ωcf. The ability to infer coral pHcf from δ11B isotopic measurements is supported by measurements from microelectrodes19,28 and pH-sensitive dyes13,14,46. For example, previous studies13,14 have shown that pHcf up-regulation is ~0.6 to 2 units above seawater values in the light. Results from δ11B-derived pHcf generally fall within this range and are broadly consistent46 with these measurements (~0.3 to 0.6 pH units above seawater)11–13,16,20, given that they are integrated over multiple weeks of biomineralization. Additional variability between methods (i.e., geochemical proxies and direct measurements) may also result from the different species used and the conditions under which the measurements are conducted47. More recent, albeit limited, measurements of the carbonate ion concentration using microelectrodes report values of 600 to 1550 µmol kg−1 in the calcifying fluid44. These instantaneous measurements performed under laboratory conditions, while providing some informative results, have significant limitations. For instance, microelectrode measurements are currently unable to determine the dynamic seasonal interactions between components of the coral calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry (pHcf, DICcf, Ωcf) documented here under naturally fluctuating conditions. This is due to the limitations of existing technology, as measurements must be conducted using separate probes for pHcf and [CO3 2−]cf and under highly controlled laboratory conditions. Thus, our findings highlight the importance of δ11B and B/Ca proxies as a method for inferring the internal carbonate chemistry in corals under real-world conditions and over longer (i.e., seasonal) time scales.

Laboratory experiments have nevertheless demonstrated that coral pHcf typically shows a relatively consistent linear and muted response to changes in pHsw, such that changes in coral pHcf are usually equal to approximately one-third to one-half of those in pHsw 12,14,47–51. Thus, according to the results of those experiments, seasonal changes in coral pHcf should have been on the order of ~0.02 pH units, due to the relatively small seasonal variability in pHsw at Rottnest Island (~0.07; Supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, seasonal variations in pHcf are an order of magnitude higher (>0.2 pH units). Therefore, our results unequivocally demonstrate that seawater pH is not the major factor driving seasonal changes in coral pHcf up-regulation in this study.

Our current understanding of the sensitivity of the calcifying fluid chemical composition to changes in seawater carbonate chemistry has generally been inferred from controlled laboratory experiments14,47–51, which have kept other environmental conditions constant, such as temperature14,47–51 and/or light14,50,51. However, our findings demonstrate that other environmental factors beyond pHsw may have a much larger influence on pHcf and [CO3 2−]cf, at least on seasonal time-scales. For instance, the observed inverse relationship between seasonally varying pHcf and DICcf is suggestive of a deliberate mechanism to compensate for seasonal declines in temperature and light, and thus changes to the supply and/or transport of DIC necessary for coral growth21. The lower levels of DIC in the calcifying fluid during winter reflect a reduction in rates of carbon fixation by endosymbionts in winter and are compensated for by higher pHcf up-regulation (Fig. 3). Despite the stabilizing effects that a counter-cyclical seasonal relationship between pHcf and DICcf would have on Ωcf, we nonetheless show that Ωcf also varies seasonally. This seasonal behaviour of Ωcf may, at the very least, dampen any expected seasonality in rates of coral calcification.

