Summary

Secreted aspartic proteases (Saps) represent an important virulence factor facilitating fungal adherence. Several protease inhibitors (PIs), including HIV PIs, have been shown to reduce Candida adhesion. The aim of this study was to ascertain whether or not the recently discovered PIs Aureoquinone and Laccaridiones A and B, isolated from Basidiomycete cultures, or Bestatin, act as Sap-inhibitors and/or inhibitors of fungal adhesion. Drug effects on candidial Sap-production were determined by Sap-ELISA. Control tubes, in the absence of drug, served as positive controls, while tubes excluding both drug and proteinase induction medium were used as negative controls. Aureoquinone as well as Laccaridiones A and B, but not Bestatin, significantly inhibited Candida albicans adhesion to both epithelial and endothelial cells in a dose dependent manner and also reduced Sap-release (effects were not because of a direct interaction of the Basidiomycete metabolites with secreted Saps). Laccaridione B was consistently found to be the most effective PI tested. Interestingly, these drugs are neither fungistatic nor fungicidal at the concentrations applied. Laccaridione B may represent a promising novel type of antimycotic drug – targeting virulence factors without killing the yeast.

Keywords: Candida, protease inhibitor, adhesion, Sap release, viability, Basidiomycetes

Introduction

Candida albicans represents the medically most important Candida species.1 It can act both as a commensal (mostly of mucosal surfaces, especially those with low pH)2 and as an endogenous opportunist, capable of initiating morbidity when the cellular immune defence is weakened. This does not necessarily imply severe impairment of immune function, as any alteration in any antimicrobial defence leads to (sometimes merely subtle) changes in the balance of pathogenicity and host defences3 and the extent of host defence compromise can be very small (as e.g. in Candida vulvovaginitis).

The propensity of the yeast to cause morbidity is largely dependant on the virulence factors displayed. These are the results of concerted action of a multiplicity of genes, the expression of which also depends on the tissue infected and the stage of infection.4 Of the multitude of virulence factors discovered in recent years, secreted aspartic proteinases (Saps) have attracted considerable interest. They are single chain bilobal structures with two domains separated by a large cleft, at the base of which the catalytic centre resides and all oligopeptide inhibitors bind.5 Candidial Saps are located in membrane bound vesicles in the membrane fraction.6 A direct correlation between virulence and levels of Sap production was first suspected by Staib [7] in 1969 (who also first described extracellular proteolytic activity of Candida8) and demonstrated in 1986.9 Sap production enhances the ability of the organism to adhere, colonise and penetrate host tissues and to evade the host immune system, which is accounted for by the broad substrate specificity.9–13 Fungal proteases, and possibly Saps as well, inhibit cell-bound as well as humoral immunity (by degrading immunoglobulin and complement, involved in the critical regulation of various cascade systems and inflammatory response.11,14) To date, at least 10 Sap-isoenzymes have been described, all encoded by separate genes, which are regulated differentially during the course of infection.10 The specific Sap isoenzyme pattern is determined by cell type/strain, phenotypic switching, yeast to mycelium transition, stages of infection and tissue sites during infection, while the level of Sap production is affected by environmental factors (such as medium, pH, temperature and the presence of NH4+).15 In short, Saps are responsible for a multitude of virulence mechanisms of C. albicans, making the importance of finding a Sap-specific inhibitor evident.

Aureoquinone16 and Laccaridione A and B17 are newly discovered protease inhibitors (PIs) isolated from Basidiomycetes strains. In view of the ongoing search for antifungal therapeutics, the aim of this study was to test these novel bioactive substances for their ability to inhibit C. albicans Sap-production and/or activity, and to assess whether there is a correlation with the ability of the yeast to adhere to human epithelial and/or endothelial cells or not. Inhibitors of adhesion would be very attractive as novel drugs as they may block infection at the portal of entry of the infectious microorganism.

Materials and methods

Epithelial cell culture

The human cervix carcinoma cell line HeLa S3 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA), used as a model for mucosal candidiasis, was cultivated in 12 ml HAM’s F12 medium (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Linz, Austria) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; PAA Laboratories) and 1% L-glutamine (Invitrogen Corporation, Paisley, UK) in Costar cell culture flasks (Costar 3375, 75 cm3; Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity (Heraeus Incubator RB500; W.C. Hereaus, Hanau, Germany). The medium was exchanged every 2 or 3 days after rinsing with 10 ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and the cells were transferred into new culture flasks every 5 or 7 days; cells were detached with 10 ml of 5 mmol l−1 EDTA-dissociation solution as described in detail elsewhere.18

Endothelial cell culture

The endothelial cell line EAhy 926,19 a hybridome of lung carcinoma cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells, used as a model for systemic candidiasis, was cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen Corporation) supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% l-glutamine under the same conditions as the aforementioned epithelial cells. The cells were removed from the culture vessel with trypsin solution as described elsewhere.18

Candida albicans cultivation

Candida albicans CBS 5982 (Central Bureau voor Schimmelculturen, Baarn, The Netherlands) was used throughout the study as preliminary investigations yielded identical results with clinical strains and CBS 5982. The original material was suspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Steinheim, Germany) and stored at −80 °C. For the experiments, Candida cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 and incubated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates (mycological peptone 10.0; d(+)glucose 40.0; Agar 15.0; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) for 24–48 h at 30 °C. After sufficient growth, the plates were stored at 4 °C. Subcultures were performed weekly. For preparation of yeast cell suspensions, Candida was harvested from the agar dishes and suspended in non-supplemented RPMI 1640 medium at the appropriate concentrations (2 × 104 cells ml−1 for the adherence assay; 1 × 108 cells ml−1 for the Sap-ELISA; the final concentrations reached after addition of the PI-solutions and the Sap-inducing medium (only for Sap-ELISA) were 1 × 104 cells ml−1 or 1 × 107 cells ml−1, respectively).

