Introduction

The inflatable penile prosthesis (IPP) is the gold standard in surgical management for erectile dysfunction that is refractory to medical therapy. Patients and their partners report exceptionally high satisfaction rates.1 Since the development of the IPP in the 1970s, several innovations have been made to enhance the function, reliability, and cosmesis.2–4 Currently, Coloplast® (Minneapolis, MN) and Boston Scientific (Natick, MA; formerly American Medical Systems [AMS]®) are the two major manufacturers of inflatable penile prostheses in the United States.

Over the past several decades several important changes have been made to the IPP devices including the introduction of the lockout valve,5 antibiotic coatings,6, 7 and flat reservoirs.8 While the clinical trials have evaluated many of these improvements, there has been little biomechanical research to validate the mechanical attributes or the marketing claims of each company.

Mechanically, the implants differ in that the Coloplast Titan is marketed as expanding circumferentially, whereas the AMS 700 LGX is advertised as expanding both in length and girth.2, 9, 10 The most recent study evaluating biomechanical properties of the IPP was performed in 1993 by Goldstein and colleagues.11 This gap in research underscores the surprising lack of data available for an otherwise commonly used device.

While both the Coloplast and AMS devices have many similarities, there is little data to support which device is advantageous and in what scenario a surgeon should choose one manufacturer over the other. There is no evidence that the devices produced by the two manufacturers are so similar that this decision is merely ‘surgeon’s preference.’ In our men’s health clinic, we have anecdotally identified that some patients were dissatisfied with the rigidity of their device for penetration after being trained on proper use. We also noted that some men without any prior evidence of Peyronie’s disease had some penile curvature after prolonged use. Finally, we heard from many men that their phallus hangs in a more dependent position after placement of the IPP. These complaints led us to wonder if there were differences in the mechanical capabilities of the two devices causing these complaints and could we demonstrate the differences in the laboratory.

Given the anecdotal discrepancy in rigidity, penile dependence and curvature that we observed in the clinic, we performed a blinded biomechanical study to compare the two sizes of Coloplast Titan to the AMS 700 LGX. Our goal is to report objective end points to highlight the inherent differences between the two devices. The penile implant is designed to emulate an erection in the form of a hydraulic pump. We set out to test two functions of the implants during intercourse, which are penetration (longitudinal column rigidity) and horizontal lie of the penis (horizontal rigidity). With respect to mechanical device failure during longitudinal column rigidity, we denoted a visible cylinder kink. To evaluate turgidity we measured horizontal rigidity, which simulated resistance to bending with gravity.

Materials and Methods

We compared four inflatable penile prostheses models in a blinded fashion: the Coloplast Titan (18cm and 22cm) and the AMS 700 LGX (18cm and 21cm). Testing was performed at the Rice University Materials Science and NanoEngineering Department. The individuals performing the testing were blinded to manufacturer and had no prior experience testing in this device field. All tests were performed in the presence of the lead author who is an Andrology fellowship trained Urologist with experience placing both implants.

Each implant’s system was tested apart from its fluid reservoir for ease of testing. The cylinder/pump assembly was inflated with 0.9% normal saline to various fill pressures using a 60 cc syringe as surrogate reservoir. The cylinders were pressurized into an intact column by pumping. Each pump delivered approximately 7cc of saline solution per pump action (based on manufacturer specifications) until the test pressures selected were reached. Prior to pressurizing, a “tee” was placed in line between the pump and the implant cylinder. The pumping action produced pressure readings on the pressure gauge placed on the tee. When a desired pressure was reached, a hemostat was used to clamp off the cylinder so the tee could be removed. Because we noted differences in volumes required to completely fill each cylinder, we used devices pressures as a constant to compare device column failure. A hemostat was then used to clamp off the tube to maintain desired pressure after the pressure was achieved. We compared each device at an inflation pressure of 10, 15, and 20 pounds per square inch (68.9, 103.4, 137.9 kPa). The cylinder’s length and diameter were measured before being placed in the test fixtures once they were pressurized. Because patients may not fill the device to maximum inflation due to preference or physical inability, we tested each implant at various levels of inflation to simulate clinical usage. All testing was documented and preserved on video.

