Abstract

Certain probiotic species of lactic acid bacteria, especially Lactobacillus plantarum, regulate bacteriocin synthesis through quorum sensing (QS) systems. In this study, we aimed to investigate the luxS-mediated molecular mechanisms of QS during bacteriocin synthesis by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391. In the absence of luxS, the ‘spot-on-the-lawn’ method showed that the bacteriocin production by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 significantly decreased upon co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 (P < 0.01) but did not change significantly when mono-cultivated. Furthermore, liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry analysis showed that, as a response to luxS deletion, L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 altered the expression level of proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, fatty acid synthesis and metabolism, and the two-component regulatory system. In particular, the sensor histidine kinase AgrC (from the two-component system, LytTR family) was expressed differently between the luxS mutant and the wild-type strain during co-cultivation, whereas no significant differences in proteins related to bacteriocin biosynthesis were found upon mono-cultivation. In summary, we found that the production of bacteriocin was regulated by carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, fatty acid synthesis and metabolism, and the two-component regulatory system. Furthermore, our results demonstrate the role of luxS-mediated molecular mechanisms in bacteriocin production.

Introduction

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) produce antimicrobial metabolites and have been traditionally used as starter cultures for different fermented foods, medicine, and feed. The production of metabolites such as organic acids, ethanol, hydrogen peroxide, and diacetyl is associated with the preservative and inhibitory effects of a few bacterial strains1. The preservative effect of many LAB is likely due in part to their bacteriocin production, which provides an advantage to producers in competing with other bacteria sharing the same ecological niche2,3. For example, Lactobacillus plantarum constitutes a flexible and versatile facultative heterofermentative LAB found in food environments such as vegetables, meat, aquatics, dairy products, and grape must, as well as in the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and animals. Accordingly, to enable effective adaptation to changeable environmental conditions (e.g. co-cultivation with other bacteria, pH, and heat), L. plantarum requires quorum sensing (QS) systems to detect specific environmental signals4.

QS, in which gene transcription is regulated in response to a change in cell density, is mediated by direct cell-cell contact or by the synthesis, release, and detection of small signalling molecules5. The QS system comprises two components: the first consists of signalling molecules, which are referred to as autoinducers (AIs, including AI-1 and AI-2) or AI peptides (AIP); the second is the two-component regulatory system, which comprises the membrane-located histidine protein kinase that monitors one or more environmental factors, as well as the cytoplasmic response regulator that modulates the expression of specific genes. Through adopting co-culture conditions or by constructing a two-component or AI-2/luxS mutant strain, previous studies6,7 have demonstrated that bacteriocin production is regulated via the QS pathway. Specifically, the induction of bacteriocin production by co-culture is widespread among bacteriocin-producing L. plantarum strains8. In particular, AI-2, which constitutes a by-product of the activated methyl cycle by which S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) is recycled, might play a role in the synthesis of bacteriocin9. AI-2 is formed by the catalysis of S-ribosylhomocysteine (SRH) via the LuxS enzyme, where SRH is the product of detoxification of S-adenosylhomocysteine, a demethylated product of SAM, by the enzyme Pfs9. The involvement of LuxS in the production of AI-2 is often found in Firmicutes and more particularly in Lactobacillus 10. Although the role of LuxS in the AI-2 biosynthetic pathway is consistent across different bacterial species, as summarized by Pereira et al.9, the AI-2 signal export and reception/transduction pathways in Lactobacillus spp., or closely related genera, have not yet been elucidated11. In addition to genetic tools, proteomic studies on QS, particularly under stressful conditions, such as co-cultivation with certain bacteria12, and presence of a luxS mutation13, might provide a more comprehensive view of the bacteriocin production mechanisms.

L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 was isolated from ‘jiaoke’, a traditional, naturally fermented cream from Inner Mongolia in China. The bacteriocin produced by this strain, plantaricin MG, offers the advantages of a broad inhibitory spectrum, wide pH tolerance, and heat stability, but is produced at lower levels than nisin produced by the commercial strain L. lactis AL214,15. Furthermore, we found that the bacteriocin production by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 was markedly increased (P < 0.01) when co-cultivated with L. helveticus KLDS1.920716, a strain that does not produce bacteriocins. In addition, L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 possesses an AI-2-mediated two-component system16, whereas L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 does not. Given that AI-2 might play a role in the synthesis of bacteriocins, we deduced that the luxS gene might be associated with the biosynthesis step of bacteriocin production. Moreover, bacteriocin production by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 was markedly influenced (P < 0.05) by the co-cultivation conditions15. However, whether the effect of luxS on bacteriocin production is affected by the selective culture conditions remains to be determined.

Therefore, in our previous research, we constructed a luxS mutant strain of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 by homologous recombination (manuscript submitted, under review) to illustrate the effect of luxS on bacteriocin production in mono-cultivation and co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207. In the present study, we further aimed to investigate luxS-mediated molecular mechanisms in the bacteriocin synthesis by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 upon co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 and during mono-cultivation, using a label-free quantitative shotgun proteomics strategy.

Results

Comparison of live cell number and bacteriocin production between luxS mutant and the wild-type strain in mono- and co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207

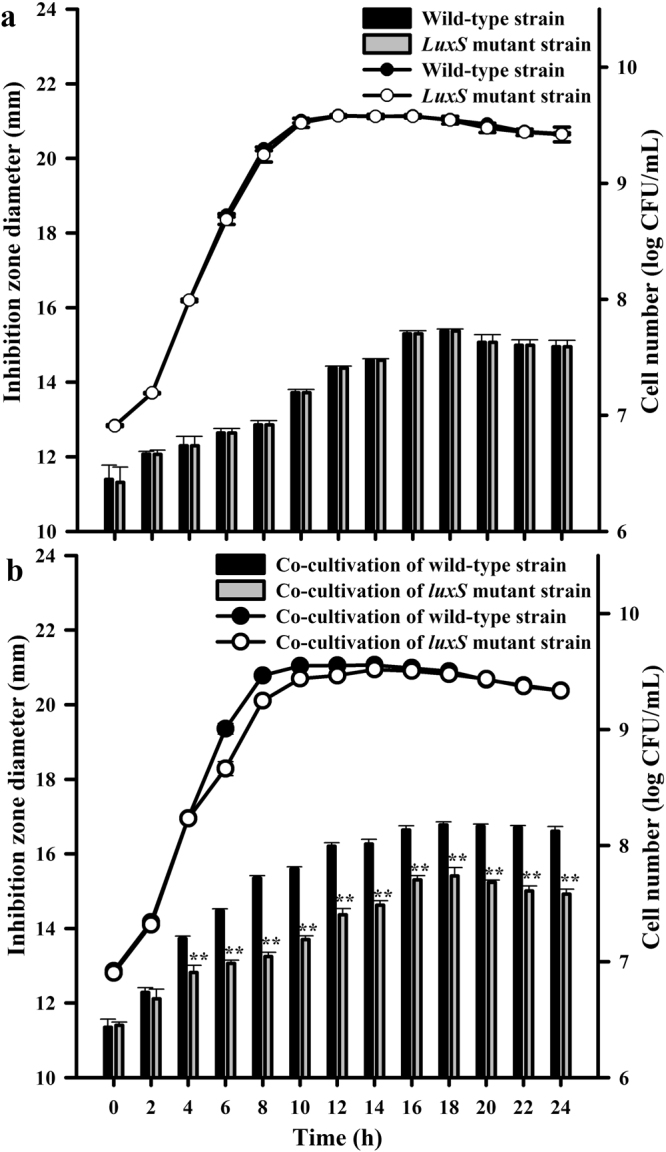

The live cell numbers and inhibition zone diameters of the luxS mutant and wild-type strains in mono-cultivation (a) and in co-cultivation (b) with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 are shown in Fig. 1. The live cell number of the luxS mutant strain compared to that of the wild-type strain in mono-cultivation was not markedly changed (P > 0.05) but was significantly lower than that of the wild-type strain upon co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 during a growth period of 6–12 h (P < 0.01). The antibacterial activity of the luxS mutant strain was significantly decreased (P < 0.01) compared with that of the wild-type strain in co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 during growth for 4–24 h; however, the antibacterial activity showed little change during mono-cultivation.

