Abstract

SLC1A3 encodes the glial glutamate transporter hEAAT1, which removes glutamate from the synaptic cleft via stoichiometrically coupled Na+-K+-H+-glutamate transport. In a young man with migraine with aura including hemiplegia, we identified a novel SLC1A3 mutation that predicts the substitution of a conserved threonine by proline at position 387 (T387P) in hEAAT1. To evaluate the functional effects of the novel variant, we expressed the wildtype or mutant hEAAT1 in mammalian cells and performed whole-cell patch clamp, fast substrate application, and biochemical analyses. T387P diminishes hEAAT1 glutamate uptake rates and reduces the number of hEAAT1 in the surface membrane. Whereas hEAAT1 anion currents display normal ligand and voltage dependence in cells internally dialyzed with Na+-based solution, no anion currents were observed with internal K+. Fast substrate application demonstrated that T387P abolishes K+-bound retranslocation. Our finding expands the phenotypic spectrum of genetic variation in SLC1A3 and highlights impaired K+ binding to hEAAT1 as a novel mechanism of glutamate transport dysfunction in human disease.

Introduction

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, and altered brain excitability caused by disturbed glutamate homeostasis plays a role in various paroxysmal neurological disorders1–3. Specifically, glutamate is a potent trigger of cortical spreading depression (CSD), the electrophysiological correlate of migraine aura4, and imbalance of glutamate release and clearance has been shown to underlie hemiplegic migraine (HM), a severe monogenic subtype of migraine with transient hemiparesis and other aura symptoms5,6.

EAAT1 is a glial glutamate transporter that contributes to glutamate clearance in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, diencephalon and caudal brainstem7. Genetic variation in SLC1A3 – the gene encoding EAAT1 - has been linked to several neurological disorders with partially overlapping clinical features8–11. In 2005, Jen et al. reported a SLC1A3 missense mutation in a child with a complex syndrome comprising episodic ataxia, prolonged hemiplegia with migraine and seizures8. Here, we searched for and identified a novel heterozygous SLC1A3 mutation in a young man with a similar but less severe clinical phenotype with recurrent episodes of migrainous headache accompanied by transient hemiparesis. To characterize the functional effects of the newly identified mutation on transporter function and compare them with results on other SLC1A3 mutations, we used both electrophysiology and biochemistry.

Results

Case history and genetic analysis

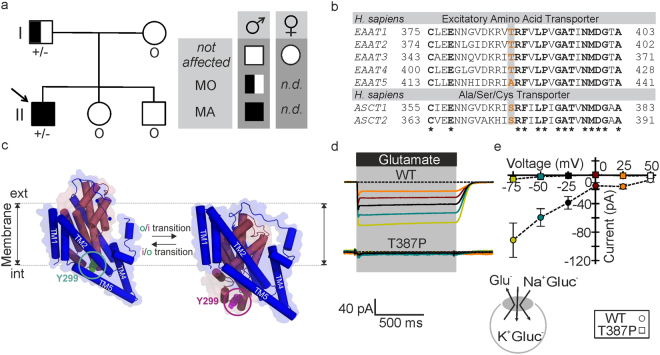

The patient is a now 22-year-old man from Serbia. Since age 11, he has suffered several episodes of severe migrainous headache with nausea and recurrent vomiting, accompanied by transient neurological deficits, including visual disturbances, prominent dysphasia and unilateral sensory and motor deficits; hemiparesis was reported to compromise his ability to hold/lift things. Headache was responsive to treatment with ibuprofen. Mild head trauma was reported as a triggering event in at least one attack. Retrospectively, the exact sequence and duration of neurological deficits could not be reliably determined. On three occasions, the patient presented to the hospital immediately after the onset of such attacks, and neurological evaluation at that time confirmed persistence of right-sided hemiparesis and dysphasia. Neuroimaging (both computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging), performed during three attacks, was normal, while CSF (C erebro s pinal f luid) analysis, performed during one attack, showed mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (9 cells/µl). EEG showed reversible left parieto-occipital slowing on one occasion, but was without evidence of seizure patterns. Interictal neurological examination was normal, and there was no evidence of episodic or permanent ataxia and no history of epileptic seizures. In subsequent years, the patient continued to experience similar attacks with severe headache with dizziness, mechanosensitivity, blurred vision, nausea and sometimes vomiting, but without associated neurological deficits. There was no evidence of headache attacks with focal neurological deficits in any other family member, but the patient’s father was found to suffer from migraine without aura (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

SLC1A3 mutation causes the exchange of the conserved threonine 387 by proline in hEAAT1. (a) Pedigree of the kindred with SLC1A3 T387P mutation. MA: migraine with aura (including hemiplegia); MO: migraine without aura. Arrow: index patient. Genotypes are indicated below each symbol (+/− denotes heterozygosity for SLC1A3 T387P variant; o DNA not available). (b) On the protein level, the variant causes a threonine (ACC) to proline (CCC) change at position 387. Multiple alignment of human excitatory amino acid transporters (hEAATs) and neutral amino acid transporters (ASCTs) shows that the T387 homologue positions in the transporter isoforms are preferentially occupied by hydroxylated amino acids. (c) Position of the T387- homologue residue Y299 in the EAAT topology model in the outward (o, green circle, modified from 2NWX.pdb) and inward (i, magenta circle, modified from 4P3J.pdb) conformation (dark purple: trimerization domain; dark red: transport domain). (d) Representative current traces from whole-cell patch clamp recordings from HEK293T cells expressing WT (top) and T387P (bottom) hEAAT1 under uptake conditions with permeant anions substituted by gluconate. Pipette solution (in mM): 115 K-gluc, 2 Mg-gluc, 5 EGTA, pH 7.4; Bath solution: 140 K-gluc, 1 Mg-gluc, 2 Ca-gluc, 5 TEA, pH 7.4, ± 5 L-Glutamate. Glutamate perfusion is indicated by a horizontal black bar. (e) Current-voltage relationship from glutamate transport for WT (circles) and mutant (squares, n = 5/5) hEAAT1. Holding potentials used in the transport experiments are color-coded.

