Abstract

Background

Elderly patients with aged physical status and increased underlying disease suffered from more postoperative complication and mortality. We design this retrospective cohort study to investigate the relationship between existing comorbidity of elder patients and 30 day post-anesthetic mortality by using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) from Health Insurance Database.

Methods

Patients aged above 65 years old who received anesthesia between 2000 and 2010 were included from 1 million Longitudinal Health Insurance Database in (LHID) 2005 in Taiwan. We use age, sex, type of surgery to calculate propensity score and match death group and survival one with 1:4 ratio (death: survival = 1401: 5823). Multivariate logistic model with stepwise variable selection was employed to investigate the factors affecting death 30 days after anesthesia.

Results

Thirty seven comorbidities can independently predict the post-anesthetic mortality. In our study, the leading comorbidities predict post-anesthetic mortality is chronic renal disease (OR = 2.806), acute myocardial infarction (OR = 4.58), and intracranial hemorrhage (OR = 3.758).

Conclusions

In this study, we present the leading comorbidity contributing to the postoperative mortality in elderly patients in Taiwan from National Health Insurance Database. Chronic renal failure is the leading contributing comorbidity of 30 days mortality after anesthesia in Taiwan which can be explained by the great number of hemodialysis and prolong life span under National Taiwan Health Insurance. Large scale database can offer enormous information which can help to improve quality of medical care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-017-0629-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Post-anesthesia mortality

Background

Increased life expectancy, improvement of anesthesia safety and less invasive surgical techniques have made greater number of geriatric patients receive surgical intervention. With aged physical status and increased underlying disease, the risk of anesthesia and postoperative complication and mortality is much higher than other populations [1, 2].

The main four factors of surgical risk and outcome in patients older than 65 years old are age,physiologic status,coexisting disease, and type of procedure [3, 4]. Earlier studies suggest that anesthetic complications are related to age and some studies also have corroborated an association of mortality and morbidity with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA-PS) scores. The surgical procedure itself significantly influence postoperative risk and it can be classified to low, intermediate, and high-risk surgery [5].

The ASA-PS classification introduced to clinical practice since 1941 was used worldwide to quantify the amount of physiological reserve that a patient possesses when assessed before a surgical procedure. This classification is validated as a reliable independent predictor of medical complications and mortality following surgery in peer review articles [6, 7]. However, the ASA-PS scale has unreliability due to its inherent subjectivity which resulted in different ASA class rated in one patient by different anesthesiologists [8]. It is useful but lack of scientific precision.

To date, national health insurance database in Taiwan has recruited most patients’ information and medical record for more than 10 years. Several studies have been published by using the reimbursement claims data of Taiwan’s national Health Insurance [9–11]. We design this retrospective cohort study to investigate the relationship of existing comorbidity of geriatric patients who came for anesthesia with 30 day post-anesthetic mortality rate by using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). We hope to investigate the impact of different underlying comorbidity of the geriatric patient on post-anesthesia mortality.

Methods

Data base

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance was put into practice since 1995 and covered more than 22.6 million residents in Taiwan. Taiwan’s National Health Research Institutes established a National Health Research Database which record all in-patient and out-patient medical services for research [9]. This study used the 1 million Longitudinal Health Insurance Database in 2005 (LHID), which means 1 million patients were randomly enrolled in 2005 and the longitudinal database included all the issue from 2000 to 2010. The database was decoded with patient identifications to protect patients’ privacy and scrambled for further public access. This study was approved by National Taiwan University Hospital Ethics Committee (201411078RINC) and inform consent was waived.