Figure 1.

Cell number ( ,

,  ) and inhibitory activity (

) and inhibitory activity ( ,

,  ) of wild-type and luxS mutant strains in mono-cultivation (a) and co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 (b). Cell number and inhibition zone diameter (inhibitory activity) are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3). **Statistically significant difference between wild-type strain and luxS mutant strain (P < 0.01).

) of wild-type and luxS mutant strains in mono-cultivation (a) and co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 (b). Cell number and inhibition zone diameter (inhibitory activity) are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3). **Statistically significant difference between wild-type strain and luxS mutant strain (P < 0.01).

Differentially expressed proteins between the wild-type and luxS mutant strains in mono- and co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207

In accordance with the selection criteria of ratio >±2 and P value < 0.05, we identified 108 differentially expressed proteins (Table 1) from the mono-cultivation group and 49 differentially expressed proteins (Table 2) from the co-cultivation group. The 108 proteins from the mono-cultivation group included 39 significantly differently expressed proteins (26 and 13 proteins with significant down- or upregulation, respectively) and 69 proteins for which the expression was below the detection limit of mass spectrometry (MS). The 49 proteins from the co-cultivation group included 13 significantly differentially expressed proteins (2 and 11 proteins with significant down- or upregulation, respectively) and 36 proteins below the MS detection limit.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed proteins between the luxS mutant and the wild-type strain in mono-cultivation.

| NO. | Protein ID | Map Name | Sequence description | Quantitative change and significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/Ba | P value | ||||

| 1 | A0A0R2GFJ4 | PTS-Bgl-EIIA, bglF, bglP | PTS system trehalose-specific IIB component | 0.477850866 | 4.015 |

| 2 | A0A0R2G9N6 | DLAT, aceF, pdhC | Dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex | 0.334091875 | 6.857 |

| 3 | A0A166KZ80 | E2.4.1.8, mapA | Maltose phosphorylase | 0.124908833 | 0.000 |

| 4 | A0A0G9FF05 | msmX, msmK, malK, sugC, ggtA, msiK | Maltose maltodextrin transport ATP-binding | 0.032826035 | 0.000 |

| 5 | A0A166HX81 | Promiscuous sugar phosphatase haloaciddehalogenase-like phosphatase family | 0.458219978 | 0.001 | |

| 6 | A0A162HJ67 | pgmB | Beta-phosphoglucomutase | 0.224240296 | 0.001 |

| 7 | A0A0R1UMU3 | PDHA, pdhA | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit | 0.30363946 | 0.002 |

| 8 | A0A0G9FDH3 | DLD, lpd, pdhD | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex | 0.335633652 | 0.002 |

| 9 | A0A0R1UYF1 | PTS-Cel-EIIB, celA, chbB | PTS system cellobiose-specific IIB component | 0.313399828 | 0.002 |

| 10 | A0A0G9FEW8 | cycB, ganO | Sugar ABC transporter substrate-binding | 0.095777705 | 0.002 |

| 11 | A0A166LCG7 | Oxidoreductase aldo keto reductase family | 0.22210812 | 0.002 | |

| 12 | A0A166J2F1 | rbsK, RBKS | Ribokinase | 0.399403783 | 0.002 |

| 13 | A0A0P7HSH4 | hprK, ptsK | HPr kinase phosphorylase | 0.389065012 | 0.004 |

| 14 | A0A166K0Z7 | PDHB, pdhB | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component beta subunit | 0.327629226 | 0.004 |

| 15 | A0A0G9F747 | PTS-Man-EIIC, manY | PTS system mannose-specific IIC component | 0.443786982 | 0.004 |

| 16 | D7V9C7 | malY, malT | Sugar transporter | 0.145274287 | 0.007 |

| 17 | A0A151G230 | galM, GALM | Galactose mutarotase | 0.328294689 | 0.018 |

| 18 | A0A0P7HQL7 | NADH oxidase | 0.374619026 | 0.019 | |

| 19 | Q88WV2 | nrdR | Transcriptional regulator | 0.391799787 | 0.025 |

| 20 | P59407 | E4.1.3.3, nanA, NPL | N-acetylneuraminate lyase | 0.169766187 | 0.027 |

| 21 | A0A0G9FD31 | E2.4.1.8, mapA | Maltose phosphorylase | 0.127697815 | 0.030 |

| 22 | A0A0R2GC45 | alsD, budA, aldC | Alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase | 0.42085536 | 0.046 |

| 23 | A0A0G9F7H9 | Malolactic regulator | 0.423614866 | 0.046 | |

| 24 | D7V885 | ackA | Acetate kinase | 0.485433255 | 0.046 |

| 25 | D7V7S0 | thiM | Hydroxyethylthiazole kinase | 0.415559565 | 0.046 |

| 26 | A0A0G9GMV5 | GSR, gor | Glutathione reductase | 0.399381865 | 0.050 |

| 27 | D7V8Y5 | glk | Glucokinase | 11.67055987 | 0.000 |

| 28 | A0A166LM67 | E3.2.1.17 | Cell wall hydrolase | 2.178588789 | 0.001 |

| 29 | A0A166LGI2 | Glycoside hydrolase family 25 | 2.239080765 | 0.005 | |

| 30 | A0A151G2W4 | PTS-Nag-EIIC, nagE | PTS N-acetylglucosamine transporter subunit IIABC | 2.406888508 | 0.007 |

| 31 | A0A165US72 | E1.17.4.1 A, nrdA, nrdE | Ribonucleotide reductase of class Ib alpha subunit | 2.079065281 | 0.007 |

| 32 | A0A0G9GSZ0 | pgmB | Beta-phosphoglucomutase | 2.059377081 | 0.008 |

| 33 | A0A0N8I4I6 | Alcohol dehydrogenase | 3.131477189 | 0.012 | |

| 34 | Q88YZ4 | fabH | 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier-) synthase KASIII | 2.254202031 | 0.014 |

| 35 | A0A0G9FGA4 | Diadenosine tetraphosphatase and related serine threonine phosphatase | 2.401060831 | 0.016 | |

| 36 | A0A0P7HQH4 | Hypothetical protein | 3.610968428 | 0.018 | |

| 37 | A0A166H1G4 | K06904 | Phage capsid protein | 2.019174041 | 0.019 |

| 38 | D7VEU7 | K06889 | Hydrolase of the alpha beta superfamily | 2.462973125 | 0.020 |

