ABSTRACT

Pentavalent antimonial has been the first choice treatment for visceral leishmaniasis; however, it has several side effects that leads to low adherence to treatment. Liposome-encapsulated meglumine antimoniate (MA) arises as an important strategy for chemotherapy enhancement. We evaluated the immunopathological changes using the mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with MA. The mice were infected with Leishmania infantum and a single-dose treatment regimen. Comparison was made with groups treated with saline, empty liposomes, free MA, and a liposomal formulation of MA (Lipo MA). Histopathological analyses demonstrated that animals treated with Lipo MA showed a significant decrease in the inflammatory process and the absence of granulomas. The in vitro stimulation of splenocytes showed a significant increase of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) produced by CD8+ T cells and a decrease in interleukin-10 (IL-10) produced by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the Lipo MA. Furthermore, the Lipo MA group showed an increase in the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets. According to the parasite load evaluation using quantitative PCR, the Lipo MA group showed no L. infantum DNA in the spleen (0.0%) and 41.4% in the liver. In addition, we detected a low positive correlation between parasitism and histopathology findings (inflammatory process and granuloma formation). Thus, our results confirmed that Lipo MA is a promising antileishmanial formulation able to reduce the inflammatory response and induce a type 1 immune response, accompanied by a significant reduction of the parasite burden into hepatic and splenic compartments in treated animals.

KEYWORDS: Leishmania infantum, chemotherapy, liposomes, meglumine antimoniate, visceral leishmaniasis

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis, one of the most important neglected diseases, is caused by Leishmania protozoans and is transmitted by the borne-vector sandfly females. This disease harms the lives of thousands of people around of the world. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is caused by Leishmania infantum and Leishmania donovani and is the most severe and fatal clinical form of the disease if untreated. Recent estimates report about 0.2 to 0.4 million cases of VL per year, with more than 90% occurring in six countries: India, Bangladesh, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Brazil (1).

Currently, leishmaniasis chemotherapy has few available drugs (pentavalent antimonials, amphotericin B deoxycholate, liposomal amphotericin B, miltefosine, and paromomycin), and most have toxic effects and different efficacies depending on the region of the globe (2). In Brazil, pentavalent antimonial (meglumine antimoniate [MA]) has been used for decades as the first choice for the treatment of VL (3). However, conventional chemotherapy with antimony is accompanied by a series of events that may decrease adherence to treatment. Reactions such as local pain by intramuscular administration and systemic effects, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness and myalgia, abdominal colic, and skin rashes, were observed. In more severe cases, these reactions may lead to cardiotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, pancreatitis, and hepatotoxicity (4). Because of these potential adverse reactions, the World Health Organization recommends and supports research into new drugs against leishmaniasis (5).

In this context, strategies such as modification of the drug delivery using liposomes and the use of artificial phospholipid vesicles have proven to be useful in stabilizing drugs and enhancing their pharmacological properties (6). Although there are several products on the market being used with considerable clinical success (for example, AmBisome and Doxil), there is currently no liposomal formulation of MA available (7).

One of the major challenges in liposomal formulations is to increase the time the drug stays in the circulation, preventing it from being rapidly removed by cells from the phagocytic mononuclear system (PMS) (8). As an alternative, the inclusion of covalently bound phospholipids to flexible hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), in the liposome composition has minimized this problem. The presence of PEG reduces the uptake of liposomes by the PMS and increases its permanence in the blood circulation. The polymer occupies the space adjacent to the surface of the liposome creating a steric hindrance and, consequently, impairs the interaction of macromolecules and cells with the liposome (9).

A recent study by Azevedo et al. (10), using a mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with MA, evaluated the pharmacokinetics of the formulation in dogs and demonstrated a prolonged antimony circulation time, as well as its targeting to the bone marrow. In addition, the reduction of the load using the liposome mixture was superior to the conventional or pegylated formulations administered separately in mice. In view of the promising results previously found, we sought here to evaluate the main immunopathological changes promoted by the treatment using the mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with MA.

RESULTS

Kinetics of L. infantum (strain MCAN/BR/2008/OP46) infection in BALB/c mice show circulation of the parasite first in the liver and then in the spleen.

Before starting the therapeutic scheme, we first determine what time is best for the administration of the treatment according to the dynamics of the L. infantum strain (MCAN/BR/2008/OP46) in target organs (liver and spleen) using the BALB/c mice model. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) revealed the presence of the DNA parasite in the liver at week 2 postinfection (Table 1). On the other hand, no positive animals were observed in the splenic compartment until week 5 postinfection. From week 6 postinfection, positive animals were observed in the spleen; however, the percentage of DNA detection of the parasite was reduced (only 40% of infected animals) with a low parasite burden in the tissue. In contrast, the liver showed 100% for the positive animals until week 4 postinfection, and the percentage of DNA detection of the parasite remained above 60% of the animals until the last week of evaluation (week 8). From week 7 postinfection, an increase in the sizes and friabilities of the livers in some animals were observed. Despite the reduction in the number of animals with a detectable parasite burden after week 7 postinfection, the parasite load in the liver remained high until the end of the evaluation period (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Percentage of L. infantum-infected mice presenting parasite DNA evaluated by qPCR in the spleen and liver

| Wk postinfection | Positivity ratea (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Spleen | Liver | |

| 2 | 0/5 (0) | 5/5 (100) |

| 3 | 0/5 (0) | 5/5 (100) |

| 4 | 0/5 (0) | 5/5 (100) |

| 5 | 0/5 (0) | 3/5 (60) |

| 6 | 1/5 (20) | 4/5 (80) |

| 7 | 2/5 (40) | 3/5 (60) |

| 8 | 1/5 (20) | 4/5 (80) |

That is, the number of positive mice/total number of mice tested.

Characterization of conventional and pegylated liposomal formulations.

