ABSTRACT

The in vitro activities of novel azoles compared to those of five antifungal drugs against clinical (n = 28) and environmental (n = 102) isolates of black mold and melanized yeast were determined. Luliconazole and lanoconazole had the lowest geometric mean MICs, followed by efinaconazole, against tested isolates compared to the other drugs. Therefore, it appears that these new imidazole and triazole drugs are promising candidates for the treatment of infections due to melanized fungi and their relatives.

KEYWORDS: melanized fungi, in vitro, MIC, efinaconazole, lanoconazole, luliconazole

TEXT

Black mold and melanized yeast, characterized by the presence of a pale-brown to dark melanin-like pigment in the cell wall, are a diverse group of filamentous, yeasts, yeast-like fungi and relatives which are commonly found on decomposing plant debris, dead plant material, rotten wood, air, and soil. Several genera belonging to the ascomycetous orders, i.e., Capnodiales, Chaetothyriales, Diaporthales, Dothideales, Pleosporales, Sordariales, and Venturiales, are characterized as black mold and melanized yeast and are relatively often encountered in human and animal disorders, ranging from mild cutaneous lesions to severe encephalitis in otherwise healthy individuals (1, 2). The importance of melanized fungi has recently gained increased focus, owing to the significant increase in the number of patients with predisposing risk factors throughout the world (1). Although dematiaceous fungi as agents of invasive infections are basically susceptible to most antifungal agents in vitro, treatment regimens are controversial and difficult, because frequent relapses and failures are observed when antifungal resistance is involved (3). Antifungal therapy or application of drug combinations is based on the experience from case series which mostly involved amphotericin B, itraconazole, terbinafine, and flucytosine as promising treatment options (1, 4). Although triazoles might be more effective based on the observation of low in vitro MIC values, excessive use of azole fungicides in the environment with long-term use of drugs in the prophylactic treatment of hospitalized patients has resulted in the development of drug resistance (5). Therefore, alternative antifungal agents with better activities and fewer side effects can help improve the management of these infections. Recently, the new azole agents luliconazole, lanoconazole, and efinaconazole were approved for the treatment of dermatophytosis and onychomycosis (6–9). The frequency of application and duration of treatment with these drugs are also favorable compared with those of other regimens used for the treatment of tinea pedis (6, 7). Previous studies have also shown potent activities of these antifungal agents against Candida albicans, Dermatophyte species, Malassezia species, and azole-resistant and azole-susceptible Aspergillus fumigatus strains, but resistance to these drugs has not been described so far (7–12). To the best of our knowledge, only limited data are available on the in vitro activities of these novel azoles against dematiaceous fungi and their relatives (13). Therefore, we aimed to investigate the in vitro activities of luliconazole, lanoconazole, efinaconazole, and five comparators against a large collection of dematiaceous fungi and their relatives from different clinical and environmental sources.