The combination of migraine with unilateral motor deficits in at least some attacks phenotypically resembles hemiplegic migraine. In an initial screen of established HM genes (CACNA1A, ATP1A2 and SCN1A)12 as well as in PRRT2, which was recently implicated in HM and other paroxysmal phenotypes13, mutations in any of these genes were ruled out. Sequencing of SLC1A3 revealed a heterozygous nucleotide change c.1159 A > C (NM_004172). The variant was not detected in 100 control chromosomes nor listed in the databases dbSNP (Short Nucleotide Variations Database), ExAC (Exome Aggregation Consortium) and EVS (Exome Variant Server). Analysis of the parental DNA revealed the variant in the father, while DNA from other family members was not available (Fig. 1a). The variant c.1159 A > C predicts substitution of threonine 387 by proline (T387P). Thr387 is conserved in transmembrane helix 7 of mammalian EAAT1–4 transporters, but neither in EAAT5 nor in the related neutral amino acid exchangers (ASCTs) (Fig. 1b). EAAT glutamate transport is based on a large-scale rotational-translational movement of the substrate-harboring transport domain relative to the static trimerization domain14,15. Thr387 (Tyr299 in GltPh) is part of the transport domain and translates by 17 Å and rotates away from the trimerization domain during isomerization to the inward-facing conformation (Fig. 1c).

T387P impairs hEAAT1-mediated glutamate transport

To study possible disease-associated changes in glutamate transport we expressed WT and T387P hEAAT1 in mammalian cells. Glutamate transport is associated with net charge transfer and can therefore be quantified by measuring glutamate-elicited currents2. In cells intracellularly dialyzed with K+-based solution in the absence of permeant anions, WT hEAAT1 generated robust currents upon L-glutamate application using a piezo-driven perfusion system, whereas no glutamate-elicited currents were observed in cells expressing T387P hEAAT1 (Fig. 1d,e).

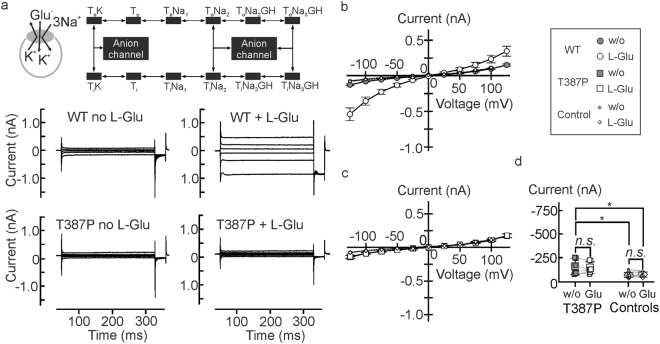

T387P abolishes hEAAT1-associated currents in the presence of internal K+

EAATs assume anion-conducting conformations from certain intermediate states of the transport cycle16,17, and EAAT anion currents therefore represent a simple initial test which steps in the transport cycle are affected by T387P. The presence of the more permeant NO3 − as the main anion increases current amplitudes and permits characterization of EAAT anion currents with negligible contributions of uptake currents18. Figure 2a shows representative whole-cell current responses to voltages between −125 mV and +125 mV from HEK293T cells internally dialyzed with a K+- based solution expressing WT or T387P hEAAT1. Application of 0.1 mM L-glutamate resulted in a fourfold increase of the WT hEAAT1 current amplitude at -125 mV (P U < 0.001, d Co = 0.82) (Figs 2a,b and 3e). T387P causes a profound reduction of hEAAT1 anion currents under these conditions and abolished their substrate dependence (P U = 0.59, d Co = 0.20, n = 9/11) (Fig. 2a,c,d and 3e). T387P hEAAT1 currents were slightly larger than background (P t = 0.024 (w/o L-glu)/0.013 (0.1 mM L-glu), Fig. 2c,d, see online supplementary text) indicating some residual activity under these conditions.

Figure 2.

Internal potassium abolishes hEAAT1 anion currents in T387P hEAAT1. (a) Representative whole-cell patch clamp recordings from HEK293T cells expressing WT (left) or T387P (right) hEAAT1 internally dialyzed with K+-based solutions in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of glutamate. Inset depicts the glutamate transport cycle16,17,19. (b and c) Current-voltage relationships for WT (b, circles), mutant (c, squares) hEAAT1, and untransfected HEK293T cells (b and c, small diamonds) under these experimental conditions (n = 9/12/8). (d) Statistical analysis of current amplitude differences from untransfected cells (small diamonds) and T387P hEAAT1 transfected HEK293T cells (squares) at a holding potential of −125 mV under uptake conditions. Bath solution (in mM): 140 NaNO3, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 5 TEA-Cl, pH 7.4; Pipette solution: 115 KNO3, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 5 L-glutamate, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4.

Figure 3.

