Abstract

Several cancer chemotherapies produce nausea and vomiting, which can limit dosing. Musk shrews are a preclinical model for chemotherapy-induced emesis and antiemetic effectiveness. Unlike rats and mice, shrews possess a vomiting reflex and demonstrate an emetic profile similar to humans, including acute and delayed phases. As for most animals, dosing of shrews is based on body weight, while translation of such doses to clinically equivalent exposure requires dose based on body surface area. In the current study we directly assessed body surface area in musk shrews to determine the Km conversion factor (female=9.97, male=9.10), allowing estimation of body surface area based on body weight. These parameters can be used to determine dosing strategies for shrew studies that model human drug exposures, particularly for investigating the emetic liability of cancer chemotherapeutic agents.

Keywords: Dosage, Body surface area, Emesis, Musk shrew, Refinement

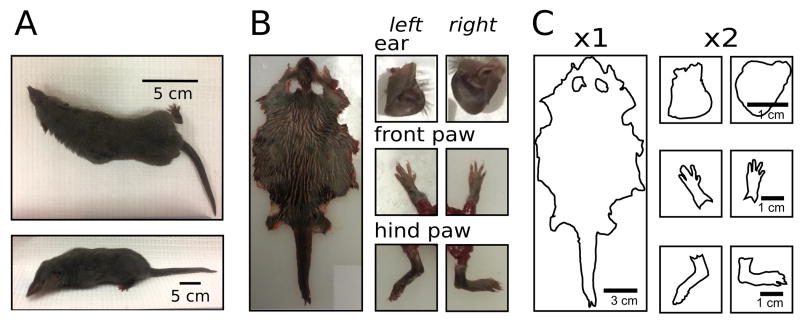

Despite the use of antiemetic drugs, notably the 5-HT3 (serotonin type 3) and NK1 (neurokinin type 1) receptor antagonists, classic cytotoxic and novel chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting remains a significant concern for patients1, 2. Although many studies of emesis use large animals, such as dogs and ferrets3, there has been a growing interest in the use of smaller animals, particularly musk shrews4, 5 (Fig.1A). Rodents (rats and mice) lack an emetic reflex and, therefore, are not suitable for emetic testing6.

Figure 1.

Analysis of body surface area. A) musk shrew. B) Skin was positioned flat for imaging; tissues were collected from a male (body weight=74.6, age=157 days). C) Skin surface area was computed in software; areas for the ears and paws were doubled to compute both sides.

To allow translation between body weight (BW) based doses in shrews and doses in humans on a body surface area (BSA) equivalent basis, we directly assessed BSA through image analysis of skin area to determine the Meeh's constant (Km) (a conversion factor between BSA and BW 7).

Sixty-one musk shrews (20 females, 52 to 213 days old; 41 males, 48 to 162 days old) were offspring from stock obtained from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (originating from Taiwan8), housed individually using a 12:12h light/dark cycle (lights on, 0700 h), and fed a mixture of 75% Purina Cat Chow Complete Formula and 25% Complete Gro-Fur mink food (Milk Specialty, New Holstein, WI), and free access to food and water. Experiments were approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the animal care and use program is approved by AAALAC.

Shrews were euthanized at the end of other, primary, studies using: (1) CO2 (rising); or (2) intracardiac injection of Beuthanasia-D (0.2 ml = 78 mg sodium pentobarbital, Henry Schein), under general anesthesia (urethane, 1 g/kg, ip) 5. Euthanization was confirmed by cervical dislocation. For dissection, a medial incision was made on the ventral plane from the tip of the lower jaw to the end of the tail. The skin was removed from the muscle, except for skin surrounding the paws, which was left in place. The ears were removed from the pelt and these tissues were laid flat, along with a metric ruler, for imaging with a digital camera (Fig.1B).

