We identify a strong association between long-term acetaminophen use and offspring ADHD that is not explained by indications of use or familial ADHD.

Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To estimate the association between maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and of paternal use before pregnancy with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring while adjusting for familial risk for ADHD and indications of acetaminophen use.

METHODS:

Diagnoses were obtained from the Norwegian Patient Registry for 112 973 offspring from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, including 2246 with ADHD. We estimated hazard ratios (HRs) for an ADHD diagnosis by using Cox proportional hazard models.

RESULTS:

After adjusting for maternal use of acetaminophen before pregnancy, familial risk for ADHD, and indications of acetaminophen use, we observed a modest association between any prenatal maternal use of acetaminophen in 1 (HR = 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.96–1.19), 2 (HR = 1.22; 95% CI 1.07–1.38), and 3 trimesters (HR = 1.27; 95% CI 0.99–1.63). The HR for more than 29 days of maternal acetaminophen use was 2.20 (95% CI 1.50–3.24). Use for <8 days was negatively associated with ADHD (HR = 0.90; 95% CI 0.81–1.00). Acetaminophen use for fever and infections for 22 to 28 days was associated with ADHD (HR = 6.15; 95% CI 1.71–22.05). Paternal and maternal use of acetaminophen were similarly associated with ADHD.

CONCLUSIONS:

Short-term maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy was negatively associated with ADHD in offspring. Long-term maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy was substantially associated with ADHD even after adjusting for indications of use, familial risk of ADHD, and other potential confounders.

What’s Known on This Subject:

In previous studies, researchers have identified an association between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring. Maternal use of acetaminophen is associated with impulsivity; hence, it is unknown if the association is due to indications of use or familial risk for ADHD.

What This Study Adds:

After adjusting for familial risk for ADHD, indications of use, and acetaminophen use before pregnancy, long-term acetaminophen use during pregnancy is related to more than a twofold increase in risk for offspring ADHD.

Acetaminophen is the recommended medication for pregnant women with fever or pain and is widely used during pregnancy. Reports have suggested that acetaminophen is used by ∼65% to 70% of pregnant women in the United States and by ∼50% to 60% of pregnant women in western and northern Europe.1,2 Acetaminophen crosses the placenta and can be traced in the infant’s urine after prenatal exposure.3 In 2013, researchers conducting a sibling comparison in a large, population-based Norwegian birth cohort study suggested that prenatal acetaminophen use for 28 or more days was associated with poorer motor and communicational development and externalizing problems (ie, inattentiveness and aggression) in offspring.4 The following year, researchers conducting a large Danish birth cohort study found an association between prenatal acetaminophen use and both a clinical attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis and ADHD symptoms in offspring5; later, researchers in other studies related prenatal acetaminophen use to rating scales of disinhibited behavior.6,7

The Danish study5 had several strengths, including prospective assessment, a large sample size, and a number of relevant covariates. It also had some important limitations, especially possible residual confounding.8 Acetaminophen is recommended for pregnant women with fever and pain; it is also used for a wide array of other inflammatory conditions during pregnancy. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the presence of some of these conditions during pregnancy (eg, fever, inflammation, and autoimmunity) are associated with increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring.9–12 To investigate potential adverse effects of acetaminophen on fetal development, it is therefore essential to allow for the potential influence of such underlying conditions. We have previously found that an impulsive personality is associated with acetaminophen use during pregnancy.13 It is therefore possible that acetaminophen use during pregnancy could be influenced by familial factors (including genetic influences) that may also influence the risk of offspring ADHD. It is therefore important to adjust for parental symptoms of ADHD.

If the association between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and offspring ADHD is due to unobserved maternal factors (eg, impulsive personality traits13), we would expect use before pregnancy to be no less associated with offspring ADHD than use during pregnancy. Prepregnancy use therefore serves as a negative control for the specificity of the gestational effect.14

If the association is due to unobserved familial factors (eg, genetic factors), paternal use of acetaminophen may also be associated with ADHD in a way similar to maternal use of acetaminophen. However, acetaminophen and endocrine disruptors have been shown to have potential for transgenerational disease transmission effects in mouse models via male germ-line epigenetic effects, and endocrine disruption effects of acetaminophen have been shown in the human testis.15,16 It is therefore important to estimate the effect of paternal prepregnancy use.

