Abstract

BACKGROUND

Breastfeeding is associated with numerous health benefits for the infant and mother. Latina women in the U.S. have historically had high overall rates of initiation and duration of breastfeeding. However, these rates vary by nativity and time lived in the U.S. Exclusive breastfeeding patterns among Latina women are unclear. In this study we investigate the current and exclusive breastfeeding patterns of Mexican-origin women at four time points from delivery to 10 months postpartum to determine the combined association of nativity and country of education with breastfeeding duration and supplementation.

METHODS

Data are from the Postpartum Contraception Study, a prospective cohort study of postpartum women ages 18–44 recruited from three hospitals in Austin and El Paso, TX. We included Mexican-origin women who were born in either the U.S. or Mexico in the analytic sample (n=593).

RESULTS

Women completing schooling in Mexico had higher rates of overall breastfeeding throughout the study period than women educated in the U.S., regardless of country of birth. This trend held in multivariate models while diminishing over time. Women born in Mexico who completed their schooling in the U.S. were least likely to exclusively breastfeed.

DISCUSSION

Country of education should also be considered when assessing Latina women’s risk for breastfeeding discontinuation. Efforts should be made to identify the barriers and facilitators to breastfeeding among U.S.-educated Mexican-origin women to enhance existing breastfeeding promotion efforts in the U.S.

Keywords: breastfeeding duration, exclusive breastfeeding, Latina, Hispanic, Mexican-origin

INTRODUCTION

Women of Mexican origin are one of the largest and fastest growing minority populations in the U.S. (1,2). Further, the demographic characteristics of this population have changed in recent years due to slowing immigration, resulting in an increasing percentage of Mexican-origin women born in the U.S. (3). In previous decades, the number of immigrants from Mexico was equal to or exceeded the number of Mexican-origin individuals born in the U.S. Conversely, from 2000 to 2010, the number of U.S.-born births of Mexican origin was 1.7 times the number of new immigrants from Mexico (4). This changing demographic profile suggests the sociocultural influences of Mexican-origin women’s health behaviors, including breastfeeding, may be changing, as well.

There is a dearth of information available noting the differences in U.S. Hispanic/Latina women’s breastfeeding patterns by country of origin (5). However, as a population, Latina women in the United States have historically had high breastfeeding rates. These rates vary by nativity, years lived in the U.S., and characteristics that have sometimes been labeled as indicators of acculturation, with women with stronger ties to their country of origin demonstrating higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration (6–9). While such associations with Latina women’s breastfeeding intentions, initiation, and duration have been well-documented, the evidence is mixed regarding whether Latina women with stronger ties to their Latin American country of origin exclusively breastfeed more often and for longer durations (8,10–12) or if they are at elevated risk for very early supplementation—a phenomenon known as “los dos” (13–15). Further, there are unanswered questions as to whether the differences in breastfeeding patterns among Latina women derive from ingrained breastfeeding ideals and norms, or from maternal behaviors and contexts, such as smoking and labor force participation, that are known to influence breastfeeding in the entire U.S. population (16,17).

Acculturation is commonly assessed in the literature as a predictor of U.S. Latina women’s health behaviors and outcomes. However, many are critical of the concept and measurement of acculturation as a valid representation of an individual’s attributes or experiences (18–21). Specifically, critics are concerned with the assumptions made about the concept of acculturation, such as that two distinct cultures are involved, and that acculturation is a process of change that individuals move through due to exposure to a host culture (18,20). Further, there are concerns with the wide variation in how acculturation is conceptualized and measured in research of individuals’ health behaviors and outcomes (20). In studying the relationship of acculturation with Latina women’s breastfeeding behaviors in the U.S., some represent acculturation with Spanish or English language preference (7,11,12), others with multidimensional scales of the frequency and enjoyment of activities (e.g., reading, writing, speaking, and thinking) in Spanish or English (22), others with multidimensional scales including measurements of attitudes about gender roles and cultural engagement (23), and still others with combinations of measures (5,24,25) such as a combination of nativity, generation, time lived in the U.S., and language use.

Acknowledging the critiques of acculturation, we instead consider U.S. Latina women’s background characteristics—specifically where each woman was born and where she completed her most recent year of schooling—to represent the environmental context she experienced during salient social and behavioral formative periods of her life: early life and the school years. Health researchers have previously employed similar measures such as women’s nativity and time in the U.S. However, using the number of years a woman has lived in the U.S. may mean something very different for two women who have lived in the U.S. for 10 years if one woman migrated at age 20 and the other, age 40. Part of this difference may be due to where each of the women experienced sensitive developmental periods when many of the values and behaviors of adulthood begin, and are shaped (26–28). Numerous contextual influences of social and behavioral development (e.g., peers, nonfamilial adults, neighborhood, and educational policy) are experienced in the school environment (29). Further, it is likely that self-reporting an individual’s country of schooling is more robust to recall bias than reporting where one lived during specific ages in youth. Thus, in the current study, we consider where women were born (Mexico or U.S.) and completed their most recent year of schooling (Mexico or U.S.) to represent women’s environmental context during social and behavioral formative years. Women’s most recent year of schooling ranged from elementary school to college in our sample. In earlier work with oral contraceptive users in El Paso, this combination of nativity and location of schooling was found to be a strong predictor of cross-border procurement of oral contraception (30).

