Abstract

Pharmacological activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid derived 2-like 2 (NRF2), the key regulator of the cellular antioxidant response, has been recognized as a feasible strategy to reduce oxidative/electrophilic stress and prevent carcinogenesis or other chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease. In contrast, due to the discovery of the “dark side” of NRF2, where prolonged activation of NRF2 causes tissue damage, cancer progression, or chemoresistance, efforts have been devoted to identify inhibitors. Currently, only one NRF2 activator has been approved for use in the clinic, while no specific NRF2 inhibitors have been discovered. Future development of NRF2-targeted therapeutics should be based on our current understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of this protein. In addition to the KEAP1-dependent mechanisms, the recent discovery of other pathways involved in the degradation of NRF2 have opened up new possibilities for the development of safe and specific therapeutics. Here, we review available and putative NRF2-targeted therapeutics and discuss their modes of action as well as their potential for disease prevention and treatment.

Keywords: autophagy, cancer, chemoprevention, diabetes, electrophiles, NRF2

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Nuclear factor-erythroid derived 2-like 2 (NRF2) is a crucial regulator of the cellular antioxidant response. NRF2 is a transcription factor that accumulates following oxidative/electrophilic modification of a key cysteine residue (C151) in its negative regulator, Kelch-like ECH associated protein 1 (KEAP1). KEAP1 is comprised of different functional domains: a broad complex, tram-track, bric-à-brac homodimerization (BTB) domain, an intervening region (IVR), and a C-terminal Kelch domain responsible for NRF2 binding [1]. KEAP1 interacts through its Kelch domain with the DLG and ETGE motifs in the NRF2-ECH homology 2 (Neh2) domain of NRF2 [2]. The Neh2 domain also contains seven lysine residues that are ubiquitylated by the KEAP1-Cullin 3-Ring Box Protein 1 (KEAP1-CUL3-RBX1) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, targeting NRF2 for degradation by the 26S proteasome [2]. Disruption of KEAP1-dependent degradation of NRF2 results in its accumulation and translocation to the nucleus, where it heterodimerizes with small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (sMAF) proteins and binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) of target genes to activate their transcription [3]. This mechanism of controlled NRF2 regulation is termed “canonical activation”, as oxidative/electrophilic modification of KEAP1 results in the activation of NRF2 targets that mitigate oxidative/electrophilic damage and restore cellular homeostasis. Importantly, NRF2 can be activated with low doses of electrophiles known as chemopreventive compounds, which induce the expression of NRF2 target genes to protect cells from endogenous and exogenous insults that cause diseases [4].

Other mechanisms of NRF2 regulation that are KEAP1 cysteine-independent have been recently discovered. Our lab and others have demonstrated that alterations in the autophagy lysosomal pathway, a key cellular degradation pathway, can also lead to NRF2 activation [5–7]. The adaptor protein and autophagic substrate p62/SQSTM1, interacts with KEAP1 through its KEAP1-interacting region (KIR), which contains an STGE motif similar to the ETGE motif in NRF2, thus sequestering KEAP1 in autophagosomes and activating NRF2 [6, 8]. Regulation of NRF2 via the p62-KEAP1 interaction is termed “non-canonical activation” as it occurs independently of oxidative modifications to KEAP1. Furthermore, there are also KEAP1-independent NRF2 regulators, such as β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), which upon phosphorylation of the DSGIS and DSAPGS motifs in the Neh6 domain of NRF2 by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) facilitates the SKP1-CUL1-F box protein (SCF)-mediated ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of NRF2 [9–11]. Most recently we identified synoviolin (SYVN1 or HRD1), a single unit endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane E3 ubiquitin ligase, as another negative regulator of NRF2 [12]. As a result, the discovery of these new regulatory mechanisms expanded not only our understanding of the NRF2 pathway but also added possible therapeutic targets. In this article, we will discuss the current state and the future of NRF2-targeted therapeutics based on our present understanding of NRF2 pathway components and modes of regulation (Figure 1), and their potential for disease prevention and treatment.

Figure 1. NRF2-targeted therapeutics.