In the current study, we used data from a large, prospective, population-based birth cohort from Norway to examine whether acetaminophen use during pregnancy was associated with ADHD in the offspring after adjusting for potential confounders. In contrast to researchers in previous studies, we were able to adjust for indications of acetaminophen use and parental symptoms of ADHD. We were furthermore able to analyze maternal use of acetaminophen before pregnancy as a negative control17 and to estimate the effect of paternal use before pregnancy on offspring ADHD.

Methods

Sample

Data were drawn from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.18 Invitations were sent by mail to pregnant women in Norway in connection with the routine ultrasound examination offered at the local hospitals around pregnancy week 18, and 40.6% of the invited women consented to participate. The cohort includes 114 744 children born between 1999 and 2009, 95 242 mothers, and 75 217 fathers from all over Norway. The establishment and data collection in MoBa has obtained a license from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and approval from the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics. The current study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics. Self-report questionnaires were sent to the mothers and fathers at approximately 18 weeks of gestation and to mothers later in pregnancy and after delivery. We used information from maternal questionnaires when children were 6 months old, 1.5 years old, and 3 years old in version 9 of the quality-assured MoBa data files. We excluded 1283 study subjects who died or emigrated during childhood and 488 subjects without a recorded date of birth in the Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Our final sample comprised the eligible 112 973 children and their parents.

Measure of ADHD

We obtained information about children’s ADHD diagnosis from the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR).19 Since 2008, all government-owned and government-financed hospitals and outpatient clinics mandatorily report individual-level International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision diagnoses20 to NPR to receive financial reimbursement. By using individual personal identification numbers, diagnostic information from NPR was linked to MoBa. Thus, all MoBa children registered with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder (F90.0, F90.1, F90.8, or F90.9) between 2008 and 2014 were identified and regarded as having ADHD. Hyperkinetic disorder requires the combination of inattentive and hyperactive symptoms, and as a result, hyperkinetic disorder is a subtype nested within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition classification of ADHD.21 In comparison with ADHD, hyperkinetic disorder is characterized by a higher proportion of patients with impaired language and motor development.22 Two cases were excluded from the analyses because of an F90 diagnosis before the age of 3.

Prenatal Use of Acetaminophen

Information on acetaminophen use was obtained through MoBa questionnaires. Acetaminophen use was available from 2 prenatal and 1 postnatal questionnaires. At week 18, week 30, and 6 months postpartum, the mothers were asked to report on 77, 32, and 19 different medical conditions, respectively. The mothers reported details on medication use specifically for each medical condition. In addition, at each time point, the mothers listed names of any additional medications used. For each indication, the mother could name the medication taken in an open textbox and specify the following exposure windows: 6 months before gestation; gestational weeks 0 to 4, 5 to 8, 9 to 12, and ≥13 (until completion of the first questionnaire); 13 to 16, 17 to 20, 21 to 24, 25 to 28, and ≥29 (until completion of the second questionnaire); and ≥30 (until birth), 0 to 3 months postpartum, and 4 to 6 months postpartum. Use 6 months before gestation was reported on 53 of the 77 indications reported at week 18. In addition, mothers were asked to report all other medication use for all exposure windows in all questionnaires. Questionnaires can be found at www.fhi.no.

Number of days was reported as a total across all exposure windows in each questionnaire. The percentage of indications relating to acetaminophen use having 0, 1, or ≥2 comedications were 88.9%, 10.0%, and 1.1%, respectively. Fathers filled out a separate questionnaire at gestational week 18. Therein, they reported their medication use for the last 6 months before pregnancy. We classified and grouped medication exposure according to the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification System developed by the World Health Organization.23 Acetaminophen exposure was defined as using a drug with the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical code N02BE01.

