Abstract

Background

From earlier studies it is known that the APOE ε2/ε3/ε4 polymorphism modulates the concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) beta-amyloid1–42 (Aβ42) in patients with cognitive decline due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as well as in cognitively healthy controls. Here, in a large cohort consisting solely of cognitively healthy individuals, we aimed to evaluate how the effect of APOE on CSF Aβ42 varies by age, to understand the association between APOE and the onset of preclinical AD.

Methods

APOE genotype and CSF Aβ42 concentration were determined in a cohort comprising 716 cognitively healthy individuals aged 17–99 from nine different clinical research centers.

Results

CSF concentrations of Aβ42 were lower in APOE ε4 carriers than in noncarriers in a gene dose-dependent manner. The effect of APOE ε4 on CSF Aβ42 was age dependent. The age at which CSF Aβ42 concentrations started to decrease was estimated at 50 years in APOE ε4-negative individuals and 43 years in heterozygous APOE ε4 carriers. Homozygous APOE ε4 carriers showed a steady decline in CSF Aβ42 concentrations with increasing age throughout the examined age span.

Conclusions

People possessing the APOE ε4 allele start to show a decrease in CSF Aβ42 concentration almost a decade before APOE ε4 noncarriers already in early middle age. Homozygous APOE ε4 carriers might deposit Aβ42 throughout the examined age span. These results suggest that there is an APOE ε4-dependent period of early alterations in amyloid homeostasis, when amyloid slowly accumulates, that several years later, together with other downstream pathological events such as tau pathology, translates into cognitive decline.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, APOE, Cerebrospinal fluid, Beta amyloid

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the accumulation of extracellular beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and intracellular tau tangles [1]. AD pathology is multifactorial with both genetic and environmental risk factors, with the most prominent susceptibility gene being apolipoprotein E (APOE) [2]. The APOE gene is polymorphic, with three different alleles, of which the ε4 allele is associated with an increased risk, as well as a lower age at onset, of AD. Heterozygous APOE ε4 carriers have an approximately 3-fold increase of risk compared with individuals lacking the ε4 allele, whereas the increase of risk is up to 12-fold in homozygous APOE ε4 carriers [3]. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms for this strong genetic association are still unknown, but may involve direct or indirect effects on Aβ aggregation or clearance [4, 5].

Measurement of the 42 amino acid isoform of Aβ (Aβ42) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is used alongside CSF total tau (T-tau) and CSF phosphorylated tau (P-tau) as a diagnostic tool for AD [6]. Decreased concentrations of CSF Aβ42 are indicative of cerebral amyloid pathology during the entire course of the disease, from preclinical asymptomatic disease to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia, and may even indicate disturbed amyloid metabolism before amyloid deposition may be visualized by amyloid PET imaging [7–9]. An association between the APOE genotype and CSF concentrations of Aβ42 has been described previously among patients with AD and MCI, as well as in healthy controls, with the APOE ε4 allele being associated with lower CSF Aβ42 concentrations in a gene dose-dependent manner [10–15]. However, because most studies have only analyzed older people, it is not clear whether this effect is present in all age groups irrespective of preexisting amyloid pathology, especially since an earlier study showed the effect to be absent in a small cohort of younger cognitively healthy individuals [14].

Consequently, the question that arises is at what age the potential effects of APOE ε4 on CSF Aβ42 can be detected. To tackle this question, we analyzed CSF Aβ42 as well as the APOE ε4 genotype in a large cohort consisting of 716 cognitively healthy individuals from 17 to 99 years of age. Specifically, we tested how CSF Aβ42 concentrations differ by age in the different APOE ε4 carrier groups.