Study sample

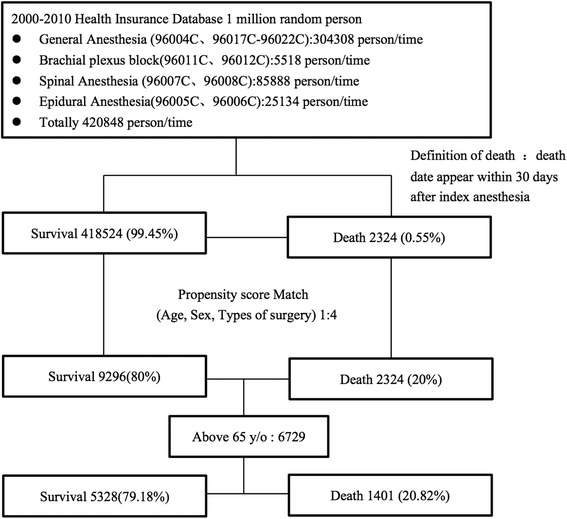

The study sample is the patients aged above 65 years old and received anesthesia between 2000 and 2010. There were 420,848 index surgery requiring anesthesia in this period, including general anesthesia 304,308 times, brachial plexus block 5518 times, spinal anesthesia 85,888 times, and epidural anesthesia 2,5134 times. We defined mortality as death date appeared within 30 days after index surgery whether in hospital or not. There were 2324 death and 418,524 survival after index surgery. Due to tremendous difference in population, we use age, sex, type of surgery to calculate propensity score [12, 13] and match death and survival group with 1:4. Among them, there were 6729 patients aged above 65 years old and 1401 patients were dead (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study design

Key variable of interest

We use International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) appeared 2 years before index surgery in our database as comorbidity. The definition of comorbidity means the patient was diagnosed for more than 3 times and the interval was more than 28 days which including ischemic heart disease, hypertension, heart failure, vascular disease, respiratory disease, disease of liver and biliary tract, disease of GI system, urinary disease, endocrine disease, musculoskeletal disease, infectious disease, CVA or trauma, cancer, other disease..(Additional file 1) Due to disease categorization is complex, we therefore aggregated codes into disease group to resemble clinical pre-anesthetic usage. This process was conducted independently by three anesthesiologists.

Statistical analysis

The difference of comorbidity in death and survival group 30 days after index surgery was analyzed by Chi-Square test. We use conditional logistic regression to correct age, gender, type of surgery and other comorbidity, then analysis the correlation of comorbidity with death. Multivariate logistic model with stepwise variable selection [14] was employed to investigate the factors affecting death 30 days after anesthesia. We perform calculation by SAS statistical package (SAS System for Windows, Version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

More than one hundred codes were given out when we count all the comorbidity ICD-9 code in death group. Seventy three codes were selected after aggregation by expertise. (Additional file 1) All the comorbidity was compared by chi square test under 1:4 ratio by matching age, sex, type of surgery as Table 1 listed. Age and sex were both statistically significant after propensity score matching. The crude odds ratio and adjusted odds of each comorbidity (Table 2) was counted and then 37 leading comorbidities (Table 3) which can independently predict 30 days post-anesthetic mortality in geriatric patients were ranked by multivariate logistic model with stepwise variable selection. In our study, the leading comorbidities predict post-anesthetic mortality is chronic renal disease, acute myocardial infarction, and intracerebral hemorrhage.

Table 1.

Correlation analysis of comorbidity and mortality in more than 65-year-old patients, N = 6729 (match 1:4)

| Comorbidity | Non-Death (N = 5823) |

Death (N = 1401) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age(mean,sd) | 76.72 | 7.08 | 78.08 | 7.41 | <.0001 |

| Sex(Male) | 3563 | 66.87 | 855 | 61.03 | <.0001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | |||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 66 | 1.24 | 68 | 4.85 | <.0001 |

| Coronary atherosclerosis of native coronary artery | 661 | 12.41 | 251 | 17.92 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1556 | 29.2 | 616 | 43.97 | <.0001 |

| Heart failure | |||||

| Heart failure | 232 | 4.35 | 155 | 11.06 | <.0001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 106 | 1.99 | 66 | 4.71 | <.0001 |

| Vascular disease | |||||

| Arterial embolism and thrombosis of lower extremity | 39 | 0.73 | 26 | 1.86 | 0.0002 |

| Gangrene | 106 | 1.99 | 66 | 4.71 | <.0001 |

| Respiratory disease | |||||

| Pneumonia, organism unspecified | 339 | 6.36 | 165 | 11.78 | <.0001 |

| Pneumonitis due to inhalation of food or vomitus | 61 | 1.14 | 18 | 1.28 | 0.7694 |

| Empyema, without mention of fistula | 13 | 0.24 | 9 | 0.64 | 0.0393 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 471 | 8.84 | 162 | 11.56 | 0.0022 |

| Pleurisy, unspecified pleural effusion | 27 | 0.51 | 12 | 0.86 | 0.1812 |

| Pulmonary insufficiency following trauma and surgery | 263 | 4.94 | 88 | 6.28 | 0.0515 |

| Disease of liver and biliary tract | |||||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 260 | 4.88 | 97 | 6.92 | 0.003 |

| Disease of GI system | |||||

| Gastric ulcer, chronic or unspecified with hemorrhage | 303 | 5.69 | 141 | 10.06 | <.0001 |

