Abstract

Pathogenic fungi represent a major threat particularly to immunocompromised hosts, leading to severe, and often lethal, systemic opportunistic infections. Although the impaired immune status of the host is clearly the most important factor leading to disease, virulence factors of the fungus also play a role. Factor H (FH) and its splice product FHL-1 represent the major fluid phase inhibitors of the alternative pathway of complement, whereas C4b-binding protein (C4bp) is the main fluid phase inhibitor of the classical and lectin pathways. Both proteins can bind to the surface of various human pathogens conveying resistance to complement destruction and thus contribute to their pathogenic potential. We have recently shown that Candida albicans evades complement by binding both Factor H and C4bp.

Here we show that moulds such as Aspergillus spp. bind Factor H, the splicing variant FHL-1 and also C4bp. Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry studies show that the binding of Factor H and C4bp to Aspergillus spp. appears to be even stronger than to Candida spp. and that different, albeit possibly nearby, binding moieties mediate this surface attachment.

Keywords: Aspergillus spp, Candida spp, Factor H (FH), C4b binding protein (C4bp), Evasion

1. Introduction

In the century of extensive iatrogenic immunosuppression (transplantation, tumour chemotherapy), Aspergillus spp. represents a major cause of severe and often lethal, systemic opportunistic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.

Invasive aspergillosis is the major infectious cause of death in leukaemia and stem cell transplantation; with Aspergillus fumigatus ranked first and Aspergillus terreus ranked third according to pathogenicity (Lass-Flörl et al., 2000). A. terreus is responsible for 80–100% of deaths caused by invasive aspergillosis, higher than for any of the other 20 pathogenic Aspergillus species. Furthermore, A. terreus is completely resistant to the powerful antimycotic agent amphotericin B (Johnson et al., 2000). As other supportive care has improved and most bacterial infections can be successfully treated, the importance of aspergillosis has increased, as it is now a major and direct or contributory cause of death in immunocompromised hosts.

Most pathogens invading the human body are attacked by the host immune system directly following entry and usually during further stages of infection. Host defence against fungi depends on phagocytosis, where complement plays a supportive role (Speth et al., 2004). Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) require complement for maximal chemotaxis, phagocytosis and fungicidal activity. Deposition of C3b on the surface of many invasive pathogens is essential for phagocytic host defence and complement mediated cell lysis (Walport, 2001a,b).

However, several pathogenic micro-organisms have developed specific strategies, including both biochemical or biophysical measures to resist C3b deposition, opsonophagocytosis or complement-mediated cytolytic damage, in order to evade complement and other human immune defence mechanisms. These measures increase the likelihood of microorganism survival in a hostile environment (Würzner, 1999). The adsorption of host-derived fluid phase complement inhibitors, such as Factor H (FH), factor-H-like protein 1 (FHL-1) or C4b-binding protein (C4bp) inhibits complement activation and has been reported for several micro-organisms (Kraiczy and Würzner, 2006; Würzner and Zipfel, 2004). Employment of these major inhibitors of the alternative and the classical C3 convertase by pathogens results in down-regulation or termination of complement activation (Rooijakkers and Strijp, 2007).

Factor H, FHL-1 and C4bp, similar to other regulators of complement activation (RCA) proteins, are built soley from complement control protein (CCP) modules, also termed short consensus repeats (SCRs). The alternative pathway inhibitor FH consists of 20 SCRs. FHL-1 is composed of 7 SCRs, which are identical to the N-terminal SCRs of Factor H, however with an additional unique C-terminal extension of four amino acids (Zipfel and Skerka, 1999). C4bp, the major inhibitor of the classical and lectin pathways, is the only circulating complement inhibitor with a polymeric structure, the molecule being composed of 6–8 identical α-chains and a single unique β-chain, the α- and β-chains being composed of eight and three short consensus repeats domains, respectively (Blom et al., 2004).

Recently, binding and acquisition of FH, FHL-1 and C4bp was shown for C. albicans (Meri et al., 2002,2004). Importantly, these proteins maintain their complement regulatory functions in their bound configuration, resulting in down-regulation or termination of the complement cascade (Meri et al., 2002,2004).

The present study evaluates complement evasion by moulds such as A. fumigatus and A. terreus, both of which, besides C. albicans, are major causes of severe, systemic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts.

2. Methods

2.1. Strains and growth conditions

Culture collection strains of C. albicans (SC5314 and CBS 5982), C. dubliniensis (CD38, D. Coleman, Dublin, Ireland, (Sullivan and Coleman, 1998; Gilfillan et al., 1998)) or Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Deutsche Stammsammlung für Mikroorganismen, Braunschweig, Germany (DSM) 70451) were grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar (1% peptone (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany),4% glucose (AppliChem, Neudorf, Austria)) and transferred to RPMI medium (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Vienna, Austria) for 16 h at 30 °C (predominantly yeasts present) or 37 °C (mostly hyphae present, only for Candida) for immunofluorescence (IF).