Methods

Cohorts

The total cohort consisted of 716 cognitively healthy individuals from nine different centers in Sweden, Finland, Germany, and Italy with age ranging from 17 to 99 years. All centers were specialized memory clinics, except one, which is a psychiatry clinic specialized in affective disorders. All subjects underwent neurological examination as well as cognitive testing to exclude cognitive impairment. One of the subcohorts contained 138 patients with bipolar disorder, whereas the rest of the participants (n = 578) were healthy volunteers. Most study participants (except the bipolar disorder patients, who were recruited among patients at the specialized affective disorders clinic) were recruited by advertisement or among relatives or friends of patients who were evaluated on suspicion of cognitive dysfunction.

Lumbar puncture

CSF samples were obtained by lumbar puncture in the L3/4 or L4/5 interspace, collected in polypropylene tubes, centrifuged, and stored frozen at –80 °C until analysis according to standard operating procedures [6]. The time frame during which samples were collected in each center in relation to the time of sample analysis was less than 5 years in all cohorts. Long-term stability of CSF Aβ42 at –80 °C has been evaluated in several studies [16–18], all of which show that CSF Aβ42 is stable at –80 °C. The majority of the biomarker analyses were performed at the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, but samples from Kuopio, Finland and Munich, Germany as well as from Italy were analyzed in local laboratories.

CSF analyses

CSF Aβ42 concentrations were measured using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42]; Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium) designed to detect the 1st and 42nd amino acids in the Aβ protein as described previously [19]. A subset of the samples was analyzed using a multiplex semiautomated assay platform (xMAP Luminex AlzBio3; Fujirebio) as described previously [20]. All analyses were performed by experienced laboratory technicians who were blinded to all clinical information.

To adjust for variation in biomarker concentrations between the different laboratories, data were normalized by defining the largest center cohort as the reference group and then calculating factors between the APOE ε4-negative individuals from each participating center and the APOE ε4-negative individuals in the reference group. These factors were then applied to all data, hence relating biomarker concentrations in all of the different center cohorts to those in the reference group. There were no significant correlations between age and CSF Aβ42 concentrations in all but one of the subcohorts (in which the effect was minor, r 2 = –0.036, P = 0.037), which points toward a lack of a primary relation between these two parameters. Note that since the center cohort that was defined as the reference group used the xMAP Luminex AlzBio3 assay, the normalized concentrations of Aβ42 in this material were lower than the corresponding concentrations when using the INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] assay.

APOE alleles

Genotyping for APOE (gene map locus 19q13.2) was performed using allelic discrimination technology (TaqMan; Applied Biosystems) or equivalent techniques. Genotypes were obtained for the two single nucleotide polymorphisms that define the ε2, ε3, and ε4 alleles.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of biomarker concentrations between APOE ε4 carrier groups were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for several independent samples. Comparisons of genotype frequencies between patients with bipolar disorder and healthy volunteers were performed using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05 and all statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The trajectory of CSF Aβ42 concentrations with respect to age in different APOE ε4 carrier groups was modeled using restricted cubic splines and ordinary least squares regression. The Akaike Information Criterion selected the optimal model to be estimated using three spline knots. Regression models included gender and the interaction between the two-parameter spline representation of age and APOE ε4 group and the main effects for age and APOE ε4 group. Age at the initial decline of CSF Aβ42 concentrations was taken to be the maximum Aβ42 concentration prior to a monotone descent with increasing age. Confidence intervals for age at initial decline were estimated using the margins (2.5 and 97.5 percentiles) of 500 bootstrap samples.

Results

Demographic, genetic, and biochemical data

The majority of individuals in the total cohort (70.7%) lacked the APOE ε4 allele, with 26.5% being heterozygous and 2.8% being homozygous APOE ε4 carriers (Table 1). The subcohort consisting of patients with bipolar disorder had similar APOE ε4 genotype frequency (P = 0.633) as well as similar concentrations of CSF Aβ42 (P = 0.302) compared to the healthy volunteers and was therefore pooled with the rest of the total cohort (data not shown). There were neither any gender differences with regards to APOE ε4 genotype frequency (P = 0.586) or CSF Aβ42 concentrations (P = 0.534). Table 2 presents detailed demographic and biochemical data for all of the subcohorts included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic, genetic, and biochemical data in the total cohort as well as divided into three age tertiles

