Abstract

Biologics are the most rapidly growing class of therapeutics, but commonly suffer from low stability. Peroral administration of these therapeutics is an attractive delivery route; however, this route introduces unique physiological challenges that increase the susceptibility of proteins to lose function. Formulation of proteins into biomaterials, such as electrospun fibers, is one strategy to overcome these barriers, but such platforms need to be optimized to ensure protein stability and maintenance of bioactivity during the formulation process. This work develops an emulsion electrospinning method to load proteins into Eudragit® L100 fibers for peroral delivery. Horseradish peroxidase and alkaline phosphatase are encapsulated with high efficiency into fibers and released with pH-specificity. Recovery of protein bioactivity is enhanced through reduction of the emulsion aqueous phase and the inclusion of a hydrophilic polymer excipient. Finally, we show that formulation of proteins in lyophilized electrospun fibers extends the therapeutic shelf life compared to aqueous storage. Thus, this platform shows promise as a novel dosage form for the peroral delivery of biotherapeutics.

Keywords: emulsion electrospinning, nanofibers, protein delivery, peroral drug delivery, controlled release

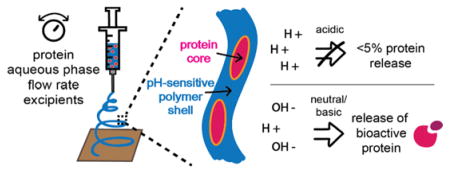

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

While the development of biological products has increased dramatically in the last three decades, the delivery of protein therapeutics remains particularly challenging (Mitragotri et al., 2014). Proteins are large marcromolecules that require a precise 3D structure to carry out their function. Due to this structural complexity, loss of protein activity can occur in response to a variety of factors that cause protein stress and changes in conformation such as temperature, pH, ultraviolet light, and interaction with organic solvents. In the clinical application of such biopharmaceutics, the route of administration introduces a variety of these unique challenges. Peroral administration, through swallowing of a solution or pill, is one of the most attractive routes for therapeutic delivery, as patient comfort is increased, the use of needles is eliminated, and local delivery to the gastrointestinal tract can be achieved, reducing systemic side effects (Levine and Dougan, 1998). However, peroral delivery of proteins is difficult due to the inherent barrier of the acidic environment of the stomach, which can result in protein degradation, leading to low bioavailability and the need for multiple doses (Goldberg and Gomez-Orellana, 2003; Pawar et al., 2014). Recently, a variety of nanotechnology platforms utilizing biomaterials have been developed to overcome these challenges in biologic formulation and peroral delivery to the gut (Gupta et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2016).

Electrospinning is a technique that has been explored in the pharmaceutical nanotechnology field to develop materials as scaffolds for tissue engineering and for the delivery of small molecule therapeutics (Sill and von Recum, 2008). The electrospinning platform has many advantages compared to other formulations such as particulates, films, and tablets, including the versatility of polymers that can be employed to tailor release kinetics and therapeutic targeting for specific applications, high encapsulation efficiency, which is critical when loading high-cost therapeutics, high surface-area-to-volume ratio for enhanced interaction with the tissue of interest, and ease of production (Agarwal et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2014; Sill and von Recum, 2008). In the last 10 years, electrospun nanofibers have been investigated for the delivery of larger, less stable therapeutics such as protein biologics and have proven to be advantageous in terms of controlled delivery and enhancing protein stability (Ji et al., 2011). While protein encapsulation into nanofibers has been primarily developed for the production of bioactive scaffolds, we expect this platform holds promise for the targeted delivery of proteins to the gut with the proper design and optimization.

Proteins can be loaded into electrospun nanofibers by a method called emulsion electrospinning, which forms core-shell nanofibers from an emulsion comprised of an organic phase (containing polymer), surfactant, and aqueous phase (containing protein) (Yarin, 2011). In the emulsion electrospinning process, a high voltage is applied to the solution as it is pumped out of a needle and syringe until electrostatic forces overcome droplet surface tension. This results in the formation of a Taylor cone and the ejection of a polymer jet that is electrically charged (Reneker and Chun, 1996; Yarin et al., 2001). As this charged jet moves through an electric field to be deposited onto a grounded collector as elongated fibers, the organic solvent evaporates more quickly than water and the emulsion droplets move inward and are stretched to form fibers with a continuous core surrounded by a viscous polymer shell (Sanders et al., 2003; Shastri et al., 2009). This architecture is advantageous for enhancing protein stability and controlled protein release compared to blend electrospinning, which directly exposes proteins to organic solvents and exhibits burst release kinetics (Ji et al., 2011). However, since in emulsion electrospinning proteins in the aqueous phase may still interact with organic solvents throughout the process, maintenance of protein bioactivity and stability must be optimized to prevent loss of protein structure, and thus function. In many studies that load non-enzymatic proteins into electrospun fibers, function is demonstrated but protein activity is not able to be quantified (Briggs et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015), and only a few studies have investigated the effects of emulsion electrospinning solution and processing parameters on maintaining protein bioactivity (Briggs and Arinzeh, 2014; Pinto et al., 2015; Place et al., 2016). Learning from these studies, it is clear that many parameters can significantly affect protein loading and activity and that the main challenges of high protein loading efficiency and bioactivity preservation still remain. In particular, previous studies have elucidated that each delivery system must be optimized based on electrospinning method, processing parameters, and the polymers and proteins used to ensure appropriate formulation of active, stable proteins in nanofibers. Additionally, the stability of therapeutic proteins loaded in electrospun fibers over time has not been widely studied. This shelf life is critical to evaluate, understand, and improve for the translation of such protein delivery platforms to clinical use.

The methacrylic acid and methyl methacrylate co-polymer Eudragit® L100 has been used in clinical settings as a capsule for the peroral delivery of therapeutics as it demonstrates pH-dependent solubility in neutral and basic conditions. This polymer has been applied to electrospinning and Eudragit®-based nanofibers have been used for small molecule drug delivery, stent coatings, antibacterial mats, and contrast agents for imaging (Aguilar et al., 2015; Bruni et al., 2015; Hamori et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2011). In the space of protein therapeutics, one study loaded human growth hormone into Eudragit® fibers using blend electrospinning for buccal drug delivery and demonstrated successful fabrication and wound healing function, but did not investigate how protein function was affected by the process (Choi et al., 2015).

The encapsulation of more diverse proteins, such as larger protein antigens or complex therapeutic antibodies, into Eudragit® fibers has not been investigated nor has the emulsion electrospinning of protein-loaded Eudragit® fibers, which can address problems in loss of protein function during formulation. The development of such a system would be advantageous for the delivery of proteins to targets in the intestinal tract, either to improve patient comfort in therapeutic administration, to access the mucosal immune system, or to address intestine-specific diseases (Date, 2016; Davitt and Lavelle, 2015; Ilan, 2016). Thus, in this study we aimed to optimize the electrospinning of two diverse proteins into Eudragit® L100 nanofibers. Specifically, we investigated the solution and processing parameters of emulsion electrospinning to achieve high protein loading into nanofibers, retention of protein bioactivity, extended formulation stability, and pH-controlled protein release for future applications in peroral therapeutic delivery to the intestinal tract.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Eudragit® L100 was a gift from Evonik Industries (Essen, Germany). N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) (anhydrous, 99.8%), poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) (30,000–70,000 g mol−1, 87–95% hydrolyzed), Tween® 20 (polysorbate 20), albumin–fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (FITC-BSA), alkaline phosphatase (AP) from bovine intestinal mucosa (≥10 DEA units mg−1 solid), sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (50% in H2O), alkaline phosphatase yellow (pNPP) liquid substrate system, and magnesium chloride (MgCl2) (anhydrous, ≥98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), Micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit, and Karl Fischer titration reagents AQUASTAR™ CombiMethanol and Combititrant 5 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Hydrochloric acid (HCl) (36.5%–38.0%) was purchased from Avantor Performance Materials (Center Valley, PA, USA). Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) was purchased from Corning Inc. (Corning, NY, USA). TMB substrate set was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Tris-HCl (Tris-hydrochloride, molecular biology grade) was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Sodium chloride (NaCl) was purchased from EMD Millipore (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). Ethanol (EtOH) (200 proof) was purchased from the University of Washington’s chemistry supply store.