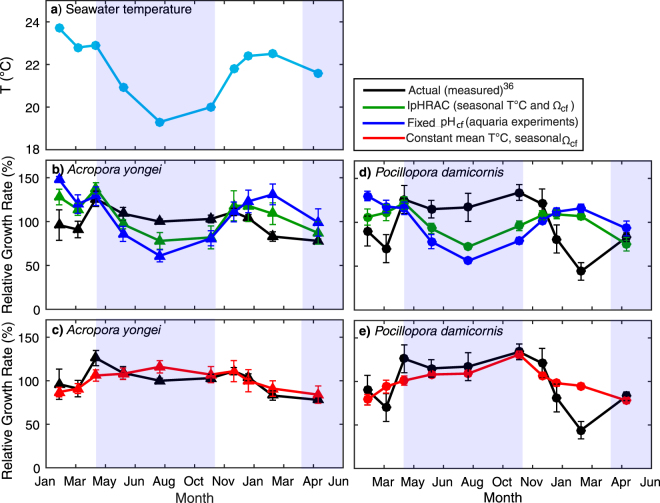

To better constrain the relative sensitivity of coral calcification rates to seasonal changes in both temperature and the carbonate chemistry of the calcifying fluid, calcification rates were modelled using the inorganic rate equation (see Eq. 5 in Methods)12. In this model, aragonite precipitation occurs according to abiotic rate kinetics under chemical conditions dictated by the living coral (e.g., elevated pHcf and DICcf). Three scenarios are considered: (1) temperature and Ωcf vary with season, (2) temperature, DICcf and Ωcf vary with season while pHcf is calculated based on seawater pHsw in accordance with the results of fixed aquaria experiments40,49, and (3) Ωcf varies with season, but temperature is kept constant at its annual average (21.7 °C). Modelled rates of calcification based on inorganic rate kinetics are a factor of 2 to 7 times lower than the measured calcification rates (see Supplementary Table S4). This indicates that an estimated Ωcf of 30 to 50 is required to attain the measured rates of calcification and thus much higher than our seasonal range of ~10 to 16, depending on taxa (Fig. 3d). Thus, physiological mechanisms must be operative in enhancing rates of skeletal precipitation relative to that expected from inorganic rate kinetics.

During summer, the higher DICcf supply is offset by a systematic reduction in pHcf to modulate Ωcf and calcification rates. While the estimated calcification rates from inorganic rate kinetics in scenario 1 are still ~50% higher at the peak in summer compared to the minima in winter, this seasonal change is nevertheless substantially less than the estimated ~90% seasonal change in calcification rates if pHcf levels were more or less constant year-round, as inferred from fixed condition aquaria experiments. Calcification rates estimated from both scenarios indicate that the seasonal variation in the measured coral calcification rates should be pro-cyclical with temperature and much greater than observed36 (Fig. 5). Thus, scenarios 1 and 2, which allow for the full seasonal variation in temperature to be expressed through the inorganic rate kinetics, exhibit large deviations from the measured calcification rates for A. yongei (Scenario 1: RMSE = 17.0%; Scenario 2: RMSE = 30.3%), and P. damicornis (Scenario 1: RMSE = 32.7%; Scenario 2: RMSE = 43.3%). There is a strong physiological control over Ωcf such that calcification rates appear to be modulated more by Ωcf, rather than temperature directly. We find that the calcification rates modelled under a constant mean temperature (i.e., scenario 3) show the best fit to the observed seasonal patterns in calcification (RMSE = 11.5% and 20.8%, respectively; Fig. 5). One possibility is that differences between the complex skeletal micro-architecture of coral growth (e.g., a higher active surface area on which precipitation can occur)15 compared to abiotic aragonite crystal formation could result in the enhanced rates of biologically-mediated coral calcification shown here. Another possibility is that other factors may influence seasonal patterns in rates of calcification, for example, changes in the speed at which the corals create organic matrices and crystal templates52–56 necessary for mineralization. This cannot be ruled out given that the calcification rate measurements are integrated over several weeks of biomineralization.

Figure 5.

Measured and modelled seasonal growth rate response for branching Acropora yongei and Pocillopora damicornis at Rottnest Island. (a) Seasonal changes in average seawater temperature (°C). Actual calcification rates measured using the buoyant weight technique36 and predicted calcification rates modelled using inorganic rate kinetics for (b,c) A. yongei, and (d,e) P. damicornis. Black symbols represent the measured calcification rates (mean ± 1 SE) for A. yongei (n = 16) and P. damicornis (n = 9)36. Green symbols represent the predicted calcification rates using seasonally varying temperature and seasonally varying Ωcf, blue symbols represent the predicted calcification rates using pHcf calculated from fixed condition experiments for Acropora spp., (y = 0.51pHsw + 4.2840,49; where pHsw ranged from 8.03–8.10), and red symbols represent the predicted rates using a constant mean temperature (21.7 °C) and seasonally varying Ωcf. All growth rates are expressed as percentage relative to the mean. Light blue shading denotes winter and unshaded areas denote summer, defined based on seasonal changes in temperature and light.