T387P hEAAT1 anion currents in the presence of internal Na+. (a) Representative current traces from whole-cell patch clamp recordings from HEK293T cells expressing WT (left) or T387P (right) hEAAT1 internally dialyzed with Na+-based solutions in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of glutamate. Inset depicts the states within the glutamate transport cycle the transporter can assume during glutamate application in these experiments. (b and c) Current-voltage relationships for WT (b, circles) and mutant (c, squares) hEAAT1 under these experimental conditions (n = 9/9). Bath solution (in mM): 140 NaNO3, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.1 L-Glutamate, 5 HEPES, 5 TEA-Cl, pH 7.4; Pipette solution: 115 NaNO3, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 5 L-glutamate, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. (d) Sodium dependences of WT (circles) and T387P (squares) hEAAT1 anion currents were determined by external sequential perfusion with solutions, in which NaNO3 was equimolarly substituted with CholineNO3 in the presence of 5 mM L-glutamate. (e) Mean current amplitudes at −125 mV for WT (circles, black bars) and mutant (squares, grey bars, n = 4/5) hEAAT1 anion currents under several experimental conditions as indicated.

Glutamate is cotransported into the cell together with 3 Na+ and 1 H+, followed by the K+- bound re-translocation of the transporter back to the outward-facing state2. The two rate-limiting steps permit identification of two half-cycles, often denoted as Na+- and K+ hemicycles (Figs 2a and 3a). To separate T387P effects on these hemicycles we measured WT and mutant anion currents with Na+ as main internal cation19. Under these conditions, anion currents displayed a different time and voltage dependence than with internal K+, reflecting the tight coupling of anion channel gating to the transport cycle. With internal Na+, L-glutamate increased WT current amplitudes threefold (P U = 0.005, d Co = 0.64). T387P anion currents resemble WT currents in its time and voltage dependence, but are slightly smaller in amplitude. L-glutamate increased mean current amplitudes of the mutant significantly, but less efficiently than WT (P U = 0.006, d Co = 0.83) (Fig. 3a–c,e). Figure 3d shows the external sodium dependence of WT and mutant anion currents with internal Na+, demonstrating indistinguishable relative Na+ -dependences.

For WT as well as for T387P hEAAT1, we tested block of NO3 − currents by 100 µM DL-TBOA20 with both K+ int (P paired-t = 0.002/0.049, d Co = 0.92/0.22, n = 4/3, WT/T387P) or Na+ int (P paired-t = 0.005/0.015, d Co = 0.87/0.73, n = 5/4, WT/T387P) (Supplementary Fig. S1). In all cases, application of TBOA resulted in comparable background current amplitudes, indicating that our experimental procedure permits measurements of EAAT anion currents in isolation under all applied conditions.

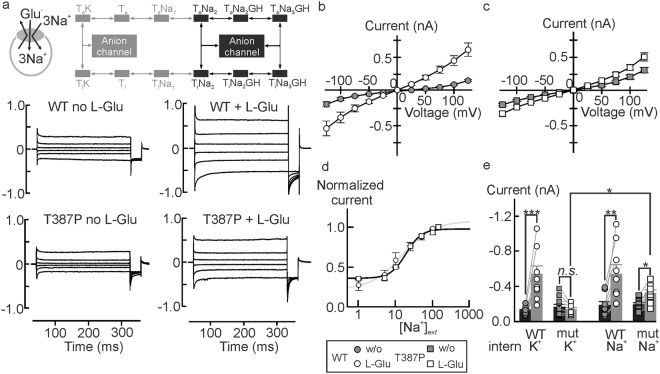

T387P impairs K+ association to the inward-facing transporter

To further delineate transport steps that might be modified by T387P we used fast substrate application using a piezo-driven solution exchange under different ionic conditions (Fig. 4)19,21–24. We initially performed such experiments with cells dialyzed with a Na+-containing solution supplemented with saturating [L-glutamate]. These conditions – the so-called exchange mode - abolish forward glutamate transport, but permit glutamate transporter translocation upon rapid changes in external [L-glutamate]. These conformational changes give rise to capacitive currents25,26 (Fig. 4a,c,f) that permit quantification of the translocation process. The time course of current relaxation depends on the speed and the probability of translocation, whereas the amplitude further depends on the number of transporters in the membrane26. A comparison of τ ON between transient currents of glutamate uptake and Na+-exchange conditions showed no differences (Glu: P t = 0.06; Na: P t = 0.093, n = 8/6; Figs 1d, 4a). WT and mutant currents differed in peak currents (P U < 0.001, d co = 0.58), and there are slight differences in their time dependence (P t = 0.005, d Co = 0.65, Fig. 4a,b). For fast application of L-glutamate we used a high concentration (5 mM) to permit rapid establishment of saturating [L-glutamate]. This maneuver significantly delays the complete substrate removal that is necessary because of the high substrate affinity of the transporters, preventing a meaningful analysis of current responses upon substrate-removal.

Figure 4.