Longitudinal Column Load Testing (To Simulate Penetration)

To simulate penetration, we performed a longitudinal column load test. We designated compromised column strength as a visible kink seen in the cylinder. The cylinders were compressed along their longitudinal axes and were fastened into the machine with custom-machined metal holders. The testing machine compressed the implants longitudinally at an automated setting of 1 inch/minute (2.54cm/min). Each cylinder was tested individually by the ADMET eXpert 7600 Single Column Testing Machine. Sensors recorded the length of compression sustained until the implant kinked and recorded the load of pressure throughout compression to device. Compromise of rigidity was identified as a visual kink in the device cylinder created by the compression. This kink could also be observed on the load-curve generated by the ADMET eXpert 7600. Data was then recorded and plotted for both compression length and load sustained. Each implant was tested individually as it was not possible on our platform to test side by side. We tested both cylinders from each manufacturer to minimize intra-cylindrical variation within a device. We defined maximum load as the force required to generate a kink in the cylinder which was determined both visually and can be identified by a sudden drop in load pressure during testing.

Cantilever Testing (Horizontal Penile Lie)

To replicate resistance to bending with gravity or penile lie we examined horizontal rigidity. We looked at change in device angle in a loaded and unloaded setting in the form of a cantilever test. The cantilever test is modeled off ASTM D747 – 10. The inflated cylinders were hung horizontally and were fastened into custom-machined metal holder secured on a horizontal surface. Horizontal bend was measured with the device unloaded and with a weight of 20 grams applied 76mm from the base of the implant to simulate a bending load (loaded). The deflection angle and deflection were recorded. We tested each implant at various levels of inflation to simulate clinical usage of the prosthetic devices where patients may not fill the device to maximum inflation due to preference or physical inability. We compared each device at an inflation pressure of 10, 15, and 20 pounds per square inch of pressure. Although each implant was tested individually due to limitations of the testing platform, we tested both cylinders from each implant to minimize intra-cylindrical variation within a device. Both cylinders for each implant were tested.

Results

Two sizes of implantable cylinder pump assemblies from two manufacturers of penile prostheses were tested for their ability to withstand longitudinal column loads (penetration) at various pressures. The length and diameter of each device was measured prior to longitudinal column testing (penetration) at various fill pressures (0, 10, 15, 20 PSI) (Table 1). Measurement confirmed the stated sizes of the AMS (18, 21 cm) and Coloplast devices (18, 22 cm) at 0 PSI. Both AMS cylinders increased in length but not in diameter with increasing fill pressure. In contrast, the Coloplast implants saw a minimal increase in length with increasing fill pressures. Only the 18cm Coloplast Titan had an increase in diameter with filling. Fill volumes of each device were similar between the 18cm cylinders at each fill pressure (42–70cc). The AMS 21cm device and the Coloplast 22cm device had greater fill volumes (50–70cc and 76–111cm respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Length and diameter of devices at different fill pressures (0, 10, 15, 20 PSI).

| Device | Boston Scientific 700 LGX | Coloplast Titan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (cm) | 18(1) | 18(2) | 21(1) | 21(2) | 18(1) | 18(2) | 22(1) | 22(2) |

| Pressure PSI (kPa) | Length (cm) | |||||||

| 0 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 21.0 | 20.9 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 22.1 | 22.1 |

| 10 (68.9) | 19.2 | 19.1 | 22.7 | 23.4 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 22.2 | 22.1 |

| 15 (103.4) | 21.0 | 20.7 | 23.7 | 24.2 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 22.2 | 22.2 |

| 20 (137.9) | 21.2 | 21.0 | 24.0 | 24.9 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 22.7 | 22.8 |

