Abstract

Background

The presence of circulating cell-free DNA from tumours in blood (ctDNA) is of major importance to those interested in early cancer detection, as well as to those wishing to monitor tumour progression or diagnose the presence of activating mutations to guide treatment. In 2014, the UK Early Cancer Detection Consortium undertook a systematic mapping review of the literature to identify blood-based biomarkers with potential for the development of a non-invasive blood test for cancer screening, and which identified this as a major area of interest. This review builds on the mapping review to expand the ctDNA dataset to examine the best options for the detection of multiple cancer types.

Methods

The original mapping review was based on comprehensive searches of the electronic databases Medline, Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane library, and Biosis to obtain relevant literature on blood-based biomarkers for cancer detection in humans (PROSPERO no. CRD42014010827). The abstracts for each paper were reviewed to determine whether validation data were reported, and then examined in full. Publications concentrating on monitoring of disease burden or mutations were excluded.

Results

The search identified 94 ctDNA studies meeting the criteria for review. All but 5 studies examined one cancer type, with breast, colorectal and lung cancers representing 60% of studies. The size and design of the studies varied widely. Controls were included in 77% of publications. The largest study included 640 patients, but the median study size was 65 cases and 35 controls, and the bulk of studies (71%) included less than 100 patients. Studies either estimated cfDNA levels non-specifically or tested for cancer-specific mutations or methylation changes (the majority using PCR-based methods).

Conclusion

We have systematically reviewed ctDNA blood biomarkers for the early detection of cancer. Pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical considerations were identified which need to be addressed before such biomarkers enter clinical practice. The value of small studies with no comparison between methods, or even the inclusion of controls is highly questionable, and larger validation studies will be required before such methods can be considered for early cancer detection.

Keywords: cfDNA, ctDNA, Cancer, Detection, Diagnosis, Liquid biopsy

Background

The early detection of cancers before they metastasise to other organs allows definitive local treatment, resulting in excellent survival rates. This is particularly true for breast cancer, but also others, including lung and colorectal cancer [1]. Early detection and diagnosis has therefore been a major goal of cancer research for many years, and the concept of early detection from a blood sample has been the focus of considerable effort. However, to date no blood biomarkers have had sufficient sensitivity and specificity to warrant their clinical use for early cancer detection, and their potential remains unrealised [2]. Hanahan and Weinberg [3] identified the major biological attributes of cancer, and it is apparent that most if not all of these biological processes give rise to biomarkers present in blood [4]. Circulating cell free DNA produced from cancers is known as circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA), and represents a subset of the circulating DNA (cfDNA) normally present at low levels in the blood of healthy individuals.

Since the first description of circulating cfDNA in blood [5, 6], it has become clear that total ctDNA levels rise in a number of disorders in addition to cancer including myocardial infarction [7], serious infections, and inflammatory conditions [8], as well as pregnancy where it can be used for prenatal diagnosis [9]. The source of this DNA appears to be mainly the result of cell death – either by necrosis or apoptosis [5, 9–11]. A raised ctDNA level is therefore non-specific, but may indicate the presence of serious disease. In blood, ctDNA is always present as small fragments, which makes assay design challenging [12]. Nevertheless, many analytical methods are available to measure ctDNA, and the field is rapidly maturing to the point where it may be clinically relevant to many patients.

In 2014, the UK Early Cancer Detection Consortium (ECDC) conducted a rapid mapping review of blood biomarkers of potential interest for cancer screening [13], and identified 814 biomarkers, including 39 ctDNA biomarkers. This paper uses the list generated from the mapping review, updated with relevant publications published since its completion to discuss the candidacy of ctDNA markers for early detection of cancer.

Methods

Our mapping review [13] conducted comprehensive searches of the electronic databases Medline, Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane library, and Biosis to obtain relevant literature on blood-based biomarkers for cancer detection in humans (PROSPERO no. CRD42014010827). The search period finished in July 2014, therefore the searches have been updated to December 2016 using the same search terms. The abstracts of the publications retrieved were reviewed to identify those with validation data (usually indicated by case-control design) and to determine what ctDNA biomarkers had been measured in serum or plasma. Full details of the methods used are published elsewhere [13], and described briefly here. English language publications of any sample size were eligible and the full eligibility criteria used are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search criteria for ctDNA publications

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| English language studies | Studies published in non-English language |

| Studies within last seven years (2010–2016) | Studies published in 2009 or earlier |

| Controlled studies | Citation titles without abstracts |

| Validation Studies (comparison with controls) | Parallel publications and reviews based on the same or overlapping patient populationsa |

| Cancer detection/ diagnosis/screening | Prognosis or prediction (treatment response) associated markers |

| Biomarkers measured in blood plasma or serum (markers or biomarkers) |

Tissue, blood cells, or other bodily fluid samples |

| DNA (including cfDNA and ctDNA) | Abstracts of panels which do not state which biomarkers are studied |

| Human DNA | Viral and microbial DNA |

aReviews and meta-analyses are cited, but not considered as evidence, but studies were included if they appeared to contain new data

The search strategy was deliberately inclusive, using keywords and subject headings as follows, to provide a comprehensive list of those ctDNA candidate biomarkers that had been used to identify cancers from blood samples. The search terms included ‘cancer’ ‘diagnosis’, ‘markers’, ‘blood’, and ‘screening’ with ‘DNA’, ‘cfDNA’, or ‘ctDNA’. Keywords and subject headings were determined by members of the ECDC working with the review team at the University of Sheffield. The results of the searches were collated in an Endnote database and results tabulated, with references, size of study, and methods used. To avoid bias, two reviewers conducted screening; references identified by either as relevant were included for further inspection. Those featuring ctDNA with data related to diagnosis or detection of three or more types of cancer were identified and retained for closer scrutiny to determine their potential utility.

Results

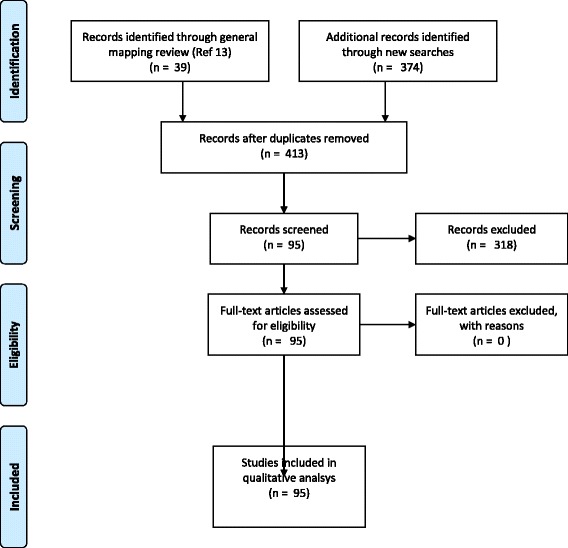

Following the updated searches and study selection, a total of 84 ctDNA markers were identified from 94 individual publications (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Individually identified markers with detection ability in ctDNA

| No | Biomarker | Acronym | Cancer | DNA alteration | Assay type (qPCR, ddPCR, BEAMing, NGS, Other) | Size Cases (controls) | Plasma or Serum | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14–3-3 sigma | 14–3-3 s | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 106 (74) | Serum | [48] |

| 2 | absent in melanoma 1 | AIM1; Beta/gamma crystallin domain-containing protein 1 | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 76 (30) | Serum | [62] |

| 3 | ADAM: metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 | ADAMTS1 | Pancreatic | Methylation | qPCR | 42 | Serum | [63] |

| 4 | Adenomatous Polyposis Coli | APC | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 76 (30) | Serum | [62] |