| Total cohort (n = 716) | ≤45 years (n = 237) | 46–64 years (n = 242) | ≥65 years (n = 237) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (years), mean (range) | 53.3 (17–99) | 29.9 (17–45) | 57.3 (46–64) | 72.6 (65–99) |

| Male, n (%) | 305 (42.6) | 114 (48.1) | 104 (43.0) | 87 (36.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 411 (57.4) | 123 (51.9) | 138 (57.0) | 150 (63.3) |

| Genetic | ||||

| APOE ε4–/–, n (%) | 506 (70.7) | 162 (68.4) | 172 (71.1) | 172 (72.6) |

| APOE ε4+/–, n (%) | 190 (26.5) | 69 (29.1) | 64 (26.4) | 57 (24.1) |

| APOE ε4+/+, n (%) | 20 (2.8) | 6 (2.5) | 6 (2.5) | 8 (3.4) |

| Biochemical: CSF Aβ42 (ng/L), mean (SD) | ||||

| All genotypes | 252.1 (71.0) | 251.9 (67.8) | 264.9 (67.7) | 239.2 (75.2) |

| APOE ε4–/– | 261.2 (70.9) | 257.2 (69.5) | 274.5 (68.1) | 251.8 (73.4) |

| APOE ε4+/– | 234.8 (65.4) | 241.4 (64.0) | 248.1 (58.3) | 211.9 (69.7) |

| APOE ε4+/+ | 185.5 (59.0) | 231.3 (51.8) | 167.8 (39.1) | 164.4 (62.1) |

| P value* | <0.001 | 0.203 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

*P values indicate comparisons of CSF Aβ42 concentrations between the APOE ε4 carrier groups (for the total cohort as well as for each of the tertiles)

APOE apolipoprotein E, Aβ42 beta-amyloid1– 42, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, SD standard deviation

Table 2.

Demographic, genetic, and biochemical data in the individual subcohorts

| Total cohort (n = 716) | Cohort 1a (n = 138) | Cohort 1b (n = 72) | Cohort 2 (n = 81) | Cohort 3 (n = 121) | Cohort 4 (n = 39) | Cohort 5 (n = 37) | Cohort 6 (n = 48) | Cohort 7 (n = 58) | Cohort 8 (n = 24) | Cohort 9 (n = 44) | Cohort 10 (n = 54) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Gothenburg, Sweden | Gothenburg, Sweden | Perugia, Italy | Stockholm, Sweden | Malmö, Sweden | Malmö, Sweden | Mölndal, Sweden | Kuopio, Finland | Munich, Germany | Stockholm, Sweden | Mölndal, Sweden | |

| Type of clinic | Affective disorders clinic | Affective disorders clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | Memory clinic | |

| Diagnosis | Bipolar disorder | Controls | Controls | Controls | Controls | Controls | Controls | Controls | Controls | Controls | Controls | |

| Age (years), mean (range) | 53.3 (17–99) | 39.4 (20–73) | 37.9 (21–74) | 53.0 (21–88) | 68.0 (40–92) | 72.4 (60–87) | 62.9 (42–99) | 66.6 (52–80) | 65.6 (45–81) | 63.0 (49–84) | 60.9 (23–88) | 22.0 (17–34) |

| Male, n (%) | 305 (42.6) | 55 (39.9) | 27 (37.5) | 22 (27.2) | 36 (29.8) | 15 (38.5) | 16 (43.2) | 22 (45.8) | 30 (51.7) | 15 (62.5) | 19 (43.2) | 48 (88.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 411 (57.4) | 83 (60.1) | 45 (62.5) | 59 (72.8) | 85 (70.2) | 24 (61.5) | 21 (56.8) | 26 (54.2) | 28 (48.3) | 9 (37.5) | 25 (56.8) | 6 (11.1) |

