ABSTRACT

Aspergillus fumigatus is the main species responsible for aspergillosis in humans. The diagnosis of aspergillosis remains difficult, and the rapid emergence of azole resistance in A. fumigatus is worrisome. The aim of this study was to validate the new MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit and to evaluate its performance on clinical samples for the detection of A. fumigatus and its azole resistance. This multiplex assay detects DNA from the A. fumigatus species complex by targeting the multicopy 28S rRNA gene and specific TR34 and L98H mutations in the single-copy-number cyp51A gene of A. fumigatus. The specificity of cyp51A mutation detection was assessed by testing DNA samples from 25 wild-type or mutated clinical A. fumigatus isolates. Clinical validation was performed on 88 respiratory samples obtained from 62 patients and on 69 serum samples obtained from 16 patients with proven or probable aspergillosis and 13 patients without aspergillosis. The limit of detection was <1 copy for the Aspergillus 28S rRNA gene and 6 copies for the cyp51A gene harboring the TR34 and L98H alterations. No cross-reactivity was detected with various fungi and bacteria. All isolates harboring the TR34 and L98H mutations were accurately detected by quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis. With respiratory samples, qPCR results showed a sensitivity and specificity of 92.9% and 90.1%, respectively, while with serum samples, the sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 84.6%, respectively. Our study demonstrated that this new real-time PCR kit enables sensitive and rapid detection of A. fumigatus DNA and azole resistance due to TR34 and L98H mutations in clinical samples.

KEYWORDS: Aspergillus fumigatus, molecular diagnosis, azole resistance, cyp51A, TR34 L98H

INTRODUCTION

Accurate diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in patients at high risk of invasive fungal infection remains challenging (1, 2) due to difficulties in differentiating IPA from pulmonary infections caused by other molds or bacteria on clinical and radiological grounds. Therefore, culture-based microbiological diagnosis is of primary importance but requires semi-invasive or invasive procedures, such as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or computed-tomography (CT)-guided needle biopsy (3, 4). Alternate diagnostic methods include the detection of biomarkers, such as fungal antigens (Aspergillus galactomannan [GM]) or DNA released by Aspergillus hyphae in host tissues (3, 4). These biomarkers are well recognized as early IPA predictors (5–7). Recently, several clinical evaluations to detect Aspergillus DNA, either in respiratory or in blood-based samples, have clearly shown the diagnostic value of this biomarker (4–9). In addition, methodological recommendations have been established for PCR protocols (10), and different standardized Aspergillus quantitative PCR (qPCR) kits have been commercialized (11, 12). These recent advances show that PCR is now mature for routine use in clinical settings.

Another issue is the emergence of aspergillosis due to azole-resistant isolates. Acquired azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus has been reported since 1997 (13–16) and has emerged in many countries, particularly in Europe (17–22), as well as on other continents (23–26). In some instances, acquired resistance may be driven by antifungal selection in patients receiving long-term therapy (27). Nevertheless, it seems that many azole-resistant strains originated in the environment due to selection by azole fungicides used in agriculture (28). Azole resistance in A. fumigatus is associated mainly with mutations in the cyp51A gene, and among several mutations described, the most frequent is the mutation comprising a 34-bp tandem repeat (TR34) and the L98H alteration.

Since azoles are the recommended first-line treatment for IPA (29), the emergence of azole resistance is worrisome and has been shown to be associated with an increased rate of clinical failure (30). For these reasons, routine antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) of clinical isolates has been recommended recently (31). Nevertheless, isolates are not always retrieved in culture, particularly for patients with hematological malignancies (1). Therefore, molecular detection of resistance may be a major advance for the management of patients with invasive aspergillosis (IA).

In this context, some assays have been developed to enable the detection of both A. fumigatus DNA and cyp51A mutations associated with azole resistance in clinical samples (32, 33). Only one kit has been evaluated recently with either respiratory (32, 34) or serum (33) samples.

In the present study, a new CE-IVD (In Vitro Diagnostics)-compliant multiplex real-time qPCR assay has been designed, optimized, and validated.

(This work has been presented in part at the 25th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases [ECCMID], Copenhagen, Denmark, 25 to 28 April 2015.)