For fluorescence-activated cell analyses (FACS), colonies were washed off with FACS buffer from Sabouraud dextrose agar culture plates, previously grown at 37 °C for two days, fitrated through a 40 μm Nylon cell strainer (Becton Dickinson) and stored at 4 °C.

Culture collection strains of A. fumigatus, A. terreus, A. niger and A. nidulans (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD (ATCC) 204305, DSM 826, ATCC 9142 and ATCC 38163, respectively) were used for all experiments. Cultures were obtained from Sabouraud dextrose agar, either washed off with phosphate-buffered saline (for IF) or washed off with FACS buffer.

2.2. Plasma, antibodies, and proteins

Plasma was obtained from healthy human donors; EDTA was added at a concentration of 10 mM.

Factor H was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). FHL-1, FH SCRs 8–20 (Zipfel et al., 1994) and both the complete form of C4bp and a construct without β-chain and the attached protein S were generated or purified as described (Blom et al., 2001,2004).

A polyclonal rabbit antiserum raised against FH SCRs 1–4 antiserum for the detection of the N-terminal SCRs of Factor H and FHL-1 and a polyclonal rabbit IgG for the detection of the C-terminal SCRs 19–20 of Factor H (Zipfel et al., 1994) were used for detection of Factor H constructs in both IF and FACS. A polyclonal goat antiserum raised against human Factor H antiserum was obtained from Quidel (San Diego, CA).

The monoclonal mouse antibody 104 recognizing SCR1 of the C4bp α-chain (Berggard et al., 2001a) and a polyclonal rabbit antibody (ab9008) (Kask et al., 2002) were used for detection of C4bp.

Rabbit IgG, goat IgG and mouse IgG (obtained from the Department of Immunology, University of Göttingen) were used as control.

FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse, swine anti-rabbit and rabbit anti-goat antisera were purchased from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark).

2.3. Indirect immunofluorescence (IF)

Fungal hyphae were incubated with human EDTA-plasma (50%), C4bp or C4bp construct without ß-chain (both 20 μg/ml) for 4 h at 4 °C, followed by three washing steps using ice-cold PBS. Cells were incubated on slides coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30 min. After fixation (3 min in acetone/methanol) and blocking (15 min, 1% PBS-FCS) at room temperature, primary antibodies were incubated for 1 h (goat anti-Factor H 1:50; rabbit anti-FH SCRs 1–4, rabbit anti-FH SCRs 19–20 or rabbit anti-C4bp, all 20 μg/ml; controls goat IgG or rabbit IgG, both 20 μg/ml). Detection was performed via secondary FITC-labelled antibodies at a 1:40 dilution. Cells were counterstained with EvansBlue® (Sigma–Aldrich) and covered for immunofluorescence with Mowiol (Sigma–Aldrich). Analyses were done immediately thereafter.

2.4. Flow cytometry

Conidia (from Aspergillus spp.) or yeast cells (from Candida spp.) were incubated at 2 × 106 ml−1 (final concentration) with human EDTA-plasma (50%), Factor H, FHL-1, FH SCRs 8–20 or C4bp or the C4bp construct lacking the ß-chain (all 20 μg/ml) for 2 h at 4 °C. After two washing steps with ice-cold PBS, cells were blocked with 1% PBS-skim milk for 30 min, followed by incubation with the primary antibodies (goat anti-Factor H 1:50, rabbit anti-FH SCRs 1–4, rabbit anti-FH SCRs 19–20, rabbit anti-C4bp, or mouse monoclonal anti-C4bp, all 20 μg/ml) or controls goat IgG, rabbit IgG, or mouse IgG, all 20 μg/ml, diluted in washing buffer (WB: PBS supplemented with 1% BSA and 0.1% azide) for 2 h at 4 °C. After two washing steps with ice-cold PBS the secondary FITC-labelled antibodies were added at a dilution of 1:40 for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with WB and then fixed in PBS supplemented with 1% formalin and 0.1% azide. All steps were performed at 4 °C. Labelled cells were examined by FACS (Becton Dickinson), forward and sideward scatters were used to define the fluorescent cell population and 10,000 events were routinely counted.