The encapsulation efficiencies of meglumine antimoniate (MA) and the size distribution of the vesicles in conventional and pegylated formulations are presented in Table 2. Conventional liposomes composed of distearoylphosphatidylcholine/cholesterol/dicetylphosphate (DSPC/CHOL/DCP) showed a drug encapsulation efficiency of 20.5%. Pegylated liposomes composed of DSPC/CHOL/DCP/DSPE-PEG (distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine-polyethylene glycol 2000) showed a significantly higher encapsulation efficiency (30.6%) of MA. The mean hydrodynamic diameters of conventional liposomes and pegylated liposomes, as well as the mixed formulation, were ca. 200 nm and did differ significantly between the formulations. The polydispersity index showed that the suspensions of conventional and pegylated liposomes and their mixture were monodisperse (polydispersity index < 0.3). Pegylated liposomes showed reduced zeta potential (−6 mV) compared to conventional vesicles (−26 mV), a difference that can be attributed to the PEG surface layer. Interestingly, the mixed formulation showed intermediate value of zeta potential (−11 mV).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the liposomal suspensions containing meglumine antimoniate in relation to drug encapsulation efficiency, vesicle size distribution, and zeta potentiala

| Liposomal suspension | Encapsulation (%) | Vesicle size distributionb |

Zeta potential (mV) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (nm) | Polydispersity index | After prepn at 25°C | 24 h postincubation at 37°C | ||

| Conventional | 20.5 ± 0.9 | 215 ± 27 | 0.20 ± 0.07 | −26.6 ± 0.6 | −30.0 ± 1.0 |

| Pegylated | 30.6 ± 1.3 | 207 ± 17 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | −5.7 ± 0.4 | −5.6 ± 0.5 |

| Mixed (Lipo MA) | 229 ± 20 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | −11.1 ± 0.7 | −18.0 ± 1.0 | |

Values are means ± SD (n = 3).

Measurement performed in PBS at 25°C.

To investigate the possible transfer of PEG-DSPE from pegylated to conventional liposomes in the mixed formulation, we took advantage of the effect of pegylation on the zeta potential of the liposomes. The zeta potential values of the formulations remained unchanged over a 24-h period, when the formulations were kept at 25°C (data not shown), supporting the lack of transfer. On other hand, when the formulations were incubated at 37°C, a very slow increase of this parameter was observed from 0 to 6 h (−11 mV to −13 mV), but a significant change could only be established after 24 h (−18 mV) (Table 2). These data strongly suggest that the transfer of PEG lipid occurs slowly at 37°C but does not take place when the mixed formulation is kept at 25°C before the administration.

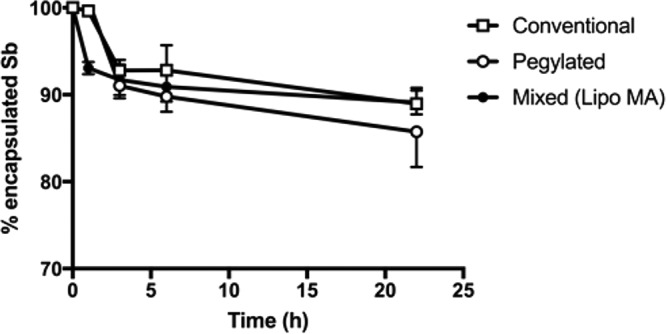

Another important question addressed here refers to the stability of the liposomal formulations regarding their ability to retain the encapsulated drug under conditions of temperature and osmotic pressure close to that of the serum. For this purpose, the three formulations were diluted 10-fold in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated at 37°C, and the amount of Sb release was determined in the external medium. As illustrated in Fig. 1, a significant release of the antimonial was evidenced from all the formulations with <30% of the release after 24 h. The kinetics was biphasic, with a first phase of fast drug release followed by a second phase of sustained release. The kinetics of Sb release from the mixed formulation was intermediate between those of conventional (slower) and pegylated (faster) liposomes. Nevertheless, no significant difference between the three formulations was observed. It is also noteworthy that the size distribution of liposome remained unchanged over the 24 h-incubation period (data not shown).

FIG 1.

In vitro stability of the different liposome formulations in PBS at 37°C. The graph shows the time course of change for the percentage of encapsulated Sb after 10-fold dilution of the formulations (conventional, pegylated, and mixed) in PBS and incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Data are shown as means ± the standard errors of the mean (SEM; n = 3).

The mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate controlled parasite replication and promoted reduction of the inflammatory process with the absence of granuloma formation in the liver.

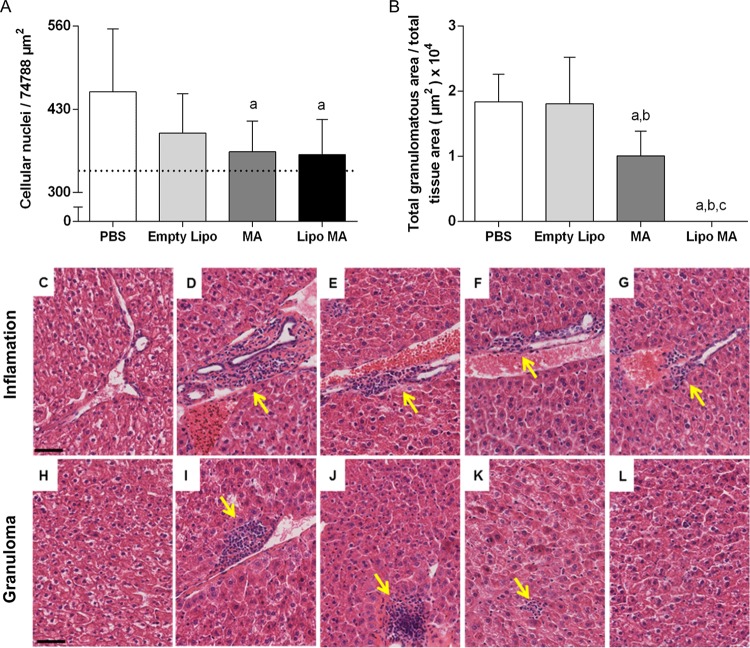

Histopathological analyses of the hepatic tissue demonstrated that infected animals treated with MA and a liposomal formulation of MA (Lipo MA) showed a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in the quantitative evaluation of inflammatory cells compared to the controls groups (uninfected and untreated) (Fig. 2A). When we evaluated the area of granulomas compared to the total area measured in the tissue (Fig. 2B) a significant decrease was observed (P < 0.05) in the MA and Lipo MA groups in relation to PBS and Empty Lipo animals. Furthermore, reductions in the size of granulomas were observed in the MA group. Finally, all of the animals treated with Lipo MA did not show granulomas.

FIG 2.

Histopathological alterations of livers in L. infantum-infected mice subjected to different treatment regimens (n = 12). (A) Morphometric analysis of the inflammatory process. Significant differences at P < 0.05 are indicated by the letter “a” for comparison with the infected and untreated (PBS) group (one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison posttest). (B) Total area of granuloma by the total area of the analyzed tissue. Significant differences at P < 0.05 are indicated by the letters “a,” “b,” and “c” for comparisons with the PBS, Empty Lipo, and MA groups, respectively (Kruskal-Wallis, followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison posttest). Data are shown as means ± the standard deviations (SD; n = 12). (C to L) Photomicrographs of the liver demonstrating histological aspects similar to the normality in uninfected and untreated group (C and H), moderate inflammatory process in the infected and untreated (PBS) group (D), and discrete inflammatory processes observed in the Empty Lipo group (E), the MA group (F), and the Lipo MA group (inflammatory processes are indicated by arrows) (G). Analysis of the granuloma area demonstrated that the infected and untreated (PBS) group (I) and the Empty Lipo group (J) presented a larger area of granulomas (arrow), and the animals of the MA group (K) presented smaller granulomas (arrow); in the Lipo MA (L) group no granulomas were observed. Hematoxylin-eosin staining was used. Bar, 50 μm. Magnification, 400×.