| Acute vascular insufficiency of intestine | 21 | 0.39 | 30 | 2.14 | <.0001 |

| Intestinal or peritoneal adhesions with obstruction | 133 | 2.5 | 52 | 3.71 | 0.0171 |

| Hemorrhage of gastrointestinal tract | 77 | 1.45 | 64 | 4.57 | <.0001 |

| Gastric ulcer,chronic or unspecified with perforation | 303 | 5.69 | 141 | 10.06 | <.0001 |

| Duodenal ulcer, chronic or unspecified with perforation | 164 | 3.08 | 93 | 6.64 | <.0001 |

| Peptic ulcer, site unspecified, chronic or unspecified with perforation | 482 | 9.05 | 181 | 12.92 | <.0001 |

| Acute appendicitis, with generalized peritonitis | 60 | 1.13 | 11 | 0.79 | 0.3348 |

| Peritonitis | 9 | 0.17 | 20 | 1.43 | <.0001 |

| Perforation of intestine | 59 | 1.11 | 37 | 2.64 | <.0001 |

| Urinary disease | |||||

| Tuberculosis of ureter, tubercle bacilli found | 52 | 0.98 | 48 | 3.43 | <.0001 |

| Unspecified hypertensive renal disease with renal failure | 58 | 1.09 | 27 | 1.93 | 0.0180 |

| Acute renal failure | 50 | 0.94 | 28 | 2 | 0.0016 |

| Chronic renal failure | 206 | 3.87 | 159 | 11.35 | <.0001 |

| Hydronephrosis | 31 | 0.58 | 9 | 0.64 | 0.9465 |

| Calculus of ureter | 227 | 4.26 | 27 | 1.93 | <.0001 |

| Urinary tract infection, site not specified | 662 | 12.42 | 239 | 17.06 | <.0001 |

| Hypertrophy (benign) of prostate | 948 | 17.79 | 214 | 15.27 | 0.0293 |

| Endocrine disease | 845 | 15.86 | 377 | 26.91 | <.0001 |

| Musculoskeletal disease | |||||

| Decubitus ulcer | 94 | 1.76 | 50 | 3.57 | <.0001 |

| Spinal stenosis, lumbar region | 1091 | 20.48 | 329 | 23.48 | 0.0156 |

| Pathologic fracture of vertebrae | 334 | 6.27 | 101 | 7.21 | 0.2253 |

| Fracture of intertrochanteric section of femur | 388 | 7.28 | 157 | 11.21 | <.0001 |

| Infectious disease | |||||

| Unspecified septicemia | 62 | 1.16 | 12 | 0.86 | 0.4026 |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 93 | 1.75 | 42 | 3 | 0.0041 |

| Bacteremia | 41 | 0.77 | 12 | 0.86 | 0.8744 |

| CVA or trauma | |||||

| Obstructive hydrocephalus | 91 | 1.71 | 28 | 2 | 0.5349 |

| Other conditions of brain | 16 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.64 | 0.1039 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 16 | 0.3 | 25 | 1.78 | <.0001 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 106 | 1.99 | 82 | 5.85 | <.0001 |

| Subdural hemorrhage | 70 | 1.31 | 14 | 1 | 0.4189 |

| Unspecified cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction | 382 | 7.17 | 170 | 12.13 | <.0001 |

| Other shock without mention of trauma | 106 | 1.99 | 66 | 4.71 | <.0001 |

| Other and unspecified cerebral laceration | 24 | 0.45 | 16 | 1.14 | 0.0051 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage following injury | 128 | 2.4 | 84 | 6 | <.0001 |

| Other and unspecified intracranial hemorrhage | 20 | 0.38 | 13 | 0.93 | 0.0155 |

| Fracture of vault of skull, closed | 6 | 0.11 | 6 | 0.43 | 0.0327 |

| Fracture of base of skull, closed | 11 | 0.21 | 12 | 0.86 | 0.0006 |

| Cancer | |||||

| Malignant neoplasm of tongue, unspecified | 10 | 0.19 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.5570 |

| Malignant neoplasm of cheek mucosa | 19 | 0.36 | 7 | 0.5 | 0.5989 |

| Malignant neoplasm of nasopharynx, unspecified | 8 | 0.15 | 3 | 0.21 | 0.8761 |

| Malignant neoplasm of hypopharynx, unspecified | 8 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.7588 |

| Malignant neoplasm of upper third of esophagus | 12 | 0.23 | 9 | 0.64 | 0.0263 |

