Abstract

Aims

Depression and diabetes are highly comorbid, adversely affecting treatment adherence and resulting in poor outcomes. To improve treatment and outcomes for people dually-affected by diabetes and depression in India, we aimed to develop and test an integrated care model. In the formative phase of this INtegrated DEPrEssioN and Diabetes TreatmENT (INDEPENDENT) study, we sought stakeholder perspectives to inform culturally-sensitive adaptations of the intervention.

Methods

At our Delhi, Chennai, and Vishakhapatnam sites, we conducted focus groups for patients with diabetes and depression and interviewed healthcare workers, family members, and patients. These key informants were asked about experiences with diabetes and depression and for feedback on intervention materials. Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach.

Results

Three major themes emerged that have bearing on adaptation of the proposed intervention: importance of family assistance, concerns regarding patient/family understanding of diabetes, and feedback regarding the proposed intervention (e.g. adequate time needed for implementation; training program and intervention should address stigma).

Conclusions

Based on our findings, the following components would add value when incorporated into the intervention: 1) engaging families in the treatment process, 2) clear/simple written information, 3) clear non-jargon verbal explanations, and 4) coaching to help patients cope with stigma.

Keywords: Diabetes, Depression, Integrated Care Models, South Asia

Introduction

The global burden of diabetes is substantial, accounting for considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide.(Danaei et al.) Already, an estimated 387 million people across the world are living with diabetes(Guariguata et al., 2014) and diabetes accounts for close to 5 million deaths annually.(International Diabetes Federation, 2014) In India, 77.2 and 62.4 million people are affected by prediabetes and diabetes, respectively;(Anjana et al., 2011) and the results of a 10 year cohort study indicate that Indians have an extraordinarily high diabetes incidence and rapid conversion from prediabetes to diabetes, suggesting that the numbers will continue to increase.(Anjana et al., 2015) Furthermore, chronic diseases such as diabetes are a leading cause of death and disability in India.(Patel et al., 2011)

Studies from across India also show heightened prevalence of depression amongst people with diabetes.(Madhu et al., 2013; S Poongothai, Pradeepa, Ganesan, & Mohan, 2009; Siddiqui, Jha, Waghdhare, Agarwal, & Singh, 2014) Importantly, individuals with comorbid diabetes and depression are at increased risk for poor outcomes, often beyond the sum of expected outcomes of the individual conditions.(Mariska Bot, François Pouwer, Marij Zuidersma, Joost P. van Melle, & Peter de Jonge, 2012; Egede & Ellis, 2010; Koike, Unutzer, & Wells, 2002) The combination of depression and diabetes impairs diabetes treatment adherence,(W. J. Katon, J. E. Russo, et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2004) and is associated with poor glycemic control,(Lustman et al., 2000; Raheja et al., 2001) higher rates of microvascular and macrovascular complications,(Bajaj, Agarwal, Varma, & Singh, 2012; S. Poongothai et al., 2011) increased disability and decreased quality of life,(Egede & Ellis, 2010; Madhu et al., 2013) greater health service utilization,(Davydow et al., 2011; Egede, Zheng, & Simpson, 2002) and increased diabetes-specific mortality.(M. Bot, F. Pouwer, M. Zuidersma, J. P. van Melle, & P. de Jonge, 2012; W. Katon et al., 2008; W. J. Katon et al., 2005)