Covariates

On the basis of previous literature, the following covariates were considered potential confounders: parental symptoms of ADHD (in MoBa, these are measured by the 6-item World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale screener24 measuring risk for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition classification of ADHD), maternal self-reported alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal self-reported daily smoking during pregnancy, symptoms of anxiety and depression at the 18th and 30th week of gestation (in MoBa, this is measured by the 5- and 8-item short version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25),25,26 maternal education, marital status, BMI at the 18th week of gestation, maternal age, parity, birth year centered to 1999, and birth year squared to adjust for nonlinear cohort effects. Maternal age and parity were obtained from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway.27 In addition, we assessed 128 medical conditions at the 17th week and 30th week of gestation and at 6 months postpartum. Acetaminophen was used for 96 of these indications.

Statistical Analyses

The associations between acetaminophen use and offspring ADHD were examined in Cox proportional hazard models with the offspring’s age in months as the time metric. Offspring were defined as being at risk from 3 years of age and were followed to the time of ADHD diagnosis or censored at December 31, 2014. To replace missing values on self-reported covariates, we used multiple imputation with 50 imputations28.

For the analysis in which we investigated duration of acetaminophen use, we used the indication nested within each mother as our observational unit. For example, a mother having used acetaminophen for 5 out of the 128 possible indications at any time point during pregnancy contributed 5 units in the analyses (ie, 1 for each indication of use). Because the number of days was reported as a total across all exposure windows in each questionnaire, we adjusted the analyses of number of days used for number of comedications, use before pregnancy, and use after pregnancy within each indication. We grouped the effects of use across types of indications (ie, fever and infections, pain conditions, and indication not specified). We used a stratified Cox model to account for duration of acetaminophen use, with indications as strata. To account for clustering of indications within mothers, we used robust standard errors. We used Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for all analyses.29

Results

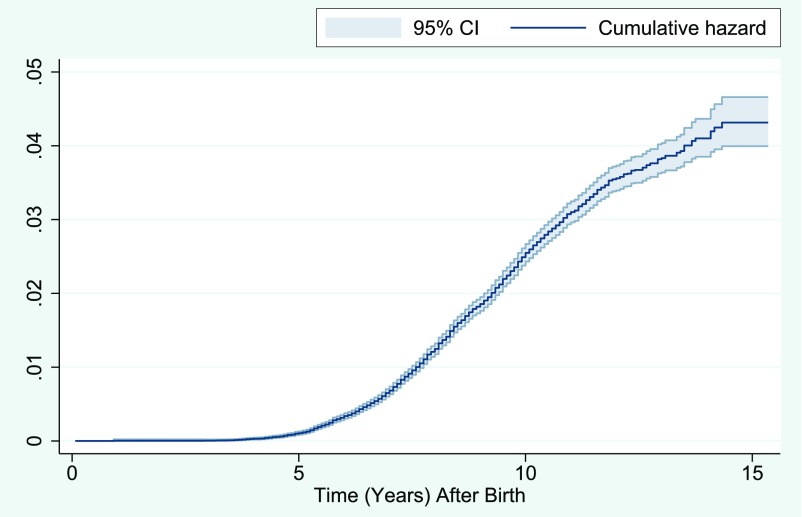

The study population included 112 973 children, of whom 2246 had been diagnosed with ADHD. In Fig 1, we present the estimated cumulative number of expected ADHD events across age. We estimated that ∼4% of children in MoBa will have an ADHD diagnosis at the age of 13 (Fig 1). Fifty-two thousand seven-hundred and seven (46.7%) women used acetaminophen during pregnancy (Table 1). Twenty-seven percent used acetaminophen in 1 trimester, 16% in 2 trimesters, and 3.3% in all 3 trimesters. Maternal preconceptional use and use in the first trimester was approximately equally associated (r = 0.49) with use in the first and second trimester (r = 0.56) and use in the second and third trimester (r = 0.49) (Supplemental Table 4). Paternal use was associated with maternal preconceptional use and use during pregnancy (r = 0.18–0.10) (Supplemental Table 4).

