Abstract

The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome was determined for two cultivars of Brassica rapa. After determining the sequence of a Chinese cabbage variety, ‘Oushou hakusai’, the sequence of a mizuna variety, ‘Chusei shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna’, was mapped against the sequence of Chinese cabbage. The precise sequences where the two varieties demonstrated variation were ascertained by direct sequencing. It was found that the mitochondrial genomes of the two varieties are identical over 219,775 bp, with a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) between the genomes. Because B. rapa is the maternal species of an amphidiploid crop species, Brassica juncea, the distribution of the SNP was observed both in B. rapa and B. juncea. While the mizuna type SNP was restricted mainly to cultivars of mizuna (japonica group) in B. rapa, the mizuna type was widely distributed in B. juncea. The finding that the two Brassica species have these SNP types in common suggests that the nucleotide substitution occurred in wild B. rapa before both mitotypes were domesticated. It was further inferred that the interspecific hybridization between B. rapa and B. nigra took place twice and resulted in the two mitotypes of cultivated B. juncea.

Keywords: complete mitochondrial genome, intraspecific differentiation, single nucleotide polymorphism, Brassica rapa, Brassica juncea

Introduction

Analyses of the plant mitochondrial genome, especially DNA sequences, reveal not only phylogenetic relationships among plant species, but also intraspecific differentiation of the cytoplasm (Darracq et al. 2011, Fujii et al. 2010, Kubo and Newton 2008). In six Brassica crop species, Brassicaceae, of which three are diploids and three are amphidiploids derived from all cross combinations of the three diploids (U 1935), data on intraspecific differentiation of mitochondrial genome sequences have been accumulated rapidly. Yamagishi et al. (2014) determined the complete genome sequences (232,145 bp; AP012989) and found an insertion/deletion (indel) variation in Brassica nigra (2n = 16, BB genome), while Yang et al. (2016) reported a mitochondrial genome size of 232,407 bp (KP030753) for B. nigra. Brassica oleracea (2n = 18, CC genome) also exhibited intraspecific differentiation of the mitochondrial genome. Chang et al. (2011) reported that the genome sequence consisted of 360,271 bp (JF920286). On the other hand, Tanaka et al. (2014) found that a cabbage variety, ‘Fujiwase’, possesses a mitochondrial genome of 219,952 bp (AP012988). Further, Grewe et al. (2014) demonstrated that the mitochondrial genome of cauliflower is 219,962 bp. The report of Chang et al. (2011) showed an extremely large difference in genome size from the other two within B. oleracea. In comparison with those two species, there has been only one report (Chang et al. 2011) on another diploid Brassica crop, B. rapa (2n = 20, AA genome).

B. rapa is cultivated worldwide for utilization in various ways (Prakash and Hinata 1980). Besides fodder turnips cultivated in Europe and oil seeds grown mainly in Southern Asia (toria and sarson), vegetable turnips and leafy vegetables have been developed in East Asia. Chinese cabbage (pekinensis group), which has tightly overlapping large leaves, is one of the major vegetables in China, Korea and Japan, whereas mizuna (japonica group) is a unique vegetable grown in Japan. Mizuna has distinctive morphological characteristics such as forming a fairly large stump due to its high tillering ability, deeply lobed narrow leaves and small seeds that are not observed in other B. rapa vegetables. Including these two vegetables, B. rapa contains a wide range of variation in morphological and ecological characteristics (Takuno et al. 2007). The variations are comparable with those in B. oleracea.

It has been clarified that B. rapa was the maternal parent of B. juncea (2n = 36, AABB genome) in spontaneous hybridization with B. nigra. The clarification has been based on analyses of RuBisCo (Uchimiya and Wildman 1978), restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) in chloroplast DNA (Erickson et al. 1983) and mitochondrial genome sequences (Chang et al. 2011). B. juncea is similarly variable to B. rapa. It is a major oilseed crop in Southern Asia, while in East Asia, the species is cultivated as a leafy vegetable with various types of morphology. Because of the correspondence of morphological variations of B. rapa and B. juncea, it is of interest to investigate the differentiation of the cytoplasm within these two species. Such investigations are expected to provide detailed insight about the origins of cultivated B. rapa and B. juncea species.