Figure 2C to L show the liver histological sections from BALB/c mice infected by L. infantum (MCAN/BR/2008/OP46) and subjected to different treatments. The livers of control animals—both uninfected and untreated—showed histological patterns consistent with a normal histological profile (Fig. 2C and H). Analysis of the inflammatory process showed that the PBS group animals exhibited moderate inflammatory granulomatous, a typical pattern, with exudate cells that were organized in the form of aggregates circumscribed by epithelioid cells and lymphocytes (Fig. 2D). Animals from groups treated with Empty Lipo, MA, and Lipo MA showed discrete inflammatory processes with focal accumulations of mononuclear cells (Fig. 2E to G).

The microscope analysis of granuloma area (Fig. 2I to L) demonstrated that the infected and untreated (PBS) group (Fig. 2I) and Empty Lipo group (Fig. 2J) presented a larger areas of granulomas corroborating with the quantitative analysis. In contrast, the animals in the MA group (Fig. 2K) presented smaller granulomas, and in the Lipo MA group (Fig. 2L) no granulomas were observed. Remarkably, treatment with Lipo MA reduces the inflammatory process and controls the replication of the parasite before granuloma formation and modification of the organ architecture.

L. infantum antigen (SLiAg) in vitro stimulation induces increase in IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells with decrease of IL-10 production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in mice treated with the mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate.

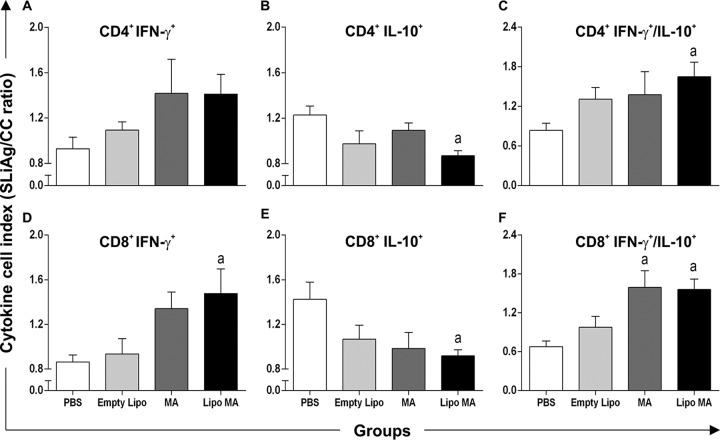

In order to evaluate the response of splenocytes after antigen-specific stimulation, cytokine profile in T cells subsets were evaluated trough the intracytoplasmic synthesis of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) (Fig. 3A). In CD4+ lymphocytes, we observed reduction in IL-10 production (P < 0.05) in Lipo MA animals compared with PBS group after treatment. On the other hand, CD4+ lymphocytes showed no alteration in IFN-γ production. When we evaluated the CD8+ lymphocytes, we observed higher numbers of CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells (P < 0.05) in the Lipo MA group compared to PBS-treated mice (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, we observed a decrease (P < 0.05) in IL-10 production by the CD8+ lymphocytes in the Lipo MA group compared to PBS-treated animals (Fig. 3E). We also evaluated the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio of the T-lymphocyte subsets, and this ratio was higher (P < 0.05) in the Lipo MA group than in the PBS group for both CD4+ and CD8+ splenocytes (Fig. 3C and F). Similarly, there was a consistently higher (P < 0.05) IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio only in the MA group in CD8+ splenocytes compared to PBS-treated animals (Fig. 3F).

FIG 3.

Intracytoplasmic cytokine indexes in splenocytes after in vitro stimulation with soluble L. infantum antigens (SLiAg). Profiles of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell producers of IFN-γ and IL-10 in the splenocytes of mice infected with L. infantum and subjected to different treatment regimens—i.e., the control group (PBS), the Empty Lipo group, the MA group, and the Lipo MA group—are shown. The y axis represents the ratio of cytokine production by respective cellular subpopulations from cultures stimulated with soluble L. infantum antigens (SLiAg) and control cultures (CC). The results are reported as cytokine indexes (i.e., the SLiAg/CC ratio) in CD4+ T cells (A, B, and C) and CD8+ T cells (D, E, and F) and are expressed as means of the cytokine indexes ± the SEM (n = 12). Significant differences at P < 0.05 are indicated by a letter “a” for comparison with the PBS group (one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison posttest).

Effectiveness of treatment using the mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate.