| 39 | A0A0G9FH00 | Multispecies: hypothetical protein | 2.438489371 | 0.023 | |

| 40 | Q88T16 | E5.2.1.8 | Foldase precursor | ||

| 41 | Q88V03 | ruvB | Holliday junction DNA helicase | ||

| 42 | Q88V79 | mraY | Phospho-N-acetylmuramoyl-pentapeptide-transferase | ||

| 43 | Q88WJ2 | trmD | tRNA -methyltransferase | ||

| 44 | Q88WP5 | miaA, TRIT1 | tRNA dimethylallyltransferase | ||

| 45 | Q88XV1 | ecfA2 | ATPase component of ral energizing module of ECF transporter | ||

| 46 | Q88ZU5 | serC, PSAT1 | Phosphoserine aminotransferase | ||

| 47 | A0A059UCU6 | ganP | Maltose maltodextrin ABC transporter permease | ||

| 48 | A0A0G9F7Q4 | ABC.CD.A | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | ||

| 49 | A0A0G9F9N1 | rluD | RNA pseudouridine synthase | ||

| 50 | A0A0G9F9S7 | HAD family hydrolase | |||

| 51 | A0A0G9F9Y3 | Nudix-related transcriptional regulator | |||

| 52 | A0A0G9FAX4 | HAD family hydrolase | |||

| 53 | A0A0G9FBB9 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| 54 | A0A0G9FCP4 | Cell surface protein | |||

| 55 | A0A0G9FHS8 | Negative regulator of proteolysis | |||

| 56 | A0A0G9GIU3 | GSP13 | General stress protein | ||

| 57 | A0A0G9GQE3 | K06910 | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein | ||

| 58 | A0A0G9GQZ7 | Multispecies: hypothetical protein | |||

| 59 | A0A0L7Y046 | Transcription regulator (contains diacylglycerol kinase catalytic domain) | |||

| 60 | A0A0L7Y0D5 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| 61 | A0A0L7Y739 | Acyl- hydrolase | |||

| 62 | A0A0M0CEA0 | Regulator | |||

| 63 | A0A0M0CFS2 | Damage-inducible J | |||

| 64 | A0A0M0CG41 | E1.2.3.3, poxL | Pyruvate oxidase | ||

| 65 | A0A0M0CHM2 | treC | Trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase | ||

| 66 | A0A0M4CWX9 | Methionine–tRNA ligase | |||

| 67 | A0A0P7GJ96 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| 68 | A0A0P7HFF8 | DUF2273 domain-containing | |||

| 69 | A0A0P7HGY1 | ABC-2.P | ABC transporter permease | ||

| 70 | A0A0P7HHH5 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| 71 | A0A0P7HNH7 | Hypothetical cytosolic | |||

| 72 | A0A0P7HSW4 | ISSag6 transposase | |||

| 73 | A0A0P7IQD5 | Stress response regulator Gls24 | |||

| 74 | A0A0R1UP09 | iunH | Inosine-uridine preferring nucleoside hydrolase | ||

| 75 | A0A0R1USD0 | coaE | Dephospho- kinase | ||

| 76 | A0A0R1V037 | ORF00007-like (plasmid) | |||

| 77 | A0A0R1V1M0 | ribT | Riboflavin biosynthesis acetyltransferase family | ||

| 78 | A0A0R1V308 | Extracellular | |||

| 79 | A0A0R1V7I4 | Conjugal transfer | |||

| 80 | A0A0R2G5K4 | Lipoprotein | |||

| 81 | A0A0R2G8W3 | rlmA1 | Ribosomal RNA large subunit methyltransferase A | ||

| 82 | A0A0R2GD86 | E1.2.3.3, poxL | Pyruvate oxidase | ||

| 83 | A0A0R2GG38 | TPR repeat-containing | |||

| 84 | A0A0R2GH14 | Isochorismatase | |||

| 85 | A0A151G1C3 | Transcription regulator | |||

| 86 | A0A151G5I5 | Membrane (plasmid) | |||

| 87 | A0A162EN38 | virD4, lvhD4 | Conjugal transfer | ||

| 88 | A0A162GM58 | Multispecies: hypothetical protein | |||

| 89 | A0A162GZ91 | Conjugal transfer | |||

| 90 | A0A165DXD9 | phoR | Phosphate regulon sensor | ||

| 91 | A0A165EXC6 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| 92 | A0A165VBP4 | fabK | 2-nitropropane dioxygenase | ||

| 93 | A0A165X1Y3 | D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | |||

| 94 | A0A165ZPF4 | Cell surface protein | |||

| 95 | A0A166FZ63 | Plasmid replication initiation | |||

| 96 | A0A166P0P2 | Transposase | |||

| 97 | C3U0I3 | rRNA adenine N-6-methyltransferase | |||

| 98 | D7VDC6 | Lipoprotein | |||

| 99 | D7VEF6 | DNA double-strand break repair Rad50 ATPase | |||

| 100 | T5JG80 | K09963 | Outer surface protein | ||

| 101 | T5JJD7 | ABC.PE.S | Peptide ABC transporter substrate-binding | ||

| 102 | T5JNS0 | Rrf2 family transcriptional regulator | |||

| 103 | T5JPM7 | Membrane anchor connecting 2 with cell-division Z-ring | |||

| 104 | T5JTG7 | Biphenyl-2 3-diol 1 2-dioxygenase III-related | |||

| 105 | T5JY38 | ispE | 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritolkinase | ||

| 106 | T5K0G6 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| 107 | U2XGM5 | priA | Primosomal protein N | ||

| 108 | U2XSX3 | Putative ABC transporter, permease protein | |||

aA: LuxS mutant strain; B: Wild-type strain.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed proteins between the luxS mutant and the wild-type strain in co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207.

| NO. | Sequence name | Map Name | Sequence description | Quantitative change and significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C/Db | P value | ||||

| 1 | P77887 | pyrDI | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase catalytic subunit | 2.760886385 | 0.031 |

| 2 | A0A0G9FAP4 | Transcriptional regulator family | 2.945902345 | 0.003 | |

| 3 | A0A0G9FCW2 | GNAT family acetyltransferase | 2.070695848 | 0.030 | |

| 4 | A0A0L7XZQ3 | Gamma-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelate peptidase | 2.747063118 | 0.036 | |

| 5 | A0A0R1UXL5 | E4.1.1.15 | Glutamate decarboxylase | 2.146220812 | 0.039 |

| 6 | A0A0R1VEW0 | Transcriptional regulator | 0.45197274 | 0.028 | |

| 7 | A0A0R2GIZ8 | Uncharacterized protein | 2.038790183 | 0.003 | |

| 8 | D7VFU5 | htpX | Heat shock | 0.427200477 | 0.001 |

| 9 | M4KFL2 | Acyltransferase | 2.708140733 | 0.004 | |

| 10 | U2W2U5 | Multispecies: hypothetical protein | 2.282826367 | 0.016 | |

| 11 | U2W7H2 | D-lactate dehydrogenase | 2.019712705 | 0.045 | |

| 12 | U2WKG8 | prsA | Peptidylprolyl isomerase | 2.070595076 | 0.042 |

| 13 | U2WLF8 | Nucleoside 2-deoxyribosyltransferase | 2.311437674 | 0.013 | |

| 14 | C6VLJ0 | accD | Acetyl- carboxyl transferase | ||

| 15 | Q88VX7 | clpB | ATP-dependent chaperone | ||

| 16 | Q88WT1 | agrC, blpH, fsrC | UPF0348 lp_1534 | ||

| 17 | A0A0G9F856 | Histidine kinase | |||

| 18 | A0A0G9F9S7 | HAD family hydrolase | |||

| 19 | A0A0G9FBJ9 | Oxidoreductase aldo keto reductase family | |||

| 20 | A0A0G9FCA3 | Dimeric dUTPase | |||

| 21 | A0A0G9FE10 | recX | Recombinase | ||

| 22 | A0A0G9FGT8 | fabG | 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier) reductase | ||