Although the relatively seasonally invariant calcification rates for corals from Rottnest Island stand in contrast with findings from more tropical environments24,33–35, there are also a number of studies36,39,57,58 that show limited seasonal variability in calcification rates for several coral species. These studies were conducted across a range of locations (i.e., spanning 10 degrees latitude) in Western Australia, and are thus widely applicable to reef-building corals growing in a various environments. There have been a number of hypotheses to explain this lack of seasonality, ranging from the residual effects of sub-lethal thermal stress following an unusually strong marine heat wave39, to higher rates of particulate nutrient uptake in winter36,37,57. In the present study, however, the limited seasonal variability in calcification rates can be explained by the seasonally counter-cyclical up-regulation of pHcf and DICcf to deliberately elevate Ωcf and support near-constant rates of calcification year-round, despite much cooler temperatures during winter. This apparent physiological control over the internal carbonate chemistry is further supported by the results from the Papua New Guinea CO2 seeps16 and Free Ocean Carbon Enrichment experiment (FOCE)11; both of which demonstrated the mechanism of pHcf ‘homeostasis’ in corals despite exposure to extreme variations in ambient pHsw.

We have now identified a key mechanism of chemical regulation within the calcifying fluid composition that assists reef-building coral to calcify year-round in sub-tropical conditions (i.e., lower and more seasonally variable temperature and light). While these findings are based on branching corals at Rottnest Island, they nevertheless demonstrate a key physiological mechanism whereby changes in the calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry act to modulate calcification rates. Although such robust regulation of chemical conditions during calcification will help protect the growth of adult corals from the influence of declining seawater pH12,15, it will not necessarily preclude corals from being vulnerable to thermal stress59. Thus, the future survival of coral reefs in the face of Earth’s rapidly changing climate will ultimately depend on the capacity of reef-building coral to endure the increasingly frequent and intense CO2-driven warming events59.

Methods

Overview

This study was conducted at Salmon Bay on the south side of Rottnest Island, which is located approximately 20 km west of Perth, WA (32°S, 115°E). See Ross et al.36 for a detailed map of study area. Single individual branches of A. yongei and P. damicornis were collected from four naturally growing colonies (1 branch per colony) every 1 to 3 months between February 2013 and March 2015 and subject to the geochemical analyses described herein.

Environmental data

Continuous measurements of seawater pHT (Total scale, with ±0.03 accuracy) were made using a SeaFET ocean pH sensor (Satlantic, Canada) in October 2014 (spring) and April 2015 (autumn). Earlier measurements were made in July 2013 (winter) and February 2014 (summer)36. Seawater temperature was continuously measured at the study site for the entire duration of the study using HOBO temperature loggers (±0.2 °C, Onset Computer Corp.). Daily down-welling planar photo-synthetically active radiation (PAR in mol m−2 d−1) was measured from December 2013 to July of 2014 using Odyssey light loggers (±5%, Odyssey Data Recording) that had been calibrated against a high-precision LiCor 192 A cosine PAR (±5%, LiCor Scientific) sensor36. For this location, seasons were defined as follows: winter from mid-April through to mid-October and summer from mid-November through to mid-April.

Boron isotopic and trace element analyses

The δ11B of coral skeletons were measured from the uppermost apical section of the growing tip of A. yongei and P. damicornis skeletons (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S5). We sampled ~4 mm of the apical growing tip based on our previous study36 showing average monthly extension rates of ~50 mm yr−1 (or ~4 mm month−1). Alternate methods for determining the sclero-chronology of the deposited skeletal material include using fluorescent staining60 or isotope labelling, which are informative for analysis by laser ablation-multi-collector-ICP-MS61. Unfortunately, repeated labelling of the coral colonies used in this study was not feasible due to the frequent (1 to 3 month) skeletal sampling resolution and long study period (i.e., ~2 years). Instead, we used molar ratios of strontium to calcium (Sr/Ca) and lithium to magnesium (Li/Mg) in the most recently deposited skeletal material and well-known, highly correlated relationships between these trace element ratios and ambient seawater temperature62 to confirm the seasonal chronology of skeletal growth histories11.