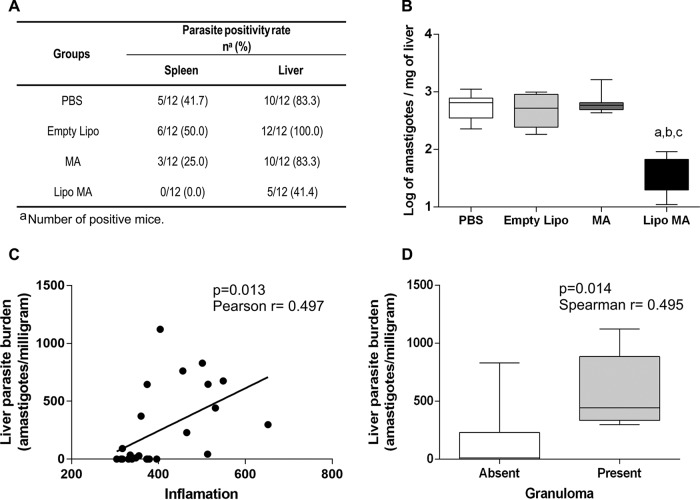

In order to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of the mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomal formulations with MA, the parasite burden in the spleens and livers of the different groups was evaluated 28 days after treatment (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4A, the PBS and Empty Lipo groups presented the highest percentages of parasite DNA in spleen: 41.7 and 50%, respectively. On the other hand, animals treated with meglumine antimoniate (MA) and the liposomal formulation (Lipo MA) demonstrated lower percentages of DNA parasites detected: 25 and 0%, respectively. Interestingly, only the Lipo MA group showed no detectable parasite DNA in the spleen at the endpoint of the treatment protocol. Furthermore, the evaluation of the positivity for DNA parasite in the liver showed that animals in the PBS and Empty Lipo groups were positive for the presence of L. infantum DNA at 83.3 and 100%, respectively. Moreover, the MA group showed a high percentage for L. infantum DNA with 83.3% of the animals with parasites in the liver, whereas only 41.4% of the Lipo MA animals demonstrated the presence of the parasite in this tissue (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Parasite burdens of spleens and livers from L. infantum-infected mice subjected to different treatment regimens (n = 12): control group (PBS), Empty Lipo group, MA group, and Lipo MA group. (A) DNA positivity (%) for L. infantum by qPCR in spleen and liver of all groups. (B) Quantification of the parasite burden in the liver. Results are expressed as the log amastigotes/mg of liver tissue. Box plots show the medians (horizontal lines across the box), interquartile ranges (vertical ends of the box), and whiskers (lines extending from the box to the highest and lowest values). Significant differences at P < 0.05 are indicated by letters “a,” “b,” and “c” for comparisons with the PBS, Empty Lipo, and MA treatment groups (Kruskal-Wallis, followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison posttest). (C) Correlation between liver parasite burden (amastigotes/mg) and inflammatory process in the PBS and Lipo MA treatment groups. (D) Box plots of the relationships between liver parasite burden versus granuloma in PBS and Lipo MA groups. The results are expressed on graphs as a scattering of individual values.

In addition to evaluating the percentage of positive animals in the liver, we also evaluated the parasite load trough qPCR results in different experimental groups (Fig. 4B). The Lipo MA group showed a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in parasite load in liver compared to the PBS, Empty Lipo, and MA groups. Moreover, we observed an intense reduction (14 times smaller) in the parasite load in the Lipo MA group compared to the PBS and Empty Lipo groups.

We also performed correlation analyses between the parasite load in the liver and the immunopathological changes (inflammatory process and granuloma) between the group treated with Lipo MA and the PBS group (Fig. 4C and D). Our data showed that the parasitic burden in the liver and the quantification of the inflammatory process were positively correlated between the Lipo MA and PBS groups (Pearson r = 0.497; P = 0.013) (Fig. 4C). We also detected a low positive correlation (Spearman r = 0.495; P = 0.014) when evaluating the hepatic parasite burden and granuloma formation (Fig. 4D). Thus, treatment using Lipo MA controlled splenic and liver parasitism, demonstrating its effectiveness for the experimental treatment of visceral leishmaniasis.

DISCUSSION

Many recent studies have addressed therapeutic approaches to the treatment of VL, but thus far there is no well-established and safe treatment for this critical disease. We concentrated our efforts here on elucidating the capacity of conventional and pegylated liposome carrying antimonial to promote parasite reduction; we also investigated the immunopathological response to infection by L. infantum.

In recent years, many experimental models have been developed and used for VL studies, each with specific characteristics; however, none of these studies accurately reproduces what happens in infected humans. The murine model is comparable to self-controlled oligosymptomatic cases and therefore is useful for the study of the protective immune response; this model has significantly contributed to the understanding of the hypothesis of immune-mediated mechanisms relevant to understand distinct aspects of leishmaniasis, as well as identified relevant elements associated with protective response in chemotherapeutic and immunoprophylactic approaches (11, 12). In addition, many studies have used the murine experimental model of VL and produced similar results of pathological, immunological, and parasitological evaluation using different strategies of treatments (immunotherapy and immunochemotherapy) (13–16). Thus, our VL model corroborates with other studies using BALB/c mice as an experimental model for treatment evaluation.

First, we sought to determine the kinetics and the spleen and liver commitment in BALB/c mice infected with L. infantum (strain MCAN/BR/2008/OP46) because this provides fundamental evidence for defining the moment of the therapeutic intervention and the endpoint of the experiment. Comparative analysis of qPCR in the spleen and liver demonstrated negativity in the spleen for up to 5 weeks and in 100% of positive animals in the liver up to 4 weeks postinfection. From week 6, the positivity for the DNA parasite remains constant in both organs, but with the higher percentages of positivity and parasitic load in the liver compared to the spleen. These results are in accordance with those of other authors who detected parasites in all spleen and liver samples at week 6 after infection (14, 17). Our results revealed that the initial commitment of the strain is to the liver, and over the course of the infection the parasite disseminates to the spleen, corroborating with the fact that the liver is the compartment of acute resolving infections, whereas the spleen is the compartment of parasite persistence (18).

For therapeutic intervention and animal necropsy, we chose days 14 and 28 postinfection, respectively, because positivity for the DNA parasite and parasite load in the liver were high until week 4 postinfection. In addition, the time points used for the therapeutic intervention and the end of the experiments corroborate with previous studies of chemotherapeutic evaluation using experimental murine models of VL (15, 19).

Prior to the administration of the different treatment regimens, characterization of conventional and pegylated liposomal formulations demonstrated high drug encapsulation efficiencies and precisely controlled vesicle size distributions. Both formulations showed mean vesicle diameters close to 200 nm and polydispersity indices of <0.3, characterizing the suspensions as monodispersed (20). The control of vesicle size is critical because of its influence on the pharmacokinetics and antileishmanial efficacy of liposome-encapsulated drugs (21, 22). Moreover, the diameter of pegylated liposomes should not exceed 200 nm in order to achieve long-circulating properties (23). Surprisingly, pegylated liposomes showed higher drug encapsulation efficiencies compared to conventional liposomes. A higher permeability of the pegylated membrane allowing faster balance of the drug between the internal and external aqueous compartments of liposomes may explain the difference observed.

The method used for the preparation of liposomes is based on the freeze-drying of negatively charged empty liposomes in the presence of cryoprotective sugar and the subsequent rehydration of the lyophilized liposomes with an aqueous solution of the antimonial drug, as previously described (21). Using this scheme, liposomes may be produced as preformed freeze-dried empty vesicles, and rehydration may be performed just before administration. This circumvents the stability problems arising from the long-term storage of liposomes in the presence of the water-soluble drug (4). The preparation process of liposomes developed here also shows significant improvements compared to previously used methods (10, 21). The calibration of liposome size before freeze-drying was performed by extrusion through 100-nm-pore-size polycarbonate membranes instead of ultrasonication. This innovative approach resulted in liposomes with a lower mean diameter and polydispersity index. Moreover, the final size calibration step used in the work of Azevedo et al. (10) could be omitted. Thus, the process developed in our study, owing to its simplicity, scalability, and reduced number of steps, appears to be more suitable than those previously described for the industrial production of these liposome formulations.