3. Results

3.1. Factor H binding to Aspergillus spp

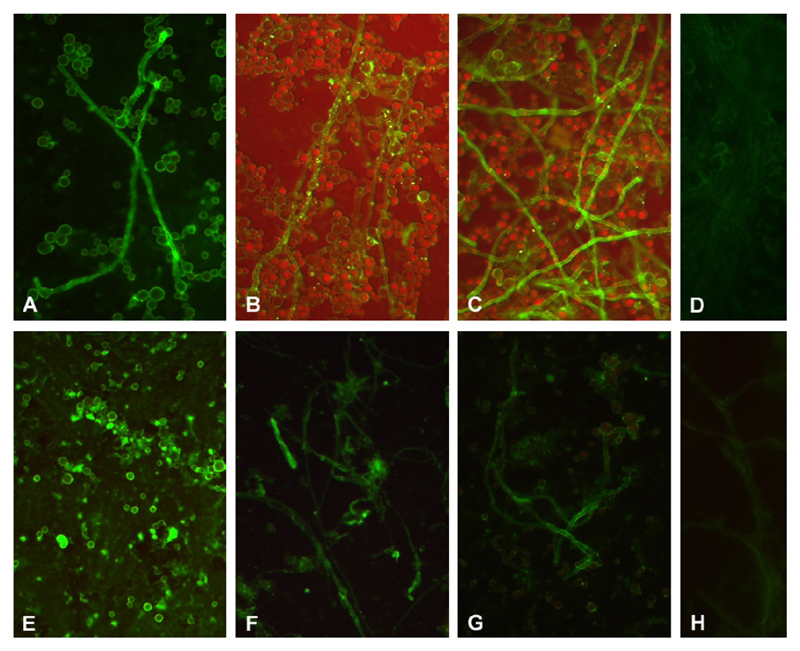

Strong binding of Factor H to hyphae of A. fumigatus and A. terreus was detected by immunofluorescence following incubation in EDTA plasma, as staining with Factor H antiserum was marked (Fig. 1A and E). This binding was confirmed by using antiserum or purified IgG directed against SCRs 1–4 (common for FH and FHL-1) or against SCRs 19–20 (unique for FH) (Fig. 1B, C, F and G, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence analyses of Factor H (FH) binding to Aspergillus species. A. fumigatus (A–D) and A. terreus (E–H). Interactions were shown for Factor H and FHL-1 from plasma using antiserum specific for Factor H (A and E), Factor H/FHL-1 SCRs 1–4 (B and F) and C-terminal Factor H SCRs 19–20 (C and G). D, H: plasma, followed by goat IgG control. The results obtained after staining with rabbit IgG, instead of anti-FH SCRs 1–4 or anti-FH SCRs 19–20 were similar to the control (not shown). Representative examples of quadruplicates experiments are shown.