2.2. Emulsion Electrospinning

Eudragit® L100 was dissolved at 15% (wt/vol) in a solution of 4:1 (vol:vol) EtOH:DMF. Non-ionic surfactant Tween® 20 was added to the stirring Eudragit® solution at 0.4% (vol/vol) in 20 mL glass scintillation vials. Aqueous protein solutions were dropped into the stirring Eudragit® and surfactant solution at either 5% or 20% (vol/vol). Protein loading was kept constant at 1 wt%. The solution was emulsified for 10 minutes by constant stirring at high speed then loaded into a 1 mL glass syringe with a 21G stainless steel blunt needle for electrospinning on a needle rig set-up utilizing a syringe pump and voltage source. We chose high speed stirring over sonication for emulsification, as sonication has been shown to have an effect on secondary protein structure (Yang et al., 2008a). The solution was electrospun onto a wax paper substrate on a grounded metal collector at a distance of 10–12 cm. A constant voltage of 12.5 kV was applied and the flow rate was varied between formulations to determine its effect on protein bioactivity. Low and high flow rate formulations were electrospun at 25 and 40 μL min−1, respectively. Electrospinning was performed at room temperature in a fume hood. Protein-loaded fibers were stored in sealed bags at room temperature unless stated otherwise.

2.3. Characterization of Protein-Loaded Electrospun Fibers

2.3.1. Microscopy of Protein-Loaded Electrospun Fibers

Electrospun fibers were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Sirion XL30 SEM and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a Tecani G2 F20 Supertwin operating at 200 kV (Molecular Analysis Facility, University of Washington). For SEM imaging, fiber samples were mounted on carbon tape and sputter coated with gold and palladium before imaging. Image settings of 5 kV, spot size of 2, and a working distance of 5 mm were used. Fiber diameters were measured using ImageJ software (NIH) by bisectioning each image diagonally with a line and manually measuring diameters for fibers that intersected the line. At least 30 fibers were measured per fiber formulation sample. Samples for TEM imaging were prepared by electrospinning fibers onto copper-coated TEM grids.

The location of protein within the fibers was determined by electrospinning FITC-BSA into Eudragit® L100 as described above. Briefly, FITC-BSA was dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 1 mg ml−1 and dropped into a spinning solution of 15 wt% Eudragit® L100 in 4:1 DMF:EtOH (vol:vol) and Tween® 20 (0.4 vol%). FITC-BSA was added to achieve emulsions with 5% and 20% aqueous phases. Emulsification proceeded for 10 minutes and was then loaded into a 1 mL glass syringe with a 21G stainless steel blunt needle for electrospinning on a needle rig set-up utilizing a syringe pump and voltage source. The solution was electrospun at a constant voltage of 12.5 kV and a flow rate of 25 μL min−1 onto a wax paper substrate on a grounded metal collector at a distance of 10–12 cm. Electrospinning was performed at room temperature in a fume hood. Protein-loaded fibers were transferred to glass slides and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with an Andor (model number DR-328G-C01-SIL) fluorescence camera (Andor, Belfast, UK).

2.3.2. Kinetics of Protein Release in Dynamic pH Conditions

Protein release from fibers was investigated under dynamic pH conditions, mimicking oral-to-intestinal transit after ingestion, focused on the lower stomach and small intestine. Fiber samples were cut, massed, and placed in 20 mL scintillation vials. Three samples from the fiber mat were analyzed for each formulation. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (1x) was pH-adjusted to 2 using 1M HCl and added to the scintillation vials at 2 mg fiber/mL PBS. Vials were placed on an orbital shaker (150 rpm) at 37 °C. At each time point, 500 μL samples were removed and the volume was replaced with PBS pH 2. After the 4 hour time point sample was taken, the volume was replaced with 470 μL PBS pH 7 and 30 μL 1M NaOH to increase the pH to 7. The pH change was verified for one representative sample. Volume replacement was performed with PBS pH 7 for the remainder of the time points. The Micro BCA assay was used to determine protein concentrations released over time using a standard curve with known protein concentrations and performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein standards in PBS pH 2 and 7 and in solutions of blank Eudragit® L100 electrospun fibers dissolved in PBS pH 7 were included to account for assay interference. Sample dilution during the experiment was accounted for by incorporating the mass removed from each time point in data analysis calculations.

2.3.3. Protein Encapsulation Efficiency

Encapsulation efficiency was calculated based on the amount of protein recovered from the fiber after 24 hours of incubation in PBS pH 7 at 37 °C when the fiber was fully dissolved using equation (1).

| (1) |

2.4. Quantification of Bioactivity of Proteins Released from Electrospun Fibers

Bioactivity retention of encapsulated proteins was determined by kinetic colorimetric substrate assays of the proteins recovered from each fiber formulation at day 0, 1 week, and 4 weeks. Three samples from the fiber mat were analyzed for each formulation. For HRP activity quantification, fibers were massed (5 ± 1 mg) and placed in 20 mL scintillation vials. PBS (1x, pH-unadjusted) was added for a fiber concentration of 0.5 mg mL−1 and vials were placed on a tube rotator at room temperature for 30 minutes or until fully dissolved. Serial dilutions were performed to achieve an HRP concentration of 5 ng mL−1. To a 96-well clear, flat bottom plate, 100 μL of each sample or freshly prepared 5 ng mL−1 HRP controls were added per well and 50 μL of TMB substrate solution (1:1 Substrate A:Substrate B, vol:vol) was added to start the assay. Change in absorbance at 652 nm was monitored every 15 seconds using a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO microplate reader (Männedorf, Switzerland) over 10 minutes. For AP activity quantification, fibers were massed (5 ± 1 mg) and placed in 20 mL scintillation vials. AP buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05 vol% Tween 20, pH 9.5) was added for a fiber concentration of 1 mg mL−1 (10 μg mL−1 AP concentration) and vials were placed on a tube rotator at room temperature for 30 minutes or until fully dissolved. To a 96-well clear, flat bottom plate, 100 μL of each sample or freshly prepared 10 μg mL−1 AP controls were added per well and 100 μL of 10x diluted pNPP substrate solution was added to start the assay. Change in absorbance at 405 nm was monitored every 15 seconds using a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO microplate reader over 10 minutes. For both proteins, the maximum increase in absorbance per minute (max slope) from the initial linear portion was determined and the retained protein bioactivity from the fibers was calculated using equation (2).

| (2) |

To determine the stability of proteins in the fibers over time, fibers were stored in sealed bags at room temperature for 4 weeks and assayed for activity at weeks 1 and 4. HRP (5 ng mL−1) and AP (10 μg mL−1) in PBS at room temperature were used as controls stored in aqueous conditions for the stability studies.