Impaired potassium association prevents glutamate uptake by T387P hEAAT1. (a) Representative current responses of HEK293T cells dialyzed with a solution containing (in mM) 115 Na+-gluconate and 5 L-glutamate and expressing WT (left) or T387P (right) hEAAT1 to rapid application of glutamate (Na+-glutamate exchange conditions). (b) Mean ON and OFF peak amplitudes and mean relaxation time constants (τ ON, OFF) from experiments shown in a (n = 9/7). (c) Representative current responses to rapid application of K+ to cells dialyzed with a K+-gluconate-based internal solution (K+-exchange conditions). In all of these experiments permeant anions were equimolarly substituted with gluconate in intra- (in mM, 115 K/Na-gluc, 2 Mg-gluc, 5 EGTA, pH. 7.4, 0/5 L-glutamate) and extracellular solutions (140 K/Na-gluc, 1 Mg-gluc, 2 Ca-gluc, 5 TEA, pH 7.4, ± 0/5 L-glutamate). (d) Mean ON and OFF peak amplitudes and relaxation time constants (τ ON, OFF) for the experiments illustrated in c (n. a. ~ not analyzed; n. s. ~ not significant, n = 8/11). (e) State diagram for the glutamate uptake cycle with highlighted four-state potassium hemicycle and list of fitting results for simulated currents from WT (top) and T387P (bottom) hEAAT1. (f) Simulated currents (solid lines) are shown with their underlying template recordings (light grey). (g) Simulated residence probabilities WT (black bars, circles, solid lines) and mutant EAAT1 (grey bars, squares, dashed lines) calculated from the data given in (e).

To test transitions within the K+ hemicycle we used rapid application of K+ to cells internally dialyzed with K+-gluconate-based solutions. Under these conditions application of 140 mM K+ results in a capacitive current due to transport domain translocation26. For WT hEAAT1, the complete charge movement is recovered upon stepping back to K+- free solution, albeit with a slower time constant (Fig. 4c,d). This behavior reflects the strict requirement for EAAT transporter re-translocation in the K+-bound conformation. Without external K+, there is only translocation possible from the inward to the outward-facing conformation, so that relaxation takes longer than for conditions with external K+. The different time courses of the ON and OFF capacitive currents result in differing peak current amplitudes (P U = 0.001; d Co = 0.42, Fig. 4c,d). For T387P hEAAT1, the time dependence of the transient ON-current (upon K+ application) resemble WT results (P t = 0.94; Fig. 4d). However, mutant OFF time courses are faster than WT OFF time courses (P t = 0.002) and similar to mutant ON time courses (P paired-t = 0.42, Fig. 4d). This similarity is not caused by the limited time resolution of our solution exchange system, since amplitudes of ON and OFF- capacitive currents were similar for T387P, but different for WT transporters (Fig. 4c,d).

To quantify the T387P-induced changes in the K+ hemicycle we fitted capacitive currents under K+ transport conditions to the glutamate transport scheme using a genetic algorithm (Fig. 4e,f). Under these conditions transporters can only assume four different states, either in the apo conformation (Ti, To) or with bound potassium (TiK, ToK). For T387P hEAAT1 we obtained negligible K+ association rates to Ti and slightly altered translocation rates (Fig. 4e). We then inserted these rates into a published kinetic model to predict the steady-state probabilities that WT and mutant transporter resides in certain transport cycle states (Fig. 4g, and Supplementary Fig. S1). There are only small differences in steady-state residence probabilities under K+-transport conditions (Supplementary Fig. S2a), illustrating slow K+-association and -dissociation from Ti. This largely unaltered distribution explains the similarity in WT and mutant peak current amplitudes of K+ -induced capacitive currents under conditions (Fig. 4c,f). Figure 4g depicts residence probabilities under forward glutamate transport conditions. In the absence of external L-glutamate T387P hEAAT1 accumulates in Ti (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Slow Na+-bound inward translocation is still possible in mutant transporters, however, impaired K+-binding prevents re-translocation to To. Application of glutamate promotes inward translocation and results in the exclusive presence of mutant hEAAT1 in Ti. Thus, no L-glutamate association is possible for the mutant transporter, causing the absence of transport, anion currents and capacitive currents upon glutamate application in the mutant (Figs 1 and 2).