| 23 | A0A0G9GJI0 | nrdG | Ribonucleoside-triphosphate reductase activating | ||

| 24 | A0A0G9GKX1 | GNAT family acetyltransferase | |||

| 25 | A0A0G9GR36 | Transcriptional regulator | |||

| 26 | A0A0G9GTJ1 | Transcriptional regulator | |||

| 27 | A0A0G9GU14 | ABC.CD.P | ABC transporter permease | ||

| 28 | A0A0G9GU74 | murF | UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-tripeptide–D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase | ||

| 29 | A0A0G9GUG9 | GSR, gor | Glutathione reductase | ||

| 30 | A0A0L7XZK6 | PTS-Gut-EIIA, srlB | PTS system IIA component | ||

| 31 | A0A0M0CGA8 | Diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase | |||

| 32 | A0A0M0CHX3 | rsmC | Ribosomal RNA small subunit methyltransferase C | ||

| 33 | A0A0P7H5T1 | relA | GTP pyrophosphokinase | ||

| 34 | A0A0R1UDH2 | DUF2179 domain-containing | |||

| 35 | A0A0R1UU28 | NARS, asnS | Asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase | ||

| 36 | A0A0R1V3K0 | Trehalose operon transcriptional repressor | |||

| 37 | A0A0R1V4C9 | Branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter | |||

| 38 | A0A0R1V4X3 | patA | D-lactate dehydrogenase | ||

| 39 | A0A0R2G4A4 | Transcription regulator | |||

| 40 | A0A151G5A1 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| 41 | A0A151G5L5 | Lantibiotic epidermin biosynthesis | |||

| 42 | A0A162E1B4 | Nucleoside 2-deoxyribosyltransferase | |||

| 43 | A0A165P9S6 | ydjE | Niacin transporter | ||

| 44 | D7V8R3 | K06878 | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase domain | ||

| 45 | T5JD50 | gshA | Bifunctional glutamate–cysteine ligase | ||

| 46 | T5JD81 | Glutamine amidotransferase | |||

| 47 | T5JHA9 | K07009 | DegV family EDD domain-containing protein | ||

| 48 | T5JPL2 | ftsZ | Cell division protein FtsZ | ||

| 49 | U2WPC9 | Lactate oxidase | |||

bC: Co-cultivation of the luxS mutant strain with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207; D: Co-cultivation of the wild-type strain with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207.

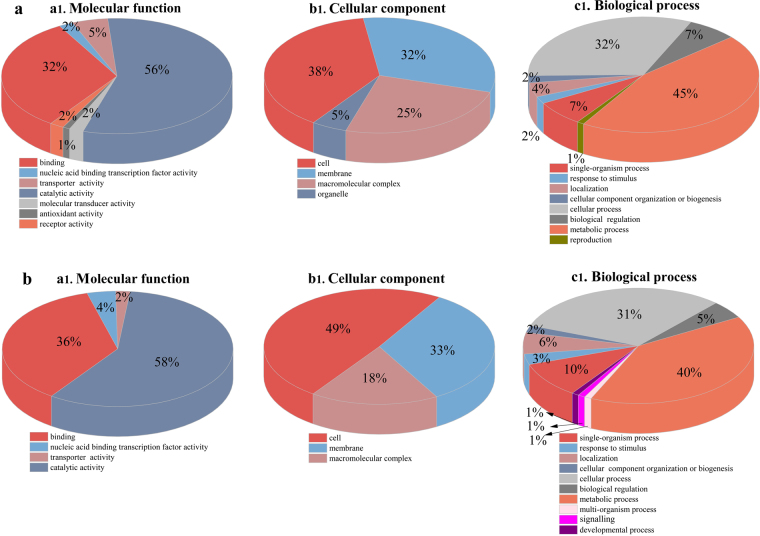

To characterize the set of proteins with decreased or increased expression for biological interpretation, gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed. The results of GO analysis showed that all identified differentially expressed proteins have different molecular functions and are involved in different cellular components; they also participate in different biological processes in the cell (Fig. 2). For the molecular function categories, all differentially expressed proteins were classified into seven functional groups in mono-cultivation but only into four groups in co-cultivation. The majority of the differentially expressed proteins in both mono- and co-cultivation conditions have catalytic activity or act as binding proteins (Fig. 2a[a1] and b[a1]). The cellular component ontology of proteins refers to the location in the cell where proteins are active17. Among these altered proteins, the majority in both groups are located in the cell, membrane, and macromolecular complexes, whereas differentially expressed proteins in organelles were only found in mono-cultivation (Fig. 2a[b1] and b[b1]). The altered proteins participate in a wide range of biological processes, such as metabolic, cellular, and single-organism processes (Fig. 2a[c1] and b[c1]).

Figure 2.

Map of gene ontology (GO) annotation. Classifications of all altered proteins in mono-cultivation (a) and co-cultivation (b), based on molecular function (a1), subcellular localization (b1), and biological process (c1).