| APOE ε4–/–, n (%) | 506 (70.7) | 93 (67.4) | 49 (68.1) | 65 (80.2) | 88 (72.7) | 29 (74.4) | 25 (67.6) | 32 (66.7) | 40 (69.0) | 19 (79.2) | 31 (70.5) | 35 (64.8) |

| APOE ε4+/–, n (%) | 190 (26.5) | 41 (29.7) | 20 (27.8) | 14 (17.3) | 32 (26.4) | 10 (25.6) | 10 (27.0) | 15 (31.3) | 16 (27.6) | 5 (20.8) | 11 (25.0) | 16 (29.6) |

| APOE ε4+/+, n (%) | 20 (2.8) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (4.2) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (5.6) |

| CSF Aβ42 assay and concentrations measured (ng/L), mean (SD) | xMAP Luminex AlzBio3 | xMAP Luminex AlzBio3 | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | xMAP Luminex AlzBio3 | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | INNOTEST β-amyloid[1–42] | |

| All genotypes | 252.1 (71.0) | 257.7 (57.7) | 255.1 (54.2) | 260.2 (91.5) | 250.8 (75.8) | 260.3 (67.6) | 245.4 (58.7) | 250.3 (39.8) | 242.2 (71.9) | 247.6 (72.3) | 259.0 (92.4) | 232.1 (84.6) |

| APOE ε4–/– | 261.2 (70.9) | 264.6 (57.2) | 259.8 (51.7) | 262.5 (93.9) | 264.0 (68.2) | 260.8 (66.0) | 257.5 (66.2) | 258.3 (36.8) | 258.5 (75.0) | 260.9 (72.9) | 276.6 (89.1) | 240.6 (93.0) |

| APOE ε4+/– | 234.8 (65.4) | 250.5 (51.4) | 245.3 (63.1) | 266.4 (76.0) | 219.7 (82.5) | 258.9 (75.7) | 220.3 (29.0) | 241.7 (31.4) | 205.4 (52.2) | 197.0 (46.3) | 230.0 (90.4) | 216.0 (66.6) |

| APOE ε4+/+ | 185.5 (59.0) | 172.0 (67.9) | 243.3 (21.1) | 139.3 (24.6) | 87.5 (N/A) | N/A | 219.2 (13.4) | 125.7 (N/A) | 209.7 (10.0) | N/A | 143.9 (31.5) | 218.0 (75.1) |

APOE apolipoprotein E, Aβ42 beta-amyloid1–42, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, SD standard deviation, N/A not available

CSF Aβ42 concentrations in relation to APOE genotype

In the total cohort, CSF Aβ42 concentrations were lower in APOE ε4 carriers than in noncarriers in a gene dose-dependent manner (P < 0.001, Table 1), which is in keeping with earlier findings [14]. However, when dividing the total cohort into tertiles according to age, the effect was present in the middle and upper tertiles among individuals aged 46 or older (P < 0.001, Table 1), whereas in the lower tertile, containing individuals aged 45 or younger, the difference was nonsignificant (P = 0.203, Table 1).

CSF Aβ42 concentrations across different age groups

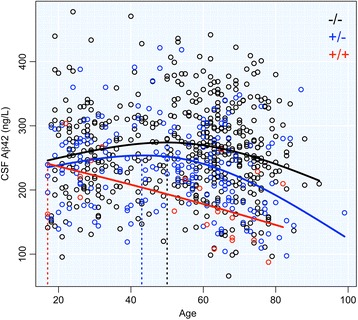

The estimated curves showed an initial upslope of CSF Aβ42 concentrations in APOE ε4-negative individuals and heterozygous APOE ε4 carriers followed by a steep descent (Fig. 1). Aβ42 concentrations in homozygous APOE ε4 carriers, however, descended from an early age lacking the initial upslope. The age of initial descent, defined as the age at which CSF Aβ42 reaches its maximum, was estimated at 50 (95% confidence interval (CI) 42–54) years for APOE ε4-negative individuals and 43 (95% CI 17–48) years for heterozygous APOE ε4 carriers. This number could not be estimated in homozygous APOE ε4 carriers, as they lacked the initial upslope.

