Abstract

Cryptochromes are evolutionarily conserved blue light receptors with many roles throughout plant growth and development. They undergo conformational changes in response to light enabling interaction with multiple downstream signaling partners. Recently, it has been shown that cryptochromes also synthesize reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to light, suggesting the possibility of an alternate signaling mechanism. Here we show by fluorescence imaging and microscopy that H202 and ROS accumulate in the plant nucleus after cryptochrome activation. They induce ROS-regulated transcripts including for genes implicated in pathogen defense, biotic and abiotic stress. Mutant cryptochrome alleles that are non-functional in photomorphogenesis retain the capacity to induce ROS-responsive phenotypes. We conclude that nuclear biosynthesis of ROS by cryptochromes represents a new signaling paradigm that complements currently known mechanisms. This may lead to novel applications using blue light induced oxidative bursts to prime crop plants against the deleterious effects of environmental stresses and toxins.

Introduction

Cryptochromes are blue light sensing receptors that regulate multiple processes of plant growth and development, including photomorphogenesis, de-etiolation, flowering initiation, stress response, and hormone signaling1–3. They are localized in the nucleus and function both directly and indirectly as core regulators of more than 20% of total cellular transcripts4–6. Structurally, cryptochromes are flavoproteins consisting of a conserved N-terminal light sensing domain (designated the PHR domain) and a less well-conserved C-terminal domain (designated CCE) of variable length that is important for nuclear localization and signaling7. Upon illumination, Arabidopsis cryptochromes interact with protein partners including phytochromes (PhyA and PhyB), the WD-repeat protein SPA1, the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1, and bHLH transcription factors CIB1,2, PIF3 and PIF48,9 which have a signaling role in photomorphogenesis or flowering initiation. Most of these partners attach to the PHR domain and release the CCE domain from the protein surface10,11. The ensuing suppression of COP1/SPA1-regulated degradation of transcription factors, such as HFR1 and HY5/HYH, results in photomorphogenesis and interaction with a large network of phytochrome, hormone, and stress signaling pathways12–15.

Recently, it has been reported that plant cryptochromes release reactive oxygen species (ROS) including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide (O2 •−) subsequent to illumination16,17. This follows from reoxidation of the bound flavin cofactor from the light activated radical (FADH°) or reduced (FADH-) redox state back to the oxidized (FADox) resting dark-adapted state18. ROS are damaging byproducts of metabolism originating in the chloroplasts, peroxisomes or mitochondria. They are also induced by several environmental stresses and function as core regulators of cellular processes including stress tolerance, root growth, senescence, hormonal responses, pathogen defense, defense mechanisms against ROS and induction of ROS scavenging pathways19–22.

Intriguingly, cryptochromes have been indirectly implicated in a variety of ROS signaling pathways including defensive responses to singlet oxygen, high light stress, and apoptosis23,24. There is furthermore considerable overlap in genes regulated by ROS and by cryptochromes in microarray studies24–27. Some of these effects result from indirect regulation by cryptochrome of cellular downstream intermediates that alter the levels of production of singlet oxygen in response to light within the plastid23, or through regulation of known signaling intermediates involved in photomorphogenesis26. However, the mechanism of such cross talk remains poorly understood24–27. Given that cryptochrome illumination leads to the stoichiometric biosynthesis of ROS in vitro, address the possibility that direct biosynthesis of ROS by cryptochromes may indeed play a signaling role in response to blue light exposure in living plants.