NRF2 can be activated by targeting the proteins that promote its degradation, such as KEAP1-CUL3-RBX1, GSK3-SCF-β-TrCP, and HRD1, or by targeting p62, which sequesters KEAP1 into autophagosomes. The different classes of NRF2 activators available to date are represented. Conversely, NRF2 could possibly be inhibited by targeting the NRF2-sMAF protein complex. No specific NRF2 inhibitor classes have been identified yet.

NRF2-based therapeutics

It has been almost forty years since the field of chemoprevention was inaugurated with the studies of Lee Wattenberg and Paul Talalay, who identified that phenolic antioxidants used as food additives prevented chemical carcinogenesis in mouse models by upregulating enzymes involved in the metabolism and disposition of those chemicals [13, 14]. It was later defined that most of these compounds activated the NRF2 pathway, and the race to discover and characterize NRF2-dependent chemopreventive compounds started. Since then, only canonical NRF2 activators— sulforaphane (SF), bardoxolone methyl (CDDO-Me), RTA 408, and dimethyl fumarate (DMF, Tecfidera)—have entered clinical trials in the USA (clinicaltrials.gov), and only DMF has been FDA-approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (Table 1) [15–18]. This therapeutic deficit has drawn attention to some key aspects that are defining current and future investigations for the development of NRF2-targeted drugs.

Table 1. NRF2-targeted therapeutics.

Select examples of each class of NRF2-targeted therapeutic.

| Therapeutics | Mechanism of action | Molecules | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Electrophilic NRF2 activators | Natural products | Electrophilic modification of KEAP1-C151 | Sulforaphane

|

[15] |

| Bixin |

[20] | |||

|

| ||||

| Natural product- derived | Electrophilic modification of KEAP1-C151 | Dimethyl fumarate

|

[17] | |

Bardoxolone methyl (CDDO-Me)

|

[16] | |||

|

| ||||

| Pro-electrophilic NRF2 activators | Natural products | Electrophilic modification of KEAP1-C151 | Carnosic acid

|

[22] |

Carnosol

|

[22] | |||

|

| ||||

| Non-electrophilic compounds | Peptides | Binding to KEAP1 Kelch domain | Ac-DPETGEL-OH (7mer) | [23] |

| FITC-β-DEETGEF-OH (7mer) | [23] | |||

| FITC-LDEETGEFL-NH2 (9mer) | [23] | |||

| FAM-LDEETGELP-OH (9mer) | [23] | |||

|

| ||||

| Small molecules | Binding to KEAP1 Kelch domain | Compound 2

|

[26] | |

Cpd 15

|

[27] | |||

Cpd 16

|

[27] | |||

(SRS)-5

|

[28] | |||

| AN-465/144580 |

[29] | |||

|

| ||||

| KEAP1-independent NRF2 activators | Natural product | GSK-3 inhibition | Nordihydroguaiaretic acid

|

[31] |

|

| ||||

| Synthetic | HRD1 inhibition | LS-102

|

[12] | |

|

| ||||

| NRF2 inhibitors | Natural product | Global protein translation inhibitor | Brusatol

|

[47] |

Ac: acetyl, FITC: fluoresceine isothiocyanate, FAM: carboxyfluoresceine.