RESULTS

Analytical performance of the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit. (i) Sensitivity and specificity.

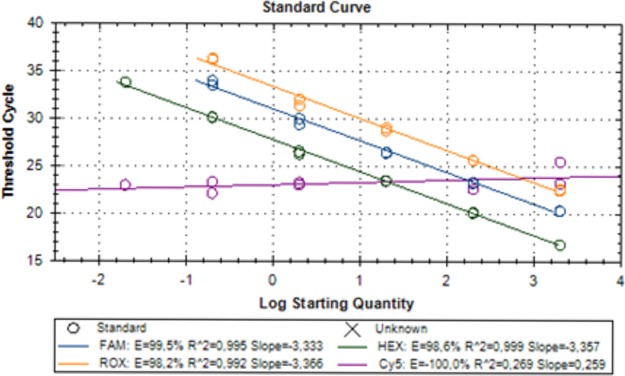

The limit of blank (LoB) for the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit was fixed at 40 cycles. The limit of detection (LoD) for the cyp51A gene harboring the TR34 and L98H mutations (a single-copy-number gene) was determined at 6 copies, while the LoD for the Aspergillus 28S rRNA gene (a highly repetitive gene) was <1 copy (verified with five clinically mutated isolates and one wild-type isolate). As shown in Fig. 1, the detection of both mutations in the single-copy-number cyp51A gene was not affected by the amplification of the A. fumigatus-specific 28S rRNA multicopy gene.

FIG 1.

Analytical performance of the MycoGENIE real-time PCR. The efficiency and dynamic range of the PCR are shown.

No cross-reactivity was detected when qPCR was performed with DNA from Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus versicolor, Aspergillus terreus, Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, Candida lusitaniae, Penicillium spp., Fusarium spp., Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

The specificity of cyp51A mutation detection was assessed by testing DNA samples from 25 wild-type or mutated (TR34 L98H, TR46 Y121F T289A) clinical A. fumigatus isolates (Table 1). All isolates harboring the TR34 L98H mutations (10/25) were accurately detected by qPCR.

TABLE 1.

Detection of TR34 L98H cyp51A mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates by the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus qPCR assay

| Isolate | Mutations (detected by PCR/sequencing) |

CT by qPCRa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR34 | A. fumigatus | L98H | ||

| 1 | 23.47 | |||

| 2 | 20.72 | |||

| 3 | TR34 L98H | 23.56 | 20.89 | 24.49 |

| 4 | TR46 Y121F T289A | 20.64 | ||

| 5 | 20.57 | |||

| 6 | TR46 Y121F T289A | 20.61 | ||

| 7 | TR34 L98H | 22.93 | 20.39 | 24.06 |

| 8 | 21.41 | |||

| 9 | TR34 L98H | 23.74 | 21.35 | 24.80 |

| 10 | TR34 L98H | 23.45 | 20.61 | 24.43 |

| 11 | TR46 Y121F T289A | 20.87 | ||

| 12 | 21.22 | |||

| 13 | 20.87 | |||

| 14 | TR34 L98H | 23.06 | 20.46 | 24.21 |

| 15 | TR34 L98H | 23.02 | 20.59 | 24.15 |

| 16 | 21.74 | |||

| 17 | 21.36 | |||

| 18 | TR34 L98H | 23.77 | 21.18 | 24.92 |

| 19 | TR46 Y121F T289A | 20.97 | ||

| 20 | 21.08 | |||

| 21 | TR34 L98H | 23.35 | 20.37 | 24.13 |

| 22 | 20.15 | |||

| 23 | TR34 L98H | 22.67 | 20.28 | 23.73 |

| 24 | TR34 L98H | 23.21 | 20.63 | 24.36 |

| 25 | TR46 Y121F T289A | 21.18 | ||

CT, threshold cycle.

The performance of the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit was also validated using the Aspergillus DNA Calibrator (35), which was purified from strain AF293 using limiting-dilution analysis (35). Starting from the concentrated calibration solution (1.73E+6 U/ml), 10 replicates of 10-fold serial dilutions were quantified using the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit, and an LoD of 65 U/ml was reported.

(ii) Repeatability and reproducibility.