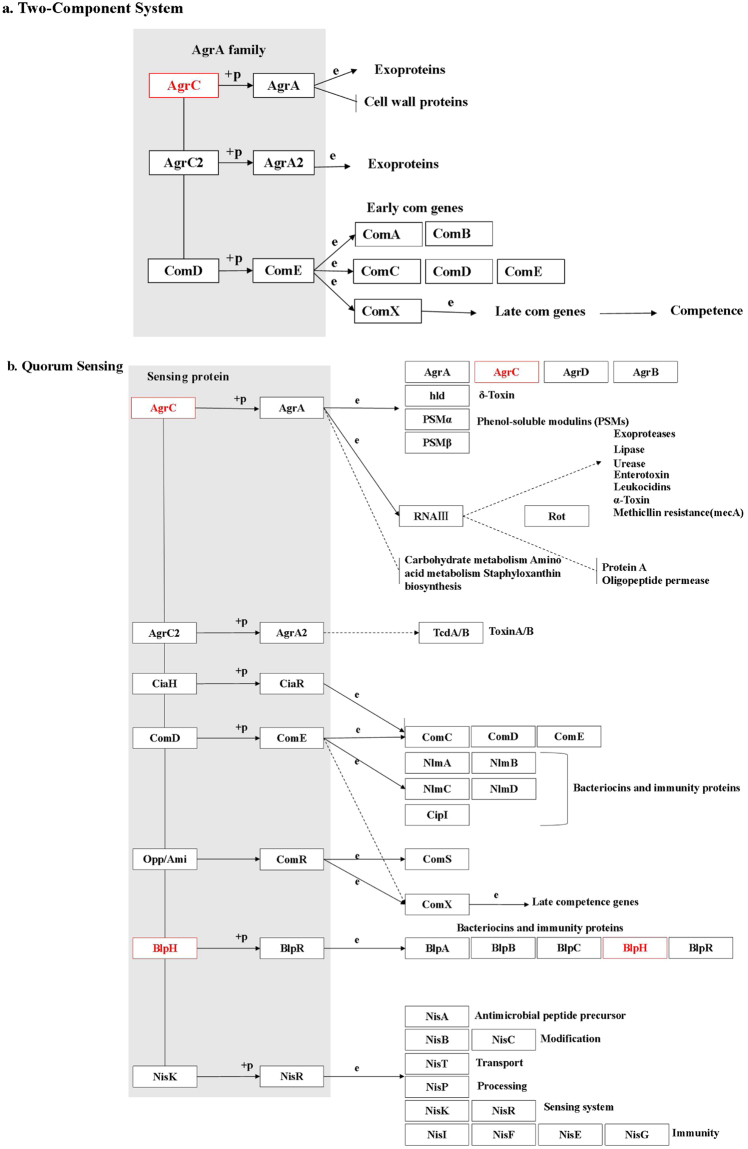

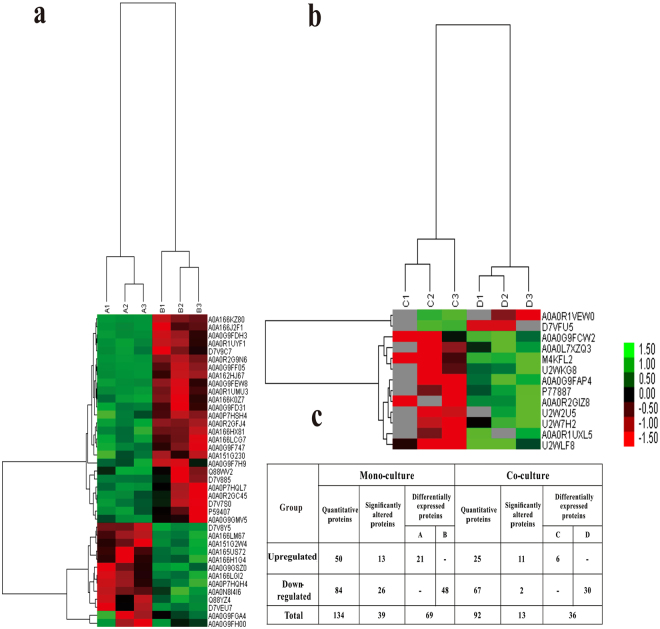

In addition, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotation for the co- (Fig. 3) and mono-cultivation groups (Supplementary Fig. S3) was analysed to delineate the effects of luxS on the networks of related molecules in bacteriocin biosynthesis. Figure 3 shows that the expression of the sensor histidine kinases ArgC and BlpH (two-component system) belonging to the LytTR family changed significantly (P < 0.01) upon co-cultivation. The LytTR domain is a DNA-binding domain that functions to activate or inhibit the transcription of a particular gene18; thus, it may activate the transcription of the gene encoding bacteriocin6. In contrast, the expression of proteins associated with bacteriocin synthesis involved in the QS and two-component system pathways did not change during mono-cultivation (Table 1), although the expression of ABC.PE.S protein, which is related to virulence or biofilm formation and is involved in QS and two-component system pathways, was altered in mono-cultivation (Supplementary Fig. S3). Clustering analysis showed high repeatability among three biological replicates, regardless of the cultivation group. Moreover, the protein expression between L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 wild-type and luxS mutant strains obviously differed in each cultivation group (Fig. 4a and b). In addition, a larger number of altered proteins were identified in the mono-cultivation group than in the co-cultivation group when the luxS gene was deleted (Fig. 4c).

Figure 3.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway for biosynthesis of bacteriocin [(a) two-component system, (b) quorum sensing]. Red represents proteins with decreased expression in L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 co-cultivated with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 on the graphic pathway map when luxS was deleted. Objects:  gene product, mostly protein but including RNA; Arrows:

gene product, mostly protein but including RNA; Arrows:  molecular interaction or relation; Protein-protein interactions:

molecular interaction or relation; Protein-protein interactions:  phosphorylation,

phosphorylation,  activation,

activation,  inhibition,

inhibition,  indirect effect,

indirect effect,  binding/association,

binding/association,  complex; Gene expression relation:

complex; Gene expression relation:  expression,

expression,  indirect effect.

indirect effect.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of obviously altered proteins in mono-cultivation (a) and co-cultivation (b). A1, A2, A3- L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 luxS mutant strain; B1, B2, B3- L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 wild-type strain; C1, C2, C3- KLDS1.0391 luxS mutant strain co-cultivated with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207; D1, D2, D3- KLDS1.0391 wild-type strain co-cultivated with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207. Up- and downregulated proteins are indicated in shades of green (increased) and red (decreased), respectively. (c) Number of differential proteins. ‘−’ indicates that protein expression was lower than the detection limit of MS.

Validation of the identified proteins

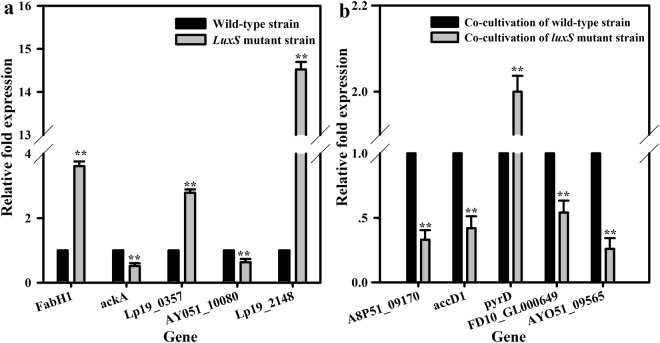

We chose 10 proteins from among those differentially expressed in mono-cultivation (i.e. FabH1, ackA, Lp19_0357, AY051_10080, and Lp19_2148) and co-cultivation (A8P51_09170, accD1, pyrD, FD10_GL000649, and AY051_09565) for subsequent validation by quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The relative fold expression of these identified proteins in the luxS mutant strain was significantly changed (all P < 0.01) compared to that in the wild-type strain in mono-cultivation and co-cultivation (Fig. 5). At the gene transcription level, the expression patterns of all 10 proteins corroborated the proteomic results.

Figure 5.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of gene expression of altered proteins in mono-cultivation of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 [(a) including five altered proteins] and co-cultivation of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 [(b) including five altered proteins] upon luxS knockout. **Statistically significant difference between L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 wild-type strain and luxS mutant strain (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Understanding the mechanism of QS regulation is indispensable to increasing our basic knowledge regarding environmental adaptation and improving the application of bacteria in the food industry19, especially when involving strategies for regulating QS in bacteriocin production. To illustrate the effects of luxS on bacteriocin production, we previously constructed a luxS mutant strain of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 by homologous recombination and found that AI-2 activity of the luxS mutant strain was significantly lower (P < 0.01) than that of the wild-type strain during a 4–24-h growth period (unpublished data), regardless of mono-cultivation or co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207. This suggested that the luxS gene is necessary for the synthesis of AI-2 by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391. Moreover, we also found that the bacteriocin production and AI-2 activity in L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 are positively correlated6. In the present study, the bacteriocin production by and cell number of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 were positively correlated during the logarithmic growth phase; this finding is consistent with that of cell population density-dependent regulation in QS5. Notably, the luxS gene had a large influence on cell number and bacteriocin production during co-cultivation but had no influence on these measures in mono-cultivation, as previously reported by Sztajer et al.20. This phenomenon revealed that the AI-2 signal export and reception/transduction pathways might differ between mono- and co-cultivation, resulting in bacteriocin production being ultimately sensitive to co- but not mono-cultivation. As shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S3, the results of the proteomic analyses are consistent with the above results. In particular, in response to luxS deletion in L. plantarum KLDS1.0391, the expression level of proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, fatty acid synthesis and metabolism, and the two-component regulatory system changed (Tables 1 and 2).