Results

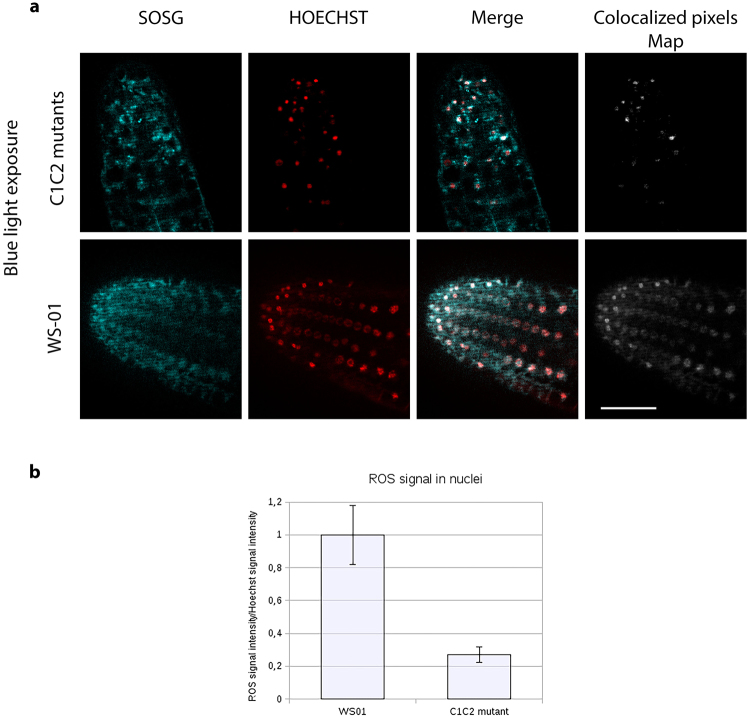

Prior studies have shown that an increase in levels of ROS (reactive oxygen species) can be observed within minutes of blue light illumination in the nuclei of Sf21 insect cell cultures expressing recombinant Arabidopsis cryptochromes16,17. However, these observations have not been linked to any physiological role in plants. We therefore first determined whether illumination would result in a detectable increase in levels of ROS in the nuclei of Arabidopsis plant seedlings. Cry – deficient mutant (cry1cry2) and cryptochrome overexpressing (Ws01) lines of the Wassilewskija (Ws) ecotype described previously28 were illuminated in the presence of the fluorescent probe Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green (SOSG) to detect singlet oxygen26, a byproduct of flavin reoxidation after illumination of cryptochromes (Fig. 1b)18. The apex of the primary root from 8 day old etiolated seedlings was assayed in order to avoid contribution of ROS from the chloroplasts (Fig. 2). After illumination, both cry-deficient (cry1cry2) and overexpressing (WsO1) Arabidopsis seedlings showed approximately similar levels of ROS, although levels were somewhat reduced in cry1cry2 mutants (Fig. 2, SOSG panel). However, when fluorescence staining resulting from SOSG was overlapped with Hoechst stain for localization of the nuclei (see Merge, Fig. 2), a clear distinction between mutant and cry overexpressing lines could be observed. Quantification of fluorescent signal (SOSG) from these images indeed showed that colocalized with the nucleus was higher by almost 80% in the Ws01 cryptochrome overexpressing cells as compared to cry-deficient cry1cry2 mutant seedlings (Fig. 2, Panel b). We conclude that increased ROS biosynthesis within the nuclear compartment occurs as a direct result of cryptochrome activation, consistent with a possible signaling role in the nucleus.

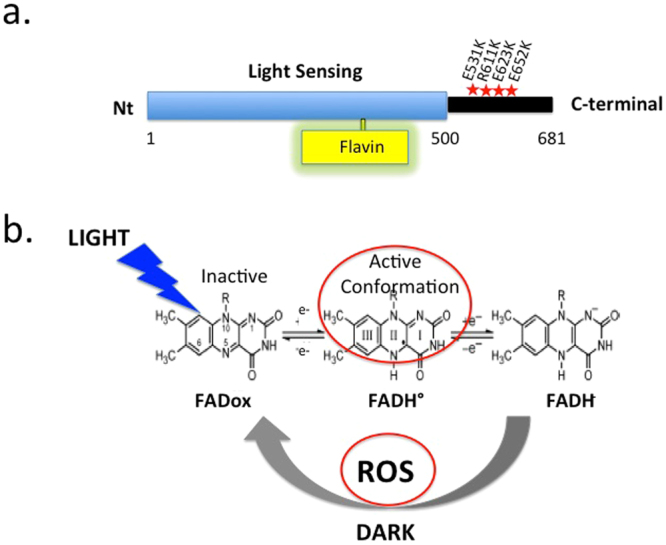

Figure 1.

Domain structure and photochemical reactions of Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1. Upper panel light sensing (flavin binding) domain and C-terminal domain are indicated showing position of point mutants used in this study. Lower panel: flavin photoreduction and reoxidation reactions which have been linked to biological signaling. Flavin (FAD) is oxidized in the dark-adapted state of the receptor and becomes reduced in the presence of light, forming the neutral radical (FADH°) flavin redox state which is correlated with protein conformational change linked to biological activation. Subsequent to flavin reduction, flavin reoxidation occurs in a light-independent reaction leading to the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Currently known paradigms for plant cryptochrome signaling are discussed in ref.1.

Figure 2.

Production and subcellular localization of ROS in Cryptochrome-1 overexpressing (WS01) and double mutant cry1cry2 (C1C2) seedlings exposed to blue light. Primary root tips from 8-day old etiolated Arabidopsis seedling (see methods) roots either lacking both cry1 and cry2 (C1C2 mutant) or over- expressing cryptochrome 1 (WS01) were treated with HOECHST for nuclear staining and SOSG for ROS staining for 30 minutes, exposed to blue light for 10 minutes, and then immediately viewed by a Zeiss AxioImager.Z1/ApoTome microscope. (a) Images show single z section that cross the nucleus. Colocalized pixels appear in white on the merged images and on the colocalized pixels maps. Scale bars are 25 μm. (b) using the segmentation and ROI manager tool on imageJ, fluorescence intensity of white and red pixels were quantified from these images for each nucleus and exported to LibreOffice calculator. The mean fluorescence intensity of >50 individual nuclei is shown.