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 33 (10) | Plasma | [64] | |||

| Testicular | Methylation | qPCR | 73 (35) | Serum | [47] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 191 | Plasma | [65] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 33 | Serum | [53] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | PCR | 104 | Serum | [66] | |||

| Ovarian | Methylation | qPCR | 87 (62) | Serum | [67] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] | |||

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] | |||

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 110 (50) | Plasma | [70] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | qPCR | 27 (15) | Plasma | [71] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | PCR | 60 (100) | Plasma | [72] | |||

| 5 | ALU repeat | Alu 115 bp | Breast | NA | qPCR | 39 (49) | Plasma | [22] |

| Alu 247 bp | Pancreatic | NA | qPCR | 73 (43) | Plasma | [73] | ||

| CRC | NA | qPCR | 50 (35) | Plasma | [20] | |||

| Breast | NA | qPCR | 293 (100) | Plasma | [19] | |||

| Thyroid | NA | qPCR | 176 (19) | Plasma | [24] | |||

| CRC | NA | qPCR | 104 (173) | Serum | [23] | |||

| 6 | basonuclin 1 | BNC1 | Pancreatic | Methylation | qPCR | 42 | Serum | [63] |

| 7 | BIN1 | BIN1 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 76 (30) | Serum | [62] |

| 8 | BLU | BLU | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 63 (36) | Plasma | [74] |

| 9 | BRAF | BRAF (V600E) | Melanoma | Mutation | qPCR | 221 | Both | [17] |

| Lung | Mutation | NGS | 68 (107) | Plasma | [75] | |||

| LCH | Mutation | qPCR | 30 | Plasma | [76] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 106 | Plasma | [77] | |||

| Thyroid | Mutation | qPCR | 77 | Plasma | [78] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | BEAMing | 503 | Plasma | [21] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 191 | Plasma | [65] | |||

| 10 | BRCA1 | BRCA1 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 89 | Serum | [79] |

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] | |||

| Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 50 | Serum | [80] | |||

| Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 33 (33) | Plasma | [81] | |||

| 11 | CALCA | CALCA | Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [82] |

| 12 | CDH1 | CDH1 | Ovarian | Methylation | qPCR | 87 (62) | Serum | [67] |

| 13 | CDH13 | CDH13 | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 63 (36) | Plasma | [74] |

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 110 (50) | Plasma | [70] | |||

| 14 | CDO1 | CDO1 | Various | Methylation | qPCR | 150 (60) | Plasma | [83] |

| 15 | CHD1 | CHD1 | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 76 (30) | Serum | [62] |

| 16 | CST6 | CST6 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 196 (37) | Plasma | [84] |

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] | |||

| 17 | CHRM2 | CHRM2 | Gastric | Methylation | qPCR | 58 (30) | Serum | [85] |

| 18 | CYCD2 | CYCD2 | CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] |

| 19 | DAPK1 | DAPK1 | HNSCC | Methylation | PCR | 40 (41) | Serum | [87] |

| 20 | DCC | DCC | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 76 (30) | Serum | [62] |

| 21 | DCLK1 | DCLK1 | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 65 (95) | Plasma | [88] |

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 32 (8) | Plasma | [89] | |||

| 22 | DKK3 | DKK3 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 604 (59) | Serum | [90] |

| 23 | DLEC1 | DLEC1 | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 110 (50) | Plasma | [70] |

| HNSCC | Methylation | PCR | 40 (41) | Serum | [87] | |||

| 24 | DNA (NOS) | DNA | Lung | NA | qPCR v Seq | 30 (26) | Plasma | [91] |

| Various | No | NGS | 77 (35) | Plasma | [45] | |||

| Various | No | NGS | 640 | Plasma | [16] | |||

| Lung | No | qPCR | 65 (44) | Plasma | [92] | |||

| Ovarian | No | bDNA | 36 (41) | Serum | [93] | |||

| 25 | e-cadherin | e-cadherin | Colorectal | Methylation | PCR | 60 (100) | Plasma | [72] |

| 26 | EGFR | EGFR | Lung | Mutation | NGS | 68 (107) | Plasma | [75] |

| 27 | EP300 | EP300 | Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [82] |

| 28 | ERBB2 | HER2 | Lung | Mutation | NGS | 68 (107) | Plasma | [75] |

| Breast | Amplification | qPCR | 120 (98) | Plasma | [14] | |||

| Oesphageal | Amplification | qPCR | 41 (34) | Plasma | [94] | |||

| 29 | ESR | ESR | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 106 (74) | Serum | [48] |

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] | |||

| 30 | FAM5C | FAM5C | Gastric | Methylation | qPCR | 58 (30) | Serum | [85] |

| 31 | FHIT | FHIT | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 63 (36) | Plasma | [74] |

| Renal | Methylation | qPCR | 27 (15) | Plasma | [71] | |||

| 32 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Breast | NA | qPCR | 200 (100) | Serum | [26] |

| Breast | NA | qPCR | 33 (50) | Serum | [27] | |||

| Breast | NA | qPCR | 27 (32) | Serum | [28] | |||

| Breast | NA | qPCR | 33 (32) | Serum | [29] | |||

| 33 | GNA11 | GNA11 | Uveal Melanoma | Mutation | NGS | 28 | Plasma | [34] |

| 34 | GNAQ | GNAQ | Uveal Melanoma | Mutation | NGS | 28 | Plasma | [34] |

| 35 | GPC3 | GPC3 | Pancreatic | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] |

| 36 | GSTP1 | GSTP1 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 89 | Serum | [79] |

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] | |||

| Prostate | Methylation | PCR | 12 (10) | Plasma | [95] | |||

| Prostate | Methylation | qPCR | 31 (44) | Plasma | [96] | |||

| Testicular | Methylation | qPCR | 73 (35) | Serum | [47] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] | |||

| Prostate | Methylation | PCR | 31 (34) | Serum | [97] | |||

| 37 | HIC1 | HIC1 | CRC | Methylation | PCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [98] |

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] | |||

| 38 | HOXA7 | HOXA7 | Various | Methylation | qPCR | 150 (60) | Plasma | [83] |

| 39 | HOXA9 | HOXA9 | Various | Methylation | qPCR | 150 (60) | Plasma | [83] |

| 40 | HOXD13 | HOXD13 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 253 (434) | Serum | [99] |

| 41 | IgH | FR3A/VLJH | Lymphoma | Clonality | NGS | 75 | Plasma | [43] |

| 42 | ITIH5 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 604 (59) | Serum | [90] | |

| 43 | INK4A | INK4A | HCC | Methylation | Seq | 66 (43) | Plasma | [100] |

| 44 | KLK10 | KLK10 | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 110 (50) | Plasma | [70] |

| 45 | KRAS | KRAS | Lung | Mutation | NGS | 68 (107) | Plasma | [75] |

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 52 | Plasma | [101] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 35 (135) | Plasma | [30] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 229 (100) | Plasma | [102] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 106 | Plasma | [77] | |||

| Lung | Mutation | qPCR | 82 (11) | Plasma | [103] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | BEAMing | 503 | Plasma | [21] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 191 | Plasma | [65] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | PCR | 104 | Serum | [66] | |||