| Pressure PSI (kPa) | Diameter (cm) | |||||||

| 10 (68.9) | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| 15 (103.4) | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 20 (137.9) | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Pressure PSI (kPa) | Volume (ml) | |||||||

| 10 (68.9) | 42 | - | 68 | - | 50 | - | 76 | - |

| 15 (103.4) | 62 | - | 84 | - | 57 | - | 87 | - |

| 20 (137.9) | 68 | - | 90 | - | 70 | - | 111 | - |

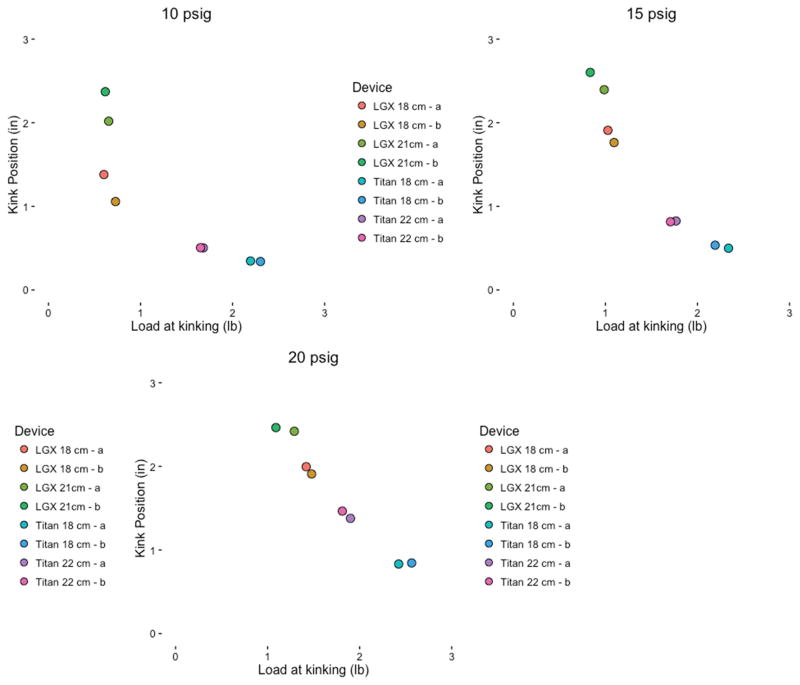

Using single longitudinal column compression load to mimic penetration, we evaluated the minimum longitudinal load required for device kinking (Figure 1). The AMS devices kinked at a lower load at all three-fill pressures than the Coloplast devices. While all devices kinked at greater longitudinal loads at increasing fill pressures, the AMS devices appeared to be more sensitive to fill pressure while the Coloplast devices were able to tolerate similar load pressures across all three fill volumes (Figure 2). The Coloplast 18cm Titan device withstood the most longitudinal load force of any device measured. We also recorded the location of device kinking during longitudinal load forces. The AMS devices kinked more proximally than the Coloplast devices which kink just behind the silicone tip (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

ADMET eXpert 7600 Single Column Testing Machine load testing of AMS 700 LGX 21(A-B) and Coloplast Titan 22(C-D).

Figure 2.

Maximum load of compression achieved at device failure and location of failure at different fill pressures. The lowest column load required to achieve kinking is reported for each cylinder represented by an individual dot.

Figure 3.

Load and location of device failure at 10, 15, and 20 PSI.