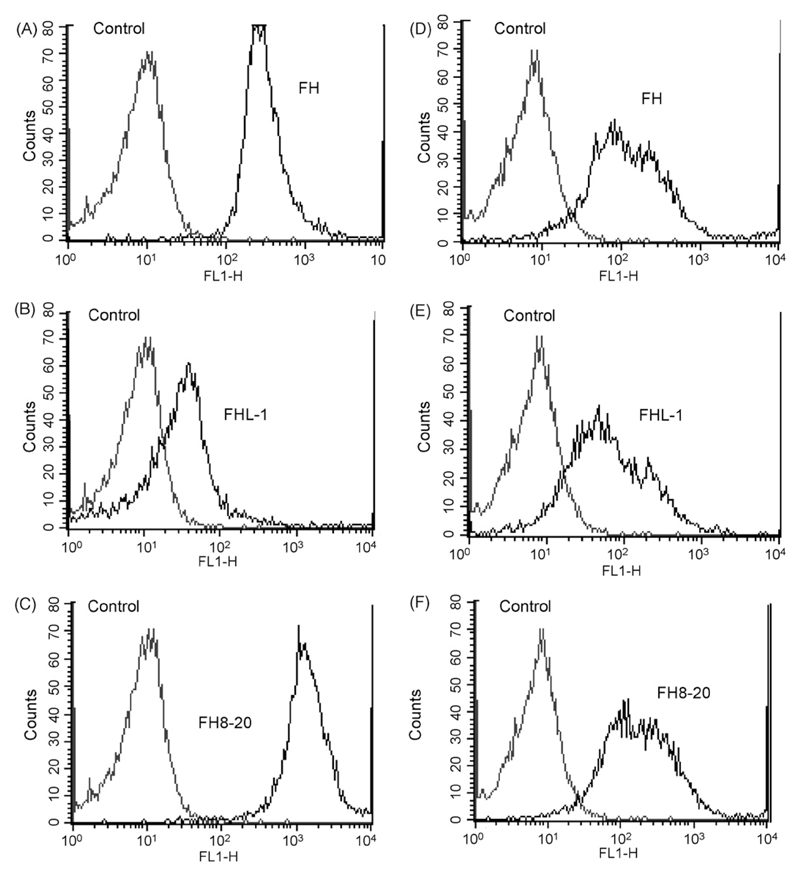

Binding of Factor H was confirmed by flow cytometry, using homogeneous cell populations by filtration of cell suspensions of A. fumigatus and A. terreus (Fig. 2). Interestingly, A. nidulans and A. niger also bound Factor H (not shown). Binding of intact Factor H, FHL-1 and deletion fragment Factor H SCRs 8–20 to A. fumigatus was confirmed with polyclonal anti-FH, anti-FH-SCRs 1–4 and anti-FH-SCRs 19–20, respectively (Fig. 2A–C). The binding patterns were comparable for A. terreus (Fig. 2D–F).

Fig. 2.

Determination of Factor H (FH) binding to the surface of A. fumigatus (A–C) and A. terreus by flow cytometry (D–F). Conidia were incubated with Factor H (A and D), FHL-1 (B and E) or Factor H SCRs 8–20 (C and F). Bound regulators were detected with the specific Factor H antisera. Cells incubated in buffer only were used as control. The results obtained after staining with goat IgG or rabbit IgG, instead of anti-Factor H antiserum or anti-FH SCRs 1–4 or anti-FH SCRs 19–20, respectively, were similar to the buffer control (not shown). Representative examples of quadruplicates experiments are shown.

3.2. C4bp binding to Aspergillus spp

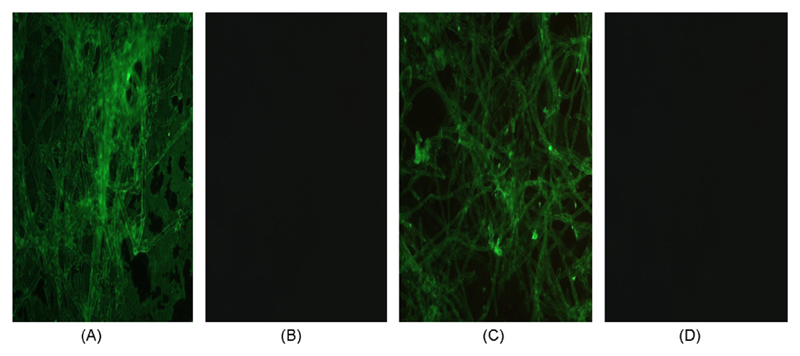

Immunofluorescence studies, using a polyclonal rabbit anti-C4bp or a monoclonal mouse anti-C4bp monoclonal antibody (data not shown), revealed that C4bp binds to the surface of A. fumigatus and A. terreus (Fig. 3) and staining of these antibodies appeared to be slightly stronger in the case of A. fumigatus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence analyses of C4bp binding to A. fumigatus (A) and A. terreus (C), as detected by using C4bp followed by polyclonal anti-C4bp. (B and D): C4bp, followed by rabbit IgG control. The binding patterns were identical when the C4bp construct without β-chain was used for both antibodies (not shown). Representative examples of quadruplicates experiments are shown.