Reproducibility was determined by four different operators testing four-point serial dilutions of synthetic DNA in triplicate. The synthetic DNA contains all the sequences targeted by the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit. Experiments were performed using a single batch from the qPCR kit on a CFX96 qPCR instrument. The mean standard deviation and coefficient of variation (CV) were 0.25 and 0.9%, respectively.

Repeatability was assessed with serial dilutions of DNA from mutated clinical isolates. Each point was quantified 20 times. The LoD was determined at 6 copies for the TR34 and L98H mutations, with a mean standard deviation and CV of 0.75 and 2.18%, respectively.

Clinical evaluation. (i) Respiratory samples.

Among the 88 respiratory samples (from 62 patients), 59 were culture positive for Aspergillus species (51 with A. fumigatus and 8 with Aspergillus species other than A. fumigatus), 11 grew other fungi, and 18 were culture negative (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Five BAL fluid samples found negative for A. fumigatus by culture were positive for GM. Therefore, 56 samples were considered positive for A. fumigatus, and 32 samples were considered negative. qPCR results were positive for 55 samples and negative for 33 samples, indicating an overall sensitivity and specificity of 92.9% and 90.1%, respectively (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Concordance between qPCR and classical mycology for respiratory samples

| Mycology for A. fumigatusa | No. of samples with the following qPCRb result: |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 52 | 4 | 56 |

| Negative | 3 | 29 | 32 |

| Total | 55 | 33 | 88 |

Includes positive culture and/or positive GM by BAL.

Sensitivity, 92.9% (52/56); specificity, 90.1% (29/32).

(ii) Serum samples.

For the 16 patients with proven or probable IA, all 16 serum samples obtained at the time of diagnosis (±2 days) were qPCR positive (Table 3). Among the 13 individuals without IA, there were 10 healthy individuals and 3 patients with hematological malignancies. Of these three patients, two had fungal infections other than aspergillosis (hepatosplenic candidiasis; fungemia due to Magnusiomyces capitatus) and one had no fungal infection. Eleven of the 13 serum samples tested were qPCR negative, while 2 serum samples from 2 patients without IA tested qPCR positive, corresponding to the 2 false-positive DNA detection cases. Overall, the sensitivity and specificity of A. fumigatus qPCR were 100% and 84.6%, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Performance of the MycoGENIE qPCR assay for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis from serum samples

| Result by MycoGENIE qPCRa | No. of patientsb |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IA | Non-IA | Total | |

| Positive | 16 | 2 | 18 |

| Negative | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 16 | 13 | 29 |

At the time of diagnosis. MycoGENIE qPCR had a sensitivity of 100% (16/16) and a specificity of 84.6% (11/13).

One serum sample per patient.

Comparison between the MycoGENIE procedure and the reference procedure.

For 30 samples (19 serum and 11 respiratory samples), the MycoGENIE procedure (extraction from 200 μl of the sample and qPCR) was compared to a validated in-house procedure (a large extraction volume [1 ml of the sample] and qPCR) (7), considered as a reference procedure, using the same DNA target (Table 4). Among the 30 samples, 18 were positive and 12 were negative by the reference qPCR, and in all cases, the MycoGENIE qPCR gave identical results, indicating 100% concordance between the two qPCR techniques.

TABLE 4.

Comparison between MycoGENIE and an in-house reference procedurea

| Sample ID | Sample type | qPCR result (CT) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| In-house | MycoGENIE | ||