FIGURE 1.

The figure depicts the Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard estimate and the estimated proportion of children receiving an ADHD diagnosis by age after birth.

TABLE 1.

HRs for ADHD Diagnosis According to Maternal Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy in 112 973 Offspring

| Complete Cases | Estimated Data by Multiple Imputation | HRs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| n | Total n | % | n | % | Adjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted (95% CI) | ||

| Acetaminophen use 6 mo before pregnancy | 27 584 | 104 084 | 26.5 | 29 931 | 26.5 | 1.04 | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 0.92 (0.82–1.02) | 0.95 (0.85–1.06) |

| Paternal acetaminophen use | 11 119 | 61 543 | 18.1 | 20 151 | 17.8 | 1.34 | 1.31 (1.12–1.53) | 1.26 (1.08–1.48) | 1.27 (1.08–1.49) |

| Acetaminophen use during pregnancy | |||||||||

| Never used during pregnancy | 45 615 | 93 216 | 48.9 | 60 266 | 53.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Ever used during pregnancy | 47 601 | 93 216 | 51.1 | 52 707 | 46.7 | 1.26 | 1.25 (1.14–1.37) | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | 1.12 (1.02–1.24) |

| Any 1 trimester | 23 244 | 85 854 | 27.1 | 30 610 | 27.1 | 1.17 | 1.17 (1.05–1.30) | 1.13 (1.01–1.27) | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) |

| First trimester only | 7448 | 85 854 | 8.7 | 9282 | 8.2 | 1.15 | 1.15 (0.97–1.36) | 1.14 (0.97–1.36) | 1.12 (0.94–1.32) |

| Second trimester only | 14 688 | 85 854 | 17.1 | 19 927 | 17.6 | 1.17 | 1.17 (1.03–1.33) | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) |

| Third trimester only | 1108 | 85 854 | 1.3 | 1401 | 1.2 | 1.21 | 1.21 (0.80–1.83) | 1.12 (0.74–1.69) | 1.12 (0.75–1.67) |

| Any 2 trimesters | 13 698 | 85 854 | 16.0 | 18 379 | 16.3 | 1.39 | 1.39 (1.23–1.60) | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) |

| Both first and second trimesters | 11 536 | 85 854 | 13.4 | 15 254 | 13.5 | 1.37 | 1.38 (1.20–1.60) | 1.32 (1.15–1.51) | 1.21 (1.06–1.39) |

| Both second and third trimesters | 1653 | 85 854 | 1.9 | 2389 | 2.1 | 1.46 | 1.46 (1.06–2.00) | 1.30 (0.95–1.78) | 1.20 (0.87–1.66) |

| Both first and third trimesters | 509 | 85 854 | 0.6 | 737 | 0.7 | 1.44 | 1.45 (0.83–2.52) | 1.35 (0.77–2.34) | 1.34 (0.77–2.34) |

| All 3 trimesters | 2908 | 85 854 | 3.4 | 3718 | 3.3 | 1.46 | 1.46 (1.15–1.24) | 1.34 (1.05–1.71) | 1.27 (0.99–1.63) |

Two thousand two hundred and forty six children were diagnosed with ADHD by December 31, 2014. All estimates are adjusted for birth year, model 2 is furthermore adjusted for parental ADHD symptoms, and model 3 is furthermore adjusted for alcohol use during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy, maternal education, marital status, BMI at 17th week of gestation, maternal age, and parity.