| 46 | LINE1 Repeat | LINE1 79 bp | CRC | NA | qPCR | 50 (35) | Plasma | [20] |

| LINE1 300 bp | CRC | NA | qPCR | 503 | Plasma | [21] | ||

| Breast | NA | qPCR | 293 (100) | Plasma | [19] | |||

| 47 | MDG1 | MDG1 | CRC | Methylation | PCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [98] |

| 48 | Microsatellite alterations | FHIT LoH | Lung | NA | PCR | 87 (14) | Plasma | [104] |

| FHIT LoH | Lung | NA | PCR | 32 (10) | Serum | [105] | ||

| LoH | Oesophageal | NA | PCR | 18 (22) | Plasma | [106] | ||

| LoH | CRC | NA | qPCR | 33 | Serum | [53] | ||

| 3p LoH | Lung | NA | qPCR | 64 | Plasma | [107] | ||

| 49 | mitochondrial DNA | mtDNA | Breast | NA | qPCR | 60 (51) | Plasma | [108] |

| 50 | MLH1 | hMLH1 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 253 (434) | Serum | [99] |

| 51 | MYC | MYC | Neuroblastoma | Amplification | ddPCR | 44 | Plasma | [42] |

| 52 | MYF3 | MYF3 | Pancreatic | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] |

| 53 | MYLK | MYLK | Gastric | Methylation | qPCR | 58 (30) | Serum | [85] |

| 54 | O(6)-methyl-guanine-DNA methyltransferase | MGMT | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 76 | Serum | [62] |

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 33 | Serum | [53] | |||

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 89 | Serum | [79] | |||

| 55 | OPCML | OPCML | Ovarian | Methylation | qPCR | 87 (62) | Serum | [67] |

| 56 | P14 ARF tumor suppressor protein gene | P14 | Testicular | Methylation | qPCR | 73 (35) | Serum | [47] |

| Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] | |||

| 57 | P16 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | P16, CDKN2A | Testicular | Methylation | qPCR | 73 (35) | Serum | [47] |

| Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] | |||

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] | |||

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 63 (36) | Plasma | [74] | |||

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 253 (434) | Serum | [99] | |||

| HNSCC | Methylation | qPCR | 40 (41) | Serum | [87] | |||

| 58 | P21 | P21 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] |

| 59 | P53 | Various | Mutation | qPCR | 20 (16) | Plasma | [109] | |

| Various | NA | qPCR | 120 (120) | Plasma | [110] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 191 | Plasma | [65] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | PCR | 104 | Serum | [66] | |||

| SCLC | Mutation | qPCR | 51 (123) | Plasma | [55] | |||

| 60 | PCDHGB7 | PCDHGB7 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 253 (434) | Serum | [99] |

| 61 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A | cyclophilin A, gCYC, PPIA | CRC | NA | qPCR | 229 (100) | Plasma | [102] |

| 62 | PIK3CA | PIK3CA | Breast | Mutation | qPCR | 76 | Both | [18] |

| Lung | Mutation | NGS | 68 (107) | Plasma | [75] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | BEAMing | 503 | Plasma | [21] | |||

| CRC | Mutation | qPCR | 191 | Plasma | [65] | |||

| 63 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxid synthase 2 | PTGS2 | Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] |

| Testicular | Methylation | qPCR | 73 (35) | Serum | [47] | |||

| 64 | Protocadherin 10 | PCDH10 | CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 67 | Plasma | [111] |

| 65 | Retinoid-acid-receptor-beta gene | RARbeta2 | Breast | Methylation | PCR | 20 (25) | Plasma | [112] |

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 33 | Serum | [53] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] | |||

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 63 (36) | Plasma | [74] | |||

| 66 | RASSF1A | RASSF1A | Breast | Methylation | PCR | 93 (76) | Plasma | [113] |

| Breast | Methylation | PCR | 20 (25) | Plasma | [112] | |||

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 39 (49) | Plasma | [22] | |||

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 604 (59) | Serum | [90] | |||

| Melanoma | Methylation | qPCR | 84 (68) | Plasma | [114] | |||

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 76 (30) | Serum | [62] | |||

| Testicular | Methylation | qPCR | 73 (35) | Serum | [47] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 33 | Serum | [53] | |||

| Ovarian | Methylation | qPCR | 87 (62) | Serum | [67] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] | |||

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 63 (36) | Plasma | [74] | |||

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 110 (50) | Plasma | [70] | |||

| HCC | Methylation | PCR | 40 (20) | Serum | [115, 116] | |||

| HCC | Methylation | PCR | 50 (50) | Serum | [117] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | PCR | 27 (15) | Plasma | [71] | |||

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 253 (434) | Serum | [99] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | PCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [98] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | qPCR | 157 (43) | Serum | [118] | |||

| Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 50 | Serum | [80] | |||

| Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [82] | |||

| 67 | RUNX3 | RUNX3 | Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 87 (62) | Serum | [67] |

| 68 | Septin 9 | Septin 9 | CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 97 (172) | Plasma | [119] |

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 378 (285) | Plasma | [120] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 60 (24) | Plasma | [121] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 55 (1457) | Plasma | [58] | |||

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 70 (100) | Plasma | [122] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 135 (341) | Plasma | [123] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 50 (94) | Plasma | [124] | |||

| CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 44 (444) | Plasma | [59] | |||

| 69 | SFN | SFN | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 253 (434) | Serum | [99] |

| 70 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 | Ovarian | Methylation | qPCR | 87 (62) | Serum | [67] |

| 71 | SHOX2 | SHOX2 | Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 188 (155) | Plasma | [125] |

| Lung | Methylation | qPCR | 118 (212 | Plasma | [126] | |||

| 72 | SOX17 | SOX17 | Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 114 (60) | Plasma | [127] |

| Various | Methylation | qPCR | 150(60) | Plasma | [83] | |||

| 73 | SLC26A4 | SLC26A4 | Thyroid | Methylation | qPCR | 176 (19) | Plasma | [24] |

| 74 | SLC5A8 | SLC5A8 SLC26A4 | Thyroid | Methylation | qPCR | 176 (19) | Plasma | [24] |

| 75 | SRBC | SRBC | Pancreatic | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] |

| 76 | TAC1 | TAC1 | Various | Methylation | qPCR | 150 (60) | Plasma | [83] |

| 77 | human telomerase reverse transcriptase DNA | hTERT | CRC | NA | qPCR | 35 (135) | Plasma | [30] |

| HCC | NA | qPCR | 70 (30) | Plasma | [31] | |||

| HCC | NA | qPCR | 60 (29) | Plasma | [32] | |||

| HNSCC | NA | qPCR | 200 | Plasma | [33] | |||

| 78 | TFPI2 | TFPI2 | Ovarian | Methylation | PCR | 87 (62) | Serum | [67] |

| 79 | THBD-M | THBD-M | CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 107 (98) | Plasma & Serum | [128] |

| 80 | TIMP3 | TIMP3 | Renal | Methylation | PCR | 35 (54) | Serum | [68] |

| Breast | Methylation | qPCR | 36 (30) | Plasma | [69] | |||

| 81 | TMS | TMS | Pancreatic | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] |

| 82 | UCHL1 | UCHL1 | HNSCC | Methylation | PCR | 40 (41) | Serum | [87] |

| 83 | Von Hippel Lindau gene | VHL | CRC | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] |

| Pancreatic | Methylation | qPCR | 30 (30) | Plasma | [86] | |||

| Renal | Methylation | qPCR | 157 (43) | Serum | [118] | |||

| 84 | ZFP42 | ZFP42 | Various | Methylation | qPCR | 150 (60) | Plasma | [83] |

CRC colorectal cancer, HNSCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, LCH Langerhans cell histocytosis, SCLC small cell lung cancer

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram

The ctDNA biomarkers divided naturally into two groups:

-

I.

those with potential specificity for neoplasia (ctDNA - usually mutations or DNA alterations such as methylation), and

-

II.

those designed to measure DNA levels, which may not be specific to neoplasia.