In addition to relying on controversial measures of acculturation, the literature assessing the influence of U.S. Latina mothers’ country of origin on breastfeeding behaviors to date is limited in other ways. Research in this field tends to focus solely on breastfeeding intentions or initiation (5,9,11,24,31–33). If breastfeeding duration is assessed, it is often for short periods (up to 10 weeks) (12,22), is retrospective in assessment (24,34), or does not consider whether women are breastfeeding exclusively or supplementing (6,23,35). Most notable, studies frequently combine women from multiple countries of origin despite the vast cultural differences and health behavior practices among women from different Latin American countries (36).

The current study aims to address these gaps by assessing whether a measure of contextual influences experienced during social and behavioral formative years (country of birth and schooling) predicts Mexican-origin women’s exclusive breastfeeding at 3-months postpartum and duration of breastfeeding at four time points in the first 10 months postpartum.

METHODS

Data Source and Analytic Variables

Data are from the Postpartum Contraception Study. This study was a prospective cohort study of 800 postpartum women recruited from three hospitals in Austin and El Paso, TX in 2012. All three hospitals have breastfeeding promotion programs with bilingual staff providing breastfeeding support and education while women are in the hospital after delivery. Women ages 18–44 who wanted to delay childbearing for at least 24 months were eligible for the original study. Participants completed structured interviews with bilingual interviewers following delivery and at 3, 7, and 10 months postpartum. Baseline interviews were conducted in-person at the participants’ hospitals of delivery prior to discharge after giving birth. Interviews at 3, 7, and 10 months postpartum were conducted by telephone. More details of the study procedures can be found elsewhere (37). For the current study, we included Mexican-origin women who were born in either the U.S. or Mexico in the analytic sample (n=593).

Participants reported whether they were currently breastfeeding at delivery, 3, 7, and 10 months postpartum. To determine exclusive breastfeeding behaviors, at 3 months postpartum, currently breastfeeding mothers were asked if they had ever given their child anything besides breast milk.

During the interview following delivery, women reported their country of birth and in which country they completed their most recent year of education—the U.S., Mexico, or Other. In the questionnaire, prior to asking the highest degree or level of school that participants have completed, they are asked “In what country did you complete your last year of schooling?” We excluded women reporting “Other” countries of birth besides the U.S. and Mexico from analyses (n=21). We created three categories: 1) born in the U.S. and completed education in the U.S. (US-US), 2) born in Mexico and completed education in the U.S. (MX-US), and 3) born in Mexico and completed education in Mexico (MX-MX). Seventeen participants were born in the U.S. and completed their education in Mexico. We included these participants with those born in Mexico and completing their education in Mexico per prior research with this measure (24).

We chose potential covariates for multivariate models based on prior research noting their associations with women’s breastfeeding practices (6,15,38–40). We considered both stable, time-constant covariates—factors assessed at one time point during the study—as well as time-changing covariates—situational factors that were assessed at multiple time points. Time-constant covariates included: educational attainment (less than a high school diploma, high school diploma, and more than a high school diploma), household income, age at delivery, city of delivery, parity after delivery, timing and type of prenatal care (obstetrician/gynecologist (OB/GYN), family medicine provider, certified nurse midwife/nurse practitioner, or a collaborative physician-midwife practice), type of delivery (vaginal or cesarean), whether the newborn was admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), whether the participant attended her postpartum checkup, and whether the participant became pregnant again within the first ten months postpartum. Time-changing covariates assessed at each time point included: current insurance type (public, private, or none), current Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) participation, current relationship status (single, cohabitating, married, or separated/divorced/widowed), current employment status, if they were currently enrolled in school, and current smoking behaviors.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted all analyses using Stata 14.0. We used chi-square tests to determine the significance of bivariate relationships between participant descriptive characteristics and breastfeeding behaviors and also country of origin. As we aimed to assess the influence of predictors on whether women would fall into one of three possible categories of breastfeeding behaviors at 3-months postpartum (not breastfeeding, supplementing, or exclusive breastfeeding), we initially selected a multinomial logistic regression model for its intuitive interpretation of results. However, the multinomial logistic regression model did not meet the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumption which asserts that the ratio of odds of belonging to any of the dependent categories is not systematically influenced by any of the other categories (41). Consequently, we fit a binomial logistic regression model including only the women currently breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum (n=288) to assess whether a woman’s nativity and country of education predicted breastfeeding women’s odds of supplementation v. exclusive breastfeeding after considering time-constant and changing covariates. We conducted a series of likelihood ratio tests which resulted in the inclusion of the city of delivery and work status at 3-months postpartum as covariates as they significantly improved model fit and yielded the most parsimonious model. We next conducted likelihood ratio tests to determine the best-fitting multivariate logistic regression models to determine current breastfeeding (yes/no) at each of the four time points (delivery, 3, 7, and 10-months postpartum). We fit models with the combination of covariates yielding the best-fitting model for each time point (see Table 3), and determined women’s predicted probabilities of breastfeeding at delivery, 3, 7, and 10-months postpartum holding all covariates at their means. We fit all multivariate models with complete cases in that only cases with information on each of the included covariates were included in each model at each time point. The number of cases (n) appear for each model in Table 3. We also conducted multivariate time series models (subject-specific and population-average models) as sensitivity analyses. As all models yielded similar findings, we present only the results from the multivariate logistic regression models in this paper for ease of interpretation.