Proteinase inhibitors

Purified Aureoquinone, a metabolite of Aureobasidium spp,16 was dissolved in methanol at a concentration of 1 mg ml−1. Purified Laccaridiones A and B, isolates from the Basidiomycete strain Laccaria amethysthea,17 were dissolved in methanol at 0.5 mg ml−1. Bestatin ([(2S,3R)-3-amino-3-hydroxy-4-phenyl-butanoyl]-l-leucin)20 was dissolved in methanol at a concentration of 1 mg ml−1. All solutions were used as stock-solutions and stored at 4 °C. To assay the concentration dependence of the effects of above mentioned PIs for the adherence assay, they were first added to whole growth medium (supplemented HAM’s or RPMI 1640, depending on which cell line was used), beginning with a concentration of 100 μg ml−1. The substance concentration was then fivefold diluted in the respective growth medium in four steps. Final concentrations reached after addition of the prepared Candida suspension at a ratio of 1 : 2 were 50, 2, 0.4 and 0.08 μg ml−1 for all substances.

Indinavir (Merck, New York, NY, USA), a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-PI, was dissolved in deionised water at a concentration of 40 mmol l−1 and stored at −20 °C. It was used at a concentration of 0.1 mmol l−1 for detection of Sap-activity.

For the Sap-ELISA, the PIs were added to and diluted in 0.9% NaCl at the same final concentrations as above.

Fungal viability testing

Candida albicans was incubated with the dissolved drugs or the solvent alone for up to 4 h at 37 °C and was plated using a spiral platter, essentially as described elsewhere.21 The colony forming units (CFU) were assessed after overnight culture.

Adherence assay

Detached cells (100 μl suspended in the appropriate supplemented growth medium: HAM’s for HeLa S3, RPMI 1640 for EAhy 926) at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells ml−1 were inoculated into each well of a flat-bottomed 96-well plate (Costar; Corning) and grown to a confluent monolayer (at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity, for 24 h) according to published methods.19 Confluence was assessed by visual inspection prior to addition of yeasts. Candida albicans (2 × 104 cells ml−1) and various concentrations of PIs were mixed at a ratio of 1 : 2. Candida without PIs, in the absence or presence of the appropriate percentage of methanol (depending on the solubility of the former in the latter) served as controls. The controls without methanol were set to 100%. All preparations were incubated at 37 °C (without CO2) for 1 h. The wells of the microtiter plate containing HeLa S3 or EAhy 926 cells, respectively, were washed with 150 μl PBS per well and then subjected to 100 μl of the preincubated Candida-PI solution for 30 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity. Subsequently all wells were washed twice to remove non-adherent yeasts and 100 μl of liquid SDA was added to each well. After further incubation for 16 h, enumeration of CFU of monolayer-attached yeasts was performed visually under microscopic control at a magnification of 40×. Three replicate experiments were performed.

Induction of secreted aspartic proteinases

To assess drug effects on candidial Sap-production, 100 μl of a 1 × 108 yeast cell ml−1-suspension were grown in the presence or absence of the drug in 1 ml of proteinase induction medium (PIM: 2% glucose, 0.1% KH2PO4, 0.05% MgSO4; dissolved in deionised water, adjusted to pH 4.0, steam sterilised) supplemented with minimal essential medium vitamins (Sigma, 1% of 100×) and 10% (v/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) (dissolved in PIM). Control tubes (Cellstar 15 ml; Greiner, Kremsmünster, Austria) without inhibitor, containing methanol as used for dissolving the drug, were performed in parallel to determine the effects solely attributable to the latter. Control tubes without drug but with PIM served as positive control (CBS 5982 in PIM supplemented with BSA and vitamins; high Sap-production), whereas tubes without drug, BSA and vitamins were used as negative controls (no Sap-production). All concentrations were simultaneously tested in duplicates (in separate tubes). These were incubated at 22 °C for 8 days on a test tube rotator (Snijders Scientific, Tilburg, Holland), to prevent the fungus from adhering to the plastic tubes, with or without addition of drug in the appropriate concentrations every 48 h (NaCl or methanol, respectively, were added to the controls in the appropriate concentrations). This relatively long experimental duration time has previously been shown to be required for sufficient Sap production.22

Subsequent to centrifugation at 1200 g for 10 min, the supernatant was assayed for proteinase concentration (determined by Sap-ELISA) and activity [via degradation of BSA, determined by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacryl gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequent Coomassie staining or western blot, detailed below].