| Malignant neoplasm of pyloric antrum of stomach | 66 | 1.24 | 29 | 2.07 | 0.0265 |

| Malignant neoplasm of sigmoid colon | 175 | 3.28 | 52 | 3.71 | 0.4810 |

| Malignant neoplasm of recto sigmoid junction | 125 | 2.35 | 33 | 2.36 | 1.0000 |

| Malignant neoplasm of liver, primary | 59 | 1.11 | 43 | 3.07 | <.0001 |

| Malignant neoplasm of head of pancreas | 16 | 0.3 | 13 | 0.93 | 0.0031 |

| Malignant neoplasm of upper lobe, bronchus or lung | 52 | 0.98 | 48 | 3.43 | <.0001 |

| Malignant neoplasm of female breast, unspecified | 47 | 0.88 | 5 | 0.36 | 0.0678 |

| Malignant neoplasm of cervix uteri, unspecified | 29 | 0.54 | 4 | 0.29 | 0.3082 |

| Malignant neoplasm of ovary | 2 | 0.04 | 3 | 0.21 | 0.1079 |

| Malignant neoplasm of prostate | 103 | 1.93 | 23 | 1.64 | 0.5449 |

| Malignant neoplasm of bladder, part unspecified | 131 | 2.46 | 33 | 2.36 | 0.9000 |

| Secondary and unspecified malignant neoplasm of lymph nodes of head, face | 6 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.14 | 1.0000 |

| Secondary malignant neoplasm of lung | 21 | 0.39 | 11 | 0.79 | 0.0940 |

| Secondary malignant neoplasm of skin | 26 | 0.49 | 25 | 1.78 | <.0001 |

| Other diseases | |||||

| Encounter for chemotherapy | 48 | 0.9 | 42 | 3 | <.0001 |

| Mechanical complication of other vascular device, implant and graft | 150 | 2.82 | 55 | 3.93 | 0.0390 |

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of comorbidity and morality in more than 65-year-old patients, N = 6729 (match 1:4)

| Comorbidity | Crude Odds ratio | Adjusted Odds ratioa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95%CI) | OR | (95%CI) | |||

| Age(mean,sd) | 1.026 | 1.018 | 1.035 | 1.024 | 1.015 | 1.034 |

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 4.067 | 2.883 | 5.737 | 4.503 | 3.060 | 6.627 |

| Hypertension | 1.902 | 1.686 | 2.147 | 1.406 | 1.223 | 1.616 |

| Heart failure | ||||||

| Heart failure | 2.732 | 2.209 | 3.38 | 1.800 | 1.404 | 2.309 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 2.436 | 1.781 | 3.331 | 1.894 | 1.333 | 2.690 |

| Vascular disease | ||||||

| Arterial embolism and thrombosis of lower extremity | 2.564 | 1.556 | 4.227 | 1.988 | 1.145 | 3.45 |

| Respiratory disease | ||||||

| Pneumonia, organism unspecified | 1.965 | 1.615 | 2.39 | 1.448 | 1.14 | 1.838 |

| Empyema, without mention of fistula | 2.643 | 1.128 | 6.197 | 3.272 | 1.307 | 8.194 |

| Disease of GI system | ||||||

| Gastric ulcer, chronic or unspecified with hemorrhage | 1.856 | 1.506 | 2.288 | 1.381 | 1.079 | 1.768 |

| Acute vascular insufficiency of intestine | 5.528 | 3.155 | 9.685 | 6.225 | 3.382 | 11.457 |

| Hemorrhage of gastrointestinal tract | 3.264 | 2.331 | 4.572 | 1.868 | 1.259 | 2.772 |

| Duodenal ulcer, chronic or unspecified with perforation | 2.239 | 1.724 | 2.908 | 2.209 | 1.637 | 2.982 |

| Peritonitis | 8.559 | 3.889 | 18.838 | 8.855 | 3.653 | 21.47 |

| Perforation of intestine | 2.423 | 1.599 | 3.67 | 2.636 | 1.67 | 4.162 |

| Urinary disease | ||||||

| Tuberculosis of ureter, tubercle bacilli found | 3.6 | 2.421 | 5.353 | 3.699 | 2.347 | 5.831 |

| Chronic renal failure | 3.183 | 2.565 | 3.95 | 2.931 | 2.241 | 3.834 |

| Calculus of ureter | 0.442 | 0.295 | 0.661 | 0.588 | 0.376 | 0.919 |

| Hypertrophy (benign) of prostate | 0.833 | 0.709 | 0.979 | 0.764 | 0.628 | 0.928 |