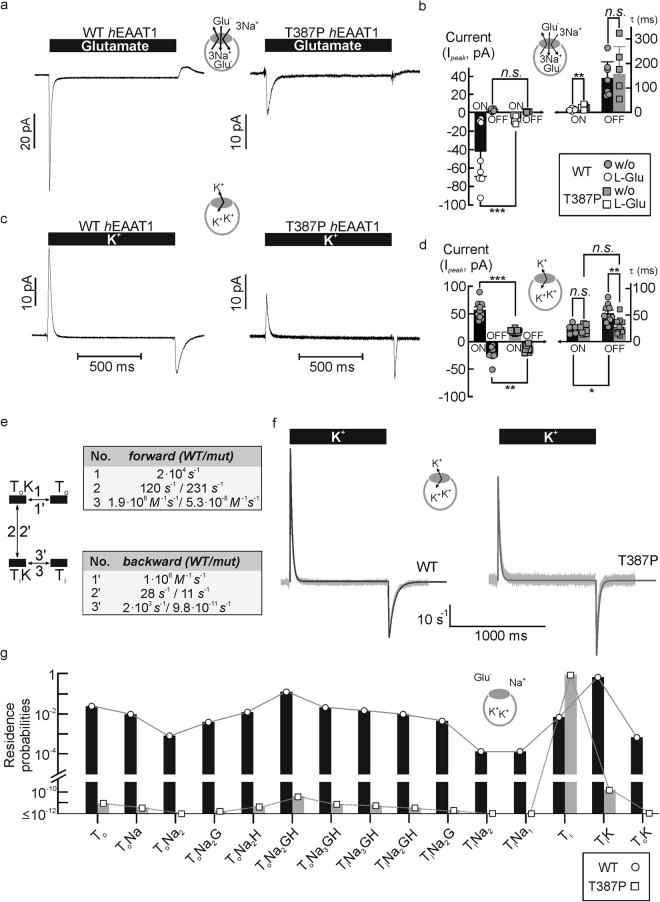

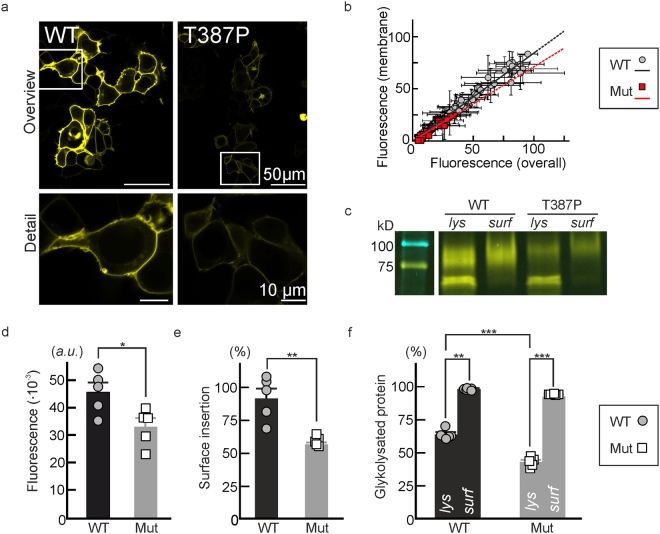

T387P impairs the number of hEAAT1 in the surface membrane

We next quantified the effects of T387P on protein expression levels and subcellular distribution (Fig. 5). Confocal images show almost exclusive insertion of WT hEAAT1-YFP into surface membrane or in domains in close proximity. Mutant fusion proteins also preferentially insert into the surface membrane, however, with reduced expression levels (Fig. 5a). Figure 5b shows plots of surface membrane fluorescence intensities versus whole cell fluorescences for cells expressing either WT (grey circles) or mutant (red squares) proteins. The slopes of such linear regressed data sets provide the surface insertion probability and demonstrate slightly reduced values for mutant hEAAT1.

Figure 5.

T387P decreases hEAAT1 transporter density in the surface membrane. (a) Representative confocal images from HEK293T cells expressing WT (left) or T387P (right) hEAAT1-YFP fusion proteins. (b) YFP-fluorescence distributions (grey values, a. u.) from WT (grey circles, black line, n = 72) and mutant (red squares, red line, n = 24) YFP-fusion proteins from HEK293T cells. Linear fits to the values point to slightly different surface insertion ratios for WT and mutant EAAT1 (slopesWT/T387P: 0.84/0.71; R 2 WT/T387P: 0.97/0.91) (c) Representative cropped region of a SDS-PAGE showing YFP-fluorescence from total lysate (lys) or surface biotinylated protein (surf) for WT and T387P hEAAT1-YFP. MWL = Molecular Weight Ladder, BioRad-Precision plus, Dual color, #1610374. The corresponding full-length gel is provided as Supplementary Fig. 3. (d) Pooled total YFP- fluorescence emissions from WT (circles) and T387P hEAAT1-YFP (squares, n = 5/5). (e) Statistical analysis of surface biotinylation from experiments as shown in c indicates a lower ratio for surface expression of expressed protein for the mutant (P t = 0.011, n = 5/5). (f) Surface insertion probability for core- and complex-glycosylated WT (black bars) and T387P (grey bars) protein.

We next employed surface biotinylation to quantify hEAAT1 trafficking with an alternative technique. SDS-PAGE analysis of whole cell lysates and biotinylated fractions (Fig. 5c) provide fluorescent fusion protein amounts in whole cells as well as in surface membranes. T387P reduces total protein expression to ~72% of WT level (P t = 0.024) (Fig. 5c,d). Figure 5e depicts mean ratios of surface membrane inserted protein by total protein. The surface membrane inserted mutant protein is decreased to ~50%. hEAAT1 predominantly exists in the core- or in complex-glycosylated state27 resulting in two major fluorescent bands in SDS PAGE (Fig. 5c). The percentage of complex-glycolysated protein in whole cell lysates was decreased for T387P hEAAT1 (P t < 0.001, d Co = 0.95). For WT as well as for mutant transporters complex-glycosylated protein inserted almost completely into the surface membrane (Fig. 5c,f).

Oligosaccharide side-chains are sequentially processed to the complex-glycosylated form in the Golgi apparatus, and analysis of hEAAT1 glycosylation thus indicate that T387P modifies early steps in hEAAT1 processing to its complex-glycosylated form. Since only complex-glycosylated transporters are inserted into the surface membrane (Fig. 5c,f), this processing defect not only explains lower protein expression levels (Fig. 5b,d), but also the discrete reduction in the number of mutant transporter in the plasma membrane (Fig. 5a,e).

Discussion

We here report a novel heterozygous SLC1A3 missense mutation in a patient with recurrent attacks of severe headache accompanied by transient focal neurological deficits including hemiparesis. Mutational screening of genes implicated in overlapping phenotypes, in particular HM, had been negative. The new variant was absent from 100 control chromosomes and public databases, the affected amino acid residue (T387) is highly conserved (Fig. 1), and functional analysis revealed a clear loss-of-function of mutant hEAAT1 (Figs 2–4).