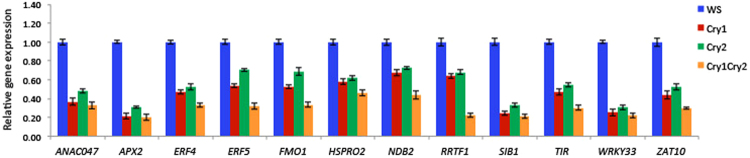

Numerous transcriptome analyses of both cryptochrome-regulated and ROS regulated gene expression are available in several plant species and involving many different stress and illumination protocols23–27; reviewed also in refs2,20. These indicate considerable overlap between light-regulated and ROS regulated gene expression. To verify the role of cryptochromes in a variety of ROS signaling pathways, we chose to analyse at random a number of genes reported to respond to ROS across several distinct functional categories implicated in economically important traits such as defense against pathogen attack, and other forms of biotic and abiotic stress. These include ROS induced ethylene responsive transcription factors (ERF4,5)29 and WRKY3327, the ROS regulated Zat zinc finger protein ZAT1030, Sigma Factor Binding Protein 1 (SIB1)29, Heat shock protein (HSPRO2)27, ROS detoxifying enzyme (APX2)30, oxidative stress responsive (ANACO47)31 and pathogen resistance gene FMO132. The expression of these genes was analysed in Arabidopsis wild type (Wt) and mutant (cry1, cry2, cry1cry2) seedlings after a short (3 hour) illumination with saturating blue light to induce the cryptochrome response33 (Fig. 3). All of these genes showed reduced expression in cryptochrome-deficient mutant seedlings after illumination with blue light. No changes in expression were observed in the dark (Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, expression is lower in either cry1 and cry2 single mutant seedlings as well, indicating that both proteins contribute towards a threshold of signal required for the transcriptional response.

Figure 3.

Effect of cryptochrome on transcription of representative ROS-regulated genes. Quantitative real-time PCR indicating the relative expression of twelve ROS-responsive genes investigated in WS (wild type), cry1, cry2, and cry1 cry2 mutant seedlings. All seedlings were null mutants (absence of protein) 28. Four-day-old dark-grown seedlings were transferred to blue light (60 μmol m−2 s−1) for 3 h. prior to RNA extraction and qPCR analysis. Three replicates (biological) were used to compute bar errors (representing the S.D.).

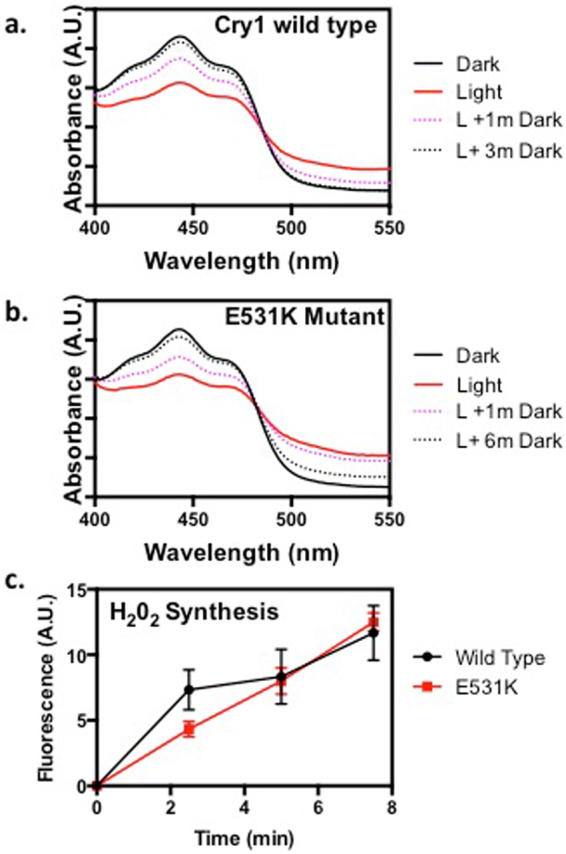

Cryptochromes have been shown to undergo structural change in response to light, which allow their interaction with a number of downstream signaling partners leading to biological function1,2. This light-induced conformational change is essential for photomorphogenesis2,12–15 and appears also to contribute to the role of cryptochrome in ROS signaling23–26. To resolve the question of whether direct biosynthesis of ROS by cryptochromes may by itself play a signaling role independently of conformational change, we analysed the biological activity of mutant alleles of CRY1 which had amino acid substitutions at their C-terminal (CCE) domain. Several such mutants had been previously described as inactive in hypocotyl growth inhibition and anthocyanin accumulation33–35, and as such can be concluded to be unable to undergo conformational change and partner protein interactions necessary for photomorphogenesis. To confirm that mutation of the C-terminal domain does not also affect light sensitivity or the formation of reactive oxygen (ROS) by the PHR domain of cryptochrome, we analysed protein from a mutant allele E531K34 which has a point mutation in the CCE domain outside of the region required for nuclear localization36. The recombinant E531K mutant protein was expressed and purified from a baculovirus expression system by established methods33, and compared to wild type AtCry1 for in vitro light sensitivity and flavin photoreduction. The mutant protein was comparable to the wild type AtCry1 both in the ability to undergo flavin photoreduction and the time course of reoxidation from the radical (FADH°) state back to the oxidized (FAD) inactive redox state (Fig. 4a,b). We further tested the ability of the mutant protein to synthesise H202 in response to light, which was observed to be comparable to wild type (Fig. 4c). These data indicate that mutation within the C-terminal domain does not significantly affect cryptochrome photochemistry or the ability to synthesise ROS, and that reported loss of function in photomorphogenesis34 is most likely due to inability to undergo light dependent conformational change.

Figure 4.

C-terminal point mutant of Arabidopsis cry1 retains light response and ROS biosynthetic capacity. Wild type (a) and E531K (b) mutant proteins were expressed and purified from baculovirus expression system as previously described33. ‘Dark’ shows spectra of isolated proteins prior to illumination. ‘Light’ indicates spectra after photoreduction for 30 seconds at 500 μmol m−2 s−1 blue light in the presence of 5 mM DTT . Samples were subsequently returned to dark and spectra taken at the indicated times (in min). (c). 100micromolar concentration of proteins were illuminated at 500 μmol m−2 s−1 blue light and aliquots taken at the indicated time for detection of ROS by AMPLEX RED fluorescence detection method as described16. Aliquots were taken at the indicated times. Error bars represent SD of three independent measurements.