Electrophilic NRF2 activators

This was the first superclass of NRF2 activators that was discovered since electrophiles react with C151 in KEAP1 and result in canonical NRF2 activation (Figure 1). However, it was recognized very early on that due to their chemical nature these were not specific activators, since they could react with cysteines in other proteins and therefore, alter multiple signaling pathways. In addition, electrophiles interact with glutathione (GSH), which limits their half-life (since they are inactivated and excreted), and thus can potentially cause GSH depletion and redox imbalance. These toxic effects imply that electrophilic NRF2 activators have a very small therapeutic window, since their positive effects are limited to low doses. Nevertheless, discovery and characterization of these compounds has not been discouraged in the field for the following reasons. First, electrophilic NRF2 activators still constitute valuable research tools to understand the mechanisms of NRF2 regulation. The isothiocyanate SF remains the most widely studied and classic example of an NRF2 activator. Its use in vitro, in vivo, and in clinical trials has been fundamental to our understanding of the NRF2-KEAP1 pathway. Second, many electrophilic NRF2 activators are obtained from natural products, mainly non-nutrient phytochemicals, thus making them available to large populations at a low cost. Dietary supplementation with spices such as turmeric, cinnamon, and bixin (Table 1), as well as the inclusion of whole foods such as green tea, broccoli sprouts and other cruciferous vegetables ensure constant exposure that cannot always be achieved with drugs due to low treatment adherence [4, 19, 20]. Third, the structure of electrophilic NRF2 activators may be chemically modified to increase their safety and specificity. For example, structure activity relationship (SAR) studies have been performed to alter the electrophilicity of SF and CDDO. However, reduced electrophilicity limits toxicity but also decreases activity and potency [21]. Finally, the pleiotropic effects of many electrophilic NRF2 activators bring additional health benefits by modulating other signaling pathways, such as inflammation and apoptosis. This further supports the consumption of whole foods containing multiple chemopreventive compounds that would potentially have additive effects in their ability to activate NRF2 and other pathways [15].

Recently, it has been speculated that pro-electrophilic drugs (PEDs) may be an effective strategy to bypass toxicity and target-organ selectivity problems of electrophilic compounds. PEDs are pro-drugs, inactive and harmless unless they are converted to their active form [22]. Certain hydroquinones, such as carnosic acid and carnosol (Table 1), are converted into electrophilic quinones upon oxidation [22]. Ideally, pro-drug conversion would only take place in organs under oxidative stress, where GSH would already be depleted leading to increased selectivity for KEAP1-C151. The identification and development of PEDs could constitute a new research and therapeutic avenue for canonical activators; however, extensive proteomic studies should be performed to identify all the protein targets modified by metabolites of PEDs to foresee off-target effects and toxicities.

Non-electrophilic NRF2 activators

In addition to electrophilic modifiers of KEAP1, current efforts are underway to identify targeted, non-electrophilic activators of NRF2 (Figure 1). Since there are no known allosteric sites or an active site for the regulation of NRF2 or KEAP1, a likely target for the development of NRF2 activators lies at the interference of protein-protein interactions (PPI). The PPIs that could be disrupted are: (A) the Kelch-DLG/ETGE interfase, (B) KEAP1 homodimers (at the BTB domain), and (C) the KEAP1-CUL3 binding region. Disruption of PPI could be achieved by either covalent or non-covalent mechanisms. The enthusiasm for covalent molecules is low; due to their irreversible nature these agents could cause prolonged NRF2 activation (the “dark side” of NRF2). Therefore, efforts have been focused on the development of non-covalent, non-electrophilic NRF2 activators, which encompass both peptides and small molecules. Peptides that mimic the high-affinity ETGE domain and compete with NRF2 for KEAP1 binding have been developed (Table 1) [23]. Interestingly, studies have determined that peptides 7 to 16 amino acids long can bind the Kelch domain, but their activity in cells is very limited [24]. While peptides are predicted to have high specificity and proof-of-concept has been derived from the identification of proteins with E/STGE motifs that bind the Kelch domain and activate NRF2 (e.g., p62), their development as therapeutic agents faces various challenges. Peptides are not orally available, are chemically unstable, do not enter cells easily, and may be prone to aggregation [25]. Consequently, the development of small molecule PPI inhibitors has garnered the most attention.

Very recently, several small molecules that bind the Kelch domain with very high affinities have been developed (Figure 1, Table 1). A good example is “compound 2”, currently the most potent inhibitor of KEAP1-NRF2 binding, which binds to the Kelch domain [26]. Other small molecule PPI inhibitors previously described are Cpd15 and Cpd16 [27], (SRS)-5 [28], and AN-465/144580 [29], among others. These compounds are not very efficient in vivo due to poor cell permeability, so their chemical properties still need to be fine-tuned to make them more drug-like, but promising lead compounds have been developed. It will be interesting to see how other signaling pathways are also modulated by these small molecules due to the interaction of KEAP1 with other E/STGE motif-containing proteins, such as p62, PGAM5, WTX, and prothymosin-α, to name a few [30]. While the BTB domain of KEAP1 may not be an ideal target, since this domain is more conserved, the BTB/IVR region that interacts with CUL3 could be a more suitable target. However, it might be challenging to identify a small molecule that would disrupt PPI that does not fit into a groove or pocket-like structure.