RESULTS

Descriptive Characteristics

The three groups of participants, women born and educated in the U.S. (US-US), born in Mexico and educated in the U.S. (MX-US), and born and educated in Mexico (MX-MX), had considerably different time-constant descriptive characteristics. US-US women had higher levels of education, higher incomes, were younger at delivery with lower parity, and more often had cesarean deliveries than women born in Mexico, regardless of country of education (see Table 1). MX-MX women were older, more often married, and had higher parity than women educated in the U.S., regardless of country of birth. Women born in Mexico, both MX-MX and MX-US, more often obtained prenatal care from a source other than an OB/GYN compared to US-US women, and less often attended their postpartum checkups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Mexican-origin women in Postpartum Contraception Study, Austin and El Paso, Texas, 2012

| Characteristic | All n (%)1 |

Born in US & completed education in US n (%) |

Born in Mexico & completed education in

US n (%) |

Born in Mexico & completed education in

Mexico n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 593(100.0) | 221 (37.3) | 104 (17.5) | 268 (45.2) |

| Educational attainment** | ||||

| <High school diploma | 233 (39.2) | 40 (18.1) | 40 (38.5) | 152 (56.7) |

| High school diploma | 167 (28.1) | 77 (34.8) | 33 (31.7) | 57 (21.3) |

| >High school diploma | 194 (32.7) | 104 (47.1) | 31 (29.8) | 59 (22.0) |

| Income at delivery** | ||||

| <10,000 | 224 (38.3) | 63 (28.8) | 33 (33.0) | 128 (48.3) |

| 10,000–24,999 | 221 (37.8) | 73 (33.3) | 41 (41.0) | 106 (40.0) |

| 25,000–49,000 | 84 (14.4) | 38 (17.4) | 16 (16.0) | 30 (11.3) |

| 50,000 + | 56 (9.6) | 45 (20.6) | 10 (10.0) | 1 (0.38) |

| City | ||||

| Austin | 235 (39.6) | 87 (39.4) | 50 (48.1) | 98 (36.6) |

| El Paso | 358 (60.4) | 134 (60.6) | 54 (51.9) | 170 (63.4) |

| Age at delivery** | ||||

| 18–24 | 208 (35.0) | 110 (49.8) | 43 (41.4) | 55 (20.5) |

| 25–29 | 163 (27.4) | 47 (21.3) | 31 (29.8) | 85 (31.7) |

| 30–34 | 129 (21.7) | 37 (16.7) | 16 (15.4) | 76 (28.4) |

| 35+ | 94 (15.8) | 27 (12.2) | 14 (13.5) | 52 (19.4) |

| Parity after delivery** | ||||

| 1 | 168 (28.3) | 76 (34.4) | 30 (28.9) | 62 (23.1) |

| 2 | 176 (29.6) | 80 (36.2) | 28 (26.9) | 68 (25.4) |

| 3+ | 250 (42.1) | 65 (29.4) | 46 (44.2) | 138 (51.5) |

| Trimester started prenatal care | ||||

| No care | 20 (3.4) | 4 (1.8) | 5 (4.8) | 11 (4.1) |

| 1st | 430 (72.5) | 167 (76.0) | 73 (70.2) | 189 (70.5) |

| 2nd | 129 (21.8) | 45 (20.5) | 24 (23.1) | 60 (22.4) |

| 3rd | 14 (2.4) | 4 (1.8) | 2 (21.9) | 8 (3.0) |

| Prenatal provider type** | ||||

| OB/GYN | 462 (80.6) | 195 (89.9) | 71 (71.7) | 195 (76.2) |

| Family medicine | 31 (5.4) | 9 (4.2) | 4 (4.0) | 18 (7.0) |

| Certified nurse midwife/NP | 67 (11.7) | 11 (5.1) | 20 (20.2) | 36 (14.1) |

| Collaborative physician-midwife | 13 (2.3) | 2 (0.9) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (2.7) |

| Cesarean delivery** | 220 (37.0) | 108 (48.9) | 33 (31.7) | 79 (29.5) |

| Newborn in NICU | 19 (3.2) | 9 (4.1) | 2 (1.9) | 8 (3.0) |

| Attended postpartum checkup** | 461 (89.3) | 175 (95.1) | 88 (88.9) | 197 (84.9) |