In ImageJ software, traces were made of the skin (Fig.1C). The total area was computed (converting the scale from pixels to cm) by subtracting the ear holes and adding the ears and paws, doubled to account for two surfaces (Fig.1C). We analyzed the data for male and females separately, and for each animal computed Km = BSA / (BW2/3) 9. The distribution of Km values were examined with histograms, and determined to be normally distributed based on the Shapiro-Wilks test, so the mean was calculated and used as an estimate of Km, including a 95% confidence interval (CI). The prediction error, defined as the observed BSA minus the calculated BSA was calculated for each animal and plotted against BW to see if the prediction error had a trend related to BW, but we did not see any trend for either sex, indicating that the data fitted the formula well. Also, the root mean squared prediction error (RMSE) was calculated for each data, along with its 95% CI 10. We used two-sided t-tests to compare males and females.

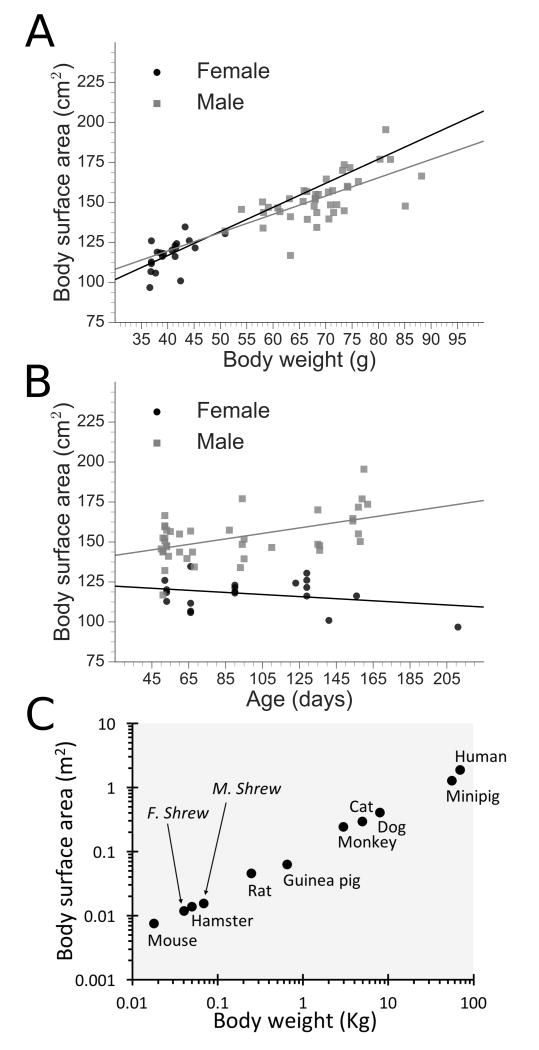

Females had a lower BW compared to males (mean=40.47, SD=3.62, median=40.00, range=36.60-50.90; compared to mean=68.91, SD=8.03, median=68.3 g, and range=50.90-88.20, p<0.0001); similarly, BSA was less in females (mean=117.5, SD=9.6, median=118.7, range=96.79-134.7; compared to mean=152.8, SD=14.3, median=150.6, and range=116.9-195.5 cm2, p<0.0001). See scatterplots for surface area by body weight (Fig.2A) and age (Fig.2B). Females had an average Km value of 9.97 (SD=0.68, median=10.12; 95% CI of 9.67 and 10.27; RMSE = 7.79 with 95% CI of 3.32 and 10.51) and males a value of 9.10 (SD=0.66, median=9.17; 95% CI of 8.81 and 9.39; RMSE = 11.21 with 95% CI of 8.05 and 13.66), respectively. The Km was significantly different between sexes (p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Summary data. A) Body surface area by body weight. B) Body surface area by age. C) Body surface area by body weight in female (f) and male (m) shrews compared to other mammals using logarithmic scales (monkey = cynomolgus, rhesus, and stumptail) 9.