Offspring prenatally exposed to acetaminophen had an increased unadjusted hazard rate of ADHD of 17%, 39%, and 46% after 1, 2, and 3 trimesters of exposure, respectively (Table 1). These associations were not attenuated when we adjusted for maternal and paternal use before pregnancy (model 1), but they were slightly lower after we adjusted for parental symptoms of ADHD (model 2). In model 3, we adjusted for a range of potential confounders Supplemental Table 5), and the hazard ratios (HRs) for the associations between 1, 2, and 3 trimesters of prenatal acetaminophen exposure were 1.07 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.96–1.19), 1.22 (95% CI 1.07–1.38), and 1.27 (95% CI 0.99–1.63), respectively. The negative control, maternal preconceptual use of acetaminophen, had no effect on offspring ADHD. Paternal preconceptional use had no weaker effect than maternal use during pregnancy (Table 1).

In Table 2, we present the HRs for offspring ADHD by number of days of prenatal acetaminophen exposure, adjusted for each indication of use by stratification. We found that use of acetaminophen <7 days was negatively associated with offspring ADHD. For use >7 days, the HR for offspring ADHD increased with the number of days exposed. Prenatal use of acetaminophen for 29 or more days was associated with a substantially increased hazard rate of ADHD (HR = 2.20; 95% CI 1.50–3.24), even after adjusting for indications of use by stratification (Supplemental Table 6). The associations with use of 29 days or more did not differ across groups of indications (HR = 2.13–2.56). Acetaminophen use for fever and infections for 22 to 28 days was strongly associated with ADHD (HR = 6.15; 95% CI 1.71–22.05). Associations between paternal preconceptional use of acetaminophen and ADHD are presented in Table 3. Short-term paternal use was not negatively associated with ADHD (HR = 1.10; 95% CI 0.92–1.30); paternal use for 29 days or more was as strongly associated with ADHD (HR = 2.06; 95% CI 1.36–3.13) as the corresponding maternal prenatal use.

TABLE 2.

HRs for Offspring ADHD by Number of Days of Maternal Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy

| All Indications | Groups of Indications for Acetaminophen Use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever and Infections | Pain Conditions | Indication Not Specified | ||||||

| No. of Mothers Reporting Each Exposure Duration / Overall No. of Observations of Use per Exposure Duration |

Adjusted HRa (95% CI) |

No. of Mothers Reporting Each Exposure Duration / Overall No. of Observations of Use per Exposure Duration |

Adjusted HRa

(95% CI) |

No. of Mothers Reporting Each Exposure Duration / Overall No. of Observations of Use per Exposure Duration |

Adjusted HRa

(95% CI) |

No. of Mothers Reporting Each Exposure Duration / Overall No. of Observations of Use per Exposure Duration |

Adjusted HRa

(95% CI) |

|

| No use | 103 017 | 1.00 | 84 304 | 1.00 | 75 019 | 1.00 | 4606 | 1.00 |

| 1 153 338 | Reference | 216 206 | Reference | 180 288 | Reference | 4639 | Reference | |

| 1–7 d | 36 899 | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 8752 | 0.90 (0.75–1.09) | 10 335 | 0.89 (0.76–1.04) | 19 154 | 1.30 (0.98–1.73) |

| 53 667 | 10 864 | 12 064 | 21 796 | |||||

| 8–14 d | 6434 | 1.18 (0.98–1.42) | 1021 | 1.02 (0.55–1.89) | 2653 | 1.12 (0.83–1.50) | 1949 | 1.96 (1.36–2.82) |

| 7923 | 1185 | 2925 | 2020 | |||||

| 15–21 d | 2003 | 1.35 (1.00–1.81) | 185 | 0.98 (0.24–3.95) | 1045 | 1.43 (0.96–2.14) | 441 | 1.79 (0.95–3.35) |

| 2369 | 200 | 1147 | 447 | |||||

| 22–28 d | 253 | 1.60 (0.70–3.69) | 16 | 6.15 (1.71–22.05) | 133 | 1.08 (0.34–3.39) | 61 | — |

| 283 | 17 | 138 | 62 | |||||

| 29 or more d | 1034 | 2.20 (1.50–3.24) | 72 | 2.40 (0.34–16.78) | 609 | 2.56 (1.54–4.25) | 200 | 2.13 (0.88–5.15) |

| 1395 | 75 | 772 | 212 | |||||

—, not applicable.