2.5. Characterization of Lyophilized Electrospun Fibers

2.5.1. Quantification of Fiber Water Content

Water content of each fiber formulation was determined by Karl Fischer titration using a V20 Volumetric KF Titrator (Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA). Briefly, a titration beaker was filled with solvent (CombiMethanol) and a pre-massed fiber sample (10 – 20 mg) was added to the stirring solution. A colorimetric titration was then automatically performed using titrant reagent (Combititrant 5) and the percent water content of the total sample mass was determined by the software. Three samples from the fiber mat were analyzed for each formulation. The water content of protein-loaded fibers was analyzed immediately after electrospinning, one day after electrospinning stored at room temperature, and one day after electrospinning stored under lyophilization. After lyophilization overnight, fibers were removed from vacuum and stored in the same conditions as the non-lyophilized fibers at room temperature for a total storage time of 7 days.

2.5.2. Quantification of Bioactivity of Proteins Released from Lyophilized Electrospun Fibers

Bioactivity of the proteins recovered from electrospun fibers with or without one-time lyophilization was determined by kinetic colorimetric assays as described above in Experimental Section 2.4.1.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. When comparing outcomes between groups, statistical analysis was performed by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s or Sidak’s multiple comparison post-test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 (*).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Protein-Loaded Eudragit® L100 Emulsion Electrospun Fibers

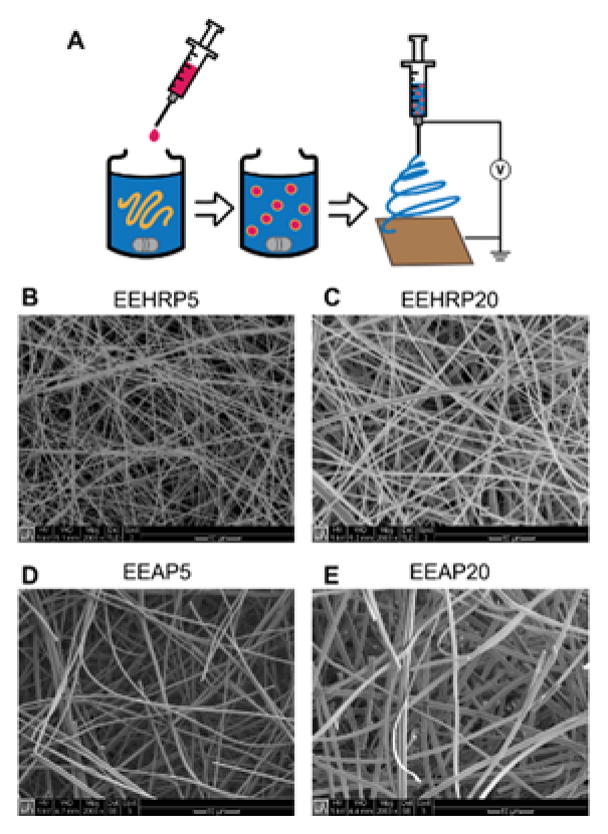

Two model proteins were loaded into Eudragit® L100 fibers through an emulsion electrospinning method using a non-ionic surfactant. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP, ~44 kDa) and alkaline phosphatase (AP, ~160 kDa) were chosen due to their difference in molecular weight, number of subunits, and isoelectric point. In addition, both enzymes are well-characterized and have developed colorimetric activity assays (Azevedo et al., 2003; Millán, 2006). In our studies, HRP and AP also serve as surrogates for more therapeutically-relevant proteins. Emulsion electrospinning with a non-ionic surfactant was utilized to incorporate an aqueous protein solution into an organic polymer solution while reducing exposure of the proteins to the organic solvent interface (Fig. 1A). This strategy has been shown to enhance the bioactivity of the proteins recovered from emulsion electrospun fibers (Briggs and Arinzeh, 2014). The percent aqueous phase in the emulsion (5 and 20 vol%) and the electrospinning flow rate (25 and 40 μL min−1) were varied in each formulation to maximize protein loading and material productivity, respectively (Table 1). All formulations were successful at forming electrospun Eudragit® L100 fibers as confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 1B–E). Fiber diameters were in the range of 300–1300 nm, and were dependent on the molecular weight of protein loaded and the percent aqueous phase. An increase in the protein molecular weight and percent aqueous phase resulted in fibers with slightly larger average diameters. Flow rate did not have a significant effect on fiber diameter for either protein encapsulated. Using this method, proteins were loaded into Eudragit® L100 fibers with very high encapsulation efficiencies, above 95% for all formulations (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Scanning electron microscopy characterization of emulsion electrospun fiber morphology.

A) Schematic of emulsion electrospinning process. B) EEHRP5: HRP loading, 5% aqueous phase. C) EEHRP20: HRP loading, 20% aqueous phase. D) EEAP5: AP loading, 5% aqueous phase. E) EEAP20: AP loading, 20% aqueous phase. All images taken at 2000X magnification.

Table 1. Description and characterization of emulsion electrospun fiber formulations.

Fiber diameters and encapsulation efficiencies are reported as the average of n=3 fiber samples ± standard deviation.

| Formulation Name | Protein Loaded | Protein M.W. (kDa) | Aqueous Phase (%) | Fiber Diameter (nm) | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEHRP5 | HRP | 44 | 5 | 368 ± 101 | 97.21 ± 2.71 |

| EEHRP20 | HRP | 44 | 20 | 617 ± 247 | 96.40 ± 1.03 |

| EEAP5 | AP | 160 | 5 | 578 ± 116 | 94.76 ± 4.05 |

| EEAP20 | AP | 160 | 20 | 1031 ± 289 | 96.19 ± 3.42 |

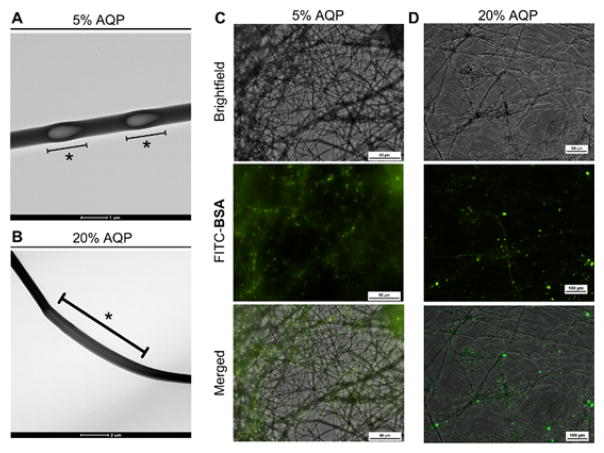

To determine the location of the protein in the nanofibers, we utilized bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a representative non-enzymatic protein with a similar molecular weight to HRP (~66 kDa). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging of the emulsion electrospun fibers revealed sections of aqueous core surrounded by polymer shell for both the 5% (Fig. 2A) and 20% aqueous phase (Fig. 2B) fibers. This core-shell architecture has been observed for emulsion electrospun fibers encapsulating a variety of proteins (Yang et al., 2011, 2008b) and small molecule drugs (Shen et al., 2011). As such, we expect that the fiber architecture observed with the incorporation of BSA is representative for HRP- and AP-loaded emulsion electrospun fibers. Due to the low percentage of the aqueous phase in our emulsions, it is feasible that aqueous emulsion droplets are pulled and elongated in the electric field during the electrospinning process to create discrete protein-loaded aqueous pockets. In fact, upon increasing the aqueous phase from 5% to 20%, we observed more continuous aqueous cores that may reflect the increased aqueous volume relative to the organic/polymer phase or larger aqueous droplets in the emulsion. Loading fibers with FITC-BSA confirmed the presence of protein throughout the nanofibers and showed protein partitioning within the discrete aqueous pockets in the polymeric fiber (Fig. 2C,D), further validating the core-shell structure of the fibers where protein is located within a polymer shell rather than throughout the polymer matrix.