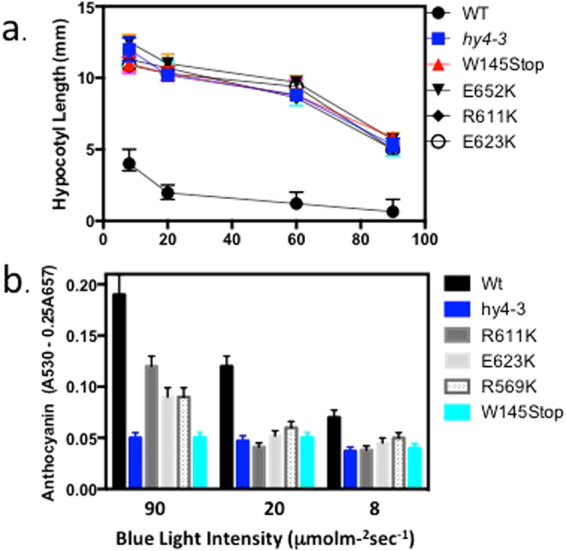

To determine whether these mutant alleles retain the ability to mediate ROS signaling, we analysed the effect of amino acid substitutions in the C-terminal domain of CRY1 on responsivity to stress and ROS regulated gene expression. We chose only C-terminal point mutant alleles of AtCry1 for analysis (R611K, E623K and E652K) which were located outside of any known functional region for signaling in vivo, including the nuclear localization region36 and residues of the C-terminal implicated in phosphorylation37. These alleles all showed levels of protein expression similar to wild type (Supplementary Fig. 2) For comparison purposes, a null mutant allele lacking detectable protein (W145 – STOP) was used as a control in addition to the cry1 reference allele (hy4-3), which also shows no detectable protein expression28. We first analysed these mutant alleles for hypocotyl growth inhibition at a range of blue light intensities (Fig. 5a, upper panel). All mutant alleles showed impairment in hypocotyl growth inhibition at blue light intensities ranging from 2 to 90 μmol m−2 s−1. These results indicate that all CRY C-terminal mutant alleles were biologically inactive for photomorphogenesis in spite of the fact that mutations in the C-terminal domain do not impede the capacity to synthesise ROS (Fig. 4). These results are consistent with a role for the C-terminal domain in inducing conformational change and interaction with signaling partners for these responses.

Figure 5.

Phenotypes of cryptochrome C-terminal point mutants. Wild type and mutant alleles were grown for seven days on petri plates at the indicated light fluence (upper panel) and hypocotyl length of seedlings was measured. Error bars represent SD of measurement from 10 seedlings. Anthocyanin accumulation was determined as described48, error represents SD of three independent measurements.

Anthocyanin accumulation is a highly regulated process occuring at the interface of numerous plant signaling pathways including photomorphogenesis. It is a consequence of both phytochromeand cryptochrome action. It is controlled by many of the same signaling intermediates that are implicated in other aspects of photomoprhogenesis such hypocotyl growth inhibition, such as HY5/HLH and COP138. However, anthocyanin accumulation also occurs more specifically in response to multiple forms of stress, and we therefore investigated whether C-terminal mutants of Cry1 which continue to synthesize ROS may also retain some capacity to regulate this response (Fig. 5b). Indeed, the levels of anthocyanin were substantially reduced in all cry1 mutant alleles in response to moderate intensities of blue light (at either 8 or 20 μmol m−2 s−1), consistent with previous reports34,35. However, at higher blue light intensity (90 μmol m−2 s−1), anthocyanin accumulation in the C-terminal mutant alleles R611K, E623K and E652K was significantly enhanced as compared to both of the null mutant alleles (Fig. 5b). These effects were not due to any overall partial activity (leakiness) of these C-terminal mutants, since there is no corresponding differential response in inhibition of hypocotyl elongation at any of these blue light intensities (Fig. 5a). These results indicate that cry1 mutants retaining the ability to synthesise ROS are also partially active in mediating anthocyanin accumulation under conditions of elevated stress (high light).