Fig. 1.

CSF Aβ42 concentrations plotted against age. Mean curves for the three APOE ε4 groups: black, APOE ε4–/–; blue, APOE ε4+/–; red, APOE ε4+/+. Vertical lines indicate age at initial decline of CSF Aβ42. Aβ42 beta-amyloid1–42, CSF cerebrospinal fluid

Discussion

We conducted a large multicenter study to assess how effects of the APOE ε2/ε3/ε4 polymorphism on CSF Aβ42 concentrations vary by age in cognitively healthy individuals. The main findings were that: the APOE ε4 allele was associated with lower CSF Aβ42 concentrations overall in cognitively healthy people; the effects of APOE ε4 were present in older people but not in young people; and CSF Aβ42 started to decline at age 50 in people without the APOE ε4 allele, at age 43 in people carrying one APOE ε4 allele, and even earlier in people carrying two APOE ε4 alleles. Taken together, these findings show that APOE ε4 strongly modulates the effect of age on CSF Aβ42 in cognitively healthy people, and points to important age-dependent effects of APOE ε4 on the development of preclinical AD.

Comparisons of CSF Aβ42 and amyloid PET imaging in cognitively healthy people suggest that the first decline in CSF Aβ42 does not always translate to widespread cerebral amyloid deposition [7, 8, 21]. The age at which CSF Aβ42 concentrations start to decrease may therefore be the starting point for preclinical pathological disturbances in amyloid homeostasis, which ultimately results in amyloid accumulation that later becomes detectable on amyloid PET imaging. The data from this study suggest that the disturbed amyloid homeostasis occurs on average from age 50 in APOE ε4-negative individuals, and almost a decade earlier in APOE ε4 heterozygous people. In APOE ε4 homozygous people we estimated a descent in CSF Aβ42 already from age 17, but the sparsity of data among young homozygous APOE ε4 carriers makes this estimate uncertain, and we can only conclude that the decline in CSF Aβ42 starts considerably earlier in homozygous APOE ε4 carriers compared with heterozygous APOE ε4 carriers or noncarriers. Importantly, previous studies provide convergent evidence that emerging amyloid pathology, defined as decreased CSF Aβ42 concentrations, or CSF Aβ42 concentrations slightly above conventional thresholds for amyloid positivity, may have deleterious effects on brain structure, brain function, and cognition [22–25]. This highlights the importance of detecting the earliest effects of APOE ε4 on CSF Aβ42 in order to provide very early diagnostics and potentially initiate prevention of AD.

The fact that APOE ε4 affected CSF Aβ42 concentrations already from 43 years of age is interesting since a previous study found that APOE ε4 was associated with cognitive decline only after 50 years of age [26]. We therefore suggest that there is an intermediate period of early alterations in amyloid homeostasis before cognitive decline becomes detectable [23], when amyloid accumulation slowly builds up together with downstream pathological events (including spread of tau tangles), which ultimately translate to cognitive decline several years later.

This study has several limitations. First, we used cross-sectional data from several cohorts and several assays to measure CSF Aβ42. Although we employed normalization measures to bridge all results, the variability in cohorts and assays increases the variance of our models and estimates. Future studies are needed to verify these results in a monocenter setting, obviating the need for data normalization across cohorts. Second, the low number of APOE ε4 homozygous people, along with the sparsity of data in the age span between 85 and 100 years, limits our ability to model effects of APOE ε4 homozygosity and effects in the final part of the natural life span. Also, the lack of APOE ε4 homozygous people between age 35 and 50 makes it impossible to define whether there is a plateau in Aβ42 concentrations before decline or whether the concentrations drop directly from age 17 in homozygous APOE ε4 carriers.