KEAP1-independent NRF2 activators

The KEAP1-CUL3 E3 ubiquitin ligase is the main mode of NRF2 regulation; however, the β-TrCP-SCF complex has emerged as another important negative regulator of NRF2, offering more possibilities for pharmacological development (Figure 1). The natural chemopreventive compound nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) (Table 1) activates NRF2 by inhibiting Neh6 phosphorylation, but it also activates multiple signaling pathways [31]. Another possible therapeutic target could be inhibiting the recognition of the Neh6 phosphodegron in NRF2 by β-TrCP. β-TrCP is an F-box protein that contains WD40 repeats in its substrate recognition region, and the discovery of a small molecule that binds to WD40 repeats in the yeast SCF complex serves as proof-of-concept [32, 33]. A caveat of this approach would be that the β-TrCP-SCF complex has many known substrates, so a WD40-binding compound could have many off-target effects. Furthermore, it should be critically assessed under what physiopathological settings NRF2 is regulated by the β-TrCP-SCF complex.

Our lab recently discovered that in liver cirrhosis cells under ER stress, activation of the IRE1-XBP1 arm degrades NRF2 in a HRD1-dependent manner (Figure 1) [12]. The IRE1 inhibitor 4μ8C and the HRD1 inhibitor LS-102 (Table 1) can restore NRF2 protein level and activity in a CCl4-induced liver cirrhosis mouse model, thus restoring liver function [12]. It remains to be elucidated under which other pathological settings this HRD1-dependent NRF2 regulation is predominant to exploit this niche for new drug development.

p62-dependent NRF2 activation

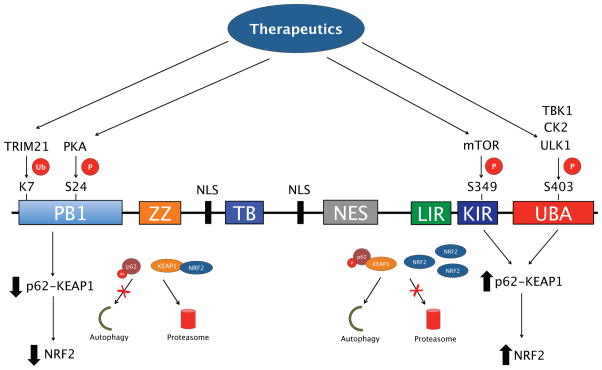

As mentioned above, the non-canonical NRF2 pathway is mediated by the interaction between p62 and KEAP1. While blockage of autophagy leads to the p62-dependent sequestration of KEAP1 into protein aggregates to activate NRF2, a number of post-translational modifications of p62 have also been shown to upregulate NRF2 by altering the p62-KEAP1 interaction (Figure 2). For example, phosphorylation of S349 in the STGE motif of p62 by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) increases its affinity for KEAP1, enhancing the degradation of the phospho-p62-KEAP1 complex by autophagy, resulting in NRF2 activation [34]. Alternatively, ubiquitylation of K7 in the PB1 domain of p62 by tripartite motif-containing protein 21 (TRIM21) inhibits the p62-KEAP1 interaction, with genetic ablation of TRIM21 enhancing NRF2-based signaling and reducing cellular toxicity during increased oxidative stress [35]. Other post-translational modifications that could alter the p62-KEAP1 interaction to upregulate NRF2 include phosphorylation of S24 in the PB1 domain of p62, which regulates the oligomerization and interaction of p62 with its binding partners [36], as well as phosphorylation of S403 in the UBA domain by unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1), casein kinase 2 (CK2) or tank-binding protein kinase 1 (TBK1), which enhances autophagic degradation of p62 and its ubiquitylated cargo [37–39]. These results suggest that targeting the enzymes that regulate the post-translational modifications of p62, such as mTOR or TRIM21 could be used to alter the p62-KEAP1 interaction, and thus provide novel p62-based NRF2 therapeutics (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Post-translational modification of key p62 domains affects NRF2 activation.