Thus, in this article, we determined the complete sequences of the mitochondrial genome of Chinese cabbage and mizuna of B. rapa. We found a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) between the two sequences. Parallel intraspecific differentiation of mitochondria was observed in B. rapa and B. juncea using the SNP as a PCR-RFLP marker.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

A Chinese cabbage variety, ‘Oushou hakusai’, and a mizuna variety, ‘Chusei shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna’, were used for determination of their mitochondrial genome sequences. The plants were grown in a glasshouse, and the leaves of well-developed plants were used for the isolation of mitochondrial DNA. For SNP analysis, additional 62 varieties or lines of B. rapa and 16 varieties of B. juncea were used. Total DNA was isolated from young leaves of the seedlings of the varieties or lines using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and used as template for PCR of the SNP containing region. The plant materials were purchased or obtained from the Gene Bank of the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences (Tsukuba, Japan) or Tohoku University (Sendai, Japan).

Mitochondrial DNA extraction

Mitochondrial DNA was isolated from the leaves of ‘Oushou hakusai’ and ‘Chusei shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna’ according to the method of Bonen and Gray (1980) using a discontinuous density gradient (1.15, 1.30, and 1.45 M sucrose) with additional DNaseI-treating step. That is, in order to reduce contamination by nuclear DNA, mitochondria in suspension solution (0.44 M Sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 3 mM EDTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% BSA) were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 0.04 mg/ml DNaseI. After the incubation, the solution was washed twice by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 15 min) and suspended in modified suspension solution (EDTA concentration was 20 mM). DNaseI-treated mitochondria were collected from the interface between 1.30 and 1.45 M sucrose, and mitochondrial DNA was purified by CsCl-ethidium bromide centrifugation and precipitated with ethanol.

Sequencing and sequence assembly of Chinese cabbage

Pyrosequencing on the GS-FLX system (Roche, Branford, CT, USA) and de novo assembly were conducted at Hokkaido System Science (Sapporo, Japan) for Chinese cabbage. A total of 125,780 reads (average read length 389 bp) corresponding to 49 Mbp was obtained, and they were assembled into 108 contigs (N50 contig size 10,890 bp) using GS De Novo Assembler v2.6 software. Contigs were selected by average read depth (greater than 80), and then all contaminating sequences such as from the chloroplast genome were identified by BLAST search and removed. All linkages between contigs were confirmed by genomic PCR followed by sequencing. The sequences were assembled in Sequencher software ver. 4.9 (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA).

Sequence analysis of Chinese cabbage

We identified the genes for known mitochondrial proteins and rRNAs and repeated sequences by BLAST searches (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). A tRNA gene search was conducted with the tRNAscan-SE program (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/) (Lowe and Eddy 1997). All genes were compared with the published Brassica rapa mitochondrial genome (JF920285). A genome map was generated using CGviewer (Stothard and Wishart 2005).

Sequencing and sequence assembly of mizuna

The sequencing of the mitochondrial genome of mizuna was performed on the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The libraries for Illumina sequencing were prepared with a Nextera DNAv2 Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) and Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina) and the sequencing conditions of MiSeq XXX 300 cycles (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 578,522 reads corresponding to 133.5 Mb were obtained. The reads were mapped against the sequence of the Chinese cabbage mitochondrial genome using the Bowtie2 algorithm. The SNPs and indels between the two sequences were estimated by the GATK package and they were investigated by determining the DNA sequences from the direct sequencing of the PCR product in the variable regions.

SNP detection by PCR-RFLP

Because one SNP was ascertained between Chinese cabbage and mizuna, PCR-RFLP analysis was conducted. The DNA containing the SNP site was amplified by PCR with the following primers: forward = A.ABMT-SBS-F (5′-TTCTCTACAGCACTCTCGGAC-3′), reverse = A.ABMTSBS-R (5′-AAGAGAGAATCGTTGGTTCCT-3′). The amplified DNA was treated with the restriction enzyme EarI, which recognizes the DNA sequence of Chinese cabbage in the SNP site.

Results

Mitochondrial genome of Chinese cabbage and mizuna

Based on analysis with the next-generation sequencer, 108 contigs were obtained for Chinese cabbage. Of the 108 contigs, 31 were judged to compose the mitochondrial DNA of ‘Oushou hakusai’. The mitochondrial genome was assembled into a 219,763 bp circular molecule.