Secreted aspartic proteinase ELISA

The amount of Sap-release was determined by direct ELISA. Each well of a 96-well ELISA plate (F-form, high binding capacity; Greiner) was coated with 80 μl aliquots of the Sap-containing supernatants (obtained as described in Induction of secreted aspartic proteinases) and 20 μl of coating buffer (0.2 mol l−1 NaHCO3, 0.2 mol l−1 Na2CO3 dissolved separately in deionised water; 740 ml of the former + 260 ml of the latter; stored at 4 °C) and incubated at 4 °C for 16 h, covered with parafilm M (American National Com, Chicago, IL, USA). PBS-Tween (T) (0.05% Tween 20) was used as reference value (negative control) and purified Sap served as positive control. After rinsing with 150 μl PBS-T per well to remove non-bound protein, 130 μl 1% gelatine (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) dissolved in coating buffer was applied to each well for 30 min at room temperature in a moist chamber, to block possible unspecific binding sites. After washing, antigen detection was accomplished by adding 100 μl to every well of the first antibody (monoclonal mouse IgG FX 7-10,23 which is directed against an epitope on Sap2, diluted in PBS-T at 2 μg ml−1) and incubation for 1 h in a moist chamber. Non-bound antibodies were removed by washing thrice and a secondary alkaline phosphatase conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antibody (Sigma) diluted in PBS-T at a concentration of 1 μg ml−1 was added and incubated for 1 h under the above mentioned conditions. After washing three times, 100 μl substrate per well [1 p-nitrophenylphosphate tablet (Sigma)/5 ml alkaline phosphatase buffer (0.1 mol l−1 glycin, 1 mmol l−1 MgCl2, 1 mmol l−1 ZnCl2 in aqua distillate, pH 10.4)] was added and substrate turnover was measured at 405 nm vs. 492 nm in an ELISA-reader (Asys Hitech, Eugendorf, Austria). Three replicate experiments were performed.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacryl gel electrophoresis

Culture supernatants of C. albicans grown in the absence or presence of drugs in supplemented PIM, as well as the positive and negative controls (see Induction of secreted aspartic proteinases above), were assessed for proteinase activity and its inhibition by PIs. One thousand and two hundred microlitre of the supernatant containing Laccaridione B at concentrations of 50 and 10 μg ml−1, with the respective appropriate concentrations of methanol (as used for dissolving the drug), was incubated with 1% BSA as substrate (dissolved in deionised water and adjusted to pH 3.2 to attain the pH-optimum for Sap) for 15 or 30 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity. BSA in the absence of drug and without added supernatant served as control. In parallel, 600 μl of the ‘positive’ tube containing high quantities of Sap [as demonstrated by prior performed Sap-ELISA (see Secreted aspartic proteinase ELISA)] was incubated with 400 μl of 1% BSA (in deionised water, pH 3.2) containing the desired concentrations of drugs (50 and 30 μg ml−1 Laccaridione B), or freshly added Indinavir (0.1 mmol l−1), which served as control (the effectiveness of Indinavir in preventing the degradation of BSA has previously been shown by Cassone et al. [24]). After incubation, a 5-μl aliquot of each mixture was subjected to SDS-PAGE at 4 °C.18

Two assays were performed in parallel. One with (reduced) and one without (unreduced) mercaptoethanol in the application buffer. The molecular weight of the BSA cleavage products was compared with molecular weight markers, which were run in adjacent lanes. Proteins separated by gel electrophoresis were localised by staining with Coomassie blue (Merck) for approximately 30 min under gentle agitation.

Western blot

The specificity of the SDS-PAGE for the proteolytic activity of Sap with reference to BSA was confirmed by Western blot. The transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane was carried out at constant current (400 mA) for 2 h at 4 °C. The membrane was blocked using 3% skim milk (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) dissolved in PBS over night, at room temperature, on an orbital shaker platform to saturate the binding sites prior to incubation with antibodies. The blots were then washed with PBS-T for 10 min and subsequently overlaid, for 1 h under gentle agitation, with a sufficient volume of primary antibody [rabbit anti-BSA IgG; (Sigma) diluted in PBS at a concentration of 20 μl ml−1]. The blot was then washed twice for 10 min each, before it was overlaid with the secondary alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma) diluted in PBS at a ratio of 1 : 10 000, and incubated for 1 h under gentle agitation. After three washings, the blot was developed with the adequate amount of substrate [1 BCIP/NBT tablet (Sigma)/10 ml deionised H2O] for 10 min under gentle agitation in the dark. After three washings with deionised H2O, the blot was air-dried and stored in the dark.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using spss for Windows version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Birmingham, UK). Statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05, highly significant P ≤ 0.01) was determined using Student’s t-test analysis. All comparisons were two-sided.

Results

Effects of Basidiomycetes metabolites on fungal viability

Neither the recently discovered PIs Aureoquinone and Laccaridiones A and B, isolated from Basidiomycete cultures, nor Bestatin, nor methanol in which the drugs were dissolved had any effect on fungal growth at the concentration applied in the adhesion and Sap experiments, as assessed by spiral platter plating experiments (data not shown).