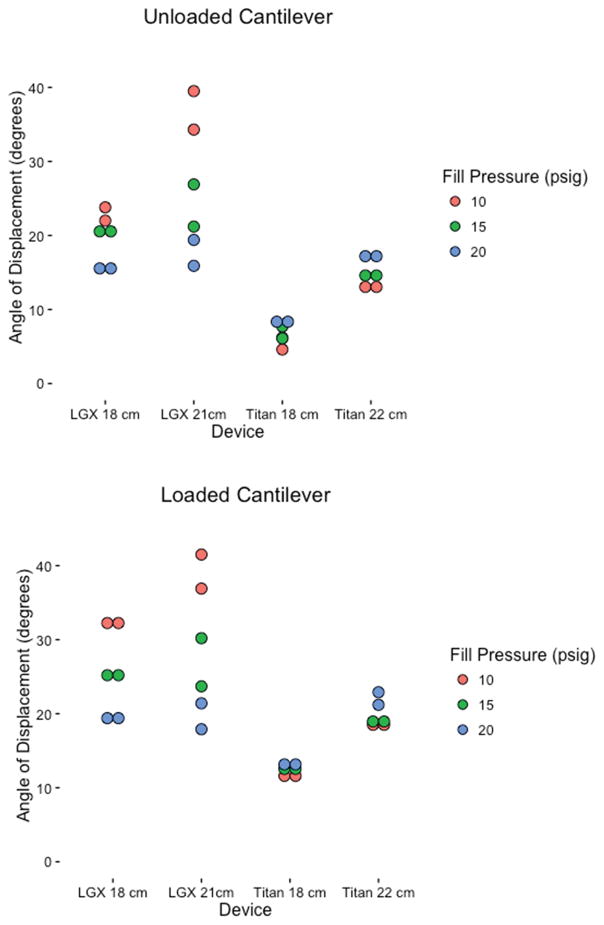

To evaluate resistance to gravitational forces, we examined horizontal rigidity using a cantilever test across all three-fill pressures (Figure 4). A lower angle of displacement represents a greater resistance to gravity. At maximal fill pressures, both the AMS and Coloplast devices had similar horizontal rigidity. However, the AMS devices tended to displace farther at lower fill volume whereas the Coloplast devices achieved near-maximal rigidity at the lowest fill pressure tested (Table 2 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Unloaded and loaded cantilever testing of the AMS 700 LGX 18cm and Coloplast Titan 18cm.

Table 2.

Displacement during unloaded and loaded modified cantilever testing at 10, 15, and 20 psig.

| Device | Boston Scientific 700 LGX | Coloplast Titan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (cm) | 18(1) | 18(2) | 21(1) | 21(2) | 18(1) | 18(2) | 22(1) | 22(2) |

| Pressure PSI (kPa) | Unloaded Angle (degrees) | |||||||

| 10 (68.9) | 22.0 | 23.8 | 34.3 | 39.5 | 6.2 | 4.6 | 12.6 | 13.5 |

| 15 (103.4) | 20.7 | 20.4 | 21.2 | 26.9 | 7.7 | 6.1 | 13.9 | 15.3 |

| 20 (137.9) | 15.7 | 15.4 | 15.9 | 19.4 | 8.9 | 7.8 | 16.8 | 17.6 |

| Pressure PSI (kPa) | Loaded Angle (degrees) | |||||||

| 10 (68.9) | 31.6 | 32.9 | 36.9 | 41.5 | 12.3 | 10.9 | 17.9 | 19.1 |

| 15 (103.4) | 25.4 | 25.0 | 23.7 | 30.2 | 12.7 | 12.4 | 18.6 | 19.3 |

| 20 (137.9) | 19.7 | 19.1 | 17.9 | 21.4 | 13.6 | 12.7 | 21.2 | 22.9 |

Figure 5.

Angle of displacement of unloaded and loaded AMS and Coloplast devices.

Discussion

The penile implant is a prosthetic designed to emulate an erection. To mechanically replicate the cylinder rigidity during penetration, we performed a longitudinal column load test. We designed device compromise as a visible kink seen in the cylinder. We report the differences in longitudinal loads required to generate a kink in four commonly used penile prosthetic devices.

To evaluate patient claims of penile curvature after time we tested horizontal rigidity of the cylinder by hanging a weight on the partially and fully inflated cylinder. At full rigidity in our testing (20 PSI) all cylinders performed admirably at lower volumes, i.e. pressure, the AMS cylinders curved in response to the cantilever.