p62/SQSTM1 consists of an N-terminal Phox and Bem1 (PB1) domain, a ZZ-type zinc finger domain, a Traf6 binding (TB) domain, two nuclear localization sequences (NLS), a nuclear export signal (NES), an LC3-interacting region (LIR), a KEAP1-interacting region (KIR), and a C-terminal ubiquitin association domain (UBA). The PB1 domain can be phosphorylated at S24 by PKA and ubiquitylated at K7 by tripartite TRIM21 to prevent p62 oligomerization and sequestration of target proteins, including KEAP1, which results in NRF2 being degraded by the proteasome. Phosphorylation of S349 in the KIR by mTOR and S403 in the UBA domain by ULK1, CK2 or TBK1, enhances p62-KEAP1 binding, resulting in upregulation of NRF2. Therefore, the enzymes that modify p62 could be potential targets for p62-based NRF2 therapeutics.

Rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, could possibly upregulate the autophagic degradation of p62-KEAP1 to activate NRF2; however, it has also been shown to inhibit p62 phosphorylation and binding to KEAP1, preventing upregulation of NRF2 [34]. Another possible target is sestrin-2 (SESN2), a stress response protein that interacts with KEAP1 and RBX1 to promote the p62-dependent degradation of KEAP1 to upregulate NRF2 [40]. However, there are currently no established pharmacological activators of SESN2, and rapamycin has had limited success in clinical trials due to off target immunosuppressive effects [41]. It is also important to note that autophagy blockage leading to sustained activation, or “dark side”, of NRF2 has been shown to have negative consequences, particularly in the context of cancer, diabetes, and certain mutant protein-based cardiomyopathies [42–44]. Similarly, over-activation of autophagy may lead to autophagic cell death or “autosis” [45]. Since autophagy regulation and NRF2 activation are closely linked, both pathways should be carefully considered when designing novel autophagy or NRF2-based therapeutics.

NRF2 pathway inhibitors

The discovery of the “dark side” of NRF2 highlighted the need to develop inhibitors to be used when prolonged or uncontrolled activation of NRF2 causes tissue damage or cancer progression and chemoresistance. However, the discovery and development of specific, potent, and non-toxic NRF2 inhibitors has been elusive (Figure 1). The areas of opportunity for the development of specific inhibitors are (A) transcriptional downregulation of NRF2, (B) increased degradation of NRF2 mRNA or decreased translation, (C) enhancement of NRF2 degradation, through upregulation/activation of KEAP1-CUL3, β-TrCP-SCF, or HRD1; (D) blocking the dimerization of NRF2 with small MAF (sMAF) proteins; or (E) blocking the NRF2-sMAF DNA-binding domain. To date, very few putative inhibitors of NRF2 have been described. All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) treatment reduces the expression of ARE-regulated genes by activating retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα), which dimerizes with NRF2 and inhibits its transcription factor functions [46]. Brusatol, an inhibitor of global protein translation with strong effects on short-lived proteins like NRF2, can sensitize cancer cells to cisplatin in an NRF2-specific manner (Table 1) [47, 48]. Ochratoxin A has also been described as an NRF2 inhibitor with an unclear mechanism of action [49]. Overall, the development of anti-NRF2 therapeutics remains a fertile research area that will certainly constitute a new paradigm in the treatment of cancer and other chronic illnesses, like diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