| N1 | Serum | − | − |

| N2 | Serum | − | − |

| N3 | Serum | − | − |

| N4 | Serum | − | − |

| N5 | Serum | − | − |

| N6 | Serum | − | − |

| N7 | Serum | − | − |

| N8 | Serum | − | − |

| N9 | Serum | − | − |

| N10 | Serum | − | − |

| S1 | Serum | + (34.9) | + (38.5) |

| S2 | Serum | + (29) | + (32.9) |

| S3 | Serum | + (34.6) | + (36) |

| S4 | Serum | + (32.2) | + (34.6) |

| S5 | Serum | + (36.7) | + (36.5) |

| S6 | Serum | + (34.1) | + (35.4) |

| S7 | Serum | + (38.8) | + (38.3) |

| S8 | Serum | + (38.2) | + (37.7) |

| S9 | Serum | + (31.6) | + (34.4) |

| P11 | Respiratory | + (28.3) | + (26.2) |

| P12 | Respiratory | + (31.3) | + (29.1) |

| P13 | Respiratory | + (26.6) | + (27.4) |

| P15 | Respiratory | + (33.2) | + (35.6) |

| P16 | Respiratory | + (29.2) | + (30.7) |

| P18 | Respiratory | + (30.1) | + (28.2) |

| P19 | Respiratory | − | − |

| P20 | Respiratory | + (29.3) | + (29.6) |

| P21 | Respiratory | + (26.4) | + (29.1) |

| P22 | Respiratory | + (34.7) | + (33.5) |

| P23 | Respiratory | − | − |

The in-house reference procedure included a large extraction volume (1 ml) using a MagnaPure kit, and qPCR was performed as published previously (7). The MycoGENIE procedure included a 200-μl extraction volume, and qPCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

DNA kinetic study.

For four patients with IA, serial serum samples (3 to 17 serum samples per patient) were available, and these were tested for both DNA and GM detection. For two patients, DNA was detected in the serum 5 days earlier than GM. For one patient, DNA and GM were detected concomitantly in the same sample, and for one patient, only positive samples for the two markers were available, precluding kinetic analysis.

DISCUSSION

It is well known, on the basis of several clinical studies, that detection of Aspergillus DNA in serum and/or BAL fluid is of great importance for the diagnosis of IA in immunocompromised patients (5). Nevertheless, the most recent guidelines have recommended that PCR should be used carefully for the management of patients, owing to the lack of validation of commercially available kits (36).

In this study, we present the results of the technical evaluation of a new standardized multiplex real-time A. fumigatus PCR kit, which allows detection of both A. fumigatus DNA, for IA diagnosis, and cyp51 mutations responsible for azole resistance. According to our results, this PCR kit showed good performance, including a low LoD for DNA detection and a lack of cross-reactivity with other pathogenic fungi. In addition, for the detection of the TR34 L98H mutation, azole-resistant isolates harboring different cyp51 mutations as well as wild-type isolates were tested, and this PCR kit showed very good specificity with no loss of efficiency.

Furthermore, the kit was evaluated using a large panel of clinical samples, either serum samples from patients with proven aspergillosis or BAL fluid specimens, which were previously characterized according to the gold-standard mycological methods.

With serum samples, both sensitivity and specificity were high (100% and 84.6%, respectively). This high sensitivity was reached by use of an optimized extraction volume of 200 μl, lower than the extraction volume (1 ml) of the reference method. By processing 5 times more sample volume and analyzing 15 μl of the eluate, the reference method should lead to better detection of A. fumigatus DNA (with a ΔCT close to 2.9) than the MycoGENIE procedure. Table 4 shows that in most cases (16/18), the MycoGENIE kit led to detection earlier than expected, with only a 200-μl sample, highlighting its more-efficient DNA extraction procedure. Indeed, the DNA extraction protocol was specifically optimized to process serum samples efficiently. The high yield of the extraction relies mainly on the magnetic particles used, which offer a very large specific area and enhanced binding kinetics thanks to their uniform surface and size. Thus, they can capture very small amounts of DNA from complex samples (37). Their performance is already well known in very demanding sample preparation applications, such as forensic science, where they are used in commercial kits designed for the recovery and purification of trace DNA from crime scenes (38). This remarkable performance is combined with a very low elution volume (<100 μl) to increase the DNA concentration. In addition, the 10-μl eluate used for qPCR analysis also contributes to improving the limit of detection of the assay.

With respiratory samples, sensitivity and specificity were 92.9% and 90%, respectively. The presence of free-circulating DNA in serum may explain the better efficiency of the extraction procedure in serum samples than in respiratory samples. Indeed, in respiratory samples, Aspergillus is present mainly in the hyphal form, for which DNA extraction is known to be more labor-intensive and less efficient.

Until now, only one other Aspergillus PCR kit (AsperGenius) combining the detection of Aspergillus DNA with the detection of cyp51 mutations associated with azole resistance has been evaluated (32–34).