Although the method used to prepare liposomes differed from that described by Azevedo et al., the formulations are similar with respect to lipid compositions and exhibit close mean diameter values, which are factors that influence the pharmacokinetics of liposomes. On the other hand, considering the drug encapsulation efficiency of each type of liposome, the pegylated liposomes carry more Sb than conventional liposomes in our study, in contrast to the formulation of Azevedo et al. (10). Thus, although the specific biodistribution of each vesicle (conventional or pegylated) should be close for both formulations, the levels of antimony in the tissues may be different from those observed in the previous study (10).

The successful chemotherapy in BALB/c mice requires a robust cellular response associated with the development of parasite-specific cell-mediated immune response, including both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (24, 25). In the present study, we evaluated the intracytoplasmic cytokine expression in splenocytes of mice treated with a mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with MA under in vitro antigenic stimulation with SLiAg. We observed that treatment with Lipo MA induced increased production of type 1 cytokines (IFN-γ produced by CD8+ T cells) and a decrease in immunomodulatory cytokines (IL-10 produced by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells). Interestingly, animals from the MA and Lipo MA groups showed an increase in the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. It has been reported in experimental models of VL that CD8+ T cells are important for controlling L. infantum infection due to their ability to produce IFN-γ and/or their cytolytic activity (26). The immunomodulatory potential of antileishmanial drugs has been recognized by assessing its influence on macrophage-derived cytokines, mainly IFN-γ, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-10 (27). The increase in the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells observed in the antimoniate-treated groups is supported by the upregulation of the type 1 immune response, an effective strategy for parasite elimination. As a consequence of the treatment, pentavalent antimonials cause an increasing generation of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide, as previously demonstrated (28, 29). We believe that the increased levels of IFN-γ associated with low levels of IL-10 (an immunomodulatory cytokine) may be one of the factors responsible for the reduction of parasite burden in the Lipo MA group. Rolão et al. (17) analyzed the kinetics of cytokines in infection by L. infantum in a murine model and demonstrated that high IFN-γ values coincided with the reduction of the parasite load in the spleen, suggesting that this cytokine is responsible for the elimination of the parasites. In this scenario, our results demonstrate that chemotherapy with Lipo MA induces a type 1 immune response with low production of immunomodulatory cytokines, characterizing a control profile of the disease with the reduction of the parasite load.

After treatment with the mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate, the animals demonstrated a pronounced control of the parasite replication, promoting reduced inflammatory process and the absence of granuloma formation in the liver. In fact, histopathological analyses of the livers from infected animals treated with meglumine antimoniate revealed a prominent reduction in inflammatory infiltrate compared to the other groups of infected animals. These results are in agreement with another study using Glucantime in combination with ascorbic acid that observed no inflammation in the hepatic tissue (19). The control of hepatic infection in BALB/c model requires a coordinated immune response that involves the development of cellular infiltrates around infected macrophages known as inflammatory granulomas (30). Interestingly, we observed a reduction in the sizes of granulomas in the MA group, and the animals of the Lipo MA did not develop granulomas. These results were similar to those observed by Ferreira et al. (15), in which treatment with a liposome-encapsulated antimonial drug prevented the formation of granulomas and was able to protect the liver from the lesions caused by the infection. McElrath et al. (31) evaluated histopathological aspects in experimental visceral leishmaniasis and observed the first evidence of granuloma formation on day 8 after infection. Thus, we suggest the hypothesis that treatment with the mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate in the second week postinfection was able to reduce the number of parasites, as well as prevent the formation of granulomas. This hypothesis was reinforced by our results that demonstrated a positive correlation between the parasite load in the liver and the intensity of the inflammatory process.

In our study, we evaluated the efficacy of the treatment by the reduction of the parasite load in the spleen and liver after the chemotherapeutic strategies using qPCR. We believe that the low percentage of animals positive in the spleen observed in all groups is justified by kinetics of the infection of this strain, in which the initial commitment is to the liver and then it moves on to the spleen. As observed above, animals treated with Lipo MA showed the lowest percentage of L. infantum DNA detection in relation to the other groups in the spleen and liver. Azevedo et al. (10), using a mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate, evaluated the therapeutic efficacy using a different technique (limiting dilution) and also observed a decrease in the parasite load in the spleen compared to pegylated or conventional liposomal formulations (10). Here, animals treated with Lipo MA showed a significant reduction in parasite load in the liver compared to the other treatment groups, including the group treated with commercial MA. Surprisingly, the parasite load in the Lipo MA-treated group was about 14-fold lower than in the control groups (PBS and Empty Lipo). The higher efficacy of the mixed formulation may be attributed to its ability to promote more sustained blood levels of Sb5+, as suggested by the higher blood concentration of Sb5+ after 24 h, observed in the Azevedo study (10). Previous studies using conventional liposomes and pentavalent antimonials have also observed a suppression of the parasite load in target organs, such as the spleen, the liver, or bone marrow in murine models (15, 16, 32–34) and in dogs (35, 36), emphasizing the importance of liposomal formulations as conventional chemotherapy in treating leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that Lipo MA, composed of a mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate, is a promising antileishmanial formulation that induces a type 1 immune response, with decreased inflammation and less damage to hepatic tissue, associated with an important reduction in the parasite burden in the spleens and livers of treated mice. However, future studies are required in order to evaluate the use this mixture of conventional and pegylated liposomes with meglumine antimoniate combined with new therapeutic vaccines or substances with strong immunomodulatory effects as adjuvants (immunotherapy), which could lead to the next generation of drugs that will form new treatment strategies to cure visceral leishmaniases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

The L. infantum strain (MCAN/BR/2008/OP46) used in this study was first isolated from a symptomatic naturally infected dog provided by the Center of Zoonosis Control, Governador Valadares, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Restriction fragment length polymorphism-PCR analysis confirmed the species as L. infantum (unpublished data).The parasite growth was carried out as previously described by Moreira et al. (37).

Experimental animals and ethics statement.

We used isogenic BALB/c mice (female, 6 to 8 weeks old), which were maintained in the Centro de Ciência Animal da Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto (CCA/UFOP). The animals were maintained in appropriate plastic cages and fed standard rodent food pellet and water ad libitum. The adopted procedures in this study were in accordance with National Council on Animal Experiments and Control (CONCEA, Brazil) guidelines and approved by the Comitê de Ética no Uso de Animais da UFOP (CEUA/UFOP) under protocol 10/2014.

Analysis of the dynamics of infection.