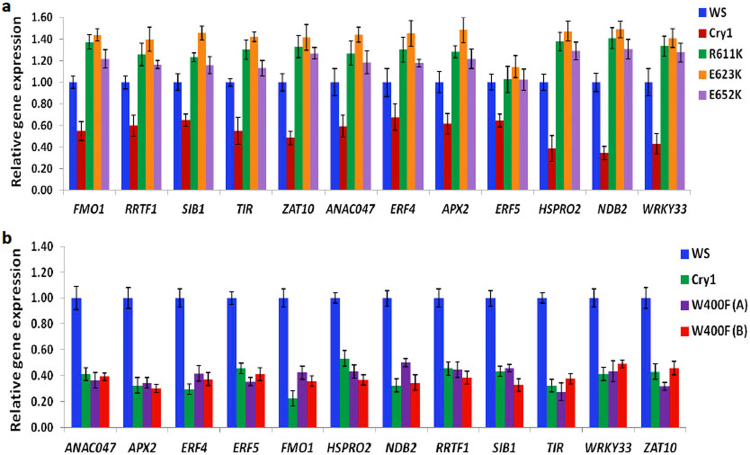

Finally, we analysed the C-terminal point mutant alleles for their ability to induce ROS regulated gene expression characterized in Fig. 3, as all of these mutants are flavin bound and synthesize ROS as isolated proteins in vitro (Fig. 4, see also Supplementary Fig. 3). As can be seen, all three C-terminal point mutant alleles R611K, E623K, and E652K induced the expression of ROS regulated genes in response to blue light (Fig. 6a). This was the case moreover for each of the twelve chosen target genes, which have been implicated in several distinct and independent ROS-regulated response pathways (see Fig. 3). Interestingly, levels of induced gene expression were in some cases even somewhat enhanced in these Cry mutant alleles as compared to wild type, although levels of Cry protein expression in all of the mutants was the same (Supplementary Fig. 2). This may have been due to mechanisms of homeostasis via conformational change in which the C-terminal mutants were deficient. Taken together with the results for anthocyanin accumulation (Fig. 5), these data show that C-terminal mutants of cryptochrome which have lost the ability to undergo conformational change nonetheless retain ROS signaling function.

Figure 6.

(a) C-terminal point mutants retain ability to induce ROS regulated gene expression. qPCR showing the relative expression of 12 ROS-responsive genes investigated in WS (wild type), Cry1 (null allele), and the indicated C-terminal point mutant seedlings. Four-day-old dark-grown seedlings were transferred to blue light (60 μmol m−2 s−1) for 3 h. prior to RNA extraction and qPCR analysis. Data are from three biological replicates n = 3; error bars indicate ± SD. No differences in expression were noted in dark grown seedlings without blue light treatment (supplementary Fig. 1). (b) Expression of ROS regulated genes in Trp triad W400F mutant Arabidopsis seedlings. qPCR shows expression of 12 ROS regulated genes in wild type (Ws), cry1 mutant, and expressing W400F Trp triad mutants (lines A and B - see Supplementary Fig. 3 for levels of mutant protein expression). No effect on gene expression is observed for the control cry mutant alleles. Data are from 3 biological replicates (n = 3), error bars indicate SD.

Discussion

In this work, we have addressed the important question of how cryptochromes interact with ROS signaling pathways in response to oxidative stress. We show that there is a visible accumulation of ROS in Arabidopsis seedlings as a result of cryptochrome activation by light (Fig. 2). This occurs also in the nucleus, and coincides with the rapid induction of ROS-regulated genes implicated in a number of different cellular response pathways (Fig. 3). Significantly, cryptochrome C-terminal mutant alleles that are impaired in normal light regulated conformational change and photomorphogenesis still retain the ability to synthesize ROS (Fig. 4 – See also Supplementary Fig. 3). These mutant alleles likewise retain partial activity in the regulation of stress response such as anthocyanin accumulation (Fig. 5). They furthermore retain an active signaling role in the induction of ROS-responsive genes (Fig. 6a). We note that seedlings expressing a mutation in the Trp triad residue W400F, which shows partial deficiency of flavin photoreduction in vivo 1, and thereby deficiency in biosynthesis of ROS, did not induce ROS responsive genes (Supplementary Fig. 2, Fig. 6b). Furthermore, seedlings overexpressing solely the N-terminal flavin binding domain of CRY1 reportedly induced many of the ROS responsive genes characterized in our study37. All of these data are therefore consistent with light dependent biosynthesis of ROS by cryptochrome as a possible signaling mechanism in the cases we have documented. Further transcriptome analysis will be required in order to clarify the number of cellular signaling pathways and the extent to which this mechanism may hold true.

The ROS signaling effects documented here in the C-terminal Cry1 mutant alleles appear to operate by distinct mechanisms than those described in previous reports of response to ROS in which cryptochromes have been implicated23,26. The previous studies show cryptochrome are implicated in ROS signaling pathways by indirect mechanisms involving regulation of singlet oxygen production by the chloroplast23 or by interaction with COP1 and transcription factors such as HY5/HYH which act downstream of cryptochromes in photomorphogenesis and plant growth. These processes require conformational change by cryptochromes which are lacking in C-terminal mutants of Cry1 (Fig. 4a). Therefore, blue-light induced signaling by C-terminal mutants likely involves direct synthesis of ROS and must function additively with, and act in a complementary manner, with the known signaling mechanism involving blue-light dependent conformational change.

Despite their capacity to synthesize ROS, cryptochromes would not be predicted to have a great impact on overall ROS biosynthesis in the cell; certainly nothing comparable to other sources of ROS such as in the plastid and mitochondria. This is because the cryptochrome photocycle is relatively slow, with a half-life of the reduced flavin state of several minutes38. Therefore, over several minutes, only a few molecules of ROS would be synthesized per cryptochrome even under saturating blue light conditions. Nonetheless, a unique feature of cryptochromes that is not present in other generators of ROS is their nuclear localization and potential proximity to redox sensitive signaling intermediates. This can greatly increase the effective concentration of ROS induced by blue light, as the most likely targets of ROS synthesised by cryptochromes may be transcription factors or other signaling intermediates to which they are in close proximity22.