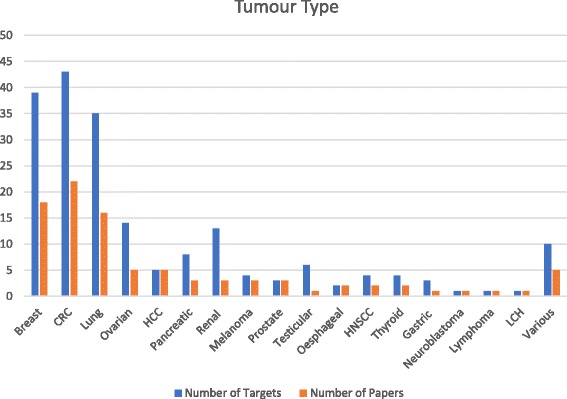

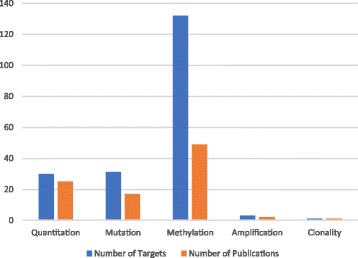

Figure 2 shows the distribution of studies by cancer type, including two publications on amplification [12, 14], and one on clonality [15]. One of the amplification papers looked at HER2 [14], while the other examined multiple targets by NGS [12].

Fig. 2.

Number of targets and publications by tumour type, showing the expected concentration of studies on common cancer types. CRC, colorectal cancer; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma

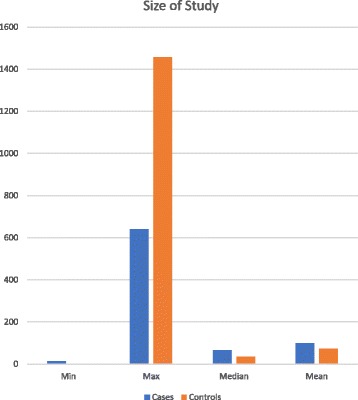

Of the 94 publications included, 72 publications (77%) were case-control design diagnostic validation studies, and 22 were case series. The size and design of the studies varied widely. The largest study included 640 cancer patients [16]. The median study size was 65 cases, with a mean of 98 cases (range 12–640 cancer patients), indicating that the bulk of studies (67/94, 71%) included <100 patients (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Study size. There are occasional large studies, but the vast majority are small, evidenced by the low median and averages for both cases and controls

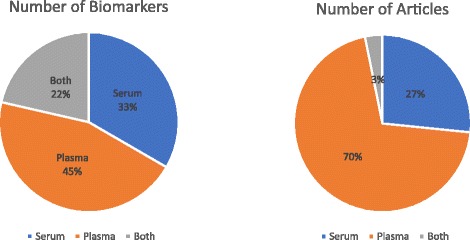

Most publications were focussed on ctDNA in plasma (n = 67) rather than serum (n = 25) with 2 comparing both. Plasma was used for 38 markers, and serum for 28 markers, and either for 18 markers (Fig. 4). Two comparative studies of serum and plasma were conducted: one for BRAF mutations, and the other for PIK3CA mutations [17, 18].

Fig. 4.

Use of serum or plasma for studies. The majority use plasma, but serum is preferred for methylation studies by some. Only three studies looked at both serum and plasma

The target of ctDNA studies and the methods used to measure these targets varied considerably (Figs. 5 and 6 respectively). Non-specific total ctDNA levels (quantitation) were usually estimated by size distribution assays based on repeats: LINE1, and ALU were used in 3 [19–21] and 6 publications respectively [20–25]. However, some single genes were also used to measure DNA levels – particularly GAPDH in a series of 4 publications on breast cancer [26–29], and hTERT in 4 publications [30–33]. The majority of publications examined gene methylation markers (n = 49), though most examined methylation of multiple target genes for a particular tumour type (Fig. 5). Genes commonly mutated in cancer were also markers of interest, namely APC, BRAF, EGFR, HER2, GNAQ, GNA11, KRAS, P53, and PIK3CA. Only one gene, APC, was studied for both methylation and mutation. Few markers were used to identify particular tumour types, but some are particularly likely to occur in certain tumour types. GNAQ and GNA11 mutations have been identified in the plasma of uveal melanoma patients and are rare in other tumour types [34]. Other mutations are not tumour type-specific, and mutations in 6 of the 9 genes listed above were reported in multiple tumour types.

Fig. 5.

Targets: many studies looked at multiple targets, mainly either mutations or methylated genes

Fig. 6.

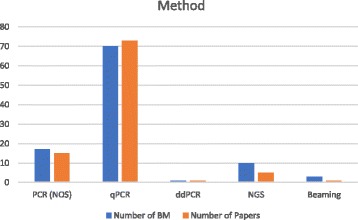

Choice of method. Most publications used just one method, but biomarkers were measurable by more than one assay in 6 instances

Discussion

The number of publications on ctDNA is increasing rapidly [35, 36], and a recent review emphasises the potential of the field [37]. Most (71%) are small case control studies with less than 100 patients, and in our view very few studies meet the requirements of analytical validation allowing their use within accredited (ISO:15,189) clinical laboratories, though some may have unpublished commercially-held analytical validation data. The stage and size of the tumours included is variable, and few studies are large enough to give robust subgroup assessments. Larger tumours produce more ctDNA, though tumour type also has an impact [16]. The value of small studies with no comparison between methods, or even the inclusion of controls is highly questionable. Most include a statement that ‘larger studies are required’, but larger trials rarely result due to the necessary cost implications. Unless well-designed prospective studies based on sample size calculations are performed, there is little likelihood of such methods reaching clinical practice for the detection of cancer at an early stage. There is also a likelihood of bias in that negative results for these markers are rarely if ever reported, and unlike clinical trials, there is no requirement for the registration of diagnostic validation studies. The use of ctDNA for early cancer detection comes under existing molecular pathology guidance, which emphasises the requirements for careful pre-analytical preparation, analysis, and reporting of results [38]. It is important that studies adhere to the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidance [39], and regional guidance (e.g. US Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA); UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)). It is hardly surprising then that, to date, no ctDNA markers have made it into screening programmes, due in part to the economic feasibility of completing the necessary stages of validation [40]. Nevertheless, there is encouraging evidence that ctDNA can be used to detect cancers of many types [16], and the poor quality of many studies should not detract from this fact.

A plethora of methods are available for ctDNA measurement, which have been well reviewed elsewhere [41]. BEAMing, PCR clamping methods, and deep sequencing using NGS are now the most commonly used [42, 43] and are widely regarded as the most sensitive methods currently available. A recent report of copy number variation (CNV) in breast cancer is not surprising given the ability of this method to detect such changes in pregnancy [15]. However, it should be noted that many of these methods are expensive. The development of highly sensitive NGS methods for ctDNA may prove necessary to obtain the best results [44], but large blood samples (> 10 ml may be needed as the number of DNA molecules present in small samples is often low) [45]. This may be at odds with the key requirement of cost effectiveness for screening programmes, and in our view this represents a real challenge for ctDNA. The problem is probably not insuperable if automation allows the integration of such methods into large blood sciences laboratories, but this is not as yet the case.