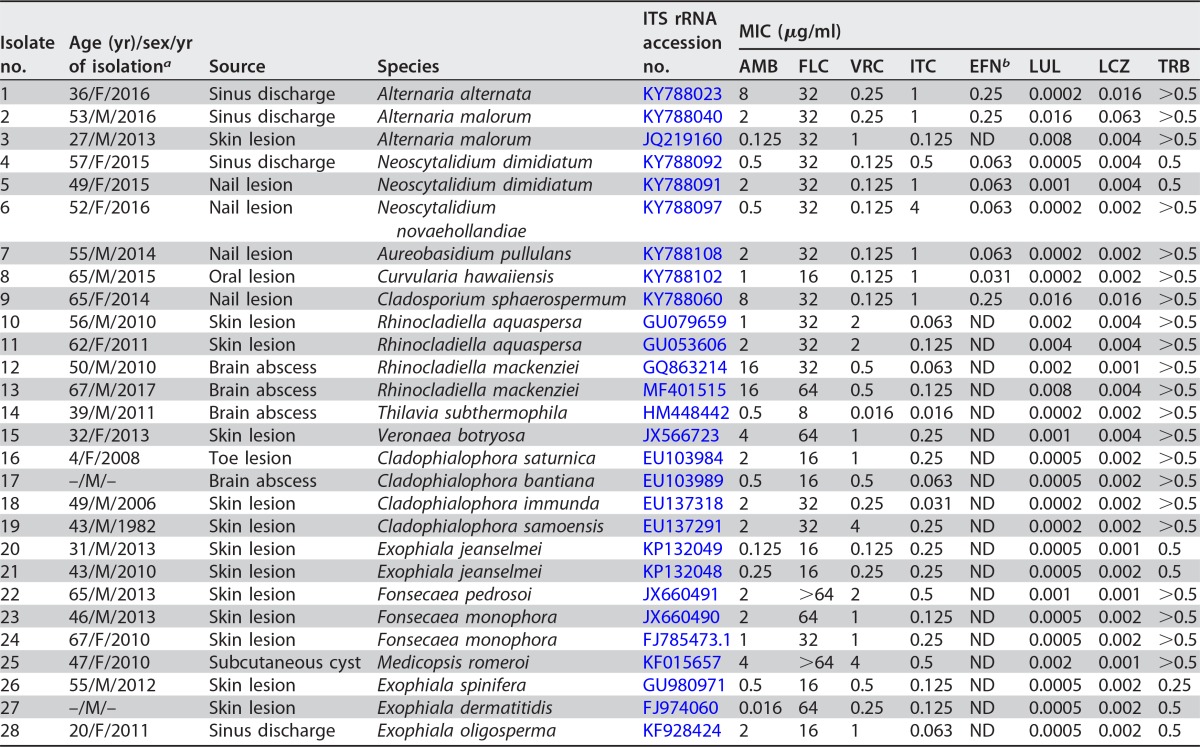

A total of 130 well-characterized dematiaceous isolates were obtained from the reference culture collections of the Invasive Fungi Research Center (IFRC), Sari, Iran. The clinical collections (n = 28) were recovered from a variety of specimens (Tables 1 and 2) comprising sinus discharge (n = 4), skin lesions (n = 13), cerebral abscesses (n = 4), nail lesions (n = 5), subcutaneous cyst (n = 1), and an oral lesion (n = 1). In addition, environmental isolates (n = 102) were collected from air (n = 39), soil (n = 33), wood, plant, and organic debris (n = 30) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Isolates were identified to the species level by DNA sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer 1-5.8 ribosomal DNA-ITS2 (ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2) rDNA region, as previously described (14). In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing was performed according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) document M38-A2 (15). Concentration ranges of 0.016 to 16 μg/ml for amphotericin B (AMB; Bristol-Myers-Squib, Woerden, The Netherlands), itraconazole (ITC; Janssen Research Foundation, Beerse, Belgium), and voriconazole (VRC; Pfizer, Central Research, Sandwich, United Kingdom); 0.063 to 64 μg/ml for fluconazole (FLU; Pfizer), 0.00005 to 0.031 μg/ml for luliconazole (LUL; Nihon Nohyaku Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan), 0.0002 to 0.125 μg/ml for lanoconazole (LCZ; Nihon Nohyaku Co. Ltd.), 0.001 to 0.5 μg/ml for efinaconazole (EFN; Nihon Nohyaku Co. Ltd.), and terbinafine (TRB; Novartis Research Institute, Vienna, Austria) were used. Conidial suspensions were prepared from up-to-week-old cultures on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco) by gently scraping the surfaces of the colonies with a sterile cotton swab wetted with sterile saline containing Tween 40 (0.05%). The supernatants containing mostly nongerminated conidia were adjusted spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 530 nm to an optical density (OD) that ranged from 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml, the supernatants were diluted 1:50 (except for Alternaria species, which were diluted 1:25) in RPMI 1640 medium, and the final inoculum in assay wells was between 2 × 104 and 5 × 104 CFU/ml, as determined by the use of quantitative colony counts to determine the viable numbers of CFU per milliliter (15). Plates were incubated at 35°C for 48 h (30°C only for Alternaria species) (16, 17). The MIC endpoints were defined with the aid of a reading mirror as the lowest concentration of drug that prevents any recognizable growth (100% inhibition) for all tested drugs, whereas a prominent reduction in growth (>50%) compared to the growth of the drug-free control was used for fluconazole (15). Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) and Paecilomyces variotii (ATCC 3630) were included as quality controls. All tests were performed in duplicate, and the differences of the mean values were evaluated statistically using Student's t test with the statistical SPSS package (version 7.0). P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

TABLE 1.

In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of 28 clinical melanized fungal isolates against eight antifungal agents

aF, female; M, male. Dashes represent unavailable data.

bND, not determined.

TABLE 2.