Adjusted for year of birth, maternal age, parity, comedication within each indication of use, acetaminophen use first 6 months before pregnancy within each indication of use (only reports on first trimester are adjusted), and acetaminophen use in the first 6 months postpartum within each indication of use (only reports on last trimester are adjusted). Two thousand two hundred and forty six children were diagnosed with ADHD by December 31, 2014.

TABLE 3.

HRs for Offspring ADHD by Number of Days of Paternal Acetaminophen Use 6 Months Before Pregnancy

| No. of Fathers Reporting Each Category | HRa | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No use | 64 348 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 1–7 d | 8887 | 1.10 | (0.92–1.30) |

| 8–28 d | 1079 | 1.81 | (1.26–2.60) |

| 29 or more d | 657 | 2.06 | (1.36–3.13) |

Adjusted for year of birth, paternal age, and parity.

Discussion

We found maternal prenatal acetaminophen use to be associated with a higher hazard rate for offspring ADHD, supporting the findings of Liew et al13 based on Danish registry data. Liew et al13 did not, however, control for the indications for use or ADHD-related familial factors. In our study, the association persisted after adjusting for acetaminophen use before pregnancy and for parental symptoms of ADHD. We had the advantage of having medication data separately for each indication, allowing us to account for confounding by each indication in a stratified model. Offspring prenatally exposed to acetaminophen for 29 days or more had a twofold HR for receiving a clinical diagnosis of ADHD from specialist health services. This estimate was the same regardless of indication (ie, fever and infections or pain conditions). Maternal use of acetaminophen for <8 days was negatively associated with ADHD. The association between paternal preconceptional acetaminophen use and ADHD was similar to the association between maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and ADHD.

The considerable increased rate of ADHD associated with long-term prenatal exposure to acetaminophen (ie, >29 days) is in line with the findings of Brandlistuen et al,4 who also found small associations for short-term use and large associations for long-term use among discordant siblings in a subset of MoBa. Liew et al13 also found stronger associations by increasing number of weeks exposed.

ADHD is highly familial in both children and adults.30 We have previously found that acetaminophen use during pregnancy was associated with impulsive personality traits in mothers.13 Therefore, our ability to adjust for parental symptoms of ADHD represents a considerable improvement compared to previous study designs. With our analyses, we showed that the association between maternal acetaminophen use and ADHD did not appear to be strongly confounded by common familial (eg, genetic) factors for ADHD and use of acetaminophen. Researchers in previous studies have also suggested common familial risk factors for maternal depression and offspring disruptive behavior.31,32 We examined this by adjusting for maternal symptoms of depression, but the association remained.

Even after adjusting for indications of use, there was still an association (HR = 2.20; 95% CI 1.50–3.24) between long-term prenatal acetaminophen exposure and childhood ADHD. This estimate was similar across several indications for acetaminophen use (fever, infections, and pain conditions). This indicates that putative confounding factors for long-term acetaminophen use and ADHD are not related to the recorded indications but are related to unmeasured factors.

Maternal preconceptional use was not associated with ADHD. This is in line with a recent study in which researchers found no effect of maternal postnatal acetaminophen use on maternal reports of behavior problems.7 Furthermore, we found that maternal preconceptional use was as associated with use during the first trimester as use across 2 trimesters. This supports the employment of maternal preconceptional use as a negative (or specificity) control and is consistent with a causal link.

The mechanics of the ADHD effect of paternal acetaminophen use before pregnancy are unclear. It may be due to male germ-line epigenetic effects as described in endocrine disruption effects of acetaminophen on the human testis.15,16

At least 3 plausible hypotheses are proposed to explain the association between maternal acetaminophen use and ADHD. First, neonatal exposure to acetaminophen changes the levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor in mice and results in altered behavior, lowered fear responses, and reduced learning abilities in adulthood.33 Brain-derived neurotropic factor promotes neuronal survival and regulates cell migration, axonal and dendritic outgrowth, and formation of synapses.33–35 Second, acetaminophen could interfere with maternal hormones (such as thyroid hormones and sex hormones) that are related to fetal brain development.5,15,36–39 Third, acetaminophen could interrupt brain development by induction of oxidative stress, leading to neuronal death.4,40–42 All of these 3 putative mechanisms can be further tested in experimental animal studies.