Conclusions and future directions

While the canonical activation of NRF2 through electrophilic modification of KEAP1 has shown promise regarding pharmacological upregulation of NRF2 as a therapeutic strategy, the number of alternative pathways and targets that could be utilized to achieve upregulation of NRF2 continues to grow. One example is crosstalk with the autophagy lysosomal pathway via the p62-dependent regulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 interaction. As the studies presented earlier indicate, not only accumulation/sequestration, but also the post-translational modification of p62 can either enhance or inhibit its interaction with KEAP1, making p62 and the enzymes that modify it interesting therapeutic targets to alter NRF2 activity. Furthermore, other non-electrophilic modifiers of the KEAP1-NRF2 interaction, including peptides and small molecules designed to alter key KEAP-NRF2 binding motifs, are also being tested as alternative activators of the NRF2 pathway, and the NRF2 field has also benefited not only from an in-depth analysis of protein structure, but also the development of new research tools, like the fluorescent polarization (FP) assay, and high-throughput screening assays necessary to identify the activity of these small molecules [50, 51]. A number of KEAP1-independent E3 ubiquitin ligases of NRF2 have also been discovered, providing a new subset of possible pharmacological targets that can be used to regulate NRF2. Finally, recent evidence regarding the “dark side” of NRF2 has also argued for the need to develop inhibitors of NRF2. As the complexity of the interaction between NRF2 and other pathways continues to grow, so will the number of avenues to develop novel, safer, and more specific therapeutics for NRF2-targeted disease interventions.

Highlights.

The NRF2 pathway is recognized as a great therapeutic target

Only one NRF2-targeted therapeutic agent has been approved by the FDA

Understanding all the regulatory mechanisms that control NRF2 protein levels and activity will guide future development of NRF2-targeted therapeutics