The performance of the MycoGENIE kit appeared to be similar to that of the AsperGenius kit. With BAL fluid specimens from hematological and intensive-care-unit patients, the AsperGenius kit showed sensitivities of 88.9% and 80.0% and specificities of 89.3% and 93.3%, respectively (32). The sensitivity and specificity of the AsperGenius kit for serum samples were 78.6% and 100%, respectively.

In our study, no sample positive for the TR34 L98H mutations was detected. However, azole resistance has emerged during the past 15 years (39) and now seems to be a worldwide problem (22). For these reasons, we designed an Aspergillus qPCR assay to enable the detection of the TR34 L98H alterations in the cyp51 gene. These alterations constitute the most frequent mechanism of azole resistance in either clinical or environmental A. fumigatus isolates (22, 39). Although resistance is generally detected phenotypically, by AFST of isolates obtained in culture, molecular detection of resistance markers offers many advantages. First, detection of resistance may be obtained at the same time as the results of diagnostic PCR and may be more rapid than standard AFST when the strain is available. Second, in many clinical settings of aspergillosis, strains are not available, so direct detection of DNA-based resistance markers in tissues or in serum may be valuable. Overall, the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus kit could be a useful tool for the management of different populations of patients (oncohematology, lung transplantation, and cystic fibrosis).

To date, only two kits combine the detection of Aspergillus DNA with the detection of resistance markers. These kits allow the detection of only a restricted number of Cyp51A alterations (TR34 and L98H for the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus kit; TR34, L98H, Y121F, and T289A for the AsperGenius kit). Although several other Cyp51A mutations or mechanisms of azole resistance have been described, the TR34 L98H mutations have been reported as the most frequent (50%), according to a recent multicenter international study (22). Due to the limitations of real-time multiplex qPCR technology, only a restricted number of mutations can be efficiently detected simultaneously.

Our study is the first evaluation of the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus kit. This kit has been validated for both serum and respiratory samples. These results demonstrate the good performance of the kit. The MycoGENIE A. fumigatus kit enables sensitive and rapid detection of A. fumigatus DNA and azole resistance due to TR34 L98H alterations in clinical samples. Larger prospective studies with different groups of patients at high risk of IA are warranted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

The study was divided into two steps. The first step was performed to determine the analytical performance of the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit, including the limit of detection, cross-reactivity, sensitivity, specificity, repeatability, and reproducibility. The second step was clinical evaluation, consisting of kit validation using clinical serum and respiratory samples.

MycoGENIE procedure. (i) DNA extraction.

In all experiments, DNA was extracted from A. fumigatus isolates, sera, and respiratory samples according to the manufacturer's protocol, using the MycoGENIE DNA extraction kit for AutoMag solution (Ademtech, Pessac, France). The AutoMag instrument was used as an automated magnetic particle processor for DNA purification kits. It processes as many as 12 samples per run in a DNA extraction plate (a ready-to-use sealed 96-well plate) and includes reagents for lysis/capture, washing, and elution. For each extraction, 200 μl of sample and 10 μl of an internal control (IC) were added to the capture well. The IC was used to monitor the DNA extraction procedure and to detect PCR-inhibitory substances. After lysis/capture for 5 min, the DNA attached to the magnetic particles in the well was washed by three successive washing steps to remove unbound substances (proteins, cell debris, and PCR inhibitors). Following this, the elution step was performed in the heating well filled with 60 μl of elution buffer. DNA solutions were transferred to microtubes, directly processed for real-time PCR, and stored at −20°C for further analysis.

(ii) Real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR for the detection of A. fumigatus DNA was performed using the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit (Ademtech, Pessac, France) on a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad, USA). This multiplex assay specifically detects DNA from the A. fumigatus species complex by targeting the 28S rRNA multicopy gene and specific TR34 and L98H mutations in the A. fumigatus single-copy-number gene cyp51A.

Multiplex amplification reactions were carried out in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 12.5 μl of a UTP-containing master mix (2×), 10 μl of previously extracted DNA, and 2.5 μl of DNase- and RNase-free water. To avoid carryover contamination between PCRs, the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus mixture contains UDG (uracil-DNA glycosylase). After preincubation at 37°C for 10 min for UDG activation and at 95°C for 10 min for Taq activation, amplification was performed over 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and annealing/extension at 62°C for 45 s. Negative and positive controls were included in each assay. A positive control, with all targeted sequences, is provided in the MycoGENIE PCR kit to assess the integrity of the nucleic acid amplification assay. The IC reaction was considered inhibited for Cy5 signal results higher than 35 cycles.