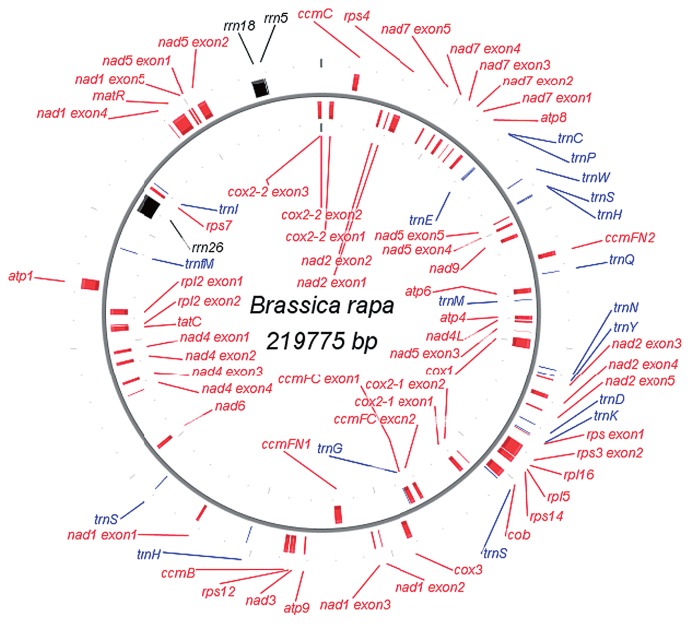

The reads of mizuna obtained by the MiSeq analysis were mapped to the aforementioned mitochondrial genome of Chinese cabbage. As a result, SNPs were observed in 13 sites and indels in 9. We therefore determined the DNA sequences of the variable sites between the two cultivars by sequencing the PCR products. The results of DNA sequencing demonstrated that the data on Chinese cabbage obtained by the GS-FLX system contained errors but that the data of mizuna were correct. Consequently, only one SNP was ascertained between the two cultivars. The mitochondrial genomes of Chinese cabbage and mizuna (AP017996, AP017997) are identical except for the SNP. The genome size of both mitochondria is 219,775 bp. The structure of the mitochondrial genome of Chinese cabbage is shown in Fig. 1. Its size was larger than that of B. rapa (JF 920285) reported by Chang et al. (2011) by 28 bp, a difference caused by indels in 30 nucleotides of the 29 mononucleotide repeat sites as described later. Other than the indels, the sequences coincided for Chinese cabbage and those obtained from the data of Chang et al. (2011). The mitochondrial genome of B. rapa contains 55 genes, including 34 protein-coding genes, 3 rRNA genes and 18 tRNA genes (Table 1). While B. rapa and B. oleracea have cox2-2, B. nigra lacks it, and trnH that is possessed in a single copy by B. nigra and B. oleracea is present in two copies in B. rapa (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Structure of mitochondrial genome of Chinese cabbage, ‘Oushou hakusai’, a cultivar of Brassica rapa.

Table 1.

Mitochondrial genome of Brassica rapa in comparison with Brassica nigra and Brassica oleacea

| B. rapa (This article) | B. nigra (Yamagishi et al. 2014) | B. oleracea (Tanaka et al. 2014) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 219,775 | 232,145 | 219,952 |

| Protein-coding genes | 34 | 33 | 34 |

| rRNA | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| tRNA | 18 | 17 | 17 |