To evaluate the parasite dynamics of the MCAN/BR/2008/OP46 strain, female BALB/c mice, aged 6 to 8 weeks (n = 5, per experimental group), were each inoculated with 107 promastigotes of the parasite by intravenous (i.v.) administration through the tail vein. The animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation in the interval from weeks 2 to 8 postinfection. At the time of dislocation, fragments of spleen and liver were collected and stored at −80°C in a freezer for subsequent molecular analysis.

Treatment regimens.

Infected BALB/c mice were divided into four groups (n = 12, per experimental group), which received one of the following the treatment regimens, as a single i.v. bolus injection through the tail vein: (i) PBS only; (ii) Empty Lipo; (iii) free MA, 20 mg/kg of body weight; or (iv) a liposomal formulation of meglumine antimoniate consisting of mixed conventional and pegylated liposomes at 1:1 lipid mass ratio (Lipo MA), 20 mg/kg of body weight. Mixing of conventional and pegylated liposome suspensions containing meglumine antimoniate to prepare the combined Lipo MA formulation was performed just before administration to the respective group of animals. The treatment regimens were administered to the animals at 14 days postinfection (dpi) with L. infantum. Euthanasia of the animals was performed at 28 dpi.

Chemicals.

Cholesterol (CHOL; purity, ≥99%) and dicetylphosphate (DCP; purity, ≥98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Distearoylphosphatidylcholine (DSPC) and distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine-polyethylene glycol 2000 (DSPE-PEG) were obtained from Lipoid (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) was purchased from Sanofi-Aventis Farmacêutica, Ltda., São Paulo, Brazil.

Preparation and characterization of the liposomal formulation.

Two different liposomal suspensions containing meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) were prepared: one consisting of conventional liposomes made from DSPC, CHOL, and DCP at molar ratio of 5:4:1 and the other consisting of pegylated liposomes made from DSPC, CHOL, DCP, and DSPE-PEG at molar ratio of 4.7:4:1:0.47.

The encapsulation of Glucantime in liposomes was performed as described previously (4, 10) with the following modifications. Briefly, multilamellar liposomes were prepared in deionized water at the final lipid concentration of 55 g/liter. These multilamellar liposomes were transformed into unilamellar vesicles through five freeze-thaw cycles, followed by repeated extrusions (10 times) across 100-nm-pore-size polycarbonate membranes (38). The resulting liposome suspensions were mixed with an aqueous sucrose solution at a 3:1 sugar/lipid mass ratio. The mixtures were then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently freeze-dried for 48 h (freeze-dryer L101; Liotop, São Carlos/SP, Brazil). Rehydration of the dried powder was performed with a solution of Glucantime diluted in water (Sb concentration of 40 g/liter) as follows. A total of 100% of the original liposome volume of Glucantime solution was added to the lyophilized powder, and the mixture was vortexed and incubated for 45 min at 65°C. The liposome suspensions were then diluted 1:6 with PBS (0.15 mol/liter NaCl, phosphate [0.01 mol/liter], pH 7.2) and subjected to centrifugation (23,000 × g, 40 min, 15°C). The liposome pellet was finally resuspended in NaCl at 0.15 mol/liter at a final lipid concentration of 67 g/liter. Empty (drug-free) liposomes were also prepared using the same protocol, but replacing the Glucantime solution with NaCl at 0.15 mol/liter.

The mean hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index and the zeta potential of the vesicles in suspension were determined by photon correlation spectroscopy at 25°C using a particle size analyzer (Zetasizer S90; Malvern, United Kingdom). The amount of Sb was determined in the resulting liposome suspension, after digestion of the sample with nitric acid, by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry (Analyst AA600; Perkin-Elmer, Inc., Waltham, MA).

The suspensions of conventional and pegylated liposomes and their 1:1 (vol/vol) mixtures were evaluated for the stability of the vesicle size and zeta potential and the drug encapsulation after dilution at 1:10 in PBS and incubation at 37°C. After different incubation periods, an aliquot was centrifuged (22,000 × g, 60 min, 4°C), the supernatant was recovered, and the Sb level was determined by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry.

Histopathology and morphometric analysis.

For histopathological analysis, fragments of liver tissue were fixed in methanol and dimethyl sulfoxide (4:1, vol/vol) for at least 72 h and routinely processed and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm thick) were mounted on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin-eosin for standard histological procedures. For morphometric analyses of the granulomas present in the liver sections, we determined the ratio obtained by dividing the total granulomatous area by the total tissue area (n = 12 per experimental group). The total average area of granulomas/animal was divided by the total tissue area assessed in the objective of 10× (12.957.354 μm2). All images were digitalized by a Leica DFC340FX microcamera associated with Leica DM5000B microscopy, followed by analysis using Leica Qwin V3 software.

Morphometric studies of inflammation involved analyzing images of 10 randomly selected fields (total area, 74.788 μm2) on a single slide per animal. Hepatic inflammatory infiltration was quantified by counting the cell nuclei present in the different sections of the liver and establishing the difference between the number of cell nuclei present in the infected animals with that observed in noninfected ones, thus determining the number of inflammatory cells. All images were obtained with a 40× objective lens.

Intracellular cytokine analysis in spleen.

After euthanasia, the spleens of the animals (n = 12 per experimental group) were removed, and cell suspensions were prepared as described by Taylor et al. (39). The protocol used for dosing intracytoplasmic cytokines in spleen was previously described by Vieira et al. (40), with some modifications.

The organ was immersed in cold RPMI 1640 (10 ml) in a petri dish and placed on ice for maceration. Fragments were squashed using a blunt glass rod and filtered through stainless-steel gauze to obtain a single-cell suspension. The suspension was washed twice in RPMI 1640 and resuspended at 107 cells/ml. Two 15-ml polypropylene tubes (Falcon; Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) were prepared: (i) a control tube (2.0 ml of RPMI and 2.0 ml of cell suspension) and (ii) a tube stimulated with L. infantum antigens at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml. Suspensions of spleen cells were incubated for 12 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 in air humidified incubator, followed by incubation with brefeldin A (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 40 mg/ml for an additional 4 h.

At the end of the incubation period, cultures previously treated with 2 mM EDTA (Sigma) were washed once with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer prepared as PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide (Sigma) and centrifuged at 450 × g for 7 min at 18°C. After resuspension in 2 ml of FACS buffer, the culture was immunostained with the fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled monoclonal antibody anti-CD4 or CD8 (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. After the lysing/fixation procedure, membrane-stained leukocytes were permeabilized with FACS perm-buffer (FACS buffer with 0.5% saponin), followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature in the dark in the presence of 20 μl of phycoerythrin-labeled anti-cytokine monoclonal antibodies (IFN-γ and IL-10) from Serotec and Caltag, respectively. After intracytoplasmic cytokine staining, the cells were washed and fixed in FACS FIX solution for storage at 4°C prior to flow cytometric acquisition and analysis. Data collection was performed using a flow cytometer FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, USA). FlowJo software was used for data analysis (Tree Star, USA). The intracytoplasmic cytokines yield splenocytes that were expressed in the index form of a stimulated culture with a L. infantum antigens/control culture (SLiAg/CC) ratio obtained by dividing the intracytoplasmic cytokine production percentage produced by the respective populations.