Effects of Basidiomycetes metabolites on candidial adherence

The recently discovered PIs Aureoquinone and Laccaridiones A and B, isolated from Basidiomycete subcultures, as well as the well known PI Bestatin, were investigated with respect to their effects on the adherence of C. albicans (CBS 5982) to epithelial (HeLa S3) and endothelial (EAhy 926) cells.

Aureoquinone was observed to cause a significant dose dependant inhibition of adherence to epithelial cells at concentrations ≥0.4 μg ml−1 (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Effect of Aureoquinone on CBS 5982 adherence to HeLa S3. The light grey bars mark controls, containing solely the same percentage of methanol as used for dissolving the drug at that concentration (namely, 5% for 50 μg ml−1, 1% for 10 μg ml−1 and 0.2% for 2 μg ml−1). Data shown represent mean ± SD of five experiments. **: highly significant (P ≤ 0.01); statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test analysis. (b) Effect of Laccaridione A on CBS 5982 adherence to HeLa S3. Methanol was 10% at a drug concentration of 50 μg ml−1, 2% at 10 μg ml−1 and 0.4% for 2 μg ml−1 respectively. Data shown represent mean ± SD of three experiments. **: highly significant (P ≤ 0.01); *: significant (P ≤ 0.05). (c) Effect of Laccaridione B on CBS 5982 adherence to HeLa S3. Details as described in (b). (d) Effect of Laccaridione B on CBS 5982 adherence to EAhy 926. Details as described in (b).

Laccaridione A, the bioactive metabolite of Laccaria amethysthea, was shown to induce a dose-dependant, significant reduction in adherence to HeLa S3 already at a concentration as low as 0.08 μg ml−1 (Fig. 1b). The highly significant inhibition (P ≤ 0.01) of 35% at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 of Laccaridione A is at most only minimally attributable to methanol, used for dissolving the drug, as the inhibition for the control containing solely 2% methanol was found to be non-significant (Fig. 1b). The marked reduction in adherence observed at 50 μg ml−1 of Laccaridione A, however, is most likely largely attributable to the effect of the high percentage of methanol (10%) present at this concentration, abolishing adherence, but not viability (see Effects of Basidiomycetes metabolites on fungal viability). This is in concordance with our previous data.25

Laccaridione B displayed a highly significant reduction in C. albicans adherence to epithelial cells already at a concentration of 0.4 μg ml−1 (Fig. 1c), which is probably exclusively attributable to the effects of Laccaridione B but not to those of methanol, the drug solvent. Methanol, however, inhibits adherence at a concentration of 10%, the concentration at which it is present in the 50 μl Laccaridione B solution. Furthermore, Laccaridione B has, in addition, a direct toxic effect on HeLa cells.17 The inhibitory effect of Laccaridione B on candidial adherence to the endothelial cell line EAhy 926 (Fig. 1d) was comparable to or possibly even greater than that observed for adherence to HeLa S3 (Fig. 1c). A 66% reduction in adherence to endothelial cells was documented at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 Laccaridione B (compared to 56% for epithelial cells, both P ≤ 0.01), of which merely approximately 23% was attributable to the effect of methanol.

Bestatin only slightly reduced adherence of C. albicans to epithelial (HeLa S3) or endothelial (EAhy 926) cells, in a non-dose-dependant and insignificant manner (data not shown).