Powders derived from the temporally controlled samples of coral skeleton were cleaned63 and dissolved in 0.58 N HNO3. Aliquots of these acidified samples were analysed for trace elements (Sr/Ca, Li/Mg, and B/Ca) using an X-Series 2 Quadrupole Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The extraction and concentration of boron-rich solutions from acidified sample solutions was performed via paired cation-anion resin columns and analysed with a NU Plasma II (Nu Instruments, Wrexham, UK) multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICPMS)64.

Boron isotope pH-proxy

We determined the pH of the calcifying fluid from the measured δ11B values according to the following equation65:

| 1 |

where pK B is the dissociation constant of boric acid in seawater66 at the temperature and salinity of the seawater in Salmon Bay, δ11Bcarb and δ11BSW are the boron isotopic composition of the coral skeleton and average seawater, respectively, and αB is the isotopic fractionation factor (1.0272)67.

Estimation of DICcf and modelled rates of mineral precipitation

We estimate the concentration of carbonate ions at the site of calcification ([CO3 2−]cf) using molar ratios of boron to calcium (B/Ca) according to the following relationship45 simplified by McCulloch, et al.21:

| 2 |

where [B(OH)4 –]cf is the concentration of borate in the calcifying fluid, is the molar distribution coefficient for boron in aragonite, and [B/Ca]arag is the elemental ratio of boron to calcium in the coral skeleton. To estimate [B(OH)4 –]cf, we assume that the concentration of total inorganic boron in the calcifying fluid is salinity dependent68,69, and equal to that of the surrounding seawater. The strong linear relationship between the calculated [CO3 2−]cf(using eq. 2) and the measured [CO3 2−]cf from abiogenic experiments by Holcomb, et al. 45 is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. The relative amounts of borate are determined by the pHcf 66, as determined from the δ11B isotopic measurements (see eq. 1). The is calculated as a function of pHcf according to21,45:

| 3 |

where [H+] in the calcifying fluid is estimated from the coral δ11B derived pHcf and only varies by less than ± 3% over the range in which most coral pHcf are known to occur (8.3 to 8.6)21.

The concentration of DICcf is then calculated from pHcf (eq. 1) and [CO3 2−]cf (eq. 2).

The Ωcf is estimated from [Ca2+] and [CO3 2−] (from δ11B and B/Ca) according to the following relationship:

| 4 |

where K * sp is the solubility constant for aragonite as a function of temperature and salinity and [Ca2+] is assumed to be the same as the surrounding seawater values.

Finally, we used the combination of Ωcf and temperature to infer rates of abiotic aragonite precipitation (G) at the site of calcification according to the model of internal pH-regulation abiotic calcification model (IpHRAC)12:

| 5 |

where k and n are temperature-dependent empirical constants25.

Observed rates of coral calcification

Calcification rates (mg CaCO3 cm−2 d−1) for both A. yongei (n = 16) and P. damicornis (n = 9) were measured36 on individual coral colonies (mounted on plastic tiles and deployed in-situ) using the buoyant weight technique70,71. These calcification measurements were conducted on colonies from the same location and at the same time as when branches were collected (from separate colonies) for the analysis of skeletal geochemistry. This field-based approach allowed the comparison of seasonal changes of in-situ determined coral calcification rates36 with concomitant changes in seawater temperature, pH and DIC together with coral calcifying fluid pHcf and DICcf.

Availability of data

Data is available at the Zenodo Digital Repository (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1009710).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Thanks to A. Comeau, K. Rankenburg, M. Holcomb and J. Pablo D’Olivo for training and assistance in the coral isotope and mass spectrometry laboratories. We are grateful to H. Clarke, T. Foster, S. Dandan, V. Schoepf, B. Vaughan, and K. Williams for assisting on field trips. We also thank the staff at Rottnest Island Authority for their support of our fieldwork. This research was supported by funding provided by an ARC Laureate Fellowship (LF120100049) awarded to Professor M. McCulloch, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (CE140100020), and an Australian Post Graduate Scholarship awarded to C. Ross.