One likely substrate, would be the family of G-Box binding transcription factors including GBF1 and MYC2, which are known to bind promoter elements related to high light stress signaling39. G-box binding factors are negative regulators of transcription whose binding affinity to DNA is shown to be greatly impaired by the presence of H202, resulting in their release from these promoters and subsequent induction of transcription40. G-box binding transcription factors are localized in close proximity to cryptochrome in the nucleus, as both are bound either directly or indirectly to the core regulator COP1 (E3 ubiquitin ligase)2,39. Since cryptochromes bind to COP1 independently of light, they would be in permanent close proximity to the G-box binding family of transcription factors, which bind to COP1 through the intermediary of HY5/HLH transcription factors39,40. Therefore, a pulse of blue light illumination would provide a localized burst of H202 sufficient to induce a transcriptional response from GBF-regulated promoters. Along these lines, biosynthesis of ROS by cryptochromes may contribute to its signaling role simply by increasing the local concentration of ROS near transcription factors to which cryptochromes have not been reported to bind directly, but which are assembled into the same complexes. Recent studies indicating a multiplicity of signaling molecules that are regulated directly by oxidation/reduction at cysteine residues greatly adds to the potential signaling substrates of cryptochromes41.

During photomorphogenesis, the predominant cryptochrome signaling mechanism is that involving conformational change and interaction with downstream signaling partners such as COP1 and SPA1. This is evident from the fact that mutants at the C-terminal domain completely abolish photomorphogenesis under normal plant growth conditions even though they can still synthesize ROS (see Fig. 4). This is consistent with the fact that, under steady state conditions, ROS levels are not primarily determined by environmental conditions (such as high light intensity) but rather by the interplay between the ROS producing and ROS-scavenging pathways, leading to a tightly regulate redox state equilibrium30. Given this process of redox homeostasis, induction of ROS through cryptochrome activation would not be expected to change intracellular levels of ROS under steady state, long-term growth conditions. Furthermore, under subsaturating light conditions, the efficacy of ROS formation as a signaling mechanism is doubtful as the quantum yield of the receptor is relatively low33, so that a mechanism of conformational change, wherein the activated form of cryptochrome is stable over a period of at least several minutes38 is the optimal signaling mechanism. As a result direct induction of ROS signaling pathways through cryptochrome is likely to occur primarily under short-term illumination at high light intensities, both to ensure saturating light intensities for cryptochrome-dependent ROS biosynthesis and to evade eventual cellular ROS scavenging and downregulation mechanisms. As a validation of this prediction, we observe that under the short term, high intensity illumination conditions used in this study we have observed robust cryptochrome-dependent induction of the ROS regulated FMO1 gene (involved in pathogen defense – Figs 3 and 6), whereas in prior studies carried out under continuous illumination in white light with this same gene there was no reported evidence for cryptochrome control32. Along these lines, transcriptome analyses of cryptochrome dependent gene expression under high light shows preponderance of stress regulated transcripts in Arabidopsis24, whereas different illumination conditions have not shown significant up-regulation of ROS responsive genes as a result of cryptochrome activation in Rhodobacter42 or in Brassica43, for example, although the converse appear to be true for tomato44.

From a practical perspective, almost all environmental stresses leading to economic loss such as extremes of temperature, salinity, drought, heavy metals, herbicides and pathogens involve formation of ROS, with concommittant induction of plant defense and protective mechanisms. The increase in ROS are generally transient and occur at the onset of the stress. Intriguingly, a number of studies have shown that pre-exposure to subthreshold levels of an “oxidative burst” can actively trigger a protective function or immunize plants against subsequent environmental stresses, a process known as acclamatory stress tolerance45–47. Cryptochromes are therefore ideal targets for such interventions. They can be completely photoreduced within less than a minute of illumination at light intensities which can be regulated to achieve desired levels of ROS directly within the nuclear compartment . Thus, a series of appropriately spaced blue light pulses can be delivered in the course of a night break which are sub-threshold in terms of inducing any form of oxidative damage or interrupting plant sleep/wake cycles, but sufficiently strong to induce desired plant defense mechanisms against selected environmental stress. Manipulation of cryptochrome responses may thereby become a new optogenetic tool to improve crop plant productivity at minimal cost and without chemical intervention.

Materials and Methods

Seedlings and plant growth conditions

All Arabidopsis seedlings were of ecotype WS. Cry1 (hy4-3) and cry2 mutant reference alleles28 lacked detectable protein. Other mutant alleles were either as previously described34,35 or screened and sequenced from genetic screens for blue light insensitive mutants as in ref.35. All seedling growth was on agar petri plates at 1/2xMS salts, 2%sucrose, pH 6.0, 0.8% agar. Seeds were sterilized as in ref.28, plated, retained at 4 °C for two days, then allowed to germinate for 24 hours in red light before being returned to darkness or the test light condition. Hypocotyl growth and anthocyanin content was measured as previously described35.