In a patient carrying another SLC1A3 missense mutation8 migrainous headache was associated with a complex spectrum of neurological symptoms. Our patient manifests with hemiplegic migraine without ataxia or seizures, and the phenotype of his father (also a mutation carrier) has even less severe manifestations with migraine without aura. Although there were references in the medical records of a history of “migraine” in other relatives, no other family members except for the patient’s parents could be reached for evaluation. Moreover, only the DNA from parents was available for genetic analysis, preventing a meaningful co-segregation analysis. The father, who was also carrier of the T387P mutation, suffered from migraine without aura, possibly reflecting reduced penetrance, as has been reported in paroxysmal phenotypes such as HM28–30.

Detailed analysis of the functional consequences of the T387P mutation revealed loss-of-function of hEAAT1 function with physiological internal K+ (Figs 1 and 2), whereas WT and mutant transporters resembled each other functionally in cells with Na+-based internal solutions (Fig. 2). Analysis of capacitive currents elicited by changes in external K+ with K+ as only cationic substrate identified impaired K+ association as molecular basis of T387P hEAAT1 transporter dysfunction. Fitting rate constants of a glutamate transporter kinetic scheme to these currents revealed dramatically impaired K+ binding to the inward-facing transporter and faster K+-bound translocation. Such alterations will result in an accumulation of transporters in the inward-facing conformation and abolish transport and channel function in the presence of internal K+ (Fig. 4). Since the Na+ hemicycle is less affected, WT and mutant currents are similar in the absence of internal K+ (Fig. 3). Biochemical analysis demonstrated that T387P additionally impairs trafficking, but leaves the surface insertion probability mainly unaffected. This alteration decreases total expression levels and the number of mutant transporters in the surface membrane (Fig. 5), resulting in a further reduction of mutant currents under all tested conditions.

Thr387 might directly contribute to K+ binding, or the mutation might impair formation of binding sites necessary for K+ association from the cytoplasm. At present, the molecular basis of K+ binding to EAAT/GltPh is insufficiently understood. The current concept is that there is only one K+ binding site in the transport domain of the transporter26,31. K+ movement across the membrane is not based on conformational changes of the transport domain, but rather on a movement of the complete transport domain2. Our results are inconsistent with such a model. Whereas T387P has only minor effects on K+ binding to the outward-facing transporter, it causes a dramatic reduction of K+-association as well as -dissociation rate constants for the inward-facing hEAAT1 (Fig. 4). Our data would suggest the existence of multiple K+ binding sites within the transport domain and the consecutive occupation of these sites during translocation. Alternatively, T387P may modify closure of HP2 after K+ association and thus prevent K+-bound re-translocation. EAAT/GltPh translocation is only possible when the two hairpin loops (HP1 and HP2) are closed2. T387P-mediated changes in HP2 dynamics could also account for some minor alterations of mutant transporters that were observed under exchange conditions (Fig. 4,b).

Our clinical and functional data re-inforce the concept that disturbed glutamate homeostasis from genetic variations in SLC1A3 could lead to a broad spectrum of neurological manifestations with overlapping features. The first SLC1A3 mutation (P290R)8, arose de novo in a single patient with episodic ataxia, hemiplegia with migraine, and epilepsy, impairs glutamate transport and enhances hEAAT1 anion currents27,32, likely reducing glial intracellular [Cl−]33,34. Another SLC1A3 mutation, found in multiple members of a family with episodic ataxia (C186S), was reported to slightly reduce glutamate uptake levels9 and to modify intracellular transport of EAAT135, while hEAAT1 anion currents were not studied. A sequence variant predicting E219D, which was found in some individuals with Tourette syndrome10, increases the relative surface membrane insertion probability of hEAAT1, predicting gain-of-function of glutamate transport and anion channel activity. Gene duplication in SLC1A3 in patients with ADHD and/or autism-like features is also expected to increase hEAAT1 glutamate transport and anion currents11. In contrast to these published mutations, the SLC1A3 T387P mutation results in loss-of-function of glutamate transport and the loss of anion channel activity.

Glutamate is an important trigger of CSD, the correlate of migraine aura. Assuming that the episodes of transient hemiparesis and other neurological deficits in our patient are functionally related to aura events, impaired glutamate reuptake by functionally altered hEAAT1 is likely to increase susceptibility to these episodes. Accurate prediction of the extent of glutamate accumulation at the synapse caused by the mutation is currently not possible. Glial cells of the heterozygous patient are expected to express both WT and mutant transporter subunits, and the majority of trimeric hEAAT136,37 will contain WT as well as T387P hEAAT1 subunits. Individual subunits function independently of each other, and the localization of Pro387 does not predict altered interaction of mutant with WT subunits. Reduction of glutamate uptake in affected individuals will thus critically depend on the ratio of WT and mutant subunits in native cells, a parameter that we cannot determine at the moment. If WT and mutant subunits were expressed at identical levels, a reduction of hEAAT1-mediated glutamate uptake to about 50% would be expected. However, since T387P reduces the number of translated mutant hEAAT1 subunits (Fig. 5), this reduction might be even less pronounced. Taken together, our findings suggest that the mutation will only have a discrete effect on glutamate homeostasis in the affected patient. This illustrates how delicately glutamate concentrations have to be controlled in the human brain. Our result might explain the rather benign clinical course of the index patient as well as the phenomenon of reduced penetrance in his father.

In summary, our observation expands the phenotypic spectrum associated with genetic variation in SLC1A3, and our functional data on mutant hEAAT1 highlight distinct glutamate transporter dysfunctions in each of the reported paroxysmal neurological syndromes.