Author Contributions

C.R. designed the experiments, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.F. conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.M. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-14066-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Feely RA, et al. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 system in the oceans. Science (80). 2004;305:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1097329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orr J, et al. Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature. 2005;437:681–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Hooidonk R, Huber M. Effects of modeled tropical sea surface temperature variability on coral reef bleaching predictions. Coral Reefs. 2012;31:121–131. doi: 10.1007/s00338-011-0825-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donner SD, Skirving WJ, Little CM, Oppenheimer M, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Global assessment of coral bleaching and required rates of adaptation under climate change. Glob Chang. Biol. 2005;11:2251–2265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoegh-Guldberg O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1999;50:839. doi: 10.1071/MF99078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoepf V, Stat M, Falter JL, McCulloch MT. Limits to the thermal tolerance of corals adapted to a highly fluctuating, naturally extreme temperature environment. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17639. doi: 10.1038/srep17639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawall Y, et al. Extensive phenotypic plasticity of a Red Sea coral over a strong latitudinal temperature gradient suggests limited acclimatization potential to warming. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8940. doi: 10.1038/srep08940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marubini F, Ferrier-Pages C, Cuif J-P. Suppression of skeletal growth in scleractinian corals by decreasing ambient carbonate-ion concentration: a cross-family comparison. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003;270:179–84. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langdon C. Effect of elevated pCO2 on photosynthesis and calcification of corals and interactions with seasonal change in temperature/irradiance and nutrient enrichment. J. Geophys. Res. 2005;110:C09S07. doi: 10.1029/2004JC002576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuffner IB, Andersson AJ, Jokiel PL, Rodgers KS, Mackenzie FT. Decreased abundance of crustose coralline algae due to ocean acidification. Nat. Geosci. 2008;1:114–117. doi: 10.1038/ngeo100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgiou, L. et al. pH homeostasis during coral calcification in a free ocean CO2 enrichment (FOCE) experiment, Heron Island reef flat, Great Barrier Reef. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 201505586. 10.1073/pnas.1505586112 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.McCulloch MT, Falter JL, Trotter J, Montagna P. Coral resilience to ocean acidification and global warming through pH up-regulation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012;2:1–5. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holcomb M, et al. Coral calcifying fluid pH dictates response to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:5207. doi: 10.1038/srep05207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venn A, Tambutté É, Holcomb M, Allemand D, Tambutté S. Live tissue imaging shows reef corals elevate pH under their calcifying tissue relative to seawater. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venn AA, Tambutté É, Holcomb M, Laurent J, Allemand D. Impact of seawater acidification on pH at the tissue–skeleton interface and calcification in reef corals. PNAS. 2013;110:1634–1639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216153110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall, M. et al. Internal pH regulation facilitates in situ long-term acclimation of massive corals to end-of-century carbon dioxide conditions. Sci. Rep. 1–7, 10.1038/srep30688 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.McConnaughey, T. A. Ion transport and the generation of biomineral supersaturatioation in the 7th International Symposium Biomineralization (ed. Allemand, D. & Cuif, J.-P.) 1–18 (1994).

- 18.Allemand D, et al. Biomineralisation in reef-building corals: from molecular mechanisms to environmental control. Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2004;3:453–467. doi: 10.1016/j.crpv.2004.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ries JB. A physicochemical framework for interpreting the biological calcification response to CO2-induced ocean acidification. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2011;75:4053–4064. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka, K. et al. Response of Acropora digitifera to ocean acidification: constraints from δ11B, Sr, Mg, and Ba compositions of aragonitic skeletons cultured under variable seawater pH. Coral Reefs, 10.1007/s00338-015-1319-6 (2015).

- 21.McCulloch, M. T., D’Olivo Cordero, J., Falter, J. L. & Holcomb, M. Coral calcification in a changing World and the interactive dynamics of pH and DIC up-regulation. Nat. Commun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Veron, J. Corals in space and time: the biogeography and evolution of the Scleractinia. University of New South Wales Press, Ithaca, Sydney, 321 (Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, 1995).