As ctDNA is composed largely of short fragments, short amplicons are required for maximum sensitivity of PCR reactions, particularly if mutations are being detected [46]. This is compounded by DNA loss in some reactions, particularly bisulphite modification of DNA, and it may be preferable to use nuclease protection assays [47, 48]. Methylation of key genes involved in carcinogenesis can be found in ctDNA, and has been studied by many groups, but it should be noted that substantial numbers of normal controls also have methylation of ctDNA for these genes [49].

It is clear that high sensitivity methods will be needed if ctDNA is to be used for early cancer detection. Several factors affect the sensitivity of ctDNA measurement. The first is the extraction method, and there are as yet too few studies which have compared the different options available, which now include automated instruments as well as manual extraction systems [50, 51]. The proportion of tumour derived DNA (ctDNA) in total cfDNA is greater in plasma than serum, and the higher ctDNA levels in serum are due to leakage from leukocytes during clotting [17]. The dilution effect for ctDNA in serum results in a reduced ability to detect mutations, particularly by methods with low analytical sensitivity [50]. Most groups working in the field realise this, and the majority of publications now look at plasma rather than serum.

Several publications were noteworthy, including one influential study which did not include healthy controls [16]. However, the comparison of DNA levels and multiple mutations in plasma from many different tumours types is helpful [44], and makes it clear that some tumours (e.g. gliomas) do not have high ctDNA levels in plasma, as previously found when comparing CSF with plasma [52]. This is also one of several publications that examines early stage disease, and shows that patients with localised disease have lower ctDNA levels [16]. Few publications have examined the ability of ctDNA to detect smaller tumours, though all agree that ctDNA levels increase as tumours enlarge [42].

Choice of target also influences results: the use of LINE1 and ALU repeats allows quantitative size distribution of DNA to be measured. Several publications suggest that this can distinguish cancer, and even pre-cancerous conditions from controls [30]. The size distribution of CRC appears to be different from other tumours due to first pass hepatic metabolism [20, 53]. Absolute quantitation by single gene methods such as GAPDH or hTERT will result in lower estimates of DNA content, and it is likely that this is due to the higher sensitivity of the ALU and LINE1 assays [30].

The use of mutations common within cancers is attractive, and the use of ctDNA to provide companion diagnostic information in patients in whom biopsy material is not available is now entering practice [54]. However, it should be noted that such mutations in P53 can occur in the blood of healthy controls, and could give rise to substantial numbers of false positive results [55].

Septin 9 methylation is often regarded as a model for future work [56, 57], and it is notable that there are some large studies [58] within the evidence base for the use of this marker in colorectal cancer, often used in addition to other markers, such as faecal occult blood testing (FoBT) or faecal immunohistochemical testing (FIT). Pre-analytical factors have been examined for this marker [59], including diurnal variation [60]. Plasma methylation of Septin 9 is now available as a commercial test (Epi proColon 2.0; Epigenomics AG, Berlin, Germany) which has recently obtained FDA approval for colorectal cancer screening (April 2016). This is the first blood test to be approved for cancer screening, and represents an encouraging milestone.

Other methylation targets have been studied in depth and show considerable promise. These include APC for colorectal cancer, with a large number of studies (Table 2), and SHOX3, for which a recent meta-analysis suggests that it could have an important role in the diagnosis of lung cancer [61].

There is an encouraging trend towards larger, more ambitious studies, supported by the commercial sector (e.g. (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02889978, and https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03085888). Case control studies (particular retrospective ones) can give biased results, and prospective studies in at-risk cohorts would be more useful in examining the predictive capability of these markers. Such prospective studies should include controls proven not to have cancer. The comparison of new with existing methods (e.g. tumour markers, radiology), and competing technologies, is recommended, and often required by regulators. This has cost implications for funding bodies, but is essential if the field is to progress rapidly.

Conclusions

While ctDNA analysis may provide a viable option for the early detection of cancers, not all cancers are detectable using current methods. However, improvements in technology are rapidly overcoming some of the issues of analytical sensitivity, and it is likely that mutation and methylation analysis of ctDNA will improve specificity for the diagnosis of cancer.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the wider Early Cancer Detection Consortium for their assistance in putting together this paper, and for the many discussions which underpin it. Patient and Public representatives were involved in this work.

Funding

This work was conducted on behalf of the Early Cancer Detection Consortium, within the programme of work for work packages & 2. The Early Cancer Detection Consortium is funded by Cancer Research UK under grant number: C50028/A18554. It was subsequently supported by an unrestricted educational grant from PinPoint Cancer Ltd. (www.pinpointcancer.co.uk), following cessation of the grant in 2016. Neither of the two funding bodies had any input or influence over the design, study, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Availability of data and materials

The papers quoted are publically available from the publishers, and many are now open access.

Abbreviations

- 14–3-3 s

14–3-3 sigma or tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein theta

- ADAM

metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1

- AIM1

absent in melanoma 1

- ALU

Alu repeat/element 9e

- APC

Adenomatous Polyposis Coli

- ARF

alternate reading frame

- BIN1

bridging integrator 1

- BLU

zinc finger MYND-type containing 10

- BM

biomarker

- BNC1

basonuclin 1

- bp

base pair

- BRAF

B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase

- BRCA1

breast cancer 1, DNA repair associated

- BRINP3

BMP/Retinoic Acid Inducible Neural Specific 3

- CALCA

calcitonin related polypeptide alpha

- CDH1

cadherin 1

- CDH13

cadherin 13

- CDO1

cysteine dioxygenase type 1

- cfDNA

circulating cell-free DNA

- CHD1

chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 1

- CHRM2

cholinergic receptor muscarinic 2

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CLSI

Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute

- CRC

colorectal carcinoma

- CST6

cystatin 6

- ctDNA

circulating tumour DNA

- CYCD2

cyclin D2

- DAPK1

death-associated protein kinase 1

- DCC

DCC Netrin 1 receptor

- DCLK1

doublecortin like kinase 1

- ddPCR

digital droplet polymerase chain reaction

- DKK3

Dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 3

- DLEC1

deleted in lung and esophageal cancer 1

- DNA

dexoxyribonucleic acid

- ECDC

UK Early Cancer Detection Consortium

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1)

- EP300

E1A binding protein P300

- ERBB2

erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (HER2)

- ESR

estrogen receptor 1

- FAM5C

BMP/retinoic acid inducible neural specific 3 (BRINP3)

- FDA

US Food and Drug Adminstration

- FHIT

fragile histidine triad

- FIT

faecal immunohistochemical testing

- FoBT

faecal occult blood testing

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- gCYC

cyclophilin A

- GNA11

G protein subunit alpha 11

- GNAQ

G protein subunit alpha Q

- GPC3

glypican 3

- GSTP1

glutathione S-transferase pi 1

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HER1

human epidermal growth factor receptor 1

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HIC1

HIC ZBTB transcriptional repressor 1

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HOXA7

Homeobox A7

- HOXA9

Homeobox A9

- HOXD13

Homeobox D13

- hTERT

human telomerase reverse transcriptase DNA

- IgH

immunoglobulin heavy locus

- INK4A

cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A/P16)