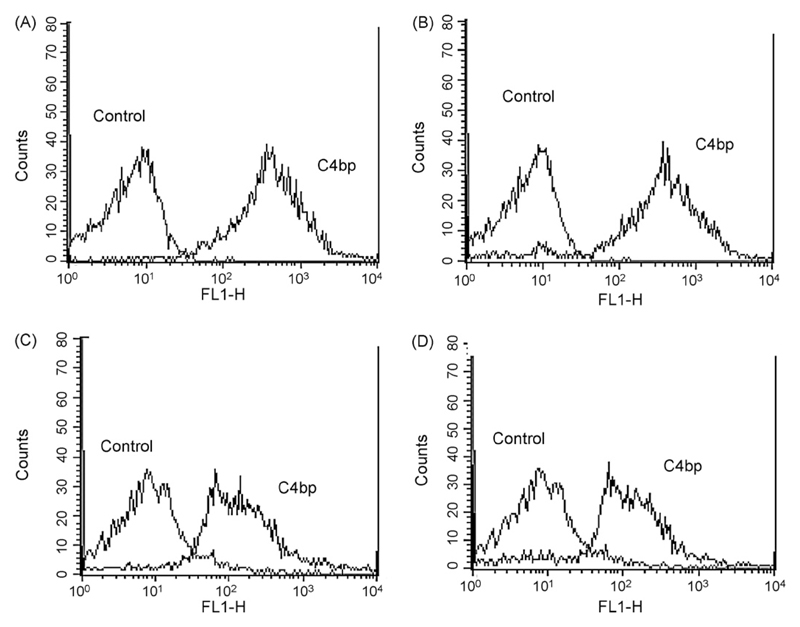

This result was confirmed by flow cytometry using monoclonal (Fig. 4) or polyclonal antibodies (not shown). When the C4bp construct devoid of ß-chain was used, binding was detected, again using either monoclonal (Fig. 4) or polyclonal IgG (data not shown). Interestingly, binding of C4bp was also detected for A. nidulans and A. niger (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Determination by flow cytometry of C4bp surface bound to A. fumigatus (A and C) and A. terreus (B and D). Conidia were incubated with C4bp and monoclonal IgG (A and B) or the C4bp construct without β-chain and the monoclonal anti-C4bp (C and D). The binding patterns were identical when the polyclonal anti-C4bp IgG was used for detection (not shown). Cells incubated in buffer instead of C4bp or its construct was used as control. The application of mouse IgG or rabbit IgG was comparable to the control (not shown). Representative examples of quadruplicates experiments are shown.

3.3. Evaluation of a possible interference of Factor H binding with subsequent C4bp binding and vice versa

When A. fumigatus (Fig. 5A) or A. terreus (data not shown) were preincubated with FHL-1 prior to C4bp application (both at the same concentrations as used in the previous experiments, 20 μg/ml), no decrease in immunofluorescence signal was observed (Fig. 5B), which, however, was observed when Factor H was used in preincubation prior to addition of C4bp (both at 20 μg/ml; Fig. 5C). FHL-1 or FH binding (Fig. 5D and F) was not found blocked by preincubation with C4bp (Fig. 5E and G). A potential cross-reactivity of the antibodies used was ruled out as control experiments, in which the moulds were preincubated with C4bp prior to incubation with anti-FH, or preincubated with Factor H prior to incubation with anti-C4bp (all at the same concentrations as used in the previous experiments), yielded negative results.

Fig. 5.

Interference of C4bp binding to A. fumigatus (A) after preabsorption with FHL-1 (B) or Factor H (FH) (C) and influence of FHL-1 or Factor H binding to A. fumigatus (D and F) after preabsorption with C4bp (E and G). Determination by polyclonal anti-C4bp (A–C) or polyclonal anti-Factor H (D–G). Cells incubated in buffer were used as control. Representative examples of quadruplicates experiments are shown.

3.4. Comparison of Factor H and C4bp binding to Aspergillus spp. and Candida spp

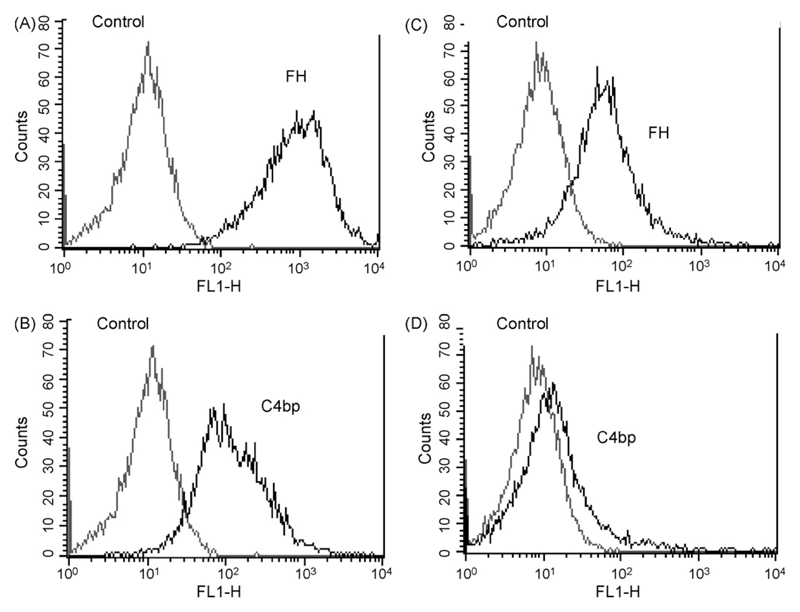

Binding of both Factor H and C4bp, not only to C. albicans (CBS 5982 and SC5314), but also to C. dubliniensis was clearly detected by immunofluorescence; binding of C4bp was verified using both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies (data not shown). Flow cytometry confirmed these data and showed that both Factor H and C4bp binding was stronger to Aspergillus spp. when compared to Candida spp. (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Evaluation of Factor H (A and C) or C4bp (B and D) binding to A. fumigatus (A and B) in comparison to C. albicans (C and D). Determination by polyclonal anti-Factor H (A and C) or polyclonal anti-C4bp (B and D). Cells incubated in buffer were used as control. Representative examples of quadruplicates experiments are shown.