Parasite load.

The parasite load was detected by quantitative real-time PCR methods. After the animals were euthanized, the total genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 15 to 30 mg of tissue (spleen and liver) using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The concentration of DNA obtained from the tissues was determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer 2000 (Thermo Scientific), and the quality of the samples was measured by a 260 nm/280 nm ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. The DNA samples were frozen at −20°C until further analyses.

A standard curve was composed with L. infantum DNA (MCAN/BR/2008/OP46 strain) extracted from 108 promastigotes/ml using the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method as previously described by Moreira et al. (37). After elution, the DNA pellet was extracted in 100 ml of autoclaved ultrapure water, and the concentration was 106 parasites/ml. From there, serially dilutions were made from 10x, obtaining seven points on the curve 106-1 parasites.

The reactions were performed using TaqMan Gene Expression master mix (Applied Biosystems, USA), DNA (100 ng), primers (1 μM), 0.25 μM TaqMan probe (VIC 5′-AGG AAA CCT GTG GAG CC-3′ MGB NFQ), and nuclease-free water in sufficient quantity for a final volume of 10 μl per well. The selected primer pair (forward, 5′-AGC GCC TCA CCA CGA TTG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGC GGG CAC CGA AGA GA-3′; GenBank accession number AF009147) amplified a 90-bp fragment of a single-copy of the DNA polymerase gene of L. infantum. In order to verify the integrity of the samples, primers were used for murine TNF-α (5′-TCCCTCTCATCAGTTCTATGGCCCA-3′; 5′-CAGCAAGCATCTATGCACTTAGACCCC-3′) to amplify a 170-bp product (41). The PCR conditions were as follows: one incubation step at 50°C for 2 min and an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing-extension at 60°C for 1 min. All samples were run on MicroAmp optical 96-well reaction plates (Applied Biosystems) sealed with MicroAmp optical adhesive film (Applied Biosystems). Each 96-well reaction plate contained a standard curve in triplicate (efficiency, 96.0%; r2 = 0.99) in duplicate samples, a negative control (no DNA), and control genes.

Reactions were processed and analyzed in an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The results were expressed qualitatively as the percentage of positivity and quantitatively as the number of amastigotes/mg of tissue multiplied by the total weight of the organ (spleen and liver).

Statistical analyses.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (Prism Software, Irvine, CA). Each set of results was first checked for normal distribution using Kolmogorov-Smirnov, D'Agostinho and Pearson, and Shapiro-Walk tests. Normally distributed data were analyzed through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's post hoc test. For non-normally distributed data, a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison test were used. In all cases, differences with P < 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS v20 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Regarding the PBS and Lipo MA groups, Pearson and Spearman rank correlation was computed to investigate associations between liver parasite burden versus inflammatory process and liver parasite burden versus granuloma, respectively. Statistical significance was determined when P < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maria Chaves dos Santos for technical support and Narjara Alcântara Sacramento for scientific contributions. We are also grateful to the Centro de Ciência Animal-CCA/UFOP.