Both the longitudinal compression and horizontal rigidity tests show that the Coloplast Titan is more resistant to longitudinal and horizontal forces especially at lower pressures (fill volumes). Importantly, the Coloplast Titan is less sensitive to changes in fill pressures, which may represent superior real-world performance as individual use varies with respect to fill volume and pressure achieved by the patient.

The results of this study highlight important differences between the two devices. The AMS 700 LGX implants became longer with increasing pressures, with the 21cm implant having the most change in cylinder length of 3.9 cm at a maximum pressure of 20 PSI. The AMS 18 cm LGX had a length change second to that of its longer counterpart at 3.1 cm at 20 PSI. The Coloplast cylinders may have minimal increase in length, although more replicates would be required to appropriately document this change. However, the Coloplast cylinders only had changes in length at higher-pressure loads.

During longitudinal pressure loading of the AMS 700 LGX devices there is a large variability in load pressures required to generate device kinking. Kink load for both AMS devices have a range of device load failure between 0.7lb at 10 PSI to 1.1–1.5lbs at 20 PSI. The Coloplast products require greater and less variable pressures to generate kinking, with pressures ranging from 1.7lbs (22 cm) to 2.2lbs (18 cm)(Figure 2).

Our study highlights that there are inherent differences in each of the IPP devices that should be considered for each patient. Traditionally, implants have been chosen based on surgeon preference upon evaluation of the stated properties of each device by the manufacturer. The AMS 700 LGX expands mostly in the longitudinal direction and less so circumferentially and was very dependent on pressures with a lower kink load than its counterpart. In-vivo testing will be required to determine if these differences can be utilized to more appropriately assign devices to the correct patient populations. Perhaps, the AMS may be troublesome for patients who have corporal fibrosis as this device appears to be less resilient to external forces. However, the AMS 700 LGX may be optimal for the man who is primarily concerned with penile length. We hypothesize that at lower pressures and volumes the Titan is superior for patient who have severe corporal fibrosis as it had a high kink load and smaller angles on the cantilever test. During the loaded and unloaded cantilever the Titan again was less pressure dependent when compared to the AMS 700 LGX and did not have cylinder displacement angles that were nearly as large. The Titan may be a superior product for men who need higher axial loading during penetration and also in men who are concerned with their phallus hanging lower after implant placement.

With respect to longitudinal compression, the Titan’s Bioflex material appears to be more resilient ex-vivo. Admittedly, the compression load required to compress each device may be above what many patients experience during sexual intercourse. Nevertheless, our data suggest that patients who may not be motivated or capable of filling the device to higher volumes may benefit from a Coloplast device as these are less dependent on filling pressures to maintain longitudinal rigidity. Patients who have partners that require increased pressure to achieve penetration may also benefit from the increased longitudinal strength of the Coloplast devices especially at lower pressures.

This study has several key strengths and limitations that must be addressed. We analyzed each cylinder individually as opposed to the entire device as we believed this setup would allow for clear endpoints with less variability. These tests were performed ex-vivo, which does not account for the anatomical factors that may either enhance or negate the differences in device performance. Additional anatomical constraints imposed by the tunica albuginea are likely to change the dynamics of these devices. Future work on the variation and biomechanical properties of the tunica albuginea and surrounding tissues will be important in developing a device that leverages our understanding about these structures.12 Our study was also limited by the number of devices per manufacturer and number of devices tested. This study was funded by the principal author and not funded by industry. Laboratory time and the biomechanical engineering were purchased from Rice University. The implants were purchased at a discount from the manufacturers or third party vendors. These cost constraints caused limitation of the number of pump/cylinder assemblies purchased from the manufacturers. It also created the scenario that only the 18 cm cylinder was the same length from both manufacturers. It would also have been ideal to test the AMS CX cylinders and other cylinder sizes of the devices. The AMS CX is likely to have more rigidity than the AMS 700 LGX providing a more similar comparison between the two manufacturer’s devices. Hopefully, publication of our initial findings with a limited number of cylinder sizes will stimulate a more extensive study.