Conclusions

To sum up, the results of this study suggest that the process of preclinical Aβ pathology might start in early middle age in APOE ε4 carriers. Hence, we hypothesize that the APOE ε4 allele affects CSF Aβ42 concentrations by speeding up the process of preclinical Aβ accumulation and deposition in the brain. Studies addressing the molecular mechanisms behind the association between ApoE and cerebral Aβ build-up are needed to verify this.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the European Research Council, Frimurarestiftelsen, Stiftelsen Gamla Tjänarinnor, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation, the Swedish Brain Foundation, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, and the Torsten Söderberg Foundation. HH is supported by the AXA Research Fund, the Fondation Université Pierre et Marie Curie, and the Fondation pour la Recherche sur Alzheimer, Paris, France. The research leading to these results has received funding from the program “Investissements d’avenir” ANR-10-IAIHU-06 (to HH).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- APOE

Apolipoprotein E

- Aβ42

Beta-amyloid1–42

- CI

Confidence interval

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- P-tau

Phosphorylated tau

- T-tau

Total tau

Authors’ contributions

RL, KB, NM, and HZ created the concept and design for the study. RL, BO, ML, GBF, S-KH, HH, AW, OH, KB, NM, and HZ acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data. RL, PSI, NM, and HZ drafted the manuscript. RL, PSI, and NM performed the statistical analyses. The study was supervised by NM and HZ. All authors contributed critical revision for important intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received approval from regional ethical committees at the Universities of Gothenburg and Lund (Sweden), Brescia (Italy), Kuopio (Finland), and Munich (Germany) and followed the tenets of the Helsinki declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ML declares that, over the past 36 months, he has received lecture honoraria from Lundbeck and AstraZeneca Sweden, and served as scientific consultant for EPID Research Oy; he has no other equity ownership, profit-sharing agreements, royalties, or patents. HH declares no competing financial interests related to the present article; he serves as Senior Associate Editor for the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia; he has been a scientific consultant and/or speaker and/or attended scientific advisory boards of Axovant, Anavex, Eli Lilly and company, GE Healthcare, Cytox, Qynapse, Roche, Biogen Idec, Takeda-Zinfandel, Oryzon Genomics; he receives research support from the Fondation for Alzheimer Research (Paris), COLAM Initiatives (Paris), IHU-A-ICM (Paris), Pierre and Marie Curie University (Paris), Pfizer & Avid (paid to institution); and he has patents as inventor, but received no royalties. OH has acquired research support (for the institution) from Roche, GE Healthcare, Biogen, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Fujirebio, and Euroimmun; in the past 2 years, he has received consultancy/speaker fees (paid to the institution) from Lilly, Roche, and Fujirebio. KB has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Alzheon, BioArctic, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Fujirebio Europe, IBL International, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics. HZ has served on the scientific advisory board for Roche Diagnostics, Eli Lilly and Pharmasum Therapeutics. KB and HZ are cofounders of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures-based platform company at the University of Gothenburg. RL, PSI, TS, BO, GBF, S-KH, AW, LM, and NM declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–3. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006312. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellano JM, Kim J, Stewart FR, Jiang H, DeMattos RB, Patterson BW, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Mawuenyega KG, Cruchaga C, et al. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-β peptide clearance. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:89ra57. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verghese PB, Castellano JM, Garai K, Wang Y, Jiang H, Shah A, Bu G, Frieden C, Holtzman DM. ApoE influences amyloid-β (Aβ) clearance despite minimal apoE/Aβ association in physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E1807–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220484110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blennow K, Hampel H, Weiner M, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:131–44. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, Landau S, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Weiner MW. Independent information from cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β and florbetapir imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2015;138:772–83. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, Hansson O. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis detects cerebral amyloid-β accumulation earlier than positron emission tomography. Brain. 