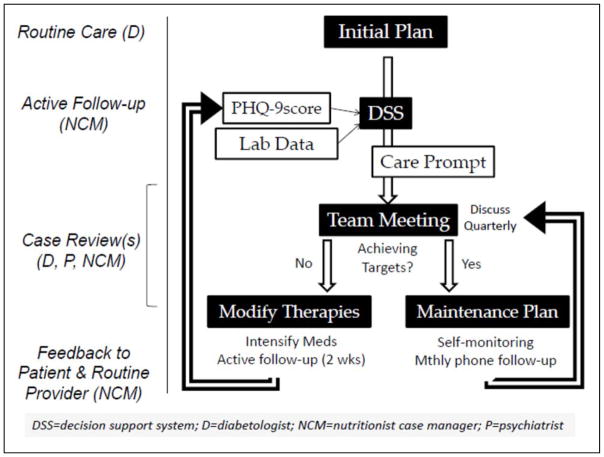

Evidence indicates that coordinated strategies simultaneously targeting diabetes and depression are effective in improving a variety of outcomes.(Bogner, Morales, Post, & Bruce, 2007; Hunkeler et al., 2006; W. J. Katon et al., 2004) In the United States, an integrated treatment model named TEAMcare combined patient-centered self-care goals with pharmacotherapy interventions to improve depression scores; control of glycemic, blood pressure, and lipids; and was associated with increased quality of life and greater satisfaction with care.(W. Katon et al., 2010; W. J. Katon, E. H. Lin, et al., 2010) Though the TEAMcare model offers promise for people with comorbid diabetes and depression in India, merely adapting an empirically supported intervention generated in the dominant culture is not sufficient and represents antiquated dissemination of evidence-based practice.(Wallerstein & Duran, 2010) Effective programs must be grounded in social, historical, cultural context and fostered within the relevant community.(Israel et al., 2008) Therefore, we designed an integrated care intervention based on both local programs (the Center for Cardiometabolic Risk Reduction in South Asia [CARRS] Trial (Shah et al., 2012) and the work of TEAMcare (See Figure 1). Furthermore, prior to implementing this culturally-appropriate care model (named INtegrated DEPrEssioN and Diabetes TreatmENT [INDEPENDENT]), we sought to gather information and perspectives from individuals involved in diabetes care in India to ensure the intervention aligns with the cultural and economic context in which it is situated.(Kalra, Balhara, & Mithal, 2013; Kalra, Sridhar, et al., 2013; Sridhar & Madhu, 2002) As its foundation, INDEPENDENT will include, 1) non-physician care coordinators that are trained in basic psychotherapeutic techniques (motivational interviewing, behavioral activation, problem solving techniques), 2) an electronic health record enhanced with guideline-based prompts for physicians, and 3) oversight by specialists to regularly audit and improve clinical decision-making. The goal of this qualitative study was to inform the culturally sensitive intervention modifications necessary for the INDEPENDENT model of diabetes and depression care to be effective in India.

Figure 1.

Methods

Subjects

The study took place at three sites in India: a private diabetes specialty center in Chennai, a private diabetes care clinic in Vishakhapatnam, and a public diabetes care center at a major medical center and training institution in Delhi. Key informants in the study met the following criteria: they were over the age of 18, native speakers of Tamil, Telugu, or Hindi, and were members of at least 1 of 3 key stakeholder groups 1) patients with depression and poorly controlled diabetes (i.e. elevated blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or glycated hemoglobin above guideline levels), 2) family members of patients, or 3) healthcare workers working in the diabetes care context (e.g. physicians and nutritionists who have a primary role in clinical management of diabetes in India).

To ensure data saturation (no new information emerges), we conducted 2 focus groups with diabetes patients at each of the 3 sites (total 6 focus groups with at least 5 participants in each group): 1 with men and 1 with women.(Halcomb, Gholizadeh, Digiacomo, Phillips, & Davidson, 2007) We also conducted 45 individual in-depth interviews to triangulate data from the focus groups, 15 at each of the 3 sites. At each site, 5 interviews were conducted with patients, 5 with family members, and 5 with healthcare workers. Based on previous experiences in supplementing focus group information with individual interviews, we expected that 15 key informant interviews at each site would be enough to reach data saturation.(Morse, 2000; Rao et al., 2008)

Materials and Procedures

Research assistant training

Research assistants from Vishakhapatnam and Chennai traveled to Delhi, where we trained them in Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item administration for optimal screening of potential key informants in the study. In addition, qualitative methods experts in Chennai trained the research assistants in interviewing techniques and focus group moderation.