Clinical samples. (i) Respiratory samples.

A total of 88 respiratory samples were obtained from 62 patients in two centers (Pellegrin University Hospital, Bordeaux, France, and Georges Pompidou European University Hospital, Paris, France). These comprised 51 BAL fluid, 23 sputum, and 14 bronchial fluid samples. Direct examination and culture of samples were routinely performed according to standard mycological methods (40). Filamentous fungi were identified phenotypically by macroscopic and microscopic observations (41). GM was detected in BAL fluid by the Platelia Aspergillus enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and samples were considered positive at an index value of ≥0.5. GM detection was not performed for respiratory samples other than BAL fluid. Samples were stored frozen at −20°C until further molecular analysis. qPCR results were compared to the results of culture and/or GM detection. A respiratory sample was considered positive for A. fumigatus if the culture yielded A. fumigatus and/or if the sample was positive for GM (for BAL fluid). A sample was considered negative for A. fumigatus if the culture was negative or if another mold was detected.

(ii) Serum samples.

A total of 55 serum samples from 16 patients with proven or probable aspergillosis (according to EORTC criteria) (42) in two centers (Pellegrin University Hospital, Bordeaux, France, and Necker University Hospital, Paris, France) were included. For five patients, serial serum samples were available (3 to 17 per patient) and were used to evaluate the kinetics of both GM and DNA detection. GM was detected in serum by the Platelia Aspergillus EIA (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fourteen serum samples from 13 patients without IA were included as negative controls.

The sensitivity and specificity of qPCR for IA diagnosis were evaluated using results obtained from serum samples at the time of IA diagnosis, defined as the day of initiation of curative antifungal treatment (±2 days), and serum samples from negative controls.

Comparison with a reference technique.