Fig. 2. Core/shell architecture of emulsion electrospun fibers.

Transmission scanning microscopy images of Eudragit® L100/BSA electrospun fibers from A) 5% aqueous phase, scale bar 1 μm, and B) 20% aqueous phase, scale bar 2 μm, emulsions. * indicates the location of an aqueous core. Fluorescence microscopy images of Eudragit® L100/FITC-BSA electrospun fibers from C) a 5% aqueous phase emulsion, scale bar 50 μm and D) a 20% aqueous phase emulsion, scale bar 10 μm.

Maximizing biologic therapeutic loading into biomaterials is important for reducing the total dosing amount, but protein loading is commonly limited by solubility. In emulsion electrospinning, high protein loading can theoretically be achieved by increasing the volume fraction of the protein aqueous phase; however, the ability of solutions to be successfully electrospun into fibers is also limited by this parameter. Thus, we investigated emulsions composed of the maximum aqueous phase percentage without compromising electrospinnability of the solution, which we found to be 20%. Using this emulsion composition, proteins could be loaded into Eudragit-L100 fibers as high as 6.25% (wt/wt), based on the polymer solution weight percent and maximum protein solubility. The electrospinning parameter flow rate has an impact on material manufacturing time and we demonstrated successful protein loading into electrospun fibers at both flow rates tested. The high encapsulation efficiencies achieved (>95%) using this process also demonstrate the manufacturing advantage of this platform for delivery of biotherapeutics, which can be a limitation of other nanotechnology approaches such as particulate systems (Colletier et al., 2002; Marco et al., 2010).

3.2. pH-Controlled Protein Release of Electrospun Eudragit® L100 Fibers

Next, we tested the ability of our protein-loaded Eudragit® L100 fibers to release their protein cargo with pH-dependent kinetics. Such material solubility characteristics are desirable for peroral delivery of proteins, in which fibers can protect proteins from the acidic environment of the stomach while in transit through the gastrointestinal tract. Eudragit® L100 was selected because of its favorable pH-dependent dissolution profile. The carboxyl group of Eudragit® L100 has an apparent pKa of ~6, which causes it to be protonated and insoluble in acidic pH but ionized and soluble in neutral or basic conditions (Nguyen and Fogler, 2005). After peroral administration via swallowing, the material first passes through the stomach (pH 1.5 – 3.5) followed by transit through the intestine, where the pH gradually increases to > 6 (Evans et al., 1988). Thus, Eudragit® L100 fibers can selectively deliver the formulated proteins by means of fiber dissolution in neutral and basic environments. We verified this pH-controlled release of our four main formulations through an experiment mimicking the pH profile encountered and transit time of the material after oral ingestion (Cook et al., 2012), in which the residence time of the material in the oral cavity and esophagus is negligible, although this is known to vary between and within individuals (McConnell et al., 2008). Analysis of protein release from the fiber at 37 °C under mild shaking showed that <5% of the loaded protein was released over 4 hours in acidic conditions (PBS pH 2). In contrast, upon pH increase above 6, fibers released their cargo with burst-release kinetics resulting in ~100% protein release within 1 hour of pH change (Fig. 3A,B). Qualitatively, this burst-release behavior corresponded to fiber dissolution. In PBS pH 2, Eudragit® L100 fiber mats did not dissolve and maintained their macroscopic structure (Fig. 3C) and when the solution pH was increased to 7, fibers dissolved within 1 hour (Fig. 3D). Qualitative observations indicated that time to fiber dissolution was a function of fiber mat thickness, in which thicker fibers mats required longer time to fully wet and dissolve, resulting in delayed release of the protein. Drug release rates from electrospun fibers have been found to be dependent on the rate of water diffusion into the material, which can be affected by a variety of factors including fiber mat thickness, degree of hydrophobicity, and polymer crystallinity (Chou et al., 2015; Han et al., 2013; Jabal et al., 2010; Tipduangta et al., 2016). This correlation of sustained drug release with fiber mat thickness was observed for protein release from EEHRP fibers, in which the variability in release rates observed was due to differences in the thickness of each fiber mat sample.

Fig. 3. pH-controlled release of proteins from Eudragit® L100 nanofibers.

Kinetics of A) HRP and B) AP release from Eudragit® L100 fibers in PBS pH 2 and 7 over 24 hours. Data is representative of results from n=3 fiber punches per formulation and presented as mean ± standard deviation. Qualitative observations of macroscopic fiber mat structure C) intact in PBS pH 2 and D) dissolved upon pH increase to 7.

In our experimental timeframe, we observed that protein release was dependent on fiber dissolution, rather than protein diffusion out of the fiber matrix, as we detected little to no protein released at pH 2 over 4 hours. This observation supports the core-shell structure of the fibers, in which protein is located in the fiber core surrounded by a polymer shell rather than being surface-associated, which would result in a higher rate of protein release in the absence of fiber dissolution. Yang et al. detected between ~3–30% surface-associated protein content for their poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(DL-lactide) (PELA)/lysozyme emulsion electrospun fibers, which they found to be dependent on polymer matrix, inclusion of excipients, and aqueous/organic volume ratio (Yang et al., 2011). The lowest surface-associated protein content was achieved by including a dispersion excipient in the aqueous phase and by decreasing the aqueous/organic ratio. In our system, we observed <5% surface-associated protein content at both 5% and 20% aqueous phases and without including excipients. This characteristic is favorable for controlled-release systems in which non-specific, premature protein delivery is minimized. For peroral delivery, entrapment of the therapeutic within the polymer shell can shield proteins from digestive enzymes in the stomach, such as the protease pepsin. Additionally, high mucus turnover in the intestinal tract poses a challenge to delivery systems by reducing the bioavailable dose due to clearance of the therapeutic during mucus turnover before its absorption (Lai et al., 2009). Finally, some materials-based delivery platforms with sustained release kinetics suffer from incomplete protein release in the time frame from oral ingestion to clearance from the body, further limiting the effective dose that is released at the target site. In contrast, rapid and complete protein release from our fiber delivery system, triggered by a change in pH, can be advantageous for delivery to the intestinal tract by ensuring the full therapeutic dose is released and bioavailable.

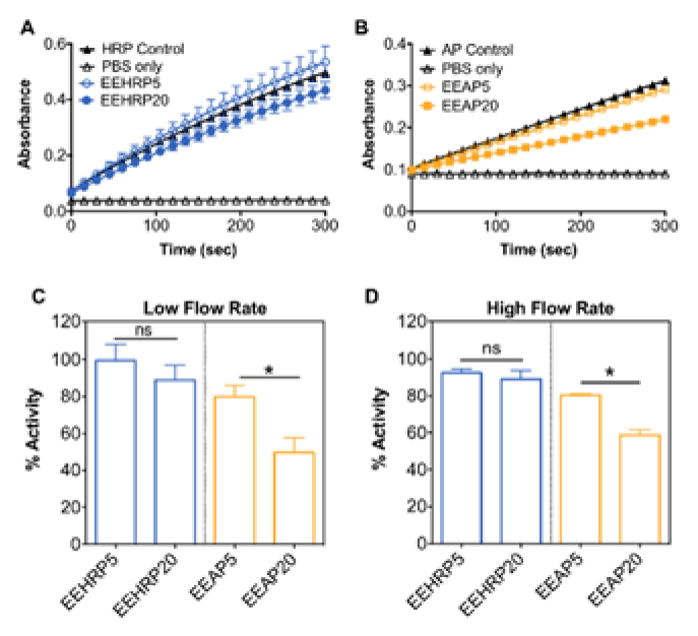

3.3. Bioactivity Retention of Proteins Electrospun in Eudragit® L100 Fibers by Emulsion Electrospinning

Retention of protein bioactivity is important when electrospinning biologics in organic solvents and is currently a major challenge for electrospinning proteins (Ji et al., 2011). We aimed to maximize retention of protein bioactivity after being electrospun into Eudragit® L100 fibers by investigating the effect of flow rate, percent aqueous phase, and incorporation of hydrophilic polymer excipients in the aqueous phase during the emulsion electrospinning process.