| Public insurance at delivery (v. Private)** | 507 (85.4) | 153 (69.2) | 90 (86.5) | 263 (98.1) |

| Relationship status at delivery* | ||||

| Single | 124 (20.9) | 50 (22.7) | 21 (20.2) | 53 (19.8) |

| Cohabitating | 188 (31.7) | 85 (38.6) | 32 (30.8) | 70 (26.1) |

| Married | 271 (45.7) | 82 (37.3) | 49 (47.1) | 140 (52.2) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 10 (1.7) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (1.9) | 5 (1.9) |

| Participating in WIC | ||||

| Delivery* | 377 (63.5) | 134 (60.6) | 80 (76.9) | 162 (60.5) |

| 3 months** | 380 (67.9) | 123 (57.5) | 84 (83.2) | 172 (70.5) |

| 7 months* | 393 (70.2) | 135 (65.5) | 84 (82.4) | 173 (68.9) |

| 10 months* | 378 (73.1) | 122 (67.4) | 81 (81.8) | 174 (73.7) |

| Currently smoking | ||||

| 3 months | 18 (3.7) | 11 (6.4) | 2 (2.1) | 5 (2.3) |

| 7 months | 25 (4.8) | 13 (7.2) | 2 (2.0) | 10 (4.2) |

| 10 months* | 39 (8.0) | 21 (12.6) | 4 (4.2) | 14 (6.2) |

| Currently working | ||||

| 3 months** | 147 (30.1) | 86 (50.0) | 25 (26.0) | 35 (15.9) |

| 7 months** | 184 (35.5) | 97 (53.0) | 34 (34.3) | 53 (22.5) |

| 10 months** | 184 (37.7) | 94 (56.3) | 30 (31.6) | 60 (26.7) |

| Currently in school | ||||

| 3 months | 48 (9.8) | 24 (14.0) | 8 (8.3) | 16 (7.3) |

| 7 months* | 60 (11.6) | 30 (16.5) | 13 (13.1) | 17 (7.2) |

| 10 months | 45 (9.2) | 19 (11.4) | 9 (9.5) | 17 (7.6) |

| Additional pregnancy within 10 months | 29 (6.0) | 13 (7.9) | 6 (6.3) | 10 (4.5) |

p<.05;

p<.005 for χ2 tests of characteristic across all three groups

not all percentages sum to 100% due to missing data; n varies by wave #

Similarly, participants’ postpartum time-changing characteristics varied by nativity and country of education. US-US women more often had private insurance, worked at 3 – 10 months postpartum, attended school at 7 months postpartum, and smoked at 10 months postpartum than women born in Mexico (MX-MX and MX-US) (see Table 1). MX-MX women were more often married, and more often uninsured than women educated in the U.S., regardless of country of birth (MX-US and US-US). MX-US women were more often participating in WIC at each time point than MX-MX and US-US.

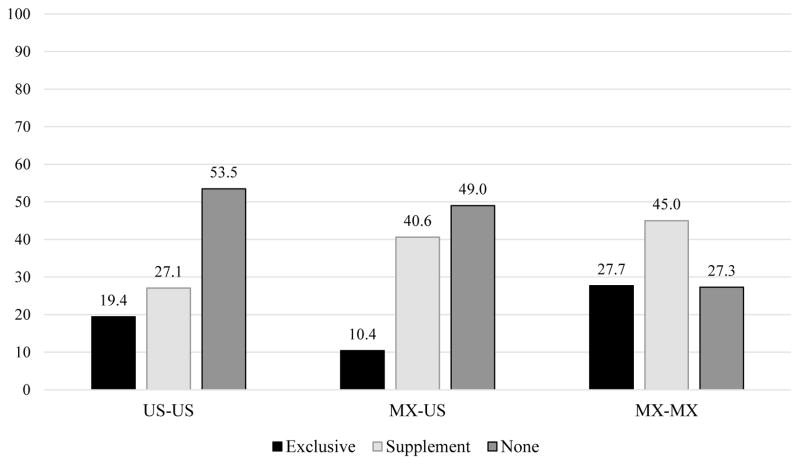

MX-MX women had the highest rates of breastfeeding at delivery (92.9%) in bivariate models (see Table 2). MX-US and US-US women had similar rates of breastfeeding at delivery (80.8% and 79.2%, respectively). These trends continued through 10 months postpartum as rates of breastfeeding steadily declined for all three groups from delivery to 10 months postpartum. The unadjusted percentages of women exclusively breastfeeding, supplementing, and not breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum by country of birth and schooling are presented in Figure 1. Among all mothers at 3-months postpartum (regardless of infant feeding method), 27.7% of MX-MX women were exclusively breastfeeding compared to 19.4% of US-US women and 10.4% of MX-US women (see Figure 1). However, out of only the women who were currently breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum, US-US women had higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding (41.8%) than MX-US (20.4%) and MX-MX (38.1%) women (not shown).