In co-cultivation, 3-oxoacyl ACP reductase (FabG) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase carboxyl transferase subunit beta (accD), which are related to fatty acid synthesis, were at levels lower than the detection limit of MS in the luxS mutant strain, whereas these proteins were abundant in the wild-type strain. FabG is positively related to the synthesis of fatty acids and catalyses the conversion of 3-ketoacyl ACP to 3-hydroxyacyl ACP21. In turn, AccD can catalyse the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA and is also the rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid synthesis22. These results indicate that the luxS deletion in L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 decreased the synthesis of fatty acids in this bacterium, which constitute the main component of the cell membrane. Bacteria can regulate cell membrane fluidity by regulating the type and composition of fatty acids, thereby maintaining membrane stability and normal physiological function; they can also adapt to different stresses23, such as acid stress24, heat shock25, bile stress26, and osmotic stress27. Thus, our findings suggest that the growth and metabolism of the luxS mutant strain decreased because of the reduction in the amount of fatty acids synthesized, which would impair KLDS1.0391 cell membrane fluidity.

In comparison, the presence of the phosphotransferase system (PTS) in L. plantarum is related to sugar catabolism and may facilitate this activity28 as well as the growth of L. plantarum. The low expression of the glucitol/sorbitol-specific IIA component (PTS, srlB) suggested that deletion of luxS might affect the growth of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391. Furthermore, in the present study, the expression of aminotransferase (patA), which participates in amino acid synthesis and is positively correlated with the biosynthesis of amino acids, was below the MS detection limit in the luxS mutant strain. Notably, previous studies investigating the stimulation of bacteriocin production by organic nitrogen sources29 have shown that certain amino acids are necessary to synthesize the lanthionine ring (only in lantibiotics)30, that several amino acids (or peptides) act as enzymatic inducers31, and that normal bacterial growth has specific nutritional requirements32. Although these results are unclear, and the specific role of amino acids in bacteriocin production has not yet been satisfactorily identified, amino acids (or peptides) are assumed to be involved in bacteriocin biosynthesis. Thus, our finding of decreased patA expression might represent one of the causes of altered bacteriocin production in the absence of the luxS gene. However, the effect of amino acids on bacteriocin synthesis requires further investigation.

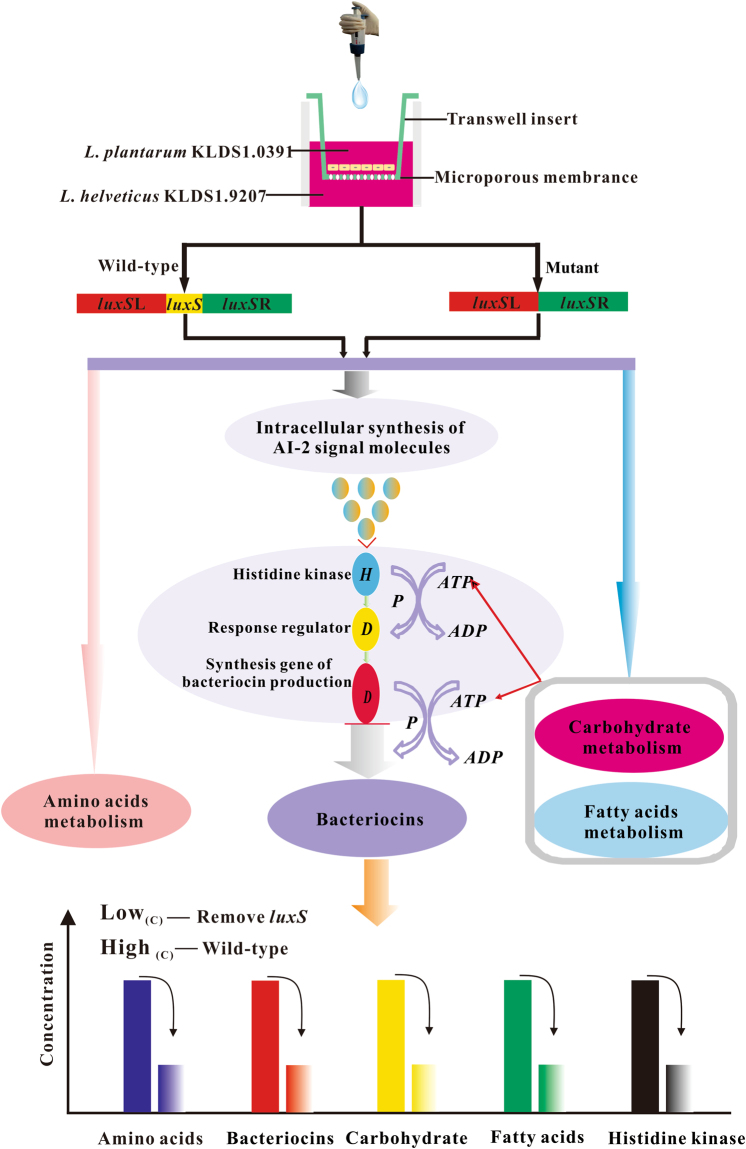

The two-component regulatory systems that recognize AI-2 and oligopeptide signalling molecules in LAB are consistent with each other33. The histidine protein kinase serves as a membrane-localised receptor or sensor for signalling molecules and transfers this signal through a series of phosphorylation or dephosphorylation reactions to the cytoplasmic response regulator, which in turn binds DNA to activate transcription of the bacteriocin synthesis gene33. In the present study, the levels of sensor histidine kinases (AgrC, BlpH), which are necessary for the subsequent induction of bacteriocin production34, were lower than the detection limit of MS in the luxS mutant strain, whereas these were abundant in the wild-type strain (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Several previous studies35,36 found that co-cultivation of L. acidophilus, L. sanfranciscensis CB1, and L. plantarum DC400 could increase bacteriocin production and that energy-metabolism-related proteins are also upregulated. As the biosynthesis of bacteriocin is generally considered a process of energy dissipation, we speculated that bacteriocin production might be associated with energy production in the carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolic pathways, and that a large amount of energy would be utilised by the two-component system to further control bacteriocin synthesis. These phenomena may also decrease the bacteriocin production in the luxS mutant strain. In combination with the phenotypic results, the possible mechanism of luxS function in bacteriocin biosynthesis during co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207, as inferred by our findings, is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Possible mechanism of LuxS in bacteriocin biosynthesis by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 in co-cultivation with L. helveticus KLDS1.9207. luxSL (1100 bp) and luxSR (1100 bp) represent the conserved left and right domains, respectively, of luxS.