2016;139:1226–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blennow K, Mattsson N, Scholl M, Hansson O, Zetterberg H. Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galasko D, Chang L, Motter R, Clark CM, Kaye J, Knopman D, Thomas R, Kholodenko D, Schenk D, Lieberburg I, et al. High cerebrospinal fluid tau and low amyloid β42 levels in the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and relation to apolipoprotein E genotype. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:937–45. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunderland T, Mirza N, Putnam KT, Linker G, Bhupali D, Durham R, Soares H, Kimmel L, Friedman D, Bergeson J, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid1-42 and tau in control subjects at risk for Alzheimer's disease: the effect of APOE ε4 allele. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:670–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:403–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Aisen PS, Weiner M, Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr Effect of apolipoprotein E on biomarkers of amyloid load and neuronal pathology in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:308–16. doi: 10.1002/ana.21953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lautner R, Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Wallin A, Palsson E, Jakobsson J, Herukka SK, Owenius R, Olsson B, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and the diagnostic accuracy of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Psychiat. 2014;71:1183–91. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prince JA, Zetterberg H, Andreasen N, Marcusson J, Blennow K. APOE ε4 allele is associated with reduced cerebrospinal fluid levels of Aβ42. Neurology. 2004;62:2116–8. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000128088.08695.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schipke CG, Jessen F, Teipel S, Luckhaus C, Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, Frolich L, Maier W, Ruther E, Heppner FL, et al. Long-term stability of Alzheimer's disease biomarker proteins in cerebrospinal fluid. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26:255–62. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhlmann J, Andreasson U, Pannee J, Bjerke M, Portelius E, Leinenbach A, Bittner T, Korecka M, Jenkins RG, Vanderstichele H, et al. CSF Aβ1-42—an excellent but complicated Alzheimer's biomarker—a route to standardisation. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;467:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjerke M, Portelius E, Minthon L, Wallin A, Anckarsater H, Anckarsater R, Andreasen N, Zetterberg H, Andreasson U, Blennow K. Confounding factors influencing amyloid beta concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;2010:986310. doi: 10.4061/2010/986310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreasen N, Hesse C, Davidsson P, Minthon L, Wallin A, Winblad B, Vanderstichele H, Vanmechelen E, Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid(1-42) in Alzheimer disease: differences between early- and late-onset Alzheimer disease and stability during the course of disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:673–80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsson A, Vanderstichele H, Andreasen N, De Meyer G, Wallin A, Holmberg B, Rosengren L, Vanmechelen E, Blennow K. Simultaneous measurement of β-amyloid(1-42), total tau, and phosphorylated tau (Thr181) in cerebrospinal fluid by the xMAP technology. Clin Chem. 2005;51:336–45. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.039347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:122–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Insel PS, Mattsson N, Donohue MC, Mackin RS, Aisen PS, Jack CR, Jr, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW. The transitional association between β-amyloid pathology and regional brain atrophy. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1171–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insel PS, Mattsson N, Mackin RS, Scholl M, Nosheny RL, Tosun D, Donohue MC, Aisen PS, Jagust WJ, Weiner MW. Accelerating rates of cognitive decline and imaging markers associated with β-amyloid pathology. Neurology. 2016;86:1887–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattsson N, Insel PS, Nosheny R, Tosun D, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Jack CR, Jr, Donohue MC, Weiner MW. Emerging β-amyloid pathology and accelerated cortical atrophy. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:725–34. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, Jagust W, Sperling R, Aisen P, Weiner MW. Predicting reduction of cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 in cognitively healthy controls. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:554–60. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caselli RJ, Dueck AC, Osborne D, Sabbagh MN, Connor DJ, Ahern GL, Baxter LC, Rapcsak SZ, Shi J, Woodruff BK, et al. Longitudinal modeling of age-related memory decline and the APOE ε4 effect. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:255–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.