Table 2.

Number and percentage of Mexican-origin women currently breastfeeding at delivery, 3 months, 7 months, and 10 months postpartum by nativity and country of education, Austin and El Paso, 2012

| All | Born in US & completed education in US (n=221) | Born in Mexico & completed education in US (n=104) | Born in Mexico & completed education in Mexico (n=268) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | |

| Breastfeeding at delivery (n=594) | 21.04** | ||||

| Yes | 509 (85.7) | 175 (79.2) | 84 (80.8) | 249 (92.9) | |

| No | 85 (14.3) | 46 (20.8) | 20 (19.2) | 19 (7.1) | |

| Breastfeeding at 3 months (n=489) | 30.78** | ||||

| Yes | 290 (59.3) | 80 (46.5) | 49 (51.0) | 160 (72.7) | |

| No | 199 (40.7) | 92 (53.5) | 47 (49.0) | 60 (27.3) | |

| Breastfeeding at 7 months (n=519) | 29.60** | ||||

| Yes | 209 (40.3) | 54 (29.5) | 29 (29.3) | 125 (53.0) | |

| No | 310 (59.7) | 129 (70.5) | 70 (70.7) | 111 (47.0) | |

| Breastfeeding at 10 months (n=488) | 17.44** | ||||

| Yes | 146 (29.9) | 36 (21.6) | 21 (22.1) | 88 (39.1) | |

| No | 342 (70.1) | 131 (78.4) | 74 (77.9) | 137 (60.9) | |

p<.05;

p<.005

Figure 1.

Unadjusted percentages of not breastfeeding, supplementing, and exclusive breastfeeding by country of birth and schooling at 3 months postpartum for Mexican-origin women from the Postpartum Contraception Study, Austin and El Paso, Texas, 2012. (N=489)

Abbreviations: US-US: born and educated in the United States; MX-US: born in Mexico and educated in the United States; MX-MX: born and educated in Mexico.

Exclusive v. Supplemental Breastfeeding at 3-months Postpartum

The odds of exclusive (v. supplemental) breastfeeding among the breastfeeding women were 66% lower for MX-US women than for US-US women after the inclusion of covariates determined to yield the best-fitting multivariate logistic regression model. However, there was no significant difference in exclusive (v. supplemental) breastfeeding between US-US and MX-MX women (see Table 3). Further, the difference in exclusive v. supplementing behaviors for women born in Mexico and completing schooling in the two different countries did not reach significance at conventional levels. Among breastfeeding women at 3 months postpartum, those who delivered in El Paso had 1.9 times the odds of exclusively breastfeeding compared to women from Austin. Also, breastfeeding women who had returned to work by 3 months postpartum had 48% lower odds of exclusive breastfeeding compared to breastfeeding women who were not working.

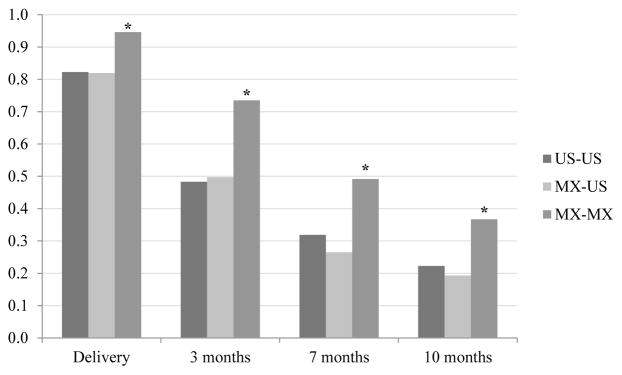

Current Breastfeeding from Delivery to 10 months Postpartum

MX-MX women had 3.8 times the odds of breastfeeding of US-US women at delivery. This trend continued, but attenuated, over 3, 7, and 10 months postpartum (see Table 3). MX-US women had similar odds of breastfeeding throughout the study period as US-US women. The predicted probabilities of breastfeeding at each time point are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Adjusted probabilities of breastfeeding from delivery to 10 months postpartum by country of birth and schooling for Mexican-origin women from the Postpartum Contraception Study, Austin and El Paso, Texas, 2012.

*MX-MX significantly higher than US-US and US-MX at each time point at p<.05.

Abbreviations: US-US: born and educated in the United States; MX-US: born in Mexico and educated in the United States; MX-MX: born and educated in Mexico.

All other covariates held at their means.