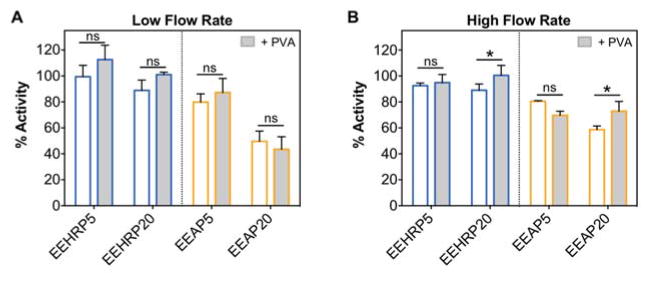

The aqueous phase percentage in the emulsion dictates the maximum loading of the therapeutic of interest since the protein concentration in this phase is limited by its solubility. We hypothesized that increasing the aqueous fraction in the emulsion would result in a higher loss of protein bioactivity due to an increased aqueous/organic interface and protein/solvent interactions. This relationship between percent aqueous phase and protein activity has been observed in other protein-fiber systems (Yang et al., 2011). We utilized colorimetric activity assays to determine the initial rate of substrate conversion of proteins released from the electrospun proteins compared to unformulated protein controls. Representative kinetic activity assay graphs are shown for HRP (Fig. 4A) and AP (Fig. 4B). For HRP-loaded fibers, ~90% enzymatic activity was retained for EEHRP5 and EEHRP20 fibers at each flow rate tested (Fig. 4C,D). There was no significant effect of aqueous phase percentage on HRP bioactivity recovered at either flow rate, nor a significant effect of flow rate with the same formulation. These data conclude that HRP can be electrospun from emulsions with higher aqueous phase percentages and at higher flow rates to increase protein loading and material productivity, respectively, without compromising bioactivity. For AP-loaded fibers we observed a significant decrease in AP bioactivity upon increase of aqueous phase percentage from 5% (EEAP5) to 20% (EEAP20) for both flow rates tested, from ~80% to ~50% (Fig. 4C,D). As was observed with HRP-fibers, there was no significant difference between recovered AP bioactivity of the same formulation at different electrospinning flow rates. Overall, we recovered less bioactivity from AP-loaded fibers than from HRP-loaded fibers, which we hypothesize is due to the larger molecular weight and multimeric structure of AP. In contrast to HRP, an increase of the percent aqueous phase in the emulsion compromised AP activity, which limits the protein loading capacity of the system. However, AP can still be electrospun at higher flow rates to increase productivity without resulting in further activity loss.

Fig. 4. Higher recovery of bioactivity of proteins released from Eudragit® L100 nanofibers prepared from emulsions with lower aqueous phase percentages.

Representative kinetic enzymatic assays of A) HRP and B) AP recovered from electrospun fibers to determine initial velocity kinetics compared to non-electrospun fresh protein controls. Percent bioactivity recovered from HRP- and AP-loaded fibers with different aqueous phases percentages electrospun at C) 25 μL/min (low) and D) 40 μL/min (high) flow rates. Data is representative of results from n=3 fiber punches per formulation and presented as mean ± standard deviation. *p<0.05.

Since we observed loss of protein bioactivity after emulsion electrospinning, we sought to protect the proteins through inclusion of a hydrophilic polymer poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) in the aqueous protein solution. This technique is used to induce the preferential interaction of the protein with the hydrophilic polymer, preventing conformational changes that would otherwise occur through interaction with the organic solvent interface (Ji et al., 2011). For both HRP- and AP-loaded Eudragit® L100 fibers, PVA had no measurable effect on protein bioactivity for the low electrospinning flow rate tested (Fig. 4A). However, when fibers were electrospun at the higher flow rate, inclusion of PVA increased the recovered bioactivity from ~90% to 100% for EEHRP20 and from ~60% to 75% for EEAP20 (Fig. 5B). PVA did not have an effect on 5% aqueous phase fibers at either flow rate. Overall, our results indicate that incorporating PVA is favorable for emulsion electrospinning of proteins from solutions with high aqueous phase percentages, which may be necessary when high protein loading is desired.

Fig. 5. Inclusion of hydrophilic polymer poly(vinyl alcohol) can enhance bioactivity retention from high aqueous phase emulsion formulations electrospun at high flow rates.

Percent bioactivity recovered from HRP- and AP-loaded fibers with or without the inclusion of PVA (1% w/w) in the protein solution electrospun at A) 25 μL/min (low) and B) 40 μL/min (high) flow rates. Data is representative of results from n=3 fiber punches per formulation and presented as mean ± standard deviation. *p<0.05.

There have been few studies investigating the effect of emulsion electrospinning parameters on the bioactivity recovered of proteins released from electrospun fibers. In one study that loaded AP into electrospun polycaprolactone fibers, ~50% activity retention was reported based on an end-point measured absorbance value taken at 1 hour of progression of a colorimetric assay (Ji et al., 2010), which does not account for differences in initial conversion rates. In cases where the enzymatic reaction is substrate-limited, progression to a maximum absorbance value will occur as the substrate is consumed and the reaction rate goes to zero, even if the enzyme is functioning at <100%. This is in contrast to the initial rate of absorbance change over time that was used in our calculations, which discerns changes in enzyme activity based on the rate of product conversion in the initial linear region. Lysozyme is another enzyme commonly used to probe protein loading and bioactivity when formulated into electrospun fibers, and retention values in the range of ~30 – 95% have been reported (Briggs and Arinzeh, 2014; Kim et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011, 2008b). However, these studies all use various polymers, solvents, aqueous phase percentages, and loading amounts. Yang et al. observed that lysozyme bioactivity was dependent on the emulsion aqueous/organic volume ratio, but their study focused on aqueous phases only up to 5% (Yang et al., 2011). The enzyme trypsin has also been electrospun into polycaprolactone fibers and ~66% bioactivity retention was reported after emulsion electrospinning from a 5% aqueous phase emulsion (Pinto et al., 2015). Place et al. loaded the protein fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) into electrospun fibers using the polymer chitosan, comparing emulsion electrospinning with a two-phase electrospinning method (Place et al., 2016). While protein bioactivity was not determined quantitatively, they found that treatment of cells with FGF-2-loaded electrospun fibers resulted in similar cell activity as when cells were treated with soluble FGF-2. Interestingly, this study did not detect any protein that was incorporated into emulsion electrospun fibers by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), in contrast to incorporation of 20% of the total protein input when electrospun by A/O two-phase electrospinning. This measure can be viewed as a surrogate for protein conformation and thus related to protein activity. Their study used similar emulsion electrospinning parameters as in our study (10% aqueous phase, non-ionic surfactant), and the lack of bioactive protein detected from their emulsion electrospun fibers may be due to the differences in polymers and organic solvents used or the inherent instability of growth factor proteins, which have half-lives on the order of minutes (Tessmar and Göpferich, 2007). A study by Peh et al. loaded multiple proteins into poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) emulsion electrospun fibers with a 10% aqueous phase and found that the bioactivity recovered was highly dependent on the protein (Peh et al., 2015), as is supported by the results of our study. Finally, many studies incorporating proteins into electrospun fibers for wound healing and tissue engineering demonstrate function of the encapsulated proteins but bioactivity retention is not quantified due to the non-enzymatic nature of the protein investigated (Briggs et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). While it is difficult draw conclusions from studies evaluating different systems, we demonstrated that protein bioactivity is dependent on aqueous phase percentage in the emulsion as well as on the protein loaded when emulsion electrospinning Eudragit® L100 fibers.