4. Discussion

Complement evasion by acquiring soluble complement inhibitors from the host is a successful immune evasion strategy and allows pathogens to overcome the destructive action of this powerful innate immune system. This strategy is applied by many types of invaders, including viruses, bacteria, parasites (Würzner and Zipfel, 2004) and yeasts (Meri et al., 2002,2004).

Factor H, the main inhibitor of the alternative pathway, and its splicing product factor-H-like protein-1 (FHL-1) are utilized by numerous pathogens for their protection against complement destruction, when establishing infection in the host (Kraiczy and Würzner, 2006). Recently identified examples of Factor H acquiring pathogens include the periodontal Treponema denticola (McDowell et al., 2007) and West Nile virus (Chung et al., 2006). In this study investigating Factor H and C4bp binding to moulds, we also extend the studies on Candida spp. acquiring Factor H to C. dubliniensis, which according to phenotypic and morphological features (Staib et al., 2000) is closely related to C. albicans, as it can also bind Factor H, FHL-1 and the construct involving SCRs 8–20 (data not shown).

However, not only yeasts, but also the medically equally important moulds, such as A. fumigatus and A. terreus bind Factor H, as shown here by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry analyses. This was confirmed by using antibodies against SCRs 1–4 (detecting common epitopes of Factor H and FHL-1) and SCRs 19–20 (epitopes unique for Factor H and a construct involving SCRs 8–20). The use of FHL-1 and the recombinant construct SCRs 8–20 revealed the presence of two different binding moieties on A. fumigatus and A. terreus, one mediating attachment for the N-terminal region (binding to Factor H and its splicing product FHL-1) and one for the C-terminal region, as is also the case for C. albicans (Meri et al., 2002). These binding regions are presumably located within SCRs 6–7 and 19–20, as shown for Candida (Meri et al., 2002) and other micro-organisms (Zipfel et al., 2002). On binding Factor H (or its splicing product FHL-1), it is postulated that the very N-terminally located complement inhibitory regions (SCRs 1–4) of the moulds would be pointing to the outside, thus allowing retention of their functional activity and complement evasion.

C4b-binding protein (C4bp), the main inhibitor of the classical and lectin pathways, can also be acquired on the surface of a number of human pathogens and thereby provide them resistance to complement and contribute to their pathogenic potential (Würzner and Zipfel, 2004). C4bp binding to Borrelia recurrentis and B. duttonii represents a recently published example (Meri et al., 2006). In addition, we have previously shown that both yeast and hyphal forms of C. albicans capture C4bp on their surfaces (Meri et al., 2004). This leads to down-regulation of complement and confers enhanced adhesion (Meri et al., 2004). We have now extended this finding to C. dubliniensis, which also showed binding of C4bp (data not shown).

Both A. fumigatus and A. terreus strongly bound C4bp and it can be concluded that the ß-chain is not involved in binding. Binding of C4bp not only to C. albicans (Meri et al., 2004), but also to bacteria, such as Bordetella pertussis (Berggard et al., 2001b) or Streptococcus pyogenes (Berggard et al., 2001a; Jenkins et al., 2006), is mediated by SCRs 1–2 of C4bp α-chain. In contrast, Escherichia coli binds to SCR3 of C4bp, conferring serum resistance (Prasadarao et al., 2002).

The fact that both A. fumigatus and A. terreus strongly bind both inhibitors makes it very likely that this acquisition represents a general complement evasion mechanism executed by pathogenic moulds. It is not entirely surprising that “apathogenic” moulds, such as A. nidulans, also bind Factor H (data not shown) or C4bp (Meri et al., 2004) as was observed for the “apathogenic” yeast S. cerevisiae (binding Factor H, data not shown; binding C4bp, Meri et al., 2004). This may be indicative of these molecules having arisen early in evolution as an important prerequisite for these opportunistic invaders to survive in the host. Subsequently, not all members of Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. then developed into a human pathogen. Alternatively, A. fumigatus and A. terreus are prevalent in the environment, whereas A. nidulans or A. niger are rarely found. This may also explain why the latter are considered “apathogenic”.

Competition assays indicated that FHL-1, but not Factor H, competes with C4bp for binding on the yeast surface (Meri et al., 2002). Thus, it appears that two binding moieties are involved, one for binding C4bp or FHL-1 and the other for binding fulllength Factor H (Meri et al., 2002). In the case of Aspergillus, a different picture was observed. The presence of C4bp does not inhibit binding of FHL-1 or Factor H. However, Factor H is able to partially block binding of C4bp. This may be due to steric hindrance and not necessarily due to competition with the same ligand.

Interestingly, our investigations also showed, by both immunofluorescence and FACS, that binding of both Factor H and C4bp to Aspergillus spp. appears to be stronger than to Candida spp., which may imply that such an evasion molecule is more abundant on, and possibly more important for, Aspergillus spp.