The odds ratios of breastfeeding and exclusively breastfeeding by time-constant and time-changing characteristics appear in Table 3. Women who delivered in Austin had approximately twice the odds of breastfeeding, compared to women from El Paso. This trend held through 10 months postpartum but did not reach statistical significance at 7 months postpartum. At delivery, primiparous women had over 60% higher odds of breastfeeding over multiparous women in the multivariate model. Similarly, mothers whose infants were admitted to the NICU had nearly 70% lower odds of breastfeeding of the mothers whose infants were not admitted to the NICU after delivery. Married women had over three times the odds of breastfeeding at delivery of non-married women. From three to ten months postpartum, current smoking status, work status, and relationship status each significantly predicted breastfeeding in multivariate models. Smokers had 68–75% lower odds of breastfeeding across the three time points; married women had 73–78% higher odds at 3 and 7 months postpartum; working women had 41–54% lower odds at 7 and 10 months postpartum.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds of currently breastfeeding at 3, 7, and 10 months postpartum, and of exclusively breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum for Mexican-origin women from the Postpartum Contraception Study, Austin and El Paso, Texas, 20121

| Currently breastfeeding (v. not breastfeeding) | Exclusively breastfeeding (v. supplementing) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| At delivery (n=586) | 3 months postpartum (n=484) | 7 months postpartum (n=515) | 10 months postpartum (n=486) | 3 months postpartum (n=288) | |

| Time-constant characteristics | |||||

| Nativity & Place of Education | |||||

| U.S.-U.S. (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mexico-U.S. | 0.98 (0.52–1.85) | 1.05 (0.63–1.78) | 0.77 (0.44–1.36) | 0.83 (0.44–1.56) | 0.34 (0.14–0.81) |

| Mexico-Mexico | 3.80 (2.05–7.03) | 2.97 (1.91–4.62) | 2.08 (1.33–3.23) | 2.01 (1.24–3.26) | 0.72 (0.39–1.31) |

| City | |||||

| Austin (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| El Paso | 0.52 (0.30–0.89) | 0.60 (0.40–0.89) | 0.69 (0.47–1.02) | 0.51 (0.34–0.76) | 1.93 (1.16–3.20) |

| Parity after delivery | |||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||

| 2 | 0.38 (0.19–0.76) | ||||

| 3+ | 0.36 (0.18–0.71) | ||||

| Newborn in NICU | |||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.30 (0.11–0.88) | 0.12 (0.02–0.94) | |||

| Time-changing characteristics | |||||

| Current relationship status | |||||

| Single (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Cohabitating | 1.24 (0.67–2.28) | 0.82 (0.48–1.41) | 1.21 (0.68–2.15) | ||

| Married | 3.07 (1.59–5.92) | 1.78 (1.07–2.97) | 1.73 (1.03–2.91) | ||

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 0.65 (0.13–3.18) | 0.22 (0.04–1.22) | 0.88 (0.27–2.79) | ||

| Currently smoking | |||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.27 (0.09–0.82) | 0.29 (0.09–0.91) | 0.32 (0.11–0.92) | ||

| Currently working | |||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.46 (0.30–0.70) | 0.59 (0.37–0.93) | 0.52 (0.27–0.99) | ||

Each model adjusted for covariates determined to provide the best-fitting multivariate model through a series of likelihood-ratio tests which appear in the table. Covariates considered in likelihood ratio tests at each time point included: educational attainment, income, city, age, parity, NICU status, prenatal care timing and provider, vaginal v. cesarean delivery, postpartum checkup attendance, relationship status, insurance type, work and school status, smoking status, participation in WIC, and whether the participant had an additional pregnancy during the study period.

Bolded values indicate p<.05.

Numbers presented in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we examined the combined association of nativity and country of education with Mexican-origin women’s breastfeeding patterns at delivery through 10 months postpartum controlling for influential time-constant and time-changing characteristics. In bivariate models, women born and educated in Mexico had higher rates of breastfeeding than women educated in the U.S., regardless of country of birth, throughout the study period. This trend held in multivariate models although the gap closed over time. In previous research, foreign-born women have demonstrated higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration rates than native-born women (6). However, our findings suggest that country of schooling may be a better predictor of Mexican-origin women’s breastfeeding initiation and duration as women born in Mexico and educated in the U.S. had similar odds of current breastfeeding as women born and educated in the U.S. at each time point in the study. In some ways, this finding parallels previous research observing that time lived in the U.S. is inversely related to Mexican-origin women’s breastfeeding duration (10). However, as women born in Mexico come to the U.S. at different points in their lives, dissimilar to the net amount of time lived in the U.S., country of schooling typically represents where a woman lived during periods of social and behavioral development critical to informing many health behaviors in adulthood (28).