Our finding that acetaminophen use for <8 days is negatively associated with offspring ADHD indicates that the antipyretic effect could be beneficial with regard to fetal development.11,12

We address 3 limitations that could have biased the results. First, although we were able to stratify on each indication of use, long-term use within each indication is likely to represent a more severe form of the disorder. We were not able to adjust for the severity of each condition indicative of acetaminophen use. Second, the ADHD diagnosis was not validated in a research clinic but was based on a diagnosis registered by a specialist in the Norwegian health care system. Finally, young parents and parents who were smokers are underrepresented in MoBa,43 which may limit generalization of results to all children. It has, however, previously been shown that although estimates of frequencies and means were biased because of selective participation, selected exposure-outcome associations did not differ between MoBa participants and the general Norwegian population.43–45

Conclusions

Long-term maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy is associated with ADHD in offspring. This holds true even after adjusting for potential confounders, including parental symptoms of ADHD and indications of acetaminophen use. Although maternal preconceptional use was substantially correlated with use during pregnancy, only use during pregnancy was associated with ADHD. However, given that paternal use of acetaminophen is also associated with ADHD, the causal role of acetaminophen in the etiology of ADHD can be questioned. We do not provide definitive evidence for or against a causal relation between maternal use of acetaminophen and ADHD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ragna Bugge Askeland for assisting in the registry linkage and Ragnhild Eskeland for interpretation of the paternal effects. We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who take part in this ongoing cohort study.

Glossary

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- MoBa

Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study

- NPR

Norwegian Patient Registry

Footnotes

Dr Ystrom designed the study, conducted analyses, and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Gustavson, Brandlistuen, Susser, Davey Smith, Stoltenberg, Surén, Håberg, Hornig, Lipkin, Nordeng, and Reichborn-Kjennerud contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Dr Knudsen contributed substantially in the acquisition of data by coordinating the registry linkage and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Dr Magnus contributed substantially in the acquisition of data by leading the data collection of the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the European Research Council Starting Grant “DrugInPregnancy” (grant 678033) and the Health Sciences and Biology Programme at the Norwegian Research Council (grant 231105). The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study is supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (contract N01-ES-75558), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant 1 U01 NS 047537-01 and grant 2 U01 NS 047537-06A1). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2017-2703.

References

- 1.Lupattelli A, Spigset O, Twigg MJ, et al. . Medication use in pregnancy: a cross-sectional, multinational web-based study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werler MM, Mitchell AA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Honein MA. Use of over-the-counter medications during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3, pt 1):771–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy G, Garrettson LK, Soda DM. Letter: evidence of placental transfer of acetaminophen. Pediatrics. 1975;55(6):895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: a sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liew Z, Ritz B, Rebordosa C, Lee PC, Olsen J. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson JM, Waldie KE, Wall CR, Murphy R, Mitchell EA; ABC Study Group . Associations between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and ADHD symptoms measured at ages 7 and 11 years. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stergiakouli E, Thapar A, Davey Smith G. Association of acetaminophen use during pregnancy with behavioral problems in childhood: evidence against confounding. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(10):964–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper M, Langley K, Thapar A. Antenatal acetaminophen use and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an interesting observed association but too early to infer causality. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):306–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu G, Jing J, Bowers K, Liu B, Bao W. Maternal diabetes and the risk of autism spectrum disorders in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):766–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SW, Zhong XS, Jiang LN, et al. . Maternal autoimmune diseases and the risk of autism spectrum disorders in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Brain Res. 2016;296:61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werenberg Dreier J, Nybo Andersen AM, Hvolby A, Garne E, Kragh Andersen P, Berg-Beckhoff G. Fever and infections in pregnancy and risk of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the offspring. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(4):540–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreier JW, Andersen AMN, Berg-Beckhoff G. Systematic review and meta-analyses: fever in pregnancy and health impacts in the offspring. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/3/e674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ystrom E, Vollrath ME, Nordeng H. Effects of personality on use of medications, alcohol, and cigarettes during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(5):845–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology. 2010;21(3):383–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert O, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Lesné L, et al. . Paracetamol, aspirin and indomethacin display endocrine disrupting properties in the adult human testis in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1890–1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazaud-Guittot S, Nicolas Nicolaz C, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, et al. . Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin induce endocrine disturbances in the human fetal testis capable of interfering with testicular descent. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):E1757–E1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keyes KM, Smith GD, Susser E. Commentary: smoking in pregnancy and offspring health: early insights into family-based and ‘negative control’ studies? Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(5):1381–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, et al. . Cohort profile update: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(2):382–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norwegian Directorate of Health. Norwegian Patient Registry. 2016. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/english/norwegian-patient-registry. Accessed July 1, 2016