The performance of the MycoGENIE procedure (extraction and qPCR) was also evaluated by testing 19 serum samples (from 9 IA patients and 10 controls) and 12 respiratory samples concomitantly with a previously clinically validated in-house procedure (a large extraction volume for serum samples, 200 μl for respiratory samples, and qPCR) (7).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.G., G.L., L.A., and S.G. are employees of Ademtech SA. During the past 5 years, E.D. has received research grants from MSD and Gilead; travel grants from Gilead, MSD, Pfizer, and Astellas; and speaker's fees from Gilead, MSD, and Astellas. M.-E.B. has received research grants from MSD and Astellas; travel grants from Gilead, MSD, and Astellas; and speaker's fees from Gilead, MSD, and Astellas. P.E.V. participated in continuing-medical-education workshops with support from MSD and Gilead Sciences; he or his department received contributions for scientific research and consultancy services from Astellas, Basilea, Gilead Sciences, MSD, F2G, and Scynexis.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01032-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hope WW, Walsh TJ, Denning DW. 2005. Laboratory diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Lancet Infect Dis 5:609–622. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrosky-Zeichner L. 2012. Invasive mycoses: diagnostic challenges. Am J Med 125(Suppl):S14–S24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitis M, Anagnostou T, Fuchs BB, Caliendo AM, Mylonakis E. 2014. Molecular and nonmolecular diagnostic methods for invasive fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:490–526. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00091-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bougnoux ME, Lanternier F, Catherinot E, Suarez F, Lortholary O. 2011. Diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with hematologic diseases, p 327–336. In Azoulay E. (ed), Pulmonary involvement in patients with hematological malignancies. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvanitis M, Ziakas PD, Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Caliendo AM, Mylonakis E. 2014. PCR in diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: a meta-analysis of diagnostic performance. J Clin Microbiol 52:3731–3742. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01365-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mengoli C, Cruciani M, Barnes RA, Loeffler J, Donnelly JP. 2009. Use of PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suarez F, Lortholary O, Buland S, Rubio MT, Ghez D, Mahe V, Quesne G, Poiree S, Buzyn A, Varet B, Berche P, Bougnoux ME. 2008. Detection of circulating Aspergillus fumigatus DNA by real-time PCR assay of large serum volumes improves early diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in high-risk adult patients under hematologic surveillance. J Clin Microbiol 46:3772–3777. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01086-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Springer J, White PL, Hamilton S, Michel D, Barnes RA, Einsele H, Loffler J. 2016. Comparison of performance characteristics of Aspergillus PCR in testing a range of blood-based samples in accordance with international methodological recommendations. J Clin Microbiol 54:705–711. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02814-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White PL, Barnes RA, Springer J, Klingspor L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Morton CO, Lagrou K, Bretagne S, Melchers WJ, Mengoli C, Donnelly JP, Heinz WJ, Loeffler J, EAPCRI . 2015. Clinical performance of Aspergillus PCR for testing serum and plasma: a study by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. J Clin Microbiol 53:2832–2837. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00905-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White PL, Wingard JR, Bretagne S, Loffler J, Patterson TF, Slavin MA, Barnes RA, Pappas PG, Donnelly JP. 2015. Aspergillus polymerase chain reaction: systematic review of evidence for clinical use in comparison with antigen testing. Clin Infect Dis 61:1293–1303. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SCA, Sorrell TC, Meyer W. 2015. Aspergillus and Penicillium, p 2030–2056. In Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC, Funke G, Landry ML, Richter SS, Warnock DW (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 11th ed American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moser SA, Wicker J. 2016. Commercial methods for identification and susceptibility testing of fungi, p 214–272. In Truant AL. (ed), Manual of commercial methods in clinical microbiology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dannaoui E, Borel E, Monier MF, Piens MA, Picot S, Persat F. 2001. Acquired itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Antimicrob Chemother 47:333–340. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dannaoui E, Persat F, Monier MF, Borel E, Piens MA, Picot S. 1999. In-vitro susceptibility of Aspergillus spp. isolates to amphotericin B and itraconazole. J Antimicrob Chemother 44:553–555. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denning DW, Venkateswarlu K, Oakley KL, Anderson MJ, Manning NJ, Stevens DA, Warnock DW, Kelly SL. 1997. Itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1364–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chryssanthou E. 1997. In vitro susceptibility of respiratory isolates of Aspergillus species to itraconazole and amphotericin B. Acquired resistance to itraconazole. Scand J Infect Dis 29:509–512. doi: 10.3109/00365549709011864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bader O, Weig M, Reichard U, Lugert R, Kuhns M, Christner M, Held J, Peter S, Schumacher U, Buchheidt D, Tintelnot K, Gross U, MykoLabNet-D Partners . 2013. cyp51A-based mechanisms of Aspergillus fumigatus azole drug resistance present in clinical samples from Germany. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3513–3517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00167-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bueid A, Howard SJ, Moore CB, Richardson MD, Harrison E, Bowyer P, Denning DW. 2010. Azole antifungal resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: 2008 and 2009. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:2116–2118. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choukri F, Botterel F, Sitterle E, Bassinet L, Foulet F, Guillot J, Costa JM, Fauchet N, Dannaoui E. 2015. Prospective evaluation of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates in France. Med Mycol 53:593–596. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myv029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morio F, Aubin GG, Danner-Boucher I, Haloun A, Sacchetto E, Garcia-Hermoso D, Bretagne S, Miegeville M, Le Pape P. 2012. High prevalence of triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, especially mediated by TR/L98H, in a French cohort of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1870–1873. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snelders E, van der Lee HA, Kuijpers J, Rijs AJ, Varga J, Samson RA, Mellado E, Donders AR, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2008. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med 5:e219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Linden JW, Arendrup MC, Warris A, Lagrou K, Pelloux H, Hauser PM, Chryssanthou E, Mellado E, Kidd SE, Tortorano AM, Dannaoui E, Gaustad P, Baddley JW, Uekotter A, Lass-Florl C, Klimko N, Moore CB, Denning DW, Pasqualotto AC, Kibbler C, Arikan-Akdagli S, Andes D, Meletiadis J, Naumiuk L, Nucci M, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2015. Prospective multicenter international surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1041–1044. doi: 10.3201/eid2106.140717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhary A, Kathuria S, Randhawa HS, Gaur SN, Klaassen CH, Meis JF. 2012. Isolation of multiple-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in India. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:362–366. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockhart SR, Frade JP, Etienne KA, Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Balajee SA. 2011. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from the ARTEMIS global surveillance study is primarily due to the TR/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4465–4468. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00185-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seyedmousavi S, Hashemi SJ, Zibafar E, Zoll J, Hedayati MT, Mouton JW, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2013. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus, Iran. Emerg Infect Dis 19:832–834. doi: 10.3201/eid1905.130075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, Hirano K, Iwanaga N, Ide S, Mihara T, Hosogaya N, Takazono T, Morinaga Y, Nakamura S, Kurihara S, Imamura Y, Miyazaki T, Nishino T, Tsukamoto M, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, Yasuoka A, Tashiro T, Kohno S. 2012. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:584–587. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05394-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camps SM, van der Linden JW, Li Y, Kuijper EJ, van Dissel JT, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ. 2012. Rapid induction of multiple resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy: a case study and review of the literature. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:10–16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05088-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verweij PE, Snelders E, Kema GH, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2009. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a side-effect of environmental fungicide use? Lancet Infect Dis 9:789–795. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P, Lortholary O, Sylvester R, Rubin RH, Wingard JR, Stark P, Durand C, Caillot D, Thiel E, Chandrasekar PH, Hodges MR, Schlamm HT, Troke PF, de Pauw B. 2002. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 347:408–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Linden JW, Snelders E, Kampinga GA, Rijnders BJ, Mattsson E, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Kuijper EJ, Van Tiel FH, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2011. Clinical implications of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands, 2007–2009. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1846–1854. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2013. Risk assessment on the impact of environmental usage of triazoles on the development and spread of resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus species. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chong GL, van de Sande WW, Dingemans GJ, Gaajetaan GR, Vonk AG, Hayette MP, van Tegelen DW, Simons GF, Rijnders BJ. 2015. Validation of a new Aspergillus real-time PCR assay for direct detection of Aspergillus and azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Microbiol 53:868–874. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03216-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White PL, Posso RB, Barnes RA. 2015. Analytical and clinical evaluation of the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay for detection of invasive aspergillosis and resistance to azole antifungal drugs during testing of serum samples. J Clin Microbiol 53:2115–2121. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00667-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong GM, van der Beek MT, von dem Borne PA, Boelens J, Steel E, Kampinga GA, Span LF, Lagrou K, Maertens JA, Dingemans GJ, Gaajetaan GR, van Tegelen DW, Cornelissen JJ, Vonk AG, Rijnders BJ. 2016. PCR-based detection of Aspergillus fumigatus Cyp51A mutations on bronchoalveolar lavage: a multicentre validation of the AsperGenius assay in 201 patients with haematological disease suspected for invasive aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:3528–3535. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyon GM, Abdul-Ali D, Loeffler J, White PL, Wickes B, Herrera ML, Alexander BD, Baden LR, Clancy C, Denning D, Nguyen MH, Sugrue M, Wheat LJ, Wingard JR, Donnelly JP, Barnes R, Patterson TF, Caliendo AM, for the AsTeC, IAAM, EAPCRI Investigators . 2013. Development and evaluation of a calibrator material for nucleic acid-based assays for diagnosing aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 51:2403–2405. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00744-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Nguyen MH, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR, Young JA, Bennett JE. 2016. Executive summary: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 63:433–442. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu X, Zhang Z-L, Zheng S-Y. 2015. Highly sensitive DNA detection using cascade amplification strategy based on hybridization chain reaction and enzyme-induced metallization. Biosens Bioelectron 66:520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ademtech. 2013. Crime Prep Adem-Kit: instruction for manual protocol, v1.0. Ademtech SA, Pessac, France. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vermeulen E, Lagrou K, Verweij PE. 2013. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a growing public health concern. Curr Opin Infect Dis 26:493–500. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arendrup MC, Bille J, Dannaoui E, Ruhnke M, Heussel CP, Kibbler C. 2012. ECIL-3 classical diagnostic procedures for the diagnosis of invasive fungal diseases in patients with leukaemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 47:1030–1045. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Hoog GS, Guarro J, Gené J, Figueras MJ. 2014. Atlas of clinical fungi, 4th ed, online version Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Munoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.