3.4. Evaluation and Extension of Protein-Loaded Fiber Shelf Life

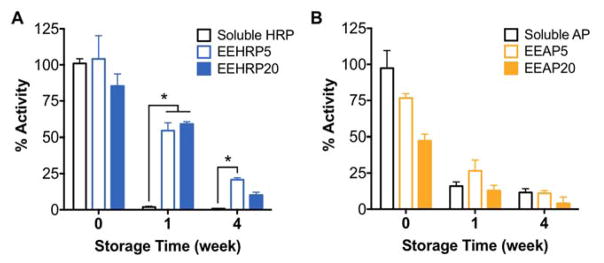

One advantage of delivering therapeutics in fibers is the production of a solid dosage form that is not subject to complications faced by soluble protein storage such as aggregation and hydrolysis. Commonly, protein therapeutics must be used within hours of solubilization and other nanotechnology platforms for protein delivery require fresh production due to low colloidal stability in solution (Frokjaer and Otzen, 2005; Weiss IV et al., 2009). The manufacture of shelf-stable biologics is very desirable and we hypothesized that the incorporation of proteins into electrospun fibers could extend their storage lifetime through enhanced stabilization and protection. We found that storage of HRP in all fiber formulations at room temperature resulted in 30x higher bioactivities recovered after 1 week compared to soluble storage of the protein (Fig. 6A). Recovered bioactivity of HRP was also significantly increased when stored out to 4 weeks in fibers made from 5% (1.5x), but not 20%, aqueous phase emulsions (Fig. 6A). For AP, the benefit of storage in fibers was not observed as bioactivity decay kinetics were similar to that of AP storage in aqueous solution (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6. Stability of proteins is enhanced or maintained by formulation into electrospun fibers.

Kinetics of activity decay of A) HRP and B) AP recovered from electrospun fibers after storage at room temperature for 1 and 4 weeks compared to storage in aqueous solution (soluble). Data is representative of results from n=3 fiber punches per formulation and presented as mean ± standard deviation. *p<0.05.

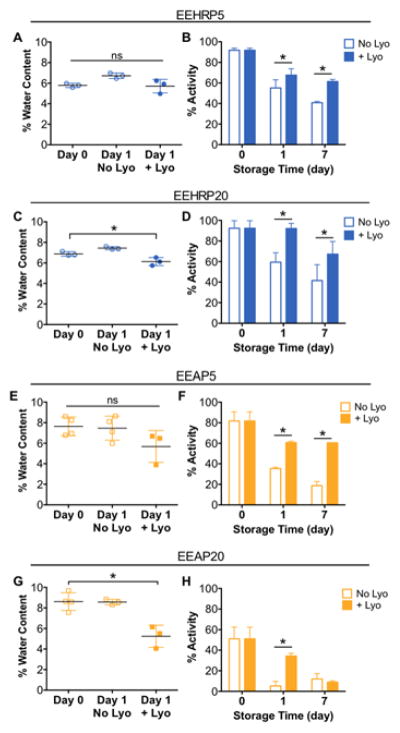

To further extend the shelf life of these protein loaded-fibers, we investigated the contribution of residual water in the fibers. We hypothesized that any remaining water in the aqueous pockets of the fiber could result in increased mobility of the protein and thus increase the probability of conformational change and activity loss (Chi et al., 2003). Water content of protein-loaded fibers was measured immediately after electrospinning and after one day of storage at room temperature or under lyophilization. For HRP- and AP-fibers produced from 5% aqueous phase emulsions, there was no significant difference in fiber water content before and after lyophilization (Fig. 7A,E). However, lyophilization was found to significantly decrease the water content of 20% aqueous phase HRP- and AP-fibers by 10% and 40%, respectively (Fig. 7C,G). We then investigated the effect of lyophilization on protein bioactivity retention and if the decrease in water content observed upon lyophilization could prevent rapid bioactivity loss of the encapsulated proteins. After 1 day of lyophilization, all protein loaded-fibers retained significantly higher bioactivity than their non-lyophilized counterparts for all formulations (Fig. 7B,D,F,H). Lyophilization resulted in bioactivities 1.2x, 1.5x, 1.7x, and 6.6x higher for EEHRP5, EEHRP20, EEAP5, and EEAP20 fibers, respectively. These results also indicated that our lyophilization procedure did not have a detrimental effect on protein structure, which would have resulted in a greater activity loss for lyophilized samples. After overnight lyophilization, fibers were removed from vacuum and stored at room temperature with non-lyophilized fibers. After 7 days, we also observed that lyophilization significantly increased the bioactivity recovered from the encapsulated proteins for all formulations except EEAP20. The recovered protein bioactivity after 7 days was 1.5x, 1.6x, and 3.2x higher for lyophilized EEHRP5, EEHRP20, and EEAP5 fibers, respectively, compared to their storage without one-time lyophilization. This resulted in greater than 60% recovery of initial protein bioactivity for those formulations.

Fig. 7. Lyophilization of protein-loaded fibers can reduce water content and significantly extend protein bioactivity retention during storage.

Water content of protein-loaded fibers immediately after electrospinning, one day after electrospinning stored at room temperature, and one day after electrospinning stored under lyophilization of electrospun fibers A) EEHRP5, C) EEHRP20, E) EEAP5, and G) EEAP20. After lyophilization overnight, fibers were stored in the same conditions as the non-lyophilized fibers at room temperature for a total storage time of 7 days. Bioactivity of proteins recovered from electrospun fibers B) EEHRP5, D) EEHRP20, F) EEAP5, and H) EEAP20 with or without overnight lyophilization over 7 days. Data is representative of results from n=3 fiber punches per formulation and presented as mean ± standard deviation. *p<0.05.