Effects of Basidiomycetes metabolites on secreted aspartic proteinase-release

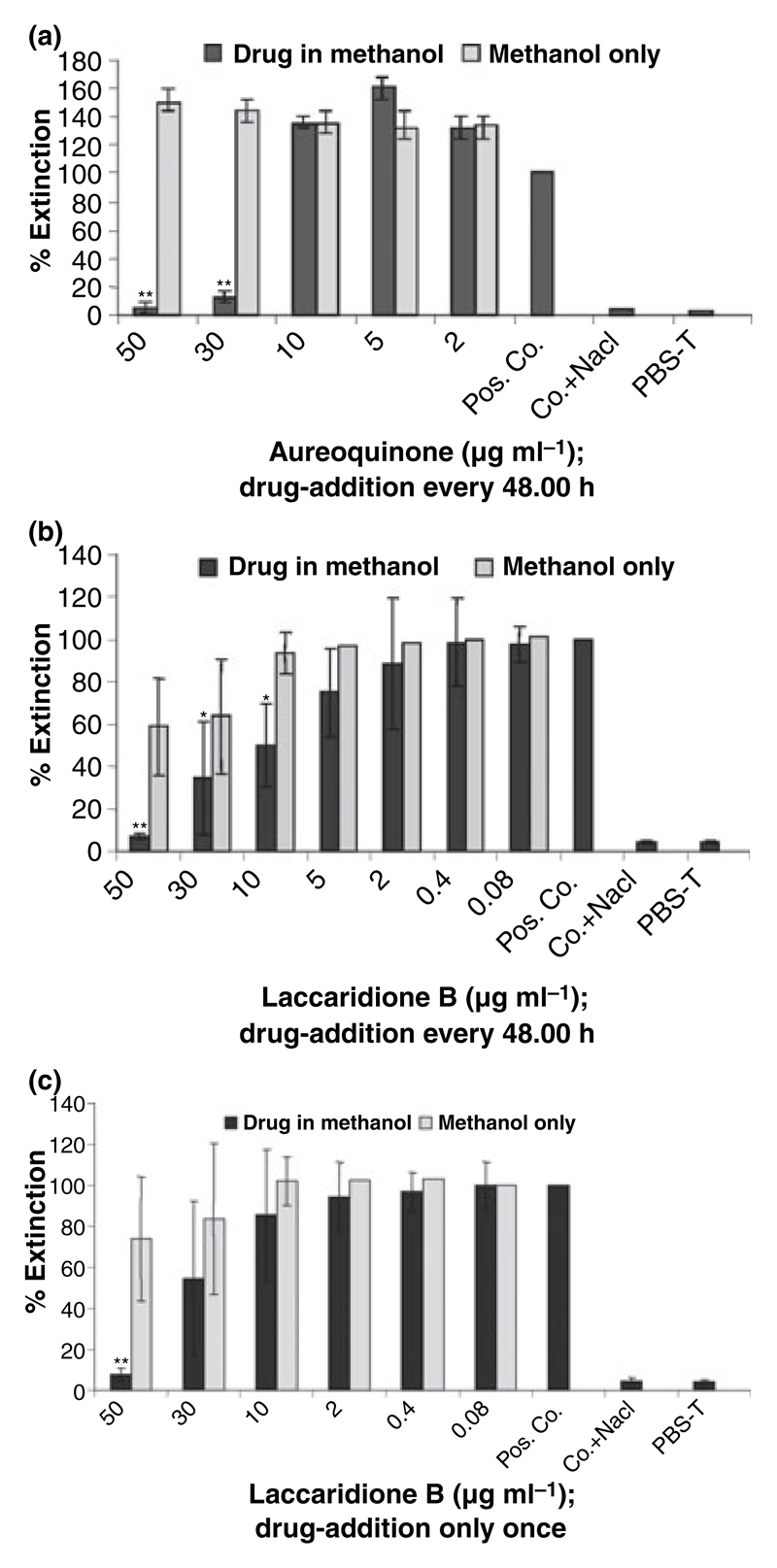

The effects of the drugs on Sap-release of CBS 5982 were determined by ELISA after incubation in the induction medium for 8 days in the absence or presence of PIs, in the appropriate concentration of methanol or NaCl, respectively. All PIs and control substances were added every 48 h. No marked difference was observed in the resulting cell numbers in the induced samples after 8 days (data not shown). The extensive reduction in Sap-release of CBS 5982 by Aureoquinone at concentrations of 50 and 30 μg ml−1 is attributable to an effect brought about by the Basidiomycete metabolite itself and not the drug diluent, methanol (P ≤ 0.01; Fig. 2a). A more pronounced and clearly dose dependant effect was achieved with Laccaridione B (Fig. 2b). In the latter case, a significant reduction in Sap-release of 50% was detected at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 Laccaridione B. A 65% reduction in detectable Sap occurred at a concentration of 30 μg ml−1 of Laccaridione B and a highly significant reduction of 93% was detected at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1 (P ≤ 0.01; Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Effect of Aureoquinone on Sap-release of CBS 5982. Drug addition was performed every 48 h. The percentage of methanol used for dissolving the drug was 5% for a Aureoquinone concentration of 50 μg ml−1 and 3% for 30 μg ml−1. Pos. Co. denotes positive control of CBS 5982 in Sap-induction medium; Co. + NaCl denotes control + NaCl and served as negative control along with PBS-T. Extinction was determined at 405 nm with a reference wave length of 492 nm. Data shown represent mean ± SD of four experiments. **: highly significant (P ≤ 0.01); *: significant (P ≤ 0.05); statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test analysis. (b) Effect of Laccaridione B on Sap-release of CBS 5982. The percentage of methanol used for dissolving the drug was 10% for a Laccaridione B concentration of 50 μg ml−1, 6% for 30 μg ml−1 and 2% for 10 μg ml−1. Further details are as described in (a). (c) Effect of Laccaridione B on Sap-release of CBS 5982. Drug addition was performed once only at the start of the experiment.

In parallel, a similar set-up was performed in which the drug was added merely once at the beginning of the 8 day incubation period. The results show a decline in Sap-release at higher concentrations only, with a 50 μg ml−1 drug concentration being the lowest concentration to show a significant effect (Fig. 2c) in contrast to the 10 μg ml−1 drug concentration in the former set up (Fig. 2b), where the substances were added fresh every 48 h. These data underline the importance of maintaining a constant drug level.