- 23.Lough J, Barnes D. Environmental controls on growth of the massive coral. Porites. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2000;245:225–243. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(99)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall AT, Clode P. Calcification rate and the effect of temperature in a zooxanthellate and an azooxanthellate scleractinian reef coral. Coral Reefs. 2004;23:218–224. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton EA, Walter LM. Relative precipitation rates of aragonite and Mg calcite from seawater: Temperature or carbonate ion control? Geology. 1987;15:111. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1987)15<111:RPROAA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grottoli AG, et al. The cumulative impact of annual coral bleaching can turn some coral species winners into losers. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014;20:3823–3833. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jokiel P, Coles SL. Effects of Temperature on the Mortality and Growth of Hawaiian Reef Corals *. Mar Biol. 1977;208:201–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00402312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Horani F, Al-Moghrabi, de Beer D. The mechanism of calcification and its relation to photosynthesis and respiration in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Mar Biol. 2003;142:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00227-002-0981-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider K, Levy O, Dubinsky Z, Erez J. In situ diel cycles of photosynthesis and calcification in hermatypic corals. Limn Ocean. 2009;54:1995–2002. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.54.6.1995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crossland C. Seasonal variations in the rates of calcification and productivity in the coral Acropora formosa on a high-latitude reef. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1984;15:135–140. doi: 10.3354/meps015135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Martin S, Ferrier-Pagès C, Gattuso J-P. Response of the temperate coral Cladocora caespitosa to mid-and long-term exposure to pCO2 and temperature levels projected in 2100. Biogeosci Discuss. 2009;6:7103–7131. doi: 10.5194/bgd-6-7103-2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuffner IB, Hickey TD, Morrison JM. Calcification rates of the massive coral Siderastrea siderea and crustose coralline algae along the Florida Keys (USA) outer-reef tract. Coral Reefs. 2013;32:987–997. doi: 10.1007/s00338-013-1047-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venti A, Andersson A, Langdon C. Multiple driving factors explain spatial and temporal variability in coral calcification rates on the Bermuda platform. Coral Reefs. 2014;33:979–997. doi: 10.1007/s00338-014-1191-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roik, A., Roder, C., Röthig, T. & Voolstra, C. R. Spatial and seasonal reef calcification in corals and calcareous crusts in the central Red Sea. Coral Reefs35 (2015).

- 35.Vajed Samiei J, et al. Variation in calcification rate of Acropora downingi relative to seasonal changes in environmental conditions in the northeastern Persian Gulf. Coral Reefs. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross CL, Falter JL, Schoepf V, McCulloch MT. Perennial growth of hermatypic corals at Rottnest Island, Western Australia (32°S) PeerJ. 2015;3:e781. doi: 10.7717/peerj.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wyatt ASJ, Falter JL, Lowe RJ, Humphries S, Waite AM. Oceanographic forcing of nutrient uptake and release over a fringing coral reef. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2012;57:401–419. doi: 10.4319/lo.2012.57.2.0401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houlbrèque F, Tambutté E, Richard C, Ferrier-pagès C. Importance of a micro-diet for scleractinian corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;282:151–160. doi: 10.3354/meps282151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster T, Short J, Falter JL, Ross C, McCulloch MT. Reduced calcification in Western Australian corals during anomalously high summer water temperatures. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2014;461:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2014.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trotter J, et al. Quantifying the pH ‘vital effect’ in the temperate zooxanthellate coral Cladocora caespitosa: Validation of the boron seawater pH proxy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011;303:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei H, Jiang S, Xiao Y, Hemming NG. Boron isotopic fractionation and trace element incorporation in various species of modern corals in Sanya Bay, South China Sea. J. Earth Sci. 2014;25:431–444. doi: 10.1007/s12583-014-0438-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelejero C, et al. Preindustrial to modern interdecadal variability in coral reef pH. Science. 2005;309:2204–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1113692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allison N, Cohen I, Finch Aa, Erez J, Tudhope AW. Corals concentrate dissolved inorganic carbon to facilitate calcification. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5741. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai W-J, et al. Microelectrode characterization of coral daytime interior pH and carbonate chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11144. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holcomb M, DeCarlo TM, Gaetani GA, McCulloch MT. Factors affecting B/Ca ratios in synthetic aragonite. Chem. Geol. 2016;437:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gagnon AC. Coral calcification feels the acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1567–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221308110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hönisch B, et al. Assessing scleractinian corals as recorders for paleo-pH: Empirical calibration and vital effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2004;68:3675–3685. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2004.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marubini F, Barnett H, Langdon C, Atkinson MJ. Dependence of calcification on light and carbonate ion concentration for the hermatypic coral Porites compressa. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2001;220:153–162. doi: 10.3354/meps220153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reynaud, S., Hemming, N. G., Juillet-Leclerc, A. & Gattuso, J.-P. Effect of pCO2 and temperature on the boron isotopic composition of the zooxanthellate coral Acropora sp. Coral Reefs 539–546 (2004).