MIC data for all clinical isolates

| MIC data (μg/ml) | Results by antifungal drug |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB | FLC | VRC | ITC | EFN | LUL | LCZ | TRB | |

| Range | 0.016 to 16 | 8 to >64 | 0.016 to 4 | 0.016 to 4 | 0.031 to 0.25 | 0.0002 to 0.016 | 0.001 to 0.063 | 0.25 to >0.5 |

| Geometric mean | 1.2506 | 28.006 | 0.4313 | 0.2383 | 0.0966 | 0.0008 | 0.0028 | 0.4528 |

| MIC50 | 2 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.25 | ND | 0.0005 | 0.002 | >0.5 |

| MIC90 | 8 | 64 | 2 | 1 | ND | 0.008 | 0.008 | >0.5 |

Based on molecular characterization, Tables 1 and 3 and Table S1 in the supplemental material show the species distribution of black mold and dematiaceous yeast isolates according to their origins.

TABLE 3.

In vitro susceptibilities of 102 environmental melanized fungal isolates against eight antifungal agents

| Antifungal drug by strain typea | MIC range (μg/ml) | MIC50/MIC90 (μg/ml)b | Geometric mean (μg/ml) | No. of isolates susceptible by MIC (μg/ml)c |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00005 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | ||||

| All strains (n = 102) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 0.5 to 8 | 2/8 | 2.2 | 5 | 7 | 72 | 4 | 14 | ||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 to 64 | 32/64 | 38.4 | 14 | 47 | 41 | ||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.063 to 1 | 0.25/1 | 0.20 | 6 | 45 | 33 | 3 | 15 | ||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.25 to 4 | 1/4 | 1.18 | 1 | 6 | 75 | 7 | 13 | ||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.016 to 0.5 | 0.063/0.25 | 0.10 | 2 | 7 | 48 | 38 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0001 to 0.031 | 0.002/0.031 | 0.002 | 2 | 11 | 24 | 13 | 8 | 14 | 1 | 18 | 11 | ||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.0002 to 0.063 | 0.016/0.063 | 0.009 | 2 | 11 | 23 | 13 | 40 | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| TRB | 0.5 to >0.5 | >0.5/>0.5 | >0.5 | 102 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternaria alternata (n = 14) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 to 8 | 2/2 | 2.20 | 13 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 32 to 64 | 32/64 | 39.008 | 10 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.06 to 1 | 0.12/1 | 0.21 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 to 1 | 1/1 | 1 | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.06 to 0.5 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.15 | 5 | 8 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0002 to 0.03 | 0.0005/0.03 | 0.0019 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.002 to 0.06 | 0.015/0.06 | 0.014 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| TRB | 0.5 to >0.5 | >0.5/>0.5 | >0.5 | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternaria tenuissima (n = 10) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 to 2 | 2/2 | 2 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 32 to 64 | 32/64 | 45.2 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.06 to 1 | 0.25/1 | 0.24 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 to 4 | 1/1 | 1.14 | 9 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.06 to 0.5 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.17 | 3 | 6 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0002 to 0.03 | 0.015/0.03 | 0.0057 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.008 to 0.06 | 0.015/0.06 | 0.021 | 1 | 6 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other Alternaria species (n = 6)d | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 1 to 8 | ND | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 32 to 64 | ND | 40.31 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.25 to 1 | ND | 0.39 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.25 to 4 | ND | 0.79 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.06 to 0.25 | ND | 0.15 | 2 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0005 to 0.015 | ND | 0.0021 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.004 to 0.06 | ND | 0.013 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | ND | >0.5 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladosporium cladosporioides (n = 12) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 to 8 | 2/8 | 2.5 | 10 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 to 64 | 32/64 | 42.7 | 1 | 5 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.06 to 0.5 | 0.12/0.25 | 0.15 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5 to 2 | 1/1 | 0.94 | 2 | 9 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.03 to 0.25 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.076 | 2 | 7 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0001 to 0.015 | 0.001/0.015 | 0.0012 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.0002 to 0.015 | 0.004/0.015 | 0.0034 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladosporium sphaerospermum (n = 10) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 to 8 | 2/8 | 3.2 | 6 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 32 to 64 | 32/64 | 39.39 | 7 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.12 to 1 | 0.12/0.25 | 0.18 | 6 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 to 4 | 1/2 | 1.41 | 6 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.06 to 0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.18 | 2 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0005 to 0.015 | 0.002/0.015 | 0.0024 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.0002 to 0.015 | 0.004/0.015 | 0.0053 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ulocladium tuberculatum (n = 19) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 1 to 8 | 2/8 | 2.6 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 