Acknowledgments

The authors are funded by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: ES023758 (EC & DDZ), CA154377 (DDZ) and ES015010 (DDZ), and ES006694 (a center grant).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD, et al. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 1999;13(1):76–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.76. Epub 1999/01/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang DD, Lo SC, Cross JV, Templeton DJ, Hannink M. Keap1 is a redox-regulated substrate adaptor protein for a Cul3-dependent ubiquitin ligase complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(24):10941–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10941-10953.2004. Epub 2004/12/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, et al. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236(2):313–22. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. Epub 1997/07/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shu L, Cheung KL, Khor TO, Chen C, Kong AN. Phytochemicals: cancer chemoprevention and suppression of tumor onset and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(3):483–502. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9239-y. Epub 2010/08/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain A, Lamark T, Sjottem E, Larsen KB, Awuh JA, Overvatn A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(29):22576–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118976. Epub 2010/05/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau A, Wang XJ, Zhao F, Villeneuve NF, Wu T, Jiang T, et al. A noncanonical mechanism of Nrf2 activation by autophagy deficiency: direct interaction between Keap1 and p62. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(13):3275–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00248-10. Epub 2010/04/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, Taguchi K, Kobayashi A, Ichimura Y, et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(3):213–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb2021. Epub 2010/02/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan W, Tang Z, Chen D, Moughon D, Ding X, Chen S, et al. Keap1 facilitates p62-mediated ubiquitin aggregate clearance via autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6(5):614–21. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.12189. Epub 2010/05/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMahon M, Thomas N, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Hayes JD. Redox-regulated turnover of Nrf2 is determined by at least two separate protein domains, the redox-sensitive Neh2 degron and the redox-insensitive Neh6 degron. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31556–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403061200. Epub 2004/05/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rada P, Rojo AI, Chowdhry S, McMahon M, Hayes JD, Cuadrado A. SCF/{beta}-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(6):1121–33. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01204-10. Epub 2011/01/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chowdhry S, Zhang Y, McMahon M, Sutherland C, Cuadrado A, Hayes JD. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct beta-TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene. 2013;32(32):3765–81. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.388. Epub 2012/09/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu T, Zhao F, Gao B, Tan C, Yagishita N, Nakajima T, et al. Hrd1 suppresses Nrf2-mediated cellular protection during liver cirrhosis. Genes Dev. 2014;28(7):708–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.238246.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wattenberg LW. Inhibitors of chemical carcinogenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 1978;26:197–226. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benson AM, Batzinger RP, Ou SY, Bueding E, Cha YN, Talalay P. Elevation of hepatic glutathione S-transferase activities and protection against mutagenic metabolites of benzo(a)pyrene by dietary antioxidants. Cancer Res. 1978;38(12):4486–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L, Palliyaguru DL, Kensler TW. Frugal chemoprevention: targeting Nrf2 with foods rich in sulforaphane. Seminars in Oncology. 2016;43(1):146–53. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang DD. Bardoxolone brings Nrf2-based therapies to light. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(5):517–8. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5118. Epub 2012/12/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Giovannoni G, Selmaj K, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1098–107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114287. Epub 2012/09/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reisman SA, Goldsberry AR, Lee CY, O’Grady ML, Proksch JW, Ward KW, et al. Topical application of RTA 408 lotion activates Nrf2 in human skin and is well-tolerated by healthy human volunteers. BMC Dermatol. 2015;15:10. doi: 10.1186/s12895-015-0029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wondrak GT, Villeneuve NF, Lamore SD, Bause AS, Jiang T, Zhang DD. The cinnamon-derived dietary factor cinnamic aldehyde activates the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response in human epithelial colon cells. Molecules. 2010;15(5):3338–55. doi: 10.3390/molecules15053338. Epub 2010/07/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao S, Rojo de la Vega M, Quijada H, Wondrak GT, Wang T, Garcia JGN, et al. Bixin protects mice against ventilation-induced lung injury in an NRF2-dependent manner. Scientific Reports. 2015 doi: 10.1038/srep18760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson AJ, Kerns JK, Callahan JF, Moody CJ. Keap calm, and carry on covalently. J Med Chem. 2013;56(19):7463–76. doi: 10.1021/jm400224q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh T, McKercher SR, Lipton SA. Reprint of: Nrf2/ARE-mediated antioxidant actions of pro-electrophilic drugs. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;66:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.11.002. Epub 2013/11/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hancock R, Bertrand HC, Tsujita T, Naz S, El-Bakry A, Laoruchupong J, et al. Peptide inhibitors of the Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(2):444–51. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.486. Epub 2011/11/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •24.Wells G. Peptide and small molecule inhibitors of the Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43(4):674–9. doi: 10.1042/BST20150051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fosgerau K, Hoffmann T. Peptide therapeutics: current status and future directions. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(1):122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang ZY, Lu MC, Xu LL, Yang TT, Xi MY, Xu XL, et al. Discovery of potent Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction inhibitor based on molecular binding determinants analysis. J Med Chem. 2014;57(6):2736–45. doi: 10.1021/jm5000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •27.Marcotte D, Zeng W, Hus JC, McKenzie A, Hession C, Jin P, et al. Small molecules inhibit the interaction of Nrf2 and the Keap1 Kelch domain through a non-covalent mechanism. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21(14):4011–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.04.019. Epub 2013/05/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu L, Magesh S, Chen L, Wang L, Lewis TA, Chen Y, et al. Discovery of a small-molecule inhibitor and cellular probe of Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23(10):3039–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.013. Epub 2013/04/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun HP, Jiang ZY, Zhang MY, Lu MC, Yang TT, Pan Y, et al. Novel protein-protein interaction inhibitor of Nrf2-Keap1 discovered by structure-based virtual screening. Medchemcomm. 2014;5(1):93–8. doi: 10.1039/c3md00240c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaramillo MC, Zhang DD. The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev. 2013;27(20):2179–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.225680.113. Epub 2013/10/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •31.Rojo AI, Medina-Campos ON, Rada P, Zuniga-Toala A, Lopez-Gazcon A, Espada S, et al. Signaling pathways activated by the phytochemical nordihydroguaiaretic acid contribute to a Keap1-independent regulation of Nrf2 stability: Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(2):473–87. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orlicky S, Tang X, Neduva V, Elowe N, Brown ED, Sicheri F, et al. An allosteric inhibitor of substrate recognition by the SCF(Cdc4) ubiquitin ligase. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):733–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aghajan M, Jonai N, Flick K, Fu F, Luo M, Cai X, et al. Chemical genetics screen for enhancers of rapamycin identifies a specific inhibitor of an SCF family E3 ubiquitin ligase. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):738–42. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••34.Ichimura Y, Waguri S, Sou YS, Kageyama S, Hasegawa J, Ishimura R, et al. Phosphorylation of p62 activates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway during selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2013;51(5):618–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.003. Epub 2013/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •35.Pan JA, Sun Y, Jiang YP, Bott AJ, Jaber N, Dou Z, et al. TRIM21 Ubiquitylates SQSTM1/p62 and Suppresses Protein Sequestration to Regulate Redox Homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2016;62(1):149–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christian F, Krause E, Houslay MD, Baillie GS. PKA phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 regulates PB1 domain interaction partner binding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(11):2765–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsumoto G, Wada K, Okuno M, Kurosawa M, Nukina N. Serine 403 phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 regulates selective autophagic clearance of ubiquitinated proteins. Mol Cell. 2011;44(2):279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pilli M, Arko-Mensah J, Ponpuak M, Roberts E, Master S, Mandell MA, et al. TBK-1 promotes autophagy-mediated antimicrobial defense by controlling autophagosome maturation. Immunity. 2012;37(2):223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ro SH, Semple IA, Park H, Park H, Park HW, Kim M, et al. Sestrin2 promotes Unc-51-like kinase 1 mediated phosphorylation of p62/sequestosome-1. FEBS J. 2014;281(17):3816–27. doi: 10.1111/febs.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bae SH, Sung SH, Oh SY, Lim JM, Lee SK, Park YN, et al. Sestrins activate Nrf2 by promoting p62-dependent autophagic degradation of Keap1 and prevent oxidative liver damage. Cell Metab. 2013;17(1):73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sehgal SN. Rapamune (RAPA, rapamycin, sirolimus): mechanism of action immunosuppressive effect results from blockade of signal transduction and inhibition of cell cycle progression. Clin Biochem. 1998;31(5):335–40. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(98)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Zhou S, Jiang X, Wang YH, Li F, Wang YG, et al. The role of the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2015;16(1):35–45. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lau A, Villeneuve NF, Sun Z, Wong PK, Zhang DD. Dual roles of Nrf2 in cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58(5–6):262–70. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.09.003. Epub 2008/10/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brewer AC, Mustafi SB, Murray TV, Rajasekaran NS, Benjamin IJ. Reductive stress linked to small HSPs, G6PD, and Nrf2 pathways in heart disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(9):1114–27. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4914. Epub 2012/09/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Levine B. Autosis and autophagic cell death: the dark side of autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(3):367–76. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang XJ, Hayes JD, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. Identification of retinoic acid as an inhibitor of transcription factor Nrf2 through activation of retinoic acid receptor alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19589–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709483104. Epub 2007/12/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ren D, Villeneuve NF, Jiang T, Wu T, Lau A, Toppin HA, et al. Brusatol enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by inhibiting the Nrf2-mediated defense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(4):1433–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014275108. Epub 2011/01/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vartanian S, Ma TP, Lee J, Haverty PM, Kirkpatrick DS, Yu K, et al. Application of Mass Spectrometry Profiling to Establish Brusatol as an Inhibitor of Global Protein Synthesis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(4):1220–31. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.055509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Limonciel A, Jennings P. A review of the evidence that ochratoxin A is an Nrf2 inhibitor: implications for nephrotoxicity and renal carcinogenicity. Toxins (Basel) 2014;6(1):371–9. doi: 10.3390/toxins6010371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inoyama D, Chen Y, Huang X, Beamer LJ, Kong AN, Hu L. Optimization of fluorescently labeled Nrf2 peptide probes and the development of a fluorescence polarization assay for the discovery of inhibitors of Keap1-Nrf2 interaction. J Biomol Screen. 2012;17(4):435–47. doi: 10.1177/1087057111430124. Epub 2011/12/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendriks G, Atallah M, Morolli B, Calleja F, Ras-Verloop N, Huijskens I, et al. The ToxTracker assay: novel GFP reporter systems that provide mechanistic insight into the genotoxic properties of chemicals. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125(1):285–98. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]