Interview and focus group content

We conducted individual interviews and focus groups to elicit information on 1) the experience of living with diabetes and depression in India, and 2) the feasibility, content, and structure of the INDEPENDENT intervention, an integrated diabetes and depression care model. We specifically inquired about ways to refine the intervention for the Indian context, its cultural appropriateness and acceptability, potential barriers to implementation, and how the program could be taken up by clinics. Moderator guides contained semi-structured and open-ended questions to obtain feedback without biasing responses and probes to inquire about specific points of feedback on the intervention (See Appendix materials). Visual aids and intervention materials were used to describe the intervention.

For patients, questions focused on their personal experience e.g. What are the factors that have helped you to control diabetes? Do you think [the intervention] would be appropriate for you? Family members were asked similar questions pertaining to the family member with diabetes and depression e.g. What is your understanding of your family member’s diagnosis? If your family member were offered the opportunity to participate in [INDEPENDENT] would s/he choose to do so? Finally, healthcare workers were asked similar questions regarding their patients with diabetes and depression e.g. What has worked well and what has not worked so well in treating your patients with diabetes? Do you think [a component of the INDEPENDENT intervention] is appropriate for your patients? Instruments are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Recruitment

A research assistant approached potential key informants in the diabetes clinics, described the study, obtained informed consent, and scheduled focus groups or interviews at a time that was most convenient for the potential key informants. The research assistant then reviewed the medical record to abstract clinical information and solicited socio-demographic information from the key informant. We conducted the interviews and focus groups in local languages (Tamil in Chennai, Hindi in Delhi, and Telugu in Vishakapatnam). Each interview and focus group was audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. Participants were compensated with 200 Rupees to cover transportation and food costs. All recruitment, consent, and study procedures, including audiotaping sessions, were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at each of the sites, Emory University, and the University of Washington.

Data analysis

Once the focus group and interview data were transcribed, psychologists with extensive qualitative experience and training from Chennai independently coded the transcripts using QSR International’s NVivo qualitative analysis software.(Richards, 1999) The coders then jointly identified themes that emerged from the data using a grounded theory approach.(Corbin & Strauss, 2008) DR and the coding team met by phone to name the themes that emerged and resolve discrepancies between coders.

Emphasis was given to themes with the potential to guide the development of INDEPENDENT. We paid special attention to identifying barriers to implementation, points of modification for existing materials, and innovative ways to implement INDEPENDENT in an Indian context.

Results

In all, 82 people participated in the study: 45 key informants participated in individual interviews and 37 patients participated in focus groups. The mean age of participants was 44 (SD = 10.5), with a minimum age of 27 and a maximum of 67. Detailed demographic information on the participants is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information on Participants (Total n = 87).

| Variable | Mean (SD)/Frequency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Family Member | Healthcare Worker | Total | |

| Chennai Site | 21 (40.4) | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 31 (37.8) |

| Delhi Site | 16 (30.8) | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 26 (31.7) |

| Vishakhapatnam Site | 15 (28.8) | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 25 (30.5) |

| Age (All Sites) | 47 (9.2) | 44 (13.4) | 35 (6.1) | 44 (10.5) |

| Married (All Sites) | 51 (98.1) | 12 (80.0) | 12 (80) | 75 (91.5) |

| Female (All Sites) | 27 (51.9) | 10 (66.7) | 9 (60) | 46 (56.1) |

Key informant responses fell into 4 major themes: 1) importance of family assistance in diabetes care, 2) concerns over patient and families’ understanding of diabetes management, 3) stigma and labeling associated with diabetes and depression care, and 4) feedback on the intervention. We describe these themes and provide exemplary quotations from the respondents below.