Imaging Experiments

10 plantlets (8–10 days old etiolated seedlings) were used per experiment and incubated in 2 ml of 200 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) comprising 2 µL HOECHST reagent (10 µM, Thermo Scientific), 2 µL DMSO (5 µM, Sigma -Aldrich) and 4 µL of SOSG (10 µM, Molecular Probes) for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Plantlets were then rinsed 4 times in potassium phosphate buffer (200 mM), then exposed either to dark or to saturating blue light (900 µm m−2 s−1) for 10 minutes and observed immediately with a Zeiss AxioImager.Z1/ApoTome microscope using a 20X objective, excitation/emission 350 nm/460–490 for HOECHST and 372/395–416 for SOSG reagent. Z- series were performed with a z-step of 1.5 µm. For quantification, the images were captured using a CCD-camera. Single z section were analysed for colocalization on ImageJ software (W. S. Rasband, ImageJ). Briefly, colocalized pixels were obtained by using colocalization color map plugging. Red structures on Hoechst images have been segmented to define each nucleus as a region of interest (ROI), then by using ROI manager tool, integrated density of cyan and red signal have been quantified for each ROI and exported to LibreOffice calculator.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana wild-type (WS), CRY1 null mutant, CRY2 mutant, CRY1-CRY2 double mutant and C-terminal mutants of Arg611Lys, Glu623Lys and Glu652Lys were grown and germinated as described above. Four-day-old dark-grown seedlings were transferred to blue light (60 μmol m−2 s−1) for 3 h or kept in dark. Seedlings were then collected and ground with liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Plant kit (Qiagen), and the first-strand cDNA synthesis was done using a Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using a SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All qRT-PCR reactions were amplified as follows: 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 57 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The expression levels were determined and normalized to the UBIQUITIN (UBQ1) expression using the comparative 2−∆∆Ct method. Primers of the 12 ROS genes used for gene expression analysis are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Protein Expression, extraction, and ROS detection

All methods were as previously described16. Briefly, the mutant allele E531K of cry1 was cloned into the pBakPak9 baculovirus expression vector (Clontech, inc.)including the presence of a 6 amino acid HIS tag at the N-terminus. The vector was transfected into Sf21 insect cell cultures and protein expression carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Recombinant protein was isolated over a nickel affinity column as described48. Concentration of protein used in the experiments was between 30–50 micromolar. Photoreduction experiments were peformed in a buffer of 50 mM NaPO4 pH 7.5, 5 mM DTT at18 °C. Subsequent to illumination, spectra were taken in a Cary Scan 300 UV/Vis spectrophotometer. For detection of ROS, samples of wild type Cry1 and E531K mutant proteins at the identical concentration were illuminated in a buffer of 50 mM NaPO4 pH 7.5 maintained on ice. Ilumination was at 1000 μmol m−2 s−1 in the absence of reducing agents. Aliqots were taken at the indicated times (Fig. 4) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. At the conclusion of the time course, samples were thawed and aliquots tested using the Amplex Red fluorescence detection system (Molecular Bioprobes) to determine the concentration of H202 as described16).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Adam Purvis, Derek Burdick and Dorothy Engle for assistance with protein experiments, and to Eloise Fort, Victoire Fort, Catherine Arieira, Colombine Frey, Pierre-Etienne Bouchet and Jacques Witczak for mutant screening and excellent technical support. Funding was from AFOSR (FA9550-14-0-0409) to M. Ahmad and C. Martino and NSF IRES 1658640 to J. Link.

Author Contributions

M.E.: performed experiments, designed experiments, wrote paper; L.D.A.: performed experiments, wrote paper; N.J.:performed experiments, A.D.: performed experiments, J.L.: performed experiments; C.F.M.: performed experiments, wrote paper; M.A.:performed experiments, designed experiments, wrote paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13832-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahmad M. Photocycle and signaling mechanisms of Arabidopsis cryptochromes. Current Opinions in Plant Biology. 2016;33:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu B, et al. Signaling mechanisms of plant cryptochromes in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Plant Res. 2016;129:137–148. doi: 10.1007/s10265-015-0782-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sancar A. Structure and function of DNA photolyase and cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptors. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2203–2237. doi: 10.1021/cr0204348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma L, et al. Light control of Arabidopsis development entails coordinated regulation of genome expression and cellular pathways. The Plant Cell. 2001;13:2589–2607. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.12.2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiao Y, Lau OS, Deng XW. Light-regulated transcriptional networks in higher plants. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8:217–230. doi: 10.1038/nrg2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phee BK, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of blue light signaling components in the Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1 mutant. Molecular Cell. 2007;23:154–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaves I, et al. The cryptochromes: blue light photoreceptors in plants and animals. Ann. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2011;62:335–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedmale UV, et al. Cryptochromes Interact Directly with PIFs to Control Plant Growth in Limiting Blue Light. Cell. 2016;164:233–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma D, et al. Cryptochrome 1 interacts with PIF4 to regulate high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation in response to blue light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:224–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511437113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondoh M, et al. Light-induced conformational changes in full-length Arabidopsis thaliana cryptochrome. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;413:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partch CL, et al. Role of structural plasticity in signal transduction by the cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptor. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3795–3805. doi: 10.1021/bi047545g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N, Deng XW. Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2000;405:462–466. doi: 10.1038/35013076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lian HL, et al. Blue-light-dependent interaction of cryptochrome 1 with SPA1 defines a dynamic signaling mechanism. Genes & Development. 2011;25:1023–1028. doi: 10.1101/gad.2025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duek PD, Elmer MV, van Oosten VR, Fankhauser C. The degradation of HFR1, a putative bHLH class transcription factor involved in light signaling, is regulated by phosphorylation and requires COP1. Current Biology. 2004;14:2296–2301. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu B, Zuo Z, Liu H, Liu X, Lin C. Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1 interacts with SPA1 to suppress COP1 activity in response to blue light. Genes & Development. 2011;25:1029–1034. doi: 10.1101/gad.2025011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Consentino L, et al. Blue-light dependent reactive oxygen species formation by Arabidopsis cryptochrome may define a novel evolutionarily conserved signaling mechanism. New Phytol. 2015;206:1450–62. doi: 10.1111/nph.13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jourdan N, et al. Blue-light dependent ROS formation by Arabidopsis Cryptochrome-2 may contribute towards its signaling role. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2015;10:e1042647. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1042647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller P, Ahmad M. Light activated cryptochrome reacts with molecular oxygen to form a flavin-superoxide radical pair consistent with magnetoreception. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:21033–21040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattacharjee, S. The Language of Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling in Plants Journal of Botany985298, 10.1155 (2012).