- 50.Marubini F, Ferrier-Pagès C, Furla P, Allemand D. Coral calcification responds to seawater acidification: a working hypothesis towards a physiological mechanism. Coral Reefs. 2008;27:491–499. doi: 10.1007/s00338-008-0375-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krief S, et al. Physiological and isotopic responses of scleractinian corals to ocean acidification. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2010;74:4988–5001. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tambutté S, et al. Characterization and role of carbonic anhydrase in the calcification process of the azooxanthellate coral Tubastrea aurea. Mar. Biol. 2007;151:71–83. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0452-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mass T, et al. Cloning and characterization of four novel coral acid-rich proteins that precipitate carbonates in vitro. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1126–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tambutté E, et al. Morphological plasticity of the coral skeleton under CO2-driven seawater acidification. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7368. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clode PL, Marshall AT. Calcium associated with a fibrillar organic matrix in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Protoplasma. 2003;220:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s00709-002-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Falini G, Fermani S, Goffredo S. Coral biomineralization: A focus on intra-skeletal organic matrix and calcification. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;46:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Falter JL, Lowe RJ, Atkinson MJ, Cuet P. Seasonal coupling and de-coupling of net calcification rates from coral reef metabolism and carbonate chemistry at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:C05003. doi: 10.1029/2011JC007268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dandan, S. S., Falter, J. L., Lowe, R. J. & McCulloch, M. T. Resilience of coral calcification to extreme temperature variations in the Kimberley region, northwest Australia. Coral Reefs, 10.1007/s00338-015-1335-6 (2015).

- 59.Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. Coral reefs under rapidclimate change and ocean acidification. Science (80-.). 2007;318:1737–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.1152509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holcomb M, Cohen AL, McCorkle DC. An evaluation of staining techniques for marking daily growth in scleractinian corals. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2013;440:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2012.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fietzke J, et al. Boron isotope ratio determination in carbonates via LA-MC-ICP-MS using soda-lime glass standards as reference material. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2010;25:1953–1957. doi: 10.1039/c0ja00036a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Montagna P, et al. Li/Mg systematics in scleractinian corals: Calibration of the thermometer. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2014;132:288–310. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holcomb M, et al. Cleaning and pre-treatment procedures for biogenic and synthetic calcium carbonate powders for determination of elemental and boron isotopic compositions. Chem. Geol. 2015;398:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2015.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCulloch MT, Holcomb M, Rankenburg K, Trotter Ja. Rapid, high-precision measurements of boron isotopic compositions in marine carbonates. Rapid Commun. mass Spectrom. RCM. 2014;28:2704–12. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeebe, R. & Wolf-Gladrow, D. CO2 in Seawater: Equilibrium, Kinetics, Isotopes in Elsevier OceanographySeries (Ed. Richard, E. Z., Dieter, W.G.) 65, 1–84 (Elsevier Science, 2001).

- 66.Dickson AG. Thermodynamics of the dissociation of boric acid in synthetic seawater from 273.15 to 318.15 K. Deep Sea Res. Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1990;37:755–766. doi: 10.1016/0198-0149(90)90004-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klochko K, Kaufman AJ, Yao W, Byrne RH, Tossell JA. Experimental measurement of boron isotope fractionation in seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006;248:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2006.05.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Foster GL, Pogge von Strandmann PAE, Rae JWB. Boron and magnesium isotopic composition of seawater. Geochemistry, Geophys. Geosystems. 2010;11:1–10. doi: 10.1029/2010GC003201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lewis, E., Wallace, D. & Allison, L. Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1998).

- 70.Bak R. Coral weight increment in situ. A new method to determine coral growth. Mar Biol. 1973;20:45–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00387673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jokiel, P., Maragos, J. & Franzisket, L. Coral growth: buoyant weight technique in Coral reefs: research methods (ed. Stoddart, D. & Johannes, R. E.) 529–542 (UNESCO, 1978).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.