Importance of family assistance

Patients, family members, and healthcare workers all discussed the importance of family assistance in supporting diabetes management. Some mentioned that food was an important aspect of family life, bringing family members together for festivals and regular meals. They noted that when a patient’s food was different from food being served to other family members, this caused much distress to the patient. Some mentioned that withholding certain foods led to patients binging at night. One family member in Chennai said,

‘He is crazy in taking snacks. I could not change him. Mostly I avoid preparing anything at home because he would eat it…But he likes eating outside rather than eating at home. I used to give him sundal (boiled pulses, seasoned with spices) but he likes to have that spicy not just simply boiled. So I am forced into making it spicy (laughs). So I put lot of effort to control him, but I could not do anything when he eats outside.’

Patients would oftentimes describe how family members were too strict with them. One patient from Vishakhapatnam said,

‘In social gatherings, my relatives and friends are focusing on me and trying to restrict and giving some advices like: ‘don’t do this’, ‘don’t eat this’, and so on. I don’t like this type sympathy and suggestion, mainly these leads me to be more depressive. Others’ feeling like it’s a deadly disease, they are asking some questions like ‘why you got this’? ‘Where did you get it’? Being a diabetic, I am totally restricted for my favorite foods and I lost my enjoyment, this is the main stressor for me.’

Patients recommended that family members remain open to negotiating which foods should be prepared at home. They described how family members needed suggestion from healthcare workers in order to work together with the patient and come to mutual agreements on treatment, nutrition, and exercise approaches, rather than strict, top-down approaches to nutrition.

Concern over patient and families’ understanding of diabetes

Several patients and family members did not immediately recognize the terms ‘diabetes’ or ‘depression’. Many used terms such as ‘sugar’ or ‘stress’ to describe the more Western terminologies of diabetes and depression, respectively. Other patients and family members defined depression as ‘anger’ or ‘aggression.’ Patients also described how much miseducation existed about diabetes. One key informant’s family in Delhi believed that diabetes was contagious by sharing utensils:

‘I am very sad. I always feel sad. A person (with diabetes) is always sad. Have problems, pain. Even people taunt that “she has got this disease”. Those having elder and younger sister-in-laws refrain; they also keep the utensils separate. Our family has many restrictions…They think because she (meaning me) has this, our family will also get this disease…But now they don’t do this because they heard from others that it does not spread like that. Initially they separated the utensils’

This key informant seemed to imply that this type of misinformation fueled her depressive symptoms.

Healthcare workers emphasized that much time was needed to bring patients and families to a point where they understood nutrition and exercise related to controlling diabetes. They suggested that similar time was needed to improve health literacy around depression. Some healthcare workers highlighted that they often needed to explain concepts without written materials, so that patients and families with limited literacy could understand the concepts.

Stigma and labeling

Many patients did not feel comfortable admitting that they had diabetes or ‘sugar’ in public. They didn’t like any public attention for their condition. A patient from Chennai said, ‘Near my home in my area they speak very bad about diabetes people. If there is a problem they talk like “what did you do to get diabetes and that is why you are suffering with diabetes”.’

In addition to stigmas associated with diabetes, one healthcare worker from Vishakhapatnam was concerned about layering stigmas associated with depression. He said:

‘This method will not work out for my clinic because we will be touching their family and personal aspects of their lives. Due to this reason patients will refuse to respond…In general patients seeks only medical assistance more than psychological support. They believe that psychological counselling is only meant for those who are having mental problems. Sometimes it will lead to degradation of the reputation of the clinic due to the negative attitude towards psychological counselling.’

This healthcare worker was quite concerned that patients wouldn’t want to discuss their problems or be labeled as having a mental health condition, and the stigma associated with a mental health condition would affect patient retention in his clinic. This comment was an outlier when compared to other healthcare workers feedback about handling mental health issues in a diabetes clinic. However, this comment was highlighted here to demonstrate that mental health issues carry their own stigmas in India, and the study team should remain attuned to compounded impacts that could occur as a result of adding a label of depression to people already feeling stigmatized as living with diabetes.