- ISO

International Standards Organization

- ITIH5

inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain family member 5

- KLK10

kallikrein related peptidase 10

- KRAS

KRAS Proto-Oncogene, GTPase

- LCH

Langerhans cell histocytosis

- LINE1

long interspersed nuclear element 1

- LoH

loss of heterozygosity

- Max

maximum

- MDG1

microvascular endothelial differentiation gene 1

- MGMT

O(6)-methyl-guanine-DNA methyltransferase

- Min

minimum

- MLH1

MutL Homolog 1

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- MYC

MYC proto-oncogene

- MYF3

myogenic differentiation 1 (MYOD1)

- MYLK

myosin light chain kinase

- NGS

next generation sequencing

- NICE

UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NOS

not otherwise specified

- OPCML

opioid binding protein/cell adhesion molecule like

- P14

P14 ARF tumor suppressor protein gene

- P16

P16 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A)

- P21

cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A

- P53

tumor protein P53

- PCDH10

Protocadherin 10

- PCDHGB7

protocadherin gamma subfamily B7

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PIK3CA

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha

- PPIA

Peptidylprolyl isomerase A

- PTGS2

Prostaglandin-endoperoxid synthase 2

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RARbeta2

Retinoid-acid-receptor-beta gene

- RASSF1A

Ras association domain family member 1

- RUNX3

runt related transcription factor 3

- SFN

Stratifin

- SFRP5

secreted frizzled related protein 5

- SHOX2

short stature homeobox 2

- SLC26A4

solute carrier family 26 member 4

- SLC5A8

solute carrier family 5 member 8

- SOX17

SRY-Box 17

- SRBC

serum deprivation response factor-related gene

- STARD

Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

- TAC1

tachykinin precursor 1

- TFPI2

tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2

- THBD-M

thrombomodulin

- TIMP3

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3

- TMS

tumor differentially expressed protein 1

- UCHL1

Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase L1

- V600E

Mutation resulting in an amino acid substitution at position 600 in BRAF, from a valine (V) to a glutamic acid (E)

- VHL

Von Hippel Lindau gene

- ZFP42

ZFP42 Zinc Finger Protein

Authors’ contributions

IC, SH, BW, and STP designed the study. Searches were performed by HBW. LU and HBW performed the mapping review with input from the ECDC. HK and IC scanned the resulting publications relating to ctDNA. The draft manuscript was prepared by IC with input fom MM, AC, DT, OS, AR, HK, HBW, BW and JS. All authors agreed the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

IC is a pathologist and has recently moved to a post with the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organisation in Lyon. LU, and SH are Research Fellows in systematic review and HBW is an Information Specialist working at the University of Sheffield, UK. HK is a scientist and PhD student working on early cancer detection. AR is a Lecturer in Biomedical Science working at Coventry University, UK. STP is an associate professor with a NIHR Career Development Fellowship using quantitative research methods to assess new screening programmes. MM is a healthcare scientist at the University of Leeds with expertise in biomarker and in vitro diagnostic (IVD) development, validation and clinical evaluation. AC is Professor of Cancer Genetic Epidemiology at the University of Sheffield, UK. DT is Reader in Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Sheffield, UK. OS is Director of the Trinity Translational Medicine Institute (TTMI) and Professor in Molecular Pathology at Trinity College Dublin, Eire. JS is Professor of Translational Cancer Genetics at Leicester University, UK, with a particular interest in cfDNA.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The ECDC has grant funding for early cancer biomarker research from Cancer Research UK who funded this work. The ECDC involves several companies as follows: GE Healthcare, Life Technologies, NALIA Systems Ltd., and Perkin-Elmer. Individual ECDC members have declared their interests to the ECDC secretariat. IC was formerly chairman and CEO of PinPoint Cancer Ltd., a spin-out company from ECDC which in part funded the completion of this work though provision of staff time (IC). MM is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Diagnostic Evidence Co-operative Leeds. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the UK Department of Health.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ian A. Cree, Email: creei@iarc.fr

Lesley Uttley, Email: l.uttley@sheffield.ac.uk.

Helen Buckley Woods, Email: h.b.woods@sheffield.ac.uk.

Hugh Kikuchi, Email: H.Kikuchi@warwick.ac.uk.

Anne Reiman, Email: annereiman01@gmail.com.

Susan Harnan, Email: s.harnan@sheffield.ac.uk.

Becky L. Whiteman, Email: ab5190@coventry.ac.uk

Sian Taylor Philips, Email: S.Taylor-Phillips@warwick.ac.uk.

Michael Messenger, Email: M.P.Messenger@leeds.ac.uk.

Angela Cox, Email: a.cox@sheffield.ac.uk.

Dawn Teare, Email: m.d.teare@sheffield.ac.uk.

Orla Sheils, Email: OSHEILS@tcd.ie.

Jacqui Shaw, Email: js39@leicester.ac.uk.