Methods

Patients and genetic analysis

In the index patient, direct sequencing was used to identify mutations in the already established genes associated to glutamate imbalance related paroxysmal disorders like episodic ataxia and hemiplegic migraine (CACNA1A, ATP1A2 and SCN1A) as well as PRRT2, which was recently implicated in HM and other paroxysmal phenotypes13. Subsequently, all exons and exon-intron boundaries of SLC1A3 were subjected to direct sequencing as previously described8. Targeted sequencing of the novel SLC1A3 variant was also performed in DNA samples from the parents and from 50 healthy control individuals. Novelty of the newly identified mutation was verified by database queries in dbSNP (Short Nucleotide Variations database; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp), ExAC (E xome A ggregation C onsortium) and EVS (E xome V ariant S erver). Written informed consent for genetic analysis was obtained from all participants in line with an approval from the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München (former affiliation of TF), and the index patient agreed with the publication of clinical and genetic details. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Functional characterization of WT and mutant EAATs

The T387P mutation and YFP-fusion of hEAAT1 proteins were generated and subcloned into the vector pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) using PCR-based strategies27,38. HEK293T cells were transfected using the Ca3(PO4)2 technique or as described previously18,27,38 and whole-cell patch clamped using EPC10 (HEKA Electronic, Germany) or Axopatch 200B (Molecular Devices, USA) amplifiers and standard solutions as described27,38. Current-voltage relationships were constructed from steady-state current amplitudes (I ss) 250 or 750 ms after the voltage jumps or concentration exposures (Figs 1,2 and 3). Possible contaminations with non-EAAT anion channels were tested by blocking WT and mutant hEAAT1 anion currents with the non-transportable blocker DL-TBOA (DL-threo-β-Benzyloxyaspartate, 100 µM, Tocris, Bio-Techne, Germany)20 (see supplementary Fig. S1). For fast application of substrates, a piezo-driven system with a dual-channel theta glass tubing was used (Fig. 4) (MXPZT-300, Siskiyou, USA) (see online supplementary text). Current amplitudes (Ipeak ON, OFF) were calculated from maximal peak currents of capacitive currents. Mean relaxation time constants (τON, OFF) of capacitive currents were calculated from pooled time constants of mono-exponential fits to the relaxation transients.

The K+-dependence of hEAAT1 currents was simulated by solving differential equations to a four-state scheme (Fig. 4e, see supplementary text) using published values as starting values19. Rate constants were estimated by optimizing the model against the time courses of currents using the genetic algorithm as implemented in the Python package DEAP39.

Confocal microscopy and biochemical characterization of EAAT fusion proteins

Confocal imaging was carried out on living cells as described (see supplementary text)40. Protein amounts were estimated by scanning SDS-PAGEs (10%) with a TyphoonTM FLA9500 gel scanner (GE Healthcare, Sweden) and quantifying YFP- fluorescence with the Fiji gel analysis package. Surface expression of hEAAT1 was quantified with cell surface biotinylation as described previously (see supplementary text)27.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with a combination of Clampfit (Molecular Devices, USA), Patchmaster (HEKA, Germany), SigmaPlot (Jandel Scientific, USA), MATLAB (Mathworks, USA), Fiji (Open Source), and Excel (Microsoft Corp., USA) programs. All data are given as means ± SEM, otherwise stated in the text. For statistic evaluation two-tailed Student’s-t-tests (t), paired-t-tests (paired-t) or Mann-Whitney-U-tests (U) were used (P < 0.05) and indicated as subscripted indices added to the P-values. Effect sizes were calculated from Cohen’s coefficients (d Co)41 and assessed as d Co < 0.2 (no), 0.2 ≤ d Co < 0.5 (weak), 0.5 ≤ d Co < 0.8 (medial) and 0.8 ≤ d Co < 1.3 (large)42.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the participation of the index family in this study. We would like to thank Dr. Susan Amara for providing an expression construct for hEAAT1, Drs. Claudia Alleva, Johnny Hendriks and Jan-Philipp Machtens for helpful discussions, and Arne Franzen and Petra Thelen for excellent technical assistance.