Feedback on the intervention

Nearly all of the healthcare workers, family members, and patients had positive things to say about the intervention materials that were presented. Patients and family members generally liked the idea of spending more time with their healthcare workers via counseling. A family member said, ‘Suggesting them to do activities that give them happiness is a good idea. This helps them to take their mind off from their illness.’ Other family members liked the idea of playing an active role in the patients’ treatment and exploring ways to motivate the patient.

Patients liked the opportunity to gain more knowledge of how to stay healthy. A patient from Chennai said,

‘[The care coordinator] can explain the benefits of doing exercise. Instead of just saying “go walking” they can explain that if you walk you will sweat, for some time you may feel tired but overall you will be energetic and can do the day’s work with enthusiasm. You will feel happy as though you have achieved, like if you walk for five kilometres and come back home, we feel we have done something great and achieved something.’

Overall, the patients, family members, and healthcare workers liked the explanation, activation, and coping mechanisms that the intervention materials contained.

The key informants did provide some explicit guidance on how to adapt the intervention for the Indian context. As noted above, adding a strong family component to the intervention was positively viewed. Key informants also cited unique barriers to exercise. A healthcare worker highlighted that some women might have additional challenges with safety, as walking in their communities was a common form of exercise, but women do not go out by themselves, particularly after dark. Patients and family members thought that discussing feasible exercises for their context with a care coordinator would be helpful.

Healthcare worker time constraints was another identified barrier to implementing the intervention in India. One healthcare worker in Vishakhapatnam said:

‘In my opinion this program will be useful in private hospitals where there are no major challenges, but in government hospitals it will be very difficult to establish because they need to appoint a new person for this program.’

This healthcare worker had concerns that staff would not have the time to provide additional counseling services, and clinics may need to hire new staff to take on the additional responsibilities. On the other hand, patient respondents did not voice a concern that the intervention may take more time. In fact, patient respondents appeared to enjoy the idea that a healthcare worker would be able to spend more time with them.

Conclusions

A well-adapted integrated approach to managing diabetes and depression has the potential to make a large impact in India. While integrated care models have shown great success in the United States,(W Katon et al., 1995; Tricco et al., 2012) there are many cultural factors to consider for an Indian audience. Through interviews and focus groups at three different sites around the country, our key informants provided much guidance on addressing topics at the intersection of depression and diabetes treatment in India.

Strengthening the family members’ role in patients’ diabetes and depression treatment was cited as a major facilitator to implementing the intervention in an Indian context. Specifically, key informants suggested family involvement in the care plan and joint discussions regarding what the patient can commit to achieving in terms of dietary choices, exercise, and medication adherence. Indeed, research indicates that family support improves the management of diabetes.(Rosland et al., 2008; Wen, Shepherd, & Parchman, 2004) Relatedly, a meta-analysis found that chronic disease interventions that include spouses can reduce patient depressive symptoms.(Martire, Lustig, Schulz, Miller, & Helgeson, 2004)

Health literacy and stigma are also salient characteristics of the Indian experience with diabetes and depression. Poor health literacy is associated with poor diabetes control and depressive symptoms. (Lincoln et al., 2006; Schillinger, Grumbach, Piette, & et al., 2002) Correspondingly, our key informants recommended that materials and messages given to patients and family members be simple and clear and time needs to be taken to ensure that patient and family understand the treatment options available. Using words that patients bring in themselves (e.g. sugar, tension, feeling low) and avoiding medical terminology may help establish rapport and promote patient participation and joint decision-making with healthcare workers. Simultaneously, the care coordinator can help patients strategize ways to avoid stigma in public (e.g. taking coffee with no sugar because that is the way that they prefer it, rather than because of a diabetes diagnosis).