to 64 | 64/64 | 57.3 | 1 | 1 | 17 | ||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 to 1 | 0.25/1 | 0.38 | 2 | 10 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 to 4 | 1/4 | 1.8 | 10 | 1 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.06 to 0.5 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.17 | 7 | 7 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0002 to 0.031 | 0.004/0.031 | 0.003 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.002 to 0.063 | 0.016/0.063 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Bipolaris species (n = 8)e | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 0.5 to 2 | ND | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 to 32 | ND | 22.6 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.063 to 0.25 | ND | 0.11 | 2 | 5 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5 to 1 | ND | 0.9 | 1 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.016 to 0.25 | ND | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0002 to 0.016 | ND | 0.003 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.002 to 0.063 | ND | 0.011 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | ND | >0.5 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Neoscytalidium dimidiatum (n = 6) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 0.5 to 2 | ND | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 32 to 64 | ND | 35.9 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 to 0.25 | ND | 0.13 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5 to 4 | ND | 1.1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.063 | ND | 0.06 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0002 to 0.004 | ND | 0.0007 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.002 to 0.016 | ND | 0.004 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | 0.5 to >0.5 | ND | >0.5 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Phoma glomerata (n = 5) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 to 8 | ND | 3.03 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 to 64 | ND | 27.8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.063 to 0.25 | ND | 0.12 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 to 2 | ND | 1.3 | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.033 to 0.25 | ND | 0.06 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.001 to 0.004 | ND | 0.002 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.002 to 0.016 | ND | 0.005 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| TRB | 0.5 | ND | 0.5 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Drechslera dematioidea (n = 4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 to 4 | ND | 2.3 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 to 32 | ND | 19.2 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 to 0.25 | ND | 0.14 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 | ND | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.063 to 0.25 | ND | 0.12 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0005 to 0.004 | ND | 0.001 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.004 to 0.016 | ND | 0.007 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | ND | >0.5 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Aureobasidium pullulans (n = 3) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 | ND | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 32 to 64 | ND | 40.3 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 to 0.25 | ND | 0.15 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 | ND | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.063 | ND | 0.06 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0002 to 0.001 | ND | 0.0004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.002 to 0.016 | ND | 0.004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | ND | >0.5 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ochroconis constricta (n = 2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 to 8 | ND | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 32 to 64 | ND | 45.2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 to 1 | ND | 0.34 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 to 4 | ND | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.031 to 0.063 | ND | 0.04 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0005 to 0.002 | ND | 0.001 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.004 | ND | 0.004 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | 0.5 to >0.5 | ND | >0.5 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Didymella rabiei (n = 1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 8 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.12 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.016 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0002 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.002 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Exophiala phaeomuriformis (n = 1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.063 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.0005 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.004 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | 0.5 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Embellisia astragali (n = 1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AmB | 2 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FLU | 16 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.25 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| EFN | 0.06 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LUL | 0.002 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LCZ | 0.016 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| TRB | >0.5 | ND | ND | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