We acknowledge the Brazilian agencies CNPq (grant 476951/2013-5), FAPEMIG (grants APQ-01358-12, APQ-01008-14, and PRONEX APQ-01373-14), CAPES, UFMG (Programa Institucional de Auxílio à Pesquisa de Docentes Recém-Contratados: PRPq 01/2017), and UFOP for financial support. L.E.S.R., A.B.R., C.M.C., F.J.G.F., R.C.F.D.B., F.A.S.M., and J.M.D.O.C are grateful for scholarships from FAPEMIG, CAPES, and CNPq. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den Boer M. 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 7:e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roatt BM, Aguiar-Soares RDDO, Coura-Vital W, Ker HG, Moreira NDD, Vitoriano-Souza J, Giunchetti RC, Carneiro CM, Reis AB. 2014. Immunotherapy and immunochemotherapy in visceral leishmaniasis: promising treatments for this neglected disease. Front Immunol 5:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frézard F, Demicheli C, Ribeiro RR. 2009. Pentavalent antimonials: new perspectives for old drugs. Molecules 14:2317–2336. doi: 10.3390/molecules14072317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frézard F, Demicheli C. 2010. New delivery strategies for the old pentavalent antimonial drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 7:1343–1358. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2010.529897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridley RG, Fairlamb AH, Vial HJ. 2003. Drugs against parasitic diseases: R&D methodologies and issues. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamboni WC. 2008. Concept and clinical evaluation of carrier-mediated anticancer agents. Oncologist 13:248–260. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen TM, Cullis PR. 2013. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 65:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemann C, Yau-Young A. 1991. Liposomes containing synthetic lipid derivatives of poly(ethylene glycol) show prolonged circulation half-lives in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1066:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drummond DC, Meyer O, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, Papahadjopoulos D. 1999. Optimizing liposomes for delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to solid tumors. Pharmacol Rev 51:691–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azevedo EG, Ribeiro RR, da Silva SM, Ferreira CS, de Souza LE, Ferreira AA, de Oliveira E Castro RA, Demicheli C, Rezende SA, Frézard F. 2014. Mixed formulation of conventional and pegylated liposomes as a novel drug delivery strategy for improved treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 11:1551–1560. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.932347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg R, Dube A. 2006. Animal models for vaccine studies for visceral leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res 123:439–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Mendonça LZ, Resende LA, Lanna MF, Aguiar-Soares RD, et al. 2016. Multicomponent LBSap vaccine displays immunological and parasitological profiles similar to those of Leish-Tec® and Leishmune® vaccines against visceral leishmaniasis. Parasit Vectors 9:472. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1752-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray HW. 2005. Interleukin 10 receptor blockade: pentavalent antimony treatment in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Acta Trop 93:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castro RA, Silva-Barcellos NM, Licio CS, Souza-Testasicca MC, Ferreira FM, Batista MA, Silveira-Lemos D, Moura SL, Frézard F, Rezende SA. 2014. Association of liposome-encapsulated trivalent antimonial with ascorbic acid: an effective and safe strategy in the treatment of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS One 9:e104055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira FM, Castro RAO, Batista MA, Rossi FMO, Silveira-Lemos D, Frézard F, Moura SAL, Rezende SA. 2014. Association of water extract of green propolis and liposomal meglumine antimoniate in the treatment of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Parasitol Res 113:533–543. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3685-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi J, Malla N, Kaur S. 2014. A comparative evaluation of efficacy of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and immunochemotherapy in visceral leishmaniasis-an experimental study. Parasitol Int 63:612–620. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolão N, Cortes S, Gomes-Pereira S, Campino L. 2007. Leishmania infantum: mixed T-helper-1/T-helper-2 immune response in experimentally infected BALB/c mice. Exp Parasitol 115:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodrigues A, Claro M, Alexandre-Pires G, Santos-Mateus D, Martins CM, Valério-Bolas A, Rafael-Fernandes M, Pereira MA, Pereira da Fonseca I, Tomás AM, Santo-Gomes G. 2016. Leishmania infantum antigens modulate memory cell subsets of liver resident T lymphocyte. Immunobiology 222:409–422. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato KC, Morais-Teixeira E, Reis PG, Silva-Barcellos NM, Salaun P, Campos PP, Dias Correa-Junior J, Rabello A, Demicheli C, Frezard F. 2013. Hepatotoxicity of pentavalent antimonial drug: possible role of residual sb(iii) and protective effect of ascorbic acid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:481–488. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01499-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter DG, Frisken BJ. 1998. Effect of extrusion pressure and lipid properties on the size and polydispersity of lipid vesicles. Biophys J 74:2996–3002. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)78006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schettini DA, Ribeiro RR, Demicheli C, Rocha OGF, Melo MN, Michalick MSM, Frézard F. 2006. Improved targeting of antimony to the bone marrow of dogs using liposomes of reduced size. Int J Pharm 315:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson DS, Endsley AN, Huang L. 2012. Design considerations for liposomal vaccines: influence of formulation parameters on antibody and cell-mediated immune responses to liposome associated antigens. Vaccine 30:2256–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodle MC, Lasic DD. 1992. Sterically stabilized liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1113:171–199. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90038-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrión J, Nieto A, Iborra S, Iniesta V, Soto M, Folgueira C, Abanades DR, Requena JM, Alonso C. 2006. Immunohistological features of visceral leishmaniasis in BALB/c mice. Parasite Immunol 28:173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islamuddin M, Chouhan G, Farooque A, Dwarakanath BS, Sahal D, Afrin F. 2015. Th1-biased immunomodulation and therapeutic potential of Artemisia annua in murine visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e3321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polley R, Stager S, Prickett S, Maroof A, Zubairi S, Smith DF, Kaye PM. 2006. Adoptive immunotherapy against experimental visceral leishmaniasis with CD8+ T cells requires the presence of cognate antigen. Infect Immun 74:773–776. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.773-776.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha P, Mukhopadhyay D, Chatterjee M. 2011. Immunomodulation by chemotherapeutic agents against leishmaniasis. Int Immunopharmacol 11:1668–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basu JM, Mookerjee A, Sen P, Bhaumik S, Sen P, Banerjee S, Naskar K, Choudhuri SK, Saha B, Raha S, Roy S. 2006. Sodium antimony gluconate induces generation of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide via phosphoinositide 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in Leishmania donovani-infected macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1788–1797. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1788-1797.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muniz-Junqueira MI, de Paula-Coelho VN. 2008. Meglumine antimoniate directly increases phagocytosis, superoxide anion and TNF-α production, but only via TNF-α it indirectly increases nitric oxide production by phagocytes of healthy individuals, in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol 8:1633–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray HW, Granger AM, Mohanty SK. 1991. Response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis: T cell-dependent but interferon-gamma- and interleukin-2-independent. J Infect Dis 163:622–624. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McElrath MJ, Murray HW, Cohn ZA. 1988. The dynamics of granuloma formation in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Exp Med 167:1927–1937. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.6.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mullen AB, Baillie AJ, Carter KC. 1998. Visceral leishmaniasis in the BALB/c mouse: a comparison of the efficacy of a nonionic surfactant formulation of sodium stibogluconate with those of three proprietary formulations of amphotericin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2722–2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins M, Baillie AJ, Carter KC. 1992. Visceral leishmaniasis in the BALB/c mouse: sodium stibogluconate treatment during acute and chronic stages of infection. II. Changes in tissue drug distribution. Int J Pharm 83:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalat SA, Khamesipour A, Bavarsad N, Fallah M, Khashayarmanesh Z, Feizi E, Neghabi K, Abbasi A, Jaafari MR. 2014. Use of topical liposomes containing meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) for the treatment of L. major lesion in BALB/c mice. Exp Parasitol 143:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Da Silva SM, Amorim IFG, Ribeiro RR, Azevedo EG, Demicheli C, Melo MN, Tafuri WL, Gontijo NF, Michalick MSM, Frézard F. 2012. Efficacy of combined therapy with liposome-encapsulated meglumine antimoniate and allopurinol in treatment of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2858–2867. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00208-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribeiro RR, Moura EP, Pimentel VM, Sampaio WM, Silva SM, Schettini DA, Alves CF, Melo FA, Tafuri WL, Demicheli C, Melo MN, Frézard F, Michalick MSM. 2008. Reduced tissue parasitic load and infectivity to sand flies in dogs naturally infected by Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi following treatment with a liposome formulation of meglumine antimoniate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2564–2572. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00223-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreira NDD, Vitoriano-Souza J, Roatt BM, Vieira PMDA, Ker HG, de Oliveira Cardoso JM, Giunchetti RC, Carneiro CM, de Lana M, Reis AB. 2012. Parasite burden in hamsters infected with two different strains of leishmania (Leishmania) infantum: “Leishman Donovan units” versus real-time PCR. PLoS One 7:e47907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nayar R, Hope MJ, Cullis PR. 1989. Generation of large unilamellar vesicles from long-chain saturated phosphatidylcholines by extrusion technique. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 986:200–206. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90468-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor AP, Murray HW. 1997. Intracellular antimicrobial activity in the absence of interferon-gamma: effect of interleukin-12 in experimental visceral leishmaniasis in interferon-gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med 185:1231–1239. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vieira PMDA, Francisco AF, Machado EMDM, Nogueira NC, Fonseca KDS, Reis AB, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Martins-Filho OA, Tafuri WL, Carneiro CM. 2012. Different infective forms trigger distinct immune response in experimental Chagas disease. PLoS One 7:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cummings KL, Tarleton RL. 2003. Rapid quantitation of Trypanosoma cruzi in host tissue by real-time PCR. Mol Biochem Parasitol 129:53–59. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(03)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]