References

- 1.McPhail S, et al. Stage at diagnosis and early mortality from cancer in England. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 Suppl 1:S108–S115. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffy MJ. Tumor markers in clinical practice: a review focusing on common solid cancers. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(1):4–11. doi: 10.1159/000338393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cree IA. Improved blood tests for cancer screening: general or specific? BMC Cancer. 2011;11:499. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo YM, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–487. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson PJ, Lo YM. Plasma nucleic acids in the diagnosis and management of malignant disease. Clin Chem. 2002;48(8):1186–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lou X, et al. A novel Alu-based real-time PCR method for the quantitative detection of plasma circulating cell-free DNA: sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35(1):72–80. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swarup V, Rajeswari MR. Circulating (cell-free) nucleic acids--a promising, non-invasive tool for early detection of several human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(5):795–799. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo YM. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis: from dream to reality. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):32–37. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.223024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zonta E, Nizard P, Taly V. Assessment of DNA integrity, applications for cancer research. Adv Clin Chem. 2015;70:197–246. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo YM, et al. Maternal plasma DNA sequencing reveals the genome-wide genetic and mutational profile of the fetus. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(61):61ra91. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heitzer E, et al. Establishment of tumor-specific copy number alterations from plasma DNA of patients with cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(2):346–356. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uttley L, et al. Building the evidence base of blood-based biomarkers for early detection of cancer: a rapid systematic mapping review. EBioMedicine. 2016;10:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page K, et al. Detection of HER2 amplification in circulating free DNA in patients with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(8):1342–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirkizlar E, et al. Detection of clonal and subclonal copy-number variants in cell-free DNA from patients with breast cancer using a massively multiplexed PCR methodology. Transl Oncol. 2015;8(5):407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bettegowda C, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aung KL, et al. Analytical validation of BRAF mutation testing from circulating free DNA using the amplification refractory mutation testing system. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16(3):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Board, R.E., et al., Detection of PIK3CA mutations in circulating free DNA in patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2010. 120(2): p. 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Madhavan D, et al. Plasma DNA integrity as a biomarker for primary and metastatic breast cancer and potential marker for early diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146(1):163–174. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2946-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mead R, et al. Circulating tumour markers can define patients with normal colons, benign polyps, and cancers. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(2):239–245. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabernero J, et al. Analysis of circulating DNA and protein biomarkers to predict the clinical activity of regorafenib and assess prognosis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective, exploratory analysis of the CORRECT trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):937–948. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00138-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agostini M, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA: a promising marker of regional lymphonode metastasis in breast cancer patients. Cancer Biomark. 2012;11(2–3):89–98. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2012-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao TB, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA in serum as a biomarker for diagnosis and prognostic prediction of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(8):1482–1489. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zane M, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA, SLC5A8 and SLC26A4 hypermethylation, BRAF(V600E): a non-invasive tool panel for early detection of thyroid cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2013;67(8):723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikora K, et al. Evaluation of cell-free DNA as a biomarker for pancreatic malignancies. Int J Biol Markers. 2014:e136–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Gong B, et al. Cell-free DNA in blood is a potential diagnostic biomarker of breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2012;3(4):897–900. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong XY, et al. Elevated level of cell-free plasma DNA is associated with breast cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276(4):327–331. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seefeld M, et al. Parallel assessment of circulatory cell-free DNA by PCR and nucleosomes by ELISA in breast tumors. Int J Biol Markers. 2008;23(2):69–73. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2008.3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanetti-Dallenbach RA, et al. Levels of circulating cell-free serum DNA in benign and malignant breast lesions. Int J Biol Markers. 2007;22(2):95–99. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2008.4546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrone F, et al. Circulating free DNA in a screening program for early colorectal cancer detection. Tumori. 2014;100(2):115–121. doi: 10.1177/030089161410000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Divella R, et al. PAI-1, t-PA and circulating hTERT DNA as related to virus infection in liver carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(1A):223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang YJ, et al. Quantification of plasma hTERT DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients by quantitative fluorescent polymerase chain reaction. Clin Invest Med. 2011;34(4):E238. doi: 10.25011/cim.v34i4.15366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazurek AM, et al. Assessment of the total cfDNA and HPV16/18 detection in plasma samples of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oral Oncol. 2016;54:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metz CH, et al. Ultradeep sequencing detects GNAQ and GNA11 mutations in cell-free DNA from plasma of patients with uveal melanoma. Cancer Med. 2013;2(2):208–215. doi: 10.1002/cam4.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benesova L, et al. Mutation-based detection and monitoring of cell-free tumor DNA in peripheral blood of cancer patients. Anal Biochem. 2013;433(2):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crowley E, et al. Liquid biopsy: monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(8):472–484. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salvi S, et al. Cell-free DNA as a diagnostic marker for cancer: current insights. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6549–6559. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S100901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cree IA, et al. Guidance for laboratories performing molecular pathology for cancer patients. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(11):923–931. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bossuyt PM, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin Chem. 2015;61(12):1446–1452. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.246280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ladabaum U, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with blood-based biomarkers: cost-effectiveness of methylated septin 9 DNA versus current strategies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(9):1567–1576. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heitzer E, Ulz P, Geigl JB. Circulating tumor DNA as a liquid biopsy for cancer. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):112–123. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.222679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurihara S, et al. Circulating free DNA as non-invasive diagnostic biomarker for childhood solid tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(12):2094–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtz DM, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing. Blood. 2015;125(24):3679–3687. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-635169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman AM, et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med. 2014;20(5):548–554. doi: 10.1038/nm.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belic J, et al. Rapid identification of plasma DNA samples with increased ctDNA levels by a modified FAST-SeqS approach. Clin Chem. 2015;61(6):838–849. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.234286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersen RF, et al. Improved sensitivity of circulating tumor DNA measurement using short PCR amplicons. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;439:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellinger J, et al. CpG island hypermethylation of cell-free circulating serum DNA in patients with testicular cancer. J Urol. 2009;182(1):324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez-Galan J, et al. Quantitative detection of methylated ESR1 and 14-3-3-sigma gene promoters in serum as candidate biomarkers for diagnosis of breast cancer and evaluation of treatment efficacy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(6):958–965. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.6.5966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kristensen LS, et al. Methylation profiling of normal individuals reveals mosaic promoter methylation of cancer-associated genes. Oncotarget. 2012;3(4):450–461. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Page K, et al. Influence of plasma processing on recovery and analysis of circulating nucleic acids. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sorber L, et al. A comparison of cell-free DNA isolation kits: isolation and quantification of cell-free DNA in plasma. J Mol Diagn. 2017;19(1):162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Mattos-Arruda L, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8839. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taback B, Saha S, Hoon DS. Comparative analysis of mesenteric and peripheral blood circulating tumor DNA in colorectal cancer patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1075:197–203. doi: 10.1196/annals.1368.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uchida J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive genotyping of EGFR in lung cancer patients by deep sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA. Clin Chem. 2015;61(9):1191–1196. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.241414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandez-Cuesta L, et al. Identification of circulating tumor DNA for the early detection of small-cell lung cancer. EBioMedicine. 2016;10:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Warton K, Samimi G. Methylation of cell-free circulating DNA in the diagnosis of cancer. Front Mol Biosci. 2015;2:13. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2015.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Payne SR. From discovery to the clinic: the novel DNA methylation biomarker (m)SEPT9 for the detection of colorectal cancer in blood. Epigenomics. 2010;2(4):575–585. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Church TR, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut. 2014;63(2):317–325. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Potter NT, et al. Validation of a real-time PCR-based qualitative assay for the detection of methylated SEPT9 DNA in human plasma. Clin Chem. 2014;60(9):1183–1191. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.221044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toth K, et al. Circadian rhythm of methylated Septin 9, cell-free DNA amount and tumor markers in colorectal cancer patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Zhao QT, et al. Diagnostic value of SHOX2 DNA methylation in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3433–3439. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S94300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Begum S, et al. An epigenetic marker panel for detection of lung cancer using cell-free serum DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(13):4494–4503. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yi JM, et al. Novel methylation biomarker panel for the early detection of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(23):6544–6555. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diehl F, et al. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(45):16368–16373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507904102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin JK, et al. Clinical relevance of alterations in quantity and quality of plasma DNA in colorectal cancer patients: based on the mutation spectra detected in primary tumors. Ann Surg Oncol, 2014 21 Suppl. 4:S680–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Wang JY, et al. Molecular detection of APC, K- ras, and p53 mutations in the serum of colorectal cancer patients as circulating biomarkers. World J Surg. 2004;28(7):721–726. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Q, et al. A multiplex methylation-specific PCR assay for the detection of early-stage ovarian cancer using cell-free serum DNA. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(1):132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hauser S, et al. Serum DNA hypermethylation in patients with kidney cancer: results of a prospective study. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(10):4651–4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radpour R, et al. Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes involved in critical regulatory pathways for developing a blood-based test in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, et al. Methylation of multiple genes as a candidate biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2011;303(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Skrypkina I, et al. Concentration and methylation of cell-free DNA from blood plasma as diagnostic markers of renal cancer. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:3693096. doi: 10.1155/2016/3693096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pack SC, et al. Usefulness of plasma epigenetic changes of five major genes involved in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Int J Color Dis. 2013;28(1):139–147. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sikora K, et al. Evaluation of cell-free DNA as a biomarker for pancreatic malignancies. Int J Biol Markers. 2015;30(1):e136–e141. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsu HS, et al. Characterization of a multiple epigenetic marker panel for lung cancer detection and risk assessment in plasma. Cancer. 2007;110(9):2019–2026. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Couraud S, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of actionable mutations by deep sequencing of circulating free DNA in lung cancer from never-smokers: a proof-of-concept study from BioCAST/IFCT-1002. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(17):4613–4624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hyman DM, et al. Prospective blinded study of BRAFV600E mutation detection in cell-free DNA of patients with systemic histiocytic disorders. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(1):64–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thierry AR, et al. Clinical validation of the detection of KRAS and BRAF mutations from circulating tumor DNA. Nat Med. 2014;20(4):430–435. doi: 10.1038/nm.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim BH, et al. Detection of plasma BRAF(V600E) mutation is associated with lung metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56(3):634–640. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.3.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sharma G, et al. Clinical significance of promoter hypermethylation of DNA repair genes in tumor and serum DNA in invasive ductal breast carcinoma patients. Life Sci. 2010;87(3–4):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ibanez de Caceres I, et al. Tumor cell-specific BRCA1 and RASSF1A hypermethylation in serum, plasma, and peritoneal fluid from ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2004;64(18):6476–6481. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Melnikov A, et al. Differential methylation profile of ovarian cancer in tissues and plasma. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11(1):60–65. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liggett, T.E., et al., Distinctive DNA methylation patterns of cell-free plasma DNA in women with malignant ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol, 2011. 120(1): p. 113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Hulbert A, et al. Early detection of lung cancer using DNA promoter Hypermethylation in plasma and sputum. Clin Cancer Res. 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Chimonidou M, et al. CST6 promoter methylation in circulating cell-free DNA of breast cancer patients. Clin Biochem. 2013;46(3):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen L, et al. Hypermethylated FAM5C and MYLK in serum as diagnosis and pre-warning markers for gastric cancer. Dis Markers. 2012;32(3):195–202. doi: 10.1155/2012/473251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Melson J, et al. Commonality and differences of methylation signatures in the plasma of patients with pancreatic cancer and colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(11):2656–2662. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tian F, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in serum as potential biomarker for the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Powrozek T, et al. Methylation of the DCLK1 promoter region in circulating free DNA and its prognostic value in lung cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Powrozek T, et al. Methylation of the DCLK1 promoter region in circulating free DNA and its prognostic value in lung cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(4):398–404. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1382-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kloten V, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of the tumor-suppressor genes ITIH5, DKK3, and RASSF1A as novel biomarkers for blood-based breast cancer screening. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(1):R4. doi: 10.1186/bcr3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chiappetta C, et al. Use of a new generation of capillary electrophoresis to quantify circulating free DNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;425:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Szpechcinski A, et al. Plasma cell-free DNA levels and integrity in patients with chest radiological findings: NSCLC versus benign lung nodules. Cancer Lett. 2016;374(2):202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shao X, et al. Quantitative analysis of cell-free DNA in ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(6):3478–3482. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Andolfo I, et al. Detection of erbB2 copy number variations in plasma of patients with esophageal carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Papadopoulou E, et al. Cell-free DNA and RNA in plasma as a new molecular marker for prostate and breast cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1075:235–243. doi: 10.1196/annals.1368.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dumache R, et al. Prostate cancer molecular detection in plasma samples by glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) methylation analysis. Clin Lab. 2014;60(5):847–852. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2013.130701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Minciu R, et al. Molecular diagnostic of prostate cancer from body fluids using methylation-specific PCR (MS-PCR) method. Clin Lab. 2016;62(6):1183–6. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2015.151019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cassinotti E, et al. DNA methylation patterns in blood of patients with colorectal cancer and adenomatous colorectal polyps. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(5):1153–1157. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shan M, et al. Detection of aberrant methylation of a six-gene panel in serum DNA for diagnosis of breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(14):18485–18494. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Huang G, et al. Evaluation of INK4A promoter methylation using pyrosequencing and circulating cell-free DNA from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52(6):899–909. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kuo YB, et al. Comparison of KRAS mutation analysis of primary tumors and matched circulating cell-free DNA in plasmas of patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;433:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spindler KL, et al. Circulating free DNA as biomarker and source for mutation detection in metastatic colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0108247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Freidin MB, et al. Circulating tumor DNA outperforms circulating tumor cells for KRAS mutation detection in thoracic malignancies. Clin Chem. 2015;61(10):1299–1304. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.242453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sozzi G, et al. Detection of microsatellite alterations in plasma DNA of non-small cell lung cancer patients: a prospect for early diagnosis. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(10):2689–2692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Eisenberger CF, et al. The detection of oesophageal adenocarcinoma by serum microsatellite analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32(9):954–960. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Castagnaro A, et al. Microsatellite analysis of induced sputum DNA in patients with lung cancer in heavy smokers and in healthy subjects. Exp Lung Res. 2007;33(6):289–301. doi: 10.1080/01902140701539687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Andriani F, et al. Detecting lung cancer in plasma with the use of multiple genetic markers. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(1):91–96. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Xia P, et al. Decreased mitochondrial DNA content in blood samples of patients with stage I breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:454. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kadam SK, Farmen M, Brandt JT. Quantitative measurement of cell-free plasma DNA and applications for detecting tumor genetic variation and promoter methylation in a clinical setting. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14(4):346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zaher ER, et al. Cell-free DNA concentration and integrity as a screening tool for cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2013;50(3):175–183. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.118721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Danese E, et al. Epigenetic alteration: new insights moving from tissue to plasma - the example of PCDH10 promoter methylation in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(3):807–813. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Skvortsova TE, et al. Cell-free and cell-bound circulating DNA in breast tumours: DNA quantification and analysis of tumour-related gene methylation. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(10):1492–1495. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hoque MO, et al. Detection of aberrant methylation of four genes in plasma DNA for the detection of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(26):4262–4269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Salvianti F, et al. Tumor-related methylated cell-free DNA and circulating tumor cells in melanoma. Front Mol Biosci. 2015;2:76. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2015.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rykova EY, et al. Investigation of tumor-derived extracellular DNA in blood of cancer patients by methylation-specific PCR. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2004;23(6–7):855–859. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200026031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mohamed NA, et al. Is serum level of methylated RASSF1A valuable in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic viral hepatitis C? Arab J Gastroenterol. 2012;13(3):111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhang YJ, et al. Predicting hepatocellular carcinoma by detection of aberrant promoter methylation in serum DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(8):2378–2384. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.de Martino M, et al. Serum cell-free DNA in renal cell carcinoma: a diagnostic and prognostic marker. Cancer. 2012;118(1):82–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.deVos T, et al. Circulating methylated SEPT9 DNA in plasma is a biomarker for colorectal cancer. Clin Chem. 2009;55(7):1337–1346. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.115808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Grutzmann R, et al. Sensitive detection of colorectal cancer in peripheral blood by septin 9 DNA methylation assay. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Toth K, et al. Detection of methylated septin 9 in tissue and plasma of colorectal patients with neoplasia and the relationship to the amount of circulating cell-free DNA. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Powrozek T, et al. Septin 9 promoter region methylation in free circulating DNA-potential role in noninvasive diagnosis of lung cancer: preliminary report. Med Oncol. 2014;31(4):917. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0917-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jin P, et al. Performance of a second-generation methylated SEPT9 test in detecting colorectal neoplasm. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(5):830–833. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Warren JD, et al. Septin 9 methylated DNA is a sensitive and specific blood test for colorectal cancer. BMC Med. 2011;9:133. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kneip C, et al. SHOX2 DNA methylation is a biomarker for the diagnosis of lung cancer in plasma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(10):1632–1638. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318220ef9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Weiss G, et al. Validation of the SHOX2/PTGER4 DNA methylation marker panel for plasma-based discrimination between patients with malignant and nonmalignant lung disease. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chimonidou M, et al. SOX17 promoter methylation in circulating tumor cells and matched cell-free DNA isolated from plasma of patients with breast cancer. Clin Chem. 2013;59(1):270–279. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.191551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lange CP, et al. Genome-scale discovery of DNA-methylation biomarkers for blood-based detection of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The papers quoted are publically available from the publishers, and many are now open access.