Effects of Basidiomycetes metabolites on secreted aspartic proteinase activity

Saps belong to a family of proteolytic enzymes, which degrade a wide range of substances. BSA was used in this study to represent one such substrate. Degradation of BSA is indicative of Sap-activity, while the absence thereof marks Sap-inhibition. To detect Sap-activity and/or its inhibition by Laccaridione B or Indinavir, BSA (1% wt/vol, adjusted to pH 3.2) was incubated for 15 min with the 8-day-incubation supernatants (as obtained in Adherence assay) containing Laccaridione B dissolved in methanol, methanol only (both added every 48 h), or a sample containing neither drug nor methanol but high Sap concentrations. Laccaridione B or Indinavir was also added fresh together with BSA to the 8-day-incubation samples containing high Sap concentrations for comparison. The set-up was carried out with (Fig. 3a) or without (data not shown) adding mercaptoethanol as reducing agent to the application buffer. Comparable results were obtained in both cases, however, inhibition of cleavage seemed less evident in the latter case and the protein bands were better visible in the presence of mercaptoethanol; thus all further experiments were carried out in the reduced status. Sap activity was inhibited by Laccaridione B at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1 (Fig. 3a, lane 4), as indicated by the absence of hydrolysis of BSA (compare Fig. 3a, lane 4 and 10). This effect is not attributable to toxic effects of the drug solvent (=methanol) as no inhibition of Sap activity was observed with the aliquots containing 2% or 10% methanol (Fig. 3a, lanes 1 and 2). The fact that Laccaridione B freshly added to the 8-day-incubation samples (Fig. 3a, lanes 7−8) was not able to inhibit Sap activity underlines the importance of maintaining the level of drug concentration (in vitro achieved by adding the appropriate amount of drug every 48 h), and shows that the effects seen are the result of an inhibition in Sap-production and/or -release and are not because of a direct interaction of the drug with Sap. Unexpectedly, no marked Sap-inhibition could be detected for Indinavir (Fig. 3a, lane 3), despite the use of higher drug concentrations than those used by Cassone et al. [24] in a similar assay.

Figure 3.

(a). Sap expression and PI activity determined by BSA cleavage of supernatants derived from CBS 5982 incubated for 8 days in PIM supplemented with BSA and vitamins in the absence or presence of PI or methanol (SDS-PAGE). Lanes 1 and 2, plus 2% and 10% methanol, respectively; 3, plus Indinavir [0.1 mmol l−1]; 4 and 5, plus Laccaridione B at concentrations of 50 μg ml−1 and 10 μg ml−1, respectively; 6, molecular weight standards (kDa); 7 and 8, plus freshly added Laccaridione B applied to the 8-day-incubation samples at concentrations of 10 μg ml−1 and 50 μg ml−1, respectively; 9, just BSA with supernatant; 10, just BSA; + denotes visible BSA-cleavage; − denotes inhibition or absence of BSA-cleavage; M denotes molecular weight standards; C denotes control. (b) Sap expression and PI-activity determined by BSA cleavage of supernatants derived from CBS 5982 incubated for seven days in PIM supplemented with BSA and vitamins in the absence or presence of PI or methanol (SDS-PAGE and western blot). Lane 1, molecular weight standard (kDa); 2 and 3, plus freshly added Laccaridione B applied to the 8-day-incubation samples at drug concentrations of 50 μg ml−1 and 10 μg ml−1, respectively; 4 and 5, plus Laccaridione B at concentrations of 50 μg ml−1 and 10 μg ml−1, respectively; 6, BSA only; 7, plus freshly added Indinavir [0.1 mmol l−1]; 8, BSA with CBS 5982 and PIM (=control); 9 and 10, plus 10% and 2% methanol, respectively; + denotes visible BSA-cleavage; − denotes inhibition or absence of BSA-cleavage; M denotes molecular weight standards; C denotes control.

It is clear that the supernatants used (obtained as described in Induction of secreted aspartic proteinases) do not only contain the added BSA as possible substrate, but also diverse metabolites of the fungus. To determine whether or not the protein bands observed in Fig. 3a truly represent degraded or non-degraded BSA, as the case may be, we carried out western blot analyses using an anti-BSA-antibody. As the protein bands were rather broad because of high protein concentrations in the samples (in Fig. 3a), the western blot was carried out with application of 10 μl aliquots to the gel (as opposed to the 40 μl aliquots used in the protein stained gels, which was in accordance with the method used by Cassone et al. [24]). Additionally, the incubation period was increased to 30 min to see if this would effect inhibition of Sap activity by the freshly added substances (the results, however, remained the same). The western blot results (Fig. 3b) confirmed those of the stained gels (Fig. 3a), but were much clearer because of the smaller aliquots used. Supernatants containing concentrations of 50 and 10 μg ml−1 Laccaridione B showed no hydrolysis of BSA or reduced hydrolysis, respectively, thus proving an inhibition of Sap release at these concentrations (Fig. 3b, lanes 4 and 5). This effect cannot be attributed to the presence of methanol, which was used for dissolving the drug (Fig. 3b, lanes 9 and 10). As in the previous set-ups, freshly added Laccaridione B added to the 8-day-incubation samples was not able to inhibit Sap-activity, despite the incubation period of BSA, Sap supernatant and drug being increased to 30 min (Fig. 3b, lane 2).