Lastly, overcrowding and time constraints were identified as barriers for healthcare workers. Various strategies have been proposed for disseminating innovations in health including restructuring and quality management.(Powell et al., 2012) Indeed, investing in practice change or quality improvement interventions –even if it means higher upfront costs– can be very cost-effective and/or cost-saving on account of saving more physician time and savings related to better control and health outcomes. Incorporating operational research into the implementation process can help identify and quantify the value of approaches for maximizing efficiency.(Zachariah et al., 2009)

Limitations

Our study had important limitations. While there were a diversity of care settings (small private clinic, large private specialty hospital, and large public hospital clinic), there was a limited number of sites and sites were all located in major metropolitan cities. Our findings may therefore not be generalizable to rural settings or certain areas of the country. In addition, the sample size was small. Although sample sizes in qualitative research tend to be small in order to obtain rich data, this too limits the generalizability of our findings. Notably, the findings are context-specific and directly applicable to the next phase of implementation, as an effectiveness trial will be conducted at the same study sites from where the qualitative data was collected.

In conclusion, key informants expressed enthusiasm for intervening on depression in a diabetes context in India. Most importantly, they provided information towards developing an effective and culturally-appropriate intervention. Our findings indicate that the following components be incorporated into integrated care models for Indian urban settings: 1) formal engagement of family members in the treatment process, 2) clear and simple information and materials for patients and families, 3) use of patient-friendly language instead of medical jargon, 4) coaching for patients in coping with stigma, 5) cross-training of existing staff instead of hiring new staff, and 6) ongoing process evaluation. By combining these program elements with experiences from previous successful care models (e.g., TEAMcare, CARRS, etc.), the INDEPENDENT intervention has the potential to be an extremely effective option for depression and diabetes treatment in India.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge our participants, Professor K Madhu, Dr. NVVS Narayana, Majida Shaheen, and Mark Hutcheson for their invaluable contributions to the study. This study was funded by NIH grant R01 MH 100390 (PIs Ali, Mohan, Chwastiak).

Footnotes

Appendices

Interview guides (attached as supplemental file)

References

- Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Datta M, Sudha V, Unnikrishnan R, … Mohan V. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance) in urban and rural India: phase I results of the Indian Council of Medical Research-INdia DIABetes (ICMR-INDIAB) study. Diabetologia. 2011;54(12):3022–3027. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjana RM, Shanthi Rani CS, Deepa M, Pradeepa R, Sudha V, Divya Nair H, … Mohan V. Incidence of Diabetes and Prediabetes and Predictors of Progression Among Asian Indians: 10-Year Follow-up of the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) Diabetes Care. 2015 doi: 10.2337/dc14-2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj S, Agarwal SK, Varma A, Singh VK. Association of depression and its relation with complications in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(5):759–763. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.100670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Bruce ML. Diabetes, depression, and death: a randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment program for older adults based in primary care (PROSPECT) Diabetes Care. 2007;30(12):3005–3010. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bot M, Pouwer F, Zuidersma M, van Melle JP, de Jonge P. Association of Coexisting Diabetes and Depression With Mortality After Myocardial Infarction. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):503–509. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bot M, Pouwer F, Zuidersma M, van Melle JP, de Jonge P. Association of coexisting diabetes and depression with mortality after myocardial infarction. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):503–509. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, Singh GM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, … Ezzati M. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2·7 million participants. The Lancet. 378(9785):31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydow DS, Russo JE, Ludman E, Ciechanowski P, Lin EH, Von Korff M, … Katon WJ. The association of comorbid depression with intensive care unit admission in patients with diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(2):117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.12.020. S0033-3182(10)00043-5 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE, Ellis C. Diabetes and depression: global perspectives. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(3):302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):464–470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2014;103(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb E, Gholizadeh L, Digiacomo M, Phillips J, Davidson P. Literature review: considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007;16:1000–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K, Lin EH, … Unutzer J. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 2006;332(7536):259–263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas. (6) 2014 Retrieved from www.diabetesatlas.org.