| Endocrine disease | 0.512 | 0.445 | 0.588 | 0.668 | 0.568 | 0.785 |

| Musculoskeletal disease | ||||||

| Fracture of intertrochanteric section of femur, closed | 1.607 | 1.321 | 1.954 | 1.284 | 1.023 | 1.613 |

| Infectious disease | ||||||

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 1.74 | 1.203 | 2.517 | 1.580 | 1.041 | 2.397 |

| CVA or trauma | ||||||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 6.027 | 3.209 | 11.318 | 8.935 | 4.612 | 17.312 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 3.063 | 2.281 | 4.112 | 3.893 | 2.803 | 5.408 |

| Subdural hemorrhage | 0.758 | 0.426 | 1.35 | 0.464 | 0.237 | 0.906 |

| Unspecified cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction | 1.788 | 1.477 | 2.165 | 1.512 | 1.216 | 1.881 |

| Other and unspecified cerebral laceration | 2.553 | 1.353 | 4.819 | 3.058 | 1.513 | 6.178 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage following injury | 2.591 | 1.955 | 3.434 | 4.12 | 3.014 | 5.632 |

| Fracture of vault of skull, closed | 3.815 | 1.229 | 11.847 | 5.197 | 1.521 | 17.755 |

| Fracture of base of skull, closed | 4.176 | 1.839 | 9.484 | 6.424 | 2.666 | 15.478 |

| Cancer | ||||||

| Malignant neoplasm of upper third of esophagus | 2.87 | 1.207 | 6.824 | 3.624 | 1.394 | 9.422 |

| Malignant neoplasm of pyloric antrum of stomach | 1.687 | 1.086 | 2.621 | 2.045 | 1.251 | 3.341 |

| Malignant neoplasm of liver, primary | 2.828 | 1.9 | 4.208 | 2.944 | 1.826 | 4.745 |

| Malignant neoplasm of head of pancreas | 3.109 | 1.492 | 6.478 | 4.035 | 1.809 | 9.002 |

| Malignant neoplasm of female breast, unspecifie | 0.402 | 0.16 | 1.014 | 0.335 | 0.119 | 0.939 |

| Secondary malignant neoplasm of skin | 3.705 | 2.133 | 6.436 | 3.418 | 1.796 | 6.506 |

| Other diseases | ||||||

| Encounter for chemotherapy | 3.4 | 2.237 | 5.166 | 2.566 | 1.531 | 4.301 |

aAdjusted variables including age, gender, types of surgery, comorbidity

Table 3.

Predictors of mortality in more than 65-year-old patients, N = 6729 (By stepwise)

| Comorbidity | step | Adjusted Odds ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95%CI) | |||

| Chronic renal failure | 1 | 2.806 | 2.205 | 3.571 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2 | 4.58 | 3.135 | 6.691 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 3 | 3.758 | 2.724 | 5.184 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage following injury | 4 | 3.937 | 2.891 | 5.363 |

| Tuberculosis of ureter, tubercle bacilli found | 5 | 3.573 | 2.282 | 5.594 |

| Heart failure | 6 | 1.863 | 1.463 | 2.371 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 7 | 8.654 | 4.473 | 16.742 |

| Duodenal ulcer, chronic or unspecified with perforation | 8 | 2.262 | 1.688 | 3.033 |

| Acute vascular insufficiency of intestine | 9 | 6.406 | 3.503 | 11.716 |

| Peritonitis | 10 | 9.242 | 3.872 | 22.063 |

| Endocrine disease | 11 | 0.656 | 0.559 | 0.768 |

| Age(mean,sd) | 12 | 1.024 | 1.015 | 1.034 |

| Malignant neoplasm of liver | 13 | 3.193 | 2.042 | 4.992 |

| Encounter for chemotherapy | 14 | 2.739 | 1.667 | 4.501 |

| Perforation of intestine | 15 | 2.683 | 1.705 | 4.222 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 16 | 1.963 | 1.388 | 2.776 |

| Fracture of base of skull, closed with subarchn | 17 | 6.619 | 2.812 | 15.58 |

| Sex(Male) | 18 | 0.762 | 0.659 | 0.881 |

| Unspecified cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction | 19 | 1.514 | 1.221 | 1.877 |