During mono-cultivation, in response to the deletion of the luxS gene, L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 decreased the levels of proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism (e.g. pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha and beta subunits, pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 component, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase, and acetate kinase) and amino acid metabolism (e.g. dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase and phosphoserine aminotransferase). Without such deletion, L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 increased the level of 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase III (FabH) and decreased the level of enoyl-[acyl-carrier protein] reductase II (FabK), which are involved in fatty acid synthesis. Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha and beta subunits, as well as pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 component, are important constituent enzymes of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and are rate-limiting enzymes; they can also catalyse the irreversible oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. The oxidation of sugars, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation are related to acetyl-CoA, which plays an important role in mitochondrial respiratory chain energy metabolism37. The decrease in the level of pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha and beta subunits, as well as pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 component, showed that pyruvate was fermented to produce high amounts of lactic acid. Thus, L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 could accelerate the metabolic production of lactic acid in the absence of the luxS gene. In addition, the increase in FabH levels promoted fatty acid production, whereas the low level of FabK reduced fatty acid synthesis. These conflicting phenomena might lead to an unchanged metabolic capacity of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 upon luxS gene knockout. In our previous study, we found that when the bacteriocin of L. plantarum KLDS 1.0391 was separated and purified, its molecular weight was approximately 2,180 Da, and the sequence of its five N-terminal amino acids was valine-proline-tyrosine-proline-glycine14. Therefore, we speculated that the decrease in levels of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase and phosphoserine aminotransferase observed in the present study regulated the metabolism of glycine, serine, threonine, valine, leucine, and isoleucine; such decreases might also reduce bacteriocin production.

In summary, the results indicated that AI-2 signal export and reception/transduction pathways differed between mono- and co-cultivation of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391. Moreover, the carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and two-component regulatory system pathways of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 were altered when the luxS gene was deleted. Collectively, these pathways could influence the production of bacteriocin. In particular, carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism pathways may provide energy for bacteriocin biosynthesis through QS. Future research will focus on the specific role of amino acids in the bacteriocin production by L. plantarum KLDS1.0391. These findings will provide a theoretical foundation for the effect of luxS on bacteriocin production using selective culture conditions.

Methods

Bacterial strains, media, and growth

L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 (wild-type strain and luxS mutant strain), L. helveticus KLDS1.9207, and Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 were provided by the Dairy Industrial Culture Collection at the Key Laboratory of Dairy Science, China. L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 and L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 were grown in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth at 37 °C. The luxS mutant strain of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 contains chloramphenicol resistance genes, whereas the wild-type strain is sensitive to chloramphenicol. To prevent the luxS gene from recovering from the mutation and to restrain the growth of the wild-type strain, the luxS mutant strain was grown in MRS broth supplemented with chloramphenicol (10 μg/mL, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). B. subtilis ATCC6633 was grown in beef extract-peptone broth at 37 °C. All strains were stored at −80 °C in 40% (v/v) glycerol and propagated twice at 37 °C for 16 h in their corresponding broth medium before use.

Preparation of mono- and co-cultures

The tested extracts must be from a single strain to meet the requirements of proteomics analysis. All mono- and co-cultures were prepared as follows: 16-h-old cells of L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 wild-type and luxS mutant strains (approximately 109 colony forming units (CFU)/mL) were inoculated (1%, v/v) separately into fresh MRS and grown at 30 °C for 6 h (mid-exponential phase of growth) to obtain mono-cultures. To identify the differential expression of proteins in a co-culture system, co-cultures were prepared in a way similar to that reported by Di Cagno et al.12. In the present study, a chamber was used to realize the exchange of small molecules under the co-culture system and ensure that the tested strains were pure. A structural model of the chamber is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Chambers containing fresh MRS broth were inoculated with 1% of an overnight culture of the wild-type or luxS mutant strain in the culture insert, followed by 0.5% of an overnight culture of the co-culture strain (i.e. approximately 108 CFU/mL of L. helveticus KLDS1.9207 in the well); these chambers were then placed into an incubator at 30 °C for 6 h with gentle agitation (60 rpm). Co-cultivation was obtained from a double culture vessel apparatus separated by a 0.4-μm membrane filter (Millipore Isopore; Billerica, MA, USA). Each experiment was conducted in triplicate. Detection of membrane permeability and bacterial growth in the double chamber is shown in Supplementary S-1 (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S2).

Detection of live cell number and antibacterial activity

Co- and mono-cultivation were performed in MRS broth at 37 °C for 24 h, and samples of the culture were removed every 2 h to determine the live cell number by plate counting6. The antibacterial activities were analysed for each group using the modified ‘agar-well-diffusion-assay’ method38 with B. subtilis ATCC6633 as the indicator strain. The mono- and co-cultures of the wild-type strain were used as the positive controls for the assays of antibacterial activity. Inhibition zone diameter was used to indicate the antibacterial activity of bacteriocin6,38. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Extraction, quantification, and digestion of whole-cell proteins

Each culture was harvested (10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), re-suspended in 500 μL SDT-lysis buffer (4% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.6)39, boiled for 10 min, subjected to ultrasonic disruption (10 × 10 sec−1 pulses at 100 W, with 15 sec−1 intervals), and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and the proteins were quantified. The protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. SDS-PAGE was performed to verify the protein quality and concentration. Digestion of protein (100 μg for each sample) was performed according to the filter-aided-sample-preparation procedure described by Wiśniewski et al.39 with modifications. The detailed protocol is described in Supplementary S-2.

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem MS analysis

The peptide mixture of each sample was separated on a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (EASY-nLC 1000, Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA, USA). After HPLC separation, the peptides from all replicates were analysed using a Q-Exactive MS (Thermo Finnigan) for 120 min40,41. Notably, each sample was processed three times, and the MS experiments for each sample were performed in triplicate to avoid contingency of the date and assure data reliability. The liquid chromatographic conditions, elution gradient, and Q-Exactive MS requirements are described in Supplementary S-3.

Data analysis

Maxquant software version 1.3.0.5 was used to analyse the original data obtained from the label-free quantification proteome study for peptide identification and protein quantification42. The MS experimental data were searched against Unipro-Lactobaci-55542 -20160803.fasta.database (Indexed sequence 55542, downloaded on 03-08-2016). The main parameters used for protein identification and quantitative analysis are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The abundances of the peptides occurring in all control and experimental groups were compared by one-way ANOVA, and the proteins listed were filtered based on the ratio >±2 and P value < 0.0542.

Bioinformatics analysis

GO, KEGG pathway, and clustering enrichment analyses were performed. All the identified differential proteins were submitted to GO analysis using Blast2GO43. The identified differential protein sequences were blasted against the NCBI database (ncbi-blast-2.2.28 + -win32.exe), and the first 10 alignment sequences that satisfied E-value ≤ 1e−3 were reserved for subsequent analysis. The GO entries associated with the target protein set and the matched alignment sequences in step one were extracted using the Blast2GO Command Line (database version: go_201504.obo, download address: www.geneontology.org). KEGG Automatic Annotation Server software was used to classify the target protein sequences into KEGG orthology (KO) by comparison with the KEGG GENES database44, and the path information of the target protein sequences were obtained automatically in accordance with KO classification. An average linkage hierarchical clustering analysis of samples based on the Euclidean distance algorithm was implemented in Cluster3.0 (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm) and the Java Treeview software (http://jtreeview.sourceforge.net).