Further support of complement evasion being crucial for Aspergillus comes from earlier reports demonstrating that Aspergillus produces a soluble extracellular inhibitor (Washburn et al., 1986; Washburn et al., 1990), which is, however, not present on apathogenic Aspergillus spp. (Washburn et al., 1990). It is therefore unlikely to be identical to the Factor H binding molecule, as that is detected on A. nidulans and A. niger. In addition, other molecules such as Arp1, an enzyme similar to scytalone, and Alb1, which is required for conidial pigmentation, both prevent increased C3 binding (Tsai et al., 1997; Tsai et al., 1998). It would be interesting to obtain arp −/− and alb −/− deletion mutants in order to clarify whether or not the Factor H molecule is related to that/these evasion procedure(s).

Several complement receptor-like proteins have been described for Candida (Meri et al., 2002; Speth et al., 2004), including CR3-like analogues (Heidenreich and Dierich, 1985; Gale et al., 1998), also emphasizing the importance of complement evasion for survival in the host. One of these analogues has been shown to be important for fungal virulence, as it is involved in adhesion and filamentous growth (Gale et al., 1998).

A different CR3-like analogue has been found to bind to HIV (Würzner et al., 1997), which subsequently induces an increase in fungal virulence (Gruber et al., 1998), including enhanced adhesion.

The human CR3 receptor (CD11b/CD18, αMß2) represents a receptor for Factor H (DiScipio et al., 1998) and can also act as an adhesion ligand. Interestingly, such a CR3-analogue has also been described for Aspergillus spp. (Delavar, 2004). Based on these findings, it is tempting to speculate that the Factor H/FHL-1-binding molecule(s) described here actually represent(s) a CR3-like ligand, as was speculated for the Candida Factor H binding molecule (Meri et al., 2002). Molecular characterisation will eventually shed more light on the nature of these binding moieties.

Identifying such receptors – also as putative targets for therapy – may, in particular, be beneficial for treating fungal infections as, unlike in the case of bacterial infection, therapy does not usually lead to a cure of the disease. Finding other specific targets for intervention may be of great advantage as, despite expensive antimycotic therapy, the mortality is still extremely high.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The project “Fungal complement Factor H receptor and virulence” was supported by the FWF Grant No. P17043, and the EU-Projects QLG1–CT2001–01039 and LSHB-CT-2005-512061. A. nidulans was kindly provided by Dr. F. Marx and Dr. H. Haas, Biocenter, IMU, Innsbruck. We acknowledge the help of R. Colonia.