| Hemorrhage of gastrointestinal tract | 20 | 1.903 | 1.291 | 2.805 |

| Secondary malignant neoplasm of skin | 21 | 3.328 | 1.787 | 6.199 |

| Malignant neoplasm of head of pancreas | 22 | 3.89 | 1.753 | 8.633 |

| Malignant neoplasm of pyloric antrum of stomach | 23 | 2.035 | 1.253 | 3.304 |

| Pneumonia, organism unspecified | 24 | 1.397 | 1.115 | 1.751 |

| Other and unspecified cerebral laceration | 25 | 3.051 | 1.524 | 6.109 |

| Hypertrophy (benign) of prostate | 26 | 0.78 | 0.645 | 0.943 |

| Gastric ulcer, chronic or unspecified with hemorrhage | 27 | 1.403 | 1.103 | 1.784 |

| Fracture of vault of skull, closed | 28 | 4.976 | 1.451 | 17.06 |

| Malignant neoplasm of upper third of esophagus | 29 | 3.391 | 1.315 | 8.742 |

| Empyema, without mention of fistula | 30 | 3.22 | 1.297 | 7.997 |

| Arterial embolism and thrombosis of lower extremity | 31 | 1.952 | 1.122 | 3.394 |

| Malignant neoplasm of female breast | 32 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.868 |

| Subdural hemorrhage | 33 | 0.47 | 0.244 | 0.903 |

| Gastric ulcer, chronic or unspecified with hemorrhage | 34 | 1.403 | 1.103 | 1.784 |

| Calculus of ureter | 35 | 0.621 | 0.403 | 0.959 |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 36 | 1.591 | 1.052 | 2.407 |

| Fracture of intertrochanteric section of femur, closed | 37 | 1.285 | 1.026 | 1.61 |

Discussion

With better medical quality and living condition, geriatric patient population is growing and often pose a significant challenge in surgery and anesthesia. Geriatric patients are relative fragile and also develop more complication after anesthesia than general population [1, 15]. The most common postoperative complication is pulmonary complication and the secondary is cardiac event, leading to longer hospitalization and increased mortality. In previous study in Taiwan, relationship between postoperative complications and mortality risk was established, but there was no analysis between preoperative comorbidities and post-operative mortality. The leading preoperative comorbidities were listed as following: Hypertension, Diabetes mellitus, Coronary artery disease, Pulmonary disease, Malignancy, Hepatic dysfunction, and Renal dysfunction. Detailed evaluation and better communicating the aforementioned risk factors to these patients before operation are suggested for improving anesthesia quality and surgical outcomes [16].

A comprehensive geriatric assessment including Activities of Daily Living (IADL), cognitive function, nutrition status, and past medical history were used to predict postoperative morbidity and mortality in geriatric patients who received elective surgery [17, 18]. They came to a conclusion that aging itself not increase surgical risk, rather, the increasing prevalence of chronic disease and the deterioration of the organ’s functions, might increase the risk of postoperative mortality. Geriatric patients tend to carry more than one comorbidity and it is a risk factor for functional decline, disability, dependency, and institutionalization. Risk of functional decline and deterioration of the organ’s functions following comorbidities rather than age itself play an more important role in geriatric patients surgical risk assessment.

In 2015, several large scale study concerning postoperative morbidity and mortality were published, including using multidimensional frailty score to predict postoperative complications in older female cancer patients [18], peer review reporting ASA classification as a reliable independent predictor of medical complications and mortality following surgery [7], a retrospective cohort study using national anesthesia clinical outcome registry [19] on perioperative mortality in 2010 to 2014, the effect of adding functional classification to ASA status for predicting 30-day mortality [20], and newly established preoperative score to predict postoperative mortality (POSPOM) [21]. All the above indicate that the lacking and desiring of an objective preoperative evaluation tool to predict perioperative risk and morbidity.

This is the first retrospective cohort study investigating relationship of comorbidity of elder patients with 30 day post-anesthetic mortality rate using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) from Taiwan Health Insurance database. We solely investigated disease code in our study to diminish other man-made bias in the health insurance database and aggregated them into 73 comorbidities by expertise to include most comorbidities. We also adopted death date to include both in-hospital and out-of-hospital death to avoid mortality bias. We used 1:4 propensity score matching case control to select comparable controls, but there were still significant differences in age and sex proportions (p < 0.001). A possible explanation is that the large sample size in the present study might be the reason for the statistical significance, but not clinically significant [22]. For example, the difference between 76 years old in non-death group and 78 years old in death group. Multivariate logistic model with stepwise variable selection was then applied to analysis the ability of comorbidities to predict postoperative mortality. From the 33 comorbidities, the leading comorbidity predicts post-anesthetic mortality in order is chronic renal failure, acute myocardial infarction, and intracerebral hemorrhage.