- 20.World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10): 10th Rev. Vol 2 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonuga-Barke EJS, Taylor E. ADHD and hyperkinetic disorder In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor E, eds. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 6th ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015:738–756 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor E, Schachar R, Thorley G, Wieselberg HM, Everitt B, Rutter M. Which boys respond to stimulant medication? A controlled trial of methylphenidate in boys with disruptive behaviour. Psychol Med. 1987;17(1):121–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System with defined daily doses (ATC/DDD). 2015. Available at: www.who.int/classifications/atcddd/en/. Accessed Nov 16, 2015

- 24.Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. . The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tambs K, Moum T. How well can a few questionnaire items indicate anxiety and depression? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87(5):364–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, Rognerud M. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57(2):113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irgens LM. The medical birth registry of Norway. Epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(6):435–439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin Donald B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Vol 81 Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 29.StataCorp Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsson H, Chang Z, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P. The heritability of clinically diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Psychol Med. 2014;44(10):2223–2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silberg JL, Maes H, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental influences on the transmission of parental depression to children’s depression and conduct disturbance: an extended children of twins study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(6):734–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh AL, D’Onofrio BM, Slutske WS, et al. . Parental depression and offspring psychopathology: a children of twins study. Psychol Med. 2011;41(7):1385–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viberg H, Eriksson P, Gordh T, Fredriksson A. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) administration during neonatal brain development affects cognitive function and alters its analgesic and anxiolytic response in adult male mice. Toxicol Sci. 2014;138(1):139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui Q. Actions of neurotrophic factors and their signaling pathways in neuronal survival and axonal regeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;33(2):155–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colborn T. Neurodevelopment and endocrine disruption. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(9):944–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howdeshell KL. A model of the development of the brain as a construct of the thyroid system. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(suppl 3):337–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ. Androgens, brain, and behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(8):974–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghassabian A, Bongers-Schokking JJ, Henrichs J, et al. . Maternal thyroid function during pregnancy and behavioral problems in the offspring: the generation R study. Pediatr Res. 2011;69(5, pt 1):454–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dringen R. Metabolism and functions of glutathione in brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62(6):649–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghanizadeh A. Acetaminophen may mediate oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in autism. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78(2):351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Posadas I, Santos P, Blanco A, Muñoz-Fernández M, Ceña V. Acetaminophen induces apoptosis in rat cortical neurons. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, et al. . Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(6):597–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gustavson K, Borren I. Bias in the study of prediction of change: a Monte Carlo simulation study of the effects of selective attrition and inappropriate modeling of regression toward the mean. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gustavson K, von Soest T, Karevold E, Røysamb E. Attrition and generalizability in longitudinal studies: findings from a 15-year population-based study and a Monte Carlo simulation study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.