| Total gene content | 55 | 53 | 54 |

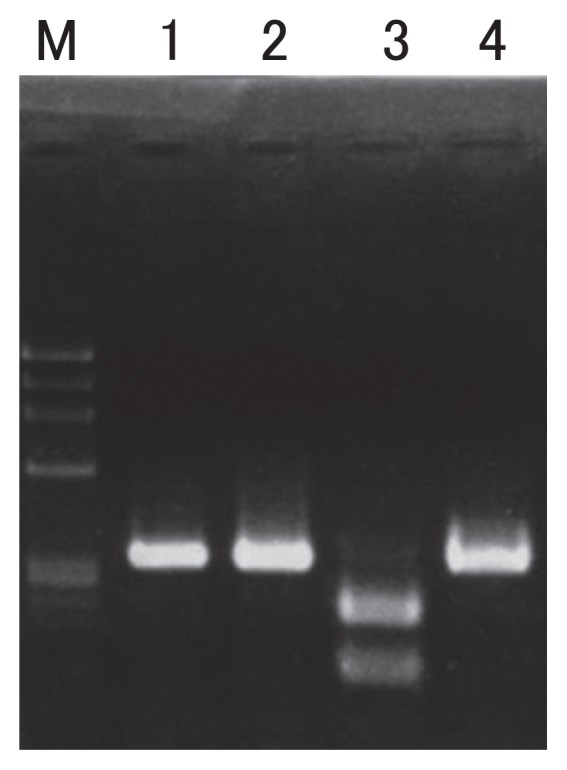

The SNP site is in the intergenic region between rps14 and cob. Chinese cabbage possesses nucleotide C at position no. 79579 according to Chang et al. (2011), while the nucleotide is A in mizuna. The SNP induces a RFLP when using the restriction enzyme EarI (Fig. 2). The cam mitotype reported by Chang et al. (2011) has C, as does Chinese cabbage.

Fig. 2.

RFLP induced by a SNP between the mitochondrial genomes of Chinese cabbage and mizuna. M: Molecular size marker (Φx174/Hae III); 1: PCR product of ‘Oushou hakusai’; 2: PCR product of ‘Chusei shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna’; 3: PCR product of ‘Oushou hakusai’ treated with Ear I; 4: PCR product of ‘Chusei shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna’ treated with Ear I.

Intraspecific differentiation of mitochondrial genomes in B. rapa and B. juncea

Based on the SNP found between Chinese cabbage and mizuna, we investigated intraspecific differentiation in B. rapa. Because B. juncea is an amphidiploid species whose cytoplasm is derived from B. rapa, we also included cultivars of B. juncea in the study. In B. rapa, most cultivars of various groups showed an RFLP pattern identical with Chinese cabbage (hereafter, Chinese cabbage type). The plants with the RFLP pattern of mizuna (hereafter, mizuna type) were concentrated mainly in six cultivars of mizuna, though ‘Sendai yukina’ (chinensis group), a local vegetable in the Tohoku area of Japan, and ‘C-639’, belonging to the group of oilseed rape ‘Sarson’, also were the mizuna type. In addition, the line ‘C-139’ stocked at Tohoku University contained both Chinese cabbage type and mizuna type individuals (Table 2). Although mibuna belongs to the same japonica group as mizuna, all the cultivars investigated in this study were the Chinese cabbage type.

Table 2.

Differentiation of mitotype in B. rapa

| Groupa | Mitotype | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Chinese cabbage type | Mizuna type | |

| chinensis | Seppaku taisai, Saishin, Chingensai, | Sendai yukina |

| Pakchoi | ||

| japonica | Maruba mibuna-T, Sousei kyomibuna, | Bansei sensuji kyomizuna, Bansei shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna |

| Maruba mibuna-A, Sousei mibuna, | Harihari mizuna, Kyomizuna, | |

| Maruba mibuna(M)-H, Maruba mibuna(C)-O | Shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna, Sousei sensuji kyomizuna | |

| Maruba mibuna(B)-O | ||

| narinosa | Chijimi yukina, Kisaragina, Taasai, | |

| Nagaokana, Yonezawa yukina | ||

| oleifera | Nanohana, Shiroguki hatakena, Hatakena, | |

| Mizukakena | ||

| pekinensis | Keuryu, Yamato mana, Shimokita mana, | |

| Kashin hakusai, Nozaki No.2, Hiroshimana, | ||

| Hikoshima haruna, Bansei mana, Ohsho, | ||

| Daibansei shirona kibakei | ||

| rapifera | Wakana, Zenkoji huyuna, Meike komatsuna, | |

| Kumamoto kyona, Nobuo huyuna, Kanamachi kokabu, | ||

| Hinona, Kireba tennoji kabu, Kaida kabu, Atsumi, | ||

| Yamakabu, Shogoin, Maruba tennoji kabu, Nozawana | ||

| Komatsuna, Yaseikabu, Inekokina | ||

| toria and sarson | C-504, C-506, C-635, C-663, C-665 | C-639 |

| unknown | C-120, C-121, C-123, C-147, C-139b | C-139b |

The group names in B. rapa are based on The Japanese Society for Horticultural Science (1979).

A variety with the underline shows the differentiation into two types within it.

In contrast to B. rapa, the majority of B. juncea was the mizuna type. Eleven out of 16 varieties observed were the mizuna type, whereas four varieties belonging to ‘Kobutakana’ (integrifolia group) and ‘Kikarashina’ (cernua group) had the Chinese cabbage type. ‘Hakarashina’ (cernua group) exhibited both two types within the variety (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differentiation of mitotype in B. juncea

| Groupa | Mitotype | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Chinese cabbage type | Mizuna type | |

| bulbifera | Zasai | |

| cernua | Kikarashina-S, | Hakarashina-Tb |

| Kikarashina-T | ||

| Hakarashina-Tb | ||

| integrifolia | Kobutakana, | Katsuona, Aka obatakana |

| Unzen kobutakana | ||

| rugosa | Bansei hiraguki obatakana | |

| Miike oba chirimentakana, | ||

| Yamagata seisai | ||

| Unzen kekkyutakana, | ||

| Kekkyutakana | ||

| Yanagawa oh chirimentakana | ||

| Miike akatakana | ||

| other | Serifon | |

The group names in B. juncea are based on The Japanese Society for Horticultural Science (1979).

A variety with the underline shows the differentiation into two types within it.

Discussion

This is the first report demonstrating intraspecific differentiation of the mitochondrial genome of B. rapa. As far as we know, no intraspecific differentiation has been reported to date for neither mitochondrial genome nor chloroplast genome of B. rapa. One SNP was found between the complete genome sequences for Chinese cabbage ‘Oushou hakusai’ and mizuna ‘Chusei shiroguki sensuji kyomizuna’, which had an identical genome size of 219,775 bp. It is remarkable that only one SNP was found between these two varieties of B. rapa, which show very distinct morphological characteristics. This is in contrast to radish (Raphanus sativus), which contains large structural variations in the mitochondrial genome within the species (Tanaka et al. 2012). For comparison, there are only three mitochondrial genome SNPs between two subspecies of Hordeum vulgare, wild and cultivated barley (ssp. spontaneum and ssp. vulgare), both having a genome size of 525,599 bp (Hisano et al. 2016).

The size of the mitochondrial genome we determined is larger than that (219,747 bp) reported by Chang et al. (2011) for B. rapa, who adopted the 454 sequencing technology, known to have a high error rate in detecting A or T homopolymers (Jeong et al. 2014, Margulies et al. 2005). Thus, we determined the sequences of the indel sites by direct sequencing of the PCR amplicons. From the variety name, ‘Suzhouqing’, used by Chang et al. (2011) for B. rapa, it was estimated as a cultivar of pak choi (chinensis group) (Zhang, personal communication). Therefore, we used ‘Pak choi’ (Takii Seed, Kyoto, Japan) for the determination of the sequences at the indel sites. Among the indels of the 30 nucleotides responsible for the difference of 28 bp between the two reports, 18 were in mononucleotide repeats of A and 10 were in repeats of T. The other two indel sites were observed to be homopolymers of G and C (Supplemental Table 1), so the majority of indels were in A or T homopolymers. Direct sequencing demonstrated that our sequences were correct for all 30 indels, while those from Chang et al. (2011) contained errors. Therefore, the mitochondrial genomes of 219,775 bp demonstrated in this article for the two cultivars accurately represent those of B. rapa.

Intraspecific variation in the mitochondrial genome has also been observed in the other two diploid Brassica species, B. oleracea and B. nigra. In B. oleracea, the mitotype ole reported by Chang et al. (2011) is 360,271 bp while cabbage and cauliflower are 219,952 bp (Tanaka et al. 2014) and 219,962 bp (Grewe et al. 2014), respectively. We inferred that the intraspecific variation between the genomes reported by Chang et al. (2011) and Tanaka et al. (2014) is due to heteroplasmy and substoichiometric shifting (Tanaka et al. 2014). On the other hand, intraspecific variation due to indels was found in B. nigra (Yamagishi et al. 2014). The mitochondrial genome of B. nigra that we determined was 232,145 bp, but a line of B. nigra had an insertion of 33 bp in the rps3 gene. Recently, Yang et al. (2016) reported a genome size of 232,407 bp in B. nigra, 262 bp larger than what we determined. The reason for the difference in size between our variety and that of Yang et al. (2016) requires further study. It is interesting that the intraspecific differentiations of the mitochondrial genomes of the three diploid Brassica crops are caused by unique mechanisms in each species; namely, a SNP in B. rapa, an indel in B. nigra and substoichiometric shifting in B. oleracea.

The two mitotypes distinguishable by the SNP showed contrasting distribution in B. rapa and B. juncea. In B. rapa, the mitochondrial genome of most varieties is the Chinese cabbage type, with the mizuna type restricted to varieties of the japonica group and a few other cultivars. In addition, a Japanese local variety, ‘Sendai yukina’, is the mizuna type, though it is included in the chinensis group, the fact providing a clue to the origin of this variety. On the other hand, one line of the sarson group (C-639) grown in Southern Asia as an oil crop is the mizuna type. To determine the phylogenetic relationship between mizuna and sarson, genome sequencing of sarson would be necessary.

It is noteworthy to also mention that all the cultivars of mibuna have mitochondria of the Chinese cabbage type (Table 2). Mizuna and mibuna both belong to the japonica group and except for the leaf shape, have many common features. The only difference is that the leaves of mizuna are deeply indented while mibuna has entire leaves. The difference of the mitotype suggests that mibuna is derived from hybridization between mizuna and another vegetable having the Chinese cabbage type mitochondria. It is further inferred that mizuna had contributed as a pollen parent in that hybridization.

In contrast to B. rapa, mizuna type mitochondria is predominant in B. juncea (Table 3). The mizuna type distributes not only in leaf mustard (cernua group), but also in integrifolia group, rugosa group and bulbifera group. Comparative studies on whole mitochondrial genome sequences of mizuna type in B. juncea with that of mizuna demonstrated here would clarify the genetic relationship between the mizuna type mitochondria of B. rapa and that of B. juncea in detail.

The two mitochondrial types based on the SNP are distributed in both B. rapa and B. juncea, although the frequencies of the types differ between the two species (Tables 2, 3). It is well-known that B. juncea (AABB) is a spontaneous amphidiploid produced by the interspecific hybridization between wild diploid plants of B. rapa (AA) and B. nigra (BB) (U 1935); B. rapa contributed as a female parent in the hybridization, as described previously. Using the SNP between the two mitotypes, we checked several B. nigra lines for the SNP region. B. nigra showed the Chinese cabbage type (Data not shown), and thus, we could not distinguish between the majority of B. rapa and B. nigra with this SNP. However, by the precise determination of the mitochondrial genome of B. rapa, we found that the mitochondrial genomes of B. rapa and B. nigra differ in size (more that 12,000 bp difference) as shown in Table 1. Comparison of the different sites between the two species with B. juncea would provide further evidence for the maternity of B. rapa.

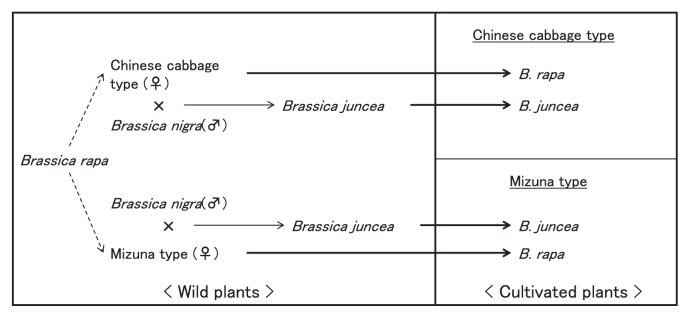

The intraspecific differentiation of mitochondrial genomes in B. rapa and B. juncea suggest the origins of the cultivated plants in B. rapa and B. juncea as shown in Fig. 3. In wild plants of B. rapa, differentiation of the mitochondrial type into the Chinese cabbage type and mizuna type took place by a mutation. Plants of both types were domesticated independently and established as crops of B. rapa. Then, natural interspecific hybrids were produced independently between wild plants of B. rapa having each of the mitochondrial types and wild B. nigra as pollen parents. Chromosome duplication in the hybrids provided the new amphidiploid species, B. juncea. Thereafter, B. juncea lines of both mitochondrial types were domesticated. This scenario means that the domestication of B. rapa and production of B. juncea occurred at least twice, respectively. The progress of mitochondrial genome sequencing and analysis of intraspecific variation should enable clarification of the triangle of U on the evolution of Brassica in much more detail.

Fig. 3.

Schematic model for differentiation of mitochondrial genomes and domestication processes of B. rapa and B. juncea. ⇢; Differentiation of mitochondrial genome, →; Establishment of B. juncea,

; Domestication of B. rapa and B. juncea.

; Domestication of B. rapa and B. juncea.

Supplementary Information

Literature Cited

- Bonen, L. and Gray, M.W. (1980) Organization and expression of the mitochondrial genome of plants. I. The genes for wheat mitochondrial ribosomal and transfer RNA: evidence for an unusual arrangement. Nucleic Acids Res. 8: 319–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.X., Yang, T.T., Du, T.Q., Huang, Y.J., Chen, J.M., Yan, J.Y., He, J.B. and Guan, R.Z. (2011) Mitochondrial genome sequencing helps show the evolutionary mechanism of mitochondrial genome formation in Brassica. BMC Genomics 12: 497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darracq, A., Varré, J.S., Maréchal-Drouard, L., Courseaux, A., Castric, V., Saumitou-Laprade, P., Oztas, S., Lenoble, P., Vacherie, B., Barbe, V.et al. (2011) Structural and content diversity of mitochondrial genome in beet: a comparative genomic analysis. Genome Biol. Evol. 3: 723–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, L.R., Straus, N.A. and Beversdorf, W.D. (1983) Restriction patterns reveal origins of chloroplast genomes in Brassica amphiploids. Theor. Appl. Genet. 65: 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, S., Kazama, T., Yamada, M. and Toriyama, K. (2010) Discovery of global genomic re-organization based on comparison of two newly sequenced rice mitochondrial genomes with cytoplasmic male sterility-related genes. BMC Genomics 11: 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewe, F., Edger, P.P., Keren, I., Sultan, L., Pires, J.C., Ostersetzer-Biran, O. and Mower, J.P. (2014) Comparative analysis of 11 Brassicales mitochondrial genomes and the mitochondrial transcriptome of Brassica oleracea. Mitochondrion 19: 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano, H., Tsujimura, M., Yoshida, H., Terachi, T. and Sato, K. (2016) Mitochondrial genome sequences from wild and cultivated barley (Hordeum vulgare). BMC Genomics 17: 824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y-M., Chung, W-H., Mun, J-H., Kim, N. and Yu, H-J. (2014) De novo assembly and characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Gene 551: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, T. and Newton, K.J. (2008) Angiosperm mitochondrial genomes and mutations. Mitochondrion 8: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, T.M. and Eddy, S.R. (1997) tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies, M., Egholm, M., Altman, W.E., Attiya, S., Bader, J.S., Bemben, L.A., Berka, J., Braverman, M.S., Chen, Y-J., Chen, Z.et al. (2005) Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437: 376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, S. and Hinata, K. (1980) Taxonomy, cytogenetics and origin of crop Brassica, a review. Opera Bot. 55: 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stothard, P. and Wishart, D.S. (2005) Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics 21: 537–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuno, S., Kawahara, T. and Ohnishi, O. (2007) Phylogenetic relationships among cultivated types of Brassica rapa L. em. Metzg. as revealed by AFLP analysis. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 54: 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y., Tsuda, M., Yasumoto, K., Yamagishi, H. and Terachi, T. (2012) A complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Ogura-type male-sterile cytoplasm and its comparative analysis with that of normal cytoplasm in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). BMC Genomics 13: 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y., Tsuda, M., Yasumoto, K., Terachi, T. and Yamagishi, H. (2014) The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Brassica oleracea and analysis of coexisting mitotypes. Curr. Genet. 60: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Japanese Society for Horticultural Science (ed.) (1979) Engeisakumotsu meihen. Yokendo, Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- U, N. (1935) Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Japn. J. Bot. 7: 389–452. [Google Scholar]

- Uchimiya, H. and Wildman, S.G. (1978) Evolution of fraction I protein in relation to origin of amphidiploid Brassica species and other members of the Cruciferae. J. Hered. 69: 299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi, H., Tanaka, Y. and Terachi, T. (2014) Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of black mustard (Brassica nigra; BB) and comparison with Brassica oleracea (CC) and Brassica carinata (BBCC). Genome 57: 577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., Liu, G., Zhao, N., Chen, S., Liu, D., Ma, W., Hu, Z. and Zhang, M. (2016) Comparative mitochondrial genome analysis reveals the evolutionary rearrangement mechanism in Brassica. Plant Biol. 18: 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.