In the past, cardiovascular disease was regarded as the leading comorbidity that contribute to aged patients’ functional decline [23]. Due to poor cardiopulmonary reserve, limited daily activity and function capacity resulted in disability and institutionalization. However, chronic renal dysfunction was found to have better predicting ability to postoperative mortality than myocardia infarction by stepwise variable selection in our study. This can be explained by the increasing number of hemodialyzed patients in Taiwan after National Health Insurance put into practice. Due to low cost of insurance fee, patients with chronic renal failure received more medical care and have longer life span. However, multiple organ system deteriorated rapidly and thromboembolic events increased with longer duration of hemodialysis [24]. Amputation and artificial vascular surgery put these patients in a higher mortality rate after anesthesia [25]. Chronic kidney disease associated with increased risk of death, increased cardiovascular events and hospitalization was proven [26] and it also increased adverse outcome after elective orthopedic, general, and vascular surgery [27].

The secondary leading comorbidity predicting post-anesthetic mortality was acute myocardial infarction compatible as other studies. Risks related to the patient and related to surgery are both high for unstable hemodynamic status and emergent coronary artery bypass. A recent myocardial infarction remains a significant risk factor for postoperative MI and mortality and postponing elective operation after optimizing medical treatment is suggested [28]. Intracerebral hemorrhage was the tertiary leading comorbidity which is correlated with hemorrhagic stroke and traumatic injury accompany with poor outcome. Intracerebral hemorrhage is the most devastating type of stroke leading to greatest mortality and it is also an important public health problem leading to high rates of disability in geriatric patients [29]. Post-operative mortality is high in patients diagnosed as intracerebral hemorrhage undergoing blood evacuation.

In Current era of informative age, large scale of medical data was stored and established as a database in the national health insurance institute. From that, enormous amount of information can be acquired and work up. The limitation of our study is that our database is 1 million Longitudinal Health Insurance Database in 2005. The population is small and the data is old. The international classification of disease(ICD-9) had revised to 10th version and aggregation of ICD-9 codes made man-made bias. Besides, functional classification of ASA and geriatric dysfunction assessment were not included in the database of National Taiwan Health Insurance. Better registration system and further studies were warranted.

Conclusions

We design this study to present the leading comorbidity contributing to the postoperative mortality in elderly patients in Taiwan from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Database. In our study, we diminish the impact of type of surgery, age, and sex by using matched propensity score and we use death date as the definition of mortality, which include in-hospital and out-of-hospital mortality. We concluded that chronic renal failure, acute myocardial infarction, and intracerebral hemorrhage are the leading comorbidity contribute to post-anesthetic mortality in geriatric patients in Taiwan. Our findings highlight the clinical importance of chronic renal failure in geriatric population.

Acknowledgements

None to report.

Funding

None to report.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan.

Additional file

Original and operating code. We aggregated original codes into disease group to resemble clinical pre-anesthetic usage, and called it operating code. This process was conducted independently by three anesthesiologists. (DOCX 78 kb)

Authors’ contributions

C.CL: writing the first draft, design the study. C.HY: critical revision for important intellectual content. C.WH: acquisition of data, data analysis. C.PY: data analysis. H.YY: supervision, critical revision. Y.HM: design the study, writing the first draft. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

National Taiwan University Hospital Ethics Committee (201411078RINC) and inform consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-017-0629-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Chun-Lin Chu, Email: cclgenie@yahoo.com.tw.

Hung-Yi Chiou, Email: hychiou@tmu.edu.tw.

Wei-Han Chou, Email: brokenarrowchou@hotmail.com.

Po-Ya Chang, Email: rj0729@hotmail.com.

Yi-You Huang, Email: yyhuang@ntu.edu.tw.

