Abstract

Recent scientific publications suggest that human longevity records stopped increasing. Our finding that mortality of centenarians does not decrease noticeably in the recent decades (despite a significant mortality decline in younger age groups) is consistent with this suggestion. However, there is no convincing evidence that we have reached the limit of human life span. The future of human longevity is not fixed and will depend on human efforts to extend life span.

Keywords: Longevity, Centenarians, Life expectancy, Life-history strategy, Limits to life span, Maximum life span, Maximum reported age at death, Mortality trajectories

How long can humans live? How long will we live in the future? These are very interesting and important questions to gerontologists, and also for demographers, actuaries and general public. Recent paper published by Jan Vijg and Éric Le Bourg claims that there is the inevitable limit to human life span around 115 years, and humans cannot reach the considerably longer life spans [1]. Our paper is a response to this publication.

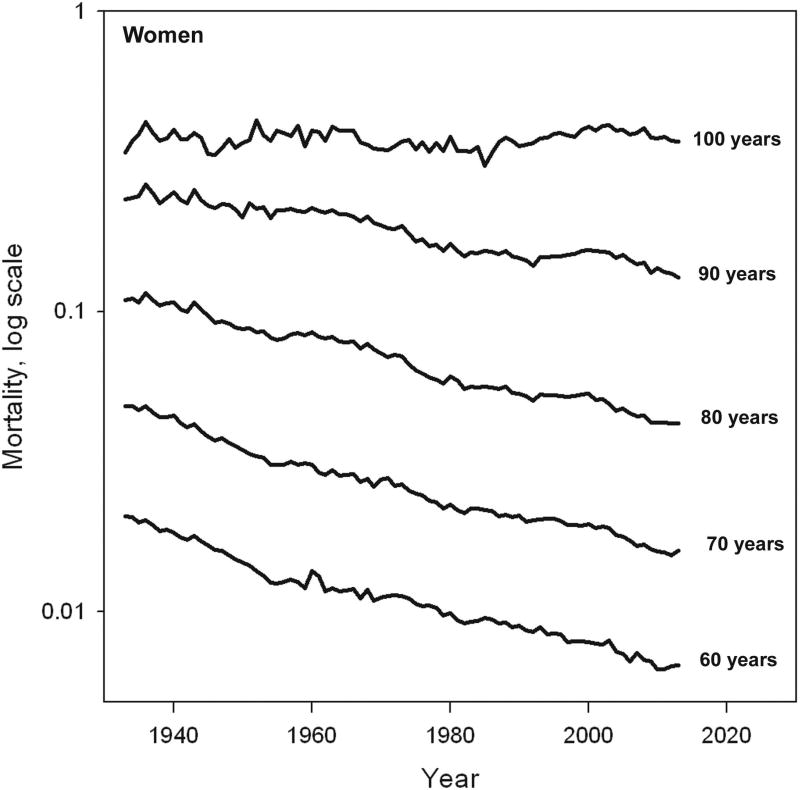

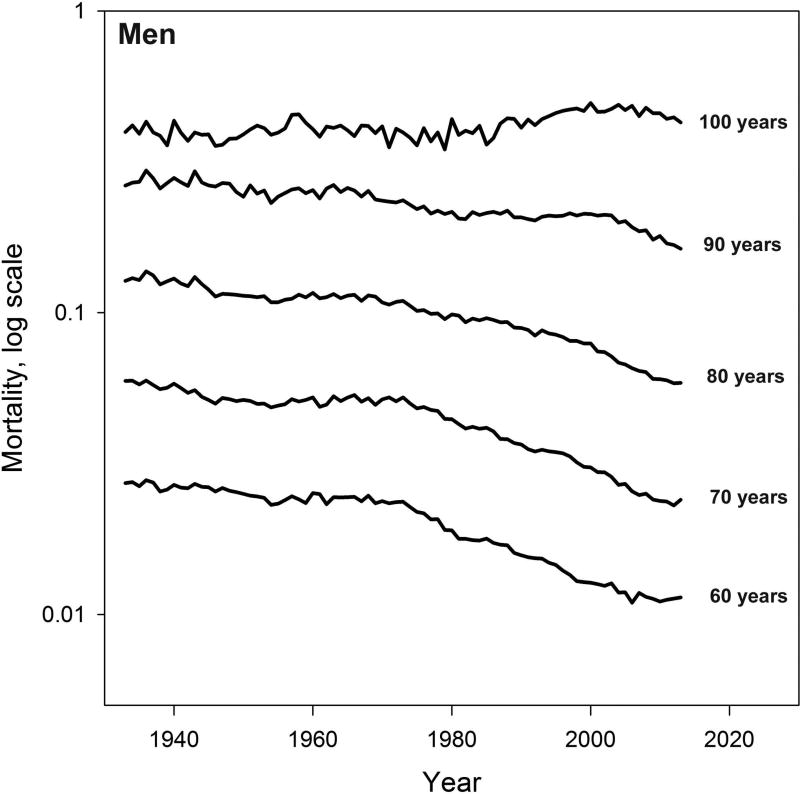

We will start by agreeing that recent demographic data support more conservative estimates for longevity records than previously thought. For example, mortality of centenarians does not decrease noticeably in recent decades, despite a significant decline in mortality of younger age groups (Figure 1). Thus, the projected estimates of old-age survival should be lower indeed than formerly believed.