Validation by qRT-PCR

FabH1, ackA, Lp19_0357, AY051_10080, Lp19_2148, A8P51_09170, accD1, pyrD, FD10_GL000649, and AY051_09565 are involved in fatty acid metabolism, pyruvate metabolism, pyrimidine metabolism, amino acids, and the two-component regulatory system. Thus, they were chosen to determine the level of gene transcription by qRT-PCR and validate the results of proteomics. RNA isolation and distinct expression analysis of the 10 mRNAs were implemented by a modified version of the method described by Man et al.6. RNA isolation was implemented using an RNAprep Pure Bacteria Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China), as recommended by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript® RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China), as described by the manufacturer. qRT-PCR amplification and detection were performed using the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the Sybr® Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara), following the protocol supplied.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data generated from the current study are available and have been deposited in iProX database (http://www.iprox.org/page/PDV014.html?projectld=IPX0001032000).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Outstanding Youth Scientists Foundation of Harbin City (2014RFYXJ006) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31671917). The authors thank Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Co., Ltd. for providing technical support and the proof-readers and editors for their thoughtful suggestions and insights.

Author Contributions

J.F.F. and M.X.C. designed and conducted the study; prepared the samples; detected the live cell number and antibacterial activity; extracted, quantified, and digested the whole-cell protein; analysed the data; prepared Figures 1–4 and the tables; and wrote the main manuscript text. P.X.H. and Z.D.X. validated the identified proteins and suggested data analysis methods. Z.Z.T. and S.S.R. prepared Figures 5–6 and supervised the analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13231-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stiles ME. Biopreservation by lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:331–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00395940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diep DB, Nes IF. Ribosomally synthesized antibacterial peptides in gram positive bacteria. Curr. Drug Targets. 2002;3:107–122. doi: 10.2174/1389450024605409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eijsink VG, et al. Production of class II bacteriocins by lactic acid bacteria; an example of biological warfare and communication. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002;81:639–654. doi: 10.1023/A:1020582211262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sturme MH, Francke C, Siezen RJ, de Vos WM, Kleerebezem M. Making sense of quorum sensing in lactobacilli: a special focus on Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Microbiology. 2007;153:3939–3947. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams P, Winzer K, Chan WC, Cámara M. Look who’s talking: communication and quorum sensing in the bacterial world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2007;362:1119–1134. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Man LL, Meng XC, Zhao RH, Xiang DJ. The role of plNC8HK-plnD genes in bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391. Int. Dairy J. 2014;34:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2013.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma YP, et al. luxS/AI-2 Quorum sensing is involved in antimicrobial susceptibility in Streptococcus agalactiae. Fish Pathol. 2015;50:8–15. doi: 10.3147/jsfp.50.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maldonado-Barragán A, Caballero-Guerrero B, Lucena-Padrós H, Ruiz-Barba JL. Induction of bacteriocin production by coculture is widespread among plantaricin-producing Lactobacillus plantarum strains with different regulatory operons. Food Microbiol. 2013;33:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira CS, Thompson JA, Xavier KB. AI-2-mediated signalling in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013;37:156–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun J, Daniel R, Wagner-Döbler I, Zeng AP. Is autoinducer-2 a universal signal for interspecies communication: a comparative genomic and phylogenetic analysis of the synthesis and signal transduction pathways. BMC Evol. Biol. 2004;4:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chanos P, Mygind T. Co-culture-inducible bacteriocin production in lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;100:4297–4308. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Cagno R, De Angelis M, Coda R, Minervini F, Gobbetti M. Molecular adaptation of sourdough Lactobacillus plantarum DC400 under co-cultivation with other Lactobacilli. Res. Microbiol. 2009;160:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tannock GW, et al. Ecological behavior of Lactobacillus reuteri 100-23 is affected by mutation of the luxS gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:8419–8425. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8419-8425.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong HS, Meng XC, Wang H. Mode of action of plantaricin MG, a bacteriocin active against Salmonella typhimurium. J. Basic Microbiol. 2010;50:S37–45. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong HS, Meng XC, Wang H. Plantaricin MG active against Gram-negative bacteria produced by Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391 isolated from “Jiaoke”, a traditional fermented cream from China. Food Control. 2010;21:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2009.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Man LL, Meng XC, Zhao RH. Induction of plantaricin MG under co-culture with certain lactic acid bacterial strains and identification of LuxS mediated quorum sensing system in Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391. Food Control. 2012;23:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waters CM, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;21:319–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sztajer H, et al. Autoinducer-2-regulated genes in Streptococcus mutans UA159 and global metabolic effect of the luxS mutation. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:401–415. doi: 10.1128/JB.01086-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng J, et al. Only one of the five Ralstonia solanacearum long-chain 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase homologues functions in fatty acid synthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:1563–1573. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07335-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakkaew A, Chotigeat W, Eksorntramae T, Phongdara A. Cloning and expression of a plastid-encoded subunit, beta-carboxyltransferase gene (accD) and a nuclear-encoded subunit, biotin carboxylase of acetyl-CoA carboxylase from oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) Plant Sci. 2008;175:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang YM, Rock CO. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:222–233. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broadbent JR, Larsen RL, Deibel V, Steele JL. Physiological and transcriptional response of Lactobacillus casei ATCC 334 to acid stress. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:2445–2458. doi: 10.1128/JB.01618-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broadbent JR, Lin C. Effect of heat shock or cold shock treatment on the resistance of Lactococcus lactis to freezing and lyophilization. Cryobiology. 1999;39:88–102. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1999.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koskenniemi, K. et al. Proteomics and transcriptomics characterization of bile stress response in probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Mol. Cell Proteomics10, M110.002741 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Guillot A, Obis D, Mistou MY. Fatty acid membrane composition and activation of glycine-betaine transport in Lactococcus lactis subjected to osmotic stress. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000;55:47–51. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleerebezem M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA. 2003;100:1990–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337704100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vázquez JA, Cabo ML, González MP, Murado MA. The role of amino acids in nisin and pediocin production by two lactic acid bacteria: A factorial study. Enzyme Microbiol. Technol. 2004;34:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2003.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozak W, Bardowski J, Dobrzański W. Lacstrepcin-a bacteriocin produced by Streptococcus lactis. Bull. Acad. Pol. Sci. Biol. 1977;25:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen PR, Hammer K. Minimal requirements for exponential growth of Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993;59:4363–4366. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4363-4366.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aasen IM, Møretrø T, Katla T, Axelsson L, Storrø I. Influence of complex nutrients, temperature and pH on bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus sakei CCUG 42687. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000;53:159–166. doi: 10.1007/s002530050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum Sensing in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diep DB, Håvarstein LS, Nes IF. Characterization of the locus responsible for the bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:4472–4483. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4472-4483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azcarate-Peril MA, et al. Microarray analysis of a two-component regulatory system involved in acid resistance and proteolytic activity in Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:5794–5804. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5794-5804.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Cagno R, et al. Quorum sensing in sourdough Lactobacillus plantarum DC400: induction of plantaricin A (PlnA) under co-cultivation with other lactic acid bacteria and effect of PlnA on bacterial and Caco-2 cells. Proteomics. 2010;10:2175–2190. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel MS, Korotchkina LG. Regulation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST0340217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schillinger U, Lücke FK. Antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus sake isolated from meat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1989;55:1901–1906. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.8.1901-1906.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen S, Luo Y, Ding G, Xu F. Comparative analysis of Brassica napus plasma membrane proteins under phosphorus deficiency using label-free and MaxQuant-based proteomics approaches. J. Proteomics. 2016;133:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, et al. Degradation of swainsonine by the NADP-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase A1R6C3 in arthrobacter sp. hw08. Toxins (Basel) 2016;8:E145. doi: 10.3390/toxins8050145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Götz S, et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D109–114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data generated from the current study are available and have been deposited in iProX database (http://www.iprox.org/page/PDV014.html?projectld=IPX0001032000).