Commonly, proteins are stored in lyophilized form rather than in solution to prevent protein hydrolysis and loss of active conformation. To compare storage of proteins in electrospun fibers to this conventional storage method, we evaluated the decay in protein activity following storage at 37 °C as a lyophilized solid (as provided by the supplier). Additionally, we were interested in the potential of the electrospinning platform to store therapeutic proteins long term, both in emulsion electrospun fibers and in hydrophilic fibers. Thus, we also characterized protein shelf-life when formulated in PVA nanofibers spun from aqueous blend solutions, both with and without lyophilization. This comparison also allowed us to determine the impact of emulsion electrospinning specifically on protein stability. We found that lyophilized AP protein lost ~20% activity after 1 week and ~30% after 3 weeks of storage (Fig. S1). Loss of bioactivity was accelerated when proteins were electrospun into PVA nanofibers, but this activity loss was completely prevented through fiber lyophilization, as was observed for proteins formulated in emulsion electrospun fibers (Fig. S1). Lyophilization of protein-loaded PVA fibers achieved equivalent levels of protein activity as storage of protein in lyophilized form through the time points investigated in our study (Fig. S1). These observations suggest two main sources contribute to protein deactivation when formulated in emulsion electrospun fibers. First, the emulsion electrospinning process, compared to electrospinning aqueous solutions, results in an initial loss of protein function, likely due to protein exposure to organic solvents during formulation. Second, residual water in the nanomaterials, present in fibers electrospun both from emulsions and aqueous solutions, result in a reduced protein conformational stability, causing further loss of bioactivity. In this work, we have identified methods to overcome both phases of protein activity loss through reduction of the emulsion aqueous phase percentage and use of hydrophilic polymer excipients, and removal of residual water in the material with lyophilization, respectively.