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, III, Guzman JR. Community-based participatory research for health: from processes to outcomes. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles; p. 371388. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra S, Balhara YP, Mithal A. Cross-cultural variation in symptom perception of hypoglycemia. J Midlife Health. 2013;4(3):176–181. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.118998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra S, Sridhar GR, Balhara YP, Sahay RK, Bantwal G, Baruah MP, … Prasanna Kumar KM. National recommendations: Psychosocial management of diabetes in India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(3):376–395. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.111608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Fan MY, Unutzer J, Taylor J, Pincus H, Schoenbaum M. Depression and diabetes: a potentially lethal combination. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1571–1575. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0731-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Korff MV, Lin E, Walker E, Simon G, Bush T, … Russo J. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: Impact on depression in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, Young B, … McGregor M. Integrating depression and chronic disease care among patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease: the design of the TEAMcare study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31(4):312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.03.009. S1551-7144(10)00039-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, … McCulloch D. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Russo JE, Heckbert SR, Lin EH, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, … Von Korff M. The relationship between changes in depression symptoms and changes in health risk behaviors in patients with diabetes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(5):466–475. doi: 10.1002/gps.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski P, … Von Korff M. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2668–2672. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Simon G, Ludman E, Russo J, … Bush T. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike AK, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Improving the care for depression in patients with comorbid medical illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1738–1745. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Simon GE, Oliver M, … Young B. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Caruso C, Saitz R, Samet JH. Impact of health literacy on depressive symptoms and mental health-related: quality of life among adults with addiction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):818–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhu M, Abish A, Anu K, Jophin RI, Kiran AM, Vijayakumar K. Predictors of depression among patients with diabetes mellitus in Southern India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6(4):313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychol. 2004;23(6):599–611. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Chatterji S, Chisholm D, Ebrahim S, Gopalakrishna G, Mathers C, … Reddy KS. Chronic diseases and injuries in India. Lancet. 2011;377(9763):413–428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poongothai S, Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Ganesan A, Unnikrishnan R, Rema M, Mohan V. Association of depression with complications of type 2 diabetes--the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES- 102) J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:644–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poongothai S, Pradeepa R, Ganesan A, Mohan V. Prevalence of depression in a large urban South Indian population--the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-70) PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, … York JL. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123–157. doi: 10.1177/1077558711430690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raheja BS, Kapur A, Bhoraskar A, Sathe SR, Jorgensen LN, Moorthi SR, … Sahay BK. DiabCare Asia--India Study: diabetes care in India--current status. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:717–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Choi S, Victorson D, Bode R, Heinemann A, Peterman A, Cella D. Measuring Stigma Across Neurological Conditions: The Development of the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI) Quality of Life Research. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9475-1. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. Using NVivo in qualitative research. Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rosland AM, Kieffer E, Israel B, Cofield M, Palmisano G, Sinco B, … Heisler M. When is social support important? The association of family support and professional support with specific diabetes self-management behaviors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):1992–1999. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. ASsociation of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288(4):475–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Singh K, Ali MK, Mohan V, Kadir MM, Unnikrishnan AG, … Tandon N. Improving diabetes care: multi-component cardiovascular disease risk reduction strategies for people with diabetes in South Asia--the CARRS multi-center translation trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98(2):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui S, Jha S, Waghdhare S, Agarwal NB, Singh K. Prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes attending an outpatient clinic in India. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90(1068):552–556. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar G, Madhu K. Psychosocial and cultural issues in diabetes mellitus. Curr Sci. 2002;83:1556–1564. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Moher D, Turner L, Galipeau J, … Shojania K. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2252–2261. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American journal of public health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen LK, Shepherd MD, Parchman ML. Family support, diet, and exercise among older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(6):980–993. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah R, Harries AD, Ishikawa N, Rieder HL, Bissell K, Laserson K, … Reid T. Operational research in low-income countries: what, why, and how? Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(11):711–717. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(09)70229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]