Discussion

To date, antifungal drug design has predominantly been based on targeting a singular cellular metabolic or biosynthetic process. However, because of frequent relapses and the ever-rising emergence of drug resistance,26 this strategy appears to be inadequate and the pressing demand for new approaches to drug discovery can no longer be neglected. The objective of this study was to target fungal virulence factors, with blockage of adhesion being the specific focus of attention. Aureoquinone, the newly discovered metabolite of Aureobasidium spp., reduced adhesion of the C. albicans strain CBS 5982 to epithelial cells by 34% at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1, with part of this effect being attributable to the drug diluent methanol (Fig. 1a). Laccaridiones A and B, newly found PIs from the Basidiomycete strain Laccaria amethystea, were found to be distinctly more potent in their inhibitory effect on fungal adherence than Aureoquinone. A highly significant reduction in adherence of 35% (a small part of this effect being attributable to methanol; Fig. 1b) was found for Laccaridione A at 10 μg ml−1. Laccaridione B caused a markedly stronger reduction in candidial adherence to epithelial cells of 56% (Fig. 1c; part of this effect resulting from the influence of methanol), as well as a highly significant 66% reduction in adherence of CBS 5982 to endothelial cells (Fig. 1d). According to these data, Laccaridione B may be slightly more effective in inhibiting the adhesion of C. albicans to endothelial cells than to epithelial cells.

The Sap gene family can be roughly divided into two subfamilies27 represented by Saps 1–3, which contribute to mucosal infections and play an important role in the development of initial lesions during early stages of infection, and Saps 4–6, which play a role in invasive/systemic candidiasis and seem to be important for interactions of the fungus with cells of the immune system.28 We speculate that Laccaridione B not only inhibits Saps 1–3 (which play a major role in the adhesion to epithelial cells),29 but also affects Saps 4–6 (which play a role in systemic candidiasis).28 Further studies are required to clarify this issue. A specific Sap2-antibody was chosen to detect levels of Sap-release in this study, as most C. albicans strains predominantly secrete Sap2.15

This is the first study addressing antifungal effects of Basidiomycete metabolites. Having found strong inhibitory effects of the investigated Basidiomycete metabolites on candidial adhesion, their role in Sap-release and activity was subsequently investigated. Saps are engaged in a multitude of fungal virulence mechanisms, one of which is fungal adherence. Of the substances tested in this study, Laccaridione B had proven to be the most effective in reducing Sap-release of CBS 5982, whereas the presence of Aureoquinone only affected Sap-release at the two highest concentrations investigated. Effects of Laccaridione B on Sap-activity were observed to be inhibitory at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1, where visible BSA-hydrolysis was completely inhibited [Fig. 3, lane 4 (complete inhibition)]. This effect on Sap-activity was not because of a direct interaction between the Basidiomycete metabolite and Sap, but because of inhibition of Sap-production and/or -release. The mechanism of action of this inhibition, e.g. by inhibition of mRNA-synthesis, protein biosynthesis, post-transcriptional modification(s), exocytosis or interference with second messenger signal chains, remains to be elucidated. It appears noteworthy that methanol, the diluent, was observed to have less effect on Sap-release of CBS 5982 than on adherence of CBS 5982 to epithelial (HeLa S3) and endothelial (EAhy 926) cells, with no effect whatsoever on Sap-activity and viability.

It should be borne in mind that the inhibition of adherence of C. albicans to epithelial and endothelial cells, a main focus of interest in this study, may be strongly cell type dependant, as observed for the Sap-release inhibition by HIV PIs.30 However, in contrast to investigations into the effects of HIV PIs on adherence of C. albicans to epithelial and endothelial cells,30 inhibition of adhesion of C. albicans to epithelial cells by the Basidiomycete metabolites investigated here was, although slightly weaker, comparable with that observed for endothelial cells.

Important, particularly in view of the increasing incidence of non-C. albicans species causing clinically manifest candidiasis, is that the Saps in the various Candida spp. are divergent.31,32 Taken together, the development of broad Sap isoenzyme specific inhibitors is plausible and effective during different stages of infection, as well as lucrative. Sap-specific inhibition is also required to circumvent the involvement of endogenic proteinases. Future research for such inhibitors should, therefore, also include structure based inhibitor design methods, exploiting the unique S3 pocket considered to be a hallmark of the Sap-family,27 as a possible source of enzyme specificity and selectivity.

It is noted that the concentrations of the drugs required to reduce significantly adherence of C. albicans (of CBS 5982) to epithelial and endothelial cells are approximately 20-fold lower than those necessary to reduce Sap release of CBS 5982, indicating that predominantly non-Sap dependent adhesion is inhibited. This may be of importance for other Candida spp., which do not express Saps.33

In conclusion, Laccaridiones, in particular Laccaridione B, may represent a promising novel type of antimycotic drug, primarily targeting virulence factors such as adhesion, without killing the yeast.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Austrian ‘Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung’ (FWF P17043-B13) and the EU Network of Excellence Euro-PathoGenomics (LSHB-CT-2005-512061).