While published data on the shelf life of proteins in electrospun fibers is limited, a study by Pinto et al. observed ~60% and ~40% bioactivity was retained by proteins released from non-lyophilized fibers after 2 and 4 weeks, respectively (Pinto et al., 2015). This activity decay profile was similar to that observed for our non-lyophilized HRP protein formulations. Despite the similarity in activity loss kinetics, it is important to note that the referenced study used a different polymer (polycaprolactone), protein (trypsin), and a 5% aqueous phase emulsion. Thus, further work is required to fully characterize the stability of additional biotherapeutics in electrospun nanomaterials. Lyophilization of proteins in paper-based networks is highly utilized in microfluidic devices, in which dry storage of proteins is advantageous to enhance stability over long-term storage of the device (Ramachandran et al., 2014). Results from our study support the application of this technique used in paper-based microfluidics to extending protein storage in polymeric nanofibers. Overall, we can conclude that lyophilization of protein-loaded electrospun fibers results in more shelf-stable biologic formulations, and we have shown that this technique can extend the lifetime of both HRP and AP for at least 7 days at room temperature for emulsion electrospun fibers and for at least 17 days at 40°C for hydrophilic electrospun fibers. Importantly, we observed equivalent stability of proteins stored as lyophilized powder and in lyophilized hydrophilic nanofibers. This storage method involves only a one-time lyophilization step, reducing the need for costly equipment and power, and may eliminate the need for refrigeration to maintain protein stability over this time frame. Thus, this is an attractive strategy for protein stabilization and storage, which is a major problem for polymeric-based protein delivery systems and bioactive scaffolds for tissue engineering.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, two model proteins, horseradish peroxidase and alkaline phosphatase, were loaded into Eudragit® L100 fibers using an emulsion electrospinning technique. We investigated the emulsion parameters of aqueous phase percentage and inclusion of a hydrophilic polymer and the electrospinning parameter of flow rate to optimize protein loading and bioactivity. Using this optimized method, both proteins were loaded into fibers at high efficiencies and were released in a pH-controlled manner with minimal non-specific protein release. We identified that bioactivity retention of the proteins could be enhanced through decreasing the aqueous phase percentage in the emulsion and including a hydrophilic polymer with the protein. Flow rate during electrospinning was not observed to have an effect on protein bioactivity, demonstrating that the electrospinning process was not detrimental to protein structure and that material productivity can be increased without compromising therapeutic activity for future manufacturing scale-up. Protein stability in emulsion electrospun fibers was found to be dependent on the protein loaded both during electrospinning and upon storage. HRP stability over 4 weeks was enhanced through fiber formulation while the formulation type (in fibers vs. in solution) had no effect on AP stability. For both proteins, a one-time lyophilization of emulsion electrospun fibers significantly extended the shelf life of the product over 7 days when stored at room temperature. Thus, protein-loaded Eudragit® L100 fibers are a promising new biotechnology platform for peroral protein delivery to overcome the challenge of the harsh gastric environment, which is a critical first step when developing new dosage forms for this administration route.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kevin Liu for assistance with SEM imaging and Hangyu Zhang for assistance with TEM imaging. Part of this work was conducted at the Molecular Analysis Facility, a National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure site at the University of Washington which is supported in part by the National Science Foundation (grant ECC-1542101), the University of Washington, the Molecular Engineering & Sciences Institute, the Clean Energy Institute, and the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by NIH grant HD075703 and AI112002 to K.A.W. H.F. acknowledges additional financial support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE-1256082) and the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agarwal S, Wendorff JH, Greiner A. Use of electrospinning technique for biomedical applications. Polymer (Guildf) 2008;49:5603–5621. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar LE, Unnithan AR, Amarjargal A, Tiwari AP, Hong ST, Park CH, Kim CS. Electrospun polyurethane/Eudragit® L100-55 composite mats for the pH dependent release of paclitaxel on duodenal stent cover application. Int J Pharm. 2015;478:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo AM, Martins VC, Prazeres DMF, Vojinović V, Cabral JMS, Fonseca LP. Horseradish peroxidase: A valuable tool in biotechnology. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2003;9:199–247. doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(03)09003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs T, Arinzeh TL. Examining the formulation of emulsion electrospinning for improving the release of bioactive proteins from electrospun fibers. J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2014;102:674–684. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs T, Matos J, Collins G, Arinzeh TL. Evaluating protein incorporation and release in electrospun composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2015;103:3117–3127. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni G, Maggi L, Tammaro L, Canobbio A, Di Lorenzo R, D’Aniello S, Domenighini C, Berbenni V, Milanese C, Marini A. Fabrication, Physico-Chemical, and Pharmaceutical Characterization of Budesonide-Loaded Electrospun Fibers for Drug Targeting to the Colon. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104:3798–3803. doi: 10.1002/jps.24587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi EY, Krishnan S, Randolph TW, Carpenter JF. Physical stability of proteins in aqueous solution: Mechanism and driving forces in nonnative protein aggregation. Pharm Res. 2003;20:1325–1336. doi: 10.1023/A:1025771421906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Han SH, Hyun C, Yoo HS. Buccal adhesive nanofibers containing human growth hormone for oral mucositis. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2015;104:1396–1406. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SF, Carson D, Woodrow KA. Current strategies for sustaining drug release from electrospun nanofibers. J Control Release. 2015;220:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colletier JP, Chaize B, Winterhalter M, Fournier D. Protein encapsulation in liposomes: efficiency depends on interactions between protein and phospholipid bilayer. BMC Biotechnol. 2002;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MT, Tzortzis G, Charalampopoulos D, Khutoryanskiy VV. Microencapsulation of probiotics for gastrointestinal delivery. J Control Release. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date AA. Nanoparticles for oral delivery: Design, evaluation and state-of-the-art. J Control Release. 2016;240:504–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davitt CJH, Lavelle EC. Delivery strategies to enhance oral vaccination against enteric infections. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DF, Pye G, Bramley R, Clark AG, Dyson TJ, Hardcastle JD. Measurement of gastrointestinal pH profiles in normal ambulant human subjects. Gut. 1988;29:1035–1041. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.8.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer S, Otzen DE. Protein drug stability: a formulation challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrd1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M, Gomez-Orellana I. Challenges for the oral delivery of macromolecules. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:289–95. doi: 10.1038/nrd1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Jain A, Chakraborty M, Sahni JK, Ali J, Dang S. Oral delivery of therapeutic proteins and peptides: a review on recent developments. Drug Deliv. 2013;20:237–246. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2013.819611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamori M, Yoshimatsu S, Hukuchi Y, Shimizu Y, Fukushima K, Sugioka N, Nishimura A, Shibata N. Preparation and pharmaceutical evaluation of nano-fiber matrix supported drug delivery system using the solvent-based electrospinning method. Int J Pharm. 2014;464:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han N, Bradley PA, Johnson J, Parikh KS, Hissong A, Calhoun MA, Lannutti JJ, Winter JO. Effects of hydrophobicity and mat thickness on release from hydrogel-electrospun fiber mat composites. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2013;24:2018–2030. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2013.822246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Tian L, Prabhakaran MP, Ding X, Ramakrishna S. Fabrication of nerve growth factor encapsulated aligned poly(ε-caprolactone) nanofibers and their assessment as a potential neural tissue engineering scaffold. Polymers (Basel) 2016;8:54. doi: 10.3390/polym8020054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Liu S, Zhou G, Huang Y, Xie Z, Jing X. Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for drug delivery applications. J Control Release. 2014;185:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilan Y. Oral immune therapy: targeting the systemic immune system via the gut immune system for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Transl Immunol. 2016;5:e60. doi: 10.1038/cti.2015.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabal JMF, McGarry L, Sobczyk A, Aston DE. Substrate effects on the wettability of electrospun titania- poly(vinylpyrrolidone) fiber mats. Langmuir. 2010;26:13550–13555. doi: 10.1021/la1017399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Sun Y, Yang F, Van Den Beucken JJJP, Fan M, Chen Z, Jansen JA. Bioactive electrospun scaffolds delivering growth factors and genes for tissue engineering applications. Pharm Res. 2011;28:1259–1272. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Yang F, Van Den Beucken JJJP, Bian Z, Fan M, Chen Z, Jansen JA. Fibrous scaffolds loaded with protein prepared by blend or coaxial electrospinning. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4199–4207. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Yu DG, Wang X, Geraldes CFGC, Williams GR, Bligh SWA. Electrospun Contrast-Agent-Loaded Fibers for Colon-Targeted MRI. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:977–985. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TG, Lee DS, Park TG. Controlled protein release from electrospun biodegradable fiber mesh composed of poly(ε-caprolactone) and poly(ethylene oxide) Int J Pharm. 2007;338:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai SK, Wang YY, Hanes J. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:158–171. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MM, Dougan G. Optimism over vaccines administered via mucosal surfaces. Lancet. 1998;351:1375–1376. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Su Y, Liu S, Tan L, Mo X, Ramakrishna S. Encapsulation of proteins in poly(l-lactide-co-caprolactone) fibers by emulsion electrospinning. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2010;75:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco M, Shamsuddin S, Razak KA, Aziz AA, Devaux C, Borghi E, Levy L, Sadun C. Overview of the main methods used to combine proteins with nanosystems: Absorption, bioconjugation, and encapsulation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2010;5:37–49. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell EL, Fadda HM, Basit AW. Gut instincts: Explorations in intestinal physiology and drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millán JL. Alkaline Phosphatases: Structure, substrate specificity and functional relatedness to other members of a large superfamily of enzymes. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:335–41. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitragotri S, Burke PA, Langer R. Overcoming the challenges in administering biopharmaceuticals: formulation and delivery strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:655–72. doi: 10.1038/nrd4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DA, Fogler HS. Facilitated diffusion in the dissolution of carboxylic polymers. AIChE J. 2005;51:415–425. doi: 10.1002/aic.10329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar VK, Meher JG, Singh Y, Chaurasia M, Surendar Reddy B, Chourasia MK. Targeting of gastrointestinal tract for amended delivery of protein/peptide therapeutics: Strategies and industrial perspectives. J Control Release. 2014;196:168–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peh P, Lim NSJ, Blocki A, Chee SML, Park HC, Liao S, Chan C, Raghunath M. Simultaneous Delivery of Highly Diverse Bioactive Compounds from Blend Electrospun Fibers for Skin Wound Healing. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:1348–1358. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto SC, Rodrigues AR, Saraiva JA, Lopes-da-Silva JA. Catalytic activity of trypsin entrapped in electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) nanofibers. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2015;79:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place LW, Sekyi M, Taussig J, Kipper MJ. Two-Phase Electrospinning to Incorporate Polyelectrolyte Complexes and Growth Factors into Electrospun Chitosan Nanofibers. Macromol Biosci. 2016;16:371–380. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201500288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Fu E, Lutz B, Yager P. Long-term dry storage of an enzyme-based reagent system for ELISA in point-of-care devices. Analyst. 2014;139:1456–62. doi: 10.1039/c3an02296j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reneker DH, Chun I. Nanometre diameter fibres of polymer, produced by electrospinning. Nanotechnology. 1996;7:216–223. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/7/3/009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders EH, Kloefkorn R, Bowlin GL, Simpson DG, Wnek GE. Two-phase electrospinning from a single electrified jet: Microencapsulation of aqueous reservoirs in poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) fibers. Macromolecules. 2003;36:3803–3805. doi: 10.1021/ma021771l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shastri VP, Sy JC, Klemm AS. Emulsion as a means of controlling electrospinning of polymers. Adv Mater. 2009;21:1814–1819. doi: 10.1002/adma.200701630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Yu D, Zhu L, Branford-White C, White K, Chatterton NP. Electrospun diclofenac sodium loaded Eudragit® L 100-55 nanofibers for colon-targeted drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2011;408:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sill TJ, von Recum Ha. Electrospinning: Applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1989–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessmar JK, Göpferich AM. Matrices and scaffolds for protein delivery in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:274–291. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipduangta P, Belton P, Fábián L, Wang LY, Tang H, Eddleston M, Qi S. Electrospun Polymer Blend Nanofibers for Tunable Drug Delivery: The Role of Transformative Phase Separation on Controlling the Release Rate. Mol Pharm. 2016;13:25–39. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Qian Y, Li L, Pan L, Njunge LW, Dong L, Yang L. Evaluation of emulsion electrospun polycaprolactone/hyaluronan/epidermal growth factor nanofibrous scaffolds for wound healing. J Biomater Appl. 2015;30:1–13. doi: 10.1177/0885328215586907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss WF, IV, Young TM, Roberts CJ. Principles, approaches, and challenges for predicting Protein Aggregation Rates and Shelf Life. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:1246–1277. doi: 10.1002/jps.21521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Li X, Cui W, Zhou S, Tan R, Wang C. Structural stability and release profiles of proteins from core-shell poly (DL-lactide) ultrafine fibers prepared by emulsion electrospinning. J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2008a;86:374–385. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Li X, He S, Cheng L, Chen F, Zhou S, Weng J. Biodegradable ultrafine fibers with core-sheath structures for protein delivery and its optimization. Polym Adv Technol. 2011;22:1842–1850. doi: 10.1002/pat.1681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Li X, Qi M, Zhou S, Weng J. Release pattern and structural integrity of lysozyme encapsulated in core-sheath structured poly(dl-lactide) ultrafine fibers prepared by emulsion electrospinning. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008b;69:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarin AL. Coaxial electrospinning and emulsion electrospinning of core-shell fibers. Polym Adv Technol. 2011;22:310–317. doi: 10.1002/pat.1781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yarin AL, Koombhongse S, Reneker DH. Taylor cone and jetting from liquid droplets in electrospinning of nanofibers. J Appl Phys. 2001;90:4836–4846. doi: 10.1063/1.1408260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Wu J, Shi J, Farokhzad OC. Nanotechnology for protein delivery: Overview and perspectives. J Control Release. 2016;240:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.