Figure 1.

Time Trends of Old-Age Mortality for U.S. Men and Women. Age-specific death rates (available in the Human Mortality Database at www.mortality.org)

The second reason to be more conservative about human longevity records is related to the recent revision of mortality trajectories at older ages. Earlier studies assumed the so-called "old-age mortality deceleration", "mortality leveling-off" and "mortality plateaus", when death rates at extreme old ages do not grow as fast as at younger ages [2]. However studies of more recent and more reliable data suggest that mortality continues to grow exponentially with age (Gompertz law) even at extreme old ages [3, 4]. This means that the chances of exceptional survival are much smaller than earlier assumed.

Nevertheless, available data does not preclude a possibility that the maximum reported age at death (MRAD) continue to increase slowly over time. Jan Vijg and Éric Le Bourg cite recent article in Nature [5] in support of their claim that the maximum reported age at death has not increased for ca 25 years, and fluctuates around 115 years. Yet, several independent researchers challenged the conclusion of this Nature article, criticizing its methodological limitations. Their criticism is published online at academic website Publons [6] in the form of six post-publication peer-reviews.

Indeed, the maximum reported age at death in 2017 has exceeded 115 years thanks to the case of Italian supercentenarian Emma Martina Luigia Morano (29 November 1899 – 15 April 2017), who lived 117 years and 137 days [7]. This new case is consistent with possibility that the maximum reported age at death (MRAD) does continue slow increase over time.

Also according to the expert opinion of eminent gerontologist, Steven Austad, someone born before 2001 will reach the age of 150 years by the year 2150 [8]. Indeed, claiming the inevitable limit to human life span at about 115 years is equivalent to a claim of inevitable failure of all further efforts of gerontologists and other scientists in increasing human health-span (and subsequently longevity). The consensus letter published in Science by a group of 7 gerontologists states: "… there are currently no scientifically proven antiaging medicines, but legitimate and important scientific efforts are under way to develop them" [9]. There is no reason to believe that these efforts will inevitably fail [7].

Also note that the Nature study [5] cited by Jan Vijg and Éric Le Bourg, assumed that maximum reported age at death (MRAD) follows a Poisson distribution. This distribution does not have a fixed upper limit; therefore there is no inevitable fixed limit to human longevity, if we accept a hypothesis about Poisson distribution.

Jan Vijg and Éric Le Bourg argue that the close connection of species-specific longevity with life-history strategies explains why human life span is limited, and why age-related deterioration and death is an inevitable outcome. They cite theoretical work by Fisher, Haldane, Hamilton, Medawar, Williams, and Charlesworth who provided an evolutionary explanation of aging as a result of declining force of natural selection. However, this explanation can hardly be applied to extreme post-reproductive ages (100 years and older), when the force of natural selection is already negligible and hence has no room for its further decline. Life-history theory can not provide an accurate prediction of human longevity record - why is it 122 years (Jeanne Calment 1875–1997), but not 100 years only, for example. Also life-history theory can not explain why exactly the same exponential pattern of mortality growth with age (Gompertz law) is observed not only at reproductive ages, but also at very old post-reproductive ages (up to 106 years), long after the force of natural selection becomes insignificant (when there is no space for its additional decrease) [10].

To conclude, we agree with Jan Vijg and Éric Le Bourg that historical progress in human longevity records is very slow indeed. However we do not see really convincing evidence or a theory to claim that we have already approached the inevitable fixed limit to human life span. Temporary periods of lifespan stagnation have been already observed in the past in the 1960s and the 1970s [11], and then followed by further increase in lifespan. The future of human longevity is not fixed and depends on human efforts to increase it [7].

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (NG and LG), and the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (VK, Unique Project Identifier RFMEFI60715X0123).

References

- 1.Vijg J, Le Bourg E. Aging and the inevitable limit to human life span. Gerontology. doi: 10.1159/000477210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horiuchi S, Wilmoth JR. Deceleration in the age pattern of mortality at older ages. Demography. 1998;35:391–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS. Mortality measurement at advanced ages: A study of the social security administration death master file. North American Actuarial Journal. 2011;15:432–447. doi: 10.1080/10920277.2011.10597629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavrilova NS, Gavrilov LA. Biodemography of old-age mortality in humans and rodents. J Gerontol a-Biol. 2015;70:1–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong X, Milholland B, Vijg J. Evidence for a limit to human lifespan. Nature. 2016;538:257–259. doi: 10.1038/nature19793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Publons: Six post-publication peer-reviews of Nature article. "Evidence for a limit to human lifespan" [Internet] [retrieved 05.08.2017]. Available from: https://publons.com/publon/518732/

- 7.Harper S. Longevity, politics and science - moving from the outcomes to understanding the process. Journal of Population Aging. 2017;10:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming N. Scientists up stakes in bet on whether humans will live to 150. Nature. DOI: 101038/nature201620818. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Grey AD, Gavrilov L, Olshansky SJ, Coles LS, Cutler RG, Fossel M, Harman SM. Antiaging technology and pseudoscience [letter] Science. 2002;296:26. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5568.656a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS. New developments in biodemography of aging and longevity. Gerontology. 2015;61:364–371. doi: 10.1159/000369011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS, Nosov VN. Human life span stopped increasing: Why? Gerontology. 1983;29:176–180. doi: 10.1159/000213111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]