Last, we chose to test each device at 10, 15, and 20 PSI as we felt these pressures represented similar rigidity experienced in-vivo. However, these pressures required supraphysiological fill volumes. We hypothesize that additional in-vivo dynamics including the added rigidity and support provided by the tunica albuginea may allow the device to achieve similar fill pressures at lower fill volumes.

Our results suggest that differences in longitudinal load response during penetration are more likely due to differences in manufacturer design and materials than due to the size of the device itself. This study is strengthened by the methodology used to measure the response to longitudinal and horizontal loads. Investigators were blinded to manufacturers during testing and had no prior experience with penile prostheses, which limited their ability to identify which manufacturer produced which device. The biomechanical testing is performed on a validated platform that provides accurate and precise data.

These data support that inherent differences exist between IPPs that surgeons must consider when treating erectile dysfunction. We plan to perform additional biomechanical testing both ex-vivo and in-vivo to further characterize the strengths of each device to help guides surgeons as to which patients may benefit from each prosthetic device.

Conclusions

This is the first biomechanical comparison of the AMS 700 LGX to the Coloplast Titan. Inherent differences exist between the two IPP devices with respect to their ability to resist both longitudinal and horizontal forces. The Coloplast Titan was superior to the AMS 700 LGX in resisting longitudinal and horizontal forces in this study. The AMS implant’s performance was more dependent on fill pressures suggesting the potential for greater variability in patient experience.

References

- 1.Chung E, Solomon M, DeYoung L, Brock GB. Comparison between AMS 700 CX and Coloplast Titan inflatable penile prosthesis for Peyronie’s disease treatment and remodeling: clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10:2855–60. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakky TS, Wang R, Henry GD. The evolution of the inflatable penile prosthetic device and surgical innovations with anatomical considerations. Current urology reports. 2014;15:410. doi: 10.1007/s11934-014-0410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry GD. Historical review of penile prosthesis design and surgical techniques: part 1 of a three-part review series on penile prosthetic surgery. The journal of sexual medicine. 2009;6:675–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulcahy JJ. The Development of Modern Penile Implants. Sexual medicine reviews. 2016;4:177–89. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson SK, Henry GD, Delk JR, Jr, Cleves MA. The mentor Alpha 1 penile prosthesis with reservoir lock-out valve: effective prevention of auto-inflation with improved capability for ectopic reservoir placement. The Journal of urology. 2002;168:1475–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolter CE, Hellstrom WJ. The hydrophilic-coated inflatable penile prosthesis: 1-year experience. The journal of sexual medicine. 2004;1:221–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.04032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carson CC, 3rd, Mulcahy JJ, Harsch MR. Long-term infection outcomes after original antibiotic impregnated inflatable penile prosthesis implants: up to 7.7 years of followup. The Journal of urology. 2011;185:614–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung PH, Morey AF, Tausch TJ, Simhan J, Scott JF. High submuscular placement of urologic prosthetic balloons and reservoirs: 2-year experience and patient-reported outcomes. Urology. 2014;84:1535–40. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milbank AJ, Montague DK, Angermeier KW, Lakin MM, Worley SE. Mechanical failure of the American Medical Systems Ultrex inflatable penile prosthesis: before and after 1993 structural modification. The Journal of urology. 2002;167:2502–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coloplast. Titan® The Serious Solution. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pescatori ES, Goldstein I. Intraluminal device pressures in 3-piece inflatable penile prostheses: the “pathophysiology” of mechanical malfunction. The Journal of urology. 1993;149:295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reed-Maldonado AB, Lue TF. Learning Penile Anatomy to Improve Function. The Journal of urology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]