- 20.Dietz KJ, Mittler R, Noctor G. Recent Progress in Understanding the Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Cell Signaling. Plant Physiology. 2016;171:1535–1539. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia XJ, et al. Interplay between reactive oxygen species and hormones in the control of plant development and stress tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:2839–56. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandes N, Schmitt S, Jakob U. Thiol-Based Redox Switches in Eukaryotic Proteins. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 2009;11:997–1014. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danon A, Coll NS, Apel K. Cryptochrome-1-dependent execution of programmed cell death induced by singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17036–17041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608139103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleine T, Kindgren P, Benedict C, Hendrickson L, Strand Å. Genome-wide gene expression analysis reveals a critical role for CRYPTOCHROME1 in the response of Arabidopsis to high irradiance. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1391–1406. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.098293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts MR, Paul ND. Seduced by the dark side: integrating molecular and ecological perspectives on the influence of light on plant defence against pests and pathogens. New Phytologist. 2006;170:677–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen D, et al. Antagonistic basic helix-loop-helix/bZIP transcription factors form transcriptional modules that integrate light and reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1657–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiao Y, Ma L, Strickland E, Deng XW. Conservation and divergence of light-regulated genome expression patterns during seedling development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3239–56. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad M, et al. Action spectrum for cryptochrome-dependent hypocotyl growth inhibition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2002;129:774–785. doi: 10.1104/pp.010969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laloi C, et al. Cross-talk between singlet oxygen- and hydrogen peroxide-dependent signaling of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:672–677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609063103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller G, Shulaev V, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 2008;133:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehterov N, et al. Oxidative stress provokes distinct transcriptional responses in the stress-tolerant atr7 and stress-sensitive loh2 Arabidopsis thaliana mutants as revealed by multiparallel quantitative real-time PCR analysis of ROS marker and antioxidant genes. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2012;59:20e29. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griebel T, Zeier J. Light Regulation and Daytime Dependency of Inducible Plant Defenses in Arabidopsis: Phytochrome Signaling Controls Systemic Acquired Resistance Rather Than Local Defense. Plant Physiology. 2008;147:790–801. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.119503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Procopio M, et al. Kinetic modeling of the Arabidopsis cryptochrome photocycle: FADH° accumulation correlates with biological activity. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;28(7):888. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shalitin D, Yu X, Maymon M, Mockler T, Lin C. Blue Light–Dependent in Vivo and in Vitro Phosphorylation of Arabidopsis Cryptochrome 1. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2421–2429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad M, Lin C, Cashmore A. Mutations throughout an Arabidopsis blue-light photoreceptor impair blue-light-responsive anthocyanin accumulation and inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant Journal. 1995;8:653–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08050653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu X, et al. Derepression of the NC80 motif is critical for the photoactivation of Arabidopsis CRY2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7289–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701912104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He H, et al. The CNT1 Domain of Arabidopsis CRY1 Alone Is Sufficient to Mediate Blue Light Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:822–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbel V, et al. Lifetimes of Arabidopsis cryptochrome signaling states in vivo. Plant J. 2013;74:583–592. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gangappa SN, Srivastava AK, Maurya JP, Ram H, Chattopadhyay S. Z-Box Binding Transcription Factors (ZBFs): A New Class of Transcription Factors in Arabidopsis SeedlingDevelopment. Molecular Plant. 2013;6:1758–1768. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaikhali J, et al. Redox-mediated mechanisms regulate DNA binding activity of the G-group of basic region leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors in Arabidopsis. J.Biol.Chem. 2012;287:27510–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.361394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waszczak C, et al. Sulfenome mining in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:11545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411607111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fruhwirth S, Teich K, Klug G. Effects of the Cryptochrome CryB from Rhodobacter sphaeroides on Global Gene Expression in the Dark or Blue Light or in the Presence of Singlet Oxygen. PlOS1. 2012;7:e33791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma P, Chatterjee M, Burman N, Khurana JP. Plant Cryptochrome 1 regulates growth and development in Brassica through alteration in the expression of genes involved in light, phytohormone and stress signalling. Plant Cell and Environment. 2014;37:961–977. doi: 10.1111/pce.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez L, et al. Tomato plants overexpressing cryptochrome 2 reveal altered expression of energy and stress-related gene products in response to diurnal cues. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:994–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dat J, et al. Dual action of the active oxygen species during plant stress responses. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2000;57:779–795. doi: 10.1007/s000180050041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhattacharjee S. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative burst: roles in stress, senescence and signal transduction in plants. Current Science. 2005;89:1113–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Apel K, Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2004;55:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouly JP, et al. Cryptochrome blue light photoreceptors are activated through interconversion of flavin redox states. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:9383–9391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.