Exclusive breastfeeding patterns among breastfeeding women at 3 months postpartum were not as clear as initiation and duration patterns. The phenomenon of “los dos” where women with stronger ties to Mexican norms report supplementing breastfeeding with formula feeding their newborns would suggest that women born and educated in the U.S. would have the highest odds of exclusive breastfeeding, followed by women born in Mexico and educated in the U.S., and that women born and educated in Mexico would have the lowest odds of exclusive breastfeeding. In our analytic sample, breastfeeding women born in Mexico and educated in the U.S. (MX-US) had lower rates of exclusive breastfeeding than women born and educated in Mexico (MX-MX) and women born and educated in the U.S. (US-US). This finding suggests that the mechanisms that support exclusive breastfeeding among women born and educated in the U.S. and women born and educated in Mexico may differ, and should be explored in future research. It is also possible that these two groups of women’s supplementing practices are different from one another, which we did not capture in our measurement of supplementation. For example, participants were categorized as supplementing if they primarily breastfed and were beginning to introduce solid foods, or if they were primarily giving formula and occasionally breastfed. As these two supplementing practices provide very different nutritional profiles for infants, future studies should consider these more nuanced differences in supplementation behaviors in their measurements. In previous studies of U.S. Latina women’s exclusive breastfeeding patterns, the evidence is mixed regarding whether Latina women with stronger ties to their Latin American country of origin exclusively breastfeed more often and for longer durations (8,10–12) or if they are at elevated risk for “los dos” (13–15). The difference in findings we see in the current study compared to previous research may be due to differences in measurement of Latina women’s ties to their country of origin, to the differences in how excusive breastfeeding is measured across studies, or to the fact that our sample consists entirely of women of Mexican origin while other studies do not specify Hispanic/Latina women’s country of origin. One previous study assessing exclusive breastfeeding specifically among Mexican-origin women found increased years of residence in the U.S. to be associated with shorter duration of exclusive breastfeeding (10). Exclusivity was determined prior to 6 months postpartum by asking the mother if she had given her infant formula, whereas in the current study, the mothers were considered to be supplementing if they had given their child “anything” besides breastmilk. Such differences in assessing supplementation, as well as the differences in study locations (urban cities in Texas v. an agricultural area of California), may explain differences in findings. Further, as previously mentioned, the location of where a woman completed her most recent year of schooling may or may not be a proxy for how long she has lived in the country—depending on the woman’s age and stage of life when she moved to the U.S.

This study had several strengths. First, we prospectively assessed current breastfeeding behaviors through ten months postpartum whereas the majority of research reports women’s breastfeeding behaviors retrospectively or prospectively assesses behavior for shorter postpartum durations. The data also provided information about women’s pre and postnatal behaviors and contexts, allowing us to comprehensively account for influential factors in multivariate models such as relationship, work, and smoking status. Further, in considering the association of country of origin with mothers’ breastfeeding behaviors, we investigated the effects of both nativity and schooling, thereby taking into account the influences of country of birth, educational background, and the environmental context during formative years in predicting mothers’ behaviors.

However, this study is not without limitations. The participants in this study were patients at three hospitals in El Paso and Austin, Texas. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to women from other regions. Interviews did not take place precisely at 3, 7, and 10 months postpartum (M=3.5, S.D.=1.4; M=7.0, S.D.=1.3; M=9.9, S.D.=0.8, respectively) and the date of breastfeeding cessation or initiation of supplementation after 3 months postpartum was not reported. Future studies should include these dates or child ages to enhance the precision of estimation of women’s overall and exclusive breastfeeding rates at each time point. Further, as previously mentioned, the degree and type of breastfeeding supplementation was not assessed in this study and should be included in future research for a more nuanced understanding of the predictors of supplementing behaviors. Future studies could also include women’s nativity and place of education with other measures, such as length of residence in the U.S. and parents’ nativity, in models to assess the relative importance of these contextual factors on women’s breastfeeding behaviors.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that in clinical practice, country of schooling should be considered when assessing Mexican-origin women’s risk for breastfeeding discontinuation and in developing culturally-resonant, breastfeeding promotion initiatives. The protective factors associated with completing schooling in Mexico should continue to be explored in future research to determine which mediating factors could be translated into breastfeeding promotion efforts for Mexican-origin women completing their education in the U.S. Finally, efforts should be made to identify the barriers and facilitators to breastfeeding among U.S.-educated Mexican-origin women, to enhance existing breastfeeding promotion efforts in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the Susan T. Buffett Foundation and by a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) center grant (R24 HD042849) and training program grant (T32 HD007081) awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Hendrick, C. E., & Potter, J. E. (2017). Nativity, Country of Education, and Mexican-Origin Women’s Breastfeeding Behaviors in the First 10 Months Postpartum. Birth, 44(1), 68-77. which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/birt.12261. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving.

References

- 1.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. [Accessed Jan 31, 2016];Population Estimates and Projections. 2015 Available at: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf.

- 2.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed Jan 31, 2016];American FactFinder Results: Hispanice or Latino Origin by Specific Origin 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. 2014 Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

- 3.Krogstad JM, Lopez MH. Hispanic Nativity Shift: U.S. births drive population growth as immigration stalls. PewResearch Center Hispanic Trends; 2014. [Accessed Feb 1, 206]. Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/04/29/hispanic-nativity-shift/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pew Research Center. The Mexican-American Boom: Births Overtake Immigration. [Accessed Jun 26, 2016];Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. 2011 Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2011/07/14/the-mexican-american-boom-brbirths-overtake-immigration/