Author Contributions

P.K., Ch.F., and T.F. designed the research; P.K. and M.H. performed acquisition and analysis of data; T.F. and J.K. did patient recruitment, consenting, and genetic sequencing; D.K. carried out kinetic modeling and analyzed modeling results; J.C.J. discussed the paper; P.K., T.F., and Ch.F. drafted the figures and the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Christoph Fahlke and Tobias Freilinger contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-14176-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhou Y, Danbolt NC. GABA and glutamate transporters in brain. Front. Endocrinol. 2013;4:165. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandenberg RJ, Ryan RM. Mechanisms of glutamate transport. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:1621–1657. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen AA, Fahlke C, Bjorn-Yoshimoto WE, Bunch L. Excitatory amino acid transporters: recent insights into molecular mechanisms, novel modes of modulation and new therapeutic possibilities. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2015;20:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauritzen M. Pathophysiology of the migraine aura. The spreading depression theory. Brain. 1994;117(Pt 1):199–210. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moskowitz MA, Bolay H, Dalkara T. Deciphering migraine mechanisms: clues from familial hemiplegic migraine genotypes. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:276–280. doi: 10.1002/ana.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tottene A, et al. Enhanced excitatory transmission at cortical synapses as the basis for facilitated spreading depression in Ca(v)2.1 knockin migraine mice. Neuron. 2009;61:762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banner SJ, et al. The expression of the glutamate re-uptake transporter excitatory amino acid transporter 1 (EAAT1) in the normal human CNS and in motor neurone disease: an immunohistochemical study. Neurosci. 2002;109:27–44. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jen JC, Wan J, Palos TP, Howard BD, Baloh RW. Mutation in the glutamate transporter EAAT1 causes episodic ataxia, hemiplegia, and seizures. Neurol. 2005;65:529–534. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000172638.58172.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries B, et al. Episodic ataxia associated with EAAT1 mutation C186S affecting glutamate reuptake. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:97–101. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adamczyk A, et al. Genetic and functional studies of a missense variant in a glutamate transporter, SLC1A3, in Tourette syndrome. Psychiat. Genet. 2011;21:90–97. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328341a307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Amen-Hellebrekers CJ, et al. Duplications of SLC1A3: Associated with ADHD and autism. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2016;59:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrari MD, Klever RR, Terwindt GM, Ayata C, van den Maagdenberg AM. Migraine pathophysiology: lessons from mouse models and human genetics. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:65–80. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riant F, et al. PRRT2 mutations cause hemiplegic migraine. Neurol. 2012;79:2122–2124. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182752cb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes N, Ginter C, Boudker O. Transport mechanism of a bacterial homologue of glutamate transporters. Nature. 2009;462:880–885. doi: 10.1038/nature08616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crisman TJ, Qu S, Kanner BI, Forrest LR. Inward-facing conformation of glutamate transporters as revealed by their inverted-topology structural repeats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:20752–20757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908570106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machtens JP, et al. Mechanisms of anion conduction by coupled glutamate transporters. Cell. 2015;160:542–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fahlke C, Kortzak D, Machtens JP. Molecular physiology of EAAT anion channels. Pflugers Arch. 2016;468:491–502. doi: 10.1007/s00424-015-1768-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovermann P, Machtens JP, Ewers D, Fahlke CA. conserved aspartate determines pore properties of anion channels associated with excitatory amino acid transporter 4 (EAAT4) J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:23676–23686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergles DE, Tzingounis AV, Jahr CE. Comparison of coupled and uncoupled currents during glutamate uptake by GLT-1 transporters. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10153–10162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10153.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimamoto K, et al. DL-threo-beta-benzyloxyaspartate, a potent blocker of excitatory amino acid transporters. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:195–201. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franke C, Hatt H, Dudel J. Liquid filament switch for ultra-fast exchanges of solutions at excised patches of synaptic membrane of crayfish muscle. Neurosci. Lett. 1987;77:199–204. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90586-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otis TS, Kavanaugh MP. Isolation of current components and partial reaction cycles in the glial glutamate transporter EAAT2. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:2749–2757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02749.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasenhuetl PS, Freissmuth M, Sandtner W. Electrogenic binding of intracellular cations defines a kinetic decision point in the transport cycle of the human serotonin transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:25864–25876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.753319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burtscher, V., Hotka, M. & Sandtner, W. Substrate binding to serotonin transporters reduces membrane capacitance. Biophys. J. 112, 127a, 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.11.710.

- 25.Watzke N, Bamberg E, Grewer C. Early intermediates in the transport cycle of the neuronal excitatory amino acid carrier EAAC1. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;117:547–562. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.6.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grewer C, et al. Charge compensation mechanism of a Na+-coupled, secondary active glutamate transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:26921–26931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.364059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winter N, Kovermann P, Fahlke CA. point mutation associated with episodic ataxia 6 increases glutamate transporter anion currents. Brain. 2012;135:3416–3425. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riant F, et al. ATP1A2 mutations in 11 families with familial hemiplegic migraine. Hum. Mutat. 2005;26:281. doi: 10.1002/humu.9361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Vries B, et al. Systematic analysis of three FHM genes in 39 sporadic patients with hemiplegic migraine. Neurol. 2007;69:2170–2176. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000295670.01629.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomsen LL, et al. The genetic spectrum of a population-based sample of familial hemiplegic migraine. Brain. 2007;130:346–356. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verdon G, Oh S, Serio RN, Boudker O. Coupled ion binding and structural transitions along the transport cycle of glutamate transporters. eLife. 2014;3:e02283. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hotzy J, Schneider N, Kovermann P, Fahlke C. Mutating a conserved proline residue within the trimerization domain modifies Na+ binding to excitatory amino acid transporters and associated conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:36492–36501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.489385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parinejad N, Peco E, Ferreira T, Stacey SM, van Meyel DJ. Disruption of an EAAT-mediated chloride channel in a Drosophila model of ataxia. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:7640–7647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0197-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Untiet V, et al. Glutamate transporter-associated anion channels modulate intracellular chloride concentrations during glial maturation. Glia. 2017;65:388. doi: 10.1002/glia.23098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi MK, Yasui M. The transmembrane transporter domain of glutamate transporters is a process tip localizer. Scientific Rep. 2015;5:9032. doi: 10.1038/srep09032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gendreau S, et al. A trimeric quaternary structure is conserved in bacterial and human glutamate transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:39505–39512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nothmann D, et al. Hetero-oligomerization of neuronal glutamate transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:3935–3943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leinenweber A, Machtens JP, Begemann B, Fahlke C. Regulation of glial glutamate transporters by C-terminal domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:1927–1937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fortin FA, De Rainville F-M, Gardner M-A, Parizeau M, Gagne C. DEAP: Evolutionary algorithms made easy. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012;13:5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stolting G, Bungert-Plumke S, Franzen A, Fahlke C. Carboxy-terminal Truncations of ClC-Kb abolish channel activation by Barttin via modified common gating and trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:30406–30416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.675827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. (L. Erlbaum Associates, (1987).

- 42.Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size - or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012;4:279–282. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.