Our data indicate that Km can be used to estimate BSA. Shrew BW relative to BSA is in close agreement with measures from other mammals (Fig.2C). Using shrew Km values, we estimated chemotherapeutic drug dosage from prior studies. Typical doses of the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin used in shrew studies of emesis were 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg BW4, 11-14, which convert to 100, 199, and 299 mg/m2 for females and 91, 182, and 273 for males (mg/kg value × Km). A cisplatin dosage of approximately >70 mg/m2 is highly emetogenic in humans15 but the equivalent dose in musk shrews (female, 7.0; male, 7.7 mg/kg) does not produce emesis. Ultrafilterable platinum clearance in our previous shrew pharmacokinetic study, normalized to BSA utilizing Km is 341 mL/min/m2, which is similar to that value reported in humans of 397 mL/min/m2 (assuming a 70 kg, 1.73 m2 human) 16, 17, suggesting there may be a susceptibility difference between humans and shrews.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Rosenberg, Nick Welko, Yolande Ramaroson, Audrey Lim, and Laura Farr for excellent technical assistance. We also thank the University of Pittsburgh, Division of Laboratory Animal Research, especially Megan Lambert and Dr. Joseph Newsome for excellent care of the shrew colony at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute.

Funding: Funding was supplied by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute NIH grant P30 CA047904 (Cancer Center Support Grant), with core support to the Animal Facility and the Cancer Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics Facility, and grant U18EB021772 from the Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions (SPARC) program at NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hesketh PJ. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2482–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waqar SN, Mann J, Baggstrom MQ, et al. Delayed nausea and vomiting from carboplatin doublet chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:700–4. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2016.1154603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horn CC. The medical implications of gastrointestinal vagal afferent pathways in nausea and vomiting. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:2703–12. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan SW, Lu Z, Lin G, Yew DT, Yeung CK, Rudd JA. The differential antiemetic properties of GLP-1 receptor antagonist, exendin (9-39) in Suncus murinus (house musk shrew) Neuropharmacology. 2014;83:71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horn CC, Zirpel L, Sciullo MG, Rosenberg DM. Impact of electrical stimulation of the stomach on gastric distension-induced emesis in the musk shrew. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1217–32. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horn CC, Kimball BA, Wang H, et al. Why can't rodents vomit? A comparative behavioral, anatomical, and physiological study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freireich EJ, Gehan EA, Rall DP, Schmidt LH, Skipper HE. Quantitative comparison of toxicity of anticancer agents in mouse, rat, hamster, dog, monkey, and man. Cancer chemotherapy reports. 1966;50:219–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C. Introduction: A new experimental animal, Suncus murinus. In: Saito H, Wang C, Chen C, editors. Proceeding of ROC-Japan Symposium on Suncus murinus. Chia Nan Junior College of Pharmacy Press; Chia Nan, Taiwan: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA. Guidance for Industry: Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers. Rockville, MD: FDA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheiner LB, Beal SL. Some suggestions for measuring predictive performance. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1981;9:503–12. doi: 10.1007/BF01060893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang D, Meyers K, Henry S, De la Torre F, Horn CC. Computerized detection and analysis of cancer chemotherapy-induced emesis in a small animal model, musk shrew. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;197:249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horn CC, Still L, Fitzgerald C, Friedman MI. Food restriction, refeeding, and gastric fill fail to affect emesis in musk shrews. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G25–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00366.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuki N, Ueno S, Kaji T, Ishihara A, Wang CH, Saito H. Emesis induced by cancer chemotherapeutic agents in the Suncus murinus: a new experimental model. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1988;48:303–6. doi: 10.1254/jjp.48.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Jonghe BC, Horn CC. Chemotherapy agent cisplatin induces 48-h Fos expression in the brain of a vomiting species, the house musk shrew (Suncus murinus) Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R902–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90952.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan K, Warr DG, Hinke A, Sun L, Hesketh PJ. Defining the efficacy of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists in controlling chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in different emetogenic settings-a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1941–54. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2990-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiseman JL, Beumer JH, Rigatti LH, et al. Plasma pharmacokinetics and tissue and brain distribution of cisplatin in musk shrews. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;75:143–52. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2623-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urien S, Lokiec F. Population pharmacokinetics of total and unbound plasma cisplatin in adult patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:756–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]