- 5.Barcelona de Mendoza V, Harville E, Theall K, et al. Acculturation and intention to breastfeed among a population of predominantly Puerto Rican women. Birth. 2016;43(1):78–85. doi: 10.1111/birt.12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh GK, Kogan MD, Dee DL. Nativity/immigrant status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic determinants of breastfeeding initiation and duration in the United States, 2003. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Supplement 1):S38–S46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson MV, Diaz VA, Mainous AG, Geesey ME. Prevalence of breastfeeding and acculturation in Hispanics: results from NHANES 1999–2000 study. Birth. 2005;32(2):93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill SL. Breastfeeding by Hispanic women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(2):244–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rassin DK, Markides KS, Baranowski T, Richardson CJ, Mikrut WD, Bee DE. Acculturation and the initiation of breastfeeding. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(7):739–746. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harley K, Stamm NL, Eskenazi B. The effect of time in the US on the duration of breastfeeding in women of Mexican descent. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(2):119–125. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0152-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorman JR, Madlensky L, Jackson DJ, Ganiats TG, Boies E. Early postpartum breastfeeding and acculturation among Hispanic women. Birth. 2007;34(4):308–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahluwalia IB, D’Angelo D, Morrow B, McDonald JA. Association between acculturation and breastfeeding among hispanic women data from the pregnancy risk assessment and monitoring system. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(2):167–173. doi: 10.1177/0890334412438403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartick M, Reyes C. Las dos cosas: an analysis of attitudes of latina women on non-exclusive breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(1):19–24. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunik M, Clark L, Zimmer LM, Jimenez LM, O’Connor ME, Crane LA, et al. Early infant feeding decisions in low-income Latinas. Breastfeed Med. 2006;1(4):225–235. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldrop J. Exploration of reasons for feeding choices in Hispanic mothers. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2013;38(5):282–288. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e31829a5625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thulier D, Mercer J. Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(3):259–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott JA, Binns CW, Oddy WH, Graham KI. Predictors of breastfeeding duration: evidence from a cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e646–e655. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(5):973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valencia EY, Johnson V. Acculturation among Latino youth and the risk for substance use: Issues of definition and measurement. J Drug Issues. 2008;38(1):37–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudmin F. Constructs, measurements and models of acculturation and acculturative stress. Int J Intercult Relat. 2009;33(2):106–123. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(7):1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman DJ, Pérez-Escamilla R. Acculturative type is associated with breastfeeding duration among low-income Latinas. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(2):188–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimbro RT, Lynch SM, McLanahan S. The influence of acculturation on breastfeeding initiation and duration for Mexican-Americans. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2008;27(2):183–199. doi: 10.1007/s11113-007-9059-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrd TL, Balcazar H, Hummer RA. Acculturation and breast-feeding intention and practice in Hispanic women on the US-Mexico border. Ethn Dis. 2000;11(1):72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sussner KM, Lindsay AC, Peterson KE. The influence of acculturation on breast-feeding initiation and duration in low-income women in the US. J Biosoc Sci. 2008;40(5):673–696. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007002593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson MK, Crosnoe R, Elder GH. Insights on adolescence from a life course perspective. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(1):273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57(1):255–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behav Health Educ Theory Res Pract. 2008;4:465–486. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potter JE, Moore AM, Byrd TL. Cross-border procurement of contraception: Estimates from a postpartum survey in El Paso, Texas. Contraception. 2003;68(4):281–7. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(03)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonuck KA, Freeman K, Trombley M. Country of origin and race/ethnicity: Impact on breastfeeding intentions. J Hum Lact. 2005;21(3):320–326. doi: 10.1177/0890334405278249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Celi AC, Rich-Edwards JW, Richardson MK, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW. Immigration, race/ethnicity, and social and economic factors as predictors of breastfeeding initiation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(3):255–260. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merewood A, Brooks D, Bauchner H, MacAuley L, Mehta SD. Maternal birthplace and breastfeeding initiation among term and preterm infants: A statewide assessment for Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1048–e1054. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson AK, Himmelgreen DA, Peng Y-K, et al. Social capital and breastfeeding initiation among Puerto Rican women. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:283–286. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson-Davis CM, Brooks-Gunn J. Couples’ immigration status and ethnicity as determinants of breastfeeding. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):641–646. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Escarce J, Morales L, Rumbaut R. The health status and health behaviors of Hispanics. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the Future of America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006. pp. 362–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potter JE, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, Hubert C, Stevenson AJ, White K, et al. Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception. 2014;90(5):488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Rossem L, Oenema A, Steegers EA, Moll HA, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, et al. Are starting and continuing breastfeeding related to educational background? The generation R study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):e1017–e1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newton KN, Chaudhuri J, Grossman X, Merewood A. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding among Latina women giving birth at an inner-city baby-friendly hospital. J Hum Lact. 2009;25(1):28–33. doi: 10.1177/0890334408329437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones JR, Kogan MD, Singh GK, Dee DL, Grummer-Strawn LM. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1117–1125. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McFadden D. Regression-based specification tests for the multinomial logit model. J Econom. 1987;34(1):63–82. [Google Scholar]