AmB, amphotericin B; FLU, fluconazole; VRC, voriconazole; ITC, itraconazole; EFN, efinaconazole; LUL, luliconazole; LCZ, lanoconazole; TRB, terbinafine.

MIC50, concentration at which 50% of the isolates were inhibited; MIC90, concentration at which 90% of the isolates were inhibited; ND, not determined.

Numbers in bold are modal values.

Includes A. malorum, n = 2; A. chlamydospora, n = 2; A rosae, n = 1; and A. japonica, n = 1.

Includes B. spicifera, n = 4; and B. hawaiiensis, n = 4.

Tables 1 to 3 summarize the MIC range, geometric mean (GM) MIC, MIC mode, MIC50, and when appropriate, the MIC90 of the tested antifungal drugs. All clinical and environmental strains had low MICs for luliconazole and lanoconazole, followed by efinaconazole, in comparison with other drugs, whereas the less active drugs were fluconazole and amphotericin B. Indeed, the widest ranges and the highest MICs were seen for fluconazole (8 to >64 μg/ml and 16 to 64 μg/ml) and amphotericin B (0.016 to 16 μg/ml and 0.5 to 8 μg/ml) against both clinical and environmental strains, respectively. The GM MICs against all clinical black fungal strains of various genera were as follows, in increasing order: luliconazole, 0.0008 μg/ml; lanoconazole, 0.0028 μg/ml; efinaconazole, 0.0966 μg/ml; itraconazole, 0.2383 μg/ml; voriconazole, 0.4313 μg/ml; terbinafine, 0.4528 μg/ml; amphotericin B, 1.25 μg/ml; and fluconazole, 28.006 μg/ml. The GM MICs of all environmental isolates were as follows: luliconazole, 0.002 μg/ml; lanoconazole, 0.009 μg/ml; efinaconazole, 0.10 μg/ml; voriconazole, 0.20 μg/ml; itraconazole, 1.18 μg/ml; amphotericin B, 2.2 μg/ml; terbinafine, >0.5 μg/ml; and fluconazole, 38.4 μg/ml. Generally, the GM MIC values of luliconazole and lanoconazole against all clinical and environmental isolates of melanized fungi were >6-log2 and >4-log2-dilution steps lower than those of efinaconazole and other azoles, respectively. However, no statistically significant (P > 0.05) differences in the lanoconazole, luliconazole, and efinaconazole susceptibility patterns were detected between strains. While species-based analysis of the MIC values is required, we provided overall MIC50, MIC90, and MIC ranges for the clinical isolates, since the number of strains per each genus/species is low. These data may still appear to be useful for clinical guidance due to difficulties and frequent absence of availability of species identification of dematiaceous fungi in routine practice.

The term “phaeohyphomycoses” is used to describe a heterogeneous group of cutaneous, subcutaneous, cyst, and disseminated fungal infections in which black mold and dematiaceous yeast are noted in samples through histopathology (3); however, chromoblastomycosis is a chronic progressive disorder histologically characterized by a granulomatous lesion with muriform cells caused by black yeast-like fungi and their relatives (1). Due to the increasing number of antifungal agents, there has been a great interest to evaluate the activities of these new imidazole and triazole drugs against different fungal pathogens and compare them to the reference antifungal agents (6–12). Despite the increasing number of studies on the efficacy of the newer agents for several pathogenic fungi, the in vitro antifungal susceptibility profiles against black fungi remain to be investigated. In addition, no comprehensive data on in vitro antifungal susceptibility profiles of black fungi have yet been published (13). Lanoconazole, luliconazole, and efinaconazole were found to interfere with ergosterol biosynthesis by inhibiting sterol 14-alpha demethylase and blocking fungal membrane ergosterol biosynthesis (6, 7). Based on the results in the present study, luliconazole, lanoconazole, and efinaconazole were the most active drugs against all tested isolates. Previous studies have shown that these novel imidazoles had low MICs against azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and dermatophyte species (10, 12). Furthermore, the great potency of luliconazole against Trichophyton species has been shown by Koga et al. (18, 19). Uchida et al. also showed that the GM MICs of luliconazole for Malassezia furfur, Malassezia sympodialis, and Malassezia slooffiae were approximately 1.4 μg/ml, 0.1 μg/ml, and 1 μg/ml, respectively (12). In addition, the current investigation showed potent activities of luliconazole, lanoconazole, and efinaconazole against clinical and environmental black mold and dematiaceous yeast isolates. Although data on the in vitro activity of efinaconazole against black fungi are limited, in previous studies by Tatsumi et al., the MICs of efinaconazole against Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, the causative agents of dermatophytosis, were in the ranges of 0.015 to 0.5 μg/ml and 0.06 to 0.5 μg/ml, respectively (20, 21). The MIC range of efinaconazole against T. rubrum was similar to that detected in the present study on black fungi. Moreover, efinaconazole was active against a variety of pathogenic fungi associated with onychomycosis (9). Of all the antifungal agents tested, fluconazole was the drug with the highest MIC values against black fungi, which is in line with the results from previous studies (16, 17, 22, 23). In conclusion, given the fact that fungal infection due to dematiaceous fungi has increased and treatment is still challenging, the selection of proper antifungal agents is therefore critical for appropriate therapy and in order to improve the management of infected patients. Therefore, it appears that these two new imidazoles and new triazoles are promising candidates for the treatment of phaeohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis caused by black mold and dematiaceous yeast.

Accession number(s).

The nucleotide sequences for the determined environmental isolates have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers KY788018 to KY788122 and MF422635 to MF422636 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (grant no. 94-01-27-28538) and Teikyo University of Medical Mycology, Tokyo, Japan, which we gratefully acknowledge. The work of Hamid Badali was financially supported by School of Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

We declare no potential conflicts of interest.

We alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chowdhary A, Perfect J, de Hoog GS. 2014. Black molds and melanized yeasts pathogenic to humans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10:a019570. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong EH, Revankar SG. 2016. Dematiaceous molds. Infect Dis Clin North Am 30:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revankar SG, Sutton DA. 2010. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 23:884–928. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt ME, Warnock DW. 2003. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and therapy of infections caused by dematiaceous fungi. J Chemother 15:36–47. doi: 10.1179/joc.2003.15.Supplement-2.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhary A, Kathuria S, Xu J, Meis JF. 2013. Emergence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains due to agricultural azole use creates an increasing threat to human health. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003633. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna D, Bharti S. 2014. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid 9:113–124. doi: 10.2147/CE.S49629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niwano Y, Ohmi T, Seo A, Kodama H, Koga H, Sakai A. 2003. Lanoconazole and its related optically active compound NND-502: novel antifungal imidazoles with a ketene dithioacetal structure. Curr Med Chem Anti-Infect Agents 2:147–160. doi: 10.2174/1568012033483097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niwano Y, Seo A, Kanai K, Hamaguchi H, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. 1994. Therapeutic efficacy of lanoconazole, a new imidazole antimycotic agent, for experimental cutaneous candidiasis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 38:2204–2206. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.9.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta AK, Simpson FC. 2014. Efinaconazole (Jublia) for the treatment of onychomycosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 12:743–752. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.919852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baghi N, Shokohi T, Badali H, Makimura K, Rezaei-Matehkolaei A, Abdollahi M, Didehdar M, Haghani I, Abastabar M. 2016. In vitro activity of new azoles luliconazole and lanoconazole compared with ten other antifungal drugs against clinical dermatophyte isolates. Med Mycol 54:757–763. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abastabar M, Rahimi N, Meis JF, Aslani N, Khodavaisy S, Nabili M, Rezaei-Matehkolaei A, Makimura K, Badali H. 2016. Potent activities of novel imidazoles lanoconazole and luliconazole against a collection of azole-resistant and -susceptible Aspergillus fumigatus strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:6916–6919. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01193-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchida K, Nishiyama Y, Tanaka T, Yamaguchi H. 2003. In vitro activity of novel imidazole antifungal agent NND-502 against Malassezia species. Int J Antimicrob Agents 21:234–238. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00362-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchida K, Nishiyama Y, Yamaguchi H. 2004. In vitro antifungal activity of luliconazole (NND-502), a novel imidazole antifungal agent. J Infect Chemother 10:216–219. doi: 10.1007/s10156-004-0327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh A, Singh PK, Kumar A, Chander J, Khanna G, Roy P, Meis JF, Chowdhary A. 2017. Molecular and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry-based characterization of clinically significant melanized fungi in India. J Clin Microbiol 55:1090–1103. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02413-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi; approved standard. CLSI document M38-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badali H, De Hoog GS, Curfs-Breuker I, Andersen B, Meis JF. 2009. In vitro activities of eight antifungal drugs against 70 clinical and environmental isolates of Alternaria species. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:1295–1297. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badali H, De Hoog GS, Curfs-Breuker I, Meis JF. 2010. In vitro activities of antifungal drugs against Rhinocladiella mackenziei, an agent of fatal brain infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:175–177. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koga H, Nanjoh Y, Makimura K, Tsuboi R. 2009. In vitro antifungal activities of luliconazole, a new topical imidazole. Med Mycol 47:640–647. doi: 10.1080/13693780802541518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koga H, Tsuji Y, Inoue K, Kanai K, Majima T, Kasai T, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. 2006. In vitro antifungal activity of luliconazole against clinical isolates from patients with dermatomycoses. J Infect Chemother 12:163–165. doi: 10.1007/s10156-006-0440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatsumi Y, Nagashima M, Shibanushi T, Iwata A, Kangawa Y, Inui F, Siu WJ, Pillai R, Nishiyama Y. 2013. Mechanism of action of efinaconazole, a novel triazole antifungal agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2405–2409. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02063-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatsumi Y, Yokoo M, Arika T, Yamaguchi H. 2001. In vitro antifungal activity of KP-103, a novel triazole derivative, and its therapeutic efficacy against experimental plantar tinea pedis and cutaneous candidiasis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1493–1499. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1493-1499.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng S, de Hoog GS, Badali H, Yang L, Najafzadeh MJ, Pan B, Curfs-Breuker I, Meis JF, Liao W. 2013. In vitro antifungal susceptibility of Cladophialophora carrionii, an agent of human chromoblastomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1974–1977. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02114-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badali H, de Hoog GS, Sudhadham M, Meis JF. 2011. Microdilution in vitro antifungal susceptibility of Exophiala dermatitidis, a systemic opportunist. Med Mycol 49:819–824. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.583285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]