References

- Berggard K, Johnsson E, Morfeldt E, Persson J, Stalhammar-Carlemalm M, Lindahl G. Binding of human C4BP to the hypervariable region of M protein: a molecular mechanism of phagocytosis resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes. Microbiol Mol. 2001a;42:539–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggard K, Lindahl G, Dahlback B, Blom AM. Bordetella pertussis binds to human C4b-binding protein (C4BP) at a site similar to that used by the natural ligand C4b. Eur J Immunol. 2001b;31:2771–2780. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200109)31:9<2771::aid-immu2771>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom AM, Kask L, Dahlbäck B. Structural requirement for the complement regulatory activities of C4b-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27136–27144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom AM, Villoutreix BO, Dahlback B. Complement inhibitor C4b-binding protein-friend or foe in the innate immune system? Mol Immunol. 2004;40:1333–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KM, Liszewski MK, Nybakken G, Davis AE, Townsend RR, Fremont DH, Atkinson JP, Diamond MS. West Nile virus nonstructural protein NS1 inhibits complement activation by binding the regulatory protein factor H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19111–19116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605668103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delavar A. Characterisation of the CR3-analogue on Aspergillus spp. Diploma thesis, University of Innsbruck; Austria: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DiScipio RG, Daffern PJ, Schraufstatter IU, Sriramarao P. Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes adhere to complement factor H through an interaction that involves alphaMbeta2 (CD11b/CD18) J Immunol. 1998;160:4057–4066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale CA, Bendel CM, McClellan M, Hauser M, Becker JM, Berman J, Hostetter MK. Linkage of adhesion, filamentous growth, and virulence in Candida albicans to a single gene, INT1. Science. 1998;279:1355–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilfillan GD, Sullivan DJ, Haynes K, Parkinson T, Coleman DC, Gow NA. Candida dubliniensis: phylogeny and putative virulence factors. Microbiology. 1998;144:829–838. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A, Lukasser-Vogl E, Borg von Zepelin M, Dierich MP, Würzner R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160/gp41 binding to Candida albicans selectively enhances candidal virulence in vitro. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1057–1063. doi: 10.1086/515231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich F, Dierich MP. Candida albicans and Candida stellatoidea, in contrast to other Candida species, bind iC3b and C3d but not C3b. Infect Immun. 1985;50:598–600. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.598-600.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins HT, Mark L, Ball G, Persson J, Lindahl G, Uhrin D, Blom AM, Barlow PN. Human C4b-binding protein, structural basis for interaction with streptococcal M protein, a major bacterial virulence factor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3690–3697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EM, Oakley KL, Radford SA, Moore CB, Warn P, Warnock DW, Denning DW. Lack of correlation of in vitro amphotericin B susceptibility testing with outcome in a murine model of Aspergillus infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:85–93. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kask L, Hillarp A, Ramesh B, Dahlbäck B, Blom A. Structural requirements for the intra-cellular subunit polymerization of the complement inhibitor C4b-binding protein. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9349–9357. doi: 10.1021/bi025980+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Würzner R. Complement escape of human pathogenic bacteria by acquisition of complement regulators. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass-Flörl C, Rath PM, Niederwieser D, Kofler G, Würzner R, Kreczy A, Dierich MP. Aspergillus terreus infections in haematological malignancies: molecular epidemiology suggests association with in-hospital plants. J Hosp Infect. 2000;46:31–35. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Frederick J, Stamm L, Marconi RT. Identification of the gene encoding the FhbB protein of Treponema denticola, a highly unique factor H-like protein 1 binding protein. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1050–1054. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01458-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meri T, Hartmann A, Lenk D, Eck R, Würzner R, Hellwage J, Meri S, Zipfel PF. The yeast Candida albicans binds complement regulators factor H and FHL-1. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5185–5192. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5185-5192.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meri T, Blom AM, Hartmann A, Lenk D, Meri S, Zipfel PF. The hyphal and yeast forms of Candida albicans bind the complement regulator C4b-binding protein. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6633–6641. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6633-6641.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meri T, Cutler SJ, Blom AM, Meri S, Jokiranta TS. Relapsing fever spirochetes Borrelia recurrentis and B. duttonii acquire complement regulators C4b-binding protein and factor H. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4157–4163. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00007-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasadarao NV, Blom AM, Villoutreix BO, Linsangan LC. A novel interaction of outer membrane protein A with C4b binding protein mediates serum resistance of Escherichia coli K1. J Immunol. 2002;169:6352–6360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooijakkers SHM, Strijp JAG. Bacterial complement evasion. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speth C, Rambach G, Lass-Flörl C, Dierich MP, Würzner R. The role of complement in invasive fungal infections. Mycoses. 2004;47:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staib P, Michel S, Kohler G, Morschhauser J. A molecular genetic system for the pathogenic yeast Candida dubliniensis. Gene. 2000;242:393–398. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D, Coleman D. Candida dubliniensis: characteristics and identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:329–334. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.329-334.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HF, Washburn RG, Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ. Aspergillus fumigatus arp1 modulates conidial pigmentation and complement deposition. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:175–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5681921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HF, Chang YC, Washburn RG, Wheeler MH, Kwon-Chung KJ. The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3031–3038. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3031-3038.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport MJ. Complement. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001a;344:1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport MJ. Complement. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001b;344:1140–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RG, Hammer CH, Bennett JE. Inhibition of complement by culture supernatants of Aspergillus fumigatus. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:944–951. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.6.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RG, DeHart DJ, Agwu DE, Bryant-Varela BJ, Julian NC. Aspergillus fumigatus complement inhibitor: production, characterization, and purification by hydrophobic interaction and thin-layer chromatography. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3508–3515. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3508-3515.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würzner R, Gruber A, Stoiber H, Spruth M, Chen YH, Lukasser-Vogl E, Schwendinger M, Dierich MP. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 binds to Candida albicans via complement C3-like regions. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:492–498. doi: 10.1086/514069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würzner R. Evasion of pathogens by avoiding recognition or eradication by complement, in part via molecular mimicry. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würzner R, Zipfel PF. Microbial evasion mechanisms against human complement. In: Szebeni J, editor. Complement. Kluwer; Dordrecht: 2004. pp. 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Jokiranta TS, Hellwage J, Koistinen V, Meri S. The factor H protein family. Immunopharmacology. 1994;42:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Skerka C. FHL-1/reconectin: a human complement and immune regulator with cell-adhesive function. Immunol Today. 1999;20:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Skerka C, Hellwage J, Jokiranta TS, Meri S, Brade V, Kraiczy P, Noris M, Remuzzi G. Factor H family proteins: on complement, microbes and human diseases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:971–978. doi: 10.1042/bst0300971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.