References

- 1.Odds FC, editor. Bailliere Tindall. 2nd edition. Oxford: Elsevier; 1998. Ecology of Candida and epidemiology of candidosis; pp. 68–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman DC, Sullivan DJ, Bennett DE, Moran GP, Barry HJ, Shanley DB. Candidiasis: the emergence of a novel species, Candida dubliniensis. AIDS. 1997;11:557–67. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odds FC, editor. Bailliere Tindall. 2nd edition. Oxford: Elsevier; 1998. Factors that predispose the host to candidosis; pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hube B, Sanglard D, Odds FC, et al. Disruption of each of the aspartyl proteinase genes SAP1, SAP2, and SAP3 of Candida albicans attenuates virulence. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3529–38. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3529-3538.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies DR. The structure and function of aspartic proteinases. Annu Rev Biophys Chem. 1990;19:189–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.001201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homma M, Kanbe T, Hiroji C, Tanak K. Detection of intracellular forms of secretory aspartic proteinase in Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;138:627–33. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staib F. Proteolysis and pathogenicity of Candida albicans strains. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1969;37:345–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02129881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staib F. Serum proteins as nitrogen source for yeast-like fungi. Sabouraudia. 1965;4:187–93. doi: 10.1080/00362176685190421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghannoum M, Abu-Elteen K. Correlative relationship between production, adherence, and pathogenicity of various strains of Candida albicans. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:407–13. doi: 10.1080/02681218680000621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaller M, Korting HC, Schäfer W, Bastert J, WenChieh C, Hube B. Secreted aspartic proteinase activity contributes to tissue damage in a model of human oral candidosis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:169–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminishi H, Miyaguchi H, Tamaki T, et al. Degradation of humoral host defense by Candida albicans proteinase. Infect Immun. 1995;63:984–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.984-988.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beausejour A, Grenier D, Goulet JP, Deslauriers N. Proteolytic activation of the interleukin-1β precursor by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:676–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.676-681.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Bernardis F, Arancia S, Moreli L, et al. Evidence that members of the secretory aspartyl proteinase gene family, in particular SAP2, are virulence factors for Candida vaginitis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:201–8. doi: 10.1086/314546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson RD, Shibata N, Podzorsky RP, Heron MJ. Candida mannan: chemistry, suppression, of cell mediated immunity, and possible mechanisms of action. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:1–19. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White TC, Agabian N. Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinases: isoenzyme pattern is petermined by cell type, and levels are determined by environmental factors. Am Soc Microbiol. 1995;177:5215–21. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5215-5221.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg A, Görls H, Dörfelt H, Walther G, Schlegel B, Gräfe U. Aureoquinone, a new protease inhibitor from Aureobasidium spp. J Antibiot. 2000;53:1293–5. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg A, Reiber K, Dörfelt H, Walther G, Schlegel B, Gräfe U. Laccaridiones A and B, new protease inhibitors from Laccaria amethystea. J Antibiot. 2000;53:1313–6. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pleyer L. Influence of novel bioactive substances on adhesion and protease release and activity of Candida. Dissertation; Austria: University of Innsbruck: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Würzner R, Langgartner M, Spötl L, et al. Temperature-dependent surface expression of the beta-2-integrin analogue of Candida albicans and its role in adhesion to the human endothelium. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1996;13:161–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagl M, Gruber A, Fuchs A, et al. Impact of N-chlorotaurine on viability and production of secreted aspartyl proteinases of Candida spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1996–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1996-1999.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson EK. Inhibition by Bestatin of a mouse ascites tumor dipeptidase. Reversal by certain substrates. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8004–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruber A, Lukasser-Vogl E, Borg-von Zepelin M, Dierich MP, Wurzner R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160 and gp41 binding to Candida albicans selectively enhances candidal virulence in vitro. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1057–63. doi: 10.1086/515231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ollert MW, Wende C, Gorlich M, et al. Increased expression of Candida albicans secretory proteinase, a putative virulence factor, in isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2543–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2543-2549.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassone A, De Bernardis F, Torosantucci A, Taconelli E, Tumbarello M, Cauda R. In vitro and in vivo activity of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:448–53. doi: 10.1086/314871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bektic J, Lell CP, Fuchs A, et al. HIV protease inhibitors attenuate adherence of Candida albicans to epithelial cells in vitro. Immunol Med Microbiol. 2001;31:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Rare and emerging opportunistic fungal pathogens: concern for resistance beyond Candida ablicans and Apergillus fumigatus. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4419–31. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4419-4431.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pranav Kumar SK, Kulkarni VM. Insights into the selective inhibition of Candida albicans secreted aspartyl protease: a docking analysis study. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;10:1153–70. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naglik JR, Rodgers CA, Shirlaw PJ, et al. Differential expression of Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase and phospholipase B genes in humans correlates with active oral and vaginal infections. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:469–79. doi: 10.1086/376536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ibrahim AS, Fille SG, Sanglard D, Edwards JE, Hube B. Secreted aspartyl proteinases and interactions of Candida albicans with human endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3003–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.3003-3005.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falkensammer B, Pilz G, Bektić J, Imwidthaya P, Jöhrer K, Speth C, Lass-Flörl C, Dierich MP, Würzner R. Absent reduction by HIV protease inhibitors of Candida albicans adhesion to endothelial cells. Mycoses. 2007;50:172–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald F. Secretion of inducible proteinase by pathogenic Candida species. Sabouraudia. 1984;22:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rüchel R, Böning B, Borg M. Characterization of a secreted proteinase of Candida parapsilosis and evidence for the absence of the enzyme during infection in vivo. Infect Immun. 1986;53:411–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.411-419.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pichova I, Pavlickova L, Dostal J, et al. Secreted aspartic proteases of Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis and Candida lusitaniae. Inhibition with peptidomimetic inhibitors. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2669–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]