Huei-Ming Yeh, Phone: 886-2-2312-3456, Email: y.y.hhmm@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Luger TJ, Kammerlander C, Luger MF, Kammerlander-Knauer U, Gosch M. Mode of anesthesia, mortality and outcome in geriatric patients. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;47(2):110–124. doi: 10.1007/s00391-014-0611-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson VB, Jones RS. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin F, Chung F. Minimizing perioperative adverse events in the elderly. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87(4):608–624. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrest JB, Rehder K, Cahalan MK, Goldsmith CH. Multicenter study of general anesthesia. III. Predictors of severe perioperative adverse outcomes. Anesthesiology. 1992;76(1):3–15. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, Calkins H, Chaikof E, Fleischmann KE, Freeman WK, Froehlich JB, Kasper EK, Kersten JR, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (writing committee to revise the 2002 guidelines on Perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery): developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):e418–e499. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hackett NJ, De Oliveira GS, Jain UK, Kim JY. ASA class is a reliable independent predictor of medical complications and mortality following surgery. Int J Surg. 2015;18:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakobsson JG. Peer review report 2 on "ASA class is a reliable independent predictor of medical complications and mortality following surgery - an observational study". Int J Surg. 2015;13(Suppl 1):44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankar A, Johnson SR, Beattie WS, Tait G, Wijeysundera DN. Reliability of the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status scale in clinical practice. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(3):424–432. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao CC, Shen WW, Chang CC, Chang H, Chen TL. Surgical adverse outcomes in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 2013;257(3):433–438. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b9b25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin JA, Liao CC, Chang CC, Chang H, Chen TL. Postoperative adverse outcomes in intellectually disabled surgical patients: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu TC, Wang JO, Chau SW, Tsai SK, Wang JJ, Chen TL, Tsai YC, Ho ST. Survey of 11-year anesthesia-related mortality and analysis of its associated factors in Taiwan. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwanica. 2010;48(2):56–61. doi: 10.1016/S1875-4597(10)60014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson EJ, Forbes A. Introduction to propensity scores. Respirology. 2014;19(5):625–635. doi: 10.1111/resp.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang PY, Chien LN, Lin YF, Wu MS, Chiu WT, Chiou HY. Risk factors of gender for renal progression in patients with early chronic kidney disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(30):e4203. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deiner S, Westlake B, Dutton RP. Patterns of surgical care and complications in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):829–835. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung JY, Chang WY, Lin TW, Lu JR, Yang MW, Lin CC, Chang CJ, Chou AH. An analysis of surgical outcomes in patients aged 80 years and older. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwanica. 2014;52(4):153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KI, Park KH, Koo KH, Han HS, Kim CH. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict postoperative morbidity and mortality in elderly patients undergoing elective surgery. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(3):507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JY, Yoon SJ, Kim SW, Jung HW, Kim KI, Kang E, Kim SW, Han HS, Kim CH. Prediction of postoperative complications using multidimensional frailty score in older female cancer patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Class 1 or 2. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(3):652–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitlock EL, Feiner JR, Chen LL. Perioperative mortality, 2010 to 2014: a retrospective cohort study using the national anesthesia clinical outcomes registry. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(6):1312–1321. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visnjevac O, Davari-Farid S, Lee J, Pourafkari L, Arora P, Dosluoglu HH, Nader ND. The effect of adding functional classification to ASA status for predicting 30-day mortality. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(1):110–116. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Manach Y, Collins G, Rodseth R, Le Bihan-Benjamin C, Biccard B, Riou B, Devereaux PJ, Landais P. Preoperative score to predict postoperative mortality (POSPOM): derivation and validation. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(3):570–579. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu CY, Lin JT, Ho HJ, Su CW, Lee TY, Wang SY, Wu C, Wu JC. Association of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy with reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a nationwide cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(1):143–151. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kempen GI, Sanderman R, Miedema I, Meyboom-de Jong B, Ormel J. Functional decline after congestive heart failure and acute myocardial infarction and the impact of psychological attributes. A prospective study. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(4):439–450. doi: 10.1023/A:1008991522551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu PH, Lin YT, Lee TC, Lin MY, Kuo MC, Chiu YW, Hwang SJ, Chen HC. Predicting mortality of incident dialysis patients in Taiwan--a longitudinal population-based study. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen CP, Cheng TY, Tsai MK, Chang YC, Chan HT, Tsai SP, Chiang PH, Hsu CC, Sung PK, Hsu YH, et al. All-cause mortality attributable to chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study based on 462 293 adults in Taiwan. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2173–2182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramarapu S. Chronic kidney disease and postoperative morbidity associated with renal dysfunction after elective orthopedic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(3):700. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318245dd11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livhits M, Ko CY, Leonardi MJ, Zingmond DS, Gibbons MM, de Virgilio C. Risk of surgery following recent myocardial infarction. Ann Surg. 2011;253(5):857–864. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182125196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez-Perez A, Gaist D, Wallander MA, McFeat G, Garcia-Rodriguez LA. Mortality after hemorrhagic stroke: data from general practice (the health improvement network) Neurology. 2013;81(6):559–565. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829e6eff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan.