OVERVIEW

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort associated with a change in bowel patterns, is one of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders. Because no single drug effectively relieves all IBS symptoms, management relies on dietary and lifestyle modifications, as well as pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies. The authors review current approaches to treatment and discuss nursing implications.

Keywords: constipation, diarrhea, gastrointestinal, irritable bowel syndrome, symptom management

Melinda Cooley is a 31-year-old white woman who works as a paralegal. (This case is a composite based on our experience.) After quickly finishing lunch at her office desk, she hurries to her car so she won’t be late picking up her two sons from baseball practice. Suddenly, she feels sharp, cramping abdominal pains and the urgent need to defecate. Although she’s running late, she returns to her office to use the restroom. Ms. Cooley fears she’ll soil herself if she doesn’t completely empty her bowels now. Having a bowel movement reduces her pain slightly, and she is able to drive. After dinner, however, she feels bloated and her abdominal pain returns.

A few weeks later, during a routine appointment with her NP, Ms. Cooley relates that she is “usually constipated.” She says she has tried taking fiber supplements, but none has helped and her abdominal pain has worsened lately. Seeing from the patient chart that Ms. Cooley has mentioned episodic abdominal pain, fatigue, and constipation on previous visits, the NP records her symptom history and current medications (multivitamins, oral contraceptives, and ibuprofen). On physical examination, he notes mild tenderness while palpating Ms. Cooley’s left lower abdominal quadrant but feels no mass. He orders a complete blood count and refers Ms. Cooley to a gastroenterologist.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and associated with such alterations in bowel patterns as diarrhea, constipation, or both. Other supportive signs and symptoms may include hard, lumpy, loose, or watery stools; bloating; passing mucus; straining to defecate; bowel urgency; and the feeling of incomplete bowel evacuation. The prevalence of IBS is estimated to be between 5% and 10% in North America, where the condition is nearly 50% more common among women than men, and between 7% and 10% worldwide.1 IBS occurs in all age groups but is more commonly diagnosed in patients under the age of 50.1 There are limited data on racial and ethnic differences among those with IBS, but the condition is more common in lower socioeconomic groups.2

According to the Rome III Diagnostic Criteria for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, a system developed by an international panel of gastrointestinal (GI) experts, IBS can be diagnosed six months after symptom onset in patients who, on at least three days per month for the past three months, have experienced recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort and at least two of the following3:

pain improvement with defecation

change in stool frequency at onset

change in stool form or appearance at onset

Rome III criteria classify IBS into four subtypes characterized by predominant associated stool patterns: IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS mixed (IBS-M), and IBS unsubtyped (IBS-U).3 (See Table 13). A recent systematic review suggests that subtype prevalence may vary between the sexes, with IBS-C more common in women, IBS-D more common in men, and IBS-M equally common in both.4

Table 1.

Subtyping IBS3

| IBS with constipation (IBS-C) | At least 25% of stools are hard or lumpy and less than 25% are loose (mushy) or watery |

| IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) | At least 25% of stools are loose (mushy) or watery and less than 25% are hard or lumpy |

| IBS mixed (IBS-M) | At least 25% of stools are hard or lumpy and at least 25% are loose (mushy) or watery |

| IBS unsubtyped (IBS-U) | Insufficient abnormality of stool consistency to meet criteria for IBS-C, IBS-D, or IBS-M |

IBS = irritable bowel syndrome.

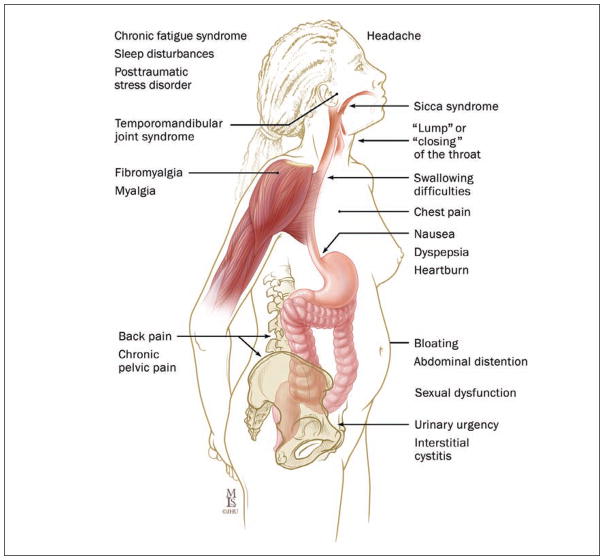

In addition to GI problems, patients frequently report such symptoms as headache, fatigue, depression, and anxiety.5 IBS symptoms frequently have a tremendous impact on work, social activities, quality of life, and health care resource utilization.6–9 Patients with IBS consistently report increased absences from school and work, limitations in social activities, and the need to make lifestyle modifications.10, 11 In year 2000 dollars, annual direct and indirect costs of IBS have been estimated as nearly $22 billion.12

In this article, we review IBS presentation, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and current pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to treatment. Through the composite case history of Ms. Cooley and a discussion of available evidence, we outline the role of RNs, primary care providers, and gastroenterologists in helping patients manage this life-altering condition.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

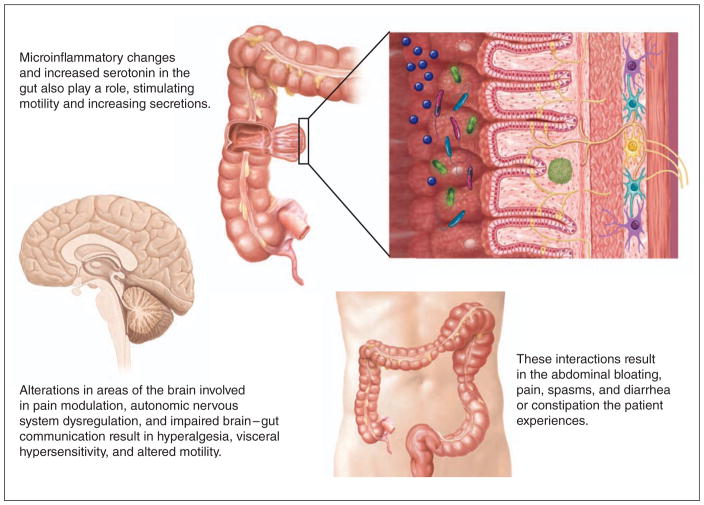

A number of factors are presumed to play a role in the etiology of IBS, including altered gut motility, enhanced visceral sensitivity, and abnormal serotonin levels in the GI tract.13 It’s been proposed that the altered intestinal immune activation observed in people with IBS may result from increased mucosal permeability and the subsequent release of inflammatory mediators.14

Alteration in gut microflora and bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine may be involved in IBS pathogenesis, although there is little data on the mechanisms by which this occurs.15 Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and fermentation have been investigated as possible causes of such symptoms as bloating, although the evidence is mixed.16 In addition, a subset of IBS, known as postinfectious IBS, which is associated with mucosal immune alteration and inflammation, may develop in people after infective gastroenteritis.15, 17 There is also evidence to suggest an increased prevalence of celiac sprue in patients with IBS. A systematic review concluded that celiac disease was four times as prevalent in individuals meeting the diagnostic criteria for IBS as in control subjects.18

Epidemiologic studies show that IBS aggregates in families, suggesting a genetic component to the disorder.19, 20 Moreover, people with IBS frequently report a family history of IBS, and their relatives are two to three times more likely to have IBS than the relatives of those without IBS.21 It remains unclear, however, which genes or shared environmental factors may be involved.19, 20

Psychological conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are often observed in patients with IBS.22–26 Some studies suggest that this is because psychosocial and environmental stress play a role in IBS pathogenesis24 or exacerbate symptoms.27, 28

DIAGNOSIS

There are no known biomarkers for IBS, so diagnosis is based on the patient’s self-reported symptoms, a complete medical history, and a physical examination. The history taking should focus on the site, nature, and duration of the abdominal pain; the associated change in stool form or bowel habits; any instance of bloating or passing mucus; and any association with menses. A visual aid, such as the Bristol Stool Form Scale (http://1.usa.gov/ZwCr0T), may be useful in gathering specific information about stool changes.

When assessing a patient for IBS, carefully record all medications. Numerous over-the-counter and prescribed medications can cause abdominal symptoms such as pain and changes in bowel habits. In addition, the symptoms of IBS overlap with or are similar to those of many other conditions, including functional dyspepsia, celiac disease, lactose intolerance, and functional constipation (see Table 229–35).

Table 2.

| Gastrointestinal | Drug Toxicity |

| Crohn’s disease | Antibiotics |

| Ulcerative colitis | Chemotherapy agents |

| Microscopic colitis | Proton pump inhibitors |

| Colorectal cancer | ACE inhibitors |

| Celiac disease | NSAIDs |

| Functional constipation/diarrhea | β-blockers |

| Functional dyspepsia | |

| Endocrine/Metabolic | |

| Infectious | Thyroid disorder |

| Parasitic | Diabetes mellitus |

| Viral gastroenteritis | Hypercalcemia |

| HIV-associated infections | Pancreatic endocrine tumors |

| Giardiasis | |

| Dietary | |

| Neurologic | Lactose intolerance |

| Parkinson’s disease | Fructose intolerance |

| Multiple sclerosis | Caffeine |

| Spinal cord pathology | Alcohol |

| Food allergy | |

| Gynecologic | |

| Endometriosis | |

| Ovarian cancer |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; IBS = irritable bowel syndrome; NSAID = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

Abdominal examination can help rule out such pathologies as abdominal masses, intestinal obstruction, or an enlarged liver or spleen. Patients with IBS often experience tenderness of the lower left abdominal quadrant upon palpation, although this finding is “neither specific nor sensitive enough” to be used as the basis for diagnosis.36 A digital rectal exam may be performed to exclude palpable rectal cancer or abnormal function of the anorectal sphincter.

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome recommends routine serologic screening for celiac disease in patients with IBS-D and IBS-M, as well as colonic imaging to rule out organic disease in patients with IBS symptoms who are over age 50 or who have any of the following “alarm” features1:

rectal bleeding

unexplained weight loss

iron deficiency anemia

nocturnal symptoms

family history of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), or celiac disease

Other indications of serious underlying conditions that require further evaluation include31, 32:

new onset after age 50

new or progressive symptoms

recent antibiotic use

travel history to areas where parasitic disease is endemic

fever

frank or occult blood in the stool

abdominal mass

enlarged lymph nodes

signs of bowel obstruction, thyroid dysfunction, or malabsorption

active arthritis

dermatitis

persistent diarrhea

severe constipation

In clinical practice, laboratory studies commonly ordered for patients with suspected IBS include tests for stool ova, intestinal parasites, and fecal occult blood; complete blood count; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; serum chemistries; thyroid function studies; and lactulose and glucose breath testing. In the absence of alarm features, however, current data indicate that such testing identifies few patients meeting the Rome III criteria.37, 38

Examining Ms. Cooley

When the gastroenterologist reviews Ms. Cooley’s history and blood work, she notes that Ms. Cooley’s family history is negative for IBD and colon cancer, and her thyroid-stimulating hormone level is within the normal range. Ms. Cooley says that, since college, she’s had what she terms a “sensitive stomach.” She frequently feels bloated and crampy after eating, and she has difficulty passing her stools, which tend to be small and pebble shaped, although she has about one normal bowel movement per week. Her abdominal pain occurs after every meal and can last anywhere from one to two hours. She thinks the pain and constipation worsen right before her menses. She explains that the pain has caused her to miss several of her sons’ activities and so many days of work that she fears losing her job.

Based on Ms. Cooley’s history, physical examination, absence of alarm features, and constipation-predominant stool pattern, the gastroenterologist diagnoses IBS-C. She tells Ms. Cooley to return in one month, prescribes the stool softener docusate (Colace and others), and advises Ms. Cooley to keep a food and stool diary, while making certain lifestyle and dietary modifications, which the RN explains in detail.

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT: MODIFYING LIFESTYLE AND DIET

Since there is no known cure for IBS, current treatment focuses on managing symptoms through lifestyle and dietary modifications, as well as pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies. Lifestyle modifications such as regular exercise and stress reduction are often helpful in reducing IBS symptoms.39 A survey of 666 patients with IBS showed that dietary modification, patient education, and exercise were the interventions most frequently utilized, and patients expected greater benefit from these than from drugs.40 Physical activity has been shown to enhance intestinal gas clearance and reduce abdominal bloating and constipation.41–43 Regular exercise may also reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression.44, 45 Nurses can direct patients to exercise programs that meet their individual needs.

Likewise, nurses can help patients identify life stressors that may exacerbate symptoms and can suggest ways to incorporate physical activity and other stress reduction techniques (such as deep breathing, relaxation, guided imagery, counseling, yoga, and meditation) into their lives. Nurses can teach patients that stress is believed to play an important role in IBS development and exacerbation,27 while providing reassurance that simple relaxation exercises may help them to control the frequency or severity of their symptoms.

Patients commonly report symptom exacerbation with such foods as dairy products, cereals, caffeine-containing foods, coffee with or without caffeine, alcohol, and the artificial sweeteners sorbitol and xylitol.46 It’s also been suggested that fermentable poorly absorbed carbohydrates or fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), which include wheat, rye, fruits, legumes, onions, garlic, and honey, in addition to milk and sweeteners, can trigger symptoms.46 One study found that a low FODMAP diet improved symptoms in three IBS subtypes—IBS-C, IBS-D, and IBS-M—and that reintroducing dietary fructose or fructans exacerbated symptoms.47 There is also evidence that some patients with IBS for whom celiac disease has been excluded may benefit, nonetheless, from a gluten-free diet.48 Although some clinicians suggest increasing dietary fiber, this practice may have mixed results. While dietary fiber may reduce GI transit time and add bulk to the stool, thereby relieving constipation in some patients with IBS-C, it may also lead to abdominal distension, bloating, and flatulence, thus limiting its positive effect.

Clinicians often advise their patients to keep a daily food and stool diary—noting the time, content, and amount of every meal and snack; symptoms, with severity rated on a scale of 1 (for mildest) to 10 (for most severe); the frequency and consistency of every stool, as well as any associated pain, straining, urgency, or incomplete evacuation; and potential contributing factors (such as mood or stress)—so patients can identify foods to exclude from their diet as well as nondietary triggers. Nurses can work with or refer patients to a dietitian, who can offer individual guidance on dietary modifications.

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENTS FOR IBS SYMPTOMS

Because of the diversity of symptoms and stool patterns that present in IBS, pharmacologic treatment varies widely. Generally, treatment is determined by the predominant bowel pattern and the symptoms that most disrupt the patient’s quality of life (Table 31, 49–72).

Table 3.

| Predominant Symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Constipation | Stool softeners |

| Bulking agents | |

| Psyllium (Metamucil and others) | |

| Methylcellulose (Citrucel) | |

| Polycarbophil (FiberCon) | |

| Laxatives | |

| Osmotic | |

| Stimulant | |

| Lubiprostone (IBS-C) (Amitiza) | |

|

| |

| Diarrhea | Antidiarrheal agents |

| Loperamide (Imodium A-D) | |

| Diphenoxylate–atropine (Lomotil) | |

| Alosetron (IBS-D) (Lotronex) | |

|

| |

| Abdominal Pain and Discomfort | Antispasmodics |

| Dicyclomine (Bentyl) | |

| Hyoscyamine (Levsin and others) | |

| Peppermint oil | |

| TCAsa | |

| Amitriptyline | |

| Desipramine (Norpramin) | |

| Doxepin (Silenor and others) | |

| SSRIsa | |

| Fluoxetine (Prozac and others) | |

| Paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva) | |

| Citalopram (Celexa) | |

IBS = irritable bowel syndrome; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant.

Use for this purpose is off label.

Constipation

A number of over-the-counter and prescription medications may be used to manage symptoms in patients with constipation.

Stool softeners, such as docusate, are surface-acting agents that moisten the stool.73 These agents may be recommended for short-term use in patients who strain during defecation.

Bulking agents, such as psyllium (Metamucil and others), methylcellulose (Citrucel), polycarbophil (Fibercon), and bran, which absorb water and often induce peristalsis in patients with constipation, are sometimes recommended for the treatment of IBS-C. Like high-fiber foods, these agents may provide benefit in some patients, but the results are mixed.65 The ACG Task Force concluded that neither wheat bran nor corn bran is more effective than placebo, but psyllium husk is moderately effective in improving global IBS symptoms.1 A recent Cochrane review, however, found no evidence that bulking agents benefit patients with IBS.74 As with patients who increase their dietary fiber to alleviate constipation in IBS-C, those who use bulking agents should be advised that their use may cause bloating, abdominal distension, and flatulence.1

Osmotic laxatives, which draw water into the bowels, softening stool consistency and increasing stool frequency, are often used by patients with constipation and delayed intestinal transit. Laxatives have not been well studied in IBS, but one small study of adolescents with IBS demonstrated that polyethylene glycol (PEG) improved stool frequency, although it had no effect on pain intensity.57 Osmotic laxatives, such as PEG, may cause abdominal bloating, nausea, cramping, and gas.73

Lubiprostone (Amitiza), a selective type 2 chloride channel activator approved to treat IBS-C in women ages 18 and older, works by activating chloride channels in the intestine and promoting fluid secretion to allow the stool to pass more easily.69 An analysis of two phase 3 clinical trials, involving 1,171 patients with IBS-C, found that lubiprostone 8 mcg, administered orally twice a day for 12 to 16 weeks, produced a significantly greater percentage of “overall responders” (defined as patients who were responsive to treatment for at least two of the three months of the study) than placebo and significantly improved quality of life in the areas of body image and health worry.53 Adverse effects may include nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, but lubiprostone has been found to be safe and well tolerated over nine to 13 months of treatment.75

Tegaserod (Zelnorm) is a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) type 4 receptor partial agonist that is no longer available in the United States except through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use in life-threatening situations.70 The drug was initially approved by the FDA in 2002 for the treatment of IBS-C in women.76 In clinical trials, it was shown to be superior to placebo in improving global IBS symptoms,55 but it was withdrawn from the market in 2007 because of an increased risk of cardiovascular events.70

Diarrhea

Patients whose IBS is characterized by diarrhea have faster GI transit times than healthy people and may benefit from agents that delay GI transit.

Antidiarrheal agents, such as loperamide (Imodium A–D) and diphenoxylate in combination with atropine (Lomotil), slow GI transit time by inhibiting intestinal peristalsis, although loperamide is the only such agent that has been evaluated in randomized controlled trials for the specific purpose of treating IBS-D.1 According to the ACG Task Force, loperamide is “not more effective than placebo” in reducing IBS pain or global symptoms, but it may reduce stool frequency and improve stool consistency.1 Adverse effects may include abdominal pain, distension, or discomfort.77

Alosetron (Lotronex) is a selective serotonin antagonist that acts at the 5-HT type 3 (5-HT3) receptor. In February 2000, alosetron was approved to treat IBS-D in women, but it was withdrawn from the market in November 2000 following reports of adverse events such as ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation.1 In 2002, it was reintroduced and made available by prescription only to patients of physicians enrolled in a restricted marketing program for the treatment of women with severe IBS-D that has not responded to other treatment. Since September 2010, NPs and physician assistants enrolled in the FDA-mandated prescription program are also able to prescribe alosetron to women with severe IBS-D.78

Alosetron works by blocking the action of serotonin in the GI tract,64 where 95% of the body’s serotonin is found.1 In the gut, serotonergic transmission and signaling to the central nervous system is mediated by 5-HT31; by antagonizing 5-HT3, alosetron slows the movement of stool through the intestines and reduces visceral sensation.64 Studies have shown its efficacy over placebo in improving global IBS symptoms, including abdominal pain and discomfort, stool consistency, urgency, and stool frequency.50, 51, 58, 60, 72

Abdominal pain and discomfort

The antispasmodic agents hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) and dicyclomine (Bentyl) were found to be effective in providing short-term relief of abdominal pain and discomfort in clinical trials for IBS.1 Both are anti-cholinergic agents, which inhibit the action of acetylcholine at the muscarinic receptors of the gut, thereby relaxing smooth muscle in the stomach and intestine. In addition, they reduce stomach acid secretion. It should be noted that hyoscine butylbromide, which the ACG Task Force considers to have “the best evidence for efficacy,” is not currently available in the United States, although hyoscyamine (Levsin and others), which is closely related but not identical to hyoscine butylbromide, is.1 For both hyoscyamine and dicyclomine, adverse effects may include constipation, dry mouth, nausea, dizziness, drowsiness, blurry vision, and urinary retention.77 Long-term efficacy and safety data for the use of antispasmodics in IBS are not available.74

Rifaximin (Xifaxan)

As alterations in gut micro-flora have been suggested as factors in the pathophysiology of IBS, recent evidence indicates that the nonsystemic antibiotic rifaximin may be a potential treatment for bloating and may relieve global symptoms in nonconstipated patients with IBS.62, 63, 67 Rifaximin is currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea and is under FDA review for use in IBS. The most common adverse events associated with rifaximin are headache, upper respiratory infection, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea.62 Long-term safety, efficacy over repeated treatment courses, and the potential for antibiotic resistance require further investigation.

Antidepressants can be used off label to treat moderate-to-severe IBS in patients for whom other treatments have failed to provide relief.79 Both tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been used to treat abdominal pain in IBS, with benefits likely stemming from regulation of both central and peripheral nervous system mechanisms.1

TCAs inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and nor-epinephrine. Studies indicate that TCAs, including desipramine (Norpramin), doxepin (Silenor and others), and amitriptyline, are more effective than placebo in reducing abdominal pain and relieving global IBS symptoms.49, 54, 56, 80 TCAs also prolong gut transit times, which may be useful in treating patients with diarrhea.52 The dosages used to treat IBS (10 to 150 mg daily) are generally lower than those used to treat mood disorders.56 Nevertheless, possible adverse effects of TCAs, including constipation, sedation, dry mouth, and urinary retention, may limit their therapeutic use in this context.79

The efficacy data for SSRIs, which include fluoxetine (Prozac and others), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva), and citalopram (Celexa), are more limited and mixed in demonstrating benefit in IBS.59, 61, 71 Since SSRIs tend to stimulate gut motility, they may be more useful in patients with IBS-C.66, 68, 71 The adverse effects of SSRIs include diarrhea, nausea, and cramping.81 Global symptoms of IBS are more likely to improve with the use of antidepressants, although there are limited data on their safety and tolerability within this treatment context.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPIES

When Ms. Cooley returns to the gastroenterologist for her follow-up appointment, she reports that her symptoms have improved over the past month. She brings her food diary and reviews it with the RN, looking for any food patterns or situations that may be symptom triggers.

Ms. Cooley had some bloating and cramping after eating pizza, broccoli, and dairy products, but not yogurt. She explains that she often eats whatever her children eat and realizes that these choices are not always the healthiest. The RN gives her a referral to a dietitian who can further help her with meal planning. Ms. Cooley’s diary also reveals that her symptoms seem to be worse when she is at work. Ms. Cooley acknowledges that she feels stressed because she recently learned that her company is merging with a larger firm and she is afraid of losing her job. She frequently worries if she’s unable to empty her bowels before leaving the house or office, or if she’s unsure that a bathroom is close by. The RN reassures her that her condition is treatable and emphasizes the need to manage life stressors through exercise, relaxation techniques, proper sleep, and the support of family and friends. She suggests that Ms. Cooley join a patient support group or the weekly group stress management classes offered at the clinic.

Psychological therapies, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psychotherapy, and hypnotherapy, are often used in combination with other therapies to manage IBS and have been found to be beneficial in reducing global symptoms.1, 82

CBT aims to modify the cognitive aspect of the emotional or psychological states and linked physiologic responses that may trigger or exacerbate symptoms. For example, in Ms. Cooley’s case, stress at work seems to aggravate her symptoms; if CBT can help her recognize the thoughts, events, or behaviors that trigger symptoms and respond differently, it may help her alleviate her symptoms.83 In a Toronto study of 431 adults with moderate-to-severe functional bowel disorder, CBT was found to be significantly more effective in decreasing GI symptoms than an educational component, which included modified attention control sessions and general information on functional bowel disorders, provided in the absence of CBT by the same therapist.54

Typically, CBT is administered weekly in a group or individual format by a trained therapist. The number of sessions and the specific CBT strategies used (cognitive distortion, alternative thoughts, or social skills training, for example) may vary based on individual assessment. In one study, a significant proportion of patients with IBS had a positive response to CBT within four weeks of treatment.84 Another study demonstrated that a comprehensive self-management program combining education, diet, relaxation, and cognitive-behavioral strategies and delivered by psychiatric NPs, primarily by telephone, was effective in reducing GI symptoms (particularly abdominal pain or discomfort and intestinal gas) and improving quality of life.85

Gut-directed hypnotherapy is a form of hypnosis that employs such techniques as progressive relaxation and imagery, targeted at the gut, to reduce symptoms. Efficacy data are limited, but studies have found that gut-directed hypnotherapy may be effective in managing IBS, with 10 of 18 trials and five of six controlled trials showing a statistically significant improvement in GI symptoms, emotional symptoms, and quality of life.86, 87

Similar to CBT, gut-directed hypnotherapy is time intensive, usually requiring six to 12 sessions over a period of several months, and efficacy depends in part on patient motivation.86 Nurse-led gut-directed hypnotherapy shows promise as an effective88 and cost-effective89 treatment for IBS, although further studies are needed to determine the best form of delivery (group versus individual hypnotherapy versus hypnotherapy delivered by audiovisual means).

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

Because conventional therapeutic options for IBS are limited, many patients turn to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities. A small 2000 Florida study found that 32 of 73 subjects (43%) with GI disorders had used CAM therapies, and many considered them beneficial.90 In a population-based study, 21% of patients with IBS or functional dyspepsia had seen an alternative health care provider at least once for GI problems.91 CAM modalities for treating IBS may include probiotics, peppermint oil, acupuncture, and mind–body practices.

Probiotics are live microbiologic organisms present in foods such as yogurt with live, active cultures and fermented foods like kefir and sauerkraut. Probiotics are also available in dietary supplements. It’s been suggested that certain probiotics can improve digestive and intestinal functioning, and possibly immunomodulatory responses, by restoring the proper balance of gut microflora, although the exact mechanism is not well understood. Clinical studies examining the use of probiotics versus placebo are viewed with caution because of varying probiotic species, preparations, and doses.92 But two clinical trials found that the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 provides significantly more relief from abdominal pain, bloating, and bowel movement difficulty than placebo.93, 94

Peppermint oil, which blocks calcium channels in the gut, may improve global IBS symptoms, possibly by exerting an antispasmodic effect on the intestinal smooth muscle. The use of enteric-coated peppermint oil capsules has been found to be superior to placebo in reducing abdominal symptoms related to IBS.95–97 Clinical studies have tested doses ranging from 180 to 225 mg per capsule, taken before or with meals. Taken orally, peppermint oil can cause heartburn, which may be reduced with the use of enteric-coated capsules.98

Acupuncture has been used to treat GI symptoms of pain, nausea, and vomiting.99, 100 Its beneficial effects may result from the stimulation of the hypothalamus–pituitary system and the release of endorphins and en-kephalins.101 Other mechanisms by which acupuncture may induce an analgesic effect include activation of descending pain inhibitory pathways, deactivation of the limbic system, and release of adenosine with its antinociceptive properties.102, 103 Several clinical studies have evaluated acupuncture for IBS symptoms.104–107 A meta-analysis found that acupuncture results were variable and inconclusive because of the poor quality of the studies and that further research is necessary.108

Mind–body practices such as meditation have been used to treat a variety of disorders, including chronic pain and anxiety. A form of meditation frequently taught in health care settings is mindfulness meditation, which encourages awareness of the present moment and nonjudgmental attention to thoughts. Recent studies demonstrated that eight weeks of training in mindfulness meditation can substantially reduce IBS symptom severity, producing benefits that persist for at least three months after group training ends.109, 110 Since some patients with IBS appear to be hypersensitive to and hypervigilant about bodily sensations,111, 112 such mind–body interventions as meditation and yoga may help patients manage symptoms.

CONTINUED PATIENT CARE

After evaluating the severity of IBS symptoms and discussing a customized treatment plan with the patient, nurses must continue to provide support and education, thereby promoting treatment adherence. Data suggest that IBS patients often feel misunderstood or dismissed by their health care providers, reflecting the need for improved patient–provider communication.113 A recent qualitative study revealed that a major concern of patients with IBS is related to being heard and receiving empathy.114 By assessing the patient’s expectations, understanding, and motivation at the initial visit and at follow-up appointments, nurses can provide reassurance and help patients to set realistic goals.115, 116

Three weeks after referring Ms. Cooley to the dietitian, the RN calls Ms. Cooley to check on her progress. Ms. Cooley says she has made some dietary changes for herself and her family. She has noticed that watching what she eats really affects the frequency of her symptoms and has realized how important it is for her to take charge of her health. Accordingly, she has started taking a “restore and relax” class offered locally. The RN makes a three-month follow-up appointment for her with the gastroenterologist and notes that Ms. Cooley is more hopeful now that she can manage her condition.

Ms. Cooley took an active role in her healing by keeping a food and symptom diary and was able to work with her health care provider to track her symptoms. In the relationship between nurses and patients with IBS, trust, support, and availability can greatly improve clinical outcomes.

Figure 1.

IBS symptoms are not limited to the GI system. People with IBS often experience nonbowel-related overlapping symptoms and comorbidity that cause distress and negatively impact quality of life. Illustration by Mike Linkinhoker. Copyright © 1998–2003 by The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation; used with permission; www.hopkins-gi.org.

Figure 2.

IBS physiology involves complex interactions among the brain, the neuroendocrine system, and the gut. Illustration by Anne Rains.

Footnotes

The authors and planners have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

For 41 additional continuing nursing education articles on gastrointestinal topics, go to www.nursingcenter.com/ce.

Contributor Information

Joyce K. Anastasi, Independence Foundation endowed professor and founding director of the Division of Special Studies in Symptom Management (DS3M), New York University College of Nursing, New York City

Bernadette Capili, Assistant professor and associate director of the DS3M, and Michelle Chang is a research associate at the DS3M, New York University College of Nursing, New York City.

References

- 1.American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome, et al. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 1):S1–S35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews EB, et al. Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large web-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(10):935–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman D, editor. Rome III: the functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Effect of gender on prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):991–1000. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitehead WE, et al. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):1140–56. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal N, Spiegel BM. The effect of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life and health care expenditures. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inadomi JM, et al. Systematic review: the economic impact of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(7):671–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.t01-1-01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longstreth GF, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome, health care use, and costs: a U.S. managed care perspective. Am J Gas−troenterol. 2003;98(3):600–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiegel BM. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11(4):265–9. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiBonaventura M, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity and health care resource use associated with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(11):2213–22. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.623157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drossman DA, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gas−troenterol. 2009;43(6):541–50. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Gastroenterological Association. The burden of gastrointestinal diseases. Bethesda, MA: 2001. http://www.lewin.com/~/media/lewin/site_sections/publications/2695.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang JY, Talley NJ. An update on irritable bowel syndrome: from diagnosis to emerging therapies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27(1):72–8. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283414065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohman L, Simren M. Pathogenesis of IBS: role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions. Nat Rev Gas−troenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(3):163–73. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simrén M, et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2013;62(1):159–76. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford AC, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(12):1279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiller R, Lam C. An update on post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: role of genetics, immune activation, serotonin and altered microbiome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18(3):258–68. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.3.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford AC, et al. Yield of diagnostic tests for celiac disease in individuals with symptoms suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):651–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalantar JS, et al. Familial aggregation of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Gut. 2003;52(12):1703–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito YA, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome aggregates strongly in families: a family-based case-control study. Neurogastro−enterol Motil. 2008;20(7):790–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.1077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito YA. The role of genetics in IBS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):45–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gros DF, et al. Frequency and severity of the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome across the anxiety disorders and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2):290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladabaum U, et al. Diagnosis, comorbidities, and management of irritable bowel syndrome in patients in a large health maintenance organization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Locke GR, 3rd, et al. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(2):350–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palsson OS, Drossman DA. Psychiatric and psychological dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome and the role of psychological treatments. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(2):281–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitehead WE, et al. Comorbidity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(12):2767–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang L. The role of stress on physiologic responses and clinical symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenter−ology. 2011;140(3):761–5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choung RS, et al. Psychosocial distress and somatic symptoms in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: a psychological component is the rule. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(7):1772–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camilleri M. Do the symptom-based, Rome criteria of irritable bowel syndrome lead to better diagnosis and treatment outcomes? The con argument Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;8(2):129. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome: how useful is the term and the ‘diagnosis’? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5(6):381–6. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12442223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laine C, et al. In the clinic: irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(1):ITC7-1–ITC7-16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-01007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucak S. Diagnosing irritable bowel syndrome: what’s too much, what’s enough? MedGenMed. 2004;6(1):17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall JK, et al. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome after a food-borne outbreak of acute gastroenteritis attributed to a viral pathogen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(4):457–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spiller R, Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(6):1979–88. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talley NJ, et al. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(11):2454–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lembo TJ, Fink RN. Clinical assessment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(1 Suppl):S31–S36. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cash BD, et al. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(11):2812–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spiegel BM, et al. Is irritable bowel syndrome a diagnosis of exclusion?: a survey of primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and IBS experts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):848–58. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American College of Gastroenterology. Understanding irritable bowel syndrome. 2003 http://patients.gi.org/gi-health-and-disease/understanding-irritable-bowel-syndrome.

- 40.Whitehead WE, et al. The usual medical care for irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(11–12):1305–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Schryver AM, et al. Effects of regular physical activity on defecation pattern in middle-aged patients complaining of chronic constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(4):422–9. doi: 10.1080/00365520510011641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johannesson E, et al. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(5):915–22. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villoria A, et al. Physical activity and intestinal gas clearance in patients with bloating. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(11):2552–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herring MP, et al. The effect of exercise training on anxiety symptoms among patients: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):321–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rimer J, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heizer WD, et al. The role of diet in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a narrative review. J Am Diet As−soc. 2009;109(7):1204–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shepherd SJ, et al. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(7):765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biesiekierski JR, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):508–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bahar RJ, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of am-itriptyline for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents. J Pediatr. 2008;152(5):685–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Camilleri M, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of the serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist alosetron in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(14):1733–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.14.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chey WD, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of alosetron in women with severe diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(11):2195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drossman DA. Beyond tricyclics: new ideas for treating patients with painful and refractory functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(12):2897–902. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drossman DA, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome— results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):329–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Drossman DA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(1):19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00669-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ford AC, et al. Efficacy of 5-HT3 antagonists and 5-HT4 agonists in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(7):1831–43. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ford AC, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58(3):367–78. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khoshoo V, et al. Effect of a laxative with and without tega-serod in adolescents with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(1):191–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krause R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled study to assess efficacy and safety of 0. 5 mg and 1 mg alosetron in women with severe diarrhea-predominant IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1709–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ladabaum U, et al. Citalopram provides little or no benefit in nondepressed patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(1):42–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lembo AJ, et al. Effect of alosetron on bowel urgency and global symptoms in women with severe, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: analysis of two controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(8):675–82. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masand PS, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo- controlled trial of paroxetine controlled-release in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(1):78–86. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pimentel M, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):22–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pimentel M, et al. The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(8):557–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prometheus Laboratories. Highlights of prescribing information: Lotronex (alosetron hydrochloride) tablets. San Diego: 2010. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021107s016lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saad RJ. Peripherally acting therapies for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):163–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sainsbury A, Ford AC. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: beyond fiber and antispasmodic agents. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4(2):115–27. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10387203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharara AI, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo- controlled trial of rifaximin in patients with abdominal bloating and flatulence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(2):326–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tack J, et al. A controlled crossover study of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55(8):1095–103. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.077503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takeda Pharmaceuticals America. Highlights of prescribing information: Amitiza (lubiprostone) capsules. Deerfield, IL: 2012. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/021908s010lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 70.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Zelnorm (tegaserod maleate) information. Silver Spring, MD: 2007. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm103223.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vahedi H, et al. The effect of fluoxetine in patients with pain and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind randomized-controlled study. Aliment Pharma−col Ther. 2005;22(5):381–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watson ME, et al. Alosetron improves quality of life in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(2):455–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brandt LJ, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(Suppl 1):S5–S21. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ruepert L, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Co−chrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chey WD, et al. Safety and patient outcomes with lubiprostone for up to 52 weeks in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(5):587–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. NME drug and new biologic approvals in 2002. Silver Spring, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang HY, et al. Current gut-directed therapies for irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9(4):314–23. doi: 10.1007/s11938-006-0013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bleser S. Alosetron for severe diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: improving patient outcomes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(3):503–12. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.547933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dekel R, et al. The use of psychotropic drugs in irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22(3):329–39. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.761205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vahedi H, et al. Clinical trial: the effect of amitriptyline in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(8):678–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Drossman DA, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II25–II30. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zijdenbos IL, et al. Psychological treatments for the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006442. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006442.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lackner JM, et al. Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1100–13. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lackner JM, et al. Rapid response to cognitive behavior therapy predicts treatment outcome in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(5):426–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jarrett ME, et al. Comprehensive self-management for irritable bowel syndrome: randomized trial of in-person vs. combined in-person and telephone sessions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(12):3004–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Psychological treatments in functional gastrointestinal disorders: a primer for the gastroenterologist. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(3):208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wilson S, et al. Systematic review: the effectiveness of hypnotherapy in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(5):769–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith GD. Effect of nurse-led gut-directed hypnotherapy upon health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(6):678–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chapman W. Hypnotherapy as a treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2004;2(2):23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giese LA. A study of alternative health care use for gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2000;23(1):19–27. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koloski NA, et al. Predictors of conventional and alternative health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(6):841–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whelan K, Quigley EM. Probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29(2):184–9. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835d7bba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.O’Mahony L, et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(3):541–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whorwell PJ, et al. Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1581–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cappello G, et al. Peppermint oil (Mintoil) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective double blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(6):530–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu JH, et al. Enteric-coated peppermint-oil capsules in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(6):765–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02936952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Merat S, et al. The effect of enteric-coated, delayed-release peppermint oil on irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(5):1385–90. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0854-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Therapeutic Research Faculty. Natural medicines comprehensive database: peppermint oil. 2012 http://www.naturaldatabase.com.

- 99.Ezzo JM, et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD002285. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee A, Fan LT. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Co−chrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD003281. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang SM, et al. Acupuncture analgesia: I. The scientific basis. Anesth Analg. 2008;106(2):602–10. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000277493.42335.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goldman N, et al. Adenosine A1 receptors mediate local anti-nociceptive effects of acupuncture. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(7):883–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hui KK, et al. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;27(3):479–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fireman Z, et al. Acupuncture treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. A double-blind controlled study. Digestion. 2001;64(2):100–3. doi: 10.1159/000048847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Forbes A, et al. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: a blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(26):4040–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lembo AJ, et al. A treatment trial of acupuncture in IBS patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1489–97. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schneider A, et al. Acupuncture treatment in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55(5):649–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lim B, et al. Acupuncture for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005111. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005111.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gaylord SA, et al. Mindfulness training reduces the severity of irritable bowel syndrome in women: results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(9):1678–88. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zernicke KA, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2012 May 23; doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9241-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Naliboff BD, et al. Toward a biobehavioral model of visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. J Psy−chosom Res. 1998;45(6):485–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Verne GN, et al. Hypersensitivity to visceral and cutaneous pain in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2001;93(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Halpert A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome patients’ ideal expectations and recent experiences with healthcare providers: a national survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):375–83. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Halpert A, Godena E. Irritable bowel syndrome patients’ perspectives on their relationships with healthcare providers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(7–8):823–30. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.574729